Published online Oct 14, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i38.5158

Revised: July 28, 2007

Accepted: August 6, 2007

Published online: October 14, 2007

We describe the clinical, imaging and cytopathological features of solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas (SPTP) diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided (EUS-guided) fine-needle aspiration (FNA). A 17-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with complaints of an unexplained episodic abdominal pain for 2 mo and a short history of hypertension in the endocrinology clinic. Clinical laboratory examinations revealed polycystic ovary syndrome, splenomegaly and low serum amylase and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels. Computed tomography (CT) analysis revealed a mass of the pancreatic tail with solid and cystic consistency. EUS confirmed the mass, both in body and tail of the pancreas, with distinct borders, which caused dilation of the peripheral part of the pancreatic duct (major diameter 3.7 mm). The patient underwent EUS-FNA. EUS-FNA cytology specimens consisted of single cells and aggregates of uniform malignant cells, forming microadenoid structures, branching, papillary clusters with delicate fibrovascular cores and nuclear overlapping. Naked capillaries were also seen. The nuclei of malignant cells were round or oval, eccentric with fine granular chromatin, small nucleoli and nuclear grooves in some of them. The malignant cells were periodic acid Schiff (PAS)-Alcian blue (+) and immunocytochemically they were vimentin (+), CA 19.9 (+), synaptophysin (+), chromogranin (-), neuro-specific enolase (-), a1-antitrypsin and a1-antichymotrypsin focal positive. Cytologic findings were strongly suggestive of SPTP. Biopsy confirmed the above cytologic diagnosis. EUS-guided FNA diagnosis of SPTP is accurate. EUS findings, cytomorphologic features and immunostains of cell block help distinguish SPTP from pancreatic endocrine tumors, acinar cell carcinoma and papillary mucinous carcinoma.

- Citation: Salla C, Chatzipantelis P, Konstantinou P, Karoumpalis I, Pantazopoulou A, Dappola V. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology diagnosis of solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: A case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(38): 5158-5163

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i38/5158.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i38.5158

Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas (SPTP) is a rare neoplasm with a reported frequency of between 0.17% and 2.7% of all nonendocrine tumors of the pancreas[1], and 6.5% of all pancreatic tumors and tumor-like lesions resected in one large institute[2]. This tumor seems to preferentially occur in young females with a reported mean age of 25 to 30 years, ranging 11-73 years[2,3]. In the elderly population it has been suggested that SPTP tend to be malignant[4,5]. It was first described by Frantz in 1959[6]. Multiple descriptive names have been used for this tumor, including papillary epithelial neoplasm, papillary/cystic neoplasm, solid-and-papillary epithelial neoplasm, papillary-cystic carcinoma, solid-and papillary neoplasm, low-grade papillary neoplasm, and the Frantz tumor[7]. The WHO pancreatic tumor working group recently recommended the use of the term solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm[8], a term that has been widely used and accepted by pathologists and clinicians in daily practice[9,10].

Almost 610 SPTPs, including more than 57 diagnosed by percutaneous fine-needle aspiration (FNA), have been reported since the initial description in 1959[6]. In recent years, image-guided FNA has been increasingly performed for pancreatic lesions. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided FNA can have an important role and provide an accurate preoperative diagnosis particularly when the EUS findings of the mass are inconclusive. EUS-guided FNA can differentiate SPTP from other pancreatic neoplasms of similar radiologic and cytologic appearance but with different biologic behaviour and treatment, such as pancreatic endocrine tumors, acinar cell carcinoma, and papillary mucinous carcinoma[11-17]. The cytomorphology of this tumor is highly characteristic, with features that are distinctive from those of other cystic and solid tumors of the pancreas. It is important that this tumor is accurately diagnosed because management protocols differ from other tumor types originating in the pancreas.

In this paper, we describe the clinical, imaging, cytomorphologic features and differential diagnosis of a new case of SPTP diagnosed by EUS-guided FNA with a review of the literature.

A 17-year-old woman was admitted with complaints of an unexplained episodic pain for 2 mo and a short history of hypertension in the endocrinology clinic of our hospital (Athens General Hospital, Greece). Clinical laboratory examinations revealed polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOs), splenomegaly and low serum amylase and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels. CT-scan revealed a mass of the pancreatic tail with solid and cystic consistency.

EUS-guided FNA was performed using 22-gauge needles via a transgastric approach. Smears were made at the bedside in the endoscopy suite. The aspirated material was smeared onto glass slides, air-dried, and immediately stained with rapid Hemo-color stain for specimen adequacy assessment and preliminary diagnostic interpretation. Other smears also were fixed immediately in 95% alcohol for subsequent Papanicolaou staining. Additional aspirated material was fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, and processed for routine histologic examination using standard techniques. Staining with periodic acid Schiff (PAS) and Alcian-blue (AB) stains was performed. Immunohistochemical stains for vimentin (Dako; 1:100), neuron-specific enolase (NSE) (Dako; 1:100), synaptophysin (NovoCastra, Newcastle UK), chromogranin (Dako; 1:800), CA 19.9 (Dako), a1-antitrypsin (Dako; 1:3200), a1-antichymotrypsin (Dako; 1:800), were also performed. Avidin-biotin peroxidase complex technique was used.

Smears and cell block sections were examined with an emphasis on the evaluation of cytomorphologic features and immunohistochemical results.

EUS confirmed a mass, both in body and tail of the pancreas, with distinct borders, which caused dilation of the peripheral part of the pancreatic duct [major diameter (m.d.) 3.7 mm]. More specifically the tumor mass was solid and cystic, hypoechoic and heterogenous with a size measuring 65.4 mm × 54.2 mm (Figure 1). The EUS differential diagnosis included serous cystadenoma, mucinous cystadenoma, mucinous cystadenocarcinoma, adenocarcinoma with cystic degeneration, endocrine tumor and SPTP.

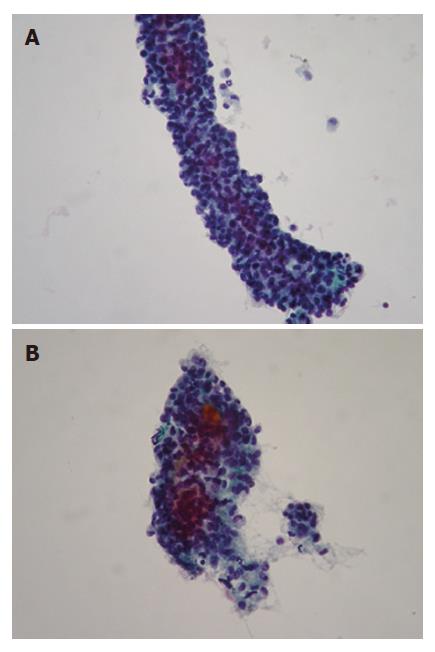

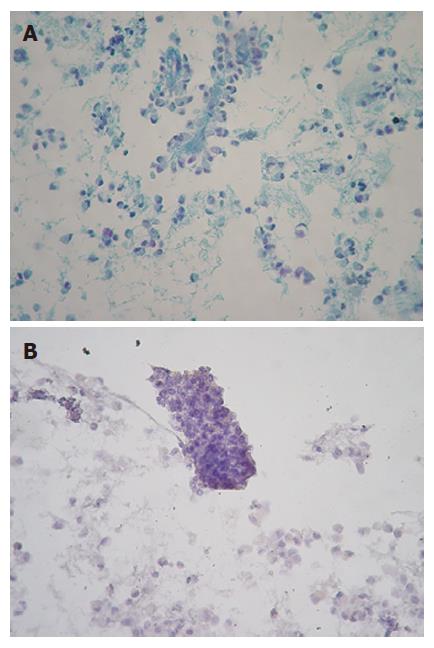

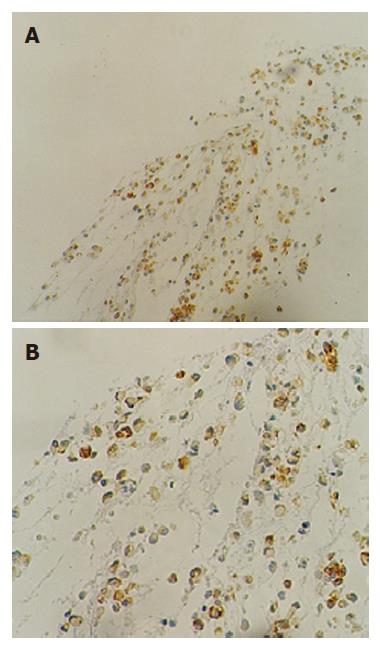

Smears were hypercellular and characteristically showed branching papillary arrangements composed of delicate fibrovascular cores and microadenoid structures with attached monotonous cuboidal neoplastic cells (Figure 2A- B). The nuclei of malignant cells were round or oval, eccentric with finely granular chromatin, small nucleoli and in some of them nuclear grooves. Cytoplasm was granular or finely vacuolated with wispy borders. No mitotic activity or significant atypia was observed. The architectural features were more evident in the cell block sections. Histochemically, tumor cells revealed PAS Alcian-blue (+) (Figure 3A-B). Immunostains performed on the cell block yielded vimentin positivity (Figure 4A), CA 19.9 positivity (Figure 4B), synaptophysin, a1-antitrypsin and a1-antichymotryspin focal positivity whereas NSE and chromogranin were negative. These findings were strongly suggestive of SPTP.

Solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm is an exceedingly rare pancreatic tumor with a reported frequency of less than 1% of all pancreatic diseases. Most of these reports are in the form of small case series with only few reports with greater than 50 cases identified in the literature.

It predominantely occurs in adolescent girls and young women with a reported frequency of 87% to 90% (mean age of 25 to 35 years)[2,3]. Such a striking predilection of SPTP occurring in women has suggested a hormonal influence on the pathogenesis of this tumor[18,19]. Cases occurring at the first decade of life are rare and less than 10% of SPTP cases have been reported in patients older than 40 years[2,20]. Occurrence of SPTP in men is rare, accounting for 7% of cases[21].

Clinically, SPTP may present as an abdominal mass with discomfort or pain, or it may be an incidental finding in work up for unrelated conditions. These tumors are generally large with a mean diameter of 10.3 cm and approximately 72% arise in the body and tail of the pancreas and less frequently in the head[2]. Unusual presentations of SPTP include multicentricity[22,23], occurrence in extrapancreatic sites such as mesocolon[24], retroperitoneum[25], omentum[26], liver[27] and duodenum[28]. In our case, the sex (female), age (17 years old) and tumor localization (body and tail of the pancreas) were typical of SPTP.

In most patients, the tumor follows an indolent clinical course and complete resection is often curative[20,29]. Up to 15% of cases have shown aggressive behaviour consisting of extension into adjacent blood vessels and organs, local recurrence and distant metastasis[20,28,30,31]. However, even metastatic SPTPs are growing slowly and have excellent prognosis. Only one death, due to metastatic spread of SPTP has been reported[32]. Also, spontaneously regressing tumors have been reported[33].

Benign-appearing SPTP might contrast with cellular anaplasia present in the metastatic deposits[34]. Thus, there are no histological features that can predict aggressive clinical behaviour. Proposed pathologic features related to aggressive behaviour or metastatic potential include diffuse growth pattern, venous invasion, nuclear pleomorphism, mitotic rate, necrosis and areas of dedifferentiation[35]. Most SPTPs display diploid DNA content[1]. However, DNA aneuploidy is more prominent in malignant SPTPs[34,36]. Chromosomal abnormalities, including double loss of X chromosomes and trisomy for chromosome 3, and unbalanced translocation between chromosomes 13 and 17 have been found in SPTP associated with aggressive behaviour and might be indicators of possible metastatic potential[37,38]. Thus, since the malignant potential of SPTP is difficult to determine, this tumor is considered a low malignant or borderline malignant potential.

The histogenesis of SPTP has been, and to date remains, elusive. Multiple theories have been proposed, including origin from small duct epithelium, derivation from acinar cells, endocrine pancreas, totipotential stem cells, or primitive cells capable of differentiating exocrine and endocrine[4,39-41], along with genital ridge-related cells that are incorporated in the pancreas during early embryogenesis[42]. Another recent report showed that SPTP is positive for melanocytic markers (S-100 protein, human melanoma black 45 (HMB45) and melanoma antigen recognized by T-cells 1 (MART-1) by immunohistochemistry and demonstrated the presence of premelanosomes and melanosome granules in the tumor cells by transmission electron microscopy, suggesting that this tumor may be of neural crest origin[43]. Also, predilection in young women suggests that sex hormones play a role in the histogenesis or progression of this tumor. However, the ER and PR expression are not consistent in the literature. Using a binding essay, Ladanyi et al[18] demonstrated the expression of ER in SPTP and proposed that this tumor is hormone sensitive.

Diagnosis of SPTP is important for the clinical management of patients with this tumor. Diagnostic modalities including CT and magnetic resonance imaging can only suggest a diagnosis of SPTP. CT findings include an encapsulated lesion with well-defined borders and variable central areas with cystic degeneration, necrosis, or hemorrhage. Calcifications may occasionally be seen. Magnetic resonance imaging is helpful for identifying the characteristic internal signal intensities of blood products, which help distinguish this tumor from other cystic pancreatic tumors[44].

In recent years, advances in technology have permitted the performance of fine-needle aspiration biopsy under EUS guidance[45,46]. The overall accuracy of EUS is superior to CT scan and magnetic resonance imaging for detecting pancreatic lesions. It has been shown that EUS alone (94%) is more sensitive than CT scan (69%) and magnetic resonance imaging (83%) for detecting lesions, especially when they are smaller than 3.0 cm[47]. EUS permits a better evaluation of SPTPs, but the findings also are not specific. A small SPTP, often a monocystic tumor most frequent in males, might have the EUS appearance of a solid endocrine neoplasm, and it might be difficult to distinguish between the two[48].

An accurate preoperative diagnosis is highly desirable, since local surgical excision is usually curative and this is possible by EUS-guided FNA cytology. Bondeson et al[49] were the first to correctly diagnose SPTP by preoperative FNA.

Since then, to our knowledge, cytologic findings of percutaneous FNA-diagnosed SPTP have been described in 57 cases[9,21,22,31,37,49-53]. However, only few cases have been diagnosed by EUS-guided FNA[9,54]. FNA cytomorphologic features are highly characteristic and distinct from those of other cystic or solid tumors of the pancreas. On aspirated matrials, the most frequent features are the presence of marked cellularity with pseudopapillary fragments composed of fibrovascular stalks lined with one to several layers of tumor cells intermingled with discohesive neoplastic cells[1,21,22,49,51]. Careful evaluation of smears for mitotic activity is recommended, since this parameter has recently been considered one predictive criterion for biologic aggressiveness[55]. Inter or intracellular pink hyaline globules, mucus-like globules, as in our case, surrounded by stromal cells and cellular debris are also frequent features.

Immunohistochemically, most SPTPs are immunoreactive for vimentin (vim), a1-antitrypsin (AAT), a1-antichymotrypsin (AACT)[56], occassionally positive for neuron-specific enolase and synaptophysin (syn)[9], and nonreactive for S-100, CA 19.9 and chromogranin A. In our case, SPTP was vim (+), AAT (+), AACT (+), CA 19.9 (+) and syn (+). The above-mentioned cytologic and immunohistochemical features are strongly suggestive of SPTP.

The differential diagnosis of SPTP includes pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, acinar-cell carcinoma, papillary mucinous carcinoma and intraductal papillary mucinous tumor. Pancreatic endocrine tumors predominantly occur in older patients and can be associated with a variety of clinical syndromes. These tumors share some cytological features with SPTP. The presence of rosettes without papillary structures and typical “salt and pepper” chromatin indicates a pancreatic endocrine tumor[20,16]. Additionally, these tumors express neuroendocrine markers such as chromogranin, neuron-specific enolase, and synaptophysin which are usually nonreactive in cases of SPTP. Acinar-cell carcinoma occurring in a wide range of age, is more commonly observed in males, and shows no predilection for head, body or tail location in the pancreas. Aspirates are cellular and composed only of acinar neoplastic cells containing enlarged nuclei with irregular membranes and distinct nucleoli. Patients with papillary mucinous carcinoma often have a single, large unilocular cystic mass and the neoplastic cells are columnar with cytoplasmic vacuoles, variable nuclear anaplasia, prominent nucleoli and mucinous background that should not be mistaken for the myxoid stroma[22,57]. Also, the thick, glistening and viscid mucus almost always present in intraductal papillary mucinous tumor is an important feature that distinguishes this neoplasm from SPTP[58].

In conclusion, we believe that EUS-FNA provides an excellent cellular yield and an overall sensitivity for the diagnosis of SPTP. Clinical correlation, radiological findings and cytomorphologic features from EUS-guided FNA achieve the accurate diagnosis of SPTP.

S- Editor Zhu LH L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Li JL

| 1. | Pettinato G, Manivel JC, Ravetto C, Terracciano LM, Gould EW, di Tuoro A, Jaszcz W, Albores-Saavedra J. Papillary cystic tumor of the pancreas. A clinicopathologic study of 20 cases with cytologic, immunohistochemical, ultrastructural, and flow cytometric observations, and a review of the literature. Am J Clin Pathol. 1992;98:478-488. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Kosmahl M, Pauser U, Peters K, Sipos B, Lüttges J, Kremer B, Klöppel G. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas and tumor-like lesions with cystic features: a review of 418 cases and a classification proposal. Virchows Arch. 2004;445:168-178. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Brázdil J, Hermanová M, Kren L, Kala Z, Neumann C, Růzicka M, Nenutil R. [Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: 5 case reports]. Rozhl Chir. 2004;83:73-78. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Matsunou H, Konishi F. Papillary-cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. A clinicopathologic study concerning the tumor aging and malignancy of nine cases. Cancer. 1990;65:283-291. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Takahashi H, Hashimoto K, Hayakawa H, Kusakawa M, Okamura K, Kosaka A, Mizumoto R, Katsuta K. Solid cystic tumor of the pancreas in elderly men: report of a case. Surg Today. 1999;29:1264-1267. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Frantz VK. Tumor of the pancreas. Washington DC: US Armed Forces Institute of Pathology 1959; 32-33. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Zhou H, Cheng W, Lam KY, Chan GC, Khong PL, Tam PK. Solid-cystic papillary tumor of the pancreas in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2001;17:614-620. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Klöppel G, Luttges J, Klimstra D. Solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm. WHO Classification of Tumors Pathology and Genetics, Tumor of the Digestive System. Lyon, France: IARC 2000; 246-248. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Bardales RH, Centeno B, Mallery JS, Lai R, Pochapin M, Guiter G, Stanley MW. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology diagnosis of solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a rare neoplasm of elusive origin but characteristic cytomorphologic features. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:654-662. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Lack EE. Solid-pseudopapillary neoplasma. Pathology of the Pancreas, Gallbladder, Extrahepatic Biliary Tract, and Ampullary Region. New York: Oxford University Press 2003; 281-290. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Koito K, Namieno T, Nagakawa T, Shyonai T, Hirokawa N, Morita K. Solitary cystic tumor of the pancreas: EUS-pathologic correlation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:268-276. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Brugge WR. Role of endoscopic ultrasound in the diagnosis of cystic lesions of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2001;1:637-640. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Das DK, Bhambhani S, Kumar N, Chachra KL, Prakash S, Gupta RK, Tripathi RP. Ultrasound guided percutaneous fine needle aspiration cytology of pancreas: a review of 61 cases. Trop Gastroenterol. 1995;16:101-109. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Nadler EP, Novikov A, Landzberg BR, Pochapin MB, Centeno B, Fahey TJ, Spigland N. The use of endoscopic ultrasound in the diagnosis of solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:1370-1373. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Centeno BA. Fine needle aspiration biopsy of the pancreas. Clin Lab Med. 1998;18:401-427, v-vi. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Collins BT, Saeed ZA. Fine needle aspiration biopsy of pancreatic endocrine neoplasms by endoscopic ultrasonographic guidance. Acta Cytol. 2001;45:905-907. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Rampy BA, Waxman I, Xiao SY, Logroño R. Serous cystadenoma of the pancreas with papillary features: a diagnostic pitfall on fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:1591-1594. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Ladanyi M, Mulay S, Arseneau J, Bettez P. Estrogen and progesterone receptor determination in the papillary cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. With immunohistochemical and ultrastructural observations. Cancer. 1987;60:1604-1611. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Wrba F, Chott A, Ludvik B, Schratter M, Spona J, Reiner A, Schernthaner G, Krisch K. Solid and cystic tumour of the pancreas; a hormonal-dependent neoplasm? Histopathology. 1988;12:338-340. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Lam KY, Lo CY, Fan ST. Pancreatic solid-cystic-papillary tumor: clinicopathologic features in eight patients from Hong Kong and review of the literature. World J Surg. 1999;23:1045-1050. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Pettinato G, Di Vizio D, Manivel JC, Pambuccian SE, Somma P, Insabato L. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a neoplasm with distinct and highly characteristic cytological features. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;27:325-334. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Young NA, Villani MA, Khoury P, Naryshkin S. Differential diagnosis of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas by fine-needle aspiration. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1991;115:571-577. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Orlando CA, Bowman RL, Loose JH. Multicentric papillary-cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1991;115:958-960. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Tornóczky T, Kálmán E, Jáksó P, Méhes G, Pajor L, Kajtár GG, Battyány I, Davidovics S, Sohail M, Krausz T. Solid and papillary epithelial neoplasm arising in heterotopic pancreatic tissue of the mesocolon. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:241-245. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Klöppel G, Maurer R, Hofmann E, Lüthold K, Oscarson J, Forsby N, Ihse I, Ljungberg O, Heitz PU. Solid-cystic (papillary-cystic) tumours within and outside the pancreas in men: report of two patients. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1991;418:179-183. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Fukunaga M. Pseudopapillary solid cystic tumor arising from an extrapancreatic site. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:1368-1371. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Kim YI, Kim ST, Lee GK, Choi BI. Papillary cystic tumor of the liver. A case report with ultrastructural observation. Cancer. 1990;65:2740-2746. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Pasquiou C, Scoazec JY, Gentil-Perret A, Taniere P, Ranchere-Vince D, Partensky C, Barth X, Valette PJ, Bailly C, Mosnier JF. [Solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas. Pathology report of 13 cases]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1999;23:207-214. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Mao C, Guvendi M, Domenico DR, Kim K, Thomford NR, Howard JM. Papillary cystic and solid tumors of the pancreas: a pancreatic embryonic tumor? Studies of three cases and cumulative review of the world's literature. Surgery. 1995;118:821-828. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | González-Cámpora R, Rios Martin JJ, Villar Rodriguez JL, Otal Salaverri C, Hevia Vazquez A, Valladolid JM, Portillo M, Galera Davidson H. Papillary cystic neoplasm of the pancreas with liver metastasis coexisting with thyroid papillary carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995;119:268-273. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Compagno J, Oertel JE, Krezmar M. Solid and papillary epithelial neoplasm of the pancreas, probably of small duct origin: a clinicopathologic study of 52 cases. Lab Invest. 1979;40:248-249. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Buetow PC, Buck JL, Pantongrag-Brown L, Beck KG, Ros PR, Adair CF. Solid and papillary epithelial neoplasm of the pancreas: imaging-pathologic correlation on 56 cases. Radiology. 1996;199:707-711. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Hachiya M, Hachiya Y, Mitsui K, Tsukimoto I, Watanabe K, Fujisawa T. Solid, cystic and vanishing tumors of the pancreas. Clin Imaging. 2003;27:106-108. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Cappellari JO, Geisinger KR, Albertson DA, Wolfman NT, Kute TE. Malignant papillary cystic tumor of the pancreas. Cancer. 1990;66:193-198. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Washington K. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: challenges presented by an unusual pancreatic neoplasm. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:3-4. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Kamei K, Funabiki T, Ochiai M, Amano H, Marugami Y, Kasahara M, Sakamoto T. Some considerations on the biology of pancreatic serous cystadenoma. Int J Pancreatol. 1992;11:97-104. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 37. | Grant LD, Lauwers GY, Meloni AM, Stone JF, Betz JL, Vogel S, Sandberg AA. Unbalanced chromosomal translocation, der(17)t(13; 17)(q14; p11) in a solid and cystic papillary epithelial neoplasm of the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:339-345. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 38. | Matsubara K, Nigami H, Harigaya H, Baba K. Chromosome abnormality in solid and cystic tumor of the pancreas. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1219-1221. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 39. | Stömmer P, Kraus J, Stolte M, Giedl J. Solid and cystic pancreatic tumors. Clinical, histochemical, and electron microscopic features in ten cases. Cancer. 1991;67:1635-1641. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 40. | Yagihashi S, Sato I, Kaimori M, Matsumoto J, Nagai K. Papillary and cystic tumor of the pancreas. Two cases indistinguishable from islet cell tumor. Cancer. 1988;61:1241-1247. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 41. | Miettinen M, Partanen S, Fräki O, Kivilaakso E. Papillary cystic tumor of the pancreas. An analysis of cellular differentiation by electron microscopy and immunohistochemistry. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11:855-865. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 42. | Kosmahl M, Seada LS, Jänig U, Harms D, Klöppel G. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: its origin revisited. Virchows Arch. 2000;436:473-480. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 43. | Chen C, Jing W, Gulati P, Vargas H, French SW. Melanocytic differentiation in a solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:579-583. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 44. | Cantisani V, Mortele KJ, Levy A, Glickman JN, Ricci P, Passariello R, Ros PR, Silverman SG. MR imaging features of solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas in adult and pediatric patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:395-401. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 45. | Wiersema MJ, Hawes RH, Tao LC, Wiersema LM, Kopecky KK, Rex DK, Kumar S, Lehman GA. Endoscopic ultrasonography as an adjunct to fine needle aspiration cytology of the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:35-39. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 46. | Vilmann P, Jacobsen GK, Henriksen FW, Hancke S. Endoscopic ultrasonography with guided fine needle aspiration biopsy in pancreatic disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:172-173. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 47. | Müller MF, Meyenberger C, Bertschinger P, Schaer R, Marincek B. Pancreatic tumors: evaluation with endoscopic US, CT, and MR imaging. Radiology. 1994;190:745-751. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 48. | Uchimi K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Kimura K, Matsunaga A, Yuki T, Nomura M, Sato T, Ishida K. Solid cystic tumor of the pancreas: report of six cases and a review of the Japanese literature. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:972-980. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 49. | Bondeson L, Bondeson AG, Genell S, Lindholm K, Thorstenson S. Aspiration cytology of a rare solid and papillary epithelial neoplasm of the pancreas. Light and electron microscopic study of a case. Acta Cytol. 1984;28:605-609. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 50. | Pelosi G, Iannucci A, Zamboni G, Bresaola E, Iacono C, Serio G. Solid and cystic papillary neoplasm of the pancreas: a clinico-cytopathologic and immunocytochemical study of five new cases diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology and a review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 1995;13:233-246. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 51. | Katz LB, Ehya H. Aspiration cytology of papillary cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;94:328-333. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 52. | Granter SR, DiNisco S, Granados R. Cytologic diagnosis of papillary cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. Diagn Cytopathol. 1995;12:313-319. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 53. | Bhanot P, Nealon WH, Walser EM, Bhutani MS, Tang WW, Logroño R. Clinical, imaging, and cytopathological features of solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a clinicopathologic study of three cases and review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2005;33:421-428. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 54. | Mergener K, Detweiler SE, Traverso LW. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: diagnosis by EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration. Endoscopy. 2003;35:1083-1084. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 55. | Nishihara K, Nagoshi M, Tsuneyoshi M, Yamaguchi K, Hayashi I. Papillary cystic tumors of the pancreas. Assessment of their malignant potential. Cancer. 1993;71:82-92. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 56. | Liu X, Rauch TM, Siegal GP, Jhala N. Solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: Three cases with a literature review. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2006;14:445-453. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 57. | Naresh KN, Borges AM, Chinoy RF, Soman CS, Krishnamurthy SC. Solid and papillary epithelial neoplasm of the pancreas. Diagnosis by fine needle aspiration cytology in four cases. Acta Cytol. 1995;39:489-493. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 58. | Stelow EB, Stanley MW, Bardales RH, Mallery S, Lai R, Linzie BM, Pambuccian SE. Intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. The findings and limitations of cytologic samples obtained by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;120:398-404. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |