Published online Aug 26, 2014. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v2.i3.64

Revised: May 27, 2014

Accepted: June 27, 2014

Published online: August 26, 2014

Processing time: 172 Days and 4.4 Hours

AIM: To validate the Arabic version of abeer children dental anxiety scale.

METHODS: Two ethical approvals for this study were obtained from United Arab Emirates, Ministry of Health and Dubai Health Authority; reference number: 2011/57. The Abeer children dental anxiety scale (ACDAS) was translated from English to Arabic by the native speaker chief investigator, and then back translated by another native speaker in Dubai (AS) to ensure comparability with the original one. Part C of ACDAS was excluded for the schoolchildren because those questions were only applicable for children at the dentist with their parents or legal guardian. A total of 355 children (6 years and over) were involved in this study; 184 in Dubai, 96 from the Religious International Institute for boys and 88 from Al Khansaa Middle School for girls. A sample of 171 children was assessed for external validity (generalizability) from two schools in different areas of London in the United Kingdom.

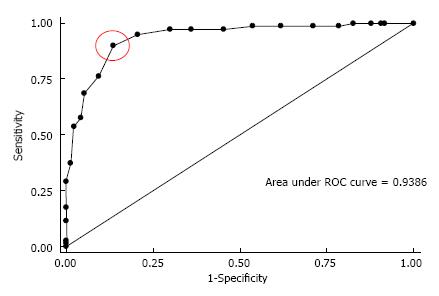

RESULTS: Receiver operating characteristic curve showed that the cut-off ≥ 26 for ACDAS gave the optimal results for sensitivity = 90% (95%CI: 81.2%- 95.6%), and specificity = 86.6% (95%CI: 78.2%- 92.7%), with AUROC = 0.93 (95%CI: 0.90-0.97). Cronbach’s Alpha (α) was 0.90 which indicated good internal consistency. Results of the external validity assessing the agreement between ACDAS and dental subscale of the children's fear survey schedule was substantial for the East London school (κ = 0.68, 95%CI: 0.53-0.843); sensitivity = 92.9% (95%CI: 82.7%-98.0%); specificity = 73.5% (95%CI: 55.6%-87.1%) and almost perfect for the Central London school (κ = 0.79; 95%CI: 0.70-0.88); sensitivity = 96.4% (95%CI: 81.7%-99.9%); specificity = 65.9%, (95%CI: 57.4%-73.8%).

CONCLUSION: The Arabic ACDAS is a valid cognitive scale to measure dental anxiety for children age 6 years or over.

Core tip: The Abeer children dental anxiety scale (ACDAS) scale is different from existing scales as it is the first dental anxiety scale for children which correlate dental anxiety with cognitive status. It can recognise the stimuli for dental anxiety in a logical order, and has questions concerning the expectation of the child’s legal guardian about the behaviour of the child before the treatment, whether the child has any previous dental treatment experience and the dentist’s rating for the child’s behaviour at the end of the treatment at the same visit. Finally, when assessing the external validity of the binary ACDAS, it was shown that its results compared favourably with those of the main study (κ = 0.79, sensitivity = 96.4%, specificity = 65.9%) when applied to children in a different London school (κ = 0.68, sensitivity = 92.9%, specificity = 73.5%). Therefore, ACDAS was shown to work well in two different locations with different children, which suggests that it is a generalisable scale. Based on the findings of this study, it is proposed that the ACDAS encompasses the required criteria for the gold standard dental anxiety scale for children.

- Citation: Al-Namankany A, Ashley P, Petrie A. Development of the first Arabic cognitive dental anxiety scale for children and young adults. World J Meta-Anal 2014; 2(3): 64-70

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v2/i3/64.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v2.i3.64

Children dental anxiety has been a matter of concern for many years but despite this the etiology is still not entirely understood[1]. Anxiety may occur without cause, or it may be based on a real situation that leads to a reaction that is out of proportion to what would normally be expected. Severe anxiety can have a serious impact on daily life and effect quality of life and its different dimensions, such as speaking, eating, and appearance, and through these also social intercourse[2]. Dental anxiety is cumulative over time, and its development is influenced by multiple variables. It is most likely to start in childhood[3]. There are three general sources of information that have been evaluated as measures of anxiety for children and adults: (1) the behavioral measures, which is what the patient does, such as overt distress, general behavior, or specific motor acts like gripping the chair arms tightly. The results of these measures tend to be more subjective than the objective ones; if two dentists are observing the behavior of the same patient on the same time there is no guarantee that both will score the patient in a similar way. The differences in scoring could depend on the time of the appointment, the experience, the temperament, the age, and the gender of the dentist. Hence, the reliability of these measures will not be strong enough if they are used for research purposes. However, it might be the only method that could be used with preschool children; (2) the physiological measures, which is the measurement of the patient’s responses to the dental anxiety, such as rapid breathing, profuse sweating, muscle tension, pulse rate, or heart rate. These measures were neither reliable nor practical in use with children because the scene, the sound, and the application of the equipment might increase the child’s anxiety level[4]. The use of the physiological measures were found to be less appropriate for assessing dental fear in children[5] for several reasons: the standard normal reading for children will vary and depend on age of the child; the results of these measures could be overlapped with current medical problems; the requirement of knowledge and training on how to use these equipments; wrong results by faulty machines; it is not available in all dental clinics; the practicality of using it in terms of cost, time, maintenance and a space in the clinic; last but not least. It is not appropriate to be used for children of all age groups; and (3) the self reported measures, which is what the patient says about his/her fear via direct report or scaling, interview, or inventory[6,7]. These measures are the most reliable measures for children who are able to read and have the cognitive ability to understand how to report their anxiety on the scale. Previous studies found that, in adult patients, the self reported anxiety scale can distinguish between high or low dental anxiety in terms of avoidance or distress behaviors. This may not be the case in preschool children; the ability of the young children may not be fully developed and they tend to report more fears regardless of the situation and more likely to show anxiety at separation from the parent. For those young children, the use of the behavioral measures is the best option[8].

Studies of dental anxiety in children rather than in adults may allow us to more reliably investigate the causes and management of dental anxiety. This is due to the limited reliability and validity of adult dental anxiety studies and to the extensive time span between the onset of the anxiety during the childhood and these studies[9]. Although measurement of dental anxiety is important for research and delivery of high quality clinical care, it is the corner stone of dental anxiety management.

The development of self-reported measures was started in early 1960s and has continued up until the present. Dental anxiety measures have been developed in order to help the dentist detect anxious patients in order to provide better management and treatment. The degree of belief in negative cognition is associated with the severity of DA[10], the negative thinking patterns of the anxious individual is centered on danger and harm. The cognitive measures are widely used as self-report scales that request the patient to respond to list of statements or questions, these measures could be incorporated into pediatric DAM[11]. Abeer children dental anxiety scale (ACDAS) is the first children dental anxiety scale that incorporated the cognitive questions and is a valid cognitive scale to measure DA for children aged ≥ 6 years[12]. Although there are 14 different dental anxiety scales for children, some of them have been validated in many languages[13]; to date there is no DA scale that validated in Arabic language. Hence, the objective of this study was to validate the Arabic version of ACDAS in order to extend its benefits to more people and to be the first Arabic dental anxiety scale.

This study was made up of two parts, development of a new scale and then validation of this scale. According to the regulations of the United Arab of Emirates, two ethical approvals for this study were obtained from the Ministry of Health and Dubai Health Authority; Reference number: 2011/57.

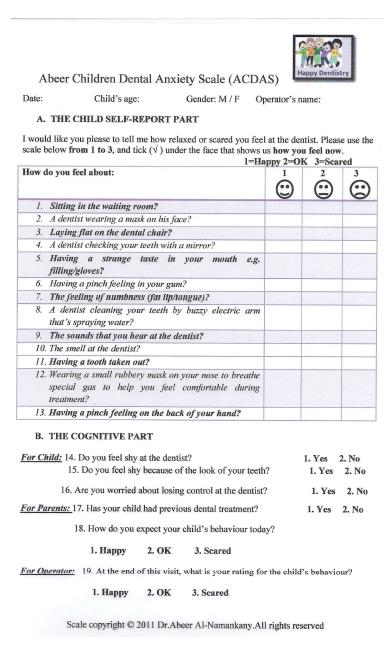

The previously validated (Abeer Children Dental Anxiety Scale “ACDAS”)[12] was translated from English to Arabic by the native speaker chief investigator, and then back translated by another native speaker in Dubai to ensure comparability with the original one (Figure 1). ACDAS is a 19 item, cognitive scale which can be used for children from age 6 years and over, we proposed the following name - Abeer Children Dental Anxiety Scale-Arabic (ACDAS-Arabic). It is made up of three parts (Figure 1): (1) this comprises 13 self-reported questions arranged in logical order. Each question uses three faces as a response set. Face “1” represents the feeling of a relaxed not scared “Happy”; face “2” represents a neutral/fair feeling “OK”; and face “3” represents the anxious feeling “Scared”. The child is asked to tick under the face that best represents the child’s response to the question and a mark (1, 2 or 3) is assigned accordingly. The range of values is therefore from 13 to 39; (2) this comprises three self-reported questions which afford a cognitive assessment, each question uses “Yes” or “No” as a response; and (3) this comprises three questions for further assessment of the child as reported by the legal guardian and the dentist, each question uses“Yes” or “No” as a response.

The inclusion criteria for this study were children aged of 6 years or over, with no learning disability, and the ability to read Arabic. The children had to be at least 6 years of age, because younger children do not have the cognitive complexity required to report and react to dental situations accurately and they may not have the experience of dental situations[14]. A convenience sample of 184 students participated in this study; 96 males (The Religious International Institute), and 88 females (Al Khansaa Middle School). The study composed of two parts: assessment of reliability and validity, and assessment of generalizability or external validity.

On the first visit, the local department of school health in Dubai gave permission for the study to be conducted on children in specific schools in their jurisdiction. In addition, permission from each school principal and a verbal consent by the students were also obtained prior to the start of the study. During the class time and in the presence of the teacher for each class, ACDAS-Arabic was completed by each child after being administered twice, once by each of two observers in order to measure the inter-observer reliability, and, in addition, the chief investigator administered ACDAS-Arabic twice, one week apart, to each child in order to measure the intra-observer reliability. Each child on the first visit also completed dental subscale of the children’s fear survey schedule (CFSS-DS) after it was administered by the chief investigator in order to assess the validity of ACDAS-Arabic. On the second visit, seven students (4 males/3 females) who participated in the first visit were absent. Therefore there were seven missing from the total sample (n = 184) which resulted in the 177 participants for the analysis.

Statistical methods for numerical anxiety scores: Initially the scores from Part-A of ACDAS-Arabic (the first 13 questions) were summed to provide a numerical anxiety score for each child at each visit. Intra-observer and inter-observer agreement were each assessed by performing a paired t-test to determine if there was a systematic effect, creating a Bland Altman diagram to assess whether the agreement was independent of the magnitude of the score, calculating the British Standards repeatability/reliability coefficient to provide the maximum likely difference between a pair of measurements, and determining Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient as a measure of agreement. The Pearson correlation coefficient was determined between the scores of ACDAS-Arabic and CFSS-DS to investigate concurrent validity, and Cronbach’s alpha evaluated to assess internal consistency.

Statistical methods for the two anxiety categories (anxious/ not anxious): Creating a categorical outcome facilitates the use of the ACDAS-Arabic scale for clinical and research purposes in terms of translating its numerical score into clinically relevant outcomes (anxious/not anxious). The ACDAS-Arabic questionnaire results from the second visit of the 177 children were used to determine the sensitivity and the specificity for different cut-off values of the total score for Part A to distinguish anxious from not anxious children. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, plotting the sensitivity against 100, specificity for different cut-offs, was used to select an optimal cut-off value for the new scale. The classification of anxious and not anxious for these 177 children was also determined using the previously published optimal cut-off of ≥ 36 for the CFSS-DS scale[9].

Cohen’s kappa (k) with its confidence interval (CI) was evaluated to assess intra-observer and inter-observer reliability, and the discriminative validity when comparing the binary outcomes of ACDAS-Arabic and CFSS-DS. Convergent validity was assessed by using the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test when expected frequencies were small to compare dental anxiety with each of the other variables defined by the questions in Part B of ACDAS-Arabic.

In order to know whether the scale and its dichotomized score will work well in populations that are different from the one from which it was derived, and to assess whether the cut-off “26” of ACDAS produces the similar results in terms of anxiety for different samples of children, a sample of 171 children was assessed for external validity (generalizability) from two schools in different areas of London in the United Kingdom; 81 from St. Alban’s Primary school in Central London and 90 from Cayley primary school in East London. In addition, bootstrapping[15] was used because data had not been collected at other schools on the visit to Dubai and it was not possible to travel to Dubai to collect additional data. Bootstrapping is a simulation process which involves estimating the parameter of interest from each of many random samples of size 177 (in this instance) by sampling with replacement from the original sample of size 177.

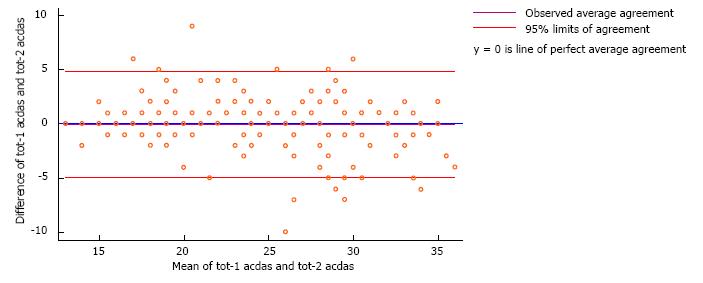

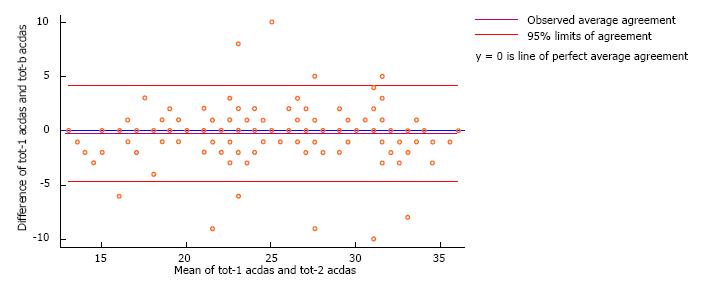

The analysis of the numerical anxiety scores from ACDAS-Arabic indicated good reliability for both intra- and inter-observer agreement (Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient 0.91 (95%CI: 0.89-0.94) and 0.92 (95%CI: 0.90-0.94), respectively; a value of 1 indicates perfect agreement. There was no evidence of a funnel effect in either of the Bland Altman diagrams assessing intra- and inter-observer reliability, and the limits of agreement for them were -4.93 to 4.84 and -3.87 to 5.47, respectively (Figures 2 and 3). The British Standards repeatability/reliability coefficient indicates the maximum likely differences between a pair of measurements were 4.9 and 4.5 for intra-and inter observer reliability, respectively. Using the first set of results for ACDAS-Arabic from the principal observer, the Pearson correlation coefficient between the ACDAS-Arabic and CFSS-DS indicated moderate concurrent validity (r = 0.46, P = 0.007). Cronbach’s Alpha (α) for ACDAS-Arabic was 0.90 which indicated a good internal consistency.

The sensitivity and the specificity of the ACDAS-Arabic were determined for different cut-off points of the numerical anxiety scores (i.e., the sum of the scores from Questions 1 to 13) as a means of distinguishing anxious from not anxious children. The cut-off point closest to the top left hand corner of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC curve) is circled in red (Figure 4). It gives the optimal results for sensitivity (90.0%, 95%CI: 81.2%-95.6%) and specificity (86.6%, 95%CI: 78.2%-92.7%). The area under the curve was 0.93 (95%CI: 0.90-0.97) as indicated in Figure 3. (A test which is perfect at discriminating between the two outcomes has an area under the curve of one).

There was almost perfect intra-observer agreement for the binary anxiety outcomes, using a cut-off of ≥ 26 for ACDAS-Arabic to indicate anxiety, when the questionnaire was administered one week apart by the chief investigator (κ = 0.91; 95%CI: 0.85-0.97), and almost perfect inter-observer agreement (κ = 0.89; 95%CI: 0.82-0.96). There was substantial agreement between the two binary anxiety scales (ACDAS-Arabic with a cut-off of ≥ 26 and CFSS-DS with a cut-off of ≥ 36) (κ = 0.76; 95%CI: 0.67-0.86), providing evidence of good discriminative validity.

Convergent validity indicated that there was a strong relationship between DA and cognition. The correlation coefficient is statistically significant (P = 0.004) for question 14: “Do you feel shy at the dentist?”. There was no evidence of a linear relationship between the score of dental anxiety that was reported by the child and his/her answer to the question 15: “Do you feel shy because of the way your teeth look?” (P = 0.25). However, there was a highly significant relationship between child’s DA and the cognitive question16: “Are you worried about losing control at the dentist?” (P < 0.001).

One thousand bootstrap replications for 177 observations showed substantial agreement between the two binary scales (ACDAS-Arabic/CFSS-DS). This result compared favorably with the previous result that was obtained from the two schools in London, as shown in Table 1, which suggested that ACDAS-Arabic is working well in another location for another sample and it is a generalizable scale.

| Central London | Dubai | East London | |

| Kappa (95%CI) | K = 0.79 (0.70-0.88) | K = 0.76 (0.67 -0.86) | K = 0.68 (0.53-0.84) |

| Sensitivity (95%CI) | 96.40% (81.7%-99.9%) | 90% (81.2%-95.6%) | 92.90% (82.7%-98.0%) |

| Specificity (95%CI) | 65.90% (57.4%-73.8%) | 86.60% (78.2%-92.7%) | 73.50% (55.6%-87.1%) |

Given the fact that there is currently no Arabic dental anxiety measure, the idea of the initiator of ACDAS, who is a native Arabic speaker, was to translate ACDAS to Arabic (ACDAS-Arabic) and validate it as the first cognitive and dental anxiety scale in the Arab world. ACDAS was validated as the first cognitive dental anxiety scale for children and adolescents; it included questions about the dental experience in a logical order and not only the most common feared items as the previous scales. Moreover, it included the perception of losing control; embarrassment; self-confidence and the cognitive nature of the child as important factors in anxiety provoking.

This study has shown almost perfect results for both numerical and categorical outcomes; the children had to be at least 6 years of age, because younger children do not have the cognitive complexity required to report and react to dental situations accurately and they may not have the experience of dental situations.

Given the significance of the crucial role of negative cognitive patterns in anxiety evocation that could make the person apprehensive and difficult to treat dentally and who also might not easily comply with anxiety treatment techniques, the present results were in line with the previous similar studies on adults. These demonstrated a strong relation between the negative thoughts and the level of dental anxiety[11,16,17]. The perception of losing control, embarrassment and self-confidence are important factors in anxiety provoking; these results suggest that 91% to 95% of the children who reported negative cognitions on questions 14, 15, and 16 were anxious; 98% were reported in other studies for adults[17]. The cut-off point for anxiety for ACDAS-Arabic (≥ 26) gave the optimal results for sensitivity (86.8%) and specificity (86.2%). These values suggested that ACDAS-Arabic has the ability to identify the anxious and non-anxious individual correctly. In addition, the area under the curve was 0.93: if the score discriminates perfectly, the AUROC equals 1[15].

The strong correlation between the ACDAS-Arabic and the CFSS-DS scores supports the validity of the ACDAS-Arabic in the dental setting, i.e., the ACDAS-Arabic measures what it intends to measure, it includes items that are relevant to the most of children’s dental experience and it asks about the child’s five sensations (i.e., sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch). Moreover, it includes items that are relevant to treatment under inhalation and intravenous sedation. Treatment under general anesthesia was not included because the child will be asleep and will not really face the actual dental experience. ACDAS-Arabic is easy to administer and it took a very short time (3 min) to do so.

One of the limitations of this study was the use of CFSS-DS in its English version for validating the ACDAS-Arabic. To date, there is no Arabic DA scale that could be used instead. Therefore the English version of the CFSS-DS had to be translated into Arabic, and read and explained verbally by the chief investigator.

Another limitation was that the order of administration of the ACDAS-Arabic and the CFSS-DS for the school children was not randomized; it was impossible to do this because of the time restriction, as the administration was during the class time. Because of this time constraint, each child could not have a one-to-one interview with the observer in order to complete the ACDAS-Arabic and the CFSS-DS questionnaires. Instead the questionnaires were read to the class as a whole and the all the children in a class completed them at the same time. A third limitation was that the validation of this scale was planned for both a clinical and school setting but, because of the restrictions of cost and the time that the principal investigator would have had to spend in Dubai to obtain the information from a clinical setting, only school children were used.

It is crucial to understand the importance of measuring children dental anxiety and its correlation with the cognitive status of the child. ACDAS helps to highlight the unmet needs of many children who do not go to dentists because of fear of general anesthesia (GA). While some cases may still require GA, with appropriate anxiety management there is a significant number in whom it could be avoided.

Finally, although prevention is better than the treatment, to date there is no study that includes dental anxiety measurement in the list of preventative strategies which usually includes oral hygiene instruction, diet advice, fissure sealant, chlorhexidine and fluoride application[18]. Therefore, the first author suggests the inclusion of dental anxiety measure as a prevention item from the first visit and throughout the dental treatment. Assessing patients’ thoughts could be a first step on the development of cognitive treatment strategies for dental anxiety.

The Arabic version of ACDAS is a valid and generalizable cognitive dental anxiety scale for children and adolescents.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Abdul Rahim Almarri, Dr Aisha Sultan, Ms. Fayza Albadri, and the head teachers at all schools in Dubai-UAE. Special thanks to Dr. Paul Ashley who encouraged me to conduct this study in Dubai, and to the children who participated in this study.

Dental anxiety is still remain as one of the main problems that caused avoiding visiting the dentists. Assessment of dental anxiety is the first step toward a better management.

The Abeer children dental anxiety scale (ACDAS) scale is different from existing scales as it is the first dental anxiety scale for children which correlate dental anxiety with cognitive status.

It can recognise the stimuli for dental anxiety in a logical order, and has questions concerning the expectation of the child’s legal guardian about the behaviour of the child before the treatment, whether the child has any previous dental treatment experience and the dentist’s rating for the child’s behaviour at the end of the treatment at the same visit.

Finally, when assessing the external validity of the binary ACDAS, it was shown that its results compared favourably with those of the main study (κ = 0.79, sensitivity = 96.4%, specificity = 65.9%) when applied to children in a different London school (κ = 0.68, sensitivity = 92.9%, specificity = 73.5%).

Therefore, ACDAS was shown to work well in two different locations with different children, which suggests that it is a generalisable scale. Based on the findings of this study, it is proposed that the ACDAS encompasses the required criteria for the gold standard dental anxiety scale for children.

The work is well done and structured.

P- Reviewer: Lopez-Jornet P, Tomofuji T S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Townend E, Dimigen G, Fung D. A clinical study of child dental anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38:31-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Luoto A, Lahti S, Nevanperä T, Tolvanen M, Locker D. Oral-health-related quality of life among children with and without dental fear. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2009;19:115-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tickle M, Jones C, Buchannan K, Milsom KM, Blinkhorn AS, Humphris GM. A prospective study of dental anxiety in a cohort of children followed from 5 to 9 years of age. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2009;19:225-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Klingberg G, Berggren U. Dental problem behaviors in children of parents with severe dental fear. Swed Dent J. 1992;16:27-32. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Aartman I, Everdingen T, Hoogstraten J, Schuurs A. Appraisal of Behavioral Measurement Techniques for Assessing Dental Anxiety and Fear in Children: A Review. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 1996;18:153-171. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Atkins CO, Farrington FH. Informed consent and behavior management. Va Dent J. 1994;71:16-20. [PubMed] |

| 7. | McGrath PA. Measurement issues in research on dental fears and anxiety. Anesth Prog. 1986;33:43-46. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Melamed BG. Assessment and management strategies for the difficult pediatric dental patient. Anesth Prog. 1986;33:197-200. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Boman UW, Lundgren J, Elfström ML, Berggren U. Common use of a Fear Survey Schedule for assessment of dental fear among children and adults. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2008;18:70-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | de Jongh A, Muris P, ter Horst G, Duyx MP. Acquisition and maintenance of dental anxiety: the role of conditioning experiences and cognitive factors. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33:205-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ayer W. Psychology and dentistry: mental health aspects of patient care. 1st ed. New York: Haworth Press Inc 2005; . |

| 12. | Al-Namankany A, Ashley P, Petrie A. The development of a dental anxiety scale with a cognitive component for children and adolescents. Pediatr Dent. 2012;34:e219-e224. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Al-Namankany A, de Souza M, Ashley P. Evidence-based dentistry: analysis of dental anxiety scales for children. Br Dent J. 2012;212:219-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Alwin NP, Murray JJ, Britton PG. An assessment of dental anxiety in children. Br Dent J. 1991;171:201-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Petrie A, Sabin C. Medical Statistics at a Glance. 3rd ed. USA: Blackwell Publishing 2009; . |

| 16. | Briers S. Brilliant Cognitive Behavioural Therapy. 1st ed. USA: Prentice Hall 2009; . |

| 17. | De Jongh A. Dental Anxiety: A Cognitive Perspective. : Thesis 1995; . |

| 18. | Sarmadi R, Gahnberg L, Gabre P. Clinicians’ preventive strategies for children and adolescents identified as at high risk of developing caries. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2011;21:167-174. [PubMed] |