Published online Jul 14, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i26.3554

Revised: April 3, 2007

Accepted: April 26, 2007

Published online: July 14, 2007

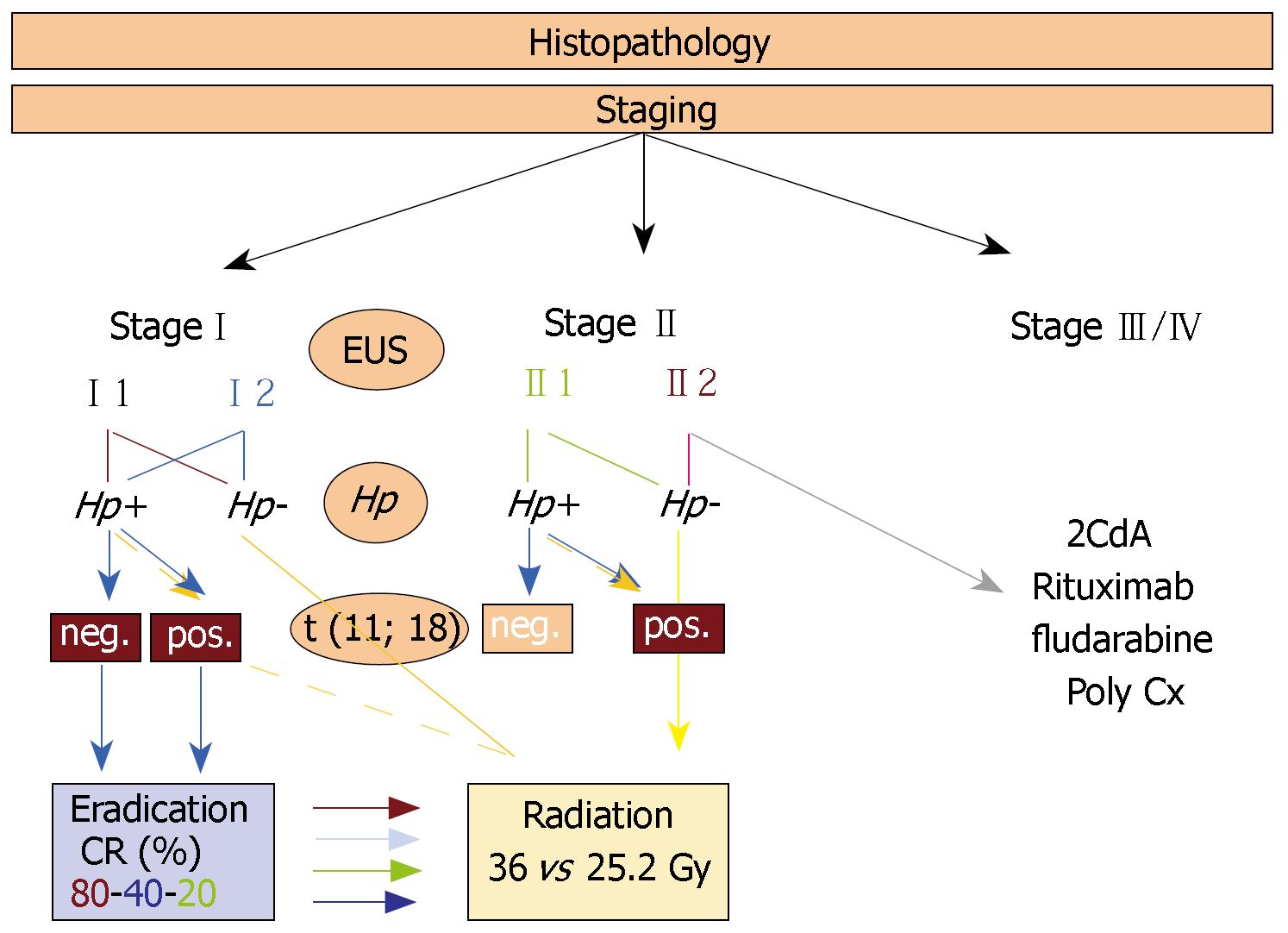

Gastric mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma has recently been incorporated into the World Health Organization (WHO) lymphoma classification, termed as extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT-type. In about 90% of cases this lymphoma is associated with H pylori infection which has been clearly shown to play a causative role in lymphomagenesis. Although much knowledge has been gained in defining the clinical features, natural history, pathology, and molecular genetics of the disease in the last decade, the optimal treatment approach for gastric MALT lymphomas, especially locally advanced cases, is still evolving. In this review we focus on data for the therapeutic, stage dependent management of gastric MALT lymphoma. Hence, the role of eradication therapy, surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy is critically analyzed. Based on these data, we suggest a therapeutic algorithm that might help to better stratify patients for optimal treatment success.

- Citation: Morgner A, Schmelz R, Thiede C, Stolte M, Miehlke S. Therapy of gastric mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(26): 3554-3566

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i26/3554.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i26.3554

Primary gastric lymphomas are of extranodal non-Hodgkin type (NHL). Even though they represent only 2%-3% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and 7% of all gastric tumours, they are nevertheless the most common extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma manifestation, and most of them are of B-cell origin[1]. According to the current World Health Organisation (WHO) classification, 40% of primary gastric lymphomas are termed as indolent (former low grade), and 60% as aggressive (high grade) type[2]. The grading of gastric lymphomas is very important in both the prognosis and treatment of the disease. Indolent gastric lymphomas include mantle cell lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, follicular lymphoma, and gastric mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. The latter has also been termed low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma, gastric marginal B-cell lymphoma, and extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT type[3]. Gastric MALT lymphoma represents the vast majority of the three different types of marginal-zone B-cell lymphomas (MZBCL) corresponding to the Revised European American Lymphoma classification (REAL)[1,2]. The observation that the histology of certain extranodal NHLs was related to MALT rather than that of peripheral lymph nodes was first made by Isaacson and Wright in 1983[4]. In about 90% of cases, MZBCL of MALT type is associated with H pylori infection which has been clearly shown to play a causative role in the pathogenesis of gastric MALT lymphoma[5].

Primary gastric aggressive-type lymphomas are classified as diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL). They contain an indolent MALT component in about one third of cases. This lesion likely represents progression of disease from indolent to aggressive lymphomas[6,7]. The remaining two thirds of high-grade lymphomas have no detectable low-grade MALT component. However, it is controversial whether these tumours arose from indolent lesions with subsequent obliteration of the low-grade component in any case or whether these tumours may be considered better as de novo extranodal diffuse large B-cell lymphomas rather than transformed MALT lymphomas. For both, an association with H pylori has been described as it induces acquired MALT in the gastric mucosa, promotes malignant transformation of reactive B-cells and induces genotoxic effects via neutrophil released ROS, causing a wide range of genetic abnormalities[8]. Hence, newly described translocations such as t (11; 18) (q21; q21) or t (1; 14) (p22; q32) may play a key role in patients stratification for the most effective therapeutic approach in the future.

As simple as the initial diagnostic, staging and therapeutic approach to patients with gastric MALT lymphoma may seem, proper patient management is nevertheless crucial. Furthermore, there is still controversy regarding the most effective treatment strategy, especially in patients who do no respond to eradication therapy. This review will focus on treatment strategies for gastric MALT lymphoma under consideration of H pylori infection, molecular genetics, and the trend to effective conservative treatment modalities.

The first evidence of H pylori infection being associated with a gastric immune response was found in 1988[9]. It was followed by the discovery of coherence between H pylori infection and gastric MZBCL of MALT-type in 1991[5]. The latter study showed that the presence of H pylori increases the risk of gastric MALT lymphoma, because the vast majority of patients with gastric MALT lymphoma were infected with H pylori[8]. Moreover, case control studies have shown an association between previous H pylori infection and the development of primary gastric lymphoma[10]. Direct evidence confirming the importance of H pylori in the pathogenesis of gastric MALT-lymphoma was obtained from studies that detected the lymphoma B-cell clone in biopsy specimens of patients with chronic gastritis only that preceded the development of lymphoma. H pylori infection was found to cause an immunological response, leading to chronic gastritis with formation of lymphoid follicles within the stomach[11]. These lymphoid follicles resemble nodal tissues found throughout the body and are composed of reactive T cells and activated plasma cells and B cells. Moreover, the bacterial infection provokes a neutrophilic response, which causes the release of oxygen free radicals. These reactive species may promote the acquisition of genetic abnormalities and malignant transformation of reactive B cells. The B cells are responsible for initiating a clonal expansion of centrocyte-like cells that form the basic histology of MALT lymphoma[8]. In addition, a series of in vitro studies showed that lymphoma growth could be stimulated in culture by H pylori strain-specific T cells when crude lymphoma cultures were exposed to the organism[12]. Finally, Wotherspoon et al[13] in 1993, and subsequently several other groups[14-25], showed that eradication of H pylori with antibiotics alone resulted in regression of gastric MALT lymphoma in 60%-90% of cases.

A number of genetic and epigenetic abnormalities have been described in MALT lymphoma at various sites. These abnormalities include the trisomy of chromosomes 3, 12 and 18 and a number of translocations, which are mutually exclusive for low grade MALT lymphomas, including t (11; 18) (q21; q21), t (14; 18) (q32; q21), t (1; 14) (p22; q32), and t (3; 14) (p14; q32)[26], the latter 2 translocations occur more frequently in non-gastrointestinal MALT lymphomas[26,27]. Trisomies 3 and/or 18 are present as the sole abnormality in 22% of cases, but in many others, is frequently associated with IGH-MALT1, IGH-BCL10 and IgH-FOXP1 but only rarely with API2-MALT1. Other detected abnormalities of unknown significance are aberrations of the C-MYC oncogene, FAS gene mutations, hypermethylation of p15 and p16 genes, microsatellite instability, and BCL-2 overexpression[28-32].

The translocation t (11; 18) (q21; 21) is the most common chromosomal abnormality associated with MALT lymphomas[33], occurring in 20%-60% of cases[34-37]. This translocation fuses the member of the inhibitors of apoptosis (IAO) family API2 (also known as BIRC3, cIAP2, HIOP1, MIHC) on chromosome 11 with the MALT1 (MALT lymphoma-associated translocation) gene on chromosome 18, resulting in the expression of a chimeric protein product[38,39]. This fusion product API2-MALT1 of t (11; 18) appears to be capable of increasing the translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus[40,41]. NF-κB transactivates genes such as cytokines and growth factors that are important for cellular activation, proliferation, and survival thus contributing to lymphoma development[42]. The clinical significance of this genetic aberration was suggested by a study of 18 patients with early gastric MALT lymphoma who responded to eradication therapy and in whom t (11; 18) was not found[43]. On the other hand, patients not responding to eradication therapy were mostly t (11; 18) positive[36,44]. To date this translocation has shown to be predictive for advanced stage of low grade gastric MALT lymphoma and only occasional response to H pylori eradication treatment[37,45].

The translocation t (1; 14) (p22; q32) is found in less than 5% of MALT lymphomas[46]. As a result of this translocation, the entire coding region of the BCL10 gene on chromosome 1 is relocated to chromosome 14, thereby bringing BCL10 gene under control of the IGH enhancer region, and this event results in overexpression of nuclear BCL10 protein[45]. BCL10 is essential for both the development and function of mature B and T cells, linking antigen-receptor signaling to the NF-κB pathway. The deregulated expression of wild-type BCL10 as a result of the translocation t (1; 14) seems to be one important event in MALT lymphomagenesis[47].

Clinical symptoms of primary gastric lymphoma are vague and varied, with abdominal pain being the most common complaint, followed by dyspepsia, vomiting and gastric bleeding[48-51]. Constitutional B symptoms are exceedingly uncommon. The endoscopic appearance of primary gastric lymphoma is variable and can be infiltrative, exophytic or ulcerative. In addition, primary gastric lymphoma may represent as multifocal disease within the stomach with numerous clonally identical lymphoma foci in apparently unaffected tissue[52]. A gastric mapping of macroscopically unaffected mucosa is therefore recommended and crucial for diagnosis. An important feature of gastric MALT lymphoma is the presence of lymphoepithelial lesions formed by invasion of individual glands by aggregates of lymphoma cells with centrocyte like morphology[3], whereas aggressive lymphoma occur as infiltration of centroblast-like lymphocytes[53]. In difficult to diagnose cases, B-cell clonality, assessed by PCR for amplification of the VDJ region of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene (IgH), is used to support the diagnosis of gastric MALT lymphoma[54]. The presence of H pylori infection should be diagnosed with routine biopsies taken and/or rapid urease test. In case of negativity, serology should be performed to identify truly negative gastric MALT lymphomas. Once the diagnosis of gastric lymphoma has been established, the accurate determination of the extension of the disease is crucial for the therapeutic approach. The initial staging should comprise a gastroduodenal endoscopy combined with endoscopic ultrasound to determine the extent of the gastric wall involvement. This method is more accurate than CT scan for the detection of spread to perigastric lymph nodes[11,55,56], especially in limited stages. Furthermore, colonoscopy, bone marrow aspiration, examination of the pharynx, chest x-ray and abdominal ultrasound should be performed to exclude lymphoma spread to other lymphatic or extra-lymphatic organs.

The clinical stage will be determined in accordance with the Ann Arbor classification of extranodal NHL modified by Musshoff as proposed in 1977[57]. In 1994, this staging system was refined with emphasis on separate description of local penetration into neighbouring structures. The subdivision in stage III and IV disease was taken together and considered as widely disseminated disease. Radaszkiewicz et al[58] (1992) defined stadium I1 as involvement of mucosa and submucosa, stadium I2 as lymphoma extending beyond the submucosa, and differentiated stage II into disease with neighbouring (II1) and distant lymphnodes (II2). In 2003 Ruskoné-Fourmestraux et al[59] introduced a modified TNM classi-fication system, the Paris staging system, to adequately describe (1) depth of tumor infiltration, (2) extent of nodal involvement as well as (3) specific lymphoma spreading (Table 1), which tries to address the different behaviour of MALT-lymphoma, especially with respect to local infiltration.

| Paris staging system1,2 | |

| T stage | |

| TX | Lymphoma extend not specified |

| T0 | No evidence of lymphoma |

| T1 | Lymphoma confined to the mucosa/submucosa |

| T1m | Lymphoma confined to the mucosa |

| T1sm | Lymphoma confined to the submucosa |

| T2 | Lymphoma infiltrates muscularis propria or subserosa |

| T3 | Lymphoma penetrates serosa (visceral peritoneum) without invasion of adjacent structures |

| T4 | Lymphoma invades adjacent structures or organs |

| N stage | |

| NX | Involvement of lymph nodes not assessed |

| N0 | No evidence of lymph node involvement |

| N13 | Involvement of regional lymph nodes |

| N2 | Involvement of intra-abdominal lymph nodes beyond the regional area |

| N3 | Spread to extra-abdominal lymph nodes |

| M stage | |

| Mx | Dissemination of lymphoma not assessed |

| M0 | No evidence of extranodal dissemination |

| M1 | Non-continuous involvement of separate site in gastrointestinal tract (e.g. stomach and rectum) |

| M2 | Non-continuous involvement of other tissues (e.g. peritoneum, pleura) or organs (e.g. tonsils, parotid gland, ocular adnexa, lung, liver, spleen, kidney etc.) |

| B stage | |

| BX | Involvement of bone marrow not assessed |

| B0 | No evidence of bone marrow involvement |

| B1 | Lymphomatous infiltration of bone marrow |

| TNMB | Clinical staging: status of tumour, node, metastasis, bone marrow |

| pTNMB | Histopathological staging: status of tumour, node, metastasis, bone marrow |

| pN: | The histological examination will ordinarily include 6 or more lymph nodes |

The most effective management of primary gastric lymphoma depends on the exact diagnosis of the lymphoma, the accurate clinical staging of the disease, and the presence of H pylori infection. Despite a load of literature on different therapeutic strategies for patients with gastric MALT lymphoma, published data sometimes are confusing: insufficient staging and outdated histologic classifications are a major problem of the older reports, and more recent studies often refer to retrospective studies of patients not uniformly staged and treated.

However, most studies report on treatment outcomes for localized gastric MALT lymphoma. Patients have been treated with a variety of combinations of surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy including H pylori eradication and a watch-and-wait strategy, but the optimal therapeutic algorithm for patient management still remains to be determined.

As indicated earlier, experimental data have extended the knowledge of the mere association of gastric MALT lymphoma and infection with H pylori. The perception that growth of low-grade MALT lymphoma is modulated in vitro by H pylori-related factors, and that cure of the infection may influence tumour growth leading to lymphoma remission started in 1992. Meanwhile, many clinical studies have shown that cure of H pylori infection is associated with complete remission of gastric MALT lymphoma in approximately 80% of patients with H pylori-positive gastric low-grade MALT lymphoma in stage I[14-25,60]; but until recently only few data existed on the long-term stability of the remissions induced. A recent paper by Wündisch and co-workers[24] report on the long-term follow up of 120 patients with stageIdisease. The median follow-up was 75 (range: 1-116) mo, and five-year survival was 90%. Overall, 80% of patients achieved a complete histologic remission (CR) with 80% of them being in continuous complete remission (CCR). Only 3% showed clinical lymphoma relapse and were referred to alternative treatment strategies. These findings suggest that at least a fraction of the patients may actually be cured from their lymphoma by a therapy directed against the underlying infection only. Histologic residual disease (RD) and ongoing B-cell clonality are present in a considerable number of patients[61]. But due to the indolent nature of the lymphoma a careful watch-and-wait strategy seems to be justified[24,25]. To date, eradication therapy in H pylori-positive, primary gastric MALT lymphoma patients with localized stageIdisease has to be considered as treatment of choice with any of the highly effective antibiotic regimens proposed can be used[62,63]. The role of eradication therapy in stage II lymphomas is still under discussion. Treatment success is lower, being only 40% in stage II1[20,55]. In any case, a strict endoscopic follow-up is recommended. Current protocols recommend to wait at least for 12 mo after successful eradication therapy before a non-responder is defined and second-line therapy is applied. Long-term follow-up of antibiotic treated patients is mandatory.

Many patients, approximately 20%, with H pylori-positive, early stage gastric MALT lymphoma do not respond to eradication therapy with complete lymphoma remission. They may show lymphoma progression or, more often, persistent lymphoma infiltrates despite normal endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasound examination. For those patients, the term minimal residual disease has been postulated. The consensus has been that these patients should be referred to further oncological treatment. However, in a recent report by Fischbach and colleagues[64], seven patients with so called minimal residual disease after eradication therapy refused any further treatment, but nevertheless agreed to regular follow-up. Despite persistent B-cell clonality, neither lymphoma progression nor high-grade transformation arose during a mean observation period of 34 (range 22-44) mo. In view of the favourable course of these patients, a watch-and-wait strategy could be a valid approach to the management of this disease in individual cases, taking into account the clinical situation of the patient (age, comorbidities) as well as potential risk factors (molecular markers). Very thorough investigations are, however, mandatory when deciding to do so.

Approximately 5% to 10% of gastric MALT lymphomas are H pylori negative, and the pathogenesis of these cases is poorly understood[65]. For the definite diagnosis of H pylori negativity in case of negative biopsy specimens, serological analysis for CagA antibodies and H pylori-IgG antibodies should be performed[66], and other Helicobacter species such as H heilmannii or H felis should be excluded[19,67]. Possible pathogenic mechanisms that are currently under discussion for H pylori-negative gastric MALT lymphomas include hepatitis C virus infection[68,69], autoimmune diseases[70], and the translocation t (11, 18)[71,72].

Currently, there are no guidelines how to treat patients with low-grade H pylori-negative gastric MALT lymphoma. So far, multiple treatment modalities including chemotherapy, surgery or local radiation have been used with various response and remission rates. The role of eradication therapy despite absence of the infection is currently under discussion. Analyzing predictive factors for complete lymphoma remission after eradication therapy it became evident that lack of H pylori infection adversely affects response to antibacterial treatment. As reported by Ruskoné-Fourmestraux and co-workers[20], 10 patients within the group of patients with low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma who received eradication therapy were H pylori negative, and none of them (23% of all cases) showed lymphoma remission, that is 40% of all non-responders. Hence, eradication treatment in patients with low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma, whatever the H pylori status is, is therefore of doubtful clinical relevance. Comparable results were documented in a paper by Steinbach and colleagues in which 6 patients with H pylori-negative gastric MALT lymphoma did also show no signs of lymphoma remission after antibiotic therapy[17]. In this analysis, not only the H pylori status seems to be important, but also the distribution of the lymphoma is probably related to the differing clinical course of these lymphomas. Steinbach et al postulated that proximal localized MALT lymphomas might either be H pylori associated or may be H pylori-independent autoimmune gastritis associated, which is generally proximal in distribution. Therefore, H pylori negativity and proximal localized MALT tumours seem to be negative predictive factors for fully response to antibiotic treatment. On the other hand, Raderer and co-workers report in a single center study on six patients with H pylori-negative localised gastric MALT lymphoma who underwent antibiotic treatment[73]. H pylori infection was ruled out by histology, urease breath test, serology, and stool antigen testing. Following antibiotic treatment, five patients responded with lymphoma regression between three and nine months (one partial remission and four complete responses). One patient had stable disease for 12 mo and was then referred for chemotherapy.

Based on the patients compliance and the patients decision concerning other oncological treatment approaches, eradication therapy might be an individualized option, but can clearly not be recommended generally in all H pylori-negative patients.

Surgery has long been the therapeutic standard approach for gastric lymphoma. It was important in the diagnosis, staging, and management of early stage disease. The exact histological composition of the lymphoma based on a resected stomach as well as the pathological staging has always been an accurate and reproducible diagnostic tool. Several series demonstrated five-year survival rates of over 90% with resection alone[74,75]. In a meta-analysis of 80 studies investigating more than 3500 patients with gastric lymphoma, 83% of them were treated primarily by surgery[76]. The 5-year-survival rate (60%) was significantly higher when compared to the conservative treatment approach, i.e. chemo- or radiotherapy. However, complication rates for gastrectomy and extensive lymphadenectomy occur in up to 50% of patients[74]. Thus, while surgery can clearly result in excellent survival for patients with localized disease, it is associated with both short-term and long-term morbidity.

Several German Multicenter Study Groups did clearly show that an organ-preserving approach for early gastric lymphoma is not inferior to primary surgery[77,78]. There was no significant difference in survival between surgery and nonsurgery groups. The overall 5-year survival rate was 82% and 84%, respectively[77]. In a recent, again nonrandomized multicenter trial, these results were confirmed in almost 750 patients[48]. In addition, two randomized studies by Avilés et al[79,80] further supported that surgery could be omitted from primary treatment of early gastric lymphoma. Most contemporary treatment algorithms no longer include surgical resection in the primary treatment of gastric lymphoma and reserve surgery for the management of complications or unique cases of locally persistent disease.

Since surgery was the preferred approach for a long time, the curative potential of radiotherapy as conservative strategy alone, or in combination with chemotherapy first became clear when interest in non-invasive treatment modalities became evident. MALT lymphomas have recently been reported as being highly sensitive to radiotherapy[77,81-84] and treatment is potentially curative for those with localized stageIand II. Involved field radiotherapy is therefore applied with doses of 30 to 35 Gy to the entire stomach, paragastric and celiac lymph nodes resulting in > 95% local control. The limit of the total dose to both kidneys should be < 20 Gy, while keeping a significant volume of liver (> 50%) exposed to low doses (< 25 Gy)[83,85]. Fields should be shaped with multi-leaf collimators to further minimize exposure of the liver and kidneys, and preliminary data suggest, that further dose reduction to 25.2 Gy in localized gastric MALT lymphoma might be as effective as doses of 30 to 35 Gy[86].

In planning radiation for the stomach the principle and technique similar to that used for gastric carcinoma can be adapted for use, hence, CT planning is indispensable. Although transient nausea and anorexia is common with radiotherapy, no serious long-term toxicity such as ulceration or hemorrhage has been observed with the 30 to 35 Gy doses[87], and relapse of gastric MALT lymphoma rarely occurs. The risk for the development of a second malignancy, such as adenocarcinoma, attributable to primary radiation, is low[88,89]. Generally, patients with gastric lymphoma tend to be at increased risk for gastric adenocarcinoma due to a common pathogenesis of both diseases, irrespective of the treatment modality[90-93].

In conclusion, radiotherapy is effective and safe and offers the significant advantage of low morbidity compared to surgery. It represents a curative treatment option for patients with gastric MALT lymphoma being H pylori-negative or unresponsive to eradication therapy with lack of complete lymphoma remission as part of a multistep treatment approach.

MZBCL of MALT type was long thought to be a localized disease, hence local treatment approaches, i.e. surgery and radiation were applied predominantly. Systemic dissemination, non-responder and recurrences after localized treatment have induced the evaluation of systemic treatment approaches[94,95]. Various chemotherapeutics including alkylating agents, nucleoside analogs or the combination of the latter have been tested but only limited data especially on untreated patients with localized disease exist to date. So far, there is no chemotherapeutic standard treatment for patients with MZBCL of MALT type either presenting with disseminated or relapsed or progressive disease after local treatment or after H pylori eradication. This fact is attributable to the lack of phase-III studies on the one hand, and the low prevalence of the disease on the other.

Complete remission (CR) rates of gastric MZBCL of MALT type in stageIafter oral monochemotherapy (OMC) with cyclophosphamide or chlorambucil are reported to range from 82% to 100%, and from 50% to 57% for stage IV disease[96,97]. In a recent study by Nakamura and co-workers from Japan a similar CR rate of 89% was achieved after OMC with cyclophosphamide 100 mg/d[98]. In this study, the results in CR rates after OMC were comparable to the CR rates achieved with radiotherapy, hence, OMC might also be a suitable second line therapeutic option after failure of first line treatment approach such as H pylori eradication. The presence of the translocation t (11; 18) has been shown to be a negative predictive factor for lymphoma response to eradication therapy. The role of this translocation for the prediction of response to chemotherapy is yet under investigation. Recent data have shown that for oral alkylating agents such as cyclophosphamide or chlorambucil the presence of t (11; 18) in gastric MZBCL of MALT type is predictive of resistance[99]. Complete remission rates of gastric MZBCL of MALT type after 1 and 8 years were 42% and 8% for t (11; 18)-positive, and 89% and 89% for t (11, 18)-negative patients, respectively (P = 0.0003, 8 years). Hence, oral alkylating agents might only be administered in patients with t (11; 18)-negative lymphoma.

A combination therapy with fludarabine plus mitoxantrone (FM) has also been shown to be effective in the frontline or salvage treatment in patients with non-gastrointestinal stageIMZBCL of MALT type. All patients (n = 20) treated with FM achieved complete lymphoma remission[100]. The treatment efficacy of FM was compared to a polychemotherapy regimen containing cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (CVP) (n = 11). Of those, 4 patients experienced disease recurrence after CVP therapy, achieving a second CR after FM salvage therapy. Hence, the fludarabine-containing regimen as frontline or salvage therapy seems to be superior to CVP in terms of efficacy at least in non-gastric MZBCL of MALT type. Polychemotherapy with mitoxantrone, chlorambucil, and prednisone (MCP) in chemotherapy-naïve patients with MZBCL of MALT type at various sites seems also to be an option with a good response rate over 80%[101]. However, CR rates are lower with only 53% after a median number of 5 cycles per patients. Subjective tolerance of chemotherapy is generally good, and toxicities are mainly mild. Grade 3 or 4 toxicity (WHO) is observed in up to 1/3 of patients treated with various mono- or polychemotherapy approaches, and mainly includes haematological adverse events such as leukocytopenia.

Based on the good therapeutic efficacy of the nucleoside analog fludarabine in nongastric MZBCL of MALT type[100] the administration of other nucleoside analogs, which have demonstrated therapeutic potential in various types of indolent lymphoma seems compelling. Cladribine or 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine [2-CdA] has been investigated in a phase-II study[102] in patients with gastric (n = 19) and nongastric (n = 7) MZBCL of MALT type at any stage. Patients had to be chemotherapy-naïve, not responding to H pylori eradication therapy in case of gastric lymphoma or suffering from a relapse after radiation therapy. In addition to the direct cytotoxic potential of this agent, 2-CdA is associated with a pronounced T-cell depletory activity. This additional effect may enhance efficacy of this drug in gastric MZBCL of MALT type due to the potential role of antigen-specific T-cells in lymphomagenesis[103,104]. 2-CdA was administered at a dose of 0.12 mg/kg body weight by intravenous infusion over 2 h on d 1 to 5, and was repeated every 4 wk. After a median number of 4 cycles virtually all patients responded to the treatment, and 84% achieved a complete lymphoma remission including all patients with a gastric lymphoma. In contrast to the oral alkylating agents, the presence of the translocation t (11; 18) does not adversely affect the response to 2-CdA chemotherapy[105]. However, 3 patients with gastric lymphoma have relapsed locally after 13, 18, and 22 mo, and were salvaged with radiotherapy. Approximately 38% of patients experienced toxicities of WHO grade 3 and 4 including mainly leukocytopenia, a herpes zoster in one patient, and cardiac toxicity in another. In the literature, some patients that have been treated with 2-CdA, developed a treatment-related mylodysplastic syndrome and acute leukaemia[106]. However, since these reports are rare, 2-CdA can be considered as a highly effective and relatively safe drug, and might therefore represent a good individual therapeutic option in patients with MZBCL of MALT type.

Platinum derivates have shown a broad range of anticancer activity. Oxaliplatin (L-OHP), a diaminocyclohexane (DACH) platinum, has shown a differential spectrum of cytotoxicity compared to cisplatin, with activity in primary or secondary cisplatin-resistant solid tumors. Also in terms of adverse events, it is substantially different from both carboplatin and cisplatin, and it has become part of standard therapy for advanced colorectal carcinoma.

The tolerance and activity of oxaliplatin has been investigated in patients with heavily pretreated refractory or recurrent non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Administered as single-agent therapy, the objective response rate is between 27% and 40%[107,108]. Combined oxaliplatin with high-dose cytarabine and dexamethasone (DHAOx) increases the response rate up to 73%[109,110]. However, due to combination therapy, toxic side effects are more common than in L-OHP single agent therapy with up to 75% neutropenia and 75% thrombocytopenia WHO grade 3 and 4[110]. After a closer look on these data on L-OHP efficacy in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, it becomes clear that the patients cohorts investigated are heterogeneous concerning the lymphoma entity and histology including up to 73% of patients with an aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma histology[107,108]. Therefore, a recent phase-II study by Raderer and co-workers evaluated the activity of single-agent L-OHP in MZBCL of MALT type[111]. Sixteen patients with a MZBCL of MALT type of various sites including 3 patients with a gastric lymphoma were treated with L-OHP 130 mg/m2 i.v. for 2 h, repeated every 21 d for a maximum of 6 cycles. After a median of 4 cycles, the objective response rate was 94%, with 9 patients (56%) achieving a complete remission. Of the 16 patients tested for the translocation t (11; 18), 11 (69%) were positive, but the presence of the translocation did not affect treatment outcome. So far, 1 patient relapsed after 12 mo, and 2 patients experienced progression 4 and 6 mo after partial response, respectively. Tolerance of therapy was excellent and no grade 3 or 4 toxicities were described. Only mild side effects were experienced such as sensory neuropathy WHO grade 2, nausea/emesis WHO grade 2 or anemia, leukocytopenia and thrombocytopenia WHO grade 1 and 2. Overall, L-OHP is highly effective and nontoxic in MZBCL of MALT type irrespective of the translocation status or previous treatment approaches, and might represent another individual rescue option.

Rituximab is a chimeric antibody targeting the CD20 epitope expressed on mature B-cells, and various types of lymphomas of the B cell lineage including gastric MZBCL express CD20, too. The clinical efficacy of this agent has first been demonstrated in follicular lymphoma[112]. Currently, the use of rituximab has been extended to other subtypes of non-Hodgkin lymphomas both as a single agent[112,113] or in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy[114-116]. Mechanisms responsible for the anti-lymphoma efficiacy of rituximab include immune-mediated effects, i.e. lysis and cytotoxicity, and direct effects induced by ligation of the epitope leading to apoptosis[117].

The efficacy of rituximab in patients with gastric MZBCL has not been extensively evaluated. The first phase II study was published in 2003 analysing rituximab monotherapy given at doses of 375 mg/m2 once weekly for 4 wk in patients with untreated and relapsed extranodal MZBCL at any stage[118]. Of 35 patients investigated, 15 had a primary gastric lymphoma. Only 2 patients were H pylori negative initially, the other patients had previous treatment attempts including eradication therapy, chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy. The study demonstrated a significant clinical activity of rituximab. The overall response rate (ORR) in primary gastric MZBCL was 64% with a 29% complete remission rate with only mild to moderate and self-limiting toxicity. However, prior receipt of chemotherapy resulted in a drop of ORR to 45%, and the relapse rate after end of treatment was high (36%) suggesting that the 4-weekly dosing regimen used may not be sufficient to achieve continuous complete remission. A retrospective analysis by Raderer and co-workers[119] in 9 unselected patients with advanced MZBCL at different sites that were treated with rituximab also given at doses of 375 mg/m2 once weekly for 4 wk are in line with the data presented by Conconi[118]. The objective response rate was 50% with a complete remission rate of 33%. However, results are interpreted with more caution in terms of inducing objective responses indicating that rituximab might not optimally penetrate into the gastric mucosa. Analysing a less heterogeneous cohort of patients with early stage disease, i.e. H pylori-negative gastric MZBCL, ORR is increasing over 70% with a complete remission rate of almost 45%[120,121]. Hence, in individual patients, rituximab monotherapy seems to be a good therapeutic option to induce complete lymphoma remission, and the prevalence of the translocation t (11; 18) seems not to have an effect on the lymphoma response to rituximab therapy[120,122].

Gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common lymphoma type arising in this organ. Transformation of MALT lymphoma to DLBCL has been described[7], and genetic evidence for a clonal link between low- and high-grade components do indeed exist. Hence some cases of gastric DLBCL are transformed MALT lymphomas, but others are true primary DLBCL. However, there is no difference in the clinical behaviour between transformed MALT lymphomas and primary DLBCL[42]. In some cases, H pylori infection, low-grade MALT component and DLBCL are present simultaneously. Regardless of H pylori infection, these malignancies have been termed "diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with concomitant low-grade MALT component"[2].

H pylori infection is found in 35% of gastric DLBCL, being more common in cases with a concomitant MALT component (65% versus 15%, respectively[123,124]. In contrast to tumor cells of gastric MALT lymphoma, the growth of high-grade lymphoma cells in vitro was independent on the presence of H pylori antigens or H pylori-specific T-cells[103], hence, the role of eradication therapy in H pylori-positive gastric DLBCL with or without concomitant MALT components remains unclear.

Recent retrospective and prospective studies as well as isolated case reports have shown that H pylori eradication in gastric DLBCL with concomitant MALT components in an early localized stage results in durable complete lymphoma remission in 50% to 63% of cases[125-131]. Hence, at least in an initial phase, high-grade lymphoma transformation is not necessarily associated with a loss of H pylori dependence and might therefore lead to complete lymphoma remission without any other additional oncological treatment. Despite these positive results, the standard approach for patients with gastric DLBCL stageIand II should include rituximab plus conventional-dose antracycline-containing chemotherapy, which may or may not be followed by radiation therapy[48,114,116]. In addition to chemotherapy, confirmed H pylori infection should always be eradicated to minimize the risk of low-grade relapse[132]. Surgery should only be performed in patients with massive bleeding or perforation.

Gastric MALT lymphoma has been incorporated into the WHO lymphoma classification, termed as extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT-type. Its pathogenesis has been extensively studied, and chronic H pylori infection has been clearly shown to play a causative role. The increasing insight into molecular genetics of gastric MALT lymphomas has deepened our understanding of clinical lymphoma behaviour, with the most relevant translocation t (11; 18) (q21; q21) being present in up to 40% of cases. The t (11; 18) translocation is seen more frequently in disseminated and advanced lymphomas, and it has been associated with early stage cases that do not respond to H pylori eradication.

Prior to any therapeutic approach, a thorough clinical staging procedure and the exact determination of H pylori status are of utmost importance. Clinical staging should be based on the modified Ann Arbor system or on the newly proposed TMNB-Paris staging system (Table 1) to allow optimal comparability of patients cohorts.

Based on the data given, there is increasing evidence that eradication therapy of H pylori can be effectively employed as the sole initial treatment of localized gastric MALT lymphoma. Diagnosis of lymphoma remission after eradication therapy may take up to 18 mo or even longer. Current protocols recommend to wait for at least 12 mo before a non-responder is defined and second-line therapy is applied. Long-term data also show, that these complete lymphoma remissions are stable for at least 10 years and patients are basically cured of their disease. The role of eradication therapy in truly H pylori-negative lymphomas, that is negativity by histology, urea-breath test and serology, is currently under discussion and not generally recommendable. For those patients, and for patients that do not achieve complete lymphoma remission after eradication treatment, second line therapeutic strategies should be employed. Conservative approaches such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy or the chimeric monoclonal antibody anti-CD20 represent good options with very good response rates and low toxicities, still harbouring a high curative potential. Surgery should only be performed in patients with gastric complications such as perforation of bleeding. In advanced lymphoma stages, chemotherapy is still the treatment of choice, but curative protocols are currently not available. However, newer cytotoxic agents such as platinum-derivates or purin-analogs might improve therapeutic efficacy also in advanced lymphoma stages.

In gastric high-grade lymphoma, either derived from a low-grade MALT counterpart or developed de novo, the conventional antracycline-based chemotherapy plus anti-CD-20 antibody, which may or may not be followed by radiation therapy, remains the treatment of choice. In case of H pylori infection, eradication therapy should always be performed to influence low-grade components and to minimize the low-grade relapse risk after successful radio-chemotherapy (Figure 1).

Up to date, the pathogenesis of gastric MALT lymphoma has extensively been studied and many insights have been gained. These insights, such as the translocation t (11; 18), should now been evaluated prospectively to further understand their relevance for therapeutic decisions. The aim should be a better patient stratification prior to therapeutic decisions to increase treatment success. In future it should be possible to characterize the individual patients profile including parameters such as lymphoma stage, H pylori status, translocation status, B-cell monoclonality and other possible markers to predict the individual risk for treatment failure for the chosen treatment option.

Conservative treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy should be analyzed further. Both options harbour a high curative potential, the first also for higher stages. In future, chemotherapy protocols should be combined to increase the number of patients. This engagement might allow phase-III studies to be performed with a larger scientific benefit.

The role of radiotherapy might be more important than currently thought of. Volume-reduced radiation protocols have shown a high curative efficacy in stageI and II lymphomas with lower toxicities when compared to conventional protocols. Furthermore, a dose reduction of less than 26 Gy is under investigation as for the efficacy and toxicity in patients with gastric MALT lymphoma stageIand II, and preliminary results are promising. The authors would currently recommend radiotherapy as treatment of choice in second line approach or H pylori-negative first line approach in patients with gastric MALT lymphoma stageIand II.

This paper is dedicated to Professor Brigitte Dragosics. Her enthusiasm for gastric lymphomas will never be forgotten.

S- Editor Zhu LH L- Editor Rampone B E- Editor Lu W

| 1. | Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J, Flandrin G, Muller-Hermelink HK, Vardiman J, Lister TA, Bloomfield CD. The World Health Organization classification of hematological malignancies report of the Clinical Advisory Committee Meeting, Airlie House, Virginia, November 1997. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:193-207. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 299] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 310] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J, Flandrin G, Muller-Hermelink HK, Vardiman J, Lister TA, Bloomfield CD. World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: report of the Clinical Advisory Committee meeting-Airlie House, Virginia, November 1997. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3835-3849. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Cavalli F, Isaacson PG, Gascoyne RD, Zucca E. MALT Lymphomas. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2001;241-258. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 108] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Isaacson P, Wright DH. Malignant lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. A distinctive type of B-cell lymphoma. Cancer. 1983;52:1410-1416. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wotherspoon AC, Ortiz-Hidalgo C, Falzon MR, Isaacson PG. Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis and primary B-cell gastric lymphoma. Lancet. 1991;338:1175-1176. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1293] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1177] [Article Influence: 35.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | de Jong D, van Dijk WC, van der Hulst RW, Boot H, Taal BG. CagA+ H. pylori strains and gastric lymphoma. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:2022-2023. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Chan JK, Ng CS, Isaacson PG. Relationship between high-grade lymphoma and low-grade B-cell mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (MALToma) of the stomach. Am J Pathol. 1990;136:1153-1164. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Farinha P, Gascoyne RD. Helicobacter pylori and MALT lymphoma. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1579-1605. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 116] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wyatt JI, Rathbone BJ. Immune response of the gastric mucosa to Campylobacter pylori. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1988;142:44-49. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 156] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Parsonnet J, Hansen S, Rodriguez L, Gelb AB, Warnke RA, Jellum E, Orentreich N, Vogelman JH, Friedman GD. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1267-1271. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1287] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1204] [Article Influence: 40.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ahmad A, Govil Y, Frank BB. Gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:975-986. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 107] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hussell T, Isaacson PG, Crabtree JE, Spencer J. The response of cells from low-grade B-cell gastric lymphomas of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue to Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1993;342:571-574. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 571] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 592] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wotherspoon AC, Doglioni C, Diss TC, Pan L, Moschini A, de Boni M, Isaacson PG. Regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1993;342:575-577. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1504] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1354] [Article Influence: 43.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bayerdörffer E, Neubauer A, Rudolph B, Thiede C, Lehn N, Eidt S, Stolte M. Regression of primary gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after cure of Helicobacter pylori infection. MALT Lymphoma Study Group. Lancet. 1995;345:1591-1594. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 652] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 677] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Roggero E, Zucca E, Pinotti G, Pascarella A, Capella C, Savio A, Pedrinis E, Paterlini A, Venco A, Cavalli F. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection in primary low-grade gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:767-769. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 319] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Neubauer A, Thiede C, Morgner A, Alpen B, Ritter M, Neubauer B, Wündisch T, Ehninger G, Stolte M, Bayerdörffer E. Cure of Helicobacter pylori infection and duration of remission of low-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1350-1355. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 217] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Steinbach G, Ford R, Glober G, Sample D, Hagemeister FB, Lynch PM, McLaughlin PW, Rodriguez MA, Romaguera JE, Sarris AH. Antibiotic treatment of gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. An uncontrolled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:88-95. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 169] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Savio A, Zamboni G, Capelli P, Negrini R, Santandrea G, Scarpa A, Fuini A, Pasini F, Ambrosetti A, Paterlini A. Relapse of low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma after Helicobacter pylori eradication: true relapse or persistence? Long-term post-treatment follow-up of a multicenter trial in the north-east of Italy and evaluation of the diagnostic protocol's adequacy. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2000;156:116-124. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Morgner A, Lehn N, Andersen LP, Thiede C, Bennedsen M, Trebesius K, Neubauer B, Neubauer A, Stolte M, Bayerdörffer E. Helicobacter heilmannii-associated primary gastric low-grade MALT lymphoma: complete remission after curing the infection. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:821-828. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 215] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ruskoné-Fourmestraux A, Lavergne A, Aegerter PH, Megraud F, Palazzo L, de Mascarel A, Molina T, Rambaud JL. Predictive factors for regression of gastric MALT lymphoma after anti-Helicobacter pylori treatment. Gut. 2001;48:297-303. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 230] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Suekane H, Takeshita M, Hizawa K, Kawasaki M, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M, Iida M, Fujishima M. Predictive value of endoscopic ultrasonography for regression of gastric low grade and high grade MALT lymphomas after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 2001;48:454-460. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 187] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Stolte M, Bayerdörffer E, Morgner A, Alpen B, Wündisch T, Thiede C, Neubauer A. Helicobacter and gastric MALT lymphoma. Gut. 2002;50 Suppl 3:III19-III24. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 123] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Fischbach W, Goebeler-Kolve ME, Dragosics B, Greiner A, Stolte M. Long term outcome of patients with gastric marginal zone B cell lymphoma of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) following exclusive Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: experience from a large prospective series. Gut. 2004;53:34-37. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 256] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wündisch T, Thiede C, Morgner A, Dempfle A, Günther A, Liu H, Ye H, Du MQ, Kim TD, Bayerdörffer E. Long-term follow-up of gastric MALT lymphoma after Helicobacter pylori eradication. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8018-8024. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 245] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wündisch T, Mösch C, Neubauer A, Stolte M. Helicobacter pylori eradication in gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: Results of a 196-patient series. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:2110-2114. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Streubel B, Vinatzer U, Lamprecht A, Raderer M, Chott A. T(3; 14)(p14.1; q32) involving IGH and FOXP1 is a novel recurrent chromosomal aberration in MALT lymphoma. Leukemia. 2005;19:652-658. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Streubel B, Lamprecht A, Dierlamm J, Cerroni L, Stolte M, Ott G, Raderer M, Chott A. T(14; 18)(q32; q21) involving IGH and MALT1 is a frequent chromosomal aberration in MALT lymphoma. Blood. 2003;101:2335-2339. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 364] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 382] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Peng H, Diss T, Isaacson PG, Pan L. c-myc gene abnormalities in mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas. J Pathol. 1997;181:381-386. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Martinez-Delgado B, Robledo M, Arranz E, Osorio A, García MJ, Echezarreta G, Rivas C, Benitez J. Hypermethylation of p15/ink4b/MTS2 gene is differentially implicated among non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Leukemia. 1998;12:937-941. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Grønbaek K, Straten PT, Ralfkiaer E, Ahrenkiel V, Andersen MK, Hansen NE, Zeuthen J, Hou-Jensen K, Guldberg P. Somatic Fas mutations in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: association with extranodal disease and autoimmunity. Blood. 1998;92:3018-3024. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Martinez-Delgado B, Fernandez-Piqueras J, Garcia MJ, Arranz E, Gallego J, Rivas C, Robledo M, Benitez J. Hypermethylation of a 5' CpG island of p16 is a frequent event in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Leukemia. 1997;11:425-428. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ohashi S, Segawa K, Okamura S, Urano H, Kanamori S, Ishikawa H, Hara K, Hukutomi A, Shirai K, Maeda M. A clinicopathologic study of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Cancer. 2000;88:2210-2219. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ott G, Katzenberger T, Greiner A, Kalla J, Rosenwald A, Heinrich U, Ott MM, Müller-Hermelink HK. The t(11; 18)(q21; q21) chromosome translocation is a frequent and specific aberration in low-grade but not high-grade malignant non-Hodgkin's lymphomas of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT-) type. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3944-3948. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Auer IA, Gascoyne RD, Connors JM, Cotter FE, Greiner TC, Sanger WG, Horsman DE. t(11; 18)(q21; q21) is the most common translocation in MALT lymphomas. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:979-985. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 208] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Baens M, Maes B, Steyls A, Geboes K, Marynen P, De Wolf-Peeters C. The product of the t(11; 18), an API2-MLT fusion, marks nearly half of gastric MALT type lymphomas without large cell proliferation. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1433-1439. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 159] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Liu H, Ruskon-Fourmestraux A, Lavergne-Slove A, Ye H, Molina T, Bouhnik Y, Hamoudi RA, Diss TC, Dogan A, Megraud F. Resistance of t(11; 18) positive gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma to Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Lancet. 2001;357:39-40. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 333] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 346] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Liu H, Ye H, Ruskone-Fourmestraux A, De Jong D, Pileri S, Thiede C, Lavergne A, Boot H, Caletti G, Wündisch T. T(11; 18) is a marker for all stage gastric MALT lymphomas that will not respond to H. pylori eradication. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1286-1294. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 258] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Dierlamm J, Baens M, Wlodarska I, Stefanova-Ouzounova M, Hernandez JM, Hossfeld DK, De Wolf-Peeters C, Hagemeijer A, Van den Berghe H, Marynen P. The apoptosis inhibitor gene API2 and a novel 18q gene, MLT, are recurrently rearranged in the t(11; 18)(q21; q21) associated with mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas. Blood. 1999;93:3601-3609. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 39. | Akagi T, Motegi M, Tamura A, Suzuki R, Hosokawa Y, Suzuki H, Ota H, Nakamura S, Morishima Y, Taniwaki M. A novel gene, MALT1 at 18q21, is involved in t(11; 18) (q21; q21) found in low-grade B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Oncogene. 1999;18:5785-5794. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 276] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Lucas PC, Yonezumi M, Inohara N, McAllister-Lucas LM, Abazeed ME, Chen FF, Yamaoka S, Seto M, Nunez G. Bcl10 and MALT1, independent targets of chromosomal translocation in malt lymphoma, cooperate in a novel NF-kappa B signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19012-19019. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 341] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Uren AG, O'Rourke K, Aravind LA, Pisabarro MT, Seshagiri S, Koonin EV, Dixit VM. Identification of paracaspases and metacaspases: two ancient families of caspase-like proteins, one of which plays a key role in MALT lymphoma. Mol Cell. 2000;6:961-967. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 42. | Cogliatti SB, Schmid U, Schumacher U, Eckert F, Hansmann ML, Hedderich J, Takahashi H, Lennert K. Primary B-cell gastric lymphoma: a clinicopathological study of 145 patients. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:1159-1170. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 43. | Alpen B, Neubauer A, Dierlamm J, Marynen P, Thiede C, Bayerdörfer E, Stolte M. Translocation t(11; 18) absent in early gastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT type responding to eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Blood. 2000;95:4014-4015. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 44. | Nakamura T, Nakamura S, Yonezumi M, Suzuki T, Matsuura A, Yatabe Y, Yokoi T, Ohashi K, Seto M. Helicobacter pylori and the t(11; 18)(q21; q21) translocation in gastric low-grade B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2000;91:301-309. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 49] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Ye H, Dogan A, Karran L, Willis TG, Chen L, Wlodarska I, Dyer MJ, Isaacson PG, Du MQ. BCL10 expression in normal and neoplastic lymphoid tissue. Nuclear localization in MALT lymphoma. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1147-1154. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 144] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Achuthan R, Bell SM, Leek JP, Roberts P, Horgan K, Markham AF, Selby PJ, MacLennan KA. Novel translocation of the BCL10 gene in a case of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;29:347-349. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Farinha P, Gascoyne RD. Molecular pathogenesis of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6370-6378. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 146] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Koch P, Probst A, Berdel WE, Willich NA, Reinartz G, Brockmann J, Liersch R, del Valle F, Clasen H, Hirt C. Treatment results in localized primary gastric lymphoma: data of patients registered within the German multicenter study (GIT NHL 02/96). J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7050-7059. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 191] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Montalbán C, Castrillo JM, Abraira V, Serrano M, Bellas C, Piris MA, Carrion R, Cruz MA, Laraña JG, Menarguez J. Gastric B-cell mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. Clinicopathological study and evaluation of the prognostic factors in 143 patients. Ann Oncol. 1995;6:355-362. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 50. | Pinotti G, Zucca E, Roggero E, Pascarella A, Bertoni F, Savio A, Savio E, Capella C, Pedrinis E, Saletti P. Clinical features, treatment and outcome in a series of 93 patients with low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 1997;26:527-537. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 51. | Kolve M, Fischbach W, Greiner A, Wilms K. Differences in endoscopic and clinicopathological features of primary and secondary gastric non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. German Gastrointestinal Lymphoma Study Group. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:307-315. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 51] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Wotherspoon AC, Doglioni C, Isaacson PG. Low-grade gastric B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT): a multifocal disease. Histopathology. 1992;20:29-34. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 124] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Kluin PM, van Krieken JH, Kleiverda K, Kluin-Nelemans HC. Discordant morphologic characteristics of B-cell lymphomas in bone marrow and lymph node biopsies. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;94:59-66. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 54. | Hummel M, Oeschger S, Barth TF, Loddenkemper C, Cogliatti SB, Marx A, Wacker HH, Feller AC, Bernd HW, Hansmann ML. Wotherspoon criteria combined with B cell clonality analysis by advanced polymerase chain reaction technology discriminates covert gastric marginal zone lymphoma from chronic gastritis. Gut. 2006;55:782-787. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Sackmann M, Morgner A, Rudolph B, Neubauer A, Thiede C, Schulz H, Kraemer W, Boersch G, Rohde P, Seifert E. Regression of gastric MALT lymphoma after eradication of Helicobacter pylori is predicted by endosonographic staging. MALT Lymphoma Study Group. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1087-1090. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 203] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Hoepffner N, Lahme T, Gilly J, Menzel J, Koch P, Foerster EC. Value of endosonography in diagnostic staging of primary gastric lymphoma (MALT type). Med Klin (Munich). 2003;98:313-317. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Musshoff K. Clinical staging classification of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas (author's transl). Strahlentherapie. 1977;153:218-221. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 58. | Radaszkiewicz T, Dragosics B, Bauer P. Gastrointestinal malignant lymphomas of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue: factors relevant to prognosis. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1628-1638. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 59. | Ruskoné-Fourmestraux A, Dragosics B, Morgner A, Wotherspoon A, De Jong D. Paris staging system for primary gastrointestinal lymphomas. Gut. 2003;52:912-913. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 122] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Morgner A, Bayerdörffer E, Neubauer A, Stolte M. Malignant tumors of the stomach. Gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma and Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2000;29:593-607. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Thiede C, Wündisch T, Alpen B, Neubauer B, Morgner A, Schmitz M, Ehninger G, Stolte M, Bayerdörffer E, Neubauer A. Long-term persistence of monoclonal B cells after cure of Helicobacter pylori infection and complete histologic remission in gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1600-1609. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 62. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain C, Bazzoli F, El-Omar E, Graham D, Hunt R, Rokkas T, Vakil N, Kuipers EJ. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56:772-781. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1348] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1286] [Article Influence: 75.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Morgner A, Labenz J, Miehlke S. Effective regimens for the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2006;15:995-1016. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Fischbach W, Goebeler-Kolve M, Starostik P, Greiner A, Müller-Hermelink HK. Minimal residual low-grade gastric MALT-type lymphoma after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 2002;360:547-548. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 60] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Hamajima N, Matuo K, Watanabe Y, Suzuki T, Nakamura T, Matsuura A, Yamao K, Ohashi K, Tominaga S. A pilot study to evaluate stomach cancer risk reduction by Helicobacter pylori eradication. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:764-765. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Everhart JE, Kruszon-Moran D, Perez-Perez G. Reliability of Helicobacter pylori and CagA serological assays. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2002;9:412-416. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 67. | Fox JG. The non-H pylori helicobacters: their expanding role in gastrointestinal and systemic diseases. Gut. 2002;50:273-283. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 220] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Catassi C, Fabiani E, Coppa GV, Gabrielli A, Centurioni R, Leoni P, Barbato M, Viola F, Martelli M, De Renzo A. High prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma at the onset. Preliminary results of an Italian multicenter study. Recenti Prog Med. 1998;89:63-67. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 69. | De Vita S, De Re V, Sansonno D, Sorrentino D, Corte RL, Pivetta B, Gasparotto D, Racanelli V, Marzotto A, Labombarda A. Gastric mucosa as an additional extrahepatic localization of hepatitis C virus: viral detection in gastric low-grade lymphoma associated with autoimmune disease and in chronic gastritis. Hepatology. 2000;31:182-189. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 69] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Leandro MJ, Isenberg DA. Rheumatic diseases and malignancy--is there an association? Scand J Rheumatol. 2001;30:185-188. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 69] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Ye H, Liu H, Attygalle A, Wotherspoon AC, Nicholson AG, Charlotte F, Leblond V, Speight P, Goodlad J, Lavergne-Slove A. Variable frequencies of t(11; 18)(q21; q21) in MALT lymphomas of different sites: significant association with CagA strains of H pylori in gastric MALT lymphoma. Blood. 2003;102:1012-1018. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 261] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Nakamura T, Nakamura S, Yonezumi M, Seto M, Yokoi T. The t(11; 18)(q21; q21) translocation in H. pylori-negative low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3314-3315. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Raderer M, Streubel B, Wöhrer S, Häfner M, Chott A. Successful antibiotic treatment of Helicobacter pylori negative gastric mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas. Gut. 2006;55:616-618. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 99] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Bartlett DL, Karpeh MS, Filippa DA, Brennan MF. Long-term follow-up after curative surgery for early gastric lymphoma. Ann Surg. 1996;223:53-62. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 51] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Kodera Y, Yamamura Y, Nakamura S, Shimizu Y, Torii A, Hirai T, Yasui K, Morimoto T, Kato T, Kito T. The role of radical gastrectomy with systematic lymphadenectomy for the diagnosis and treatment of primary gastric lymphoma. Ann Surg. 1998;227:45-50. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Brands F, Mönig SP, Raab M. Treatment and prognosis of gastric lymphoma. Eur J Surg. 1997;163:803-813. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 77. | Koch P, del Valle F, Berdel WE, Willich NA, Reers B, Hiddemann W, Grothaus-Pinke B, Reinartz G, Brockmann J, Temmesfeld A. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: II. Combined surgical and conservative or conservative management only in localized gastric lymphoma--results of the prospective German Multicenter Study GIT NHL 01/92. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3874-3883. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 78. | Fischbach W, Dragosics B, Kolve-Goebeler ME, Ohmann C, Greiner A, Yang Q, Böhm S, Verreet P, Horstmann O, Busch M. Primary gastric B-cell lymphoma: results of a prospective multicenter study. The German-Austrian Gastrointestinal Lymphoma Study Group. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1191-1202. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 131] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Avilés A, Nambo MJ, Neri N, Huerta-Guzmán J, Cuadra I, Alvarado I, Castañeda C, Fernández R, González M. The role of surgery in primary gastric lymphoma: results of a controlled clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2004;240:44-50. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 110] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Avilés A, Nambo MJ, Neri N, Talavera A, Cleto S. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma of the stomach: results of a controlled clinical trial. Med Oncol. 2005;22:57-62. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 78] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Schechter NR, Yahalom J. Low-grade MALT lymphoma of the stomach: a review of treatment options. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;46:1093-1103. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 67] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Schechter NR, Portlock CS, Yahalom J. Treatment of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the stomach with radiation alone. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1916-1921. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 83. | Tsang RW, Gospodarowicz MK, Pintilie M, Wells W, Hodgson DC, Sun A, Crump M, Patterson BJ. Localized mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma treated with radiation therapy has excellent clinical outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4157-4164. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 284] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 254] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Tsang RW, Gospodarowicz MK. Radiation therapy for localized low-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Hematol Oncol. 2005;23:10-17. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 61] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Hitchcock S, Ng AK, Fisher DC, Silver B, Bernardo MP, Dorfman DM, Mauch PM. Treatment outcome of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue/marginal zone non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:1058-1066. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Schmelz R, Thiede C, Dragosics B, Ruskoné-Formestraux A, Herrmann T, Dawel M, Ehninger G, Miehlke S, Stolte M, Morgner A. HELYX Study Part I & II: Treatment of low-grade gastric non-Hodgkin‘s lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type stages I & II1, an interim analysis. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:A295 (Abstract). [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 87. | Mittal B, Wasserman TH, Griffith RC. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the stomach. Am J Gastroenterol. 1983;78:780-787. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 88. | Ettinger DS, Carter D. Gastric carcinoma 16 years after gastric lymphoma irradiation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1977;68:485-488. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 89. | Shani A, Schutt AJ, Weiland LH. Primary gastric malignant lymphoma followed by gastric adenocarcinoma: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Cancer. 1978;42:2039-2044. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Morgner A, Miehlke S, Stolte M, Neubauer A, Alpen B, Thiede C, Klann H, Hierlmeier FX, Ell C, Ehninger G. Development of early gastric cancer 4 and 5 years after complete remission of Helicobacter pylori associated gastric low grade marginal zone B cell lymphoma of MALT type. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:248-253. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 91. | Baron BW, Bitter MA, Baron JM, Bostwick DG. Gastric adenocarcinoma after gastric lymphoma. Cancer. 1987;60:1876-1882. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Griffiths AP, Wyatt J, Jack AS, Dixon MF. Lymphocytic gastritis, gastric adenocarcinoma, and primary gastric lymphoma. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47:1123-1124. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Montalban C, Manzanal A, Boixeda D, Redondo C, Bellas C. Treatment of low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma with Helicobacter pylori eradication. Lancet. 1995;345:798-799. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Raderer M, Vorbeck F, Formanek M, Osterreicher C, Valencak J, Penz M, Kornek G, Hamilton G, Dragosics B, Chott A. Importance of extensive staging in patients with mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT)-type lymphoma. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:454-457. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 135] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Wenzel C, Fiebiger W, Dieckmann K, Formanek M, Chott A, Raderer M. Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue of the head and neck area: high rate of disease recurrence following local therapy. Cancer. 2003;97:2236-2241. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 80] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Blazquez M, Haioun C, Chaumette MT, Gaulard P, Reyes F, Soulé JC, Delchier JC. Low grade B cell mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the stomach: clinical and endoscopic features, treatment, and outcome. Gut. 1992;33:1621-1625. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Hammel P, Haioun C, Chaumette MT, Gaulard P, Divine M, Reyes F, Delchier JC. Efficacy of single-agent chemotherapy in low-grade B-cell mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma with prominent gastric expression. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2524-2529. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 98. | Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Suekane H, Nakamura S, Matsumoto H, Esaki M, Yao T, Iida M. Long-term clinical outcome of Helicobacter pylori eradication for gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma with a reference to second-line treatment. Cancer. 2005;104:532-540. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 67] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Lévy M, Copie-Bergman C, Gameiro C, Chaumette MT, Delfau-Larue MH, Haioun C, Charachon A, Hemery F, Gaulard P, Leroy K. Prognostic value of translocation t(11; 18) in tumoral response of low-grade gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type to oral chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5061-5066. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 98] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Zinzani PL, Stefoni V, Musuraca G, Tani M, Alinari L, Gabriele A, Marchi E, Pileri S, Baccarani M. Fludarabine-containing chemotherapy as frontline treatment of nongastrointestinal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Cancer. 2004;100:2190-2194. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 71] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Wöhrer S, Drach J, Hejna M, Scheithauer W, Dirisamer A, Püspök A, Chott A, Raderer M. Treatment of extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) with mitoxantrone, chlorambucil and prednisone (MCP). Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1758-1761. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 53] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |