Published online Dec 26, 2015. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v3.i6.232

Peer-review started: April 30, 2015

First decision: June 24, 2015

Revised: October 7, 2015

Accepted: November 3, 2015

Article in press: November 4, 2015

Published online: December 26, 2015

Processing time: 238 Days and 2.4 Hours

AIM: To assess the safety and efficacy of self-expandable metal stents (SEMSs) for malignant colorectal obstruction.

METHODS: Data regarding technical success, clinical success, and procedure related complications were collected from included studies. DerSimonian-Laird random effects model was used to generate the overall outcome. Thirty international studies with a total of 2058 patients with malignant colorectal obstruction were included.

RESULTS: The technical and clinical success rates for SEMS placement were 94% (95%CI: 92-96) and 91% (95%CI: 88-93), respectively. Overall complication rate for SEMS was 23% (95%CI: 18-29). Stent migration 8% (95%CI: 6-10) and stent obstruction 8% (95%CI: 6-11) were the most common complications, followed by perforation 5% (95%CI: 4%-7%). Surgical or endoscopic re-interventions were needed in 14% (95%CI: 10-18) of patients. Endoscopic repeat stent placement was required in 8% (95%CI: 6-10), while surgical intervention was needed in 6% (95%CI: 4-8).

CONCLUSION: SEMS are effective when used as palliation or bridge to surgery for malignant colorectal obstruction with high technical and clinical success. About 14% of patients require repeat endoscopic or surgical intervention for stent failure or to manage stent related complications.

Core tip: The technical and clinical success rates for self-expandable metal stents (SEMSs) placement were 94% (95%CI: 92-96) and 91% (95%CI: 88-93), respectively. Overall complication rate for SEMS was 23% (95%CI: 18-29). Stent migration 8% (95%CI: 6-10) and stent obstruction 8% (95%CI: 6-11) were the most common complications, followed by perforation 5% (95%CI: 4%-7%). Surgical or endoscopic re-interventions were needed in 14% (95%CI: 10-18) of patients. Endoscopic repeat stent placement was required in 8% (95%CI: 6-10), while surgical intervention was needed in 6% (95%CI: 4-8). SEMS are effective when used as palliation or bridge to surgery for malignant colorectal obstruction with high technical and clinical success. About 14% of patients require repeat endoscopic or surgical intervention for stent failure or to manage stent related complications.

- Citation: Thosani N, Banerjee S, Khanijow V, Rao B, Priyanka P, Ertan A, Guha S. Role of self-expanding metal stents in patients with malignant colorectal obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Meta-Anal 2015; 3(6): 232-253

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v3/i6/232.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v3.i6.232

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a devastating disease that impacts patients and healthcare systems significantly globally[1]. In United States, CRC is the second leading cause of cancer related mortality. In addition to early colon cancer screening, it is estimated that up to 50830 deaths will be attributed to CRC in the United States in 2013[1,2]. Approximately, 7% to 29% CRC patients presents with colon obstruction during clinical presentation[3-5]. Conventionally, these patients underwent emergency surgery (ES) with the creation of temporary or permanent colostomies to resolve symptoms. Despite an effective treatment alternative, surgery has been associated with high morbidity (32%-64%) and mortality rates (15%-34%)[4,5].

Spinelli et al[6] (1992) introduced self-expandable metal stents (SEMSs) to be used as palliative initial therapy for malignant rectal obstruction. On these lines, colonic stent placement may be used to palliate obstructive symptoms either for those patients where resection is not deemed an option, or to allow bowel preparation prior to elective surgery, popularly known as bridge to surgery (BTS). Early studies supported colonic stent placement as reduction in mortality, morbidity and required number of colostomies observed, along with its ability to prevent the need for ES in patients that have disseminated metastatic disease or critical surgical risks[7,8]. Pooled analysis by Sebastian et al[9] provided support for the placement of SEMS for neoplastic colonic obstruction, as technical and clinical success rates observed were 94% and 91% respectively. However, some studies had raised the concerns regarding safety of SEMS as high rate of long term adverse events including perforation were reported[5,10,11]. In 2007, a multicenter randomized trial that compared safety of SEMS over surgery for palliation of obstruction in stage IV left-sided CRC patient population was prematurely terminated, due to the unexpectedly high rate of perforation in the non-surgical patients[12]. In 2011, another multicenter randomized trial, assessing safety of SEMS over ES in acute left-sided malignant obstruction patient cohort was also terminated prematurely, as an interim analysis showed increased 30-d morbidity in the SEMS group with no significant increase in their mean global health status[5]. Given the significant heterogeneity with conflicting outcomes in published literature, the objective of the current study was to systematically review the safety, efficacy and overall clinical impact of SEMS in patient cohort with malignant colorectal obstruction with a comprehensive meta-analytic approach.

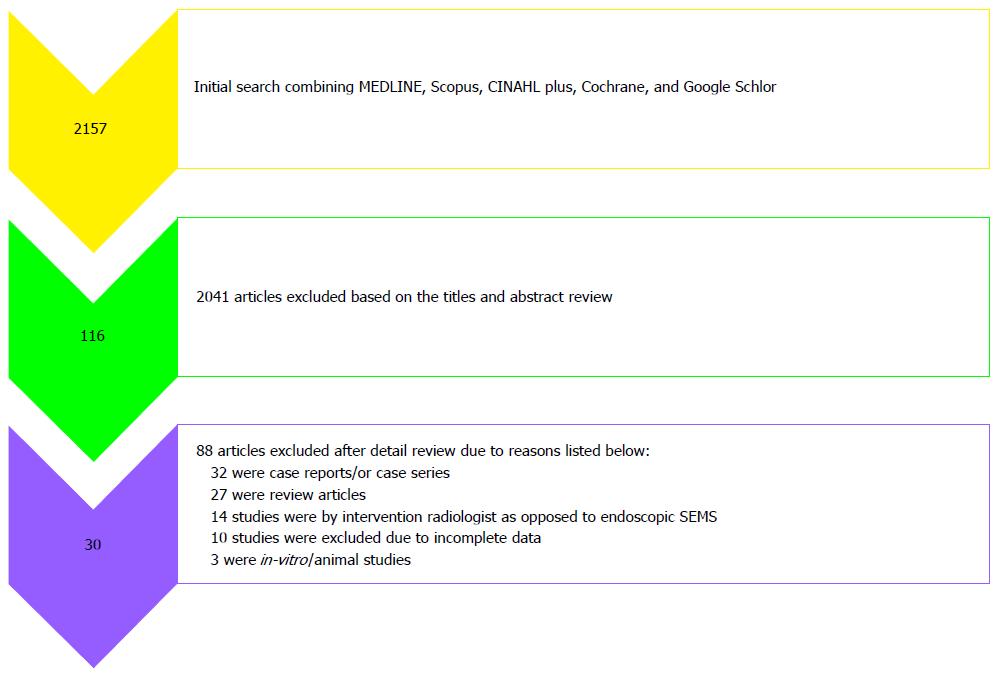

Literature search for this systematic review was performed using the established guidelines (PRISMA) for systematic review[13]. Databases such as MEDLINE [Ovid MEDLINE(R) in-process and other non-indexed citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) daily, Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Ovid OLD MEDLINE (R) 1946 to June 2013], SCOPUS (MEDLINE and EMBASE), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Google scholar, and CINAHL Plus were searched. A systematic literature search was performed by using following search terms: (1) “stent” and “CRC or colon cancer or rectal cancer or colonic obstruction or intestinal obstruction or bowel obstruction or malignant obstruction”; (2) “metal stent” and “CRC or colon cancer or rectal cancer or colonic obstruction or intestinal obstruction or bowel obstruction or malignant obstruction”; (3) SEMS and “CRC or colon cancer or rectal cancer or colonic obstruction or intestinal obstruction or bowel obstruction or malignant obstruction”; and (4) SEMS and “CRC or colon cancer or rectal cancer or colonic obstruction or intestinal obstruction or bowel obstruction or malignant obstruction”. Reference list of all the selected articles was screened to avoid exclusion of any potential article in the initial search. Literature search was limited to human subjects. Final screening to determine eligibility criteria for all the articles was performed independently by two investigators (NT and VK). All the differences were resolved by discussion with two senior investigators (MS and SG) on this study. After consensus, final report was retrieved and reviewed by the same two investigators (NT and VK).

Study population: Patients diagnosed with primary or metastatic CRC having clinical and/or radiologic signs and symptoms of malignant bowel obstruction identified as cohort for this study.

Intervention: The intervention was endoscopic SEMS placement.

Study design: Both retrospective and prospective studies who identified patients with malignant bowel obstruction and underwent endoscopic placement of SEMS for palliation or BTS were included.

Outcome: The primary outcome of the study was to evaluate endoscopically placed SEMS technique for the following parameters: Technical and clinical success rate, rate of occurrence of adverse events (perforation, stent migration, and obstruction) and rate of need for re-interventions (surgical, endoscopic re-stenting, and other endoscopic interventions).

Case reports, case series and studies with insufficient data were excluded. The studies where stents placement was non-endoscopic by intervention radiologists were also excluded from the analysis.

Data was abstracted by two independent investigators (NT and VK) from the studies that met eligibility criteria. All the following extracted data was placed on standardized forms (Microsoft Excel, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Wash): (1) Study characteristics: study design, setting and criteria, country, year of publication, sample size, clinical context; (2) Demographics: age (mean), male and female patient proportion; and (3) Interventions: SEMS type and manufacture.

Outcomes: Technical and clinical success, complication, re-intervention rate.

Assessment of study quality and risk of bias was performed as per guidelines established by Cochrane handbook[14]. Methods included were randomization schedule, conceal allocation, whether blinding was implemented, what proportion of patients completed follow-up, whether an intention-to-treat analysis was extractable, and whether there was evidence of selective reporting of outcomes. Two authors (NT and BR) evaluated independently and conflicting issues were resolved after discussion with senior investigators (SG).

For the purpose of this meta-analysis, the technical success was defined as accurate endoscopic SEMS deployment, with adequate stricture coverage without any immediate procedure related adverse event. Decompression and relief of obstructive symptoms within 72 h of SEMS placement without any adverse events was identified as clinical success. Obstruction was defined as obstruction due to tumor ingrowth, tumor overgrowth and fecal impaction requiring intervention. Other adverse events assessed include perforation, migration, bleeding, tenesmus and any other related symptoms. Re-intervention was defined as surgical or endoscopic procedures done due to technical failure, clinical failure or adverse events.

DerSimonian-Laird random effects model was used to pool the data across the studies and to obtain overall estimates (in percentages) and the 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Robustness of the random-effects model is more than the fixed effects model as it incorporates weighing scheme both within and between-study variations[15]. Further subgroup analysis was performed for (1) indication of SEMS placement (palliation vs BTS); (2) prospective vs retrospective studies; (3) single center vs multicenter studies; and (4) geographical location (i.e., North America, Europe, and Asia).

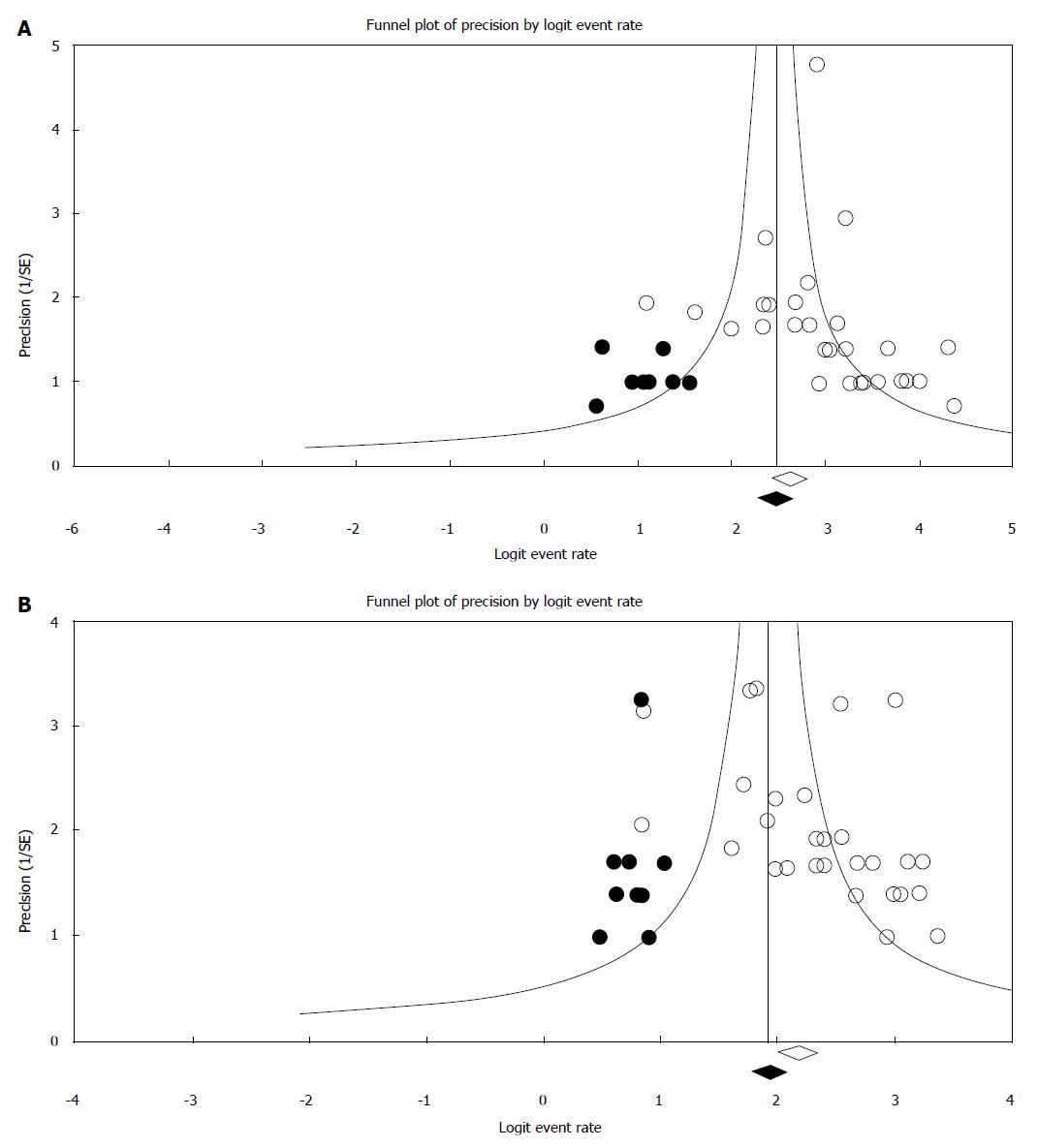

Cochran Q statistic was used to assess statistical heterogeneity with and between studies and further quantified using I2 statistics[16]. We arbitrarily defined I2 values of 25%, 50% and 75% for low, moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively and were generally used for descriptive purposes only[17]. To determine each study influence on pooled OR, removal of each study was done at a time in the meta-analysis during sensitivity analysis. Tools like Egger regression asymmetry test[18], Fail-safe N tests, and the trim-and-fill method[19] were used to assess the robustness of the meta-analysis for the publication bias. To further evaluate publication bias using the standard error and diagnostic odds ratio Funnel plot was constructed[20,21]. All statistical tests were performed with the Comprehensive Meta-analysis version 2.0 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ). A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for this meta-analysis. Statistical review of the study has been performed by an experienced biomedical statistician.

Figure 1 depicts the study selection process. Thirteen studies from Europe[5,10,22-32], 12 studies from Asia[7,33-43], 3 studies from North America[11,44,45] and 1 study each from Australia[8] and Africa[46] were included. There were 8 prospective studies[22-24,27,31,33,36-38] 17 retrospective studies[7,8,10,11,25,26,28-30,32,34,35,39,40,42,44,45], 4 randomized control trials (RCTs)[5,41,43,46] and one combined retrospective and prospective study[24]. Another RCT by Pirlet et al[47] was excluded from the meta analysis as approximately half of the SEMS in this study were placed by an interventional radiologist non endoscopically. In total, 2058 patients with malignant CRC obstruction were treated with endoscopic SEMS placement: 1313 for palliation and 745 as BTS. The study characteristics for all the included studies are shown in Table 1. The results regarding assessment for risk and bias and overall study quality are shown in Figure 2.

| Ref. | Study design | SEMS | Total | ||

| Palliation | BTS | ||||

| Palliation | |||||

| 1 | Ptok[23]-2006-Germany | Prospective, Single Center | 48 | 0 | 48 |

| 2 | Repici[22]-2007-Europe | Prospective, Multicenter | 44 | 0 | 44 |

| 3 | Im[33]-2008-South Korea | Prospective, Single Center | 49 | 0 | 49 |

| 4 | Suh[34]-2010-South Korea | Retrospective, Single Center | 55 | 0 | 55 |

| 5 | Jung[35]-2010-South Korea | Retrospective, Single Center | 39 | 0 | 39 |

| BTS | |||||

| 6 | Fregonese[24]-2008-United Kingdom | Prospective and Retrospective, Multicenter | 0 | 36 | 36 |

| 7 | Li[36]-2010-China | Prospective, Single Center | 0 | 52 | 52 |

| Palliation and BTS | |||||

| 8 | Meisner[25]-2004-Denmark | Retrospective, Single Center | 51 | 38 | 89 |

| 9 | Soto[26]-2006-Spain | Retrospective, Single Center | 36 | 22 | 58 |

| 10 | Lee[37]-2007-South Korea | Prospective, Single Center | 37 | 43 | 80 |

| 11 | Repici[27]-2008-Europe | Prospective, Multicenter | 23 | 19 | 42 |

| 12 | Stipa[28]-2008- Italy | Retrospective, Single Center | 9 | 22 | 31 |

| 13 | Branger[29]-2010-France | Retrospective, Single Center | 66 | 27 | 93 |

| 14 | Fernandez-Esparrach[10]-2010-Spain | Retrospective, Single Center | 38 | 9 | 47 |

| 15 | Lee[44]-2010-United States | Retrospective, Single Center | 41 | 5 | 46 |

| 16 | Park[38]-2010-South Korea | Prospective, Single Center | 107 | 44 | 151 |

| 17 | Small[11]-2010-United States | Retrospective, Single Center | 168 | 65 | 233 |

| 18 | West[30]-2010-United Kingdom | Retrospective, Multicenter | 21 | 6 | 27 |

| 19 | Meisner[31]-2011-Denmark | Prospective, Multicenter | 257 | 182 | 439 |

| Palliative SEMS vs palliative surgery | |||||

| 20 | Law[7]-2003-China | Retrospective, Single Center | 30 | 0 | 61 |

| 21 | Carne[8]-2004-New Zealand | Retrospective, Single Center | 25 | 0 | 44 |

| 22 | Suarez[32]-2009-Spain | Retrospective, Single Center | 45 | 0 | 98 |

| 23 | Vemulapalli[45]-2009-United States | Retrospective, Single Center | 53 | 0 | 123 |

| 24 | Lee[39]-2011-South Korea | Retrospective, Single Center | 71 | 0 | 144 |

| SEMS as BTS vs emergency surgery | |||||

| 25 | Ng[40]-2006-Hong Kong | Retrospective, Single Center | 0 | 20 | 60 |

| 26 | Cheung[41]-2009-China | Randomized Controlled Trial, Single Center | 0 | 24 | 48 |

| 27 | Guo[42]-2011-China | Retrospective, Single Center | 0 | 34 | 92 |

| 28 | vanHooft[5]-2011-The Netherlands | Randomized Controlled Trial, Multicenter | 0 | 47 | 98 |

| 29 | Ho[43]-2011-Singapore | Randomized Controlled Trial, Single Center | 0 | 20 | 39 |

| 30 | Abdel-Hamid[46]-2013-Egypt | Randomized Controlled Trial, Single Center | 0 | 30 | 60 |

| Total | 1313 | 745 | 2058 | ||

Multiple types of stents were used in these studies including Enteral Wallstent[5,7,8,10,11,23-26,29,40,41,44,45] (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA), uncovered esophageal Wallstent[7] (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA), Ultraflex Precision colonic stent[7,11,22,24,25,44] (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA), Polyflex esophageal stent[44] (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA), Wallflex colonic stent[5,10,11,27,31,35,38,39,44,45] (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA), Choo-stent[7,23,25] (M.I. Tech Co, Ltd, Seoul, South Korea), Memotherm-Stent[23,25] (Bard, Germany), Colonic Z-Stent[25] (Cook Medical, Inc., Bloomington, IN), EsophaCoili[25] (Medtronic/Instent, Eden Prairie, MN), Microtech[8,36] (Nanjing Microinvasive Co, China), Hanarostent[10,29,32-35] (M.I.Tech Co, Seoul, South Korea), Niti-S colonic covered[35,37] (Taewoong Medical Co, Seoul, South Korea), Niti-S Colonic uncovered stent[37,39] (Taewoong Medical Co, Seoul, South Korea) and Comvi stent[38,39] (Taewoong Medical Co, Gimpo, South Korea).

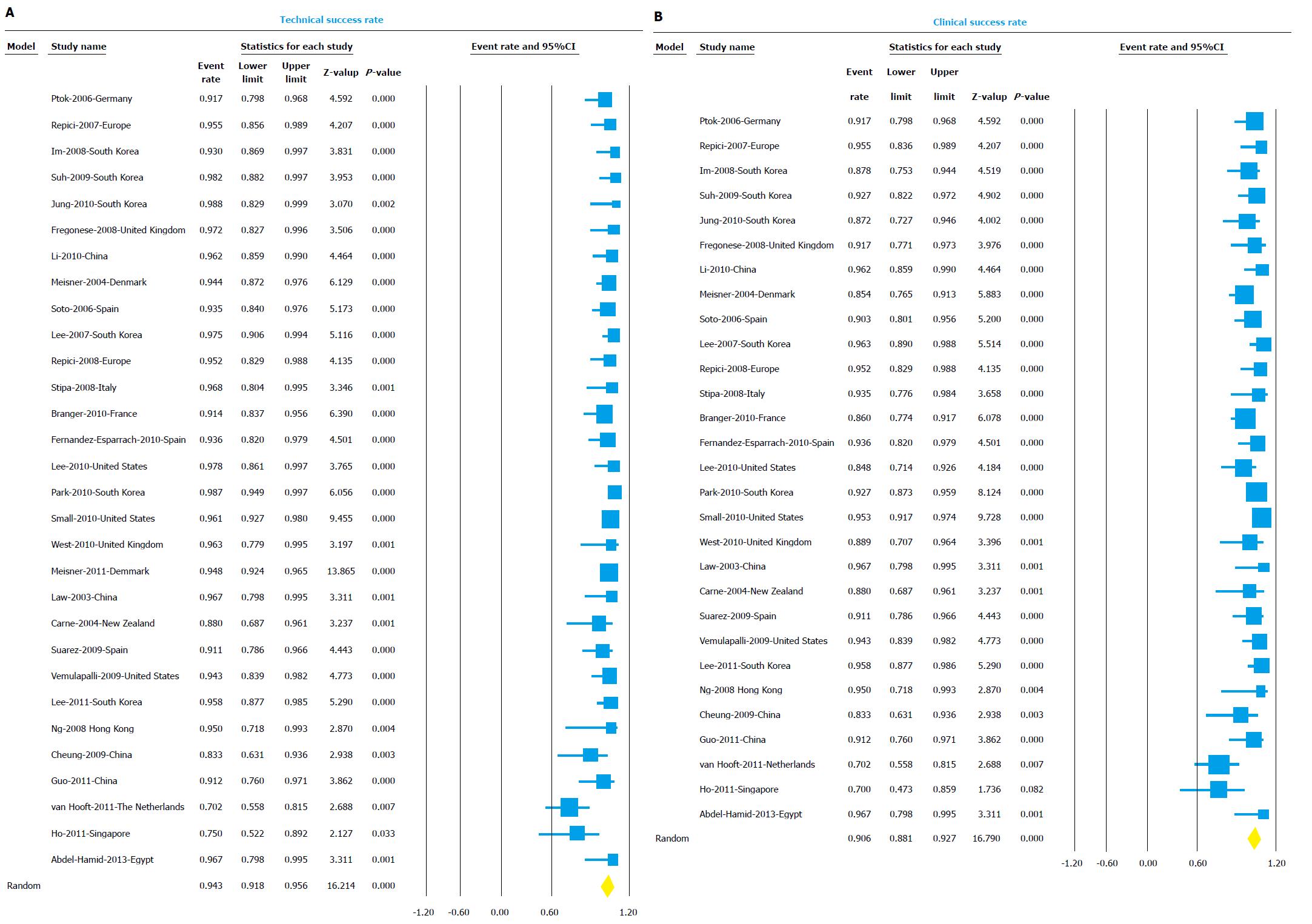

Technical and clinical success: Thirty studies reported technical success and were included in the analysis. Overall technical success rate was 94% (95%CI: 91.8-95.6) (Figure 3A). The I2 value for heterogeneity analysis was 58. The technical success rate in the palliation group (10 studies) was 94.2% (95%CI: 91.3-96.1) and in the BTS group (8 studies) was 89.4% (95%CI: 79.5-94.8).

Twenty-nine studies reported clinical success and were included in the analysis. Overall clinical success rate was 90.6% (95%CI: 88.1-92.7) (Figure 3B). The I2 value for heterogeneity analysis was 51. The clinical success rate in the palliation group (10 studies) was 91.7% (95%CI: 88.7-94) and in the BTS group (8 studies) was 87.9% (95%CI: 78.1-93.7). The results of the subgroup analysis for both technical and clinical success based on indication, center, design, and region are shown in detail in Table 2.

| Category and subgroups | Studies | Event rate (%) | 95%CI | P value | I2 value | |

| Technical success | 30 | 94.0 | 91.8-95.6 | 0.000 | 58.07 | |

| Indication | Palliation | 10 | 94.2 | 91.3-96.1 | 0.580 | 0.00 |

| BTS | 8 | 89.4 | 79.5-94.8 | 0.003 | 67.14 | |

| Center | Single Center | 24 | 94.1 | 92.1-95.6 | 0.06 | 32.74 |

| Multicenter | 6 | 93.3 | 83.1-97.5 | 0.000 | 84.70 | |

| Design | Prospective | 11 | 93.1 | 86.9-96.5 | 0.000 | 80.94 |

| Retrospective | 18 | 94.4 | 92.7-95.7 | 0.846 | 0.00 | |

| Region | Asia | 12 | 95.2 | 91.0-97.5 | 0.005 | 58.82 |

| Europe | 13 | 92.8 | 89-95.4 | 0.001 | 65.40 | |

| North America | 3 | 96.0 | 93.2-97.6 | 0.679 | 0.00 | |

| Clinical success | 29 | 90.6 | 88.1-92.7 | 0.001 | 50.58 | |

| Indication | Palliation | 10 | 91.7 | 88.7-94 | 0.719 | 0.00 |

| BTS | 8 | 87.9 | 78.1-93.7 | 0.004 | 66.35 | |

| Center | Single Center | 23 | 90.8 | 88.4-92.7 | 0.042 | 36.52 |

| Multicenter | 5 | 89.7 | 76.7-95.9 | 0.004 | 73.93 | |

| Design | Prospective | 10 | 89.7 | 82.6-94.0 | 0.001 | 72.48 |

| Retrospective | 18 | 91.0 | 88.7-92.3 | 0.238 | 18.04 | |

| Region | Asia | 12 | 91.2 | 87.2-94.1 | 0.044 | 45.37 |

| Europe | 12 | 89.1 | 84.5-92.3 | 0.029 | 48.73 | |

| North America | 3 | 92.5 | 83.9-96.7 | 0.040 | 69.03 | |

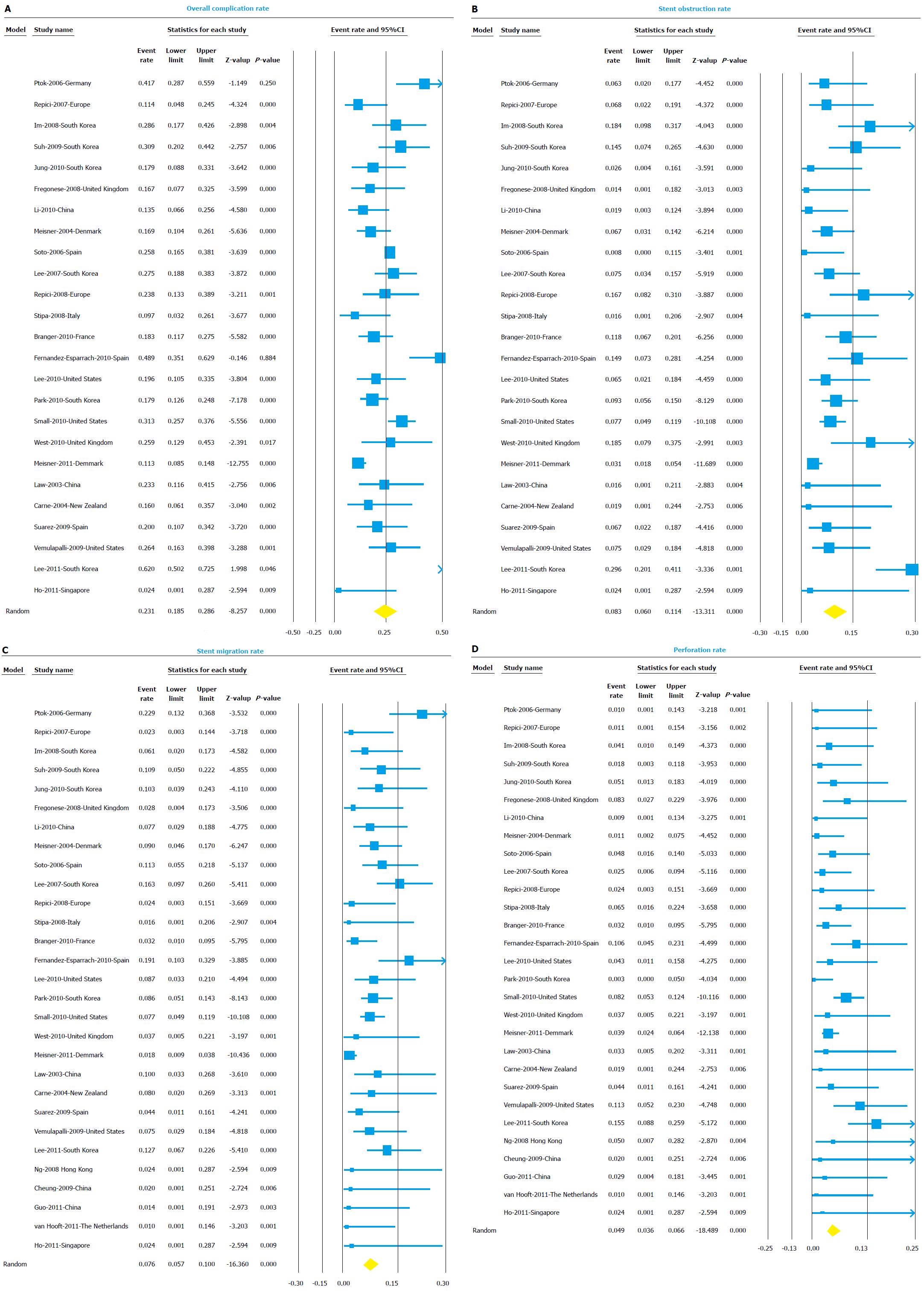

The overall complication rate included complications like perforation, migration, and stent obstruction and any other reported complication like stent related bleeding, tenesmus, etc. Twenty five studies reported all complications in detail and were included in the analysis of overall complication rate. The overall complication rate was 23.1% (95%CI: 18.5-28.6) (Figure 4A). The I2 value for heterogeneity analysis was 82. The complication rate was higher for palliation group (27.3%, 95%CI: 18.7-38) compared to BTS group (13.8%, 95%CI: 8.3-22.2).

Stent occlusion due to tumor ingrowth, overgrowth or fecal impaction was the most common complication with overall stent occlusion rate of 8.3% (95%CI: 6.0-11.4) (Figure 4B). Stent occlusion was most likely function of tumor growth and disease progression over time, as for palliation group stent occlusion rate was 9.5% (95%CI: 5.4-16.4) compared to only 1.9% (95%CI: 0.5-7.1) for BTS group.

Stent migration was seen in 7.6% (95%CI: 5.7-10.0) of cases (Figure 4C). Once again, stent migration was more frequently seen in palliation group (10.2%, 95%CI: 7.1-14.5) compared to BTS group (4.1%, 95%CI: 2.0-8.1).

Perforation was seen in 4.9% (95%CI: 3.6-6.6) cases (Figure 4D). Perforations being early complication after stent placement, perforation rates were similar between palliation group 5.4% (95%CI: 2.9-9.8) and BTS group 4.0% (95%CI: 1.9-8.2). The results of the subgroup analysis for all complication rates based on indication, center, design, and region are shown in detail in Table 3.

| Category and subgroups | Studies | Event rate (%) | 95%CI | P value | I2 value | |

| Overall complication rate | 25 | 23.1 | 18.5-28.6 | 0.000 | 81.86 | |

| Indication | Palliation | 10 | 27.3 | 18.7-38 | 0.000 | 80.60 |

| BTS | 3 | 13.8 | 8.3-22.2 | 0.371 | 0.00 | |

| Center | Single Center | 20 | 25.2 | 20.1-31.1 | 0.000 | 78.20 |

| Multicenter | 5 | 16.2 | 10.8-23.6 | 0.058 | 56.11 | |

| Design | Prospective | 8 | 20.6 | 13.6-30.0 | 0.000 | 82.64 |

| Retrospective | 16 | 25.0 | 19.1-31.8 | 0.000 | 79.08 | |

| Center | Asia | 9 | 25.1 | 16.1-36.9 | 0.000 | 84.93 |

| Europe | 12 | 21.3 | 15.1-29.1 | 0.000 | 81.28 | |

| North America | 3 | 28.0 | 21.9-35 | 1.000 | 0.00 | |

| Obstruction rate | 25 | 8.3 | 6.0-11.4 | 0.000 | 68.79 | |

| Indication | Palliation | 10 | 9.5 | 5.4-16.4 | 0.001 | 69.55 |

| BTS | 3 | 1.9 | 0.5-7.1 | 0.959 | 0.00 | |

| Center | Single Center | 20 | 8.7 | 6.2-12.1 | 0.000 | 63.23 |

| Multicenter | 5 | 3.1 | 1.8-5.4 | 0.000 | 80.21 | |

| Design | Prospective | 8 | 8.2 | 4.9-13.5 | 0.001 | 70.11 |

| Retrospective | 16 | 8.7 | 5.7-13.0 | 0.000 | 67.79 | |

| Region | Asia | 9 | 9.8 | 5.3-17.2 | 0.000 | 74.58 |

| Europe | 12 | 7.7 | 4.8-12.1 | 0.001 | 63.77 | |

| North America | 3 | 7.5 | 5.1-10.9 | 0.961 | 0.00 | |

| Migration rate | 29 | 7.6 | 5.7-10.0 | 0.000 | 55.48 | |

| Indication | Palliation | 10 | 10.2 | 7.1-14.5 | 0.150 | 32.56 |

| BTS | 7 | 4.1 | 2.0-8.1 | 0.687 | 0.00 | |

| Center | Single Center | 23 | 9.7 | 7.7-12.1 | 0.061 | 33.51 |

| Multicenter | 6 | 2.1 | 1.2-3.6 | 0.977 | 0.00 | |

| Design | Prospective | 10 | 5.5 | 2.6-11.3 | 0.000 | 79.25 |

| Retrospective | 18 | 9.0 | 7.3-11.1 | 0.389 | 5.55 | |

| Center | Asia | 12 | 10.2 | 7.9-13.0 | 0.434 | 0.95 |

| Europe | 13 | 5.4 | 2.9-10.0 | 0.000 | 75.80 | |

| North America | 3 | 7.8 | 5.4-11.3 | 0.972 | 0.00 | |

| Perforation rate | 29 | 4.9 | 3.6-6.6 | 0.037 | 34.39 | |

| Indication | Palliation | 10 | 5.4 | 2.9-9.8 | 0.054 | 46.00 |

| BTS | 7 | 4.0 | 1.9-8.2 | 0.646 | 0.00 | |

| Center | Single Center | 23 | 5.1 | 3.6-7.2 | 0.042 | 36.56 |

| Multicenter | 6 | 4.0 | 2.6-4.7 | 0.586 | 0.00 | |

| Design | Prospective | 10 | 3.1 | 2.1-4.7 | 0.722 | 0.00 |

| Retrospective | 18 | 6.2 | 4.4-8.6 | 0.117 | 29.48 | |

| Center | Asia | 12 | 3.6 | 1.8-7.0 | 0.024 | 50.02 |

| Europe | 13 | 4.4 | 3.2-6.0 | 0.472 | 0.00 | |

| North America | 3 | 8.4 | 5.8-11.9 | 0.463 | 0.00 | |

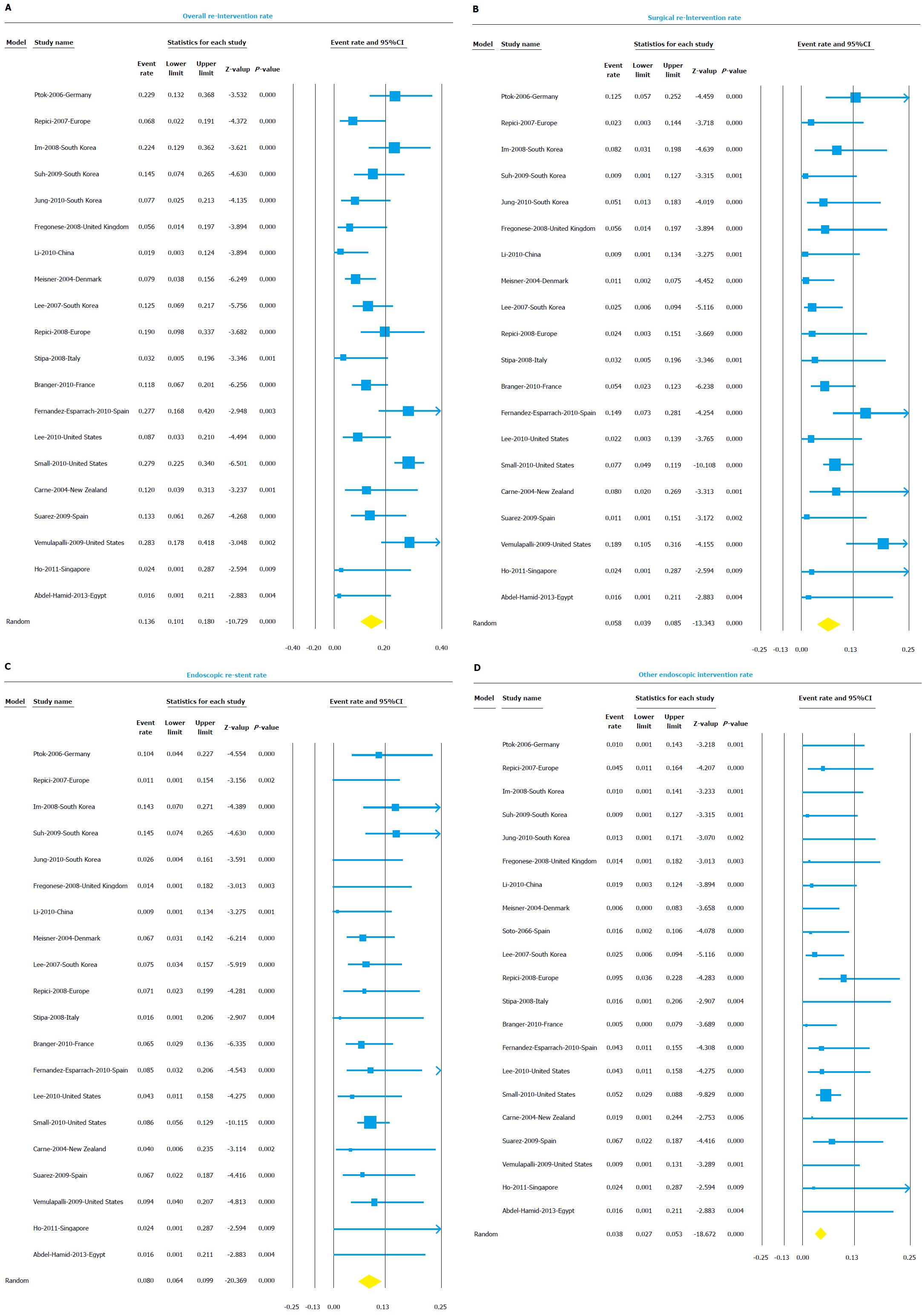

Twenty studies reported unplanned surgical or endoscopic re-interventions after SEMS placement and were included in the analysis. The overall re-intervention rate was 13.6% (95%CI: 10.1-18.0) (Figure 5A). The I2 value for heterogeneity analysis was 69. Once again, re-interventions were required more frequently in palliation group (16.7%, 95%CI: 11.8-22.9) compared to BTS group (3.3%, 95%CI: 1.2-8.4).

Unplanned emergency surgeries were needed in 5.8% (95%CI: 3.9-8.5) of patients (Figure 5B). Rescue surgeries were more frequently needed in palliation group (7.6%, 95%CI: 4.1-13.8) compared to BTS group (3.2%, 1.1-8.7).

Repeat endoscopy with re-stent placement was needed in 8.0% (95%CI: 6.4-9.9) of cases (Figure 5C). Repeat endoscopy with interventions other than stent placement was observed in 3.8% (95%CI: 2.7-5.3) of cases (Figure 5D). These endoscopic intervention included endoscopy to control bleeding or to dis-impact fecal material blocking the stent. The results of the subgroup analysis for all re-interventions based on indication, center, design, and region are shown in detail in Table 4.

| Category and subgroups | Studies | Event rate (%) | 95%CI | P value | I2 value | |

| Overall re-intervention rate | 20 | 13.6 | 10.1-18.0 | 0.000 | 68.79 | |

| Indication | Palliation | 8 | 16.7 | 11.8-22.9 | 0.077 | 45.30 |

| BTS | 4 | 3.3 | 1.2-8.4 | 0.758 | 0.00 | |

| Center | Single Center | 17 | 14.2 | 10.3-19.2 | 0.000 | 70.10 |

| Multicenter | 3 | 10.3 | 4.3-22.6 | 0.114 | 53.94 | |

| Design | Prospective | 7 | 14.8 | 9.5-22.4 | 0.069 | 48.81 |

| Retrospective | 12 | 13.6 | 9.1-19.9 | 0.000 | 75.17 | |

| Region | Asia | 6 | 11.6 | 6.8-19.3 | 0.066 | 51.74 |

| Europe | 9 | 13.2 | 8.8-19.4 | 0.011 | 59.63 | |

| North America | 3 | 14.7 | 11.3-19.0 | 0.034 | 70.54 | |

| Surgical intervention rate | 20 | 5.8 | 3.9-8.5 | 0.011 | 46.79 | |

| Indication | Palliation | 8 | 7.6 | 4.1-13.8 | 0.048 | 50.62 |

| BTS | 4 | 3.2 | 1.1-8.7 | 0.641 | 0.00 | |

| Center | Single Center | 17 | 6.1 | 4.0-9.2 | 0.009 | 50.50 |

| Multicenter | 3 | 3.6 | 1.3-9.2 | 0.675 | 0.00 | |

| Design | Prospective | 7 | 5.1 | 2.6-9.8 | 0.193 | 30.76 |

| Retrospective | 12 | 5.9 | 3.5-9.9 | 0.007 | 57.59 | |

| Region | Asia | 6 | 4.2 | 2.2-7.9 | 0.411 | 0.81 |

| Europe | 9 | 5.4 | 2.9-9.9 | 0.051 | 48.24 | |

| North America | 3 | 9.2 | 3.7-21.2 | 0.016 | 75.87 | |

| Endoscopic re-stent rate | 20 | 8.0 | 6.4-9.9 | 0.439 | 2.15 | |

| Indication | Palliation | 8 | 9.7 | 6.6-14.2 | 0.304 | 16.02 |

| BTS | 4 | 1.5 | 0.4-5.7 | 0.973 | 0.00 | |

| Center | Single Center | 17 | 8.3 | 6.6-10.2 | 0.486 | 0.00 |

| Multicenter | 3 | 3.9 | 1.1-12.3 | 0.296 | 17.95 | |

| Design | Prospective | 7 | 8.4 | 5.3-13.1 | 0.320 | 14.45 |

| Retrospective | 12 | 7.9 | 6.1-10.1 | 0.486 | 0.00 | |

| Region | Asia | 6 | 8.5 | 4.5-15.3 | 0.113 | 43.89 |

| Europe | 9 | 6.8 | 4.8-9.7 | 0.706 | 0.00 | |

| North America | 3 | 8.3 | 5.7-11.8 | 0.600 | 0.00 | |

| Other endoscopic intervention rate | 21 | 3.8 | 2.7-5.3 | 0.620 | 0.00 | |

| Indication | Palliation | 8 | 3.1 | 1.5-6.1 | 0.601 | 0.00 |

| BTS | 4 | 1.8 | 0.5-6.0 | 0.993 | 0.00 | |

| Center | Single Center | 18 | 3.4 | 2.3-4.8 | 0.737 | 0.00 |

| Multicenter | 3 | 6.3 | 2.7-13.7 | 0.333 | 8.99 | |

| Design | Prospective | 7 | 4.2 | 2.3-7.7 | 0.412 | 1.59 |

| Retrospective | 13 | 3.7 | 2.5-5.5 | 0.553 | 0.00 | |

| Region | Asia | 6 | 1.8 | 0.8-4.3 | 0.980 | 0.00 |

| Europe | 10 | 3.7 | 2.0-6.6 | 0.280 | 17.68 | |

| North America | 3 | 4.7 | 2.9-7.8 | 0.475 | 0.00 | |

Heterogeneity was present in the analysis and was further explored by performing multiple subgroup analysis as shown in Tables 2, 3 and 4. For each analysis, sensitivity analysis by omitting one study at a time to evaluate the effect of single study on overall analysis was used to further explore heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis did not reveal any particular study responsible for heterogeneity.

Funnel plots for the publication bias with respect to both technical and clinical success are shown in Figure 6, respectively. Rejection of N test indicated that for the combined two-tailed P value were non-significant (P > 0.05); and with no significant findings, it would take an additional 4517 studies. Using the random effects model the overall technical success rate was 94% (95%CI: 0.92-0.96). After publication bias adjustment using “Trim and Fill”, the computed overall technical success rate was 93% (95%CI: 0.90-0.95).

Our meta-analysis of 30 included studies showed overall clinical and technical success rates of 90.6% and 94%, respectively. Further subgroup analysis showed different technical and clinical success rates respectively for studies that originated from Europe (92.8% and 89.1%), Asia (95.9% and 92.1%), and North America (96% and 92.5%). This could be related to the differences in patient population, extent and severity of colorectal obstruction, procedural volume, and training and experience of endoscopist. However, due to inconsistent reporting and lack of availability of these data, meta-regression analysis was not possible. The common reasons for technical failure were the following: Inability to pass guide wire through region of obstruction, occurrence of iatrogenic perforation during insertion, presence of metachronous bowel obstruction, miscalculation of length of stricture and presence of tortuousities or kinks in colonic lumen making insertions difficult. Based on a retrospective review of 412 patients where SEMSs were used for malignant colorectal obstruction, Yoon et al[48] reported that presence of carcinomatosis, extracolonic origin of tumor,and proximal site of obstruction were the factors related to technical failure. Similarly no additional chemotherapy, dilation prior to stent placement, and extracolonic origin of the tumor were related to long-term clinical failure in the palliation group[48].

The overall adverse event rate in the SEMS group was 23.1%, with stent obstruction, migration, and perforation being the most common adverse events. Tenesmus, intra-abdominal abscesses and rectovesical fistulas were also reported as rare adverse events of SEMS in included studies. The overall rate of adverse event was greater when SEMSs were used for palliation (27.3%) when compared to their use as a BTS (13.8%); especially the frequency of stent obstruction (9.5% vs 1.9%) and stent migration (10.2% vs 4.1%) were higher in the palliation group, while the rate of perforation was comparable between both the groups (5.4% vs 4.0%). This increased adverse event rate in the palliation group was merely a function of the fact that the stent stayed for longer duration in palliation cases, so is more likely to eventually obstruct or migrate. Male sex, complete obstruction, stricture dilation during SEMS insertion, experience of the operator and stent diameter ≤ 22 mm, were identified as risk factors for adverse event related to SEMS placements[5,9]. Small et al[11] reported a threefold increase in the rate of perforation in patients receiving Bevacizumab™ therapy after SEMS placement. Patients who had received Bevacizumab™ therapy prior to SEMS placement showed no increased susceptibility to perforation[11]. Stool impaction, tumor ingrowth or tumor outgrowth were major reasons for stent obstruction[24,39,44].

Re-intervention measures including unplanned surgery 6.0% (95%CI: 4.0-8.9), endoscopic re-stenting 8.2% (95%CI: 6.6-10.1) and other endoscopic interventions 3.9% (95%CI: 2.8-5.4) were performed in 14.3% (95%CI: 10.7-18.9) of the patients. Re-interventions after SEMS placements were needed more often in the palliative group 16.7% (95%CI: 11.8-22.9) than in the BTS group 3.9% (95%CI: 1.3-11.4), which also might have attributed to higher incidence of long-term clinical failure in the palliation group. Adverse events such as SEMS migration and obstruction were chiefly managed endoscopically by procedures including reinsertion of stent, removal and replacement of stent, insertion of additional stents and trimming of the stent by argon plasma coagulation; whereas perforation was usually managed by surgical intervention.

Use of SEMS for decompression offers several advantages. In a palliative setting, it provides a better quality of life by avoiding a surgery with probable colostomy and significantly reduces hospital stay. In an emergency BTS setting, it allows time for bowel preparation, a full workup, and hyperalimentation of the patient prior to definitive surgery and thus increases likelihood of single stage colonic resection and anastomosis, with lower morbidity and mortality. To date, there are four RCTs[5,41,43,46] that evaluated endoscopic SEMS for BTS vs ES. There are no RCTs evaluating palliative SEMS vs palliative surgery. First RCT was a single center trial by Cheung et al[41] that evaluated SEMS for BTS vs ES in 48 patients and reported that patients with SEMS as BTS followed by laparoscopic surgery had significantly less lower pain and cumulative blood loss, incidence of anastomotic leak, and infection in wound infection. Also, patients in SEMS group had significantly more successful one stage operation (16 vs 9, P = 0.04)[41]. The SEMS placements in the study were done by two dedicated endoscopists[41]. In contrast, more recently van Hooft et al[5] evaluated SEMS as BTS against ES in a multicenter (25 hospitals in Netherlands) RCT. Two successive interim analyses showed increased 30 d mortality in colonic stenting group and this study was stopped[12]. At final analysis of 98 patients (SEMS 47, ES 51), no difference was seen between two groups in 30 d mortality, morbidity, and stoma rate. This study had a relatively low technical success rate of only 70% and a high perforation rate of 20%, which are not the experience at most tertiary centers. This may be attributable to several factors. In order to increase recruitment, the study was not confined to tertiary care centers and endoscopists only had to have prior experience in deploying 10 colonic stents to participate in this study. Twenty-five centers performed 47 stent placements, with some presumably low volume centers performing only a single stent placement. The experience of the endoscopists at low volume centers may therefore have been a significant factor in modulating these results. Finally a higher than usual proportion (70%) of patients in this study had complete obstruction compared with most other series and this population can be expected to have a greater morbidity. In patients with complete obstruction, SEMS placement is difficult and it is a known risk factor for adverse events after SEMS placement[11]. Both additional RCTs[43,46] concluded that both SEMS and ES are feasible with trend towards lower post-operative morbidity and mortality with SEMS placement.

In conclusion, our meta-analysis showed that in CRC patients with malignant colonic obstruction, use of SEMS for palliation or as a BTS was quite efficacious with more than 90% of the cases achieving technical and clinical success. The overall adverse event rate was 23.5%, with the major adverse events being obstruction (8.3%), stent migration (7.6%), and perforation (4.9%). Also up to 15% of the patients required endoscopic and surgical re-interventions. Therefore, while choosing between ES and SEMS insertion it is advisable to individualize each decision after discussing the risks and benefits of both with the patients. Further prospective studies comparing the outcomes, in particular the adverse event rates between high and low volume centers for surgery and stent placements are desirable to provide further insights in the management of malignant colonic obstruction.

Malignant colonic obstruction is present in about 7% to 29% of the colorectal patients. Conventional treatment such as elective surgery is present, but has high chances of morbidity and mortality. Introduction of self-expandable metal stent (SEMS) is an initial therapy for malignant colonic obstruction provided an effective alternative, but long term outcomes are still warranted and under study.

The meta-analysis evaluates the efficacy of SEMS over emergency surgery in colorectal patients having malignant colonic obstruction.

The key findings of the study indicate that use of SEMS significantly reduces the mortality and morbidity rates among colorectal cancer (CRC) patients. The authors found 91% of clinical success rate and 23% of complication rate when SEMS was used. Migration and perforation were among the most common complications observed when SEMS was used. Further interventions were required in about 14% of the patients.

SEMS is a safe device and its use can make it a more effective screening tool to prevent malignant colonic obstruction in CRC patients.

A SEMS is a metallic tube used to hold and open a structure in the gastrointestinal tract. It helps in the passage of food, stool and other secretions. These stents are placed in gastrointestinal tract with the help of endoscopy either through mouth or through colon. Fluoroscopy is the other method used to place these stents.

This is a good paper.

P- Reviewer: Cheung HYS, Grund KE, Tsujikawa T S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK

| 1. | Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8406] [Cited by in RCA: 8971] [Article Influence: 690.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Thosani N, Guha S, Singh H. Colonoscopy and colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2013;42:619-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Deans GT, Krukowski ZH, Irwin ST. Malignant obstruction of the left colon. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1270-1276. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Smothers L, Hynan L, Fleming J, Turnage R, Simmang C, Anthony T. Emergency surgery for colon carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:24-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | van Hooft JE, Bemelman WA, Oldenburg B, Marinelli AW, Lutke Holzik MF, Grubben MJ, Sprangers MA, Dijkgraaf MG, Fockens P. Colonic stenting versus emergency surgery for acute left-sided malignant colonic obstruction: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:344-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 303] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Spinelli P, Dal Fante M, Mancini A. Self-expanding mesh stent for endoscopic palliation of rectal obstructing tumors: a preliminary report. Surg Endosc. 1992;6:72-74. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Law WL, Choi HK, Chu KW. Comparison of stenting with emergency surgery as palliative treatment for obstructing primary left-sided colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1429-1433. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Carne PW, Frye JN, Robertson GM, Frizelle FA. Stents or open operation for palliation of colorectal cancer: a retrospective, cohort study of perioperative outcome and long-term survival. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1455-1461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sebastian S, Johnston S, Geoghegan T, Torreggiani W, Buckley M. Pooled analysis of the efficacy and safety of self-expanding metal stenting in malignant colorectal obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2051-2057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fernández-Esparrach G, Bordas JM, Giráldez MD, Ginès A, Pellisé M, Sendino O, Martínez-Pallí G, Castells A, Llach J. Severe complications limit long-term clinical success of self-expanding metal stents in patients with obstructive colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1087-1093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Small AJ, Coelho-Prabhu N, Baron TH. Endoscopic placement of self-expandable metal stents for malignant colonic obstruction: long-term outcomes and complication factors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:560-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | van Hooft JE, Fockens P, Marinelli AW, Timmer R, van Berkel AM, Bossuyt PM, Bemelman WA. Early closure of a multicenter randomized clinical trial of endoscopic stenting versus surgery for stage IV left-sided colorectal cancer. Endoscopy. 2008;40:184-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.2. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2009 [Updated September 2009]. Available from: www.cochrane-handbook.org. |

| 15. | DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177-188. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539-1558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21630] [Cited by in RCA: 25813] [Article Influence: 1122.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629-634. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455-463. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Sterne JA, Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:1046-1055. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Sterne JA, Egger M, Smith GD. Systematic reviews in health care: Investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in meta-analysis. BMJ. 2001;323:101-105. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Repici A, Fregonese D, Costamagna G, Dumas R, Kähler G, Meisner S, Giovannini M, Freeman J, Petruziello L, Hervoso C. Ultraflex precision colonic stent placement for palliation of malignant colonic obstruction: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:920-927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ptok H, Meyer F, Marusch F, Steinert R, Gastinger I, Lippert H, Meyer L. Palliative stent implantation in the treatment of malignant colorectal obstruction. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:909-914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Fregonese D, Naspetti R, Ferrer S, Gallego J, Costamagna G, Dumas R, Campaioli M, Morante AL, Mambrini P, Meisner S. Ultraflex precision colonic stent placement as a bridge to surgery in patients with malignant colon obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:68-73. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Meisner S, Hensler M, Knop FK, West F, Wille-Jørgensen P. Self-expanding metal stents for colonic obstruction: experiences from 104 procedures in a single center. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:444-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Soto S, López-Rosés L, González-Ramírez A, Lancho A, Santos A, Olivencia P. Endoscopic treatment of acute colorectal obstruction with self-expandable metallic stents: experience in a community hospital. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1072-1076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Repici A, De Caro G, Luigiano C, Fabbri C, Pagano N, Preatoni P, Danese S, Fuccio L, Consolo P, Malesci A. WallFlex colonic stent placement for management of malignant colonic obstruction: a prospective study at two centers. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:77-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Stipa F, Pigazzi A, Bascone B, Cimitan A, Villotti G, Burza A, Vitale A. Management of obstructive colorectal cancer with endoscopic stenting followed by single-stage surgery: open or laparoscopic resection? Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1477-1481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Branger F, Thibaudeau E, Mucci-Hennekinne S, Métivier-Cesbron E, Vychnevskaia K, Hamy A, Arnaud JP. Management of acute malignant large-bowel obstruction with self-expanding metal stent. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25:1481-1485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | West M, Kiff R. Stenting of the colon in patients with malignant large bowel obstruction: a local experience. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2011;42:155-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Meisner S, González-Huix F, Vandervoort JG, Goldberg P, Casellas JA, Roncero O, Grund KE, Alvarez A, García-Cano J, Vázquez-Astray E. Self-expandable metal stents for relieving malignant colorectal obstruction: short-term safety and efficacy within 30 days of stent procedure in 447 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:876-884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Súarez J, Jiménez J, Vera R, Tarifa A, Balén E, Arrazubi V, Vila J, Lera JM. Stent or surgery for incurable obstructive colorectal cancer: an individualized decision. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25:91-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Im JP, Kim SG, Kang HW, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. Clinical outcomes and patency of self-expanding metal stents in patients with malignant colorectal obstruction: a prospective single center study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:789-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Suh JP, Kim SW, Cho YK, Park JM, Lee IS, Choi MG, Chung IS, Kim HJ, Kang WK, Oh ST. Effectiveness of stent placement for palliative treatment in malignant colorectal obstruction and predictive factors for stent occlusion. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:400-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Jung MK, Park SY, Jeon SW, Cho CM, Tak WY, Kweon YO, Kim SK, Choi YH, Kim GC, Ryeom HK. Factors associated with the long-term outcome of a self-expandable colon stent used for palliation of malignant colorectal obstruction. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:525-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Li YD, Cheng YS, Li MH, Fan YB, Chen NW, Wang Y, Zhao JG. Management of acute malignant colorectal obstruction with a novel self-expanding metallic stent as a bridge to surgery. Eur J Radiol. 2010;73:566-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Lee KM, Shin SJ, Hwang JC, Cheong JY, Yoo BM, Lee KJ, Hahm KB, Kim JH, Cho SW. Comparison of uncovered stent with covered stent for treatment of malignant colorectal obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:931-936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Park S, Cheon JH, Park JJ, Moon CM, Hong SP, Lee SK, Kim TI, Kim WH. Comparison of efficacies between stents for malignant colorectal obstruction: a randomized, prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:304-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Lee HJ, Hong SP, Cheon JH, Kim TI, Min BS, Kim NK, Kim WH. Long-term outcome of palliative therapy for malignant colorectal obstruction in patients with unresectable metastatic colorectal cancers: endoscopic stenting versus surgery. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:535-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Ng KC, Law WL, Lee YM, Choi HK, Seto CL, Ho JW. Self-expanding metallic stent as a bridge to surgery versus emergency resection for obstructing left-sided colorectal cancer: a case-matched study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:798-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Cheung HY, Chung CC, Tsang WW, Wong JC, Yau KK, Li MK. Endolaparoscopic approach vs conventional open surgery in the treatment of obstructing left-sided colon cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2009;144:1127-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Guo MG, Feng Y, Zheng Q, Di JZ, Wang Y, Fan YB, Huang XY. Comparison of self-expanding metal stents and urgent surgery for left-sided malignant colonic obstruction in elderly patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2706-2710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Ho KS, Quah HM, Lim JF, Tang CL, Eu KW. Endoscopic stenting and elective surgery versus emergency surgery for left-sided malignant colonic obstruction: a prospective randomized trial. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:355-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Lee JH, Ross WA, Davila R, Chang G, Lin E, Dekovich A, Davila M. Self-expandable metal stents (SEMS) can serve as a bridge to surgery or as a definitive therapy in patients with an advanced stage of cancer: clinical experience of a tertiary cancer center. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3530-3536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Vemulapalli R, Lara LF, Sreenarasimhaiah J, Harford WV, Siddiqui AA. A comparison of palliative stenting or emergent surgery for obstructing incurable colon cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1732-1737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Ghazal AH, El-Shazly WG, Bessa SS, El-Riwini MT, Hussein AM. Colonic endolumenal stenting devices and elective surgery versus emergency subtotal/total colectomy in the management of malignant obstructed left colon carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1123-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Pirlet IA, Slim K, Kwiatkowski F, Michot F, Millat BL. Emergency preoperative stenting versus surgery for acute left-sided malignant colonic obstruction: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1814-1821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Yoon JY, Jung YS, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH, Cheon JH. Clinical outcomes and risk factors for technical and clinical failures of self-expandable metal stent insertion for malignant colorectal obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:858-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |