Published online Aug 28, 2022. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v10.i4.206

Peer-review started: March 27, 2022

First decision: June 11, 2022

Revised: July 27, 2022

Article in press: July 27, 2022

Published online: August 28, 2022

Processing time: 143 Days and 5.5 Hours

For decades and before the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, for health care workers (HCWs) burnout can be experienced as an upsetting confrontation with their self and the result of a complex a multifactorial process interacting with environmental and personal features.

To literature review and meta-analysis was to obtain a comprehensive und

We performed a database search of Embase, Google Scholar and PubMed from June to October 2020. We analysed burnout risk factors and protective factors in included studies published in peer-reviewed journals as of January 2020, studying a HCW population during the first COVID-19 wave without any geographic restrictions. Furthermore, we performed a meta-analysis to determine overall burnout levels. We studied the main risk factors and protective factors related to burnout and stress at the individual, institutional and regional levels.

Forty-one studies were included in our final review sample. Most were cross-sectional, observational studies with data collection windows during the first wave of the COVID-19 surge. Of those forty-one, twelve studies were included in the meta-analysis. Of the 27907 health care professionals who participated in the reviewed studies, 70.4% were women, and two-thirds were either married or living together. The most represented age category was 31-45 years, at 41.5%. Approximately half of the sample comprised nurses (47.6%), and 44.4% were working in COVID-19 wards (intensive care unit, emergency room and dedicated internal medicine wards). Indeed, exposure to the virus was not a leading factor for burnout. Our meta-analytic estimate of burnout prevalence in the HCW population for a sample of 6784 individuals was 30.05%.

There was a significant prevalence of burnout in HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic, and some of the associated risk factors could be targeted for intervention, both at the individual and organizational levels. Nevertheless, COVID-19 exposure was not a leading factor for burnout, as burnout levels were not notably higher than pre-COVID-19 levels.

Core Tip: We performed a database search from June to October 2020. We analysed burnout risk factors and protective factors in retained studies and performed a meta-analysis to determine overall burnout levels during the initial coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak. We found a significant preva

- Citation: Kimpe V, Sabe M, Sentissi O. No increase in burnout in health care workers during the initial COVID-19 outbreak: Systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Meta-Anal 2022; 10(4): 206-219

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v10/i4/206.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v10.i4.206

Burnout is an occupational phenomenon defined as a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization of others, and a feeling of reduced personal accomplishment[1,2]. It is the result of a complex and multifactorial process, with interacting environmental features and personal frailties[3-6], in a process that juxtaposes personal needs and expectations on one hand, and the institution’s demands, (in)equalities and (in)justices on the other. For health care workers (HCWs), burnout can be experienced as an upsetting personal confrontation, as the progressive lack of compassion and diminished effectiveness has a distressing impact on their professional identity[4]. The scientific literature on HCW burnout is vast, as decades before the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, burnout was recognized as a significant problem both in terms of magnitude and impact. A recent systematic review over a period of 25 years showed burnout levels of 25% among nurses[7]. Another recent meta-analysis studying physicians reported a combined prevalence of 21%, although with substantial variability due to uneven definitions, assessment methods, and study quality[8]. In the past decade, an increasing number of respiratory virus epidemics have placed additional pressure on the health care system and its workers through various mechanisms. During the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak, some HCWs isolated themselves out of fear of infecting their friends and families[9], and lack of training, protection and hospital support was associated with higher burnout[10]. The novel influenza A virus (H1N1) outbreak in 2009 highlighted HCWs’ concern for infection of family and friends and fears about consequences for their own health[11]. Other authors showed an increase in the stress and psychological burden of HCWs during the 2012 Middle East Respiratory Syndrome outbreak, due to infectious disease-related stigma, such as social rejection or discrimination[12], or increased burnout levels due to poor hospital resources[13].

Early 2020, economic uncertainty and societal anxiety reached unseen levels, as the COVID-19 pandemic profoundly changed our view of health, work and social interactions. As the UN put it, we are facing a global health crisis […], one that is killing people, spreading human suffering, and upending people’s lives. However, this is much more than a health crisis. It is a human, economic and social crisis[14]. For most workers, the pandemic has accelerated a change in workplace habits and a shift from office work towards teleworking. HCWs, however, were subject to sudden and dramatic transformation of the health care institutions and were faced with unseen numbers of critically ill patients and casualties. In many countries, the pandemic was source of a tremendous increase in workload and significant levels of stress and fear regarding physical integrity. Most countries were faced with an ominous atmosphere of fear of the unknown and a staggering shortage of means, including personal protective equipment (PPE). Particularly in the early days of the pandemic, HCWs were facing uncertainty about the virus’s modes of transmission, questions about levels of contagiousness, and hence about the risk of self-infection and of infecting family members and friends.

Burnout in HCWs has been associated with poor patient safety outcomes, medical errors and adverse outcomes on the health care system as a whole[15,16]. In this review, we explore the main contributors to burnout in health care providers, specifically within the scope of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. Despite the great variability in burnout measuring instruments, subscales, and cut-off levels therein, we endeavour to provide a meta-analytic estimate of burnout levels during the initial COVID-19 outbreak.

We conducted a literature search in PubMed, Embase and Google Scholar from 1st of June to 10th of October 2020, following the PRISMA 2020 recommendations (unregistered). The search terms were associated with Boolean operators as detailed in Supplementary Table 1. Some additional relevant articles were included from the references sections of the articles found in the initial search.

We included original studies published in peer-reviewed journals as of January 2020, studying an HCW population during the first COVID-19 wave without any geographic restrictions. The exclusion criteria are detailed in Table 1. Initially, assessed studies comprised several randomized controlled trials (RCTs), mostly cross-sectional and some interventional studies. From those, RCTs and interventional studies were excluded during the screening phase, as they were not within the burnout or stress scope of this review.

| Studies that did not unambiguously study burnout and/or stress at work |

| Studies that did not focus on HCWs or a subpopulation thereof |

| Literature reviews, meta-analyses and systematic reviews |

| Full English text not available |

| Preprints, unreviewed articles |

| Short communications, editorials, etc. (not sufficient data) |

The main independent variable was burnout and its prevalence during the COVID-19 pandemic in the first half of 2020 as measured with a recognized instrument or validated custom instrument. High levels of chronic work-related stress are generally accepted as a precipitator of burnout, and a recent study showed that high stress levels interfere with sound sleep[17], which in turn can precipitate burnout. Taking this into consideration, we included (perceived) stress as an independent variable in our analysis.

The main instrument used is the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), a scale measuring burnout through three dimensions: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP) and decreased personal achievement (PA)[18,19]. EE refers to feelings of being overextended and depletion of one’s resources[6]. Conceptually, it incorporates traditional stress reactions, such as job-related depression, psychosomatic complaints and anxiety[20,21], and has been related to similar behavioural outcomes, such as intention to quit and absenteeism[22]. HCWs experiencing EE feel apathetic and indifferent about their work and patients and no feel longer invested in situations arising during their workday[23]. DP refers to a cynical, insensitive, or disproportionately detached response to other people as EE becomes more severe. It can be perceived as withdrawal or mental distancing from care recipients[24], which are distancing techniques used to reduce the intensity of arousal and prevent the worker from disruption in critical and chaotic situations requiring calm and efficient functioning[25]. PA refers to a decline in one’s feelings of competence and successful achievement at work, reduced productivity, low morale and inability to cope[26]. One can appreciate how reduced performance and productivity among HCWs lead to poor clinical decision-making and medical errors[23]. The questions used in the MBI are detailed in Supplementary Table 2. Other instruments used are detailed in Supplementary Table 3.

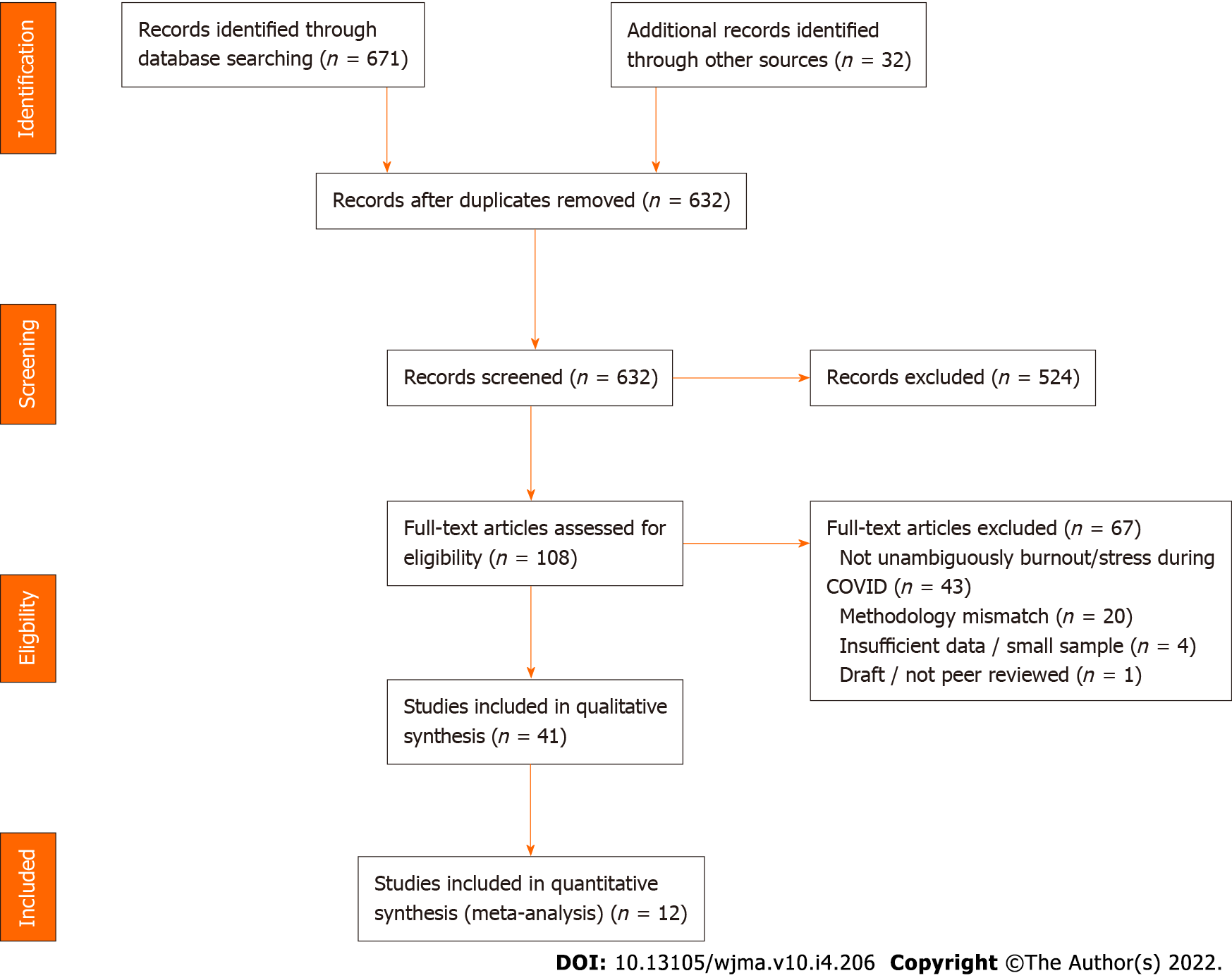

The dependent variables were sociodemographic variables, personality traits, psychological and physical health status, occupational role, ward, organizational and geographic variables. Physical symptoms were described in certain studies, but they were not the focus of this review. The detailed study selection process is outlined in the flow chart in Figure 1.

Units were unified for aggregation of dependent variables. When only median age and standard deviation were available, we used normal distribution inference to categorize the respondents into age categories. For other studies, we forced study age groups in the closest comparable group of our review. These adaptations may report inaccurate age distributions at the individual study level, but we believe that the aggregated data benefit from this approach. Meta-analysis was performed in MedCalc Version 19.5.3. Proportions with random effects models were studied, and we calculated the

From the final list of retained studies, we selected those that had sufficient numeric data to perform a meta-analysis. These studies used validated burnout measuring instruments and reported either burnout prevalence or scores that permitted deducing HCW burnout prevalence. Descriptive analysis was performed using statistically significant data from the studies retained. For some studies, the conclusions retained in our review may not have been the most striking outcomes from their perspective. We focused mainly on burnout, stress, and related dependent variables.

Through screening, 39 cross-sectional, one longitudinal and one prospective cohort study were retained. Of the 41 studies, all from 2020, 12 were included in the meta-analysis. Table 2 details the main features of the studies.

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Publication month (2020) | Region | ||||

| March | 1 | 2 | Asia & Pacific | 12 | 29 |

| April | 3 | 7 | Europe | 18 | 44 |

| May | 3 | 7 | Global | 2 | 5 |

| June | 5 | 12 | Middle east | 3 | 7 |

| July | 3 | 7 | North America | 4 | 10 |

| August | 15 | 37 | South/Latin America | 2 | 5 |

| September | 6 | 15 | |||

| October | 5 | 12 | Population | ||

| Physicians | 36 | 88 | |||

| Type of work | Nurses | 27 | 66 | ||

| Cross-sectional survey | 39 | 95 | Other HCWs | 17 | 41 |

| Longitudinal study | 1 | 2 | |||

| Longitudinal cohort study | 1 | 2 | Measuring scale | ||

| Validated burnout scale | 18 | 44 | |||

| Validated stress scale | 18 | 44 |

Of the studies retained, 44% were European studies, and 28% studied Asian-Pacific countries. After China, the pandemic hit hardest in European countries, such as Italy and Spain, in the first quarter of 2020. These two countries represented 21% and 19% of the respondents of European studies, respectively. Among the latter, Germany represented 39%. Table 3 shows a sociodemographic overview of respondents in the 41 studies. Of the 27907 health care professionals who participated in the reviewed studies, 70.4% were women, and two-thirds were either married or living together. The most represented age category was 31-45 years, at 41.5%. Approximately half of the sample comprised nurses (47.6%), and 44.4% were working in COVID-19 wards [intensive care unit (ICU), emergency room (ER) and dedicated internal medicine wards]. Supplementary Table 4 displays the complete list of studies and, for each study, a short description summarizing the main conclusions relevant for our review.

| N | % | |||||||

| Region | Asia & Pacific | Europe | Middle east | North America | South/Latin America | Multi-country | Total | |

| Studies | 12 | 18 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 41 | |

| Respondents | 12587 | 9754 | 1774 | 1546 | 512 | 1734 | 27907 | |

| % | 45.1 | 35.0 | 6.4 | 5.5 | 1.8 | 6.2 | ||

| Gendera | ||||||||

| Female | 9775 | 6590 | 1176 | 544 | 179 | 342 | 18606 | 70.4 |

| Male | 2695 | 3'073 | 598 | 339 | 333 | 659 | 7697 | 29.1 |

| Non-binary/other | 37 | 91 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 129 | 0.5 |

| Age categoryb | ||||||||

| 18-30 | 5344 | 1767 | 430 | 407 | 94 | 397 | 8439 | 30.7 |

| 31-45 | 5134 | 3543 | 1157 | 676 | 249 | 639 | 11398 | 41.5 |

| > 45 | 2078 | 4019 | 187 | 460 | 169 | 699 | 7612 | 27.7 |

| Occupational role | ||||||||

| Physician | 3308 | 3780 | 799 | 1134 | 512 | 1734 | 11267 | 40.4 |

| Nurse | 7996 | 4499 | 552 | 248 | 0 | 0 | 13295 | 47.6 |

| Other | 1283 | 1475 | 423 | 164 | 0 | 0 | 3345 | 12.0 |

| Warda | ||||||||

| Front line | 5336 | 2931 | 860 | 947 | 0 | 1001 | 11075 | 44.4 |

| Usual ward | 7251 | 4212 | 914 | 252 | 512 | 733 | 13874 | 55.6 |

| Married/concubinea | ||||||||

| Yes | 5704 | 2624 | 987 | 92 | - | 831 | 10238 | 66.2 |

| No | 3691 | 1204 | 149 | 19 | - | 170 | 5233 | 33.8 |

| Childrena | ||||||||

| Yes | 515 | 1086 | 277 | 185 | - | 0 | 2063 | 48.6 |

| No | 905 | 778 | 149 | 352 | - | 0 | 2184 | 51.4 |

| Psychological comorbiditiesa | ||||||||

| Yes | - | 45 | 122 | - | 18 | 0 | 185 | 9.2 |

| No | - | 675 | 1013 | - | 145 | 0 | 1833 | 90.8 |

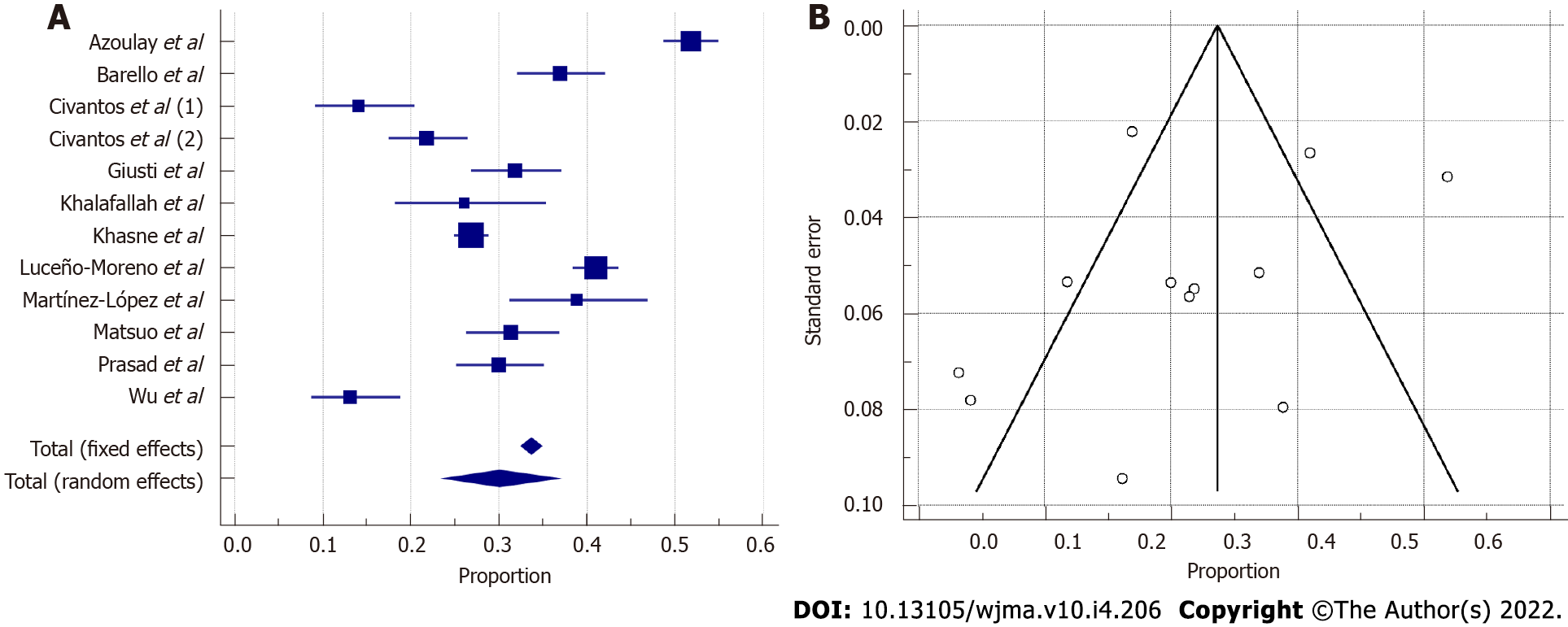

Twelve studies were included in our meta-analysis (Figure 2). Egger’s test result was -3.7859 (95%CI:

The typical profile of an HCW with high levels of burnout was a single female nurse or resident physician under 30 years of age in an institution perceived as poorly prepared for the COVID-19 pandemic. This HCW experienced anxiety regarding infection with COVID-19 or infecting their friends and family and might have had a history of prior psychiatric conditions and low levels of resilience.

A recurring risk factor associated with burnout was female sex[27-34]. Female sex was correlated with higher perceived stress[17,35-38], despite one study showing identical cortisol levels as in males. This is consistent with males being less likely to report symptoms, even if they were experiencing them[29,30], and with females having a higher tendency to somatise[34].

Early residency years and younger age were associated with higher stress levels, burnout and associated negative symptoms[17,29-31,35,40-42]. Younger physicians are more likely to have young children, which may explain the increased stress of infecting families. Accordingly, one study found higher perceived stress levels in HCWs with small children[43]. In nurses, the number of children and parenting stress were positively correlated with burnout[44]. Some authors stated that senior residents experienced more stress because of the inability to quickly adapt to a new subject they never learned in medical school[45]. Among nonphysicians, younger HCWs had lower levels of burnout than middle-aged groups[46], although other authors found that more experience comes with less burnout[47].

Single respondents experienced higher burnout than those who were married or in a relationship[36,44]. Respondents with support from family and friends scored lower on stress and burnout[34-36,48], whereas living alone predicted increased stress[49]. We believe that social support could be considered an external resource that alleviates burnout, fitting the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) burnout model[24].

Prior psychiatric conditions were strongly correlated with high levels of burnout and distress[29,48]. Higher levels on the EE and DP subscales were linked with more negative symptoms[28,42], including irritability, change in food habits, insomnia, depression and muscle tension[50]. Similarly, reporting physical symptoms was associated with higher stress levels[51], although this association may be bidirectional[52]. Additionally, an association was found between EE and the perception of needing psychiatric treatment in the future[53].

A positive attitude was strongly protective against stress, whereas avoidance constituted a risk factor[36,49]. Stigma (discrimination, fear of COVID-19) was an important predictor of burnout[33]. Resilience was associated with lower levels of stress, anxiety, fatigue, and sleep disturbances[54], as well as less COVID-19-related anxiety[55], symptoms of posttraumatic stress and depression[42] and burnout[44]. Resilience is a complex coping mechanism in which individuals can function in difficult environments. Focusing on solutions rather than on difficulties puts the individual in a position that favours the development of new skills[56,57].

Several authors reported higher levels of stress or burnout in nurses than in physicians or other HCWs[38,41,43,46,51,58]. Several authors who studied the nurse population highlighted the importance of organizational support, safety guidelines, and PPE as protective from burnout related to anxiety about self-infection or infection of friends and families[32,34,55,59]. Some authors found that nurses had high morale, enthusiasm and empathy, which could partially set off burnout along the DP axis[47]. Despite having similar stress levels to physicians and working in equally difficult situations in terms of the availability of resources, nurses scored higher compassion satisfaction (CS), which protects against burnout[60].

There is an important intersection between nurses and the female population; women accounted for 93.2% among four studies studying only nurses, making female sex an important confounding factor. In many cultures, women are still in charge of the household and the children, often causing a surplus in workload and obligations. The nursing population had to deal with increased workload at work and locked-down children who needed to be fed and protected from infection. Additionally, nurses spending the most time with patients are most vulnerable to the risk of infection if PPE is lacking.

Interestingly, a few studies found that whether HCWs dealt directly with COVID-19 patients did not correlate with burnout or stress[51,61], possibly because it was counterbalanced by higher CS[62]. For others, the actual duration of interactions with COVID patients was associated with a higher risk of burnout[17,48,61]. In ICUs around the world, direct COVID-19 exposure was not a leading factor for burnout[27]. Some authors found that working with COVID-19 patients increased stress[31,36-38,54,63,64]. Others found the opposite: lower burnout levels in front-line wards (FL) compared to usual wards (UW)[65,66]. The number of positive cases in the country was not associated with burnout or stress[46,67]. Some authors stated that redeployed staff had a higher risk of burnout, possibly related to increased demands, limited resources, and psychological stress of dealing with an unfamiliar disease in an unfamiliar environment[40]. Others found that redeployment had no impact on perceived stress[59]. One study found that surgical residents had a decrease in routine surgical activities along with a decrease in burnout[68].

The predominant theory appears to be that FL workers were subject to less burnout than UW workers. We postulate that FL had more opportunity to exercise competencies and judgement, thereby increasing their sense of control. From the Job Strain-Job Decision model perspective, this put these workers in active jobs, with higher job satisfaction and actual development of competencies, setting off part of the higher stress (vs UW) and generating new behaviour patterns[69]. Accordingly, Dinibutun[70] found a high sense of PA among physicians in FL. We also suggest that FL workers experienced increased attention from hospital management, with more communication and updated policies. FL workers received public and media recognition, increasing their sense of worth, experienced by some as justice, at last. Several burnout models appreciate that recognition and sense of worth act as enhancers of rewards, alleviating high efforts[71,72] as somehow protective from burnout.

In primary care, some authors measured lower levels of psychological distress, possibly explained by the use of telemedicine, alleviating the risk of infection[73]. We believe, however, that unprepared implementation of technological diagnostic tools can also lead to technostress. This is suitably illustrated by a global study amongst dermatologists who started using telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic[50].

Higher actual or perceived preparedness at the hospital or country level was associated with lower stress or burnout[27,43,50,53,58,59]. Underlying features of preparedness included availability of PPE, training, communication, and protocols; improving these could alleviate perceived stress[58,74,75]. Increased stress and burnout related to preparedness was partially mediated by fear of self-infection and infection of others[32,48,50,52,59]. Increased appreciation and communication from hospital management was correlated with less burnout[74], whereas institutional failure to triage appropriately, or a lack of ethical climate increased stress and burnout[27]. Having been tested for COVID-19 or sufficient and discretionary access to testing for patients seemed protective from burnout[74]. Con

Preparedness is a textbook illustration of burnout models in action. The unavailability of resources (such as PPE) to accomplish one’s job in the best possible conditions increases disengagement and DP, as postulated in the JD-R model[24,53], increases strain through anxiety of transmitting the virus[69] and decreases resources through social isolation (to avoid transmission)[24]. Lack of institutional communication and protocols are decreased reward components in the Effort-Reward Imbalance model: they create job and institutional uncertainty[71] and might be perceived as unjust by the worker[72].

According to several pre-COVID-19 meta-analyses, burnout prevalence among residents was 35.7%[76] or above 60%[77]. Among nurses, burnout prevalence was between 15% and 28%[78], between 29% and 36%[79] and between 15% and 35%[80]. The pooled prevalence of a 2020 meta-analysis among 1943 emergency physicians was between 35% and 41%[81]. Our own meta-analytic estimate of burnout during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic was approximately 30%, i.e., less than most studies pre-COVID-19. We hypothesize that, although HCWs were put under enormous strain during this period, they were also rewarded by a considerable increase in attention and had the opportunity to give actual sense to their profession, albeit in very difficult circumstances. Additionally, we must put this number in perspective, as it is based on very different studies in terms of duration, methodology and geography.

The short time span of a pandemic does not necessarily allow for the time and preparation needed to set up a well-structured randomized controlled trial. This may explain the lack of many such studies and their subsequent absence in our review. Cross-sectional studies, in contrast, do not admit explanation by causality. The absence of a control group in cross-sectional studies does not allow us to determine if findings are reflective of the general population or only of considered HCWs.

Responder bias and auto-questionnaires are important limitations of cross-sectional studies. Certain topics, such as a prior history of psychiatric conditions, are particularly at risk of response bias given the possible stigma. Additionally, at the time of the survey, HCWs might not have been interested due to a lack of any personal (mental) health concerns, or conversely, they could have been suffering from a crushing burden of either stress, burnout, or physical symptoms, preventing them from responding to the survey.

Another limitation of this review is that, during this pandemic, we must consider that occupational burnout could have been caused by the interaction between environmental-related (such as workplace-related events) and individual-related factors (such as disruption of work–life balance and personality traits)[81].

Limitations specific to our review and meta-analysis are the heterogeneity of studies in terms of measurement instruments, scales and subscales, and cut-off scores used to determine overall burnout prevalence. There was also geographic diversity and heterogeneity of the populations studied, as our intention was not to focus on one part of the workforce or region but to highlight burnout and its influencing factors in the specific context of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, we cannot compare the prevalence of our study with the prevalence found in earlier, pre-COVID-19 studies.

It is critical that countries and institutions understand and acknowledge the nature, risk factors and protective factors of stress and burnout in their health care workforce. Awareness lies at the basis of preventive interventions, which can happen both at the individual and institutional levels.

In a pandemic context such as COVID-19, specific interventions could probably yield immediate results, benefiting HCWs and patients in very direct ways. We have highlighted how institutional preparedness has a clear correlation with stress and burnout. PPE, up to date protocols, and regular communication from hospital management are low hanging fruit, as they would both reduce actual infection rates amongst staff and alleviate fear of infection and transmission. Workload and stress about childcare are recurring subjects, and if the former is a challenge during a pandemic, it should be feasible for institutions to help organise childcare for single workers who are more at risk for burnout.

Commonly studied burnout interventions in HCWs are mindfulness, stress management and small-group discussions. The results suggest that these factors could have positive effects on burnout, although more research is needed[82]. A recent mapping by Hilton et al[83] of RCTs conducted in health care providers and medical students returned promising results on the use of mindfulness in the workplace but highlighted the need for more definitive evidence of benefits on burnout. Other interventions focus on leadership skills, community and institutional culture, which have been largely studied[84,85].

Where prevention fails, institutions must deal with existing stress and burnout resulting from both ordinary and extraordinary circumstances. Some institutions implemented telephone helplines for HCWs with difficulties coping with grief, death, high workloads, and burnout, the use of which was perceived as useful and appropriate[86,87]. A culture promoting acknowledgement, communication and peer support programs, employee assistance programs and structured health response programs are many other exploration options.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, HCWs have been under high levels of stress and have suffered considerable burnout, putting quality of care at risk. We reviewed 41 studies and highlighted personal and sociodemographic features strongly associated with higher perceived stress and burnout. Female sex, younger age, low resilience, nurse occupational role and lack of preparedness were associated with higher burnout, but actual COVID-19 exposure was not a leading factor. Prevalence pre-COVID-19 was either lower or in the same ballpark as during COVID-19; our meta-analytic estimate based on 12 studies and approximately 6800 respondents returned a burnout prevalence of 30%, with important geographical variations. Both the individual and macro levels offer opportunities for intervention, as primary and secondary prevention, but the identification of early signs could also inform a reduction in burnout levels in our health care workforce. Further research is needed to evaluate the mid- and long-term impacts of the COVID-19 outbreak on HCWs.

For decades and before the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, for health care workers, (HCWs) burnout can be experienced as an upsetting confrontation with their self and the result of a complex a multifactorial process interacting with environmental and personal features.

During these century previous outbreak, some HCWs isolated themselves out of fear of infecting their friends and families, and lack of training, protection and hospital support was associated with higher burnout.

The objective of this literature review and meta-analysis was to obtain a comprehensive understanding of burnout and work-related stress in health care workers around the world during the first outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

We analysed burnout risk factors and protective factors in included studies published from June 1, 2020 to October 10, 2020, studying an HCW population during the first COVID-19 wave. The typical profile of an HCW with high levels of burnout was a young, single, female nurse or resident physician in an institution perceived as poorly prepared for the COVID-19 pandemic. This HCW experienced anxiety related to infection with COVID-19 or infecting her friends and family and possibly had a history of prior psychiatric conditions and low levels of resilience. Nevertheless, COVID-19 exposure was not a leading factor in burnout, as burnout levels were not notably higher than those before the COVID-19 pandemic. We included original studies published in peer-reviewed journals as of January 2020, studying an HCW population during the first COVID-19 wave without any geographic restrictions

Through screening, 39 cross-sectional, one longitudinal and one prospective cohort study were retained. Of the 41 studies, all from 2020, 12 were included in the meta-analysis. Table 2 details the main features of the studies. Of the 27907 health care professionals who participated in the reviewed studies, 70.4% were women, and two-thirds were either married or living together. The most represented age category was 31-45 years, at 41.5%. Approximately half of the sample comprised nurses (47.6%), and 44.4% were working in COVID-19 wards (intensive care unit, emergency room and dedicated internal medicine wards). The meta-analytic estimate of burnout prevalence in HCWs was 30.05% (95%CI: 23.91%–36.5%), with a sample size of 6784.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, HCWs have been under high levels of stress and have suffered considerable burnout, putting quality of care at risk. We reviewed 41 studies and highlighted personal and sociodemographic features strongly associated with higher perceived stress and burnout. Female sex, younger age, low resilience, nurse occupational role and lack of preparedness were associated with higher burnout, but actual COVID-19 exposure was not a leading factor. Prevalence pre-COVID-19 was either lower or in the same ballpark as during COVID-19; our meta-analytic estimate based on 12 studies and approximately 6800 respondents returned a burnout prevalence of 30%, with important geographical variation

In a pandemic context such as COVID-19, specific interventions could probably yield immediate results, benefiting HCWs and patients in very direct ways. We have highlighted how institutional preparedness has a clear correlation with stress and burnout. PPE, up-to-date protocols and regular communication from hospital management are low hanging fruit, as they would both reduce actual infection rates amongst staff and alleviate fear of infection and transmission. Workload and stress about childcare are recurring subjects, and if the former is a challenge during a pandemic, it should be feasible for ins

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: Switzerland

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Eseadi C, Nigeria; Khosravi M, Iran S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | World Health Organization. Burn-Out an "Occupational Phenomenon": International Classification of Diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019 . [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Maslach C. Burnout the Cost of Caring. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1982. |

| 3. | Pines AM, Aronson E, Kafry D. Burnout: From Tedium to Personal Growth. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1981. |

| 5. | Freudenberger HJ, Richelson G. Bum-Out: The High Cost of High Achievement. New York, NY: Anchor Press; 1980. |

| 6. | Burisch M, Schaufeli WB, Maslach C, Marek T. Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis; 1993. |

| 7. | Adriaenssens J, De Gucht V, Maes S. Determinants and prevalence of burnout in emergency nurses: a systematic review of 25 years of research. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:649-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 364] [Cited by in RCA: 427] [Article Influence: 42.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, Rosales RC, Guille C, Sen S, Mata DA. Prevalence of Burnout Among Physicians: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2018;320:1131-1150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 950] [Cited by in RCA: 1116] [Article Influence: 159.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bai Y, Lin CC, Lin CY, Chen JY, Chue CM, Chou P. Survey of stress reactions among health care workers involved with the SARS outbreak. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:1055-1057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 655] [Cited by in RCA: 625] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Balderson KE, Bennett JP, Borgundvaag B, Evans S, Fernandes CM, Goldbloom DS, Gupta M, Hunter JJ, McGillis Hall L, Nagle LM, Pain C, Peczeniuk SS, Raymond G, Read N, Rourke SB, Steinberg RJ, Stewart TE, VanDeVelde-Coke S, Veldhorst GG, Wasylenki DA. Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1924-1932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 863] [Cited by in RCA: 735] [Article Influence: 38.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Goulia P, Mantas C, Dimitroula D, Mantis D, Hyphantis T. General hospital staff worries, perceived sufficiency of information and associated psychological distress during the A/H1N1 influenza pandemic. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Park JS, Lee EH, Park NR, Choi YH. Mental Health of Nurses Working at a Government-designated Hospital During a MERS-CoV Outbreak: A Cross-sectional Study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2018;32:2-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim JS, Choi JS. Factors Influencing Emergency Nurses' Burnout During an Outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus in Korea. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2016;10:295-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Everyone Included: Social Impact of COVID-19. New York, NY: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs; 2020. |

| 15. | Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, Tsipa A, O'Connor DB. Healthcare Staff Wellbeing, Burnout, and Patient Safety: A Systematic Review. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1102] [Cited by in RCA: 936] [Article Influence: 104.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Patel RS, Bachu R, Adikey A, Malik M, Shah M. Factors Related to Physician Burnout and Its Consequences: A Review. Behav Sci (Basel). 2018;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 435] [Article Influence: 62.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Abdulah DM, Mohammed AA. The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on perceived stress in clinical practice: experience of doctors in Iraqi Kurdistan. Rom J Intern Med. 2020;58:219-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2:99-113. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Maslach C, Leiter MP, Schaufeli W. Measuring burnout. In: Cooper CL, Cartwright S, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Well Being. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2008; 86-108. |

| 20. | Buunk B, De Jonge J, Ybema J. Work psychology. In: Drenth PJD, Thierry H, De Wolff CJ, editors. Handbook of Work and Organizational Psychology. Hove: Psychology Press, 1998; 145-82. |

| 21. | Kahn RL, Byosiere P. Stress in organizations. In: Dunnette MD, Hough LM, editors. Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1992. p. 571-650. |

| 22. | Lee RT, Ashforth BE. A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. J Appl Psychol. 1996;81:123-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1647] [Cited by in RCA: 1040] [Article Influence: 35.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bridgeman PJ, Bridgeman MB, Barone J. Burnout syndrome among healthcare professionals. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75:147-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86:499-512. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | Maslach C. Burnout: a multidimensional perspective. In: Schaufeli WB, Maslach C, Marek T, editors. Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis, 1993; 19-32. |

| 26. | Maslach C. Understanding burnout: definitional issues in analyzing a complex phenomenon. In: Paine WS, editor. Job Stress and Burnout. Beverly Hills: Sage, 1982; 29-40. |

| 27. | Azoulay E, De Waele J, Ferrer R, Staudinger T, Borkowska M, Povoa P, Iliopoulou K, Artigas A, Schaller SJ, Hari MS, Pellegrini M, Darmon M, Kesecioglu J, Cecconi M; ESICM. Symptoms of burnout in intensive care unit specialists facing the COVID-19 outbreak. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10:110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 43.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Barello S, Palamenghi L, Graffigna G. Burnout and somatic symptoms among frontline healthcare professionals at the peak of the Italian COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 396] [Cited by in RCA: 375] [Article Influence: 75.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Civantos AM, Bertelli A, Gonçalves A, Getzen E, Chang C, Long Q, Rajasekaran K. Mental health among head and neck surgeons in Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national study. Am J Otolaryngol. 2020;41:102694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Civantos AM, Byrnes Y, Chang C, Prasad A, Chorath K, Poonia SK, Jenks CM, Bur AM, Thakkar P, Graboyes EM, Seth R, Trosman S, Wong A, Laitman BM, Harris BN, Shah J, Stubbs V, Choby G, Long Q, Rassekh CH, Thaler E, Rajasekaran K. Mental health among otolaryngology resident and attending physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic: National study. Head Neck. 2020;42:1597-1609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Elbay RY, Kurtulmuş A, Arpacıoğlu S, Karadere E. Depression, anxiety, stress levels of physicians and associated factors in Covid-19 pandemics. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 377] [Cited by in RCA: 403] [Article Influence: 80.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Khasne RW, Dhakulkar BS, Mahajan HC, Kulkarni AP. Burnout among Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic in India: Results of a Questionnaire-based Survey. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020;24:664-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ramaci T, Barattucci M, Ledda C, Rapisarda V. Social Stigma during COVID-19 and its impact on HCWs outcomes. Sustainability. 2020; 12: 3834. |

| 34. | Hong S, Ai M, Xu X, Wang W, Chen J, Zhang Q, Wang L, Kuang L. Immediate psychological impact on nurses working at 42 government-designated hospitals during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A cross-sectional study. Nurs Outlook. 2021;69:6-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Arafa A, Mohammed Z, Mahmoud O, Elshazley M, Ewis A. Depressed, anxious, and stressed: What have healthcare workers on the frontlines in Egypt and Saudi Arabia experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic? J Affect Disord. 2021;278:365-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Babore A, Lombardi L, Viceconti ML, Pignataro S, Marino V, Crudele M, Candelori C, Bramanti SM, Trumello C. Psychological effects of the COVID-2019 pandemic: Perceived stress and coping strategies among healthcare professionals. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 42.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Kannampallil TG, Goss CW, Evanoff BA, Strickland JR, McAlister RP, Duncan J. Exposure to COVID-19 patients increases physician trainee stress and burnout. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0237301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 46.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, Wu J, Du H, Chen T, Li R, Tan H, Kang L, Yao L, Huang M, Wang H, Wang G, Liu Z, Hu S. Factors Associated With Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e203976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5313] [Cited by in RCA: 4372] [Article Influence: 874.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Çalık M, Uzun N, Aksoy N. The unit-based stress and anxiety correlation of healthcare workers during the COVID 19 outbreak. J Allergy Infect Dis. 2020;1:25-31. |

| 40. | Khalafallah AM, Lam S, Gami A, Dornbos DL, Sivakumar W, Johnson JN, Mukherjee D. A national survey on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic upon burnout and career satisfaction among neurosurgery residents. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;80:137-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Matsuo T, Kobayashi D, Taki F, Sakamoto F, Uehara Y, Mori N, Fukui T. Prevalence of Health Care Worker Burnout During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic in Japan. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2017271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 43.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Luceño-Moreno L, Talavera-Velasco B, García-Albuerne Y, Martín-García J. Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress, Anxiety, Depression, Levels of Resilience and Burnout in Spanish Health Personnel during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 391] [Cited by in RCA: 337] [Article Influence: 67.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kuo FL, Yang PH, Hsu HT, Su CY, Chen CH, Yeh IJ, Wu YH, Chen LC. Survey on perceived work stress and its influencing factors among hospital staff during the COVID-19 pandemic in Taiwan. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2020;36:944-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Bashirian S, Bijani M, Borzou SR, Khazaei S. Resilience, Occupational Burnout, and Parenting Stress in Nurses Caring for COVID-2019 Patients. 2020. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 45. | Abdessater M, Rouprêt M, Misrai V, Matillon X, Gondran-Tellier B, Freton L, Vallée M, Dominique I, Felber M, Khene ZE, Fortier E, Lannes F, Michiels C, Grevez T, Szabla N, Boustany J, Bardet F, Kaulanjan K, Seizilles de Mazancourt E, Ploussard G, Pinar U, Pradere B; Association Française des Urologues en Formation (AFUF). COVID19 pandemic impacts on anxiety of French urologist in training: Outcomes from a national survey. Prog Urol. 2020;30:448-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Prasad A, Civantos AM, Byrnes Y, Chorath K, Poonia S, Chang C, Graboyes EM, Bur AM, Thakkar P, Deng J, Seth R, Trosman S, Wong A, Laitman BM, Shah J, Stubbs V, Long Q, Choby G, Rassekh CH, Thaler ER, Rajasekaran K. Snapshot Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Wellness in Nonphysician Otolaryngology Health Care Workers: A National Study. OTO Open. 2020;4:2473974X20948835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Guixia L, Hui Z. A study on burnout of nurses in the period of COVID-19. Psychol Behav Sci. 2020;9:31-6. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Giusti EM, Pedroli E, D'Aniello GE, Stramba Badiale C, Pietrabissa G, Manna C, Stramba Badiale M, Riva G, Castelnuovo G, Molinari E. The Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Outbreak on Health Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 57.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 49. | Chew QH, Chia FL, Ng WK, Lee WCI, Tan PLL, Wong CS, Puah SH, Shelat VG, Seah ED, Huey CWT, Phua EJ, Sim K. Perceived Stress, Stigma, Traumatic Stress Levels and Coping Responses amongst Residents in Training across Multiple Specialties during COVID-19 Pandemic-A Longitudinal Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Bhargava S, Sarkar R, Kroumpouzos G. Mental distress in dermatologists during COVID-19 pandemic: Assessment and risk factors in a global, cross-sectional study. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e14161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Holton S, Wynter K, Trueman M, Bruce S, Sweeney S, Crowe S, Dabscheck A, Eleftheriou P, Booth S, Hitch D, Said CM, Haines KJ, Rasmussen B. Psychological well-being of Australian hospital clinical staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aust Health Rev. 2021;45:297-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Tan BYQ, Jing M, Goh Y, Ngiam NJH, Yeo LLL, Ahmad A, Ahmed Khan F, Napolean Shanmugam G, Sharma AK, Komalkumar RN, Meenakshi PV, Shah K, Patel B, Chan BPL, Sunny S, Chandra B, Ong JJY, Paliwal PR, Wong LYH, Sagayanathan R, Chen JT, Ying Ng AY, Teoh HL, Tsivgoulis G, Ho CS, Ho RC, Sharma VK. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:559-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1009] [Cited by in RCA: 996] [Article Influence: 199.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Martínez-López JÁ, Lázaro-Pérez C, Gómez-Galán J, Fernández-Martínez MDM. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Emergency on Health Professionals: Burnout Incidence at the Most Critical Period in Spain. J Clin Med. 2020;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Huffman EM, Athanasiadis DI, Anton NE, Haskett LA, Doster DL, Stefanidis D, Lee NK. How resilient is your team? Am J Surg. 2021;221:277-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Labrague LJ, De Los Santos JAA. COVID-19 anxiety among front-line nurses: Predictive role of organisational support, personal resilience and social support. J Nurs Manag. 2020;28:1653-1661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in RCA: 555] [Article Influence: 111.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Chen S, Bonanno GA. Psychological adjustment during the global outbreak of COVID-19: A resilience perspective. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12:S51-S54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 44.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Foster K, Roche M, Delgado C, Cuzzillo C, Giandinoto JA, Furness T. Resilience and mental health nursing: An integrative review of international literature. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2019;28:71-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Kramer V, Papazova I, Thoma A, Kunz M, Falkai P, Schneider-Axmann T, Hierundar A, Wagner E, Hasan A. Subjective burden and perspectives of German healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;271:271-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Sampaio F, Sequeira C, Teixeira L. Nurses' Mental Health During the Covid-19 Outbreak: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Occup Environ Med. 2020;62:783-787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Ruiz-Fernández MD, Ramos-Pichardo JD, Ibáñez-Masero O, Cabrera-Troya J, Carmona-Rega MI, Ortega-Galán ÁM. Compassion fatigue, burnout, compassion satisfaction and perceived stress in healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 health crisis in Spain. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29:4321-4330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 56.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Man MA, Toma C, Motoc NS, Necrelescu OL, Bondor CI, Chis AF, Lesan A, Pop CM, Todea DA, Dantes E, Puiu R, Rajnoveanu RM. Disease Perception and Coping with Emotional Distress During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Survey Among Medical Staff. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Buselli R, Corsi M, Baldanzi S, Chiumiento M, Del Lupo E, Dell'Oste V, Bertelloni CA, Massimetti G, Dell'Osso L, Cristaudo A, Carmassi C. Professional Quality of Life and Mental Health Outcomes among Health Care Workers Exposed to Sars-Cov-2 (Covid-19). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 43.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Alshekaili M, Hassan W, Al Said N, Al Sulaimani F, Jayapal SK, Al-Mawali A, Chan MF, Mahadevan S, Al-Adawi S. Factors associated with mental health outcomes across healthcare settings in Oman during COVID-19: frontline versus non-frontline healthcare workers. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e042030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Zerbini G, Ebigbo A, Reicherts P, Kunz M, Messman H. Psychosocial burden of healthcare professionals in times of COVID-19 - a survey conducted at the University Hospital Augsburg. Ger Med Sci. 2020;18:Doc05. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Dimitriu MCT, Pantea-Stoian A, Smaranda AC, Nica AA, Carap AC, Constantin VD, Davitoiu AM, Cirstoveanu C, Bacalbasa N, Bratu OG, Jacota-Alexe F, Badiu CD, Smarandache CG, Socea B. Burnout syndrome in Romanian medical residents in time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Hypotheses. 2020;144:109972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 31.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Wu Y, Wang J, Luo C, Hu S, Lin X, Anderson AE, Bruera E, Yang X, Wei S, Qian Y. A Comparison of Burnout Frequency Among Oncology Physicians and Nurses Working on the Frontline and Usual Wards During the COVID-19 Epidemic in Wuhan, China. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e60-e65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 319] [Cited by in RCA: 371] [Article Influence: 74.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Chew NWS, Ngiam JN, Tan BY, Tham SM, Tan CY, Jing M, Sagayanathan R, Chen JT, Wong LYH, Ahmad A, Khan FA, Marmin M, Hassan FB, Sharon TM, Lim CH, Mohaini MIB, Danuaji R, Nguyen TH, Tsivgoulis G, Tsiodras S, Fragkou PC, Dimopoulou D, Sharma AK, Shah K, Patel B, Sharma S, Komalkumar RN, Meenakshi RV, Talati S, Teoh HL, Ho CS, Ho RC, Sharma VK. Asian-Pacific perspective on the psychological well-being of healthcare workers during the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Open. 2020;6:e116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Degraeve A, Lejeune S, Muilwijk T, Poelaert F, Piraprez M, Svistakov I, Roumeguère T; European Society of Residents in Urology Belgium (ESRU-B). When residents work less, they feel better: Lessons learned from an unprecedent context of lockdown. Prog Urol. 2020;30:1060-1066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Karasek Jr RA. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q. 1979;24:285-308. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 70. | Dinibutun SR. Factors Associated with Burnout Among Physicians: An Evaluation During a Period of COVID-19 Pandemic. J Healthc Leadersh. 2020;12:85-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Siegrist J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996;1:27-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 354] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Elovainio M, Kivimäki M, Vahtera J. Organizational justice: evidence of a new psychosocial predictor of health. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:105-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 353] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Gómez-Salgado J, Domínguez-Salas S, Romero-Martín M, Ortega-Moreno M, García-Iglesias JJ, Ruiz-Frutos C. Sense of coherence and psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Sustainability. 2020;12:6855. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Rodriguez RM, Medak AJ, Baumann BM, Lim S, Chinnock B, Frazier R, Cooper RJ. Academic Emergency Medicine Physicians' Anxiety Levels, Stressors, and Potential Stress Mitigation Measures During the Acceleration Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27:700-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Suleiman A, Bsisu I, Guzu H, Santarisi A, Alsatari M, Abbad A, Jaber A, Harb T, Abuhejleh A, Nadi N, Aloweidi A, Almustafa M. Preparedness of Frontline Doctors in Jordan Healthcare Facilities to COVID-19 Outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Rodrigues H, Cobucci R, Oliveira A, Cabral JV, Medeiros L, Gurgel K, Souza T, Gonçalves AK. Burnout syndrome among medical residents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0206840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 40.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Ashkar K, Romani M, Musharrafieh U, Chaaya M. Prevalence of burnout syndrome among medical residents: experience of a developing country. Postgrad Med J. 2010;86:266-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Monsalve-Reyes CS, San Luis-Costas C, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Albendín-García L, Aguayo R, Cañadas-De la Fuente GA. Burnout syndrome and its prevalence in primary care nursing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19:59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Gómez-Urquiza JL, De la Fuente-Solana EI, Albendín-García L, Vargas-Pecino C, Ortega-Campos EM, Cañadas-De la Fuente GA. Prevalence of Burnout Syndrome in Emergency Nurses: A Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Nurse. 2017;37:e1-e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Cañadas-De la Fuente GA, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Ortega-Campos EM, Cañadas GR, Albendín-García L, De la Fuente-Solana EI. Prevalence of burnout syndrome in oncology nursing: A meta-analytic study. Psychooncology. 2018;27:1426-1433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Zhang Q, Mu MC, He Y, Cai ZL, Li ZC. Burnout in emergency medicine physicians: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e21462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388:2272-2281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1573] [Cited by in RCA: 1320] [Article Influence: 146.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Hilton LG, Marshall NJ, Motala A, Taylor SL, Miake-Lye IM, Baxi S, Shanman RM, Solloway MR, Beroesand JM, Hempel S. Mindfulness meditation for workplace wellness: An evidence map. Work. 2019;63:205-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Hofmeyer A, Taylor R, Kennedy K. Fostering compassion and reducing burnout: How can health system leaders respond in the Covid-19 pandemic and beyond? Nurse Educ Today. 2020;94:104502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive Leadership and Physician Well-being: Nine Organizational Strategies to Promote Engagement and Reduce Burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:129-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 860] [Cited by in RCA: 1052] [Article Influence: 131.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Blake H, Bermingham F, Johnson G, Tabner A. Mitigating the Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Workers: A Digital Learning Package. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 63.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Geoffroy PA, Le Goanvic V, Sabbagh O, Richoux C, Weinstein A, Dufayet G, Lejoyeux M. Psychological Support System for Hospital Workers During the Covid-19 Outbreak: Rapid Design and Implementation of the Covid-Psy Hotline. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |