Published online Feb 28, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i8.1271

Revised: December 20, 2006

Accepted: January 29, 2007

Published online: February 28, 2007

We describe a rare case of the transformation of a dysplastic nodule into well-differentiated hepato-cellular carcinoma (HCC) in a 56-year-old man with alcoholrelated liver cirrhosis. Ultrasound (US) disclosed a 10 mm hypoechoic nodule and contrast enhanced US revealed a hypovascular nodule, both in segment seven. US-guided biopsy revealed a high-grade dysplastic nodule characterized by enhanced cellularity with a high N/C ratio, increased cytoplasmic eosinophilia, and slight cell atypia. One year later, the US pattern of the nodule changed from hypoechoic to hyperechoic without any change in size or hypovascularity. US-guided biopsy revealed well-differentiated HCC of the same features as shown in the first biopsy, but with additional pseudoglandular formation and moderate cell atypia. Moreover, immunohistochemical staining of cyclase-associated protein 2, a new molecular marker of well-differentiated HCC, turned positive. This is the first case of multistep hepatocarcinogenesis from a dysplastic nodule to well-differentiated HCC within one year in alcohol-related liver cirrhosis.

- Citation: Kim SR, Ikawa H, Ando K, Mita K, Fuki S, Sakamoto M, Kanbara Y, Matsuoka T, Kudo M, Hayashi Y. Multistep hepatocarcinogenesis from a dysplastic nodule to well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma in a patient with alcohol-related liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(8): 1271-1274

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i8/1271.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i8.1271

In Western countries and in Japan, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) usually develops in close association with pre-existing liver cirrhosis (LC). The cirrhotic liver is therefore believed to have a precancerous lesion recognizable as a small nodule, referred to as the dysplastic nodule[1] or adenomatous hyperplasia[2]. The mean size of most dysplastic nodules is 7-8 mm, seldom larger than 20 mm in diameter. Among LC cases, the dysplastic nodule is usually hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related, rarely hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related, and has not been reported as alcohol-related. HCC usually develops in chronic liver diseases such as HCV and HBV. In Japan, HCC occurs in 81% of HCV and 14% of HBV carriers[3], but seldom in alcohol-related LC, whereas in the United States HCC occurs in 30% of alcohol-related LC[4]. Herein we describe a rare case of multistep hepatocarcinogenesis from a dysplastic nodule to well-differentiated HCC in a patient with alcohol-related LC.

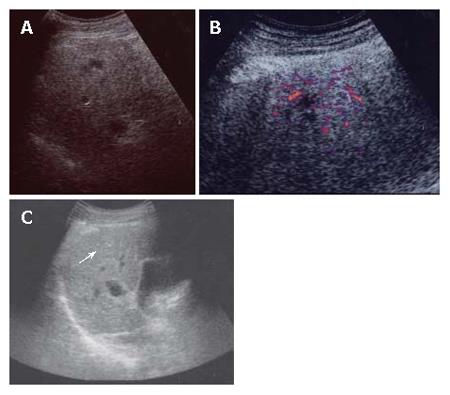

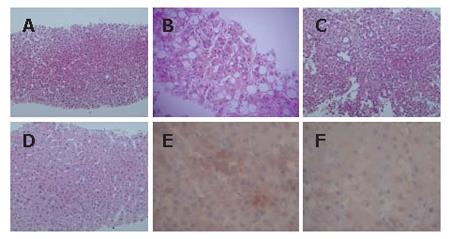

A 56-year-old man was admitted to Kobe Asahi Hospital in April 2005 for further examination of a 10 mm hypoechoic nodule in the liver. In April 2001, histologic analysis of tissue obtained at biopsy because of his abnormal liver function had revealed alcohol-related LC (Figure 1); no nodule was detected. His alcohol consumption over 35 years was 120 mL/d. A physical examination on admission in April 2005 showed no remarkable abnormalities. There was no evidence of lymph adenopathy or splenomegaly. The serum was negative for HCV antibody (anti-HCV), hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), and hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc). Laboratory data on admission in April 2005 disclosed the following abnormal values: platelets 7.1 × 104/μL (normal 13.1-36.2), aspartate aminotransferase 88 IU/L (8-38), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GTP) 677 IU/L (16-84), total bilirubin 1.4 mg/dL (0.2-1.0), and indocyanine green (ICG) 15 min retention rate 35% (0%-10%). Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), lens culinaris agglutinin A-reactive fraction of alpha fetoprotein (AFP L3) and protein-induced vitamin K absence (PIVKA II) were within normal ranges. Immunological examinations revealed the following: IgG 1452 mg/dL (870-1700), IgM 235 mg/dL (33-190), IgA 207 mg/dL (110-410), B cell 8% (14%-13%), T cell 83% (66%-89%), CD4/CD8 ratio 2.08 (0.40-2.30), and NK cell activity 50% (18%-40%). Ultrasound (US) disclosed a 10 mm hypoechoic nodule in segment seven (S7) (Figure 2A). Plain computed tomography (CT) did not show any nodule, and contrast enhanced CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) did not reveal any enhanced nodule. MRI revealed an isointensive nodule at both T1- and T2-weighted sequences. CT hepatic arteriography (CTA) did not show any enhanced nodule, and CT during arterial portography (CTAP) did not show any perfusion defect. Contrast enhanced US revealed a hypovascular nodule (Figure 2B). A US-guided biopsy revealed a high grade dysplastic nodule characterized by increased cellularity with a high N/C ratio, increased cytoplasmic eosinophilia, and slight cell atypia (Figure 3A and B). Immunohistochemical staining of both heat shock protein (HSP) 70 and cyclase-associated protein (CAP) 2 was negative.

In May 2006, the US pattern of the nodule changed from hypoechoic to hyperechoic (Figure 2C), although the size of the nodule did not change. Constant enhanced US revealed a hypovascular nodule, and AFP, AFP L3, and PIVKA II were within normal ranges. The findings of imaging studies including contrast enhanced CT and MRI were all the same as in April 2005. A US-guided biopsy revealed well differentiated HCC of the same features as those in April 2005 with additional pseudoglandular formation and moderate cell atypia (Figure 3C and D). Immunohistochemical staining of CAP2 was over 30% positive (Figure 3E and F), although HSP70 staining was negative.

According to the classification by the International Working Party of the World Congress of Gastroenterology, hepatic nodules in patients with chronic liver diseases are subdivided into regenerative nodules (mono acinus and multi acinus), low-grade dysplastic nodules, high-grade dysplastic nodules, well-differentiated HCC, moderately-differentiated HCC, and poorly-differentiated HCC, in an ascending order of histologic grades, representing a sequence of multistep hepatocarcinogenesis[1].

It is often difficult-even for the hepatopathologist - to differentiate among regenerative nodules, precancerous lesions, and early HCC, especially from the examination of biopsy specimens. Therefore, the uncovering of an objective molecular marker that would help to standardize histological diagnosis of early HCC and to lead to appropriate treatment is eagerly anticipated. Also, the molecular mechanisms of hepatocarcinogenesis are far from clear. A molecular understanding of multistep hepatocarcinogenesis is an important step toward the identification of additional biomarkers and new therapeutic targets of a greater specificity for HCC management. Diagnosis is based on histologic analysis of liver samples for identifying cytoarchitechtural features (cell atypia, increased cellularity, increased cytoplasmic eosinophilia, fatty change, pseudoglandular formation, trabecular thickness, etc) and on information from immunocytochemical staining, such as that with HSP70[5], and CAP2[6].

Chuma et al[5] have found several up-regulated genes involved in HCC progression by comparing expression profiles among early and progressed components of seven nodule-in-nodule-type HCCs (1 HBV-positive case, 5 HCV-positive cases and 1 negative for both B and C) and their corresponding non-cancerous liver tissues, with the use of an oligonucleotide array: HSP70 (a molecular marker of early HCC) and CAP2, with up-regulated expression in a stepwise manner in multistage hepatocarcinogenesis[6].

Immunohistochemically, HSP70 is significantly overexpressed in early HCC compared with its expression in dysplastic nodules, reaching 80% in most cases of well-differentiated HCC[5].

All cases of dysplastic nodules were negative or focally positive (about 5%-10% of the lesions) for CAP2; in contrast, most cases of HCC (27 of 29 cases) were positive for CAP2, to some extent. Of the lesions, 70%-100% were positive in the progressed components, and the positivity of well-differentiated HCC ranged from 10% to 100%[6].

In our case, although CAP2 staining of the first biopsy (April 2005) was negative, that of the second (May 2006) was positive over 30%. Histopathologically, the distinct difference between the two biopsies was the pseudoglandular formation and the moderate cell atypia of the second biopsy that are specific to well-differentiated HCC.

Consequently, we made the definite diagnosis of a high-grade dysplastic nodule after the first biopsy and a well-differentiated HCC after the second biopsy.

In our case, immunohistochemical staining of HSP70 was negative in the second biopsy, whereas that of CAP2 was positive. One explanation for this discrepancy is the difference in the positivity of immunohistochemical staining of well-differentiated HCC between HSP70 (72%)[5] and CAP2 (93%)[6].

It is well accepted that HCC can in a multistep manner develop from a dysplastic nodule[7,8] into HCC. Among LC cases, the dysplastic nodule is usually HCV-related, rarely HBV-related, and has not been reported as alcohol-related. Similarly, multistep hepatocarcinogenesis from a dysplastic nodule to well-differentiated HCC is usually HCV-related, rarely HBV-related, and has not been reported as alcohol-related[4].

In April 2001, no nodule was detected; in April 2005, a 10 mm hypoechoic nodule with the background of alcohol-related LC appeared in S7. Imaging studies by contrast enhanced US, CT, MRI, CTA, and CTAP revealed a hypovascular nodule compatible with a dysplastic nodule or well-differentiated HCC. The histopathological findings revealed a high-grade dysplastic nodule. In May 2006, the US pattern of the nodule changed from hypoechoic to hyperechoic without any change in size, and the imaging findings other than US were all the same as those in April 2005. Tumor markers such as AFP, AFP L3 and PIVKA II were within normal ranges. The histopathological findings of the hyperechoic nodule revealed well-differentiated HCC. Alcohol abuse in some cases induces hyperplastic nodules that are usually associated with hypervascularity[9-11] and that are often misdiagnosed as HCC from imaging studies, as are dysplastic nodules from histopathological findings. Hyperplastic nodules do not, however, transform to HCC and often disappear subsequent to discontinued alcohol intake. The dysplastic nodule in our case is, in this respect, different from the hyperplastic nodule associated with hypervascularity. The clinical course of the patient showed multistep hepatocarcinogenesis from a dysplastic nodule to well-differentiated HCC within one year with the background of alcohol-related LC. The mechanism by which alcohol causes HCC is not known, but has been hypothesized to include oxidative stress, changes in retinoic acid metabolism and DNA methylation, decreased immune surveillance and genetic susceptibility[4]. The former three factors are common in patients with alcohol abuse. The latter two factors are specific to patients with individual differences of alcohol intake. In this case immunological examinations including immunoglobulin, the percentage of B cells and T cells, CD4/CD8 ratio, and NK cell activity were within almost normal limits. Therefore, one explanation for the transformation from a dysplastic nodule to an HCC may be genetic susceptibility that was not examined at the time.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of multistep hepatocarcinogenesis from a dysplastic nodule to a well-differentiated HCC in alcohol-related LC.

Further study is needed to clarify the objective criteria for the definite diagnosis of dysplastic nodules and well-differentiated HCC, and the precise mechanism of hepatocarcinogenesis in alcohol-related LC.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Zhu LH E- Editor Chin GJ

| 1. | Terminology of nodular hepatocellular lesions. Hepatology. 1995;22:983-993. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 836] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 667] [Article Influence: 47.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Takayama T, Makuuchi M, Hirohashi S, Sakamoto M, Okazaki N, Takayasu K, Kosuge T, Motoo Y, Yamazaki S, Hasegawa H. Malignant transformation of adenomatous hyperplasia to hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 1990;336:1150-1153. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 319] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 281] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ikai I, Itai Y, Okita K, Omata M, Kojiro M, Kobayashi K, Nakanuma Y, Futagawa S, Makuuchi M, Yamaoka Y. Report of the 15th follow-up survey of primary liver cancer. Hepatol Res. 2004;28:21-29. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 127] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Morgan TR, Mandayam S, Jamal MM. Alcohol and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S87-S96. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Chuma M, Sakamoto M, Yamazaki K, Ohta T, Ohki M, Asaka M, Hirohashi S. Expression profiling in multistage hepatocarcinogenesis: identification of HSP70 as a molecular marker of early hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2003;37:198-207. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 236] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Shibata R, Mori T, Du W, Chuma M, Gotoh M, Shimazu M, Ueda M, Hirohashi S, Sakamoto M. Overexpression of cyclase-associated protein 2 in multistage hepatocarcinogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5363-5368. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sakamoto M, Hirohashi S, Shimosato Y. Early stages of multistep hepatocarcinogenesis: adenomatous hyperplasia and early hepatocellular carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 1991;22:172-178. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 400] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 363] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kojiro M, Shigetaka S, Nakashima O. Pathomorphologic characteristics of early hepatocellular carcinoma. In: Okuda K, Tobe T, Kitagawa T, editors. Early detection and treatment of liver cancer. Gann Monogr Cancer Res. 1991;38:29-37. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Nakashima O, Watanabe J, Tanaka M, Fukukura Y, Kojiro M, Kurohiji T, Saitsu H, Adachi A, Nabeshima M, Miura K. Clinicopathologic study of hyperplastic nodules in patient with chronic alcoholic liver disease. Kanzo. 1996;37:704-713. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kita R, Osaki Y, Maruo T, Kimura T, Kokuryu H, Takamatsu S, Tomono N, Shimizu T. A case of severe alcoholic liver cirrhosis with multiple hyperplastic nodules. Kanzo. 2001;42:203-209. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Nagasue N, Akamizu H, Yukaya H, Yuuki I. Hepatocellular pseudotumor in the cirrhotic liver. Report of three cases. Cancer. 1984;54:2487-2494. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |