Published online Jun 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i23.3672

Revised: May 13, 2013

Accepted: May 18, 2013

Published online: June 21, 2013

Processing time: 155 Days and 0.8 Hours

AIM: To compare short- and long-term outcomes of laparoscopy-assisted and open distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer.

METHODS: A retrospective study was performed by comparing the outcomes of 54 patients who underwent laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy (LADG) with those of 54 patients who underwent open distal gastrectomy (ODG) between October 2004 and October 2007. The patients’ demographic data (age and gender), date of surgery, extent of lymphadenectomy, and differentiation and tumor-node-metastasis stage of the tumor were examined. The operative time, intraoperative blood loss, postoperative recovery, complications, pathological findings, and follow-up data were compared between the two groups.

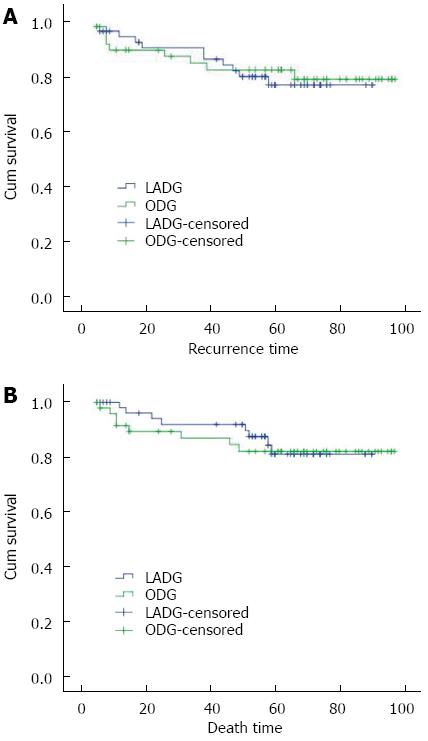

RESULTS: The mean operative time was significantly longer in the LADG group than in the ODG group (259.3 ± 46.2 min vs 199.8 ± 40.85 min; P < 0.05), whereas intraoperative blood loss and postoperative complications were significantly lower (160.2 ± 85.9 mL vs 257.8 ± 151.0 mL; 13.0% vs 24.1%, respectively, P < 0.05). In addition, the time to first flatus, time to initiate oral intake, and postoperative hospital stay were significantly shorter in the LADG group than in the ODG group (3.9 ± 1.4 d vs 4.4 ± 1.5 d; 4.6 ± 1.2 d vs 5.6 ± 2.1 d; and 9.5 ± 2.7 d vs 11.1 ± 4.1 d, respectively; P < 0.05). There was no significant difference between the LADG group and ODG group with regard to the number of harvested lymph nodes. The median follow-up was 60 mo (range, 5-97 mo). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year disease-free survival rates were 94.3%, 90.2%, and 76.7%, respectively, in the LADG group and 89.5%, 84.7%, and 82.3%, respectively, in the ODG group. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival rates were 98.0%, 91.9%, and 81.1%, respectively, in the LADG group and 91.5%, 86.9%, and 82.1%, respectively, in the ODG group. There was no significant difference between the two groups with regard to the survival rate.

CONCLUSION: LADG is suitable and minimally invasive for treating distal gastric cancer and can achieve similar long-term results to ODG.

Core tip: We retrospectively analyzed patients treated with laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy (LADG) and compared the surgical and long-term outcomes of LADG and open distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Our analysis showed that LADG has the advantages of minimally invasive surgery, rapid recovery, and fewer complications. The effect of lymph node dissection and distance of excision margin were as good as those of open gastrectomy. Long-term follow-up showed no obvious differences compared to open surgery. LADG can achieve a radical effect similar to that of open surgery.

- Citation: Wang W, Chen K, Xu XW, Pan Y, Mou YP. Case-matched comparison of laparoscopy-assisted and open distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(23): 3672-3677

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i23/3672.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i23.3672

Since Kitano et al[1] described the first early gastric cancer treated by laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy (LADG), this procedure has rapidly gained popularity in both international and domestic hospitals[2]. Although the minimally invasive effect of LADG is excellent, the therapeutic effects in adenocarcinoma still lack support from long-term follow-up studies. In this study, we performed a 1:1 case matched study to retrospectively analyze patients treated with LADG in our hospital and compared the surgical and long-term outcomes of LADG and open distal gastrectomy (ODG) for gastric cancer.

A total of 108 (1:1 matched) consecutive patients who underwent LADG (54) or ODG (54) between October 2004 and October 2007 at the General Surgery Department of Sir Run Shaw Hospital were included in this study. The patients were matched for the following parameters: gender, age (± 5 years), American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status score (ASA), time of operation (± 6 mo), extent of lymph node resection (standard D2), and differentiation and tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage of tumor. Clinical and pathological staging was determined according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (sixth edition) TNM classification scheme.

The laparoscope was introduced through a 10-mm infraumbilical trocar while the patient lay in the supine position, followed by placement of two 5-mm assistant ports in the bilateral anterior axillary line in the lower costal margin. The working port was placed to the right external rectus, 2 cm above the umbilicus through a 12-mm trocar, and another 5-mm assistant port was placed in the left corresponding position. These 5 operating trocars were placed in a V-shaped distribution. The surgeon and the second assistant (camera operator) stood on the patient’s right and the first assistant stood on the patient’s left. The procedure began with the division of the greater omentum and continued with the exposure of the right gastro-omental artery and vein along the gastroduodenal artery and intermediate vein, dissecting at their roots and the infrapyloric lymph nodes. The root of the right gastric artery was exposed along the plane of the common and proper hepatic artery and the duodenohepatic ligament and suprapyloric lymph nodes were dissected. The duodenum was dissected and transected using the endoscopic gastrointestinal anastomosis (endo-GIA) stapler after thorough dissociation of the duodenal ampulla. After retracting the stomach specimen on the left, the lymph nodes along the proximal common hepatic artery, celiac axis, and the root of the splenic artery were dissected in the order described. The root of the left gastric artery was exposed and clipped. We then opened the right diaphragmatic crura and dissected the right cardiac nodes. The stomach specimen was extracted through a 6-cm vertical median incision at the epigastrium and a Billroth II gastrojejunostomy was performed after resection of the stomach specimen.

The patients’ surgical characteristics (operative time, extent of intraoperative hemorrhage, and amount of blood transfused), postoperative recovery (time to first flatus, time to initiate oral intake, complications, and length of postoperative hospital stay), and histopathologic indices (number of resected lymph nodes, surgical margins distance) were observed and compared between the two groups. Follow-up was conducted through an outpatient service, telephone call, or mail in order to determine whether recurrences, metastasis, or death occurred.

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS®) version 16.0 (SPSS, Inc. Chicago, IL, United States). The differences in the measurement data were compared using the Student’s t test, and comparisons between groups were tested using the χ2 test or the Fisher exact probability test. The survival data were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The preoperative characteristics and postoperative pathologic features of the LADG group and the ODG group are summarized in Table 1. There were no differences with respect to preoperative characteristics and postoperative pathologic features between the two groups.

| Characteristics | LADG (n = 54) | ODG (n = 54) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 58.2 ± 11.9 | 58.4 ± 11.6 | 0.93 |

| Gender (M/F) | 40/14 | 40/14 | 1.00 |

| BMI index (kg/m2) | 22.6 ± 3.2 | 21.6 ± 3.9 | 0.15 |

| Complication (Yes/No) | 16/38 | 18/36 | 0.42 |

| ASA (I/II) | 24/30 | 24/30 | 1.00 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 3.7 ± 1.9 | 3.5 ± 1.5 | 0.17 |

| Histology (well/moderate/low/signet ring) | 19/10/14/11 | 19/10/14/11 | 1.00 |

| Lymph node metastasis (+/-) | 27/27 | 25/29 | 0.85 |

| TNM stage (IA/IB/II/IIIA/IIIB) | 22/8/9/10/15 | 22/8/9/10/15 | 1.00 |

Both surgical approaches were completed successfully with no conversion from LADG to open operation. Surgical indices are shown in Table 2. The operative time in the LADG group was longer than that in the ODG group (P < 0.01), whereas blood loss and blood infusion frequency were significantly lower (P < 0.01). There were no significant differences in the mean number of retrieved lymph nodes between the two groups.

| Variables | LADG (n = 54) | ODG (n = 54) | P value |

| Surgical indices | |||

| Operative time (min) | 259.3 ± 46.2 | 199.8 ± 40.8 | < 0.01 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 160.2 ± 85.9 | 257.8 ± 151.0 | < 0.01 |

| Intraoperative blood infusion (yes/no) | 1/53 | 13/41 | < 0.01 |

| Number of retrieved lymph nodes | 27.9 ± 7.8 | 27.7 ± 10.1 | 0.94 |

| Distance of the proximal margin (cm) | 3.6 ± 1.9 | 4.4 ± 2.1 | 0.27 |

| Distance of the distal margin (cm) | 4.3 ± 2.1 | 4.8 ± 2.3 | 0.30 |

| Postoperative recovery | |||

| First flatus (d) | 3.9 ± 1.4 | 4.4 ± 1.5 | 0.03 |

| Initiate fluid intake (d) | 4.6 ± 1.2 | 5.6 ± 2.1 | < 0.01 |

| Initiate semifluid intake (d) | 6.0 ± 1.7 | 7.4 ± 2.4 | < 0.01 |

| Hospital stay (d) | 9.5 ± 2.7 | 11.1 ± 4.1 | 0.02 |

Postoperative recovery in the two groups is shown in Table 2. The time to first flatus, time to initiate oral intake, and postoperative hospital stay were significantly shorter in the LADG group than in the ODG group (P < 0.05).

Seven (13%) patients experienced postoperative complications after LADG. One patient developed short-term gastric emptying disorder and was discharged on the 16th postoperative day after treatment with gastrointestinal decompression, gastrointestinal prokinetic agents (GIPA), and total parenteral nutrition (TPN) support therapy. One patient developed chylous fistula and was discharged 14 d after surgery following treatment with short-term fasting and TPN support. Two patients developed pulmonary infections and both patients recovered after antibiotic treatment. Three patients developed abdominal cavity effusions with complicating inflammation, one was reversed after conservative therapy, the other two were treated with abscess needle puncture and drainage under computed tomographic (CT) guidance and were discharged 16, 22, and 24 d after surgery, respectively.

Sixteen (24.1%) patients in the ODG group developed postoperative complications. One patient developed an anastomotic leak and was discharged on the 36th postoperative day after undergoing re-operation. In two patients with intra-abdominal bleeding, one was reversed after conservative therapy, the other underwent re-operation, and they were discharged 12 and 13 d after surgery, respectively. Of four patients with abdominal cavity effusions with complicating infection, one underwent laparotomy, abdominal cavity flushing drainage and was discharged 40 d after surgery, and the others were treated with abscess needle puncture and drainage under CT guidance and were discharged 18, 20, and 21 d after surgery, respectively. Three patients had pulmonary infections and all recovered after antibiotic treatment. Two patients had short-term gastric emptying disorder and were discharged on the 20th and 26th postoperative day, respectively, after treatment with gastrointestinal decompression, GIPA and TPN support. Two patients developed chylous fistula and were discharged 15 and 16 d after surgery, respectively, following treatment with short-term fasting and TPN support. Two patients had wound infections which were reversed after the incision was opened and dressed. No preoperative deaths occurred in either group. Comparisons of postoperative complications and mortality rates are summarized in Table 3.

| Variables | LADG | ODG | P value |

| Overall | 7 (13.0) | 16 (24.1) | 0.03 |

| Anastomotic leakage | 0 | 1 | |

| Anastomotic stenosis | 0 | 0 | |

| Intra-abdominal bleeding | 0 | 2 | |

| Abdominal cavity effusion complicating infection | 3 | 4 | |

| Pulmonary infection | 2 | 3 | |

| Gastric emptying disorder | 1 | 2 | |

| Chylous fistula | 1 | 2 | |

| Wound infection | 0 | 2 | |

| Reoperation | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.6) | 0.24 |

| Mortality | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.00 |

Of the 108 identified patients, 96 (88.9%) were followed up and 12 were lost to follow-up. Follow-up data were available for 49 (90.1%) and 47 (87.0%) of patients treated with LADG and ODG, respectively. The mean follow-up was 60 mo (range, 5-97 mo).

In the LADG group, 11 (20.4%) patients experienced recurrence and 8 died due to the disease: one stage IA patient developed recurrence and he is still alive 64 mo after operation. Another stage IB patient died 51 mo after operation. Two stage II patients had recurrence, one is alive 57 mo after operation, and the other died. Five stage IIIA patients experienced recurrence, four of whom died during the follow-up period, and the remaining patient is alive 56 mo after operation. Two stage IIIB patients died of the disease 14 and 59 mo after operation, respectively.

In the ODG group, nine (16.7%) patients had recurrence and 8 patients died of metastatic disease: three stage IB patients died due to the disease 9, 11, 49 mo after operation, respectively; two stage II patients experienced recurrence, one of whom died, and the other is alive 79 mo after operation; another four stage IIIA patients also had recurrence, and they died 6, 11, 15, and 31 mo after operation, respectively.

The 1-, 3-, and 5-year disease-free survival rates were 94.3%, 90.2%, and 76.7%, respectively, in the LADG group and 89.5%, 84.7%, and 82.3%, respectively, in the ODG group. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival rates were 98.0%, 91.9%, and 81.1%, respectively, in the LADG group and 91.5%, 86.9%, and 82.1%, respectively, in the ODG group. There were no significant differences in these values between the two groups (P > 0.05) (Figure 1).

Since the first successful LADG by Kitano et al[1] for early gastric cancer in 1994, the use of LADG has significantly increased in both international and domestic hospitals. More and more studies, including some randomized controlled trials, have demonstrated the advantages of LADG in the treatment of early gastric cancer such as earlier recovery of ambulation and bowel movement, less pain, and a lower rate of complications. These studies confirmed that LADG is a safe and feasible surgical method[3-5].

Kitano et al[6] reported the clinical findings of a multicenter trial which included 1491 cases of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy at 18 surgery centers, and found a complication rate of 12%, death rate of 0%, and recurrence rate of 0.4%. Prospective studies by Dulucq et al[7] revealed that postoperative complications and length of hospital stay in the LADG group were reduced compared with those in the ODG group. In the present study, complications, time to first flatus, time to initiate oral intake, and postoperative hospital stay were all significantly shorter in the LADG group than in the ODG group (P < 0.05), showing the advantages of LADG during postoperative recovery. Several publications have reported that the rate of surgical complications following LAG are in the range of 3.8%-26.7%[8-11], this rate was 13% in our study and was significantly lower than that in the ODG group. There was no preoperative death in our study; however, a recent survey showed that the mortality rate for open gastric cancer radical gastrectomy was 4%-6%[12].

Some studies have described the disadvantages of LADG compared to ODG, which include increased operative time similar to that in our study[13-16]. Operator experience, familiarity with instruments, and degree of assistant compliance are major factors influencing the operative time. During initial LADG procedures in our center, the operative time was often more than 300 min due to the above-mentioned reasons; these factors may be responsible for the significantly longer average operative time in the LADG group than in the ODG group. Other reports have also indicated that operative time with experienced surgeons was similar for LADG and ODG[17,18].

Similar to most reports, the intraoperative blood loss in the LADG group was less than that in the ODG group[5,19], as was blood transfusion, which reiterated the importance of careful laparoscopic manipulation during LADG. In addition, magnified vision also creates conditions for careful laparoscopic manipulation. Lack of blood is a common problem faced by many hospitals, especially in developing countries such as China; therefore, less invasive laparoscopic surgery can reduce the clinical requirement for blood and lower the rate of complications associated with blood transfusion such as virus infection and allergic reaction.

Radical resection of the tumor lymphatic drainage area should include complete resection and well incised margins. Laparoscopic gastric cancer D2 lymph node dissection is difficult and requires high technical expertise. Thus, whether laparoscopic techniques can be applied in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer is still controversial. However, the number of laparoscopically dissected lymph nodes is closely related to the surgical technique, and some studies have shown that there was no difference in the number of retrieved lymph nodes between LAG and OG[20,21]. Our analysis showed similar results in that D2 lymph node dissection can be completed during laparoscopy. Park et al[22] evaluated the long-term results of 239 patients who underwent LADG for the treatment of advanced gastric cancer. They found that the major recurrence was distant metastasis, whereas lymph node relapses were most frequent in para-aortic or distant lymph node metastasis; therefore, we believe that the dissection of lymph nodes around the stomach can be performed efficiently by LADG. In our study, the mean distance of the proximal and the distal margin in the LADG group was 3.6 ± 1.9 cm and 4.3 ± 2.1 cm, respectively, without residual cancer cells and no statistical difference compared with the OG group. We conclude that laparoscope-assisted radical gastrectomy may help achieve results similar to those of abdominal opening on margin distance. Port-site metastasis caused by intraoperative pneumoperitoneum of LADG is another controversial issue. Port-site metastases were not reported in our study, similar to other studies, thus we conclude that pneumoperitoneum does not contribute to a higher risk of port-site metastasis.

Whether LADG can achieve effective radical cancer excision similar to that by ODG needs to be confirmed through long-term outcomes, however, large-volume long-term studies are still lacking. In a prospective trial conducted by Huscher et al[11], the long-term results of LAG and OG were similar, but the scope of lymph node dissection was identical. A retrospective analysis conducted by Hamabe et al[23] revealed that the long-term results did not differ significantly between LAG and OG; however, because the application of LAG increased gradually, whereas the application of OG decreased gradually over the entire study period, the former had a short follow-up time. However, during the 10-year study, improvements in the chemotherapy program will certainly have an impact on the study results. Sato et al[24] analyzed the difference between OG and LAG in relation to D1, D1+, or D2 lymph node dissection using a hierarchical approach and found that the long-term results of LAG were comparable to those of OG; however, the pathological stage in the LAG group was significantly earlier than that in the OG group (P < 0.001), which seriously affected the credibility of the analysis. Pak et al[25] analyzed the follow-up of 714 patients who underwent LAG and calculated the 5-year survival rate of different TNM stages, however, their findings were not compared with those of open surgery over the same period. In addition, their follow-up duration was not long enough, as the median follow-up was less than 50 mo. Although postoperative recurrence after radical gastrectomy for cancer usually occurs within 36 mo, about 12% of cases with recurrence occur after 36 mo[26,27]. Therefore, prolonged follow-up can result in more reliable survival analysis data.

In our study, the follow-up duration was long enough as the median follow-up duration was 60 mo. In addition, we found no difference in the disease-free survival or overall survival rate between the two groups, after conducting a matched-pair design to eliminate the effects of confounding factors, including gender, age, operative period, ASA status, the extent of lymph node resection, and differentiation and TNM stage of the tumor. These results suggest that the LADG is as good as ODG with regard to long-term outcomes. The matched-pair design makes the results more credible. However, this study has several limitations, including its relatively small sample size, no survival analysis after stratification according to the TNM stage, and the use of matching research, which is a type of retrospective analysis that cannot replace prospective trials.

In conclusion, our analysis showed that LADG has the advantages of minimally invasive surgery, rapid recovery, and fewer complications. The effect of lymph node dissection and distance of excision margin were as good as those of open gastrectomy. Long-term follow-up of LADG patients showed no obvious differences compared to open surgery. We believe that LADG can achieve a radical effect similar to that of open surgery in patients with gastric cancer.

More and more studies, including some randomized controlled trials, have demonstrated the advantages of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy (LADG) in the treatment of early gastric cancer such as earlier recovery of ambulation and bowel movement, less pain, and a lower rate of complications. These studies have confirmed that LADG is a safe and feasible surgical method, but the therapeutic effects in adenocarcinoma still lack support from long-term follow-up studies.

Although the minimally invasive effect of LADG is excellent, the therapeutic effects in adenocarcinoma still lack support from long-term follow-up studies. Whether LADG can achieve effective radical cancer excision similar to that by open distal gastrectomy (ODG) requires to be confirmed through long-term outcomes, however, large-size long-term studies are still lacking.

In this study, the authors performed a 1:1 case matched study to retrospectively analyze the patients treated by LADG and compared the surgical and long-term outcomes of LADG and ODG for gastric cancer. This study showed that LADG is suitable and minimally invasive for treating distal gastric cancer and can achieve similar long-term results to ODG.

This study showed that LADG has the advantages of minimally invasive surgery, rapid recovery, and fewer complications. The effects of lymph node dissection and distance of the excision margin are as good as those of open gastrectomy. Long-term follow-up showed no obvious differences compared to open surgery. LADG can achieve a radical effect similar to that of open surgery in patients with gastric cancer. These findings are helpful in decision-making for the treatment of resectable gastric cancer.

This is a nice paper, which is worth reading and publication. The subject and findings are significant in clinical practice, especially in the field of laparoscopy-assisted surgery. Overall, the manuscript is well prepared.

P- Reviewers Catena F, Du JJ, Wang Z S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Kitano S, Iso Y, Moriyama M, Sugimachi K. Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:146-148. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Bamboat ZM, Strong VE. Minimally invasive surgery for gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:271-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lee JH, Han HS, Lee JH. A prospective randomized study comparing open vs laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy in early gastric cancer: early results. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:168-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 327] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cui M, Xing JD, Yang W, Ma YY, Yao ZD, Zhang N, Su XQ. D2 dissection in laparoscopic and open gastrectomy for gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:833-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kim HH, Hyung WJ, Cho GS, Kim MC, Han SU, Kim W, Ryu SW, Lee HJ, Song KY. Morbidity and mortality of laparoscopic gastrectomy versus open gastrectomy for gastric cancer: an interim report--a phase III multicenter, prospective, randomized Trial (KLASS Trial). Ann Surg. 2010;251:417-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 562] [Cited by in RCA: 615] [Article Influence: 41.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kitano S, Shiraishi N. Minimally invasive surgery for gastric tumors. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:151-164, xi. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dulucq JL, Wintringer P, Stabilini C, Solinas L, Perissat J, Mahajna A. Laparoscopic and open gastric resections for malignant lesions: a prospective comparative study. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:933-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tanimura S, Higashino M, Fukunaga Y, Osugi H. Laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with regional lymph node dissection for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:758-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Noshiro H, Nagai E, Shimizu S, Uchiyama A, Tanaka M. Laparoscopically assisted distal gastrectomy with standard radical lymph node dissection for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1592-1596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Usui S, Yoshida T, Ito K, Hiranuma S, Kudo SE, Iwai T. Laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: comparison with conventional open total gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2005;15:309-314. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Huscher CG, Mingoli A, Sgarzini G, Sansonetti A, Di Paola M, Recher A, Ponzano C. Laparoscopic versus open subtotal gastrectomy for distal gastric cancer: five-year results of a randomized prospective trial. Ann Surg. 2005;241:232-237. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Smith JK, McPhee JT, Hill JS, Whalen GF, Sullivan ME, Litwin DE, Anderson FA, Tseng JF. National outcomes after gastric resection for neoplasm. Arch Surg. 2007;142:387-393. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Kim YW, Baik YH, Yun YH, Nam BH, Kim DH, Choi IJ, Bae JM. Improved quality of life outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: results of a prospective randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2008;248:721-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 475] [Cited by in RCA: 503] [Article Influence: 29.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hwang SI, Kim HO, Yoo CH, Shin JH, Son BH. Laparoscopic-assisted distal gastrectomy versus open distal gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1252-1258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Han JH, Lee HJ, Suh YS, Han DS, Kong SH, Yang HK. Laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy compared to open distal gastrectomy in early gastric cancer. Dig Surg. 2011;28:245-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chun HT, Kim KH, Kim MC, Jung GJ. Comparative study of laparoscopy-assisted versus open subtotal gastrectomy for pT2 gastric cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2012;53:952-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mochiki E, Kamiyama Y, Aihara R, Nakabayashi T, Asao T, Kuwano H. Laparoscopic assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: Five years’ experience. Surgery. 2005;137:317-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lin JX, Huang CM, Zheng CH, Li P, Xie JW, Wang JB, Lu J. Laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection for advanced gastric cancer without serosa invasion: a matched cohort study from South China. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhao Y, Yu P, Hao Y, Qian F, Tang B, Shi Y, Luo H, Zhang Y. Comparison of outcomes for laparoscopically assisted and open radical distal gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy for advanced gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2960-2966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Song KY, Kim SN, Park CH. Laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection for gastric cancer: technical and oncologic aspects. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:655-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chen QY, Huang CM, Lin JX, Zheng CH, Li P, Xie JW, Wang JB, Lu J. Laparoscopy-assisted versus open D2 radical gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer without serosal invasion: a case control study. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Park do J, Han SU, Hyung WJ, Kim MC, Kim W, Ryu SY, Ryu SW, Song KY, Lee HJ, Cho GS. Long-term outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: a large-scale multicenter retrospective study. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1548-1553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hamabe A, Omori T, Tanaka K, Nishida T. Comparison of long-term results between laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy and open gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection for advanced gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1702-1709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sato H, Shimada M, Kurita N, Iwata T, Nishioka M, Morimoto S, Yoshikawa K, Miyatani T, Goto M, Kashihara H. Comparison of long-term prognosis of laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy and conventional open gastrectomy with special reference to D2 lymph node dissection. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2240-2246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Pak KH, Hyung WJ, Son T, Obama K, Woo Y, Kim HI, An JY, Kim JW, Cheong JH, Choi SH. Long-term oncologic outcomes of 714 consecutive laparoscopic gastrectomies for gastric cancer: results from the 7-year experience of a single institute. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:130-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yoo CH, Noh SH, Shin DW, Choi SH, Min JS. Recurrence following curative resection for gastric carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2000;87:236-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 523] [Cited by in RCA: 550] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |