Published online May 14, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i18.2298

Revised: February 18, 2010

Accepted: February 25, 2010

Published online: May 14, 2010

Aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms of the superior mesenteric artery are potentially lethal and should be treated as urgently as possible. In a 52-year-old man with occasional epigastric pain, we accidentally discovered a superior mesenteric artery aneurysm that was ruptured with spontaneous tamponade in the uncinate process and in the head of the pancreas. The ruptured aneurysm had a heterogeneous appearance due to its thrombotic and hemorrhagic content, and it simulated a voluminous mass in the head and uncinate process of the pancreas, associated with mild dilatation of the main pancreatic duct. Recent advances in multidetector computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging have enabled radiologists to develop a correct diagnosis of mesenteric aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms of the visceral branches of the abdominal aorta, and to differentiate this diagnosis from that of pancreatic or peripancreatic masses; angiography is currently used to confirm a diagnosis and to develop therapeutic treatments.

- Citation: Palmucci S, Mauro LA, Milone P, Di Stefano F, Scolaro A, Di Cataldo A, Ettorre GC. Diagnosis of ruptured superior mesenteric artery aneurysm mimicking a pancreatic mass. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(18): 2298-2301

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i18/2298.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i18.2298

Aneurysms of the visceral branches of the abdominal aorta are rare and potentially life-threatening, with a documented prevalence of 0.1%-2%[1]. The superior mesenteric artery is the third most common site of splanchnic aneurysm[2]. Recent advances in computed tomography (CT) vascular imaging and magnetic resonance angiography have provided a highly accurate representation of abdominal splanchnic vessels[3]. Multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT) with 3D post-processing allows for an accurate representation of vascular course and caliber. Thanks to its high-contrast resolution, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used to determine the composition of aneurysmatic masses.

The aim of this case report is to describe the imaging features of a ruptured superior mesenteric artery aneurysm, which created a giant hematoma and mimicked a pancreatic mass, with mild dilatation of main pancreatic duct.

A 52-year-old man with intermittent epigastric pain was admitted to our hospital. He had undergone cholecystectomy and left colonic resection for cancer of the large intestine 4 and 2 years earlier, respectively. Preoperative liver ultrasonography and chest X-rays performed during previous hospitalization were normal.

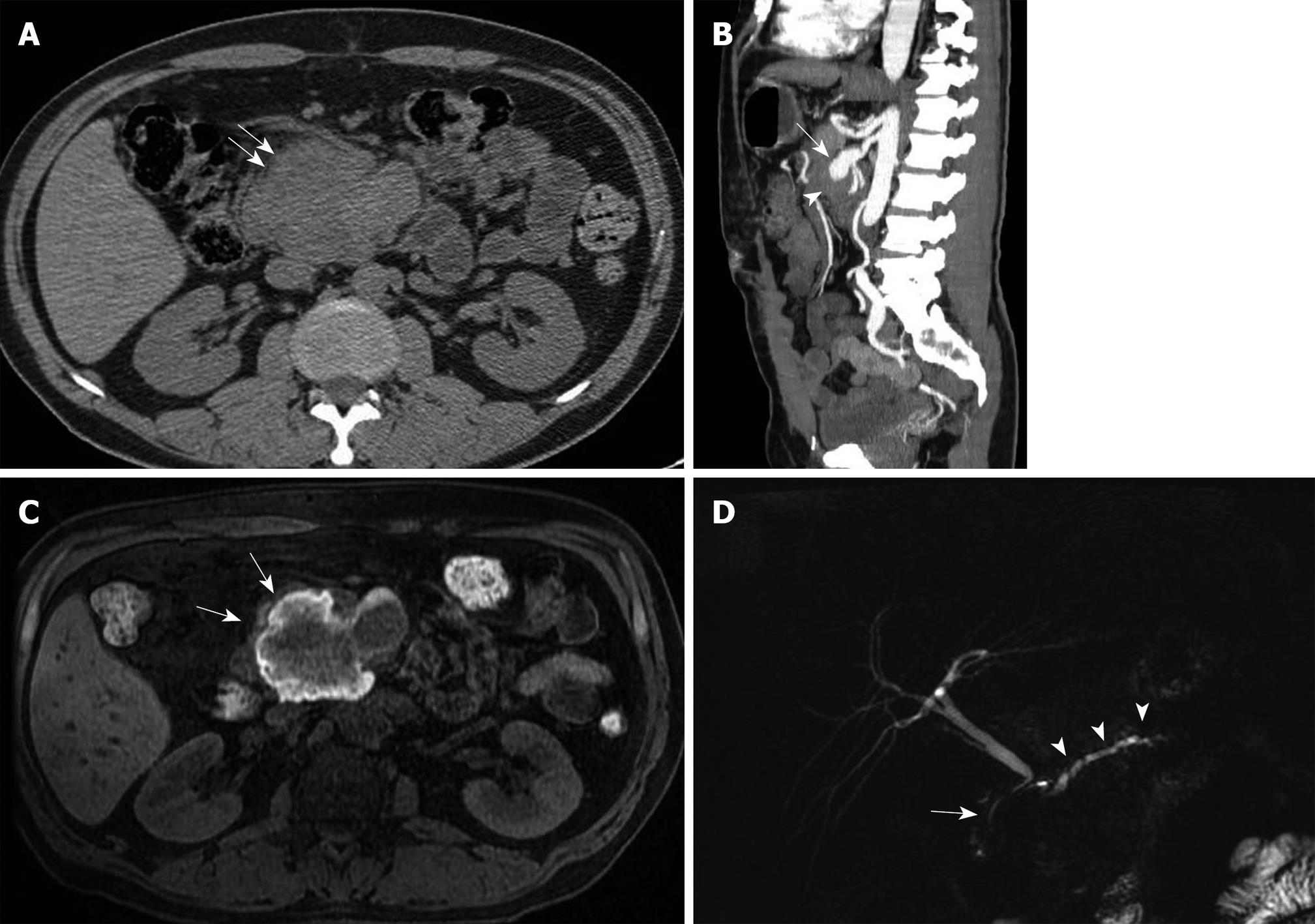

During his last hospital admission, the patient underwent laboratory tests that revealed a mild increase in serum pancreatic amylase and lipase activity (129 and 116 UI/L, respectively). Coagulation tests were normal, and clinical examination did not reveal significant results. The patient was scheduled for abdominal CT. MDCT showed an 8.2 cm × 6.6 cm mass in the area of the uncinate process of the pancreas (Figure 1A). A post-contrast infusion MDCT scan showed enlargement of the proximal portion of the superior mesenteric artery, which had a transverse diameter of 2.2 cm. Multiplanar reconstructions of MDCT images indicated communication of the mass with the enlarged superior mesenteric artery (Figure 1B). The artery was englobed into the mass, which resulted in its complete obstruction. Liver, spleen and kidneys were normal, as was the small bowel, as shown by CT. CT did not show any relapse or residual sign in the area where surgical anastomosis of the colon had been performed.

Enhanced and unenhanced MRI was performed to investigate the mass composition. T1-weighted MR images showed heterogeneous high signal content (Figure 1C); a low peripheral “rim sign” on T1 and T2 images was revealed. Post-gadolinium images confirmed the enlarged superior mesenteric artery and its communication with the mass; there was no significant contrast enhancement in the mass itself. The initial diagnostic hypothesis was of a giant mass of the pancreas, which involved the superior mesenteric artery. The radiologist who performed the examinations described “an expansive lesion in the pancreatic area involving the proximal tract of the superior mesenteric artery”, whereas the mass was caused by development and fissuration of the aneurysm into the uncinate process of the pancreas.

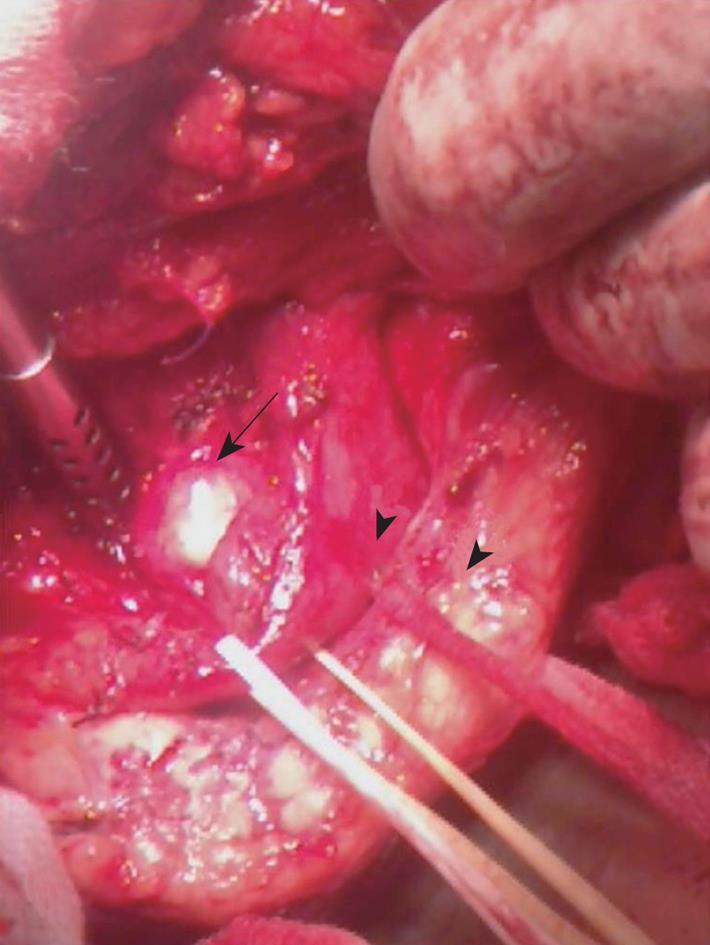

Angiography confirmed dilatation of the superior mesenteric artery, without any sign of bleeding. The patient underwent surgical intervention with resection of the thrombotic clot-filled aneurysm (Figure 2), which ruptured with spontaneous tamponade in the pancreatic region and formed a giant hematoma; bowel vitality was good during the provocative occlusive test, and subsequent ligation of the superior mesenteric artery was performed. Distal pancreatectomy was also required for the retropancreatic extension of the hematoma. MDCT performed 6 mo later did not show any complications.

Early diagnosis and treatment of aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms of the superior mesenteric artery are essential to prevent them from rupturing and threatening patients’ lives[4]. Etiology includes arteriosclerosis, fibromuscular dysplasia, connective tissue disease, infection, and arterial dissection[1,5]. Mycotic aneurysms affect the superior mesenteric artery in 33%-66% of cases[6]. Superior mesenteric artery pseudoaneurysms are often associated with chronic pancreatitis, or they can be a consequence of external or iatrogenic trauma[5,7].

We describe a case of superior mesenteric artery aneurysm which ruptured with spontaneous tamponade in the uncinate process and head of the pancreas, which mimicked a pancreatic mass on MDCT and MRI. The etiology of the superior mesenteric aneurysm in our patient has still not been established; a previous history of pancreatitis, vascular hypertension, connective disease or traumatic abdominal injury was not revealed.

It is known that, on unenhanced MDCT, a superior mesenteric aneurysm can simulate a pancreatic mass[8]; thrombotic or hemorrhagic material in the aneurysm sac provides heterogeneous signal intensity. In our case, the sac filled with blood clots showed a heterogeneous elevated signal on T1 images, which suggested the possibility of a mass with hemorrhagic content or a hematoma.

Without contrast enhancement during the arterial phase, it is very difficult to establish the vascular nature of aneurysms, which is why the radiologist made an incorrect diagnosis[9]. The radiologist who first described MDCT and MRI signs did not explore the vascular structures with multiplanar reconstructions and hypothesized aneurysm not as a primary diagnosis, but as a consequence of a giant mass in the pancreatic tissue. Initially, he did not consider the possibility of a fissurated aneurysm. Pre-angiographic evaluation of multiplanar reconstruction, performed with other colleagues, finally oriented him towards diagnosing a giant aneurysm ruptured into the uncinate process. Axial images and CT reconstructions showed the continuity of the mass and the superior mesenteric artery, and enabled radiologists to diagnose a vascular aneurysm.

There is a large group of peripancreatic structures that can simulate pancreatic cystic lesions, such as aneurysms of the superior mesenteric artery, superior mesenteric vein, hepatic artery and portal vein[10]. Large aneurysms compress the duodenum and biliary duct, thus causing obstructive jaundice[7]. In our case, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) showed the dislocation of the pancreatic tract of the main biliary duct, which was caused by the large ruptured aneurysmatic sac (Figure 1D). The choledochus had a caliber of approximately 1 cm, but this was not considered a significant feature since the patient had been cholecystectomized; a diameter of up to 1 cm is frequent in such patients. Dilatation of the main pancreatic duct has not been reported very frequently in the literature. MRCP showed moderate dilatation of the main pancreatic duct and mild ectasia of the side branches of the main pancreatic duct (Figure 1D). The dilatation of the pancreatic duct was caused by the hemorrhagic sac, with evident dislocation of pancreatic parenchyma. Mild compression of the main pancreatic duct by the aneurysm sac can also explain minimally increased values of amylase and lipase activity discovered through laboratory tests, which initially physicians interpreted as symptoms of pancreatic disease.

Contrast administration is necessary to demonstrate a patent lumen, and suggests the correct diagnosis. Recent advances in CT technology have allowed for a more accurate multiplanar and 3D reconstruction, which shows the communication between the aneurysm sac and the blood vessels. High table-speed and rapid image acquisition during contrast injection clearly show the arterial anatomy. On CT, large aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms can simulate pancreatic pseudocysts with fluid content[11]. Blood clots and thrombotic deposits in aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms have a density similar to that of soft tissues or of high-density fluid collections. In some cases, pseudocysts have a hemorrhagic content, and on unenhanced CT scans, their density is the same as that of aneurysms.

MRI is very useful in terms of diagnosis because it provides radiologists with accurate information on mass composition: on T1-weighted images the presence of thrombotic and hemorrhagic material is easily demonstrated by the high-signal content of the mass. However, these features are not specific. Since hemorrhagic content on unenhanced T1 images can also be found in mucinous cystic neoplasms, a differential diagnosis is called for. Mucinous cystic lesions have variable signal intensity and sometimes proteinaceous material provides hyperintensity on T1-weighted images. Post-gadolinium images did not reveal internal septa and were very helpful in differentiating the diagnosis from that of cystic mucinous lesions.

In conclusion, aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms of the superior mesenteric artery at the pancreas level can be very insidious for radiologists because they can mimick pancreatic masses. Significant advancements in 3D and multiplanar imaging software have made it possible to obtain high-resolution images of the abdominal aorta and its branches: radiologists need to keep in mind the diagnostic value of multiplanar reconstructions.

Peer reviewer: Xiao-Peng Zhang, Professor, Department of Radiology, Peking University School of Oncology, Beijing Cancer Hospital & Institute, No. 52 Haidian District, Beijing 100142, China

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Tulsyan N, Kashyap VS, Greenberg RK, Sarac TP, Clair DG, Pierce G, Ouriel K. The endovascular management of visceral artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:276-283; discussion 283. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Yüksel M, Islamoğlu F, Egeli U, Posacioğlu H, Yilmaz R, Büket S. Superior mesenteric artery aneurysm. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2002;10:61-63. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Grierson C, Uthappa MC, Uberoi R, Warakaulle D. Multidetector CT appearances of splanchnic arterial pathology. Clin Radiol. 2007;62:717-723. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Ku A, Kadir S. Embolization of a mesenteric artery aneurysm: case report. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1990;13:91-92. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Messina LM, Shanley CJ. Visceral artery aneurysms. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:425-442. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Saftoiu A, Iordache S, Ciurea T, Dumitrescu D, Popescu M, Stoica Z. Pancreatic pseudoaneurysm of the superior mesenteric artery complicated with obstructive jaundice. A case report. JOP. 2005;6:29-35. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Nosher JL, Chung J, Brevetti LS, Graham AM, Siegel RL. Visceral and renal artery aneurysms: a pictorial essay on endovascular therapy. Radiographics. 2006;26:1687-1704; quiz 1687. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Lawler LP, Horton KM, Fishman EK. Peripancreatic masses that simulate pancreatic disease: spectrum of disease and role of CT. Radiographics. 2003;23:1117-1131. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | To'o KJ, Raman SS, Yu NC, Kim YJ, Crawford T, Kadell BM, Lu DS. Pancreatic and peripancreatic diseases mimicking primary pancreatic neoplasia. Radiographics. 2005;25:949-965. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Barkin JS, Potash JB, Hernandez M, Casillas J, Morillo G. Hepatic artery aneurysm simulating a cystic mass of the pancreas. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32:1196-1200. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Buetow PC, Rao P, Thompson LD. From the Archives of the AFIP. Mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1998;18:433-449. [Cited in This Article: ] |