Published online Aug 21, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i31.10953

Revised: March 15, 2014

Accepted: May 23, 2014

Published online: August 21, 2014

Processing time: 283 Days and 22.3 Hours

AIM: To compare the recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) of hepatitis B virus (HBV)-positive hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) after living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) and deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT).

METHODS: We retrospectively collected clinical data from 408 liver cancer patients from February 1999 to September 2012. We used the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test to analyze the characteristics of LDLT and DDLT. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to compare the RFS and OS in HCC.

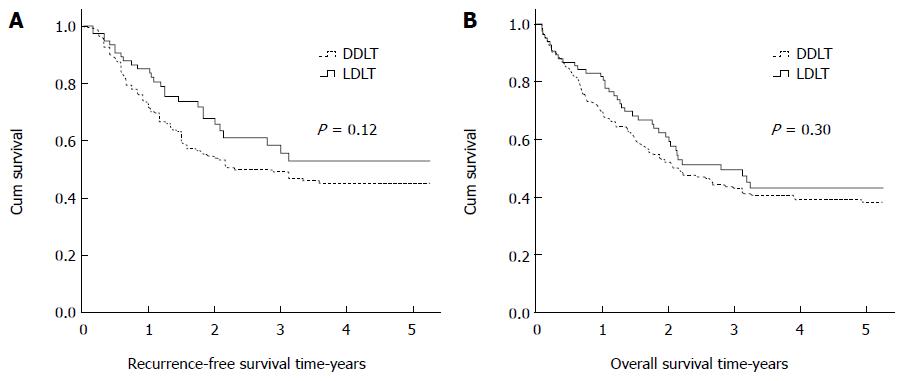

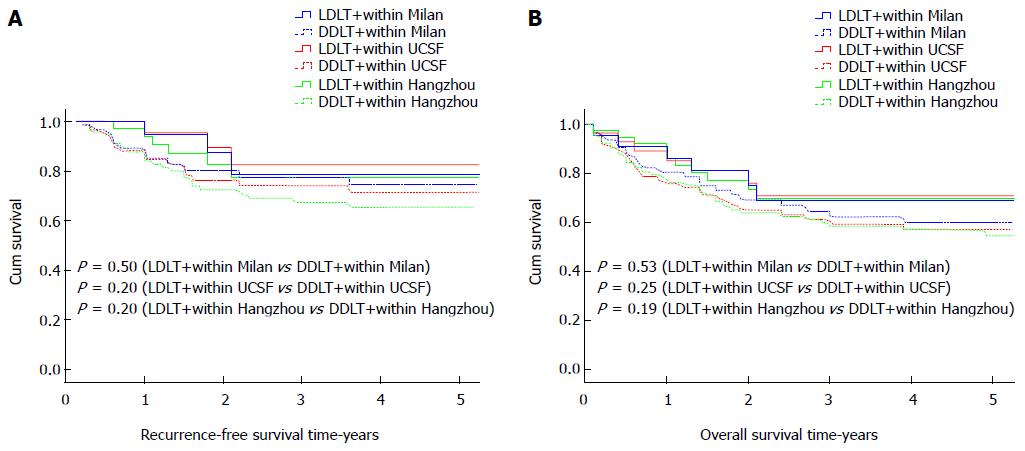

RESULTS: Three hundred sixty HBV-positive patients (276 DDLT and 84 LDLT) were included in this study. The mean follow-up time was 27.1 mo (range 1.1-130.8 mo). One hundred eighty-five (51.2%) patients died during follow-up. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year RFS rates for LDLT were 85.2%, 55.7%, and 52.9%, respectively; for DDLT, the RFS rates were 73.2%, 49.1%, and 45.3% (P = 0.115). The OS rates were similar between the LDLT and DDLT recipients, with 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates of 81.8%, 49.5%, and 43.0% vs 69.5%, 43.0%, and 38.3%, respectively (P = 0.30). The outcomes of HCC according to the Milan criteria after LDLT and DDLT were not significantly different (for LDLT: 1-, 3-, and 5-year RFS: 94.7%, 78.7%, and 78.7% vs 89.2%, 77.5%, and 74.5%, P = 0.50; for DDLT: 86.1%, 68.8%, and 68.8% vs 80.5%, 62.2%, and 59.8% P = 0.53).

CONCLUSION: The outcomes of LDLT for HCC are not worse compared to the outcomes of DDLT. LDLT does not increase tumor recurrence of HCC compared to DDLT.

Core tip: Whether there is a higher tumor recurrence for living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) than for deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT) for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has recently become a subject of debate. Our results suggest that LDLT does not increase the tumor recurrence of HCC compared to DDLT. The recurrence-free survival and long-term survival times of LDLT for HCC are higher than those of DDLT.

- Citation: Xiao GQ, Song JL, Shen S, Yang JY, Yan LN. Living donor liver transplantation does not increase tumor recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma compared to deceased donor transplantation. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(31): 10953-10959

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i31/10953.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i31.10953

Liver transplantation (LT) is an ideal treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) because it can completely clear a tumor in the liver and improve the patient’s liver function. Many studies have demonstrated that the outcomes of HCC patients according to the Milan criteria (single tumor ≤ 5 cm in size or ≤ 3 tumors each ≤ 3 cm in size, and no macrovascular invasion) or the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) criteria (single tumor ≤ 6.5 cm, or 3 or fewer nodules with the largest lesion ≤ 4.5 cm and a total tumor diameter ≤ 8 cm, without vascular invasion) are positive[1-5]. Most researchers suggest that the long-term outcomes of LT are better than those of hepatectomy for HCC with Milan or UCSF criteria[2,4]. Nonetheless, LT is greatly limited by the shortage of available livers. Many HCC patients on waiting lists have died before a live graft could become available. The idea of using living donor liver grafts for orthotopic LT started in 1966 and 1969[6,7]. It took more than 20 years for the idea to materialize in clinical practice[8].

Living donor living transplantation (LDLT) is considered an alternative to deceased donor living transplantation (DDLT). Many researchers have suggested that the recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) rates of patients are similar for LDLT and DDLT[9-17]. However, some investigators have indicated that the RFS and OS rates of LDLT are worse compared to the rates after DDLT[18-23]. In this study, we aim to compare the prognoses of HCC patients after LDLT and DDLT at our transplantation center, followed by a comparison of the outcomes of HCC after LDLT and DDLT according to the Milan, UCSF, and Hangzhou criteria.

We obtained the patient data from the China Liver Transplant Registry (CLTR) database. The demographic and clinical data of 408 liver cancer patients who underwent LT at our center from February 1999 to September 2012 was retrospectively collected, with preoperative demographic, clinical, and laboratory data for all patients being recorded. Systemic imaging was employed within 1 week before surgery. The pathological data for the explanted livers were considered the gold standard for tumor assessment. Vascular invasion and tumor differentiation were also assessed by pathology. Patients who were not hepatitis B virus (HBV)-positive, were not diagnosed with HCC by pathology, were younger than 18 years-old, or had died within 1 mo after transplantation were excluded from this study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the West China Hospital of Sichuan University in Sichuan Province. We obtained informed written consent from all patients according to the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association.

A modified technique for adult-to-adult LDLT was used at our LT center[24]. We used the surgical technique of the anterior approach for liver resection for recipients. First, we dissected the first porta area and disconnected the left and right branches of the hepatic artery, biliary duct, and portal vein. Second, we blocked the retrohepatic inferior vena cava and suprahepatic vena cava and then removed the recipient liver. The anterior approach provides a “no-touch” technique in resecting the liver tumor, decreasing the chance of tumor rupture and metastasis. After liver resection, 5-fluorouracil solution was used to lavage the peritoneal cavity.

The retro-hepatic portion of the inferior vena cava was removed along with the liver, and the piggyback technique (the recipient’s inferior vena cava being preserved) was employed for LDLT patients. In the early stages for DDLT, the standard technique without the use of a venovenous bypass was used at our center. The piggyback technique was implemented for most of the DDLT patients.

After surgery, the patients received immunosuppressive drugs, including corticosteroids, cyclosporine, or tacrolimus with or without mycophenolate mofetil. The blood dosages of cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil were maintained at low levels. In general, corticosteroids were withdrawn after 3 mo of treatment. HBV immunoglobulins or antivirus drugs, such as lamivudine, adefovir, telbivudine, and entecavir, were administered in HBV-positive LT patients after operation[25].

After transplantation, the patients were followed-up with outpatient visits or by telephone, and every year we invited the patients who had received LT to visit our center. The recipients received routine blood examinations, α-fetoprotein (AFP) tests, and chest X-ray examinations every month in the first year. In the first half of the second year, the patients received these examinations once every 2 mo. In the following years, the patients underwent these examinations every 3-6 mo, or when necessary. When necessary, we took abdominal computed tomography (CT), abdominal magnetic resonance imaging, chest CT, head CT, and bone scans of the patients. Any suspicious lesions in the liver or lungs of the recipients were biopsied, if deemed necessary. Brain and bone pain, as well as progressive growth of bone, were recorded. The date of tumor recurrence was considered as the time that the AFP level began to rise after tumor recurrence had been confirmed. If patients had tumor recurrence, we recorded the time and administered the appropriate treatment. If the patient died, we recorded the time and cause of death.

We used SPSS v17.0 to analyze the data. The independent sample t-test, Pearson’s χ2 test, and Fisher’s exact test were used to analyze the differences in the demographic and clinical data from patients after LDLT and DDLT. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to analyze the RFS and OS rates of the HCC patients. The statistical data were expressed as mean ± SD. The confidence interval quoted area was 95%; statistically significant differences were defined as P < 0.05.

The data for patients who underwent LT came from the CLTR database. The patients were regularly followed up to December 2012. Of all 408 liver cancer patients who received LT at our medical center from February 1999 to September 2012, 48 patients were excluded from this study; eighteen were not HCC patients, eighteen patients died within 1 month after transplantation, ten were not HBV-positive, and two patients were younger than 18 years-old. This left 360 patients to be included from this study. Of the included patients, 84 (23.3%) received LDLT, and 276 (76.7%) received DDLT. Among the 360 patients, there were 35 (9.7%) women and 325 (90.3%) men. The mean age of the HCC patients who received LT was 46.6 ± 9.86 years. The mean follow-up time of all patients was 2.22 years (range: 1.1-10.7 years).

The demographic and clinical data of all LDLT and DDLT patients are shown in Table 1. There was a statistically significant difference in the preoperative adjuvant therapy. There were no significant differences in terms of recipient gender; age; body mass index; Child-Pugh score; Meld score; AFP level; tumor number; largest tumor size; total tumor size; vascular invasion; adherence to the Milan, UCSF, or Hangzhou criteria; HBV-DNA level; or tumor differentiation (Table 1).

| Variables | LDLT | DDLT | P value |

| (n = 84) | (n = 276) | (2-tailed) | |

| Gender (F/M) | 6/78 | 29/247 | 0.36 |

| Age-yr (mean) | 44.3 | 47.3 | 0.06 |

| Age, yr (< 60/≥ 60) | 79/5 | 238/38 | 0.05 |

| BMI (< 24/24-27/≥ 27) | 57/19/8 | 185/65/26 | 0.98 |

| Child-Pugh (A/B/C) | 43/34/7 | 137/119/20 | 0.89 |

| Meld score ( ≤ 10/10-20/> 21) | 47/33/2 | 150/92/19 | 0.25 |

| AFP (μg/L) (< 400/≥ 400) | 37/43 | 141/135 | 0.45 |

| Preoperative | 17/67 | 101/175 | 0.0051 |

| adjuvant therapy (Y/N) | |||

| Tumor No. ( ≤ 3/> 3) | 62/18 | 206/50 | 0.56 |

| Largest Tumor Size | 40/24/16 | 128/65/73 | 0.35 |

| ( ≤ 5/5-9/> 9)-cm | |||

| Total tumor size | 28/21/31 | 77/41/91 | 0.46 |

| ( ≤ 5/5-9/> 9)-cm | |||

| Vascular invasion (Y/N) | 20/64 | 97/179 | 0.05 |

| Milan criteria (Y/N) | 22/58 | 69/199 | 0.75 |

| UCSF criteria (Y/N) | 28/52 | 84/184 | 0.54 |

| Hangzhou criteria (Y/N) | 39/41 | 112/145 | 0.42 |

| HBV-DNA-copies/ml | 32/52 | 76/131 | 0.83 |

| (< 1.00E + 03/> 1.00E + 03) | |||

| Differentiation (1-2/3-4) | 32/11 | 114/70 | 0.13 |

According to our analysis, the percentage of HCC patients who received the preoperative adjuvant therapy was higher in patients after DDLT than LDLT. Of the 118 patients who received preoperative adjuvant therapy, 83 (70.3%) received transcatheter arterial chemoembolization therapy only, 18 (15.3%) patients radiofrequency ablation treatment only, 11 (9.3%) underwent hepatectomy only, and 6 (5.1%) patients received more than two treatment methods. The analysis suggested that preoperative adjuvant therapy had no impact on the RFS and OS between DDLT and LDLT.

Of all 360 patients included in this study, the median wait times for LDLT and DDLT were 0.9 and 1.6 mo, respectively. A total of 138 (38.3%) patients had tumor recurrence, and 198 (55.0%) patients died during follow-up. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year RFS rates of the patients in our study were 76.2%, 50.9%, and 47.2%, respectively, while the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates were 72.5%, 4.5%, and 40.0%, respectively. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year RFS rates were 85.2%, 55.7%, and 52.9% for LDLT vs 73.2%, 49.1%, and 45.3% for DDLT (P = 0.12). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates were 81.8%, 49.5%, and 43.0% for LDLT vs 69.1%, 43.0%, and 38.3% for DDLT (P = 0.30). There were no significant differences in the RFS and OS rates between LDLT and DDLT (Figure 1).

We divided all HCC patients who underwent LDLT and DDLT according to the Milan, UCSF, and Hangzhou criteria into 6 categories. We then compared the RFS and OS rates of these categories. The outcomes are shown in Figure 2. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year RFS rates according to the Milan criteria were 94.7%, 78.7%, and 78.7% for LDLT vs 89.2%, 77.5%, and 74.5% for DDLT (P = 0.50). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year RFS rates according to the UCSF criteria were 95.5%, 82.6%, and 82.6% for LDLT vs 88.0%, 74.0%, and 71.4% for DDLT (P = 0.20). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year RFS rates according to the Hangzhou criteria were 94.0%, 77.3%, and 77.3% for LDLT vs 87.9%, 67.3%, and 65.3% for DDLT (P = 0.20). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates according to the Milan criteria were 86.1%, 68.8%, and 68.8% after LDLT vs 80.5%, 62.2%, and 59.8% after DDLT (P = 0.53). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates according to the UCSF criteria were 85.1%, 70.9%, and 70.9% for LDLT vs 75.8%, 59.2%, and 57.1% for DDLT (P = 0.25). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates according to the Hangzhou criteria were 86.3%, 69.6%, and 69.6% after LDLT vs 76.2%, 58.3%, and 56.6% after DDLT (P = 0.19). There were no significant differences in the RFS and OS rates between LDLT and DDLT patients divided according to the Milan, UCSF, and Hangzhou criteria (Figure 2).

Compared with DDLT, LDLT can shorten the pre-transplant waiting time and can also solve the issue of limited donors. LDLT is widely accepted as a treatment for patients with end-stage liver disease. At the same time, LT is the best choice for HCC because it can completely clear a tumor in the liver and solve the problem of liver cirrhosis. However, LT is greatly limited by the shortage of deceased donors. Since the first successful LDLT was performed in Australia in 1989, the shortage of donors had been partially resolved[8]. LDLT is currently considered an alternative for benign end-stage liver disease and liver malignancies. At our LT center, the frequency of LDLT is increasing. As of December 2012, 109 liver cancer patients had received LDLT at our center. However, in the early stages, the prognosis for HCC patients after LT was not satisfactory at our center due to the lack of unified criteria in mainland China. As a result, some advanced HCC patients underwent LT in those days. Some investigators in China have proposed some standards of HCC for LT, such as the Chengdu criteria (total tumor diameter ≤ 9 cm, no macro-vascular invasion, and no lymph node or extra-hepatic organ metastases) and the Hangzhou criteria (total tumor diameter ≤ 8 cm, or for total tumor diameter > 8 cm, histopathologic grade I or II and a preoperative AFP level ≤ 400 ng/mL)[26,27].

The outcomes of LDLT and DDLT for HCC are controversial. Several researchers have shown that, for HCC, the outcomes of LDLT are poorer than DDLT[19,22]. Some studies have suggested that the release of hepatotropic cytokines and the increased vascular inflow associated with hepatic regeneration may stimulate the growth of residual HCC cells, which has been the case in both animal and clinical human studies[28,29]. However, our results show that the RFS rate of LDLT for HCC is not significantly different compared to DDLT. Some authors have reported that poor outcomes may be due to the shorter waiting time and the surgical procedure for LDLT. Compared to DDLT, the waiting time for LDLT is shorter[19-21], with the latter often being referred to as “fast-track” transplantation due to this advantage[30]. Some investigators have indicated that at least 20%-30% of long-waiting candidates drop out before receiving transplantation because of tumor progression[30,31]. However, if the waiting time is short, doctors might not have adequate time to assess the biological behavior of the tumor. Thus, more patients with potentially aggressive tumors may have been selected to receive LDLT[11]. Moreover, some authors have suggested that the preoperative treatments in LDLT are not radical[18]. Our results show that there is a statistically significant difference in the preoperative adjuvant therapy between LDLT and DDLT, and that more patients received preoperative adjuvant therapy in the DDLT group. LDLT needs to preserve more of the inferior vena cava. Meanwhile, the longer hepatic artery and bile duct of the recipients should be reserved. The shorter waiting time and all of these surgical procedures may lead to the recurrence of HCC after LDLT[18].

Although LDLT is controversial for HCC, our experience indicated that there were no significant differences for either RFS or OS rates in HCC patients who underwent LDLT or DDLT at our LT center (Figure 2). The RFS and OS rates of HCC patients according to the Milan criteria were not significantly different after LDLT, while the RFS and OS rates of HCC patients according to the UCSF criteria were not significantly difference after LDLT and DDLT. We also demonstrated that the outcomes of HCC according to the Hangzhou criteria were not significantly different. Even the mean RFS and OS times for LDLT according to the different criteria were longer compared to the times for DDLT. Sandhu et al[16] reported that the type of transplant did not affect the HCC outcome. The authors demonstrated that, for HCC, RFS and long-time survival after LDLT or DDLT were similar. A study by Liang et al[15] also suggested that LDLT guarantees the same prognosis as DDLT for HCC according to the Milan criteria. Furthermore, Di Sandro et al[14] reported that LDLT guarantees the same long-term results as DDLT when the selection criteria for the candidates are the same. Although LDLT has a higher cost for the donor and the operative procedures are more complex, the overall financial burden is similar to DDLT. At the same time, LDLT can resolve issues involving allocation and the shortage of deceased donors[32-34]. Previous studies both at our own and other LT centers have demonstrated that LDLT has more advantages than DDLT, such as shorter waiting time, significantly shorter cold ischemia time, and almost no warm ischemia injury[35,36]. With these advantages, LDLT ensures that more end-stage liver disease can receive optimal and timely therapy. At our center, the “no-touch” technique, use of a 5-Fu lavage in the recipients’ peritoneal cavity, application of low-dosage immunosuppressive drugs, withdrawal of corticosteroids in the early stages, and control of HBV may play important roles in inhibiting the growth of HCC cells.

In conclusion, the results of our study demonstrate that LDLT does not increase the tumor recurrence of HCC compared to DDLT. The RFS and long-time survival times of LDLT for HCC are higher when compared to the times for DDLT. LDLT should be widely adopted in patients with benign end-stage liver disease and malignancies according to the Milan, UCSF, and Hangzhou criteria.

In the field of liver transplantation (LT), organ shortage is an urgent problem that needs to be resolved. Living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) plays an important role in combating the shortage of donated organs. However, some researchers demonstrated that tumor recurrence of LDLT was higher than deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT) for HCC.

The long-term outcomes of LDLT and DDLT for HCC are still a central issue of debate. This study included a large sample of HCC patients who received LT, of which 84 underwent LDLT. The results suggested that the recurrence-free survival and overall survival of LDLT and DDLT were similar.

These results suggest that LDLT does not increase the tumor recurrence of HCC compared to DDLT. The RFS and long-time survival times of LDLT for HCC are higher than those of DDLT.

With the current shortage of donors, LDLT should be widely adopted in patients with benign end-stage liver disease and malignancies according to the Milan, UCSF, and Hangzhou criteria.

LT is the replacement of a diseased liver with some or all of a healthy liver from another individual. LDLT: a piece of healthy liver is surgically removed from a living individual and transplanted into a recipient. DDLT: a piece or a whole liver is transplanted from an individual with brain or cardiac death into a recipient.

This current study compared the differences of RFS and overall survival of hepatitis B virus-positive HCC after living donor liver transplantation and deceased donor liver transplantation. Their results suggested that LDLT does not increase the tumor recurrence of HCC compared to DDLT. The data collection was detailed, and the analysis and results were full and accurate. The conclusion may provide some cross-references for other surgeon and investigators.

P- Reviewer: Gong JP, Guan YS S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Rutherford A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, Montalto F, Ammatuna M, Morabito A, Gennari L. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:693-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5110] [Cited by in RCA: 5309] [Article Influence: 183.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yao FY, Ferrell L, Bass NM, Watson JJ, Bacchetti P, Venook A, Ascher NL, Roberts JP. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: expansion of the tumor size limits does not adversely impact survival. Hepatology. 2001;33:1394-1403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1594] [Cited by in RCA: 1695] [Article Influence: 70.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yao FY, Ferrell L, Bass NM, Bacchetti P, Ascher NL, Roberts JP. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of the proposed UCSF criteria with the Milan criteria and the Pittsburgh modified TNM criteria. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:765-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 319] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yao FY, Xiao L, Bass NM, Kerlan R, Ascher NL, Roberts JP. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: validation of the UCSF-expanded criteria based on preoperative imaging. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:2587-2596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 382] [Cited by in RCA: 431] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mazzaferro V, Llovet JM, Miceli R, Bhoori S, Schiavo M, Mariani L, Camerini T, Roayaie S, Schwartz ME, Grazi GL. Predicting survival after liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria: a retrospective, exploratory analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:35-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1267] [Cited by in RCA: 1572] [Article Influence: 92.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Dagradi A, Munari PF, Gamba A, Zannini M, Sussi PL, Serio G. [Problems of surgical anatomy and surgical practice studied with a view to transplantation of sections of the liver in humans]. Chir Ital. 1966;18:639-659. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Smith B. Segmental liver transplantation from a living donor. J Pediatr Surg. 1969;4:126-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Strong RW, Lynch SV, Ong TH, Matsunami H, Koido Y, Balderson GA. Successful liver transplantation from a living donor to her son. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1505-1507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 604] [Cited by in RCA: 545] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lo CM, Fan ST, Liu CL, Chan SC, Wong J. The role and limitation of living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:440-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Guo L, Orrego M, Rodriguez-Luna H, Balan V, Byrne T, Chopra K, Douglas DD, Harrison E, Moss A, Reddy KS. Living donor liver transplantation for hepatitis C-related cirrhosis: no difference in histological recurrence when compared to deceased donor liver transplantation recipients. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:560-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Di Sandro S, Slim AO, Giacomoni A, Lauterio A, Mangoni I, Aseni P, Pirotta V, Aldumour A, Mihaylov P, De Carlis L. Living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: long-term results compared with deceased donor liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:1283-1285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gallegos-Orozco JF, Yosephy A, Noble B, Aqel BA, Byrne TJ, Carey EJ, Douglas DD, Mulligan D, Moss A, de Petris G. Natural history of post-liver transplantation hepatitis C: A review of factors that may influence its course. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:1872-1881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li C, Wen TF, Yan LN, Li B, Yang JY, Wang WT, Xu MQ, Wei YG. Outcome of hepatocellular carcinoma treated by liver transplantation: comparison of living donor and deceased donor transplantation. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2010;9:366-369. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Di Sandro S, Giacomoni A, Slim A, Lauterio A, Mangoni I, Mihaylov P, Pirotta V, Aseni P, De Carlis L. Living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: the impact of neo-adjuvant treatments on the long term results. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:505-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liang W, Wu L, Ling X, Schroder PM, Ju W, Wang D, Shang Y, Kong Y, Guo Z, He X. Living donor liver transplantation versus deceased donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Liver Transpl. 2012;18:1226-1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sandhu L, Sandroussi C, Guba M, Selzner M, Ghanekar A, Cattral MS, McGilvray ID, Levy G, Greig PD, Renner EL. Living donor liver transplantation versus deceased donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: comparable survival and recurrence. Liver Transpl. 2012;18:315-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lei J, Yan L, Wang W. Comparison of the outcomes of patients who underwent deceased-donor or living-donor liver transplantation after successful downstaging therapy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:1340-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fisher RA, Kulik LM, Freise CE, Lok AS, Shearon TH, Brown RS, Ghobrial RM, Fair JH, Olthoff KM, Kam I. Hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence and death following living and deceased donor liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1601-1608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lo CM, Fan ST, Liu CL, Chan SC, Ng IO, Wong J. Living donor versus deceased donor liver transplantation for early irresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2007;94:78-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kaido T, Uemoto S. Does living donation have advantages over deceased donation in liver transplantation? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1598-1603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bhangui P, Vibert E, Majno P, Salloum C, Andreani P, Zocrato J, Ichai P, Saliba F, Adam R, Castaing D. Intention-to-treat analysis of liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: living versus deceased donor transplantation. Hepatology. 2011;53:1570-1579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kulik LM, Fisher RA, Rodrigo DR, Brown RS, Freise CE, Shaked A, Everhart JE, Everson GT, Hong JC, Hayashi PH. Outcomes of living and deceased donor liver transplant recipients with hepatocellular carcinoma: results of the A2ALL cohort. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:2997-3007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Park MS, Lee KW, Suh SW, You T, Choi Y, Kim H, Hong G, Yi NJ, Kwon CH, Joh JW. Living-donor liver transplantation associated with higher incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence than deceased-donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2014;97:71-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yan LN, Li B, Zeng Y, Wen TF, Zhao JC, Wang WT, Yang JY, Xu MQ, Ma YK, Chen ZY. Modified techniques for adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2006;5:173-179. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Jiang L, Yan LN. Current therapeutic strategies for recurrent hepatitis B virus infection after liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2468-2475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zheng SS, Xu X, Wu J, Chen J, Wang WL, Zhang M, Liang TB, Wu LM. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Hangzhou experiences. Transplantation. 2008;85:1726-1732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in RCA: 379] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Li J, Yan LN, Yang J, Chen ZY, Li B, Zeng Y, Wen TF, Zhao JC, Wang WT, Yang JY. Indicators of prognosis after liver transplantation in Chinese hepatocellular carcinoma patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4170-4176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Picardo A, Karpoff HM, Ng B, Lee J, Brennan MF, Fong Y. Partial hepatectomy accelerates local tumor growth: potential roles of local cytokine activation. Surgery. 1998;124:57-64. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Shi JH, Huitfeldt HS, Suo ZH, Line PD. Growth of hepatocellular carcinoma in the regenerating liver. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:866-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yao FY, Bass NM, Nikolai B, Davern TJ, Kerlan R, Wu V, Ascher NL, Roberts JP. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of survival according to the intention-to-treat principle and dropout from the waiting list. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:873-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 312] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | Llovet JM, Bruix J. Novel advancements in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma in 2008. J Hepatol. 2008;48 Suppl 1:S20-S37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 599] [Cited by in RCA: 639] [Article Influence: 37.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lai JC, Pichardo EM, Emond JC, Brown RS. Resource utilization of living donor versus deceased donor liver transplantation is similar at an experienced transplant center. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:586-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Cheng SJ, Pratt DS, Freeman RB, Kaplan MM, Wong JB. Living-donor versus cadaveric liver transplantation for non-resectable small hepatocellular carcinoma and compensated cirrhosis: a decision analysis. Transplantation. 2001;72:861-868. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Fan ST. Live donor liver transplantation in adults. Transplantation. 2006;82:723-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Li C, Mi K, Wen Tf, Yan Ln, Li B, Yang Jy, Xu Mq, Wang Wt, Wei Yg. Outcomes of patients with benign liver diseases undergoing living donor versus deceased donor liver transplantation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Thuluvath PJ, Yoo HY. Graft and patient survival after adult live donor liver transplantation compared to a matched cohort who received a deceased donor transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:1263-1268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |