Published online Mar 28, 2020. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v8.i2.109

Peer-review started: November 18, 2019

First decision: December 7, 2019

Revised: February 5, 2020

Accepted: March 9, 2020

Article in press: March 9, 2020

Published online: March 28, 2020

Processing time: 162 Days and 6.1 Hours

Gastrointestinal (GI) ultrasound (GIUS) is valuable in the evaluation of GI diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, but its use in functional GI disorders (FGIDs) is largely unknown although promising. In order to review the current knowledge on current and potential uses of GIUS in FGIDs, information was obtained via a structured literature search through PubMed, EMBASE and Google Scholar databases with a combination of MESH and keyword search terms: “ultrasound”, “functional GI disorders”, “irritable bowel syndrome”, “functional dyspepsia”, “intestinal ultrasound”, “point of care ultrasonography”, “transabdominal sonography”, “motility”, “faecal loading”, “constipation”. GIUS is currently used for various settings involving upper and lower GI tracts, including excluding organic diseases, evaluating physiology, guiding treatment options and building rapport with patients. GIUS can be potentially used to correlate mechanisms with symptoms, evaluate mechanisms behind treatment efficacy, and investigate further the origin of symptoms in real-time. In conclusion, GIUS is unique in its real-time, interactive and non-invasive nature, with the ability of evaluating several physiological mechanisms with one test, thus making it attractive in the evaluation and management of FGIDs. However, there are still limitations and concerns of operator dependence and lack of validation data for widespread implementation of GIUS in FGIDs.

Core tip: Functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorders are extremely common for every gastroenterologist. However, they are largely a heterogenous group of conditions and we do not have reliable modalities of investigational tools to evaluate origin of symptoms. GI ultrasound has increasing value for the evaluation of GI diseases. We are the first to perform a review on this topic of the utility of GI ultrasound in functional GI disorders. Our results show that though the potential uses are promising, more validation data is needed for widespread implementation.

- Citation: Ong AML. Utility of gastrointestinal ultrasound in functional gastrointestinal disorders: A narrative review. World J Meta-Anal 2020; 8(2): 109-118

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v8/i2/109.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v8.i2.109

Gastrointestinal (GI) ultrasound (GIUS) is increasingly recognised as a valuable tool in the evaluation of GI disease[1], especially in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) where it has a similar diagnostic yield to endoscopy and cross-sectional imaging[2].

Functional GI disorders (FGIDs) are disorders of gut-brain interaction related to mechanisms such as motility disturbances, visceral hypersensitivity and altered central nervous system processing[3]. Their diagnoses rest on symptom-based criterias and exclusion of organic diseases. Although it is suggested that physicians make a positive diagnosis of FGID and minimize investigations[4], many perform a limited set of tests, with normal endoscopies often being the “confirmation” of a FGID[5]. GIUS have been recommended by some society guidelines to rule out organic diseases before diagnosing a FGID[6,7]. As such, the primary goal of this review is to discuss the current and potential utility of GIUS in the evaluation of FGID, focusing on common FGIDs such as IBS and functional dyspepsia (FD). As part of the review, we will discuss how clinicians can take advantage of the unique nature of GIUS to evaluate upper and lower GI physiology, exclude organic disease, guide treatment decisions and build rapport with patients.

A literature search was conducted using Medline (1946 to February 2019), EMBASE (1947 to February 2019) and Google Scholar databases using a combination of MESH and keyword search terms: “ultrasound”, “functional GI disorders”, “irritable bowel syndrome”, “functional dyspepsia”, “intestinal ultrasound”, “point of care ultrasonography”, “transabdominal sonography”, “motility”, “faecal loading” and “constipation”. Papers not written in English were excluded.

The GI tract is a unique system, with many organs performing multiple different functions. Thus, it is challenging to thoroughly assess GI function using currently available imaging techniques, which mainly evaluate anatomical structures. GIUS allows real-time evaluation of organ function, in addition to structure, and can provide a wide array of information on physiology such as motility, biomechanics, flow, and organ filling/emptying[8].

For example, GIUS allows real-time dynamic assessment of intestinal peristalsis to narrow down possible differential diagnoses as diminished peristalsis can indicate an unhealthy bowel seen in small bowel inflammation, obstruction, ischemia, and infiltrative processes[9]. If a transition point with a collapsed distal bowel is also seen, this may suggest mechanical obstruction[10]. Certain patterns can be seen in malabsorptive conditions like coeliac disease, where small bowel wall thickening is seen with hyperperistalsis causing a constant to-and-fro movement of luminal content[11].

FD is a common FGID with many putative pathophysiological mechanisms including antral hypomotility, antroduodenal dyscoordination, impaired accommodation, delayed gastric emptying and gastric hypersensitivity, each of which could contribute to the various subtypes[12,13]. It is important to consider the contributing pathophysiology to symptoms in each patient[13] as newer treatment options are available to target specific pathophysiological disturbances[12]. GIUS offers the benefit of evaluating more than one mechanism in a single test.

GIUS has been used to evaluate gastric emptying for more than 30 years[14] and has been shown to have good correlation to the “gold standard”[15] of gastric emptying measurement: Scintigraphy, with the benefit of no exposure to ionising radiation. GIUS has shown good reliability and interobserver agreement in the measurement of gastric emptying rates[16], and is cheaper and more easily repeatable compared to other modalities such as wireless motility capsules, gastric emptying breath tests and MRI[17]. This process of gastric emptying is complex and affected by many factors such as antral contractions, antroduodenal coordination, proximal gastric relaxation and pyloric tone[18], but most investigational modalities look at only a single aspect of gastric emptying[19]. GIUS overcomes this by providing real-time information on multiple parts of gastric physiology[20]. For example, GIUS can demonstrate gastric contractions and measure the frequency and amplitude of these contractions[21,22], thus investigators can visualise whether delayed gastric emptying is due to an abnormally intense pyloric contractility or antral hypomotility[23], as treatment options may differ depending on the finding[24]. GIUS can also assess the stomach’s ability to accommodate after meals[25], which is another mechanism contributing to FD symptoms, with dyspeptic patients showing smaller proximal stomach volumes after meals[26,27].

Differentiating between FGID and organic diseases can sometimes be difficult. One of the competing diagnoses for IBS is IBD which may also affect a similar demographic profile of patients[28]. It is particularly important for a timely diagnosis of IBD to be made, as delay in treatment can result in the development of complications. Laboratory markers such as C-reactive protein and faecal calprotectin are not always accurate predictors of inflammation[29,30]. Colonoscopy and cross-sectional imaging modalities have been longstanding stalwarts of the diagnostic armamentarium for IBD. However, colonoscopy is invasive and requires bowel preparation and sedation, CT imaging has the risks of ionising radiation, and MRI is costly and time-consuming.

GIUS has the benefit of being less costly, non-invasive and widely available, making it particularly useful in areas where healthcare resources are limited. It obviates the need for sedation, fasting or bowel preparation, making it ideal for repeated real-time use in clinics. GIUS also allows the managing clinician to perform the targeted examination, so decisions on therapy can be made in the right clinical context.

A prospective, real-world study[31] on consecutive patients presenting to a gastroenterology unit with symptoms suggestive of bowel disease, showed that the overall sensitivity and specificity of GIUS compared to radiological and endoscopic studies for bowel disorders was 85.4% and 95.4%, respectively. Another study[32] looked at 58 consecutive symptomatic patients presenting to a gastroenterology clinic and found GIUS to have an overall sensitivity and specificity of 80% and 97.8% respectively compared to endoscopy in identifying inflammatory causes of their symptoms. GIUS could differentiate IBS and IBD patients in a consecutive series of 313 patients[33] admitted to an outpatient clinic with non-specific chronic abdominal pain and bowel dysfunction with GIUS having 74% sensitivity and 98% specificity in detecting IBD compared to radiological and endoscopic studies. These studies suggest that GIUS can serve as a useful tool in differentiating IBD from FGID. Furthermore, GIUS can be used to triage patients and decide the urgency of investigations. GIUS can help support timing and urgency of endoscopy, as a negative GIUS together with a normal CRP and faecal calprotectin makes IBD very unlikely and therefore further investigations unnecessary[32,33]. Furthermore, the cases missed by GIUS were mild endoscopically, and often did not need urgent treatment[32,33]. In addition, they could be followed with serial GIUS scans to determine when treatment was warranted.

FGIDs also commonly result in severe abdominal pain requiring hospital admission, and emergency physicians not familiar with the patient’s background may subject them to excessive investigations. GIUS scans have been suggested as first-line imaging tools in patients with an acute abdomen[34], and have been shown to be comparable to CT scans in the diagnosis of appendicitis[35], diverticulitis[34] and intestinal obstruction[10]. The ability of GIUS to evaluate both upper and lower GI tracts, as well as intestinal and extra-intestinal features makes it a valuable initial tool when the cause of patient’s symptoms is not entirely clear. Furthermore, GIUS is able to visualise splanchnic vessels, mesentery, omentum and lymph nodes, and abnormalities in these areas lend weight to certain diagnoses[36]. GIUS can also be extended to evaluate other organs to include differentials such as ascites, ruptured ectopic pregnancies[37], nephrolithiasis[38] and gallstones[39].

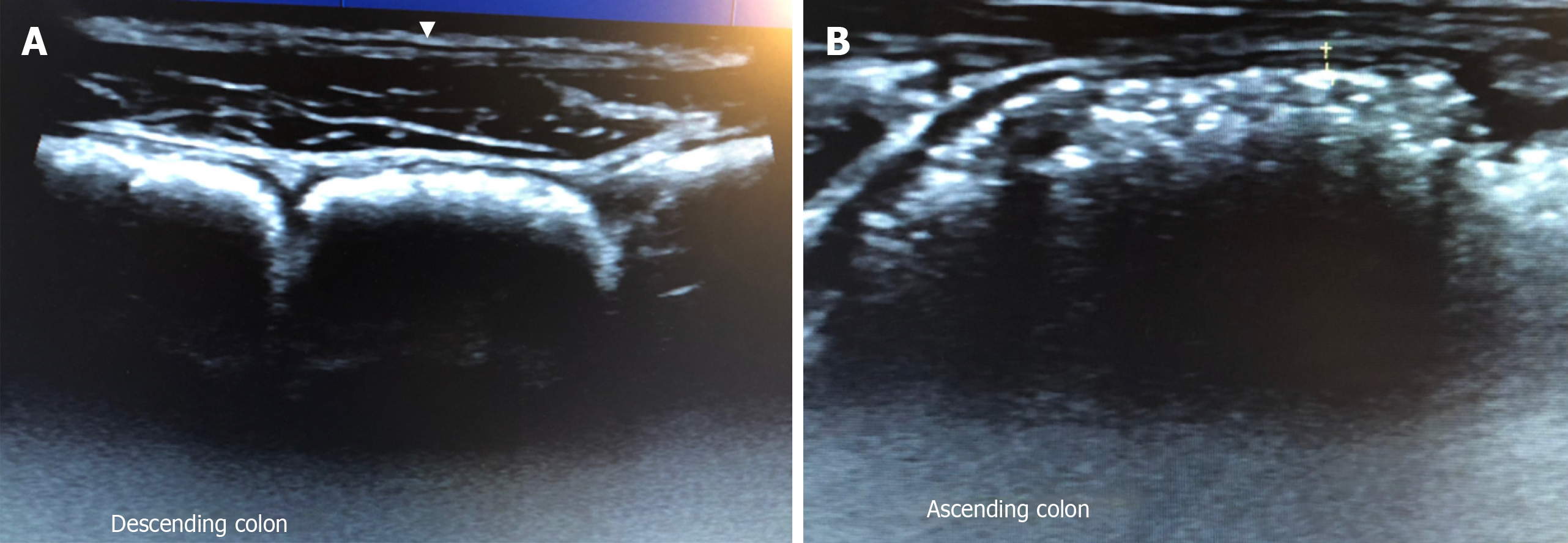

The diagnosis of FGID is centred solely on the patient history, but there are disparities between patient reported bowel habits and objective features of constipation or diarrhoea[40,41]. GIUS can objectively demonstrate constipation can help subtype IBS and educate patients, while the visualisation of the location of the faecal retention can aid the physician in choosing the appropriate treatment (Figure 1). Scoring systems[42] have been developed to report the severity of faecal loading on radiological images, by looking at the degree of faecal retention and bowel dilatation. Since GIUS has been shown to be comparable to CT scans in the visualisation of faecal loading[43], it can quantify faecal loading without exposing the patient to radiation. The severity of faecal loading can be determined on GIUS[44], with haustra-shaped acoustic reflections suggestive of “harder” faecal loading (Figure 1A), while has shown that a composite measurement of colonic diameters has been shown to be a surrogate measure of constipation[45].

There is also the potential for novel metrics to assess bowel contents. To date, MRI has been used to evaluate differences in small and large bowel content between healthy controls and patients[46], and a constricted small bowel was more commonly found in non-constipated IBS while a dilated transverse colon was more likely in IBS-C[47]. GIUS can potentially subtype IBS patients via these measurements, while offering the added benefits of being cheaper and more widely available.

There is also interest in using GIUS to assess colonic transit time which is recommended to be evaluated in chronic constipation[48]. At present transit time is measured either radiologically, via a nuclear medical study, or via wireless motility capsule which is expensive and not widely available. GIUS has been used to evaluate colonic transit time using water-filled latex balloons containing metal particles, and then following the metal particles through the stomach, small bowel and colon. In summary, GIUS has the potential to measure faecal loading, colonic diameter, and transit time in a single test.

GIUS plays a unique role in FGID patients by helping to strengthen the physician-patient relationship through several ways. IBS patients’ have been shown[49] to yearn for (1) increased quality time spent with their healthcare provider; (2) education on their condition; and (3) reassurance that organic diseases were excluded. Since GIUS does not involve sedation, physicians can use the time during the procedure to build rapport with patients by involving them in the discussion of their condition. GIUS was shown[32] to improve patient’s understanding of their condition and was generally preferred over endoscopy.

In a study by patients attending the emergency department were randomised to bedside ultrasound or standard clinical examination[50], and higher patient self-rated satisfaction score was found in the ultrasound group with decreased short-term health care consumption. Other studies have found similar results[51,52]. It has also been shown that serial imaging using ultrasound can strengthen doctor-patient relationships[53], which is a cornerstone in the management of FGID patients[3], where cognitive processes such as symptom-specific anxiety[54] may perpetuate symptoms. For example, GIUS can be used to evaluate the painful area, and then patients can be shown the images and reassured that no abnormality was detected. Subsequently, education and discussions with regard to visceral hypersensitivity can commence. Alternatively, demonstrating faecal loading can educate and convince patients of the origin of their symptoms, and pave the way to understanding treatment options.

Physicians have often been encouraged to make a positive diagnosis of FGID[55], however, the lack of biomarkers and the concern that organic causes are missed resonate with both patients and health care providers[56], further contributing to health seeking behaviour[57,58]. Using GIUS as an extension of the clinician’s physical examination has been shown[39] to reduce unnecessary investigations. In their study of 1962 consecutive patients, GIUS ruled in or out diagnostic hypotheses in about two-thirds of the cases, and further testing was only required in around 37% of patients.

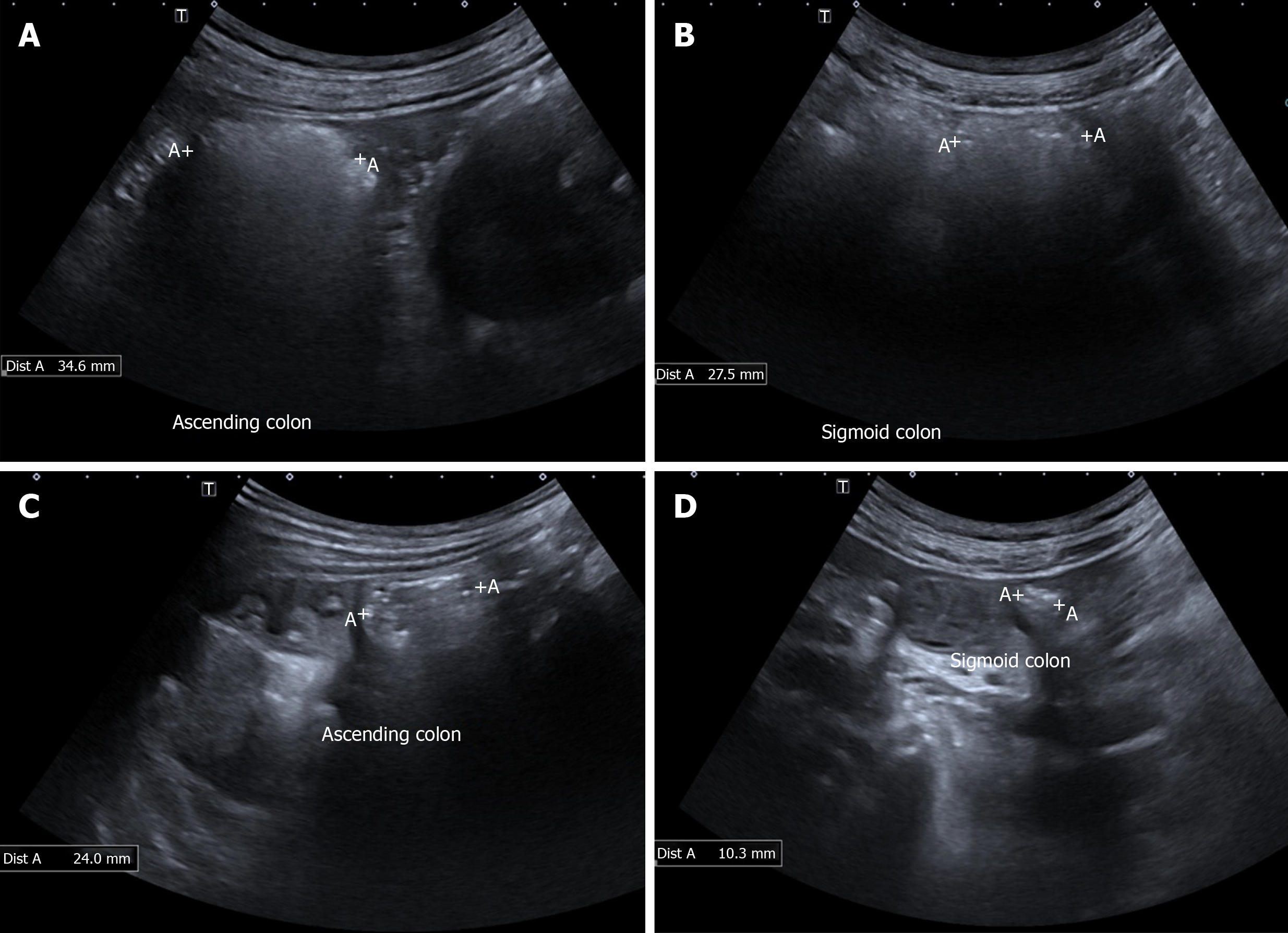

GIUS can determine the respective contributions of physiological findings in the GI tract to the patient’s overall symptoms by directly correlating the symptoms to these findings since the imaging is real time[59]. It can analyse temporal mechanistic relations of the GI tract with medications, meals[22,59] and even stress[60], and thus is a valuable tool for research in the field of GI motility. Also, one of the major challenges in assessing treatment outcomes in patients FGID is the lack of objective biomarkers, as symptoms often show wide variability[61]. Measurement of GIUS parameters can be safely and easily taken pre- and post- treatment intervention (Figure 2) to evaluate the efficacy and mode of action in real time.

An interesting use of GIUS is the evaluation of symptoms in FGID related to food intake. GIUS allows limited evaluation of the volume and content of the intestines, thus it can be used together with a food challenge to evaluate mechanisms for symptom generation. It has been shown that different types of FODMAPs generate different physiological effects on MRI scans[62]. In theory, GIUS has the potential to perform some of the MRI measurements such as colonic diameter and content, and thus can be used to correlate patient’s symptoms after a substrate load, allowing greater understanding of the origin of symptoms after ingestion of certain foodstuffs, and also diagnose malabsorptive conditions such as lactose or fructose malabsorption. To demonstrate this, 32 patients with chronic abdominal complaints self-attributed to food intake were examined with GIUS after ingesting the suspected food item. The sonographic features were recorded before, during and after the food challenge, and the investigators found significant correlation between symptoms and intestinal wall thickness in the duodenal bulb and jejunum[63].

GIUS still does have its limitations. Not all patients are easy to evaluate using GIUS: obese patients and those with previous abdominal surgery are particularly challenging. Not all areas of the bowel are seen easily with GIUS and this may be result in over-diagnosis of pathology detected in sigmoid and terminal ileum areas, with missed pathologies in the transverse colon and rectum. Furthermore, although many studies mentioned in this review demonstrate the utility of GIUS in understanding pathophysiological mechanisms contributing to a patient’s GI symptoms, these measurements have not gained clinical relevance[19], and future studies are needed to look into GIUS measurements that may predict a worse prognosis or a response to specific treatment options.

There may be resistance to the widespread adoption of GIUS because of concern of operator ability and thus the potential to miss an important diagnosis. However, there is a slow gain in acceptance that physicians can perform focused ultrasound examinations even without previous ultrasound experience[64]. It has been shown that even ultrasound-naïve clinicians can become competent after performing around 200 supervised examinations[65]. There is also a shift in perspective from a concern about missed findings to recognition that appropriate use of GIUS improves diagnostic accuracy compared to clinical examination alone[66].

FGID are extremely common conditions seen in gastroenterology practices worldwide, and we have described the current and potential uses of GIUS in the evaluation and management of FGID (Table 1). GIUS is unique in being able to offer real-time physiological information, reliably exclude organic diseases, aid the physician in guiding treatment decisions, and also strengthen patient-physician relationships, thus it offers great potential in its use in FGID (Table 2).

| Current | Potential |

| Evaluating physiology | |

| Stomach | |

| Assess contribution of mechanisms to symptoms. Mechanisms include gastric emptying, gastric motility, gastroduodenal flow, gastric wall deformation, gastric accommodation and intragastric distribution of meals | Tailor management of patients based on contributing pathophysiology of symptoms to FGID (e.g. prokinetics for patients with FD and antral hypomotility) |

| Small bowel | |

| Assess peristalsis to evaluate small bowel obstruction and its causes (e.g. mechanical vs ileus); support diagnosis for malabsorptive conditions (e.g. coeliac disease) | Study interactions of mechanisms to one another and temporal relationships between mechanisms and food/treatment/stress. e.g. evaluate mechanism behind food intolerances/malabsorption by evaluating physiological changes with food challenges in real time |

| Large bowel | |

| Objectively assess constipation/faecal loading severity and location; assess colonic transit time | Objectively assess treatment outcomes (e.g. quantify improvement in constipation post treatment); scoring systems to quantify severity of faecal loading; objectively subtype IBS patients using luminal contents and diameters of large and small bowel; potentially measure colonic transit time, evaluate colonic contents and measure bowel diameters in a single test |

| Excluding organic diseases | |

| Reliably exclude IBD from FGID in combination with other biomarkers; Useful screening investigation for abdominal pain, including acute cases as able to exclude appendicitis, diverticulitis, intestinal obstruction et al; UMAT can be used as an initial workup tool for patients with dyspepsia; Determine urgency of endoscopy based on GIUS findings; Determine type of investigations (upper vs lower GI tract, endoscopy vs cross sectional imaging) based on GIUS findings | |

| Building rapport with patients | |

| Allows more interaction time between physician and patients, opportunity to educate patients and opportunity to provide real-time reassurance | |

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Widely available | Operator dependent |

| Relatively cheap | Not all areas of bowel equally visualised |

| Non-invasive | May be technically difficult in obese or previous surgery |

| Real-time | Expertise not widely available |

| Does not involve sedation, bowel prep or intravenous contrast agents | |

| Can assess patient in physiological state | |

| Able to assess multiple physiological mechanisms with a single test | |

| Able to visualise upper and lower gastrointestinal tract as well as intra-luminal and extra-luminal organs | |

| Builds rapport with patients as allows interaction between patient and physician | |

| Allows managing clinician to perform test, allowing test to be focused in answering pertinent clinical questions |

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Singapore

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Torres MRF, Carroccio A, Yeh HZ, Mohammed RHA, Sandhu DS, Rolle U S-Editor: Wang YQ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Bryant RV, Friedman AB, Wright EK, Taylor KM, Begun J, Maconi G, Maaser C, Novak KL, Kucharzik T, Atkinson NSS, Asthana A, Gibson PR. Gastrointestinal ultrasound in inflammatory bowel disease: an underused resource with potential paradigm-changing application. Gut. 2018;67:973-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Panés J, Bouzas R, Chaparro M, García-Sánchez V, Gisbert JP, Martínez de Guereñu B, Mendoza JL, Paredes JM, Quiroga S, Ripollés T, Rimola J. Systematic review: the use of ultrasonography, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis, assessment of activity and abdominal complications of Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:125-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 534] [Cited by in RCA: 475] [Article Influence: 33.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Drossman DA. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1366] [Cited by in RCA: 1392] [Article Influence: 154.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Ford AC, Talley NJ, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Vakil NB, Simel DL, Moayyedi P. Will the history and physical examination help establish that irritable bowel syndrome is causing this patient's lower gastrointestinal tract symptoms? JAMA. 2008;300:1793-1805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Saito YA, Schiller LR, Soffer EE, Spiegel BM, Quigley EM; Task Force on the Management of Functional Bowel Disorders. American College of Gastroenterology monograph on the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109 Suppl 1:S2-26; quiz S27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 403] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Layer P, Andresen V, Pehl C, Allescher H, Bischoff SC, Classen M, Enck P, Frieling T, Haag S, Holtmann G, Karaus M, Kathemann S, Keller J, Kuhlbusch-Zicklam R, Kruis W, Langhorst J, Matthes H, Mönnikes H, Müller-Lissner S, Musial F, Otto B, Rosenberger C, Schemann M, van der Voort I, Dathe K, Preiss JC; Deutschen Gesellschaft für Verdauungs- und Stoffwechselkrankheiten; Deutschen Gesellschaft für Neurogastroenterologie und Motilität. [Irritable bowel syndrome: German consensus guidelines on definition, pathophysiology and management]. Z Gastroenterol. 2011;49:237-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Miwa H, Kusano M, Arisawa T, Oshima T, Kato M, Joh T, Suzuki H, Tominaga K, Nakada K, Nagahara A, Futagami S, Manabe N, Inui A, Haruma K, Higuchi K, Yakabi K, Hongo M, Uemura N, Kinoshita Y, Sugano K, Shimosegawa T; Japanese Society of Gastroenterology. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for functional dyspepsia. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:125-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gilja OH. Ultrasound of the stomach--the EUROSON lecture 2006. Ultraschall Med. 2007;28:32-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Muradali D, Goldberg DR. US of gastrointestinal tract disease. Radiographics. 2015;35:50-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Schmutz GR, Benko A, Fournier L, Peron JM, Morel E, Chiche L. Small bowel obstruction: role and contribution of sonography. Eur Radiol. 1997;7:1054-1058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rettenbacher T, Hollerweger A, Macheiner P, Huber S, Gritzmann N. Adult celiac disease: US signs. Radiology. 1999;211:389-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Enck P, Azpiroz F, Boeckxstaens G, Elsenbruch S, Feinle-Bisset C, Holtmann G, Lackner JM, Ronkainen J, Schemann M, Stengel A, Tack J, Zipfel S, Talley NJ. Functional dyspepsia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Park SY, Acosta A, Camilleri M, Burton D, Harmsen WS, Fox J, Szarka LA. Gastric Motor Dysfunction in Patients With Functional Gastroduodenal Symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1689-1699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bateman DN, Whittingham TA. Measurement of gastric emptying by real-time ultrasound. Gut. 1982;23:524-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, Abell TL, Gerson L; American College of Gastroenterology. Clinical guideline: management of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:18-37; quiz 38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 824] [Cited by in RCA: 750] [Article Influence: 62.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Irvine EJ, Tougas G, Lappalainen R, Bathurst NC. Reliability and interobserver variability of ultrasonographic measurement of gastric emptying rate. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:803-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Muresan C, Surdea Blaga T, Muresan L, Dumitrascu DL. Abdominal Ultrasound for the Evaluation of Gastric Emptying Revisited. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2015;24:329-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Stevens JE, Gilja OH, Gentilcore D, Hausken T, Horowitz M, Jones KL. Measurement of gastric emptying of a high-nutrient liquid by 3D ultrasonography in diabetic gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:220-225, e113-e114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dietrich CF, Braden B. Sonographic assessments of gastrointestinal and biliary functions. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;23:353-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gilja OH, Lunding J, Hausken T, Gregersen H. Gastric accommodation assessed by ultrasonography. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2825-2829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wedmann B, Adamek RJ, Wegener M. [Ultrasound detection of gastric antrum motility--evaluating a simple semiquantitative method]. Ultraschall Med. 1995;16:124-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ahluwalia NK, Thompson DG, Mamtora H, Troncon L, Hindle J, Hollis S. Evaluation of human postprandial antral motor function using ultrasound. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:G517-G522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pasricha PJ, Parkman HP. Gastroparesis: definitions and diagnosis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2015;44:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Khoury T, Mizrahi M, Mahamid M, Daher S, Nadella D, Hazou W, Benson A, Massarwa M, Sbeit W. State of the art review with literature summary on gastric peroral endoscopic pyloromyotomy for gastroparesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33:1829-1833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gilja OH, Hausken T, Odegaard S, Berstad A. Monitoring postprandial size of the proximal stomach by ultrasonography. J Ultrasound Med. 1995;14:81-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gilja OH, Hausken T, Wilhelmsen I, Berstad A. Impaired accommodation of proximal stomach to a meal in functional dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:689-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kindt S, Tack J. Impaired gastric accommodation and its role in dyspepsia. Gut. 2006;55:1685-1691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Halpin SJ, Ford AC. Prevalence of symptoms meeting criteria for irritable bowel syndrome in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1474-1482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 483] [Cited by in RCA: 456] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gecse KB, Brandse JF, van Wilpe S, Löwenberg M, Ponsioen C, van den Brink G, D'Haens G. Impact of disease location on fecal calprotectin levels in Crohn's disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:841-847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Menees SB, Powell C, Kurlander J, Goel A, Chey WD. A meta-analysis of the utility of C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, fecal calprotectin, and fecal lactoferrin to exclude inflammatory bowel disease in adults with IBS. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:444-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Parente F, Greco S, Molteni M, Cucino C, Maconi G, Sampietro GM, Danelli PG, Cristaldi M, Bianco R, Gallus S, Bianchi Porro G. Role of early ultrasound in detecting inflammatory intestinal disorders and identifying their anatomical location within the bowel. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:1009-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Novak KL, Jacob D, Kaplan GG, Boyce E, Ghosh S, Ma I, Lu C, Wilson S, Panaccione R. Point of Care Ultrasound Accurately Distinguishes Inflammatory from Noninflammatory Disease in Patients Presenting with Abdominal Pain and Diarrhea. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2016:4023065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Astegiano M, Bresso F, Cammarota T, Sarno A, Robotti D, Demarchi B, Sostegni R, Macchiarella V, Pera A, Rizzetto M. Abdominal pain and bowel dysfunction: diagnostic role of intestinal ultrasound. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:927-931. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Laméris W, van Randen A, Bipat S, Bossuyt PM, Boermeester MA, Stoker J. Graded compression ultrasonography and computed tomography in acute colonic diverticulitis: meta-analysis of test accuracy. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:2498-2511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | van Randen A, Laméris W, van Es HW, van Heesewijk HP, van Ramshorst B, Ten Hove W, Bouma WH, van Leeuwen MS, van Keulen EM, Bossuyt PM, Stoker J, Boermeester MA; OPTIMA Study Group. A comparison of the accuracy of ultrasound and computed tomography in common diagnoses causing acute abdominal pain. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:1535-1545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Nylund K, Maconi G, Hollerweger A, Ripolles T, Pallotta N, Higginson A, Serra C, Dietrich CF, Sporea I, Saftoiu A, Dirks K, Hausken T, Calabrese E, Romanini L, Maaser C, Nuernberg D, Gilja OH. EFSUMB Recommendations and Guidelines for Gastrointestinal Ultrasound. Ultraschall Med. 2017;38:273-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Sayasneh A, Preisler J, Smith A, Saso S, Naji O, Abdallah Y, Stalder C, Daemen A, Timmerman D, Bourne T. Do pocket-sized ultrasound machines have the potential to be used as a tool to triage patients in obstetrics and gynecology? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;40:145-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Smith-Bindman R, Aubin C, Bailitz J, Bengiamin RN, Camargo CA, Corbo J, Dean AJ, Goldstein RB, Griffey RT, Jay GD, Kang TL, Kriesel DR, Ma OJ, Mallin M, Manson W, Melnikow J, Miglioretti DL, Miller SK, Mills LD, Miner JR, Moghadassi M, Noble VE, Press GM, Stoller ML, Valencia VE, Wang J, Wang RC, Cummings SR. Ultrasonography versus computed tomography for suspected nephrolithiasis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1100-1110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 395] [Cited by in RCA: 417] [Article Influence: 37.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Colli A, Prati D, Fraquelli M, Segato S, Vescovi PP, Colombo F, Balduini C, Della Valle S, Casazza G. The use of a pocket-sized ultrasound device improves physical examination: results of an in- and outpatient cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Palsson OS, Baggish JS, Turner MJ, Whitehead WE. IBS patients show frequent fluctuations between loose/watery and hard/lumpy stools: implications for treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:286-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Halmos EP, Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Burgell RE, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Inaccuracy of patient-reported descriptions of and satisfaction with bowel actions in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Leech SC, McHugh K, Sullivan PB. Evaluation of a method of assessing faecal loading on plain abdominal radiographs in children. Pediatr Radiol. 1999;29:255-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Yabunaka K, Matsuo J, Hara A, Takii M, Nakagami G, Gotanda T, Nishimura G, Sanada H. Sonographic visualization of fecal loading in adults: Comparison with computed tomography. J Diagnostic Med Sonogr. 2015;31:86-92. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Yabunaka K, Nakagami G, Komagata K, Sanada H. Ultrasonographic follow-up of functional chronic constipation in adults: A report of two cases. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2017;5:2050313X17694234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Manabe N, Cremonini F, Camilleri M, Sandborn WJ, Burton DD. Effects of bisacodyl on ascending colon emptying and overall colonic transit in healthy volunteers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:930-936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Major G, Murray K, Singh G, Nowak A, Hoad CL, Marciani L, Silos-Santiago A, Kurtz CB, Johnston JM, Gowland P, Spiller R. Demonstration of differences in colonic volumes, transit, chyme consistency, and response to psyllium between healthy and constipated subjects using magnetic resonance imaging. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30:e13400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Lam C, Chaddock G, Marciani Laurea L, Costigan C, Cox E, Hoad C, Pritchard S, Gowland P, Spiller R. Distinct Abnormalities of Small Bowel and Regional Colonic Volumes in Subtypes of Irritable Bowel Syndrome Revealed by MRI. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:346-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Rao SS, Meduri K. What is necessary to diagnose constipation? Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25:127-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Halpert A, Godena E. Irritable bowel syndrome patients' perspectives on their relationships with healthcare providers. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:823-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Lindelius A, Törngren S, Nilsson L, Pettersson H, Adami J. Randomized clinical trial of bedside ultrasound among patients with abdominal pain in the emergency department: impact on patient satisfaction and health care consumption. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009;17:60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Durston W, Carl ML, Guerra W. Patient satisfaction and diagnostic accuracy with ultrasound by emergency physicians. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17:642-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Hedges JR, Trout A, Magnusson AR. Satisfied Patients Exiting the Emergency Department (SPEED) Study. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:15-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Klauser AS, Tagliafico A, Allen GM, Boutry N, Campbell R, Court-Payen M, Grainger A, Guerini H, McNally E, O'Connor PJ, Ostlere S, Petroons P, Reijnierse M, Sconfienza LM, Silvestri E, Wilson DJ, Martinoli C. Clinical indications for musculoskeletal ultrasound: a Delphi-based consensus paper of the European Society of Musculoskeletal Radiology. Eur Radiol. 2012;22:1140-1148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Van Oudenhove L, Crowell MD, Drossman DA, Halpert AD, Keefer L, Lackner JM, Murphy TB, Naliboff BD, Levy RL. Biopsychosocial Aspects of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 291] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 35.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Cash BD, Schoenfeld P, Chey WD. The utility of diagnostic tests in irritable bowel syndrome patients: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2812-2819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Lacy BE, Weiser K, Noddin L, Robertson DJ, Crowell MD, Parratt-Engstrom C, Grau MV. Irritable bowel syndrome: patients' attitudes, concerns and level of knowledge. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1329-1341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Faresjö Å, Grodzinsky E, Hallert C, Timpka T. Patients with irritable bowel syndrome are more burdened by co-morbidity and worry about serious diseases than healthy controls--eight years follow-up of IBS patients in primary care. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Howell S, Talley NJ. Does fear of serious disease predict consulting behaviour amongst patients with dyspepsia in general practice? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:881-886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Hausken T, Gilja OH, Undeland KA, Berstad A. Timing of postprandial dyspeptic symptoms and transpyloric passage of gastric contents. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:822-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Hveem K, Hausken T, Svebak S, Berstad A. Gastric antral motility in functional dyspepsia. Effect of mental stress and cisapride. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:452-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Simren M, Spiller R. Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1781] [Cited by in RCA: 1898] [Article Influence: 210.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 62. | Murray K, Wilkinson-Smith V, Hoad C, Costigan C, Cox E, Lam C, Marciani L, Gowland P, Spiller RC. Differential effects of FODMAPs (fermentable oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyols) on small and large intestinal contents in healthy subjects shown by MRI. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:110-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Arslan G, Gilja OH, Lind R, Florvaag E, Berstad A. Response to intestinal provocation monitored by transabdominal ultrasound in patients with food hypersensitivity. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:386-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Atkinson NS, Bryant RV, Dong Y, Maaser C, Kucharzik T, Maconi G, Asthana AK, Blaivas M, Goudie A, Gilja OH, Nolsøe C, Nürnberg D, Dietrich CF. WFUMB Position Paper. Learning Gastrointestinal Ultrasound: Theory and Practice. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2016;42:2732-2742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Monteleone M, Friedman A, Furfaro F, Dell’Era A, Bezzio C, Maconi G. The learning curve of intestinal ultrasonography in assessing inflammatory bowel disease – preliminary results. J Chron’s Colitis. 2013;7:S64. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Royse CF, Canty DJ, Faris J, Haji DL, Veltman M, Royse A. Core review: physician-performed ultrasound: the time has come for routine use in acute care medicine. Anesth Analg. 2012;115:1007-1028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |