INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) is a lesion composed of myofibroblastic spindle cells, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and eosinophils. It can occur in soft tissues and visceras[1]. It was previously called plasma cell granuloma, inflammatory myofibrohistiocytic proliferation and inflammatory pseudotumor, but IMT is the designation currently used[1]. IMT is more frequently described in the lung and abdomen of young patients, but it can also be found in the central nervous system, salivary glands, larynx, bladder, breast, spleen, skin and liver[1].

Pack and Backer published the first case occurring in the liver[2]. Since then, reports on IMT in the liver with different progression have been described[3]. Concerning pathogenesis, it is controversial whether IMT is a neoplasm or a reactive pseudotumoral lesion[4]. The inflammatory pseudotumor has been associated with trauma, auto-immune disease, and infectious disease[5-9]. Recently, anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene translocations or ALK protein expression in IMT has been reported, mainly in young patients[10].

Differential diagnosis of malignant disease is sometimes difficult. The clinical presentation is frequently associated with local mass and upper abdominal pain, as well as jaundice, intermittent fever, and weight loss[1,11]. Surgical resection is the principal treatment, but corticosteroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory therapy are sometimes used[12].

Here, we report on a case of a large incompletely resected IMT, with local recurrence and kidney and diaphragm infiltration on routine surveillance two years later.

CASE REPORT

A 40-year-old Brazilian woman born in northeast Brazil, presented with abdominal pain, fatigue and weight loss of 2 kg. She denied having fever or abdominal trauma, and she was receiving oxamniquine therapy for hepatic schistosomiasis. On physical exam, she presented with a hard mass that occupied the superior right quadrant of the abdomen and was painful at superficial and deep palpation. It was difficult to distinguish it from the liver that seemed enlarged primarily in its right lobe. Laboratory exams showed a cholestatic pattern, with elevated alkaline phosphatase (1176 U/L) and γ glutamyl transpeptidase (1341 U/L). The aminotransferases were also abnormal (aspartate transaminase = 108 mg/dL and alanine transaminase 92 mg/dL). Alpha-feto-protein, CEA, CA19.9 and CA125 levels were all normal.

At the ultrasound exam, a large isoechoic mass was identified in the 5th, 6th and 8th segments of the liver, and there was no mechanical obstruction of the biliary tract. Abdominal computer tomography (CT) confirmed its localization in the liver and described a close contact with the inferior caval vein. Laparotomy was indicated, and a right lobectomy of the liver was performed, but the tumor was incompletely resected because it was in contact with a large vessel. Two years later, routine CT scan detected local recurrence with diaphragm infiltration and a well defined mass in the right kidney. Again, the tumor was partially resected (including a right nephrectomy).

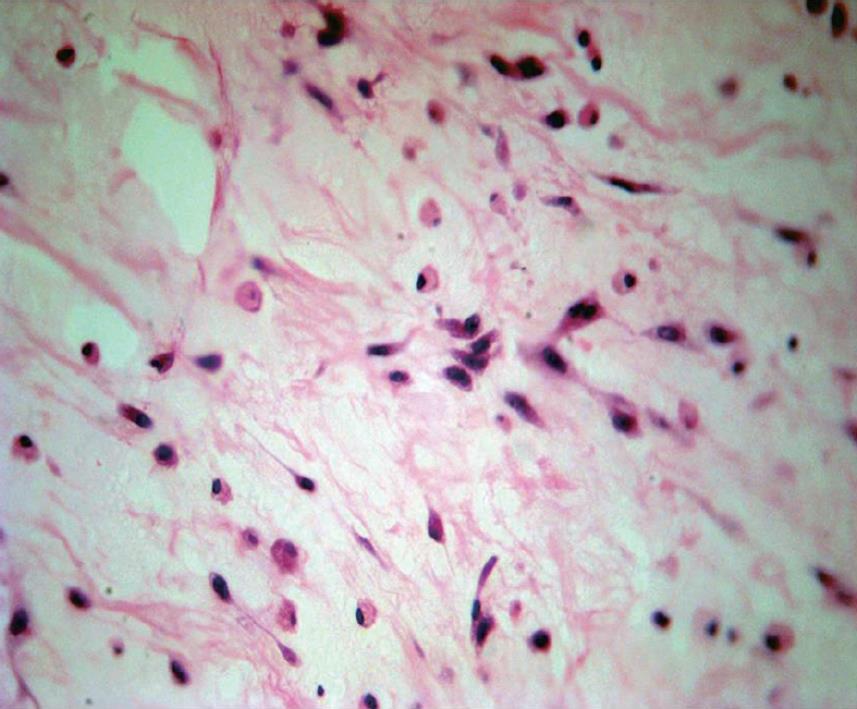

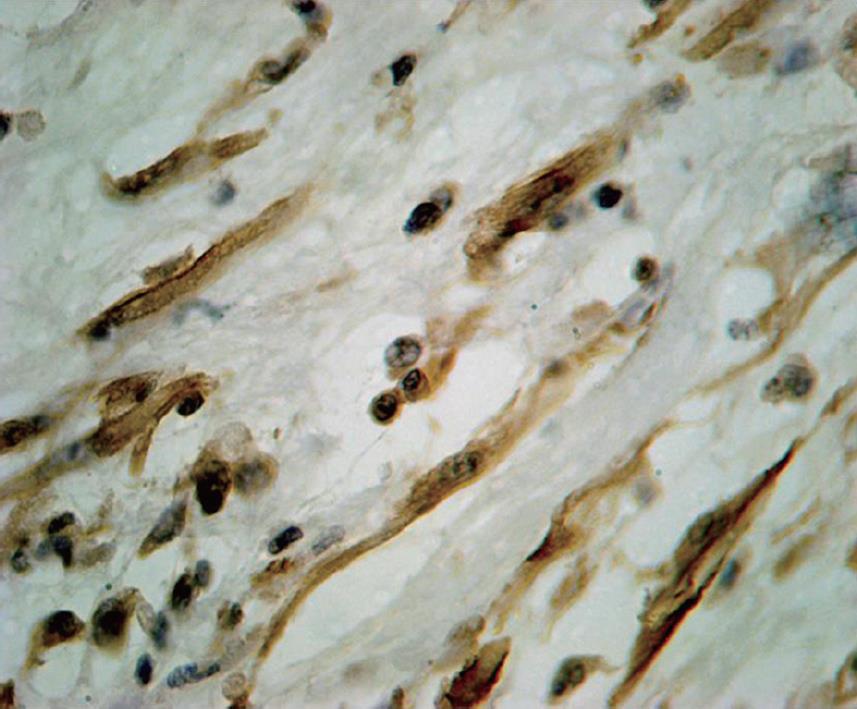

The gross appearance revealed a right hepatectomy specimen with a large mass measuring 11 cm (Figure 1) and other multinodular masses measuring 31 cm × 23 cm × 10 cm (Figure 2), which altogether weighed 3 kg. Those lesions were well circumscribed, and the cut surface was whorled, firm, and shining, with a myxoid aspect and a whitish or yellowish appearance (Figures 1 and 2). The adjacent liver parenchyma was unremarkable. Histologically, the tumor was characterized by spindle cell proliferation with plasmocytes, lymphocytes, histiocytes, and a few neutrophils, dispersed in a myxoid or dense collagen background (Figure 3). Cellular atypia was not identified, neither were mitotic or necrotic areas, and staining did not show the presence of microorganisms. By immunohistochemical analysis, the spindle cells were uniformly positive for vimentin and smooth muscle actin (SMA), supporting the myofibroblastic nature of these cells (Figure 4). There was no reactivity for CD34, CD23, CD117, EBV, P53 and ALK1. The CD68 was positive in histiocytes. In the liver parenchyma, granulomatous lesions with viable eggs of Schistosoma mansoni were identified in the portal tracts. The right kidney showed a large mass in its upper portion measuring 19 cm × 16 cm × 15 cm with the same macroscopic, microscopic and immunohistochemical findings as those described in the liver tumors.

Figure 1 Well circumscribed and nodular mass, tan-white.

Figure 2 Multinodular mass, tan-white and shining.

Figure 3 Spindle and inflammatory cells in a myxoid background (HE stain, × 100).

Figure 4 Smooth muscle actin positive in the spindle cell tumor (immunostaining, × 200).

DISCUSSION

IMT is a lesion with intermediate biological behavior that may recur with local or surrounding infiltration or rarely metastasizes. Its usual radiological aspects are similar to those of a malignant neoplasm[13]. It is described in almost all solid organs, including the liver. Patients with hepatic IMT may complain of abdominal pain, jaundice and obliterative phlebitis, but, in this report, the clinical symptoms were nonspecific. As described in the laboratory setting, we observed a cholestatic laboratory pattern suggestive of an infiltrative liver disease. The aminotransferases were fairly abnormal and the radiological exams suggested a malignant tumor.

The pathogenesis of IMT is uncertain. Some cases are related to infectious or reparative processes, and the association of IMT with some infectious agents has been related to its pathogenesis, although it is rarely observed. Parasitic infections were also implicated, as Schistosoma mansoni[6] were identified in the midst of the tumor tissue. In this instance, we are not sure whether the hepatic schistosomiasis is an incidental diagnostic finding or if it is associated with the pathogenesis of the lesion, even though numerous slides demonstrated viable eggs of Schistosoma mansoni not in the tumor but, rather, in the adjacent liver tissue. Abdominal and intestinal pseudotumors have been described as a complication of this parasitosis[14]. In the liver, Schistosoma mansoni maturation is finished in the intra-hepatic portion of the portal vein, leading to a pyelophlebitis and to a granulomatous peri-pyelophlebitis together with a de novo formation of a portal conjunctive[15]. According to some authors[16], the IMT could develop secondary portal venous infection, and the inflammatory mass might have enlarged together with the obliterating phlebitis, which might possibly explain the tumoral development in this patient. However, there are tumors with evidence of being truly neoplastic, characterized by rearrangements involving chromosome 2q23 upon which the ALK gene is located[17].

As already described in the literature[1], this tumor was found in the right lobe of the liver, characterized by a well-circumscribed lesion that was firm, with myxoid areas, and a yellow or whitish color. The differential diagnosis depends upon the histological patterns observed, and, although we observed a hypocellular fibrous pattern with some inflammatory cells, the SMA immunoreactivity in the spindle cell was important in the diagnosis. CD34, CD23 and CD117 were non-immunoreactive in the spindle cells, which excluded the diagnosis of fibrous solitary tumor, follicular dendritic cell tumor and gastrointestinal stromal tumor, respectively. What draws our attention in this case report is the tumor progression showing right kidney and diaphragm infiltration (benign histological features were also observed in infiltrative lesions) in addition to the same immunohistochemical pattern observed in the primary tumor. Morphological and genetic features have been studied as prognostic factors, and this case report did not show such features as p53 immunoreactivity, ganglion-like cells, and mitotic figures, which are sometimes associated with aggressive tumors[4]. Although clinical, histopathological or molecular features do not predict biological behavior[4,11], recurrences are associated with abdominal site, large size of the tumor and older age. In general, histological features are not different between ALK positive and negative inflammatory pseudotumors[18]. Cases with local recurrence and an aggressive clinical course have also been described, especially in patients with incomplete resection[19]. This was probably the main reason for the aggressive clinical and biological course observed in this case because, aside from the large size, the proximity between the tumor and the vital structures such as the vena cava did not allow the complete resection of the tumor. Finally, the histological patterns did not predict the aggressive biological behavior, and further investigation is necessary in order to better clarify an infectious cause in some cases of IMT.

Peer reviewer: Diego Garcia-Compean, MD, Professor, Faculty of Medicine, University Hospital, Department of Gastroenterology, Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon, Ave Madero y Gonzalitos, 64700 Monterrey, NL, México

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor O'Neill M E- Editor Lin YP