Published online Jun 18, 2023. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v11.i5.151

Peer-review started: January 9, 2023

First decision: February 20, 2023

Revised: April 8, 2023

Accepted: June 9, 2023

Article in press: June 9, 2023

Published online: June 18, 2023

Processing time: 158 Days and 2.2 Hours

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a common virus that can cause the first infection in childhood or adolescence and reactivate later in life due to immunosuppression. CMV pneumonia is a rare illness in immunocompetent patients but is one of the most significant opportunistic infections in immunocompromised patients.

To report a case and review published cases of pulmonary CMV infection in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients.

We conducted a systematic search on the MEDLINE (PubMed) database, without date or language restrictions, to identify relevant studies using Medical Subject Headings and Health Science Descriptors. We manually searched the reference lists of the included studies. Simple descriptive analysis was used to summarize the results.

Our search identified 445 references, and after screening, 43 studies reporting 45 cases were included in the final analysis, with 29 (64%) patients being immunocompromised and 16 (36%) being immunocompetent. Fever (82%) and dyspnea (75%) were the most common clinical findings. Thoracic computed tomography showed bilateral ground-glass opacities, a relevant differential diagnosis for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. The majority of patients (85%) received antiviral therapy, and 89% of patients recovered, while 9% of patients died.

CMV pneumonia should be considered as a differential diagnosis for coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia, especially in immunocompromised patients. Clinicians should be aware of the clinical presentation, management, and outcomes of CMV pneumonia to guide appropriate treatment decisions.

Core Tip: The paper reports a case of disseminated cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in an immunocompetent patient who presented with cough, dyspnea, high-grade fever, and jaundice. The patient was diagnosed with CMV pneumonia after developing sepsis and being admitted to the intensive care unit. The study conducted a systematic search on the MEDLINE database to identify published cases of pulmonary CMV infection in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients. The search identified 43 studies reporting 45 cases, with 29 (64%) patients being immunocompromised and 16 (36%) being immunocompetent. Fever and dyspnea were the most common clinical findings, and thoracic computed tomography showed bilateral ground-glass opacities. The majority of patients received antiviral therapy, and 89% of patients recovered, while 9% of patients died. The study highlights that CMV pneumonia should be considered as a differential diagnosis for coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia, especially in immunocompromised patients, and clinicians should be aware of the clinical presentation, management, and outcomes of CMV pneumonia to guide appropriate treatment decisions.

- Citation: Kanika A, Soldera J. Pulmonary cytomegalovirus infection: A case report and systematic review. World J Meta-Anal 2023; 11(5): 151-166

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v11/i5/151.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v11.i5.151

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a DNA virus that belongs to the herpesviridae family and shares similarities with other herpes viruses. In immunocompetent adults, CMV infection is usually asymptomatic and causes mild mononucleosis-like syndrome, typically in childhood or adolescence. However, CMV can cause severe disease and pneumonia in immunocompetent individuals, albeit rarely[1,2]. CMV infection may lead to severe viral pneumonitis in immunocompromised patients, such as those with autoimmune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), allogeneic bone marrow transplantation recipients, or those on immuno

As the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic continues and becomes an endemic, it is crucial to recognize that not all clinical and radiological presentations are solely attributable to COVID-19[10]. Therefore, diagnostic differentiation is essential, and ground-glass opacities (GGOs) must be evaluated in conjunction with other imaging findings, laboratory tests, and clinical features to reach a definitive diagnosis. CMV pneumonia can be diagnosed by detecting the virus in serum and/or respiratory samples such as bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) or tracheal aspiration[10]. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) can be utilized to measure viral loads in blood and BAL fluid[11]. Lung biopsy histopathology is considered the gold standard for diagnosing pulmonary CMV infections, with the presence of CMV inclusion bodies (owl’s eye) in biopsy specimens being confirmatory of lung infection[12]. However, the diagnostic yield of lung biopsy for diagnosing lung CMV infections can vary as inclusions may not always be visualized. Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for CMV in cytological specimens of bronchial washing fluid can also detect CMV[13,14].

The first-line treatment for CMV disease is intravenous ganciclovir and its prodrug, oral valgan

This study aimed to report a case of disseminated CMV in an immunocompetent patient, and systematically review published cases of pulmonary CMV infection in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients.

Chief complaints: A 32-year-old man presented with a cough, dyspnea, high-grade fever, and jaundice.

History of present illness: The patient had no significant medical history and was not taking any medication. Physical examination revealed a temperature of 39.5°C, tachypnea, icteric sclera, and hepatosplenomegaly. He had no skin rash or lymphadenopathy. The initial blood tests showed pancytopenia, elevated liver enzymes, elevated bilirubin, and hypoalbuminemia. CT of the thorax showed GGOs, while CT of the face showed sinusitis, raising suspicion of an infectious etiology.

History of past illness: The patient had no significant past medical history.

Personal and family history: No significant personal or family history was reported.

Physical examination: The patient presented with a temperature of 39.5°C, tachypnea, icteric sclera, and hepatosplenomegaly. He had no skin rash or lymphadenopathy.

Laboratory examinations: Complete blood count revealed a platelet count of 87000/mm³, hemoglobin level of 8.2 g/dL, and leukocyte count of 4830/mm³. Liver function tests showed alkaline phosphatase of 1174 U/L, gamma-glutamyl transferase of 804 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase of 403 U/L, total bilirubin of 17.2 mg/dL, albumin of 1.7 g/dL, and international normalized ratio of 1.11. Autoimmune antibody testing for fluorescence antinuclear antibody was negative. COVID-19 antigen swab test was negative.

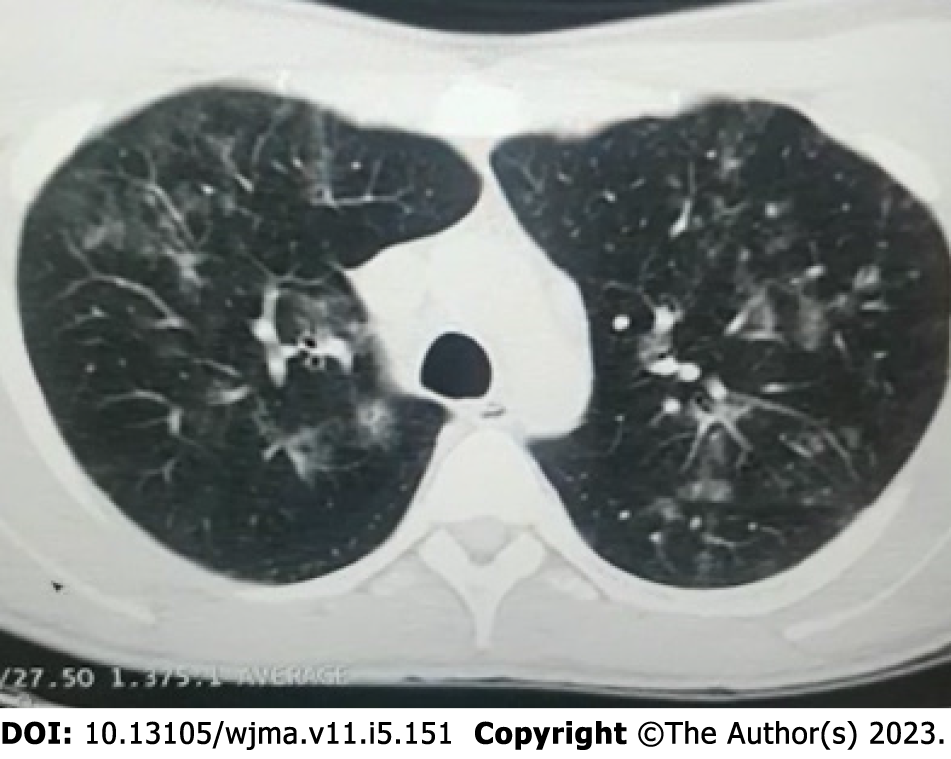

Imaging examinations: After a liver biopsy, the patient's results were suggestive of drug-induced liver injury, and subsequent immunochemistry testing returned negative results for CMV. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen showed a liver with enlarged dimensions, regular contours, and heterogeneous signal intensity, with predominance of hyper signal in the T2-weighted sequences, suggestive of an inflammatory process (hepatitis), and splenomegaly and pancreatic edema suggestive of pancreatitis. CT of the thorax showed GGOs (Figure 1), while CT of the face showed sinusitis.

Final diagnosis: The patient's clinical condition worsened, and he developed hypotension and sepsis, requiring admission to the ICU. Broad-spectrum antibiotics were started, and he was investigated for possible Wegener's granulomatosis. However, auto-antibodies were negative and his final diagnosis was disseminated CMV infection, confirmed by the high viral load of 325192.5 copies/mL.

Treatment: The patient was started on ganciclovir therapy.

Outcome and follow-up: After 6 wk of treatment, the patient recovered completely from his symptoms, achieving a sustained undetectable viral load.

This study followed the recommendations outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines[16].

The electronic database MEDLINE (PubMed) was searched using the terms described in the Supplementary material. The searches were conducted in September and October 2022, with no date of publication restrictions and language restricted to English. References of included studies were screened for relevant records, and the reference lists of the retrieved studies were submitted to a manual search.

Case report or case series studies were eligible for selection. If there was more than one study published using the same case, the most recent study was selected for analysis. Studies published only as abstracts were also included, as long as the data available made data collection possible. Studies written in languages other than English were excluded. Studies having other co-existing causes of pneumonia were excluded from our study, for example, superimposed bacterial, parasitic, or fungal infections in existing CMV pneumonia, and other lung pathologies.

Titles were screened initially to select the cases of pulmonary complications of CMV infection and filter out non-relevant studies. Then, abstracts of chosen studies were read to select potentially relevant papers. The third step was the analysis of the full-length papers, and those which were not case reports of pulmonary CMV were filtered out. Data was extracted on the characteristics of the subjects and the outcomes measured from each eligible study. A table of extracted data on eligible studies was made in order to measure and identify patterns.

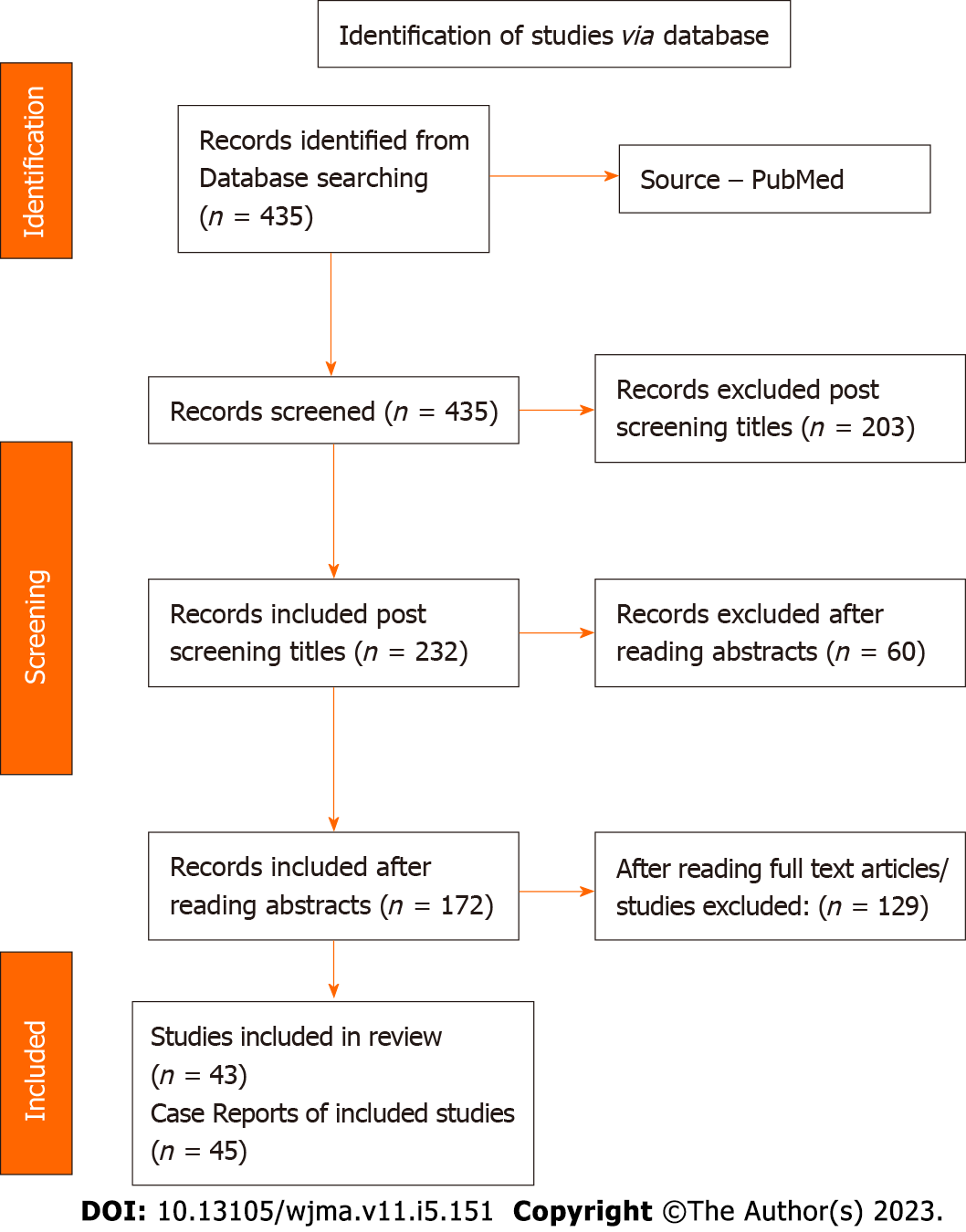

Using the search strategy, a total of 435 references were retrieved. After reviewing titles, 232 studies were found to be relevant for our topic and 203 studies were excluded. By analyzing abstracts, 172 studies were found to be potential relevant papers for our topic and therefore 60 studies were excluded. After reading and analyzing full length papers, 43 studies with 45 case reports of pulmonary CMV infection were included. The data of 45 case reports was extracted and prepared in Table 1 to measure and identify the patterns to get the results to reach a conclusion. Figure 2 shows the PRISMA search strategy. Every study included was a case report.

| Ref. | Age | Sex | Clinical findings | Immune status | Radiographic findings | Serology | Immunohistochemistry & biopsy | Treatment | Out-come |

| Luís et al[22], 2021 | 42 | M | Fever, headache, odynophagia, bilateral otalgia | Immunocompetent | CXR – B/L infiltrates; Thoracic CT – B/L GGO | Blood – CMV PCR positive; BAL fluid – CMV PCR positive | Ganciclovir and valganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Balakrishnan et al[23], 2022 | 41 | M | Fever, cough, weight loss | Immunocompromised; chronic glomerulo- nephritis, IgA nephropathy; on immunosuppressive drugs | CXR – B/L infiltrates; Thoracic CT – B/L GGO, patchy consolidation, nodular opacities | Blood – CMV PCR positive; BAL fluid – CMV PCR positive | Valganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Basinger et al[24], 2022 | 70 | M | Rapid decline in general condition, resp. distress | Immunocompromised; a history of allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplant | Rapidly progressive bilateral pulmonary nodules | Not done | Post mortem cytopatholog. Change, consistent with CMV infection, confirmed by IHC | Not initiated | Died |

| Gonçalves et al[2], 2018 | 29 | M | Fever, headache, malaise, cough, thoracic pleuritic pain | Immunocompetent | Thoracic CT showed bilateral infiltrates | Blood – positive for CMV IgG and IgM; BAL – CMV PCR was positive | Ganciclovir and valganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Wong et al[25], 2022 | 37 | M | Fever, cough, dyspnea | Immunocompromised; X-linked agammaglobulinemia is a hereditary immune disorder | CMV positive | Antiviral and immune globulin therapy | Recovery | ||

| Gangemi et al[26], 2021 | 72 | M | Non-healing buccal ulcer, fever, acute hypoxic respiratory failure, worsening odynophagia, weight loss | Immunocomromised; oropharyngeal Ca in remission | Chest X-ray – patchy opacities of B/L lung fields; Thoracic CT – bilateral upper and lower lobe consolidations, B/L pleural effusions | Positive for both CMV IgG and IgM | Ganciclovir and valganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Patil et al[27], 2020 | 23 | F | Worsening dyspnea, high grade fever, dry cough | Immunocompetent | Chest X-ray – mild bilateral interstitial infiltrates with small bilateral pleural effusions; CT chest - worsening of bilateral interstitial infiltrates | BAL CMV PCR and blood CMV PCR positive | Ganciclovir and valganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Alyssa et al[28], 2017 | 63 | F | Fever, hypotension, dyspnoea on exertion, hypoxemia, weakness | Immunocompromised; diagnosis of dermatomyositis - history of prolonged use of glucocorticoids and treatment with rituximab | CT chest - bilateral GGOs in a mosaic distribution and consolidations of B/L lower lobes | CMV DNA PCR quantitation in whole blood was positive and shell-vial culture for CMV positive | Ganciclovir and valganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Fragkiadakis et al[29], 2018 | 36 | F | Fever, respiratory distress | Immunocompromised; undergone multiple transfusions, and splenectomy was done for homozygous β-thalassemia | CT chest demonstrated pneumonitis | Serology and molecular blood testing reports – CMV infection and viremia | Ganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Waqas et al[30], 2019 | 36 | M | Fever, cough, malaise | Immunocompetent | CXR – B/L infiltrates | Diagnosed with CMV infection | Ganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Xie et al[31], 2021 | 22 | M | Fever, progressive dyspnea, dry cough | Immunocompromised; newly diagnosed HIV infection | Chest CT – extensive GGOs of bilateral lungs with multiple cavity lesions in the left upper lung | CMV quantitative PCR positive | Ganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Al-Eyadhy et al[32], 2017 | 12 | M | Tachycardia, tachypnea, fever, severe ARDS with multi-organ failure | Immunocompetent; CMV infection associated morbidity and mortality among immune-competent children | CXR and chest CT – ARDS features | CMV PCR positive in blood | HPE of lung biopsy CMV positive | Ganciclovir | Recovery |

| Reesi et al[33], 2014 | 3 | M | Fever, dyspnea | Immunocompromised; acute lymphoblastic leukaemia on chemotherapy | CXR - pulmonary infiltrates; CT chest - diffuse GGOs of B/L lung fields, few pleural-based nodules | BAL CMV PCR was positive; CMV IgG and IgM positive | Ganciclovir and valganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Cunha et al[34], 2008 | 64 | M | “Flu-like illness”, fever, myalgias, progressive dyspnoea, and required mechanical ventilation | Immunocompetent; slowly improved over 14 d and was eventually extubated | Chest X-ray showed B/L interstitial markings that rapidly progressed over 24 h | Initially IgG, IgM and CMV PCR negative; 10 d later, IgG, IgM, and CMV PCR were positive | BAL cytology was negative for viral inclusions | Did not receive CMV antiviral therapy | Recovery |

| Demirkol et al[35], 2018 | 2 | M | Respiratory distress, fever, multiple organ dysfunction secondary to sepsis | Immunocompetent; developed necrotizing pneumonia | Thoracic CT – features of necrotising pneumonia | Serological tests indicated that the patient had CMV reactivation | Excised lung tissue, features of CMV infection | Ganciclovir | Recovery |

| Margery et al[36], 2009 | 43 | F | Fever, dyspnoea | Immunocompetent | Thoracic CT – diffuse GGOs | Anti-CMV IgM and PCR detection of viral DNA in serum | Not treated | Recovery | |

| Bansal et al[37], 2012 | 45 | F | Nausea and vomiting. CMV infection can present with only atypical symptoms in liver transplant patients | Immunocompromised; liver transplant due to anti- tubercular drug induced acute liver failure | CXR showed B/L infiltrates | Testing of CMV viral load showed a viral load of 9640 copies/mL | Ganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Sunnetcioglu et al[38], 2016 | 24 | M | Cough, fever dyspnoea, haemoptysis, shortness of breath, and was intubated | Immunocompromised; on immunesuppressive therapy for polyarteritis nodosa | Chest X-ray showed right-sided opacity in the middle and lower lung zones Thoracic CT showed B/L alveolar opacity | Positive test for serum CMV IgM antibodies | NA | NA | |

| Liatsos et al[39], 2017 | 40 | F | Acutely ill with fever, dry cough, and mild shortness of breath | Immunocompromised; β-thalassemia major with splenectomy, regularly transfused with packed and leukocyte-depleted red blood cells | Thoracic CT - B/L interstitial lung infiltrates and small nodules marked toward the lower lobes, with a few ground-glass areas and bilateral pulmonary effusions | Positive RT-PCR for CMV in both blood and BAL | Ganciclovir and valganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Wickramasinghe et al[40], 2022 | 32 | M | Headache, fever, cough, and shortness of breath. The patient was in respiratory distress, shifted to ICU and electively intubated | Immunocompromised; Tuberculosis meningitis | Chest X-ray showed left-sided consolidation. CT chest revealed lower lobe (left more than right) consolidation and nodules | Positive CMV IgM and negative IgG, suggesting acute infection | Antitubercular drugs and ganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Barclay et al[41], 2011 | 38 | F | Fever and non-specific symptoms & increasingly hypoxaemic | Immunocompetent | Thoracic HRCT showed diffuse multilobular ground glass appearance with peripheral nodular opacities | CMV IgM antibody was positive and CMV PCR was positive | Valganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Coussement et al[42], 2016 | 64 | F | Fever, cough, dyspnea, hypoxemia | Immunocompromised; bilateral lung transplant for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Thoracic CT demonstrated bilateral infiltrates; abdominal CT showed peri-colic infiltration compatible with a recurrence of diverticulitis | CMV VL observed both in blood and BAL samples; a diagnosis of CMV pneumonitis using BAL sample; a macrophage characteristic of CMV viral infection | Resected colon revealed HPE CMV colitis, viral inclusions, and positive immunohistochemistry | Ganciclovir | Recovery |

| Kanhere et al[43], 2014 | 3 1/2 | M | Fever, respiratory distress, hepatosplenomegaly | Immunocompromised; hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis | CMV IgM serology was reactive in both infant and mother | Ganciclovir | Recovery | ||

| Suresh et al[44], 2013 | 7/12 | M | Cough, dyspnoea, respiratory distress, progressive increase in oxygen requirement | Immunocompetent | Chest XR -prominent bronchovascular markings | CMV IgM serology was positive and CMV PCR based on BAL was also positive | Ganciclovir and valganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Suresh et al[44], 2013, Case 2 | 3/12 | F | Cough, dyspnoea, respiratory distress, progressive increase in oxygen requirement | Immunocompetent | CXR normal | CMV IgM blood was raised; BAL positive for CMV PCR | Ganciclovir and valganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Yu et al[45], 2017 | 64 | M | Acute respiratory failure with renal failure | Immunocompromised; diabetic; severe CMV pneumonia with slow resolution or persistent viremia on treatment | Chest X-ray -predominately right lung infiltrates; chest CT showed multiple consolidative patches with air bronchograms | Positive CMV PCR in blood and BAL | Lung biopsy was done. Inclusion bodies, positive for CMV IHC | Ganciclovir and valganciclovir | Died |

| Tollitt et al[46], 2016 | 71 | F | Hemoptysis | Immunocompromised; antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis; on therapy with cyclophosphamide, steroids, and plasma exchange | Pulmonary CMV disease mimics pulmonary disease associated with vasculitis on CXR | BAL demonstrated positivity for CMV DNA and serum CMV PCR positive | Ganciclovir and valganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Vetter et al[47], 2010 | 70 | F | Fever, nausea, dyspnea | Immunocompromised; immunosuppressive therapy with methotrexate and prednisone for large-vessel vasculitis | Chest X-ray showed no interstitial pneumonitis; chest and abdominal CT showed no signs of inflammation | CMV IgG and IgM antibodies positive; CMV PCR positive in BAL fluid | Ganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Snape et al[48], 2011 | 28 | F | Fever, cough tender sinuses, frontal headache | Immunecompetent | CXR showed consolidation of the middle and right upper lobe; Pulmonary CT angiography revealed no pulmonary embolus and patchy consolidation of B/L lungs | Positivity for CMV IgM | Valganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Karakelides et al[49], 2003 | 47 | M | Cough, hemoptysis, weight loss | Immunocompetent | CXR and chest CECT showed a 3.5-cm cavitary mass, upper lobe of left lung and mild left mediastinal and hilar adenopathy | Transbronchial biopsy - CMV inclusions | Wedge excision of left upper lung mass; HPE -nuclear & cytoplasmic inclusions of CMV | NR | Recovery |

| Shimada et al[50], 2004 | 27 | F | Fever | Immunocompromised; on immunosuppressive treatment for viral-associated hemophagocytic syndrome | CXR and chest HRCT – diffuse small pulmonary nodules | CMV DNA PCR was positive on bronchoalveolar lavage cells; immunoassay pp65 CMV antigen positive | Lung biopsy inclusion-bearing cells for CMV | Gancyclovir | Recovery |

| Simsir et al[51], 2001 | 43 | M | Malaise, fever, pleuritic chest pain, epigastric pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting | Immunocompromised; underwent renal transplant secondary to diabetic nephropathy | CXR showed a nodule in the upper lobe of the right lung; chest CT revealed bilateral smaller pulmonary nodules | CMV antigen test was positive, with negative CMV IgG | CMV was established by fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the lung nodule | Gancyclovir | Recovery |

| Abbey et al[52], 2014 | 51 | M | Fever, dry, cough, dyspnoea, general malaise | Immunocompromised; Crohn’s disease on azathioprine; also had mild pancreatic insufficiency and bile salt malabsorption | CXR showed bilateral infiltrates in middle and lower zones; chest CT showed B/L small pleural effusions and B/L basal lung consolidation | CMV IgM positive, acute CMV infection | Ganciclovir and valganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Belin et al[53], 2003 | 47 | F | Shortness of breath, fever, stomatitis, genital ulcerations, burning sensations | Immunocompromised; severe rheumatoid arthritis, on prednisolone, methotrexate, and cyclosporine | CXR showed interstitial infiltrates in both lung bases | BAL showed CMV mRNA | Ganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Kaşifoğlu et al[54], 2006 | 21 | F | Polyarthralgias, fatigue, fever, muscle weakness, non-productive cough, dyspnea | Immunocompromised; dermatomyo-sitis, treated with azathioprine, prednisolone, and cyclosporine | Chest XR showed bilateral interstitial infiltration; chest HRCT - bilaterally ill-defined multifocal GGOs | Positivity for anti-CMV, IgM, and anti-CMV IgG antibodies and presence of CMV DNA by PCR | Ganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Chen et al[55], 2010 | 5 | M | Fever, cough, dyspnea, hypoxemia, ARDS | Immunocompetent; the patient developed ventilator-associated pneumonia, and died of burkhoderia sepsis | Chest XR – multiple parenchymal consolidations; chest XR disclosed “white lung” during the second week | Positive PCR; bronchoalveolar and seroconversion of CMV IgM and IgG | NR | Died | |

| Tambe et al[56], 2019 | 32 | F | Fever, dyspnea, generalized rash, weakness | Immunocompromised; stage IV, classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma, treated with chemotherapy | Chest CT revealed bilateral pulmonary infiltrates and bilateral pleural effusion | CMV was detected on BAL culture; serum quantitative CMV PCR was positive | Ganciclovir and valganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Boussouar et al[57], 2018 | 47 | F | Dry cough, chest pain and fever | Immunocompromised; orthotopic heart transplant and immunosuppressive treatment was initiated with corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate | Chest XR - alveolar opacities with upper lobe predominance; chest CT revealed consolidation in the right upper lobe associated with septal thickening and multiple nodules | Blood CMV PCR, which has been undetectable | Lung biopsy showed nuclear inclusions suggestive of CMV infection; IHC showed nuclear positivity for CMV | Ganciclovir and valganciclovir | Recovery |

| Haddad et al[58], 1984 | 18 | M | Fever, chills, non-productive cough, severe hypoxia requiring intubation | Immunocompromised; sickle cell thalassemia | Chest XR suggested early pulmonary edema and cardiomegaly | On postmortem culture of lung parenchyma, CMV grew in 5 d | NR | Died | |

| Katagiri et al[59], 2008 | 35 | F | Deterioration of lupus nephritis and received treatment with a high dose of steroid and cyclosporine | Immunocompromised; SLE with increased risk of opportunistic infection | Chest X-ray showed bilateral pleural effusion; chest CT revealed a cavitary lesion in the right middle lobe of the lung | Positive for CMV; antigenemia | Ganciclovir | Recovery | |

| Ayyappan et al[60], 2006 | 72 | M | Fever, productive cough, worsening breathlessness and tenderness in epigastrium | Immunocompromised; rheumatoid arthritis-related interstitial lung disease, on corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide | Chest XR showed bilateral consolidation; chest CT revealed cavitating masses in the right upper lobe & lingula and diffuse interstitial fibrosis | PCR assay of BAL fluid was positive for CMV | Gastric biopsy - intracytoplasmic viral inclusions consistent with CMV gastritis; transbronchial lung biopsy showed intracytoplasmic viral inclusion | Gancyclovir | Recovery |

| Manian et al[61], 1993 | 32 | F | Fever, non-productive cough, worsening oxygenation | Immunocompetent | Chest X ray - bilateral interstitial infiltrates | Enzyme immune-assay showed that CMV IgG and CMV IgM were positive | Ganciclovir | Recovery | |

| McCormack et al[62], 1998 | 31 | M | Fever, abdominal pain, jaundice, cough, palpitations, shortness of breath with atrial fibrillation | Immunocompetent | Chest radiograph showed bilateral interstitial pulmonary infiltrates | EIA for antibodies to CMV showed a strong reaction to IgM and a weak reaction to IgG | A urine culture yielded CMV; a cytopathic effect was observed and con-firmed by immunofluorescence | Ganciclovir | Recovery |

| Najjar et al[63], 2004, Case 1 | 34 | F | Fever | Immunocompromised; SLE with renal failure on haemodialysis | Chest XR - bilateral infiltrates; chest CT - bilateral peripheral parenchymal infiltrates and a cavitating mass in right lower lobe | A CMV antigenaemia assay was positive and CMV isolation in blood | Histological findings included numerous intranuclear and intracytoplasmic CMV inclusions confirmed by IHC | IV ganciclovir and IV IgG | Recovery |

| Najjar et al[63], 2004, Case 2 | 33 | M | Fever, dyspnoea, worsening renal function | Immunocompromised; SLE, class IV lupus, nephritis treated with chronic steroid therapy, azathioprine, and cyclophosphamide | Chest CT revealed a right upper lobe thick-walled cavitary lesion | Serology revealed raised CMV IgM & IgG | HPE - evidence of focal interstitial fibrosis, accumulation of intraalveolar macrophages, and CMV with intracytoplasmic and nuclear inclusions in the lining alveolar cells | Gancyclovir | Recovery |

| Kanika et al | 32 | M | Fever, dyspneia, hypotension, jaundice | Immunocompetent | MRI showed hepatitis and pancreatitis; CT showed GGO | Serum PCR with a high viral load | Liver biopsy suggestive of drug induced liver injury and immunochemistry negative for CMV | Ganciclovir | Recorvery |

The baseline features are described in Table 2 and Table 3 for the 45 patients who were included for data extraction. All patients were diagnosed with CMV pneumonia. The majority of patients were males (58%) and in the age group of 16-45 years (55.6%). The most common symptoms reported were fever (82%), dyspnea (76%), and cough (53%). Respiratory distress was observed in 58% of the patients. Almost two-thirds of the patients (64%) were immunocompromised. Radiographic findings were reported in 71% of the patients by chest X-ray and 69% by CT. Blood/serum was the most commonly used method for serology testing (89%), and bronchoalveolar fluid was used in 45% of the cases.

| Variable | Patients, n = 45 (100%) |

| Age group | |

| 0–15 yr | 7 (15.6) |

| 16–45 yr | 25 (55.6) |

| 46–75 yr | 13 (28.8) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 26 (58) |

| Female | 19 (42) |

| Symptoms | |

| Fever | 37 (82) |

| Cough | 24 (53) |

| Dyspnoea | 34 (76) |

| Resp. distress | 26 (58) |

| Immune status | |

| Immunocompetent | 16 (36) |

| Immunocompromised | 29 (64) |

| Radiograhic findings | |

| Chest X-ray | 32 (71) |

| Thoracic CT | 31 (69) |

| Serology | |

| Blood/serum | 40 (89) |

| Bronchoalveolar fluid (BAL) | 18 (45) |

| Specific tests | |

| Immunohistochemistry | 11 (24) |

| Biopsy - histopathology | 12 (27) |

| Treatment | 38 (84) |

| Recovery | 40 (89) |

| Died | 4 (9) |

| Immunocompetent | Immunocompromised | |

| Total | 16 | 29 |

| Fever | 13 | 24 |

| Cough | 11 | 13 |

| Dyspnoea | 12 | 22 |

| Respiratory distress | 10 | 16 |

| Treatment | 12 | 26 |

| Recovered | 15 (94%) | 25 (86%) |

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was reported in 24% of the cases, and biopsy-histopathology was performed in 27% of the patients. The treatment was reported in 84% of the cases, with a high recovery rate of 89%. Unfortunately, the mortality rate was 9%, with four patients reported to have died.

This paper analyzed 45 cases of CMV-induced pneumonia. Patients were divided into two main categories: Immunocompetent and immunocompromised. Twenty-nine (64%) patients were immunocompromised, and 16 (36%) were immunocompetent and developed CMV pneumonia. This suggests that CMV infection prevalence is higher in immunocompromised patients[2]. The reported case highlights the importance of considering CMV infection in patients who present with fever, respiratory symptoms, and abnormal liver function tests. Although CMV infection is more common in immunocompromised patients, this case demonstrates that it can also occur in immunocompetent individuals. It is important to note that CMV is a common cause of pneumonia, particularly in immunocompromised patients, and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with respiratory symptoms who do not respond to standard treatment. Early diagnosis and treatment are essential in improving patient outcomes, especially in severe cases. Therefore, clinicians should be aware of the clinical features and radiological findings of CMV pneumonia to enable early diagnosis and appropriate management[17-20].

The differential diagnosis of this case includes severe COVID-19 infection, which shares some clinical features with CMV pneumonia, such as cough, dyspnea, and fever. However, some features of the case, such as jaundice, hepatosplenomegaly, and pancytopenia, are not typically seen in severe COVID-19 cases. Additionally, GGOs on CT imaging can be seen in both CMV pneumonia and COVID-19. Therefore, it is important to consider other infectious and non-infectious etiologies in patients with respiratory symptoms and abnormal liver function tests.

A systematic review was performed a total of 45 patients, of which 26 (58%) were male and 19 (42%) were female. Infection was more prevalent in males, with 11 immunocompetent and 15 immunocompromised male patients and 5 immunocompetent and 14 immunocompromised female patients. This suggests that CMV infection is more prevalent in immunosuppressed patients in both males and females. Immunocompromised states are an important host-associated risk factor to get CMV infection[2].

Regarding age, 25 patients were adults (13 males and 12 females), indicating that the adult population is more prone to developing pulmonary CMV infection. As it is estimated that more than half of the adult population are infected with CMV in the United States, and 80% of the adult population have this infection by the age of 40 years, the prevalence of CMV-induced pneumonia may increase with age[1]. The clinical findings of most patients were fever (82%), dyspnea (75%), cough (53%), and respiratory distress (53%) in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients. These findings are consistent with previous studies on CMV pneumonia[4].

Regarding radiological findings, 32 patients were submitted to a chest X-ray mostly showing bilateral diffuse pulmonary infiltrates. CT of the thorax was done in 31 patients, and the main finding was bilateral GGOs. In some patients, there were small bilateral pulmonary nodules, confluent consolidations, and bronchiectasis. In case of atypical radiological findings other than bilateral infiltrates and GGOs, further investigation, such as blood and BAL serology, lung biopsy histopathological examination (HPE), and IHC, should be considered to rule out CMV pneumonia[7].

Blood serology was done in 40 (89%) patients, and IgM and IgG were positive for CMV. Other tests, such as BAL fluid serology, lung biopsy histopathology, and IHC, were done to confirm the diagnosis in some patients. IgM CMV positive in blood represents acute CMV infection, and antiviral treatment was given to the patients with a successful outcome[2,5].

A study by Basinger et al[24] demonstrated that immunocompromised states, particularly those with a history of allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplant, can result in rapidly deteriorating conditions and respiratory status post-CMV infection. Radiologically, patients may present with rapidly progressive bilateral pulmonary nodules approximately 2 mo after receiving a bone marrow transplant. This patient died shortly after admission, and the diagnosis was made on post-mortem microscopic examination of the pulmonary nodules that demonstrated viral cytopathologic changes consistent with CMV infection, confirmed by IHC. It is essential to note that the radiographic presentation is not always GGOs, and rapidly enlarging pulmonary nodules in an immunosuppressed patient are highly suggestive of an infectious process. Therefore, careful histologic examination for viral cytopathologic changes is essential[3].

Regarding treatment, 38 (85%) patients received antiviral therapy, and 2 patients recovered without receiving antiviral treatment. In total, 89% of patients recovered, indicating that the prognosis of CMV pneumonia is good if diagnosed early and treated in time, in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients[2]. A study by Al-Eyadhy et al[32] in 2017 presented the case of a 12-year-old immunocompetent patient who was admitted with severe ARDS and developed multi-organ failure, which is an important differential diagnosis from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Due to the correct diagnosis and treatment of CMV infection in time, the patient recovered. Another study by Coussement et al[42] in 2016 showed that a 63-year-old immunocompromised patient who did a bilateral lung transplant for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease admitted with severe CMV infection and due to timely diagnosis and antiviral treatment, the patient recovered well.

In immunocompetent patients, the recovery rate was 94%, while in immunocompromised patients, it was 86%. The study showed that there were four deaths, three of which were among immunocompromised patients. This suggests that immunocompromised patients may develop more severe CMV illness that deteriorates quickly, sometimes making it challenging to make a timely diagnosis. Therefore, it is crucial to consider CMV infection as one of the important differentials in immunocompromised patients[1,4].

The final result of this analysis showed that 89% of total patients recovered, indicating that the prognosis of CMV pneumonia is good if patients are diagnosed early and treated promptly, even for immunocompromised patients[1,4].

To reach a definitive diagnosis, clinical findings must be correlated with imaging tests and laboratory tests. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is the most sensitive method of detecting CMV, and qRT-PCR can be used to quantify viral loads in blood and BAL fluid. BAL CMV-PCR is considered the most accepted approach for viral isolation in the lungs due to its high sensitivity. Lung biopsy histopathology is considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of pulmonary CMV infections, and the presence of CMV inclusions in the HPE report is confirmatory of lung infection. Additionally, CMV can be detected by IHC staining for CMV in cytologic specimens of bronchial lavage fluid[1,2].

In critically ill patients, CMV infection is associated with prolonged mechanical ventilation, nosocomial infections, prolonged hospital and ICU stay, and increased mortality. The first-line treatment for CMV disease is intravenous ganciclovir and its prodrug, oral valganciclovir. Mild disease in immunosuppressed patients may be treated with oral valganciclovir, while severe illness is treated with IV ganciclovir or foscarnet at full doses (adjusted for renal function), followed by valganciclovir. Treatment at full doses should be continued until the resolution of symptoms and blood antigenemia (or DNAemia) is cleared. The prognosis of CMV pneumonia is good if patients are diagnosed and treated at an early stage[1,2,4]. This systematic review aimed to understand the pattern, presentations, clinical course, and outcome of patients with COVID-19 and CMV coinfection and analyzed data from 34 reports with 59 patients. The results showed that middle-aged and elderly patients with comorbidities were more susceptible to coinfection, and CMV colitis was the most common manifestation of end-organ involvement. The findings of this study may assist in detecting and treating patients with unusual clinical courses or severe, prolonged, or unexplained deterioration of end-organ function[64].

In conclusion, CMV pneumonia is a serious complication in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients, with a higher morbidity and mortality rate in the former group. The diagnosis of CMV pneumonia can be challenging as it may present with nonspecific clinical and radiological features similar to COVID-19 pneumonia. Therefore, it is crucial to consider CMV infection as a differential diagnosis in immunocompromised patients with respiratory symptoms. Early diagnosis and treatment with antiviral therapy can lead to a good prognosis, while delayed diagnosis and treatment can lead to a more severe illness and potentially fatal outcomes. Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for CMV pneumonia in immunocompromised patients and perform appropriate diagnostic tests, such as PCR and histopathological examination. Further research is needed to better understand the pathogenesis, risk factors, and optimal management of CMV pneumonia.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a DNA virus that can cause severe disease in immunocompromised patients and is common in recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. CMV is acquired through direct contact with infected cells or body fluids, and transmission can occur from a CMV-seropositive donor organ. Congenital CMV, transmitted from infected mothers to their newborns, is a leading cause of miscarriage. CMV is one of the three most common causes of severe viral community-acquired pneumonia, but this has changed with the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in 2020.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to differentiate clinical and radiological presentations from other diseases. Ground-glass opacities (GGOs) require evaluation along with other tests to reach a diagnosis. To diagnose CMV pneumonia, the virus can be detected in serum or respiratory samples, and quantitative real-time PCR can measure viral loads in blood and BAL fluid. Lung biopsy histopathology is the gold standard for diagnosing pulmonary CMV infections. However, the diagnostic yield of lung biopsy varies, and the study of CMV pneumonia in immunocompetent patients with GGOs remains limited.

This study aimed to report a case of CMV pneumonia in an immunocompetent patient with GGOs on chest CT, to review the literature on the clinical, radiological, and laboratory features of CMV pneumonia in immunocompetent hosts, and to discuss the diagnostic workup and management of CMV pneumonia.

This study followed PRISMA guidelines to identify case reports and case series studies on pulmonary complications of CMV infection. The selection criteria included studies that reported only CMV pneumonia without other co-existing causes of pneumonia. Data extraction involved identifying the characteristics of the subjects and the outcomes measured. The patient case report presented in the article was included in the study as it met the inclusion criteria, and the patient received ganciclovir therapy resulting in complete recovery from symptoms and sustained undetectable viral load after 6 wk of treatment.

The study found 45 case reports of pulmonary CMV infection after analyzing 435 references. The majority of the patients were males (58%) in the age group of 16-45 years (55.6%). Common symptoms included fever, dyspnea, and cough, with respiratory distress observed in 58% of the cases. Most patients (64%) were immunocompromised. Radiographic findings were reported in 71% of the patients, and blood/serum was the most commonly used method for diagnosis. Treatment was reported in 84% of the cases, with a high recovery rate of 89%, but the mortality rate was 9%. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment are crucial to improve outcomes and reduce mortality rates, especially in immunocompromised individuals.

The study analyzed 45 cases of CMV-induced pneumonia and found that it can occur in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients, with clinical findings of fever, dyspnea, cough, and respiratory distress. Radiological findings showed bilateral diffuse pulmonary infiltrates and bilateral GGOs. Blood serology was positive for CMV, and antiviral treatment was given with a successful outcome. The recovery rate was high, but four deaths were reported, with three among immunocompromised patients.

Future studies can investigate the prevalence of CMV pneumonia in different age groups and genders, and the possible link between CMV and COVID-19. The effectiveness of antiviral therapy in preventing severe CMV illness and the optimal duration of treatment can be evaluated. Pathophysiology and immunology of CMV pneumonia in immunocompromised patients need further research.

We would like to extend our sincere appreciation to the Acute Medicine MSc program at the University of South Wales for their invaluable assistance in our work. We acknowledge and commend the University of South Wales for their commitment to providing advanced problem-solving skills and life-long learning opportunities for healthcare professionals.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Infectious diseases

Country/Territory of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: IKram A, Pakistan; Pozzetto B, France, Tavan H, Iran S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Sandra Gonzalez Gompf, Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Infection, Infectious Disease HealthCenter, May 5, 2022. Available from: https://www.medicinenet.com/cytomegaloviruscmv/article.htm. |

| 2. | Gonçalves C, Cipriano A, Videira Santos F, Abreu M, Méndez J, Sarmento E Castro R. Cytomegalovirus acute infection with pulmonary involvement in an immunocompetent patient. IDCases. 2018;14:e00445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Rohit Sharma. Cytomegalovirus pulmonary infection, June 13, 2022. Available from: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/cytomegalovirus-pulmonary-infection-1. |

| 4. | Yang Y, Xiao Z, Ye K, He X, Sun B, Qin Z, Yu J, Yao J, Wu Q, Bao Z, Zhao W. SARS-CoV-2: characteristics and current advances in research. VirologyJournal, Article number: 117 (2020). July 29, 2020. Available from: https://virologyj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12985-020-01369-z. |

| 5. | Cunha BA. Cytomegalovirus pneumonia: community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent hosts. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2010;24:147-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Lanzieri TM, Dollard SC, Bialek SR, Grosse SD. Systematic review of the birth prevalence of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in developing countries. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;22:44-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Kaplan JE. Cytomegalovirus (CMV), June 27, 2020. Available from: https://www.webmd.com/hiv-aids/guide/aids-hiv-opportunistic-infections-cytomegalovirus. |

| 8. | Cedeno-Mendoza R. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Clinical Presentation Jul 07, 2021. Available from: https://www.medscape.com/answers/215702-99966. |

| 9. | Florescu DF, Kalil AC. Cytomegalovirus infections in non-immunocompromised and immunocompromised patients in the intensive care unit. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2011;11:354-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Pontolillo M, Falasca K, Vecchiet J, Ucciferri C. It is Not Always COVID-19: Case Report about an Undiagnosed HIV Man with Dyspnea. Curr HIV Res. 2021;19:548-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | CMV Infection Laboratory Testing| CDC. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/cmv/clinical/Lab-tests.html. |

| 12. | Restrepo-Gualteros SM, Gutierrez MJ, Villamil-Osorio M, Arroyo MA, Nino G. Challenges and Clinical Implications of the Diagnosis of Cytomegalovirus Lung Infection in Children. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2019;21:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Govender K, Jeena P, Parboosing R. Clinical utility of bronchoalveolar lavage cytomegalovirus viral loads in the diagnosis of cytomegalovirus pneumonitis in infants. J Med Virol. 2017;89:1080-1087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Lee HY, Rhee CK, Choi JY, Lee HY, Lee JW, Lee DG. Diagnosis of cytomegalovirus pneumonia by quantitative polymerase chain reaction using bronchial washing fluid from patients with hematologic malignancies. Oncotarget. 2017;8:39736-39745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tan BH. Cytomegalovirus Treatment. Curr Treat Options Infect Dis. 2014;6:256-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med. 2009;3:e123-e130. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Matos MJR, Rosa MEE, Brito VM, Amaral LTW, Beraldo GL, Fonseca EKUN, Chate RC, Passos RBD, Silva MMA, Yokoo P, Sasdelli Neto R, Teles GBDS, Silva MCBD, Szarf G. Differential diagnoses of acute ground-glass opacity in chest computed tomography: pictorial essay. Einstein (Sao Paulo). 2021;19:eRW5772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Colomba C, Lalicata F, Siracusa L, Saporito L, Di Bona D, Giammanco G, De Grazia S, Titone L. [Cytomegalovirus infection in immunocompetent patients. Clinical and immunological considerations]. Infez Med. 2012;20:12-15. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Georgakopoulou VE, Mermigkis D, Melemeni D, Gkoufa A, Damaskos C, Garmpis N, Garmpi A, Trakas N, Tsiafaki X. Cytomegalovirus pneumonia in an immunocompetent host with primary ciliary dyskinesia: A case report. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2021;91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | McGuinness G, Scholes JV, Garay SM, Leitman BS, McCauley DI, Naidich DP. Cytomegalovirus pneumonitis: spectrum of parenchymal CT findings with pathologic correlation in 21 AIDS patients. Radiology. 1994;192:451-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tamm M, Traenkle P, Grilli B, Solèr M, Bolliger CT, Dalquen P, Cathomas G. Pulmonary cytomegalovirus infection in immunocompromised patients. Chest. 2001;119:838-843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Luís H, Barros C, Gomes M, Andrade JL, Faria N. Cytomegalovirus Pulmonary Involvement in an Immunocompetent Adult. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2021;2021:4226386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Balakrishnan R, Padmanabhan A, Ameer KA, Arjun R, Muralidharan P. Cytomegalovirus pneumonitis in an immunocompromised host. Lung India. 2022;39:202-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Basinger J, Kapp ME. Cytomegalovirus pneumonia presenting as pulmonary nodules. Autops Case Rep. 2022;12:e2021362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wong YX, Shyur SD. Cytomegalovirus Pneumonia in a Patient with X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia: A Case Report. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gangemi AC, Choi SH, Yin Z, Feurdean M. Cytomegalovirus and Herpes Simplex Virus Co-Infection in an HIV-Negative Patient: A Case Report. Cureus. 2021;13:e13214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Patil SM, Beck PP, Patel TP, Hunter MP, Johnson J, Acevedo BA, Roland W. Cytomegalovirus pneumonitis-induced secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and SIADH in an immunocompetent elderly male literature review. IDCases. 2020;22:e00972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Letourneau AR, Price MC, Azar MM. Case 26-2017. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:770-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Fragkiadakis K, Ioannou P, Papadakis JA, Hatzidakis A, Gikas A, Kofteridis DP. Cytomegalovirus Pneumonitis in a Patient with Homozygous β-Thalassemia and Splenectomy. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2018;71:370-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Waqas QA, Abdullah HMA, Khan UI, Oliver T. Human cytomegalovirus pneumonia in an immunocompetent patient: a very uncommon but treatable condition. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Xie Y, Ruan B, Jin L, Zhu B. Case Report: Next-Generation Sequencing in Diagnosis of Pneumonia Due to Pneumocystis jirovecii and Cytomegalovirus in a Patient With HIV Infection. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:653294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Al-Eyadhy AA, Hasan G, Bassrawi R, Al-Jelaify M, Temsah MH, Alhaboob A, Al-Sohime F, Alabdulhafid M. Cytomegalovirus associated severe pneumonia, multi-organ failure and Ganciclovir associated arrhythmia in immunocompetent child. J Infect Chemother. 2017;23:844-847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Reesi MA, Al-Maani A, Paul G, Al-Arimi S. Primary Cytomegalovirus-Related Eosinophilic Pneumonia in a Three-year-old Child with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia: Case report and literature review. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2014;14:e561-e565. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Cunha BA, Pherez F, Walls N. Severe cytomegalovirus (CMV) community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in a nonimmunocompromised host. Heart Lung. 2009;38:243-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Demirkol D, Kavgacı U, Babaoğlu B, Tanju S, Oflaz Sözmen B, Tekin S. Cytomegalovirus reactivation in a critically ill patient: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12:163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Margery J, Lefebvre N, Dot JM, Gervaise A, Andriamanantena D, Dieudonné M, Girodeau A. [Pulmonary involvement in the course of cytomegalovirus infection in an immunocompetent adult]. Rev Mal Respir. 2009;26:53-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Bansal N, Arora A, Kumaran V, Mehta N, Varma V, Sharma P, Tyagi P, Sachdeva M, Kumar A. Atypical presentation of cytomegalovirus infection in a liver transplant patient. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2011;1:207-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Sunnetcioglu A, Sunnetcioglu M, Emre H, Soyoral L, Goktas U. Cytomegalovirus pneumonia and pulmonary haemorrhage in a patient with polyarteritis nodosa. J Pak Med Assoc. 2016;66:1484-1486. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Liatsos GD, Pirounaki M, Lazareva A, Kikezou G, Dourakis SP. Cytomegalovirus infection in a splenectomized with β-thalassemia major: immunocompetent or immunosuppressed? Clin Case Rep. 2017;5:1063-1066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Wickramasinghe S, Tillekeratne M, Wijayawardhana S, Sadikeen A, Priyankara D, Edirisooriya M, Fernando A. Cytomegalovirus pneumonia in a background of central nervous system tuberculosis. Respirol Case Rep. 2022;10:e01002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Barclay A, Naseer R, McGann H, Clifton I. Cytomegalovirus pneumonia in an immunocompetent adult: a case report. Acute Med. 2011;10:197-199. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Coussement J, Steensels D, Nollevaux MC, Bogaerts P, Dumonceaux M, Delaere B, Froidure A. When polymerase chain reaction does not help: cytomegalovirus pneumonitis associated with very low or undetectable viral load in both blood and bronchoalveolar lavage samples after lung transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2016;18:284-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kanhere S, Bhagat M, Kadakia P, Joshi A, Phadke V, Chaudhari K. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with cytomegalovirus infection in an immunocompetent infant: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge! Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2014;30:299-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Suresh N, Thiruvengadam V. Ganciclovir therapy in two immunocompetent infants with severe acquired CMV pneumonitis. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2013;33:46-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Yu WL, Chen CM, Lee WY. Ventilator-associated cytomegalovirus organizing pneumonia in an immunocompetent critically ill patient. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2017;50:120-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Tollitt J, O'Riordan E, Poulikakos D. CMV disease complicating induction immunosuppressive treatment for ANCA-associated vasculitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Vetter M, Battegay M, Trendelenburg M. Primary cytomegalovirus infection with accompanying Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia in a patient with large-vessel vasculitis. Infection. 2010;38:331-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Snape SE, Venkatesan P. Valganciclovir treatment of primary cytomegalovirus pneumonitis in an immunocompetent adult. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Karakelides H, Aubry MC, Ryu JH. Cytomegalovirus pneumonia mimicking lung cancer in an immunocompetent host. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:488-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Shimada A, Koga T, Shimada M, Kitajima T, Mitsui T, Sata M, Aizawa H. Cytomegalovirus pneumonitis presenting small nodular opacities. Intern Med. 2004;43:1198-1200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Simsir A, Oldach D, Forest G, Henry M. Rhodococcus equi and cytomegalovirus pneumonia in a renal transplant patient: diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Diagn Cytopathol. 2001;24:129-131. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 52. | Abbey A, Elsmore AC. Shortness of breath in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Belin V, Tebib J, Vignon E. Cytomegalovirus infection in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2003;70:303-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Kaşifoğlu T, Korkmaz C, Ozkan R. Cytomegalovirus-induced interstitial pneumonitis in a patient with dermatomyositis. Clin Rheumatol. 2006;25:731-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Chen Y, Tang Y, Zhang C, Lin R, Liu T, Shang S. Severe primary cytomegalovirus pneumonia in a 5-year-old immunocompetent child. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Tambe A, Gentile T, Ramadas P, Tambe V, Badrinath M. Cytomegalovirus Pneumonia Causing Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome After Brentuximab Vedotin Therapy. Am J Ther. 2019;26:e794-e795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Boussouar S, Campedel L, Noble PD, Turki MW, Calvo J, Pourcher V, Rolland-Debord C. Atypical presentation of CMV pneumonia in a heart transplant patient. Med Mal Infect. 2018;48:151-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Haddad JD, John JF Jr, Pappas AA. Cytomegalovirus pneumonia in sickle cell disease. Chest. 1984;86:265-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Katagiri A, Ando T, Kon T, Yamada M, Iida N, Takasaki Y. Cavitary lung lesion in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus: an unusual manifestation of cytomegalovirus pneumonitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2008;18:285-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Ayyappan AP, Thomas R, Kurian S, Christopher DJ, Cherian R. Multiple cavitating masses in an immunocompromised host with rheumatoid arthritis-related interstitial lung disease: an unusual expression of cytomegalovirus pneumonitis. Br J Radiol. 2006;79:e174-e176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Manian FA, Smith T. Ganciclovir for the treatment of cytomegalovirus pneumonia in an immunocompetent host. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:137-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | McCormack JG, Bowler SD, Donnelly JE, Steadman C. Successful treatment of severe cytomegalovirus infection with ganciclovir in an immunocompetent host. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1007-1008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Najjar M, Siddiqui AK, Rossoff L, Cohen RI. Cavitary lung masses in SLE patients: an unusual manifestation of CMV infection. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:182-184. [PubMed] |

| 64. | Taherifard E, Movahed H, Kiani Salmi S, Taherifard A, Abdollahifard S, Taherifard E. Cytomegalovirus coinfection in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection: a systematic review of reported cases. Infect Dis (Lond). 2022;54:543-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |