Published online Feb 21, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i7.914

Revised: September 29, 2010

Accepted: October 6, 2010

Published online: February 21, 2011

AIM: To identify factors associated with the age at onset of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

METHODS: Five hundred and fifty-six consecutive patients positive for HCV antibody and treatment-naïve HCC diagnosed between 1995 and 2004 were analyzed. Patients were classified into three groups according to age at HCC onset: < 60 years (n = 79), 60-79 years (n = 439), or ≥ 80 years (n = 38). Differences among groups in terms of sex, body mass index (BMI), lifestyle characteristics, and liver function were assessed. Factors associated with HCC onset in patients < 60 or ≥ 80 years were analyzed by logistic regression analysis.

RESULTS: Significant differences emerged for sex, BMI, degree of smoking and alcohol consumption, mean bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) levels, prothrombin activity, and platelet counts. The mean BMI values of male patients > 60 years old were lower and mean BMI values of female patients < 60 years old were higher than those of the general Japanese population. BMI > 25 kg/m2 [hazard ratio (HR), 1.8, P = 0.045], excessive alcohol consumption (HR, 2.5, P = 0.024), male sex (HR, 3.6, P = 0.002), and GGT levels > 50 IU/L (HR, 2.4, P = 0.014) were independently associated with HCC onset in patients < 60 years. Low ALT level was the only factor associated with HCC onset in patients aged ≥ 80 years.

CONCLUSION: Increased BMI is associated with increased risk for early HCC development in HCV-infected patients. Achieving recommended BMI and reducing alcohol intake could help prevent hepatic carcinogenesis.

- Citation: Akiyama T, Mizuta T, Kawazoe S, Eguchi Y, Kawaguchi Y, Takahashi H, Ozaki I, Fujimoto K. Body mass index is associated with age-at-onset of HCV-infected hepatocellular carcinoma patients. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(7): 914-921

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i7/914.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i7.914

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common cancer in men and the eighth most common cancer in women worldwide. The incidence and mortality associated with HCC have been reported to be increasing in countries in North America, Europe and Asia. Infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is likely to play an important role in the pathogenesis of HCC[1-3]. In Japan, over 70% of cases of HCC diagnosed in the last 20 years are related to HCV infection[3].

One report estimates that 3%-35% of patients progress to cirrhosis 25 years after infection with HCV and 1%-3% progress to HCC 30 years after infection[4]. However, the factors that influence the development of HCC in patients infected with HCV remain largely unknown. Previous studies have suggested that host factors, such as sex, alcohol consumption, smoking, diabetes mellitus, and obesity, are important risk factors for HCC[5-11]. In addition, recent studies have suggested that HCV infection causes insulin resistance and leads to oxidative stress, potentiating fibrosis and hepatic carcinogenesis[12-14].

Therefore, we hypothesized that obesity influences the time to onset of HCC related to HCV infection, which is reflected in the patient’s age at onset. To test this hypothesis, we investigated the relationship between body mass index (BMI) and lifestyle factors and age at onset of HCC in HCV-infected patients.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consent on the use of clinical records for research purposes was obtained from all subjects.

From January 1995 to December 2004, 656 consecutive patients positive for HCV antibodies and diagnosed with HCC for the first time at Saga Medical School Hospital and Saga Prefectural Hospital, without prior HCC treatment, were recruited for this study. Patients were excluded from the study if they were positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (n = 8), were previously treated with interferon (n = 23), had uncontrolled ascites (n = 27), or had an advanced tumor stage accompanied by tumor thrombus in portal tract or extrahepatic metastasis (n = 42). The remaining 556 patients (351 men, 205 women), with a median age at HCC onset of 67.8 years (range, 41-92 years) were enrolled in this study.

Diagnosis of HCC was confirmed by combined ultrasonography and dynamic computed tomography (CT), dynamic magnetic resonance imaging, or CT during angiography, demonstrating a hypervascular contrast pattern of the nodule in the arterial phase and a hypovascular pattern in the portal phase. If the nodule contrast patterns were not consistent with those typical for HCC, a needle biopsy of the tumor was taken for pathological diagnosis.

Tumor stage was classified according to the 5th Edition of the General Rules for the Clinical and Pathological Study of Primary Liver Cancer, 2008, published by the Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan[15]. This classification system assumes three conditions: (1) tumor diameter of ≤ 2 cm; (2) a single tumor is present; and (3) no vascular invasion of the tumor. If all three conditions are met, the tumor is classified as stage I; if two conditions are met, it is classified as stage II; if only one condition is met, it is classified as stage III; and if none of the conditions are met, it is classified as stage IV.

At the time of HCC diagnosis, blood tests were performed and BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters (kg/m2). Prothrombin activity and serum albumin and total bilirubin levels were measured and used to determine the Child-Pugh status. Blood samples were also used to measure alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) levels and other liver function tests.

Patients were classified according to the World Health Organization (WHO) BMI criteria: underweight, BMI < 18.5 kg/m2; normal weight, BMI 18.5-25 kg/m2; overweight, BMI 25-30 kg/m2; and obese, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2[16]. Diagnosis of diabetes mellitus was made either by reviewing medical history or by assessing glucose levels with fasting plasma glucose level of ≥ 7.0 mmol/L or a 2-h plasma glucose level of ≥ 11.1 mmol/L[17]. Patients were questioned by nurses about their smoking and drinking habits during the last 10 years. We defined heavy drinking as > 60 g of alcohol consumed per day and habitual smoking as > 20 pack years.

To identify factors associated with age at onset of HCC in patients with chronic hepatitis C, we compared clinical factors in two groups of patients; those aged < 60 years at HCC onset and those aged ≥ 80 years. We then analyzed risk factors affecting earlier (onset age < 60 years) and later (onset age ≥ 80 years) development of HCC in patients with chronic HCV.

We used the Kruskal-Wallis test or the χ2 test to compare clinicopathological variables between three groups of patients. The differences in age at onset of HCC between the two groups stratified by BMI were analyzed by the Tukey-Kramer method. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify factors associated with earlier or later onset of HCC.

Data processing and analysis were performed by using the SAS (SAS Institute Inc.). Two-tailed P values of < 0.05 were considered significant.

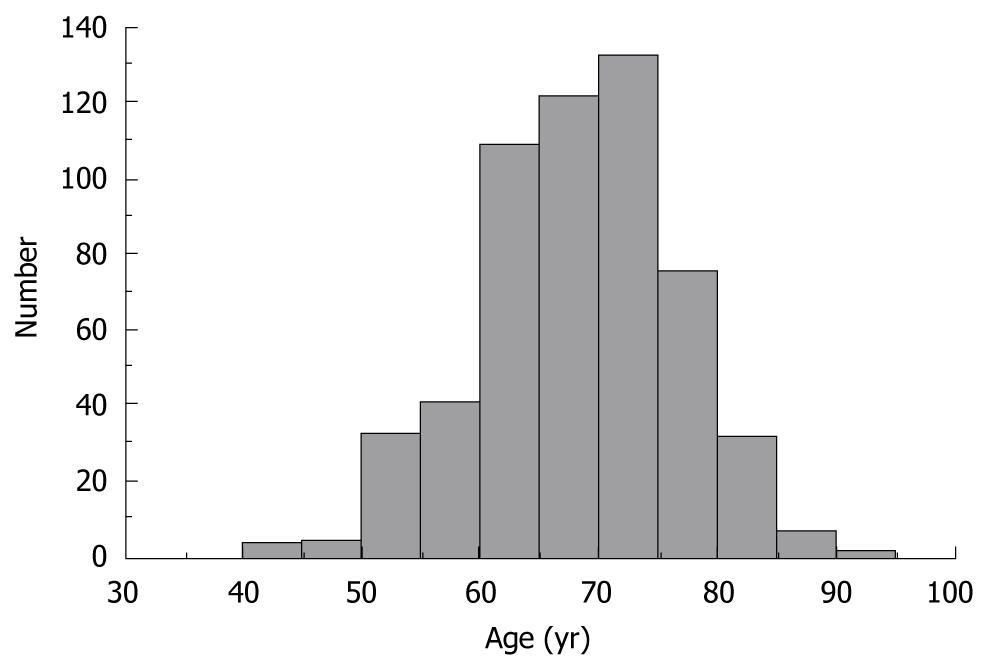

A histogram showing age at onset of HCC in 556 HCV-infected patients is depicted in Figure 1. The median age of patients was 67.8 years, with a nearly normal age distribution for the study population.

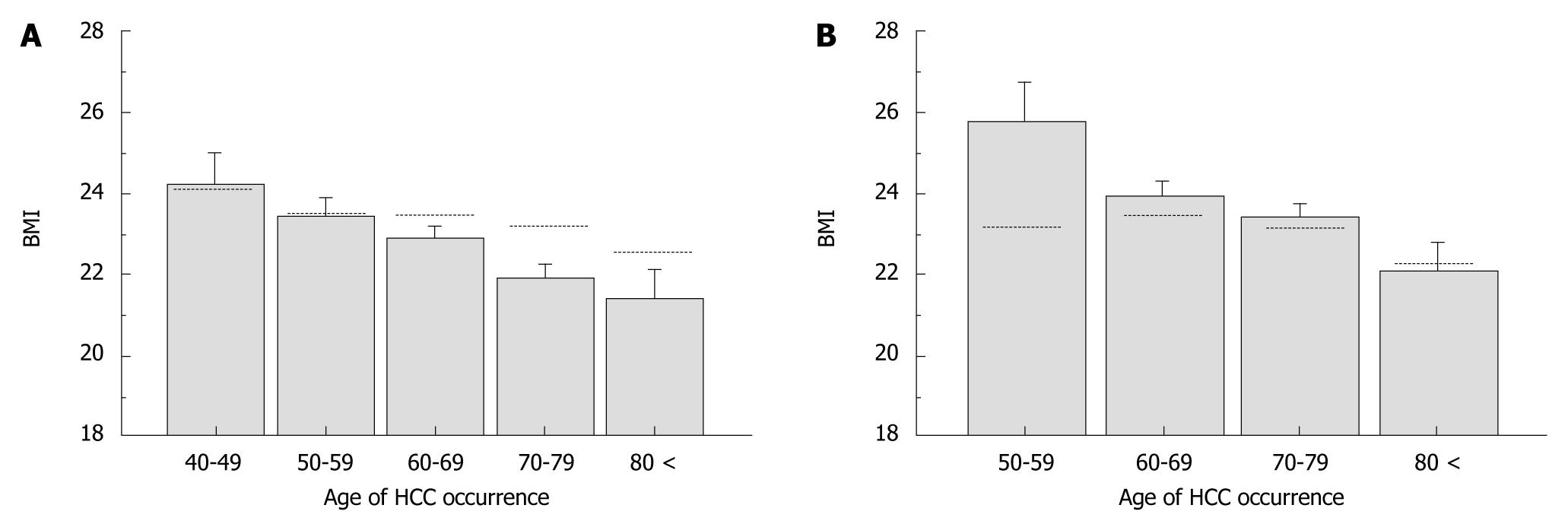

The clinical characteristics were categorized into three groups according to age at onset of HCC; < 60 years (n = 79), 60-79 years (n = 439), and ≥ 80 years (n = 38) (Table 1). Of those aged < 60 years, 88.6% were men, a much higher percentage than in those aged 60-79 years (60.1%) and those aged ≥ 80 years (44.7%). In terms of BMI, the mean value increased, and the percentage of patients with BMI < 25 kg/m2 decreased while that of patients with BMI > 25 increased with decreasing age at onset of HCC. However, this is a normal phenomenon in the general population. Therefore, we compared the mean BMI values according to the age at onset of HCC for patients in this study with BMI values of the general Japanese population in 2005 and 2006, which were published by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan (http://www.mhlw.go.jp/). The mean BMI of male HCC patients aged > 60 years was lower whereas that of female HCC patients aged < 60 years was higher than those of the general population (Figure 2). This indicates that the association between BMI and age at onset of HCC observed in this study was affected by factors independent of natural aging. We found that there were significantly more heavy drinkers (P < 0.0001) and habitual smokers (P = 0.0001) among patients aged < 60 years, compared with the other two age groups. Although the three groups did not differ in terms of Child-Pugh status, total bilirubin, ALT, and GGT levels were higher, and prothrombin activity and platelet counts were lower in patients aged < 60 years at HCC onset. No differences emerged in terms of the prevalence of diabetes mellitus or the distribution of tumor stage among the three groups.

| Factors | Occurrence age of HCC (years old) | P | ||

| <60 (n = 79) | 60-80 (n = 439) | ≥80 (n = 38) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male/Female, n | 70/9 | 264/175 | 17/21 | < 0.0001a |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.8 ± 3.4 | 22.9 ± 3.4 | 21.8 ± 3.3 | 0.02b |

| < 25/25 <, n | 50/29 | 325/114 | 32/6 | 0.039a |

| Diabetes mellitus | ||||

| With/without, n | 16/63 | 86/353 | 2/36 | 0.088a |

| Smoking (pack years) | ||||

| < 20/≥ 20, n | 43/36 | 137/302 | 9/29 | 0.0001a |

| Alcohol consumption (g/d) | ||||

| < 60/≥ 60, n | 65/14 | 416/23 | 36/2 | < 0.0001a |

| Tumor stage | ||||

| I/II/III, n | 21/33/25 | 116/196/127 | 11/16/11 | 0.981a |

| Child-Pugh class | ||||

| A/B/C, n | 55/23/1 | 349/87/3 | 34/4/0 | 0.145a |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.57 ± 0.53 | 3.64 ± 0.50 | 3.63 ± 0.41 | 0.586b |

| < 3.5/≥ 3.5, n | 30/49 | 151/288 | 14/24 | 0.433a |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.23 ± 0.62 | 1.05 ± 0.55 | 0.80 ± 0.30 | 0.0002b |

| < 2.0/≥ 2.0, n | 70/9 | 413/26 | 38/0 | 0.047a |

| Prothrombin activity (%) | 76.1 ± 16.6 | 79.9 ± 15.1 | 89.1 ± 12.2 | 0.0002b |

| < 70/≥ 70, n | 26/53 | 98/341 | 3/35 | 0.003a |

| Platelet count (× 104/μL) | 10.4 ± 7.8 | 11.0 ± 5.5 | 13.1 ± 5.8 | 0.005b |

| < 10/≥ 10, n | 45/34 | 223/216 | 14/24 | 0.125a |

| ALT (IU/L) | 78.3 ± 39.3 | 71.8 ± 44.1 | 41.7 ± 19.3 | < 0.0001b |

| < 80/≥ 80, n | 47/32 | 288/151 | 36/2 | 0.0004a |

| GGT (IU/L) | 123.7 ± 102.5 | 86.0 ± 86.6 | 54.6 ± 36.1 | < 0.0001b |

| < 50/≥ 50, n | 15/64 | 173/266 | 20/18 | 0.0002a |

We investigated risk factors associated with the development of HCC at a younger age (i.e. < 60 years of age) (Table 2). In univariate analysis, the following were found to be significant risk factors for earlier age at onset of HCC: male sex [hazard ratio (HR), 5.4; 95% CI, 2.65-11.12; P < 0.0001], BMI > 25 kg/m2 (HR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.04-2.85; P = 0.033), habitual smoking (HR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.67-4.39; P < 0.0001), heavy drinking (HR, 3.9; 95% CI, 1.93-7.87; P = 0.0002), total bilirubin > 2.0 mg/dL (HR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.00-4.96; P = 0.049), prothrombin activity > 70% (HR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.11-3.26; P = 0.019), and GGT level > 50 IU/L (HR, 3.2; 95% CI, 1.73-6.05; P = 0.0002). In multivariate analysis, independent risk factors for earlier age at onset of HCC were male sex (HR, 3.6; 95% CI, 1.58-8.13; P = 0.002), BMI > 25 kg/m2 (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.015-3.270; P = 0.045), heavy drinking (HR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.13-5.56; P = 0.024), and GGT > 50 IU/L (HR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.19-4.73; P = 0.014).

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Male | 5.43 | 2.647-11.120 | < 0.0001 | 3.58 | 1.580-8.133 | 0.002 |

| BMI | ||||||

| < 25 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥ 25 | 1.73 | 1.044-2.851 | 0.033 | 1.82 | 1.015-3.270 | 0.045 |

| Diabetes mellitus | ||||||

| Without | 1 | 1 | ||||

| With | 1.12 | 0.619-2.037 | 0.703 | 1.00 | 0.516-1.952 | 0.991 |

| Smoking (packs year) | ||||||

| < 20 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥ 20 | 2.71 | 1.669-4.393 | < 0.0001 | 1.64 | 1.904-2.991 | 0.104 |

| Alcohol (g/d) | ||||||

| < 60 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥ 60 | 3.89 | 1.926-7.874 | 0.0002 | 2.51 | 1.130-5.563 | 0.024 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | ||||||

| < 2.0 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥ 2.0 | 2.23 | 1.003-4.958 | 0.049 | 2.33 | 0.898-6.033 | 0.082 |

| Prothrombin activity (%) | ||||||

| ≥ 70 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| < 70 | 1.91 | 1.111-3.262 | 0.019 | 1.60 | 0.859-2.987 | 0.139 |

| Platelet (× 104/μL) | ||||||

| ≥ 10 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| < 10 | 1.34 | 0.829-2.166 | 0.232 | 1.60 | 0.877-2.886 | 0.118 |

| ALT (IU/L) | ||||||

| < 80 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥ 80 | 1.44 | 0.884-2.350 | 0.142 | 1.17 | 0.656-2.090 | 0.542 |

| GGT (IU/L) | ||||||

| < 50 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥ 50 | 3.24 | 1.731-6.053 | 0.0002 | 2.38 | 1.194-4.727 | 0.014 |

We also investigated factors associated with the development of HCC at an older age (i.e. ≥ 80 years of age) (Table 3). In univariate analysis, the following were significantly and negatively associated with age at onset of HCC ≥ 80 years: male sex (HR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.23-0.87; P = 0.017), diabetes mellitus (HR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.05-0.96; P = 0.043), prothrombin activity < 70% (HR, 0.1; 95% CI, 0.01-0.76; P = 0.025), ALT > 80 IU/L (HR, 0.1; 95% CI, 0.02-0.43; P = 0.002), and GGT > 50 IU/L (HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.26-0.98; P = 0.045). In multivariate analysis, ALT > 80 IU/L was the only independent factor associated with age at onset of HCC ≥ 80 years (HR, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.03-0.57; P = 0.007).

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Male | 0.45 | 0.229-0.867 | 0.017 | 0.47 | 0.200-1.119 | 0.089 |

| BMI | ||||||

| <25 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥ 25 | 0.49 | 0.201-1.201 | 0.119 | 0.48 | 0.174-1.321 | 0.155 |

| Diabetes mellitus | ||||||

| Without | 1 | 1 | ||||

| With | 0.23 | 0.054-0.957 | 0.043 | 0.32 | 0.074-1.412 | 0.133 |

| Smoking (packs year) | ||||||

| < 20 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥ 20 | 0.58 | 0.270-1.258 | 0.169 | 0.81 | 0.306-2.164 | 0.680 |

| Alcohol (g/d) | ||||||

| < 60 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥ 60 | 0.72 | 0.167-3.118 | 0.663 | 0.45 | 0.056-3.606 | 0.451 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | ||||||

| < 2.0 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥ 2.0 | 1.00 | - | 0.97 | 1.00 | - | 0.98 |

| Prothrombin activity (%) | ||||||

| ≥ 70 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| < 70 | 0.10 | 0.014-0.755 | 0.025 | 0.15 | 0.020-1.166 | 0.07 |

| Platelet (× 104/μL) | ||||||

| ≥ 10 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| < 10 | 0.54 | 0.275-1.076 | 0.080 | 0.62 | 0.287-1.360 | 0.236 |

| ALT (IU/L) | ||||||

| < 80 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥ 80 | 0.10 | 0.024-0.427 | 0.002 | 0.13 | 0.030-0.569 | 0.007 |

| GGT (IU/L) | ||||||

| < 50 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥ 50 | 0.51 | 0.262-0.984 | 0.045 | 1.01 | 0.479-2.146 | 0.971 |

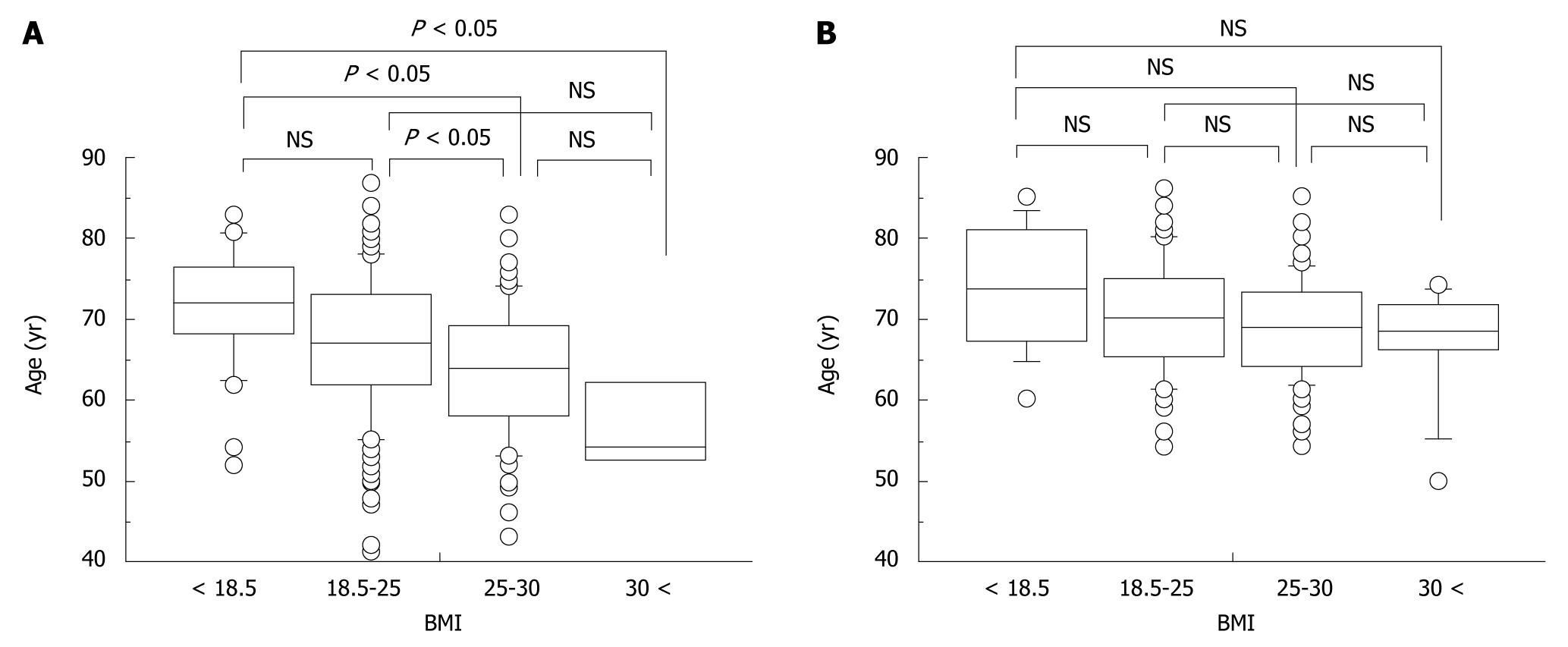

Differences in age at onset of HCC stratified by BMI were assessed in relation to sex or alcohol consumption. In men, age at onset decreased significantly with increasing BMI (mean age ± SD; underweight, 71.1 ± 7.4 years; normal weight, 67.0 ± 8.5 years; overweight, 63.6 ± 8.1 years; obese, 57.0 ± 7.0 years) (Figure 3A). Although a similar trend was noted in women, this was not significant (underweight, 73.6 ± 7.8 years; normal weight, 70.4 ± 7.0 years; overweight, 68.9 ± 6.4 years; obese, 67.0 ± 7.5 years) (Figure 3B).

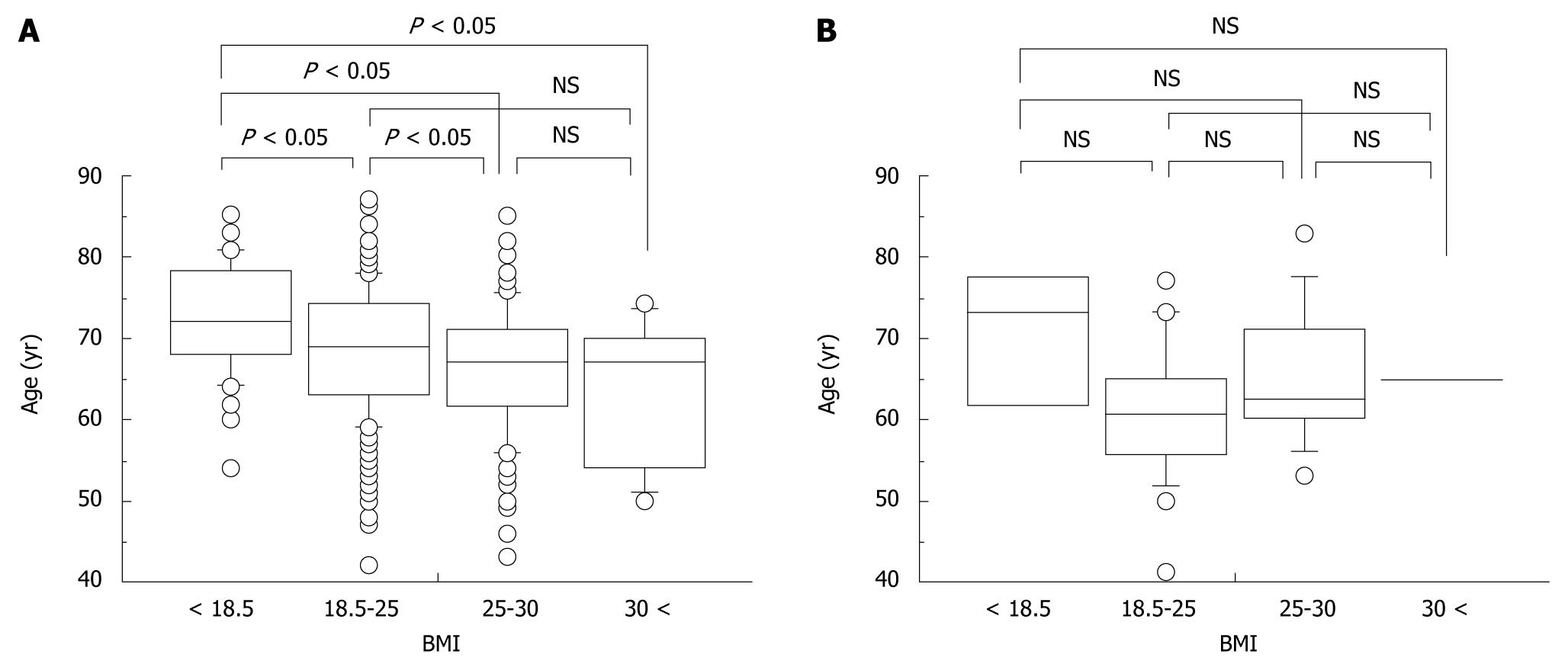

Although an association between BMI and age at onset of HCC was found among non-heavy drinkers (Figure 4A), no association was found among heavy drinkers (Figure 4B).

The results of this study revealed that higher BMI, heavy alcohol consumption, male sex, and high GGT levels are independent risk factors for younger age at onset of HCC in patients with chronic HCV infection. This study confirms the previously reported risk factors for HCC and is the first to investigate the relationship between age and HCC development.

It seems plausible that the duration of HCV infection plays a role in the age at which cirrhosis progresses to HCC. However, Hamada et al[18] reported a significant negative correlation between the time from HCV infection to onset of HCC and the patient’s age at the time of infection, and as a result, the onset of HCC was considered to occur in patients during their 60 s regardless of their age at time of infection. This indicates that factors other than duration of HCV infection may be associated with the age at onset of HCC in HCV-infected patients.

Recent studies have shown that HCV proteins, such as the core protein, cause oxidative damage by exposing the endoplasmic reticulum to oxidative stress[19-21]. Hepatic oxidative stress is strongly associated with increased risk for HCC in patients with chronic HCV[22]. Because oxidative stress is also caused by various host-related factors, it is expected to be influenced more strongly by host-related factors in HCV-infected patients than in those with HCV-negative liver disease. Indeed, we have previously reported that visceral fat accumulation was associated with greater insulin resistance in chronic HCV patients than in those with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease[23]. Therefore, it is plausible that the association between earlier onset of HCC and increased BMI is due to the generation of hepatic oxidative stress.

An interesting aspect of our results is that underweight patients, defined as those with a BMI of < 18.5 kg/m2, tended to be older at HCC onset than patients within the normal weight range (BMI 18.5-25 kg/m2). Recently, Ohki et al[11] reported that patients with a BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 had the lowest risk of developing HCC due to chronic HCV infection among all BMI groups. In general, the mortality rate associated with cardiovascular disease or cancer is higher in underweight patients than in normal weight patients[24,25]. Clearly, a larger cohort study is needed to investigate whether leanness confers a protective effect against hepatocarcinogenesis in HCV-infected patients.

Excessive alcohol consumption is also known to exacerbate hepatic oxidative stress and evoke liver fibrosis or HCC[20,26]. In this study, there was no association between BMI and age at onset of HCC in heavy drinkers. We speculate that this group may include some patients who are malnourished and possibly losing weight.

Sex modulates the natural history of chronic liver disease. Previous studies have suggested that chronic HCV infection progresses more rapidly in men than women, and that cirrhosis is predominately a disease of men and postmenopausal women[27]. Shimizu et al suggested that estrogens protect against oxidative stress in liver injury and hepatic fibrosis[28]. In this study, the effect of BMI on age at onset of HCC was more remarkable in men than women. We speculate two mechanisms to account for this difference: (1) estrogens mitigate oxidative stress or insulin resistance associated with obesity; and (2) subcutaneous fat accumulation is more dominant in obese women than visceral fat, which is known to produce several adipokines that cause insulin resistance[29].

In addition, we examined factors associated with onset of HCC at an older age (≥ 80 years). In this analysis, ALT level was the only independent factor associated with hepatocarcinogenesis in HCV-infected patients at an age ≥ 80 years. It is well known that ALT levels are associated with liver inflammation and fibrosis progression, and Ishiguro et al recently reported that elevated ALT levels were strongly associated with the incidence of HCC, regardless of hepatitis virus positivity, in a large population-based cohort study[30]. Therefore, lower ALT levels might indicate a slow course of progression of hepatic fibrosis or carcinogenesis.

A limitation of this study is that it was a cross-sectional observation, rather than a cohort follow-up study. Further studies are needed to confirm our results.

In conclusion, the results of the present study indicate that higher BMI, excessive alcohol consumption, and male sex are independent risk factors for onset of HCV-related HCC at an age of < 60 years. These results suggest that interventions to promote changes in the lifestyle of patients with chronic HCV may slow the progression of HCV infection to HCC.

The incidence and mortality associated with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have been increasing worldwide, and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection plays an important role in the pathogenesis of HCC. However, the factors that influence the development of HCC in HCV-infected patients remain largely unknown. Previous studies have suggested that host factors, such as sex, alcohol consumption, smoking, diabetes mellitus, and obesity, are important risk factors for HCC. Meanwhile, it has been reported that HCV infection causes insulin resistance and leads to oxidative stress, potentiating fibrosis and hepatic carcinogenesis. Therefore, we hypothesized that body mass index (BMI) influences the onset age of HCC related to HCV infection.

Many studies have indicated that obesity is an independent and a significant risk factor for HCC occurrence. Recently, several metabolic markers have been implicated in the development and progression of HCC.

This study indicated that higher BMI, heavy alcohol consumption, male sex, and high γ-glutamyl transpeptidase levels are independent risk factors for younger age at onset of HCV-related HCC. Interestingly, the underweight patients (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), tended to be older at HCC onset than patients within the normal weight range (BMI 18.5-25 kg/m2).

The results of this study suggest that achieving an adequate body weight along with a reduction of alcohol intake in patients with chronic hepatitis C could help prevent hepatic carcinogenesis.

The study was reasonably designed and well conducted, and the data support their conclusions.

Peer reviewers: Heitor Rosa, Professor, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Federal University School of Medicine, Rua 126 n.21, Goiania - GO 74093-080, Brazil; Jian Wu, Associate Professor of Medicine, Internal Medicine/Transplant Research Program, University of California, Davis Medical Center, 4635 2nd Ave. Suite 1001, Sacramento, CA 95817, United States

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in USA. Hepatol Res. 2007;37 Suppl 2:S88-S94. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2557-2576. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Umemura T, Ichijo T, Yoshizawa K, Tanaka E, Kiyosawa K. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44 Suppl 19:102-107. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis C in the United States. Hepatology. 2002;36:S74-S83. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Fattovich G, Stroffolini T, Zagni I, Donato F. Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: incidence and risk factors. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S35-S50. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Sinn DH, Paik SW, Kang P, Kil JS, Park SU, Lee SY, Song SM, Gwak GY, Choi MS, Lee JH. Disease progression and the risk factor analysis for chronic hepatitis C. Liver Int. 2008;28:1363-1369. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Marrero JA, Fontana RJ, Fu S, Conjeevaram HS, Su GL, Lok AS. Alcohol, tobacco and obesity are synergistic risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2005;42:218-224. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Hara M, Tanaka K, Sakamoto T, Higaki Y, Mizuta T, Eguchi Y, Yasutake T, Ozaki I, Yamamoto K, Onohara S. Case-control study on cigarette smoking and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among Japanese. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:93-97. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Polesel J, Zucchetto A, Montella M, Dal Maso L, Crispo A, La Vecchia C, Serraino D, Franceschi S, Talamini R. The impact of obesity and diabetes mellitus on the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:353-357. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Aizawa Y, Shibamoto Y, Takagi I, Zeniya M, Toda G. Analysis of factors affecting the appearance of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis C. A long term follow-up study after histologic diagnosis. Cancer. 2000;89:53-59. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Ohki T, Tateishi R, Sato T, Masuzaki R, Imamura J, Goto T, Yamashiki N, Yoshida H, Kanai F, Kato N. Obesity is an independent risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma development in chronic hepatitis C patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:459-464. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Vidali M, Tripodi MF, Ivaldi A, Zampino R, Occhino G, Restivo L, Sutti S, Marrone A, Ruggiero G, Albano E. Interplay between oxidative stress and hepatic steatosis in the progression of chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2008;48:399-406. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Koike K. Steatosis, liver injury, and hepatocarcinogenesis in hepatitis C viral infection. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44 Suppl 19:82-88. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Sheikh MY, Choi J, Qadri I, Friedman JE, Sanyal AJ. Hepatitis C virus infection: molecular pathways to metabolic syndrome. Hepatology. 2008;47:2127-2133. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Liver Cancer Study Group. The General Rules for the Clinical and Pathological Study of Primary Liver Cancer. 5th ed. Japan, 2008: 24-28. . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic; Report of a WHO Consultation on Obesity, Geneva, 3-5, June 1997. Geneva: WHO 1998; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Report of a WHO Consultation. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complication: Part1. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. World Health Organization, Department of Noncommunicable Disease Surveillance, Geneva, 1999. . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Hamada H, Yatsuhashi H, Yano K, Daikoku M, Arisawa K, Inoue O, Koga M, Nakata K, Eguchi K, Yano M. Impact of aging on the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with posttransfusion chronic hepatitis C. Cancer. 2002;95:331-339. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Tardif KD, Waris G, Siddiqui A. Hepatitis C virus, ER stress, and oxidative stress. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:159-163. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Ji C, Kaplowitz N. ER stress: can the liver cope? J Hepatol. 2006;45:321-333. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Ciccaglione AR, Costantino A, Tritarelli E, Marcantonio C, Equestre M, Marziliano N, Rapicetta M. Activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress response by hepatitis C virus proteins. Arch Virol. 2005;150:1339-1356. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Tanaka H, Fujita N, Sugimoto R, Urawa N, Horiike S, Kobayashi Y, Iwasa M, Ma N, Kawanishi S, Watanabe S. Hepatic oxidative DNA damage is associated with increased risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis C. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:580-586. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Eguchi Y, Mizuta T, Ishibashi E, Kitajima Y, Oza N, Nakashita S, Hara M, Iwane S, Takahashi H, Akiyama T. Hepatitis C virus infection enhances insulin resistance induced by visceral fat accumulation. Liver Int. 2009;29:213-220. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, Clarke R, Emberson J, Halsey J, Qizilbash N, Collins R, Peto R. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet. 2009;373:1083-1096. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Calle EE, Thun MJ, Petrelli JM, Rodriguez C, Heath CW Jr. Body-mass index and mortality in a prospective cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1097-1105. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | de la Monte SM, Yeon JE, Tong M, Longato L, Chaudhry R, Pang MY, Duan K, Wands JR. Insulin resistance in experimental alcohol-induced liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:e477-e486. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Farinati F, Sergio A, Giacomin A, Di Nolfo MA, Del Poggio P, Benvegnù L, Rapaccini G, Zoli M, Borzio F, Giannini EG. Is female sex a significant favorable prognostic factor in hepatocellular carcinoma? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1212-1218. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Shimizu I, Ito S. Protection of estrogens against the progression of chronic liver disease. Hepatol Res. 2007;37:239-247. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Geer EB, Shen W. Gender differences in insulin resistance, body composition, and energy balance. Gend Med. 2009;6 Suppl 1:60-75. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Ishiguro S, Inoue M, Tanaka Y, Mizokami M, Iwasaki M, Tsugane S. Serum aminotransferase level and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a population-based cohort study in Japan. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2009;18:26-32. [Cited in This Article: ] |