Published online Nov 15, 2004. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i22.3339

Revised: April 4, 2004

Accepted: April 7, 2004

Published online: November 15, 2004

AIM: Leakage from oesophageal anastomosis is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. This study presented a novel, safe and effective double stapled technique for oesophago-enteric anastomosis.

METHODS: The data were obtained prospectively from hospital held clinical database. Thirty nine patients (26 males, 13 females) underwent upper-gastrointestinal resection between 1996 and 2000 for carcinoma (n = 36), gastric lymphoma (n = 1), and benign pathology (n = 2). Double stapled oesophago-enteric anastomosis was performed in all cases.

RESULTS: No anastomotic leak was reported. In cases of malignancy, the resected margins were free of neoplasm. Three deaths occurred, which were not related to anastomotic complications.

CONCLUSION: Even though the reported study is an uncontrolled one, the technique described is reliable, and effective for oesophago-enteric anastomosis.

- Citation: Kotru A, John AK, Dewar EP. A double stapled technique for oesophago-enteric anastomosis. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10(22): 3339-3341

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v10/i22/3339.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v10.i22.3339

Leakage is a major problem associated with oesophago-enteric anastomosis. The anastomosis may be hand sewn or stapled[1-4]. Even though there is no proven advantage between either techniques, basic principles of anastomosis surgery- tension free, good vascularity, and good mucosal apposition apply to both. A technique of double stapled anastomosis avoids stretch at oesophageal side of anastomosis and circumvents damage to vascularity.

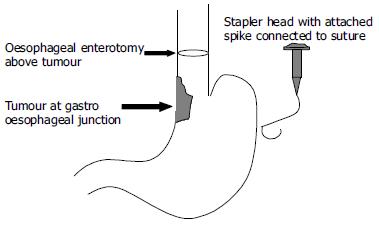

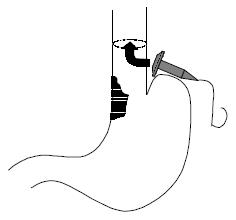

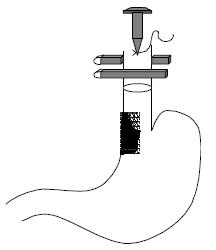

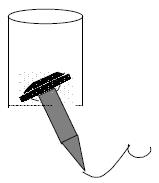

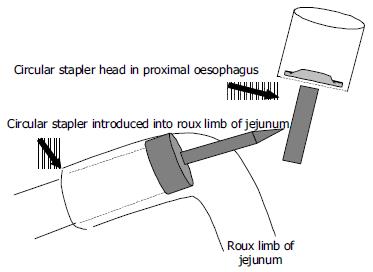

The double stapled oesophago-enteric reconstruction was performed as follows. The oesophagus was mobilized in the standard way to above the proposed level of division. A transverse incision was made in the anterior wall of the oesophagus at least 3 cm above the proximal extent of the tumour in those cases undergoing surgery for malignancy (Figure 1). An appropriately sized circular stapler (CA Ethicon) was selected based on the oesophageal diameter. A 2-0 polypropylene suture was placed through the 'eye-hole' situated in the plastic spike that fits the head of the circular stapler. The polypropylene suture should be tied such that around 5 cm of suture with the attached needle remained attached to the spike attached to the circular stapler head. The transverse anterior oesophagotomy should be of sufficient size to allow insertion of the stapler head with attached spike - see step 7 (Figure 2). The circular stapler head with spike and attached needle were placed through the oesophagotomy into the proximal oesophagus (Figure 3). The suture needle was brought out through the anterior oesophageal wall 2 cm proximal to the oesophagotomy. The oesophagus was then cross-stapled and divided transversely below the site of needle puncture but above the oesophagotomy. The suture attached to the spike was used to pull the spike and axis of the circular stapler head through the anterior wall of the oesophagus, around 2 cm proximal to the transverse staple line (Figure 4). The spike was then removed from the stapler head. Resection of the gastric or oesophago-gastric specimen was then completed. The distal conduit (either distal stomach or jejunal limb) was prepared and mobilized to allow a tension free anastomosis. The body of the circular stapler was introduced into the lumen of the efferent conduit through an appropriately placed enterotomy (Figure 5). The circular stapler head was engaged with the body of the circular stapler gun. The gun was closed and fired creating a double stapled oesophago-enteric anastomosis (Figure 5). A naso-gastric tube was fed across the oesophago-enterostomy after completion of the anastomosis.

All patients were operated on by or under the direct supervision of a consultant surgeon with an upper gastrointestinal interest. Patients with malignancy underwent pre-operative staging with thoraco-abdominal computed tomography scan. Laparoscopy was used in selected instances. In elective cases, mechanical bowel preparation was employed. Thoracic epidural anaesthesia was employed for post-operative pain relief. Patients were kept nil by mouth for 5 d post-operatively. If the post-operative course was uneventful, fluids were introduced on d 5. Water soluble contrast studies were not routinely used to assess anastomotic integrity unless there was clinical indication.

Data were obtained prospectively from the hospital-held clinical database.

Thirty-nine patients (26 males, 13 females) underwent upper gastrointestinal resection (total gastrectomy n = 24, Ivor -Lewis oesophago-gastrectomy n = 15) between 1996 and 2000. Indication for surgery was carcinoma (n = 36), gastric non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (n = 1), revision of a neo-gastric jejunal pouch (n = 1), gastric infarction secondary to volvulus (n = 1). The median age was 67 (36-82) years. Patient ASA grades were: ASA-1 n = 12, ASA-2 n = 14, ASA-3 n = 9, ASA-4 n = 3, ASA-5 n = 1. The median operative time for total gastrectomy was 175 (120-240) min and was 240 (180-360) min for Ivor-Lewis oesophago-gastrectomy. The median transfusion requirements were 2 (0-7) units for both procedures. The resection margins were free of tumour on histopathological examination in all cases of malignancy.

Morbidity and mortality rates are shown below (Tables 1, Tables 2, 3). Risk adjusted morbidity and mortality rates were calculated using the physiological and operative scoring system for enumeration of morbidity and mortality (POSSUM) and Portsmouth POSSUM (P-POSSUM) models[5,6].

| Total patients (n = 15) | POSSUM prediction | P-POSSUM prediction | |

| Morbidity | 5 (33) | 63 | - |

| Mortality | 2 (14) | 18 | 6 |

| Total patients (n = 15) | POSSUM prediction | P-POSSUM prediction | |

| Morbidity | 6 (25) | 48 | - |

| Mortality | 1 (4) | 16 | 9 |

| Oesophagogastrectomy (n) | Total gastrectomy (n) | |

| Chest infection | 2 | 5 |

| Chylothorax | 1 | - |

| DVT/PE | 1 | 1 |

| Anastomotic leak | - | - |

| Wound sepsis | 1 | - |

Three deaths occurred, two post oesophago-gastrectomy and one post total gastrectomy. The deaths after oesophago-gastrectomy were shown at post-mortem to be due to left ventricular failure and myocardial infarction respectively. The patient who died after total gastrectomy deteriorated suddenly on the 10th post-operative day tolerated diet for three days. Symptoms, blood gases and electrocardiogram were compatible with a pulmonary embolus. Permission for a post-mortem was refused. No anastomotic leaks occurred on clinical grounds.

Anastomotic leakage following oesophago-enteric reconstruction may result in significant morbidity and mortality. The standard principles governing any gastro-intestinal anastomosis apply in dealing with the oesophagus. The anastomosis should be tension-free, well vascularized and there should be accurate mucosal apposition. Oesophageal anastomoses may be hand sewn (in one, two or even three layers) or stapled[1-4]. There is no proven advantage to either the hand sewn or stapled technique. Stapled anastomoses might be associated with a higher rate of subsequent benign stricture formation[7]. The stapled technique that is commonly used requires a purse string suture in the cut end of the proximal oesophagus to retain the head of the circular stapler. The anastomosis is completed by a single firing of the circular stapler.

It is the authors' contention that the oesophageal purse string may be a contributory factor to subsequent anastomotic related complications (leak and stricture). This is based on the observation that the distal oesophagus is stretched over the head of the circular stapler, and therefore possibly devascularized by the purse string suture. To avoid the use of a purse string, a double stapled oesophago-enteric anastomotic technique has been devised.

This paper described a novel technique of oesophago-enteric anastomosis using a double stapled technique. Whilst this was an uncontrolled study, the technique has proved reliable and to date has not resulted in any anastomotic leaks. Whilst this study cannot implicate the use of a proximal oesophageal purse string suture as a factor in anastomotic leakage, it is interesting to speculate whether the double stapled anastomosis does allow improved anastomotic healing through omission of a purse string suture. The technique described merits further evaluation either in the setting of a larger uncontrolled study or more preferably in the context of a randomised trial.

Edited by Chen WW and Zhu LH Proofread by Xu FM

| 1. | Skinner DB. Esophageal reconstruction. Am J Surg. 1980;139:810-814. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Akiyama H. Surgery for cancer of the oesophagus. Baltimore: Williams Wilkins 1990; 74-75. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Sweep RH. Thoracic surgery. Philadelphia, London: WB Saunders 1950; 256-294. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Griffin SM, Raimes SA. Upper gastrointestinal surgery. London, Philadelphia, Toronto, Sydney, Tokyo: WB Saunders 1997; 111-144. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Copeland GP, Jones D, Walters M. POSSUM: a scoring system for surgical audit. Br J Surg. 1991;78:355-360. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1126] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1087] [Article Influence: 32.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Prytherch DR, Whiteley MS, Higgins B, Weaver PC, Prout WG, Powell SJ. POSSUM and Portsmouth POSSUM for predicting mortality. Physiological and Operative Severity Score for the enUmeration of Mortality and morbidity. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1217-1220. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 486] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 485] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bardini R, Asolati M, Ruol A, Bonavina L, Baseggio S, Peracchia A. Anastomosis. World J Surg. 1994;18:373-378. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |