INTRODUCTION

The 2019 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics update of the American Heart Association (AHA) reported that 48 percent of persons ≥ 20 years of age in the United States have some form of Cardiovascular Disease (CVD)[1]. In USA, roughly 16.3 million of people have Coronary Heart Disease (CHD)[2], secondly with approximately 7 million of Americans had at least one episode of stroke. Moreover, almost 82.6 million US citizens present at least one or more forms of CVD[2], which encompasses four major areas: CHD, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral artery disease and aortic atherosclerosis as well as thoracic or abdominal aortic aneurysm[1].

Current data suggest that every 36 s Americans die from CVD, accounting for 1 in 4 deaths in the country[3]. Furthermore, this illness it is characterized as a chronic low grade inflammatory condition that has atherosclerosis as its most common pathological substrate. In People living with HIV (PLWH), CVD risk has been shown to be 50% higher than in uninfected individuals[4]. Aside from the well-known risk factors for CVD such as smoking, changes in lipid profile and insulin resistance; HIV infection itself and some side effects of antiretroviral therapy (ART), especially protease inhibitors, are further contributing factors among this population[5-7]. In that sense, Cardiovascular disease (CVD) has become one of the commonest causes of death in the PLWH under treatment with virological and immunological control[8].

Intermittent fasting (IF), consisting of periods of strict calorie restriction (CR) alternating with variable feeding schedules, is a widespread practice gaining high level of interest in the scientific community and the media followed by millions of people around the globe[9,10]. Different regimens of intermittent fasting have been reported in the literature with two of them being the most notorious: Time Restrictive Feeding (TRF), where the fasting period is about 14-20 h/d, and Alternate d Fasting, traditionally 2 d fast/5 d fed[9,11,12]. It is important to remark that intermittent fasting does not necessarily involve limiting the total number of daily calories as in a typical caloric restriction regimen; therefore, it may be implemented in pathologies that do not require a reduction in the number of calories ingested[12]. Multiple potential benefits of IF have been described such as improvement in glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity, weight loss, delayed aging, systemic inflammation, beneficial neurocognitive effects and cardiovascular benefits[12,13]. Additional metabolic benefits are still being investigated with promising paths for future research[12].

To the best of our knowledge, there is a large literature on the benefits of IF in cardiovascular disease, but none on the case of PLWH. Therefore, we aimed to explore the potential role of intermittent fasting as a non-pharmacological and cost-effective strategy in decreasing the burden of cardiovascular diseases among HIV patients on ART due to its intrinsic properties improving the main CVD risk factors and modulating the systemic inflammatory state.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

People living with HIV are almost 38 million distributed throughout all the continents[14]. PLWH on ART are disproportionately affected by an increase in the incidence of CVD compared with age-matched HIV-negative controls[4]. To date, it is known that people living with HIV present more than twice increased risk of cardiovascular disease in general[4,14]. For instance, from 1999 to 2013 the rate of deaths in the US caused by CVD in PLWH increased from 2% to almost 5%[15]. Furthermore, CVD is one of the main non-AIDS- related complications, since between 9% and 20% of PLWH in developed countries are at moderate to high risk of suffering a myocardial infarction (MI)[16].

Lately, there has been an increase prevalence of smoking in the HIV population which could be explained by a variety of factors including anxiety and other mental illnesses, alcohol and illicit drug use, sociodemographic stressors due to social discrimination, increased risk-taking behaviors and impulsiveness, or false perception of smoking risks[17,18]. It was seen in a Danish study that HIV smokers had a higher relative risk of suffering a Myocardial infarction (MI) compared to negative controls[19]. Furthermore, some of the ART regimens that include protease inhibitors (PIs) can also contribute to the increase in the incidence of CVD[7]. On a different note, the fact that the Framingham Score underestimates the MI risk in PLWH, which was clearly observed in a cohort study, complicates even more the early detection and treatment[20]. The intensity of CVD in HIV patients (measured objectively as Intimal Media Thickness = IMT) may also be directly related to the HIV duration, meaning that the arterial damage is most likely accumulative over the years[21]. The accelerated atherosclerosis formation is thought to be independent of viral replication (at least in plasma) and multifactorial[22-26] being the microbial translocation at the level of the Gut-mucosa one of the main culprits and generators of chronic inflammation[21,27-30].

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

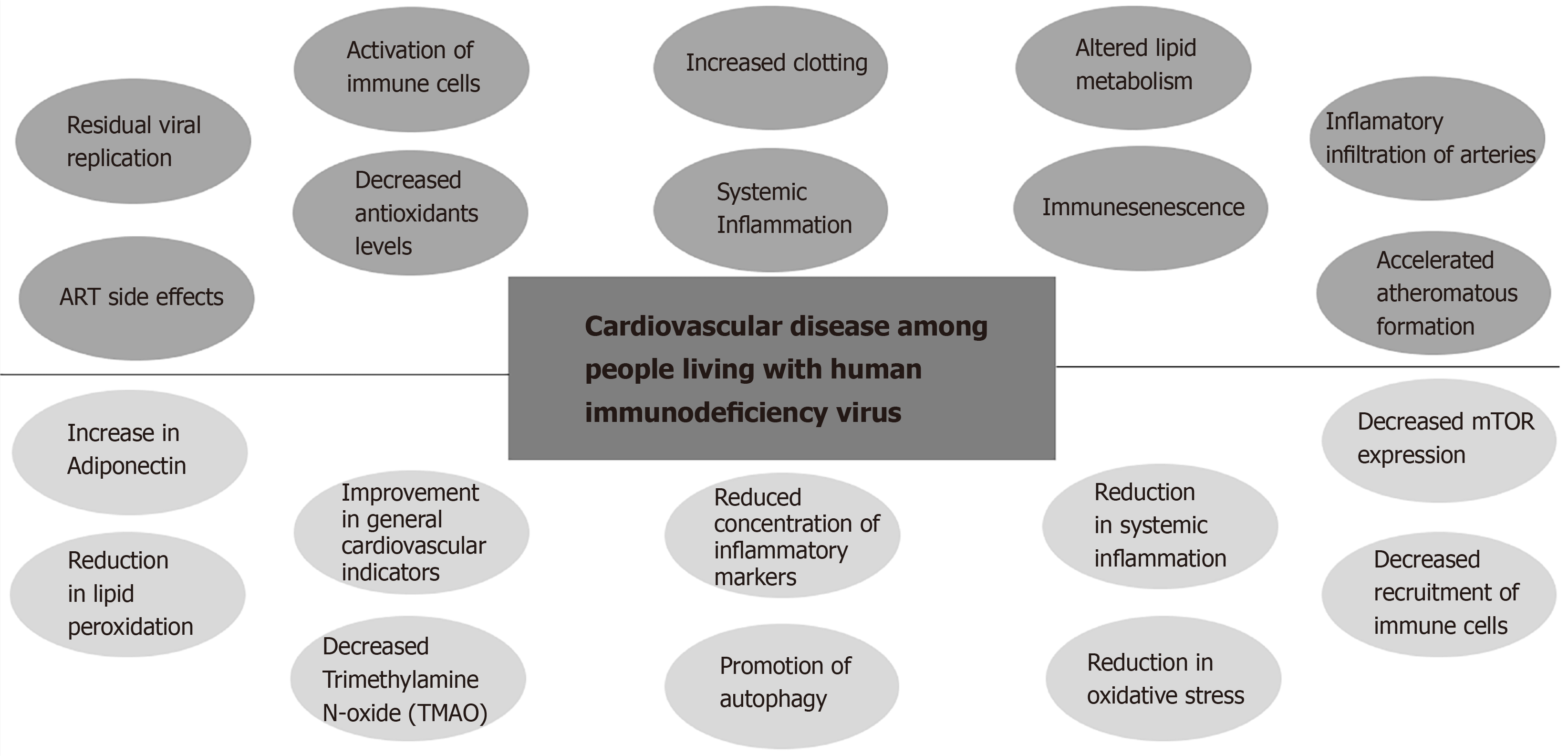

The increase in the CVD risk on PLWH can be explained due to the significant increase of systemic inflammation and immune-activation compared to HIV uninfected controls even in the presence of effective ART (Figure 1). Other identified contributing factors are increased clotting, altered lipid metabolism, macrophage/T-cell infiltration of arteries, residual viral replication, direct toxicity of ART, and immune-senescence[29,31]. Early immune senescence may contribute directly to accelerated CVD since senescent cells promote the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (termed "senescent-associated secretory phenotype or SASP")[32]. In that sense, it was found that elimination of senescent cells from prematurely aged mice prevented aging of some organs[32]. Also, HIV is associated with decreased levels of antioxidants such as ascorbic acid, tocopherols, selenium, superoxide dismutase, and glutathione[33,34] along with an increase in the levels of hydroperoxides and malondialdehyde[35]. In addition, peroxides and aldehydes are not only passive markers of oxidative stress, but also really toxic compounds for cells being lipid peroxidation and LDL oxidation involved in the pathophysiology of CVD[36]. Endothelial dysfunction is associated with many of the traditional risk factors for atherosclerosis described above. The endothelial dysfunction is induced by oxidized low density lipoprotein (LDL) and should be considered as a common final pathway of multiple vascular insults[37]. On the other hand, metabolic side effects of ART are continuously being updated. Besides the well described metabolic side effects of some Protease inhibitors, new concerns regarding weight gain and subsequent metabolic disturbances are raising with the use of first line drugs such as Tenofovir Alafenamide (TAF) and Integrase strand transfer inhibitors (Raltegravir, Elvitegravir (EVG), Dolutegravir (DTG), and Bictegravir (BIC)[38]. The combination of the later generation ISTIs (Dolutegravir and Bictegravir) along with TAF presents the highest risk[38] (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Summary of the interplay of the human immunodeficiency virus- antiretroviral therapy related contributing factors to cardiovascular disease and intermittent fasting potential benefits among People living with human immunodeficiency virus.

The genesis of inflammation and immune-activation in PLWH most likely starts at the Gut-mucosal level early after the infection. It has been extensively studied that simian immunodeficiency virus SIV (in non-natural hosts) and HIV infection lead to breaches in the tight junctions between epithelial cells in the gut mucosa that allow microbial products, and chemokines to cross over[36,39-41]. These abnormalities are not only anatomical but functional as well. It is well known that bacterial products from the “gut-microbiome” like lipopolysaccharides (LPS) can stimulate the innate immune system through the pattern recognition receptors such as toll-like receptors (TLRs) mainly TLR-4 generating a local and systemic proinflammatory state[36,39]. Actually, it has been shown that an increase in the sCD14 (a soluble marker of monocyte activation after binding to LPS) predicts early mortality in HIV patients[42]. This finding is the first link between microbial translocation and mortality on HIV individuals particularly related to CVD.

The increased systemic inflammation and immune-activation in PLWH can be objectively measured through a specific cytokine profile. In HIV patients on effective ART with excellent immunological response (CD4 cell count > 500), fibrinogen and C-reactive protein (CRP) still remain strong and independent predictors of mortality[43]. In addition, interleukin 6 (IL-6), CRP, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interferon gamma (IFN-gamma) and D-dimer all remain elevated even after effective ART[44]. It was shown that elevated CRP and HIV are independently associated with increased myocardial infarction (MI) risk, and that patients with HIV with increased CRP have a markedly increased relative risk of MI. Similarly, IL-6 and D-dimer were strongly related to all-cause mortality in this population[45]. Also, chemokines like interleukin 8 (IL-8), Regulated upon Activation Normal T Cell Expressed and Presumably Secreted (RANTES), C-C motif ligand 2 (CCL2), and interferon gamma- induced protein 10 (IP10) remain elevated in PLWH[46], which is evidence of active recruitment of immune cells to the plaque. The above points toward a well-defined mechanism of accelerated atheromatous formation in PLWH related to systemic inflammation and local recruitment of inflammatory cells to the atheromatous plaque, a process that starts off at the level of HIV-associated gut mucosal dysfunction.

INTERMITTENT FASTING AND PREVENTION OF CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE IN HUMAN STUDIES: TRANSLATION TO PLWH

Multiple strategies directed to decrease inflammation and immune-activation in PLWH on effective ART have shown partial and non-definitive results. In an attempt to look for nutritional and non-pharmacological approaches to face this problem, IF looks extremely attractive. IF has shown to decrease the CVD risk either directly (through improvement on the main CV risk factors) or indirectly (decreasing inflammation, immune-activation, immune cells migration, Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) formation, and local oxidative stress)[12,47,48] (Figure 1). Multiple animal studies of IF have consistently proven to increase lifespan, decrease inflammation, treat diabetes and other metabolic diseases, improve cardiovascular health, and promote innumerable neurocognitive benefits (including neuro-protection against stroke) which has been described in detail in previous reviews by Mattson, M. and Longo[47,48]. Even though there is less robust evidence in human studies, multiple recent clinical trials have proven that IF decreases the overall CV risk through the improvement of each of its main modifiable risk factors. There is some discussion as to whether the decrease in the CVD risk with IF is due to its intrinsic characteristics or due to the weight loss secondary benefits. Of note, a very recent clinical trial showed the health benefits regardless of the daily calorie intake in a group of patients with metabolic syndrome[49]. As explained before, the health benefits are beyond weight loss since IF not necessarily implies a decrease in the daily caloric intake.

Direct Mechanism: improving modifiable traditional CVD risk factors

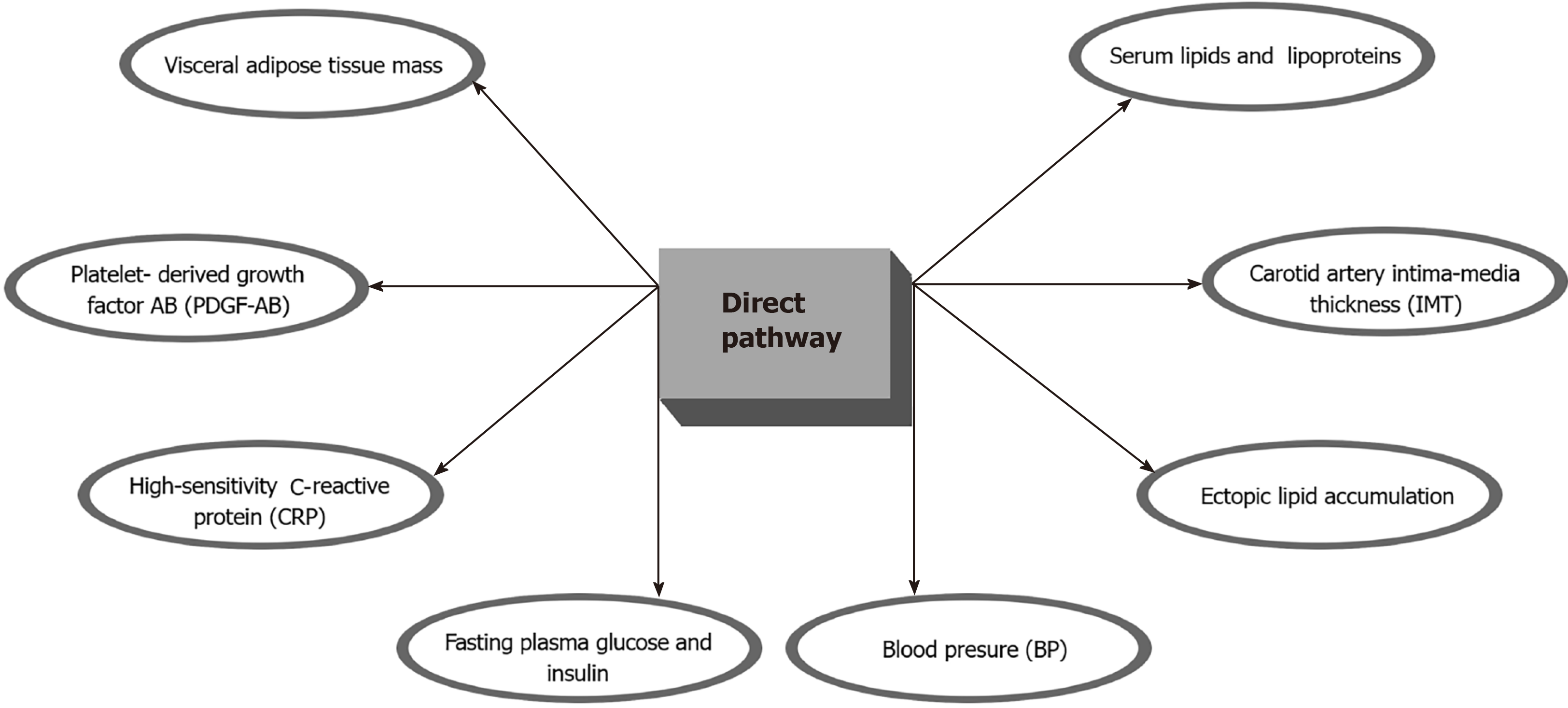

A recent study showed that a scheduled calorie restriction and IF (24 mo) in healthy, non-obese individuals was proven to be beneficial in improving risk factors for cardiovascular and metabolic disease such as visceral adipose tissue mass, ectopic lipid accumulation, blood pressure, and lipid profile, but improvements in insulin sensitivity were only transient[50]. Individuals that had been in a prolonged calorie restriction (CR) program had better outcomes in terms of serum lipids and lipoproteins, fasting plasma glucose and insulin, blood pressure (BP), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP), platelet-derived growth factor AB (PDGF-AB), body composition, and carotid artery intima-media thickness (IMT). Importantly, patients that were in the CR group had 40% less IMT, which is an important surrogate for coronary artery disease[51] (Figure 2). A very recent comprehensive review by Mattson M et al[52] showed that IF improves multiple indicators of cardiovascular health including blood pressure, resting heart rate, LDL and HDL levels, cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose and insulin resistance. The same review encouraged practitioners to start applying this strategy to patient care always under close professional supervision and progressively over weeks or months. Another recent study (single-arm, paired-sample trial) showed that 19 participants with metabolic syndrome who were exposed to a TRF (Time Restricted Feeding) protocol on which they ate for only 10 h, showed significant improvements in health indicators including: weight loss; reduced waist circumference, percent body fat, and visceral fat; reduced blood pressure, atherogenic lipids, and glycated hemoglobin[49]. Since PLWH are disproportionately affected by the traditional reversible CV risk factors IF could provide a significant improvement of health indicators, improvement in quality of life, and a marked reduction in the risk of CVD (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Summary of the potential benefits of the direct intermittent fasting pathway among People living with human immunodeficiency virus.

Indirect mechanisms

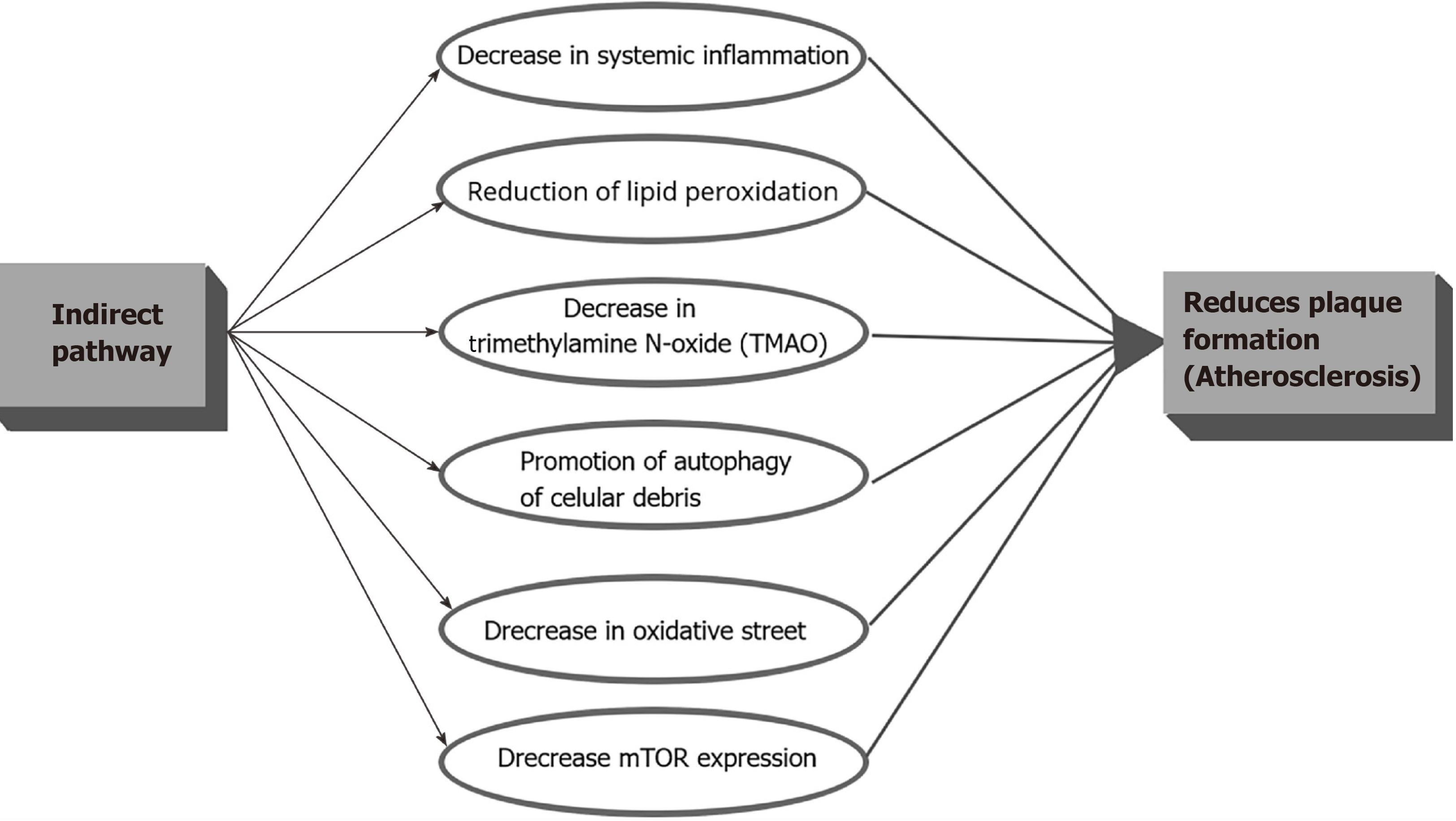

Indirectly, IF can decrease the CVD risk in PLWH through the decrease in systemic inflammation, reduction of lipid peroxidation, decrease in Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), promotion of autophagy of cellular debris, and decrease in oxidative stress which in turn, shall decrease the accelerated atheroma plaque formation (Figure 3). It is important to clarify that even though IF showed much of its anti-inflammatory properties in animal studies, HIV patients present inflammatory levels way above the mean levels compared with HIV negative controls which means that any change may correlate with a significant decrease in the CVD risk and clinical events. Trimethylamine N-oxide is an amine oxide produced in humans by intestinal microbiota from excess trimethylamine (TMA), and intermediate of choline metabolism. It has been linked to increase inflammation in adipose tissue and accelerate atherosclerosis[53]. A mean level of 14.3 ng of TMAO during fasting versus a baseline mean of 27.1 ng in control subjects (P = 0.019) was found in an IF study in humans[54], which means than IF can have implications on decreasing inflammation in the atheromatous plaque not only by decreasing the recruitment of activated monocytes but by decreasing the TMAO levels.

Figure 3 Summary of the potential benefits of the indirect intermittent fasting pathway among People living with human immunodeficiency virus.

This ancient mechanism was probably not only created to use alternative sources of energy when food is lacking but also to clear cells from toxic molecules, reactive oxygen species (ROS), deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) damage, and cellular debris probably through autophagy. As we explained above, oxidative stress and decreased antioxidants with lipid peroxidation is important for the plaque formation (Figure 3). The anti-atheroma formation mechanisms of IF may be mediated through: Possible endothelial improved cellular stress adaptation to ischemia and inflammation (mainly against ROS generation), decreased DNA damage, decreased inflammation, decrease recruitment of immune cells, decrease mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) expression[47], and promoting autophagy. In rats exposed to IF in stroke experimental models (which causes brain inflammation), decreases of Interleukin 1 beta (IL1-b), TNF-alpha, IL-6, and suppression of the "inflammasome" was observed[55]. IF also resulted in reduced levels of messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNAs) encoding the LPS receptor TLR4 and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in the hippocampus of rats exposed to systemic LPS. Moreover, in another study IF prevented the LPS-induced elevation of IL-1α, IL-1b, IFN-γ, RANTES, TNF-α and IL-6[56]. Those two studies could have implications to decrease the LPS-driven activation of TLRs in innate immune cells, and, hence, gut inflammation in PLWH. The decrease in the gut inflammation shall decrease monocyte activation, migration, and generation of CD14’s, which is directly implicated in the accelerated atheromatous plaque formation (Figure 3). IF could interrupt the "Gut-Heart axis" and significantly decrease the endothelial dysfunction. Following the same line of thoughts, IF may also inhibit the development of the atheroma plaque in HIV patients by reducing the local concentration of inflammatory markers, such as IL-6, homocysteine, and CRP, and, at the same time, decreasing the migration of immune cells to the subendothelial area through the increase of adiponectin[57]. Recently was shown that isocaloric TRF (Time Restricted Feeding) during 8 wk in males, reduced many markers of inflammation such as TNF alpha, IL-6, and IL-1b, and, increased adiponectin (an anti-inflammatory cytokine)[58]. Considering that this was a study in healthy human subjects and due to the fact that the HIV patients on ART have much higher levels of inflammation, the decrease in the CVD risk could be clinically significant. There are no theoretical biological barriers for which the above physiologic events would not happen in PLWH exposed to IF.

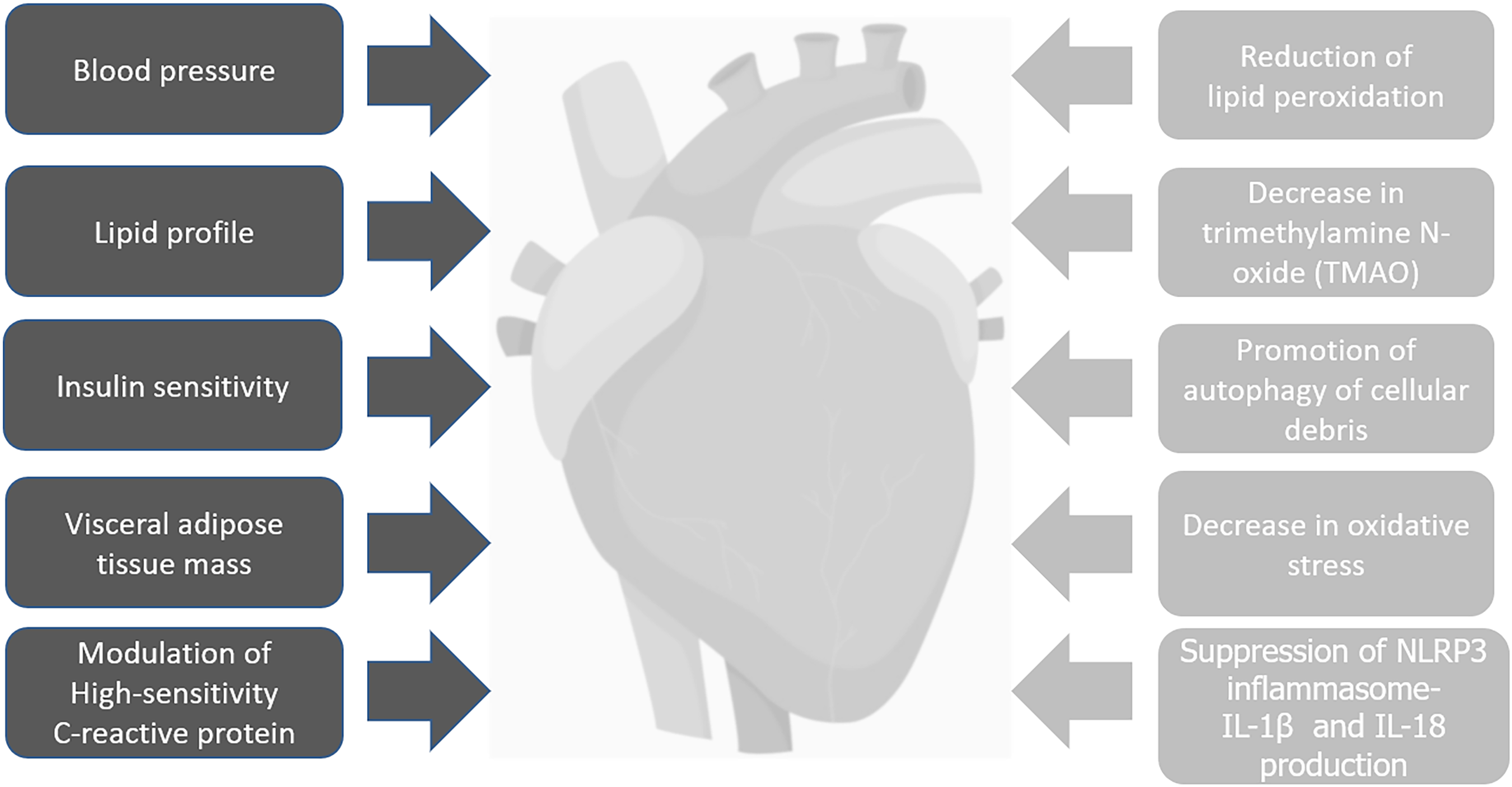

To understand the pathophysiology of chronic inflammation some big players need to be explained more in detail. The NLRP3 inflammasome is a multiprotein platform which is activated by infection (including HIV) or some sort of cellular stress (including ischemia). Its activation leads to caspase-1-dependent secretion of proinflammatory cytokines like interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-18, and leads to an inflammatory form of cell death termed as “Pyroptosis”[59]. The inflammasome activation as a generator of inflammation will contribute to the increased CVD risk. The inflammasome can be activated directly by HIV through TLR8 activation after contact with viral RNA[46] but also by other TLRs-mediated pathways (like TLR4 with LPS in the gut mucosa as explained above). It was proved that the ketone bodies β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) and acetoacetate, both elevated during starvation, inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome. BHB and acetoacetate were shown to reduce the NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18 production in human monocytes[60] which will be extremely important for latently-HIV-infected monocytes to prevent activation and further recruitment with migration to the atheroma plaque. In another experimental model in rats with an experimentally induced stroke (which causes local inflammation), IF could attenuate the inflammatory response and tissue damage by suppressing NLRP1 and NLRP3 inflammasome activity[61]. A stressed Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) is known to generate ROS which, in turn, activates the NLRP3 inflammasome and secretion of IL-1b. A recent study in rats also showed a potential therapeutic role of β-hydroxybutyrate in suppressing the ER (stressed)-induced inflammasome activation[62]. It was revealing the study that showed that patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) had significant clinical improvement (pain and inflammation) after a period of fasting if a vegetarian diet was followed thereafter[63]. Another study in overweight asthmatic female patients exposed to IF showed a significant decrease in the levels of TNF-alpha and markers of oxidative stress (8-isoprostane, nitrotyrosine, protein carbonyls, and 4-hydroxynonenal adducts) with improved clinical response. It showed that prolonged fasting blunted the NLRP3 inflammasome and T Helper 2 (Th2) cell activation in steroid-naive asthmatics as well as diminished the airway epithelial cell cytokine production[64]. These two studies highlight the possibility of using the “survival-mode” of IF to fight chronic inflammatory conditions, which, in turn, promote accelerated aging and CVD. In fact, HIV is a perfect example of a chronic inflammatory disease. We think that in all these conditions (RA, Asthma, and HIV) the baseline level of inflammation is so high that any change will have significant clinical implications. There is no reason to think that the decreased levels of inflammation seen in these two studies will not be translated to PLWH, and, actually, it may be exacerbated. The decrease in the migration of inflammatory cells to the atheromatous plaque during IF is due to the decrease in the expression of the vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecule 1 (ELAM-1), and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) on vascular endothelial cells - all molecules highly implicated in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis-[57]. Migration and trafficking of activated immune cells are highly involved in the pathogenesis of CVD in PLWH (Figure 4). Interestingly, Proteobacteria was identified as one of the main producers of TMAO which is increased in the dysbiosis caused by HIV[53]. IF may in fact cause a reversal of the HIV- associated - dysbiosis with decrease in the Proteobacterias (mainly inflammatory and Pro-glycolytic) with possible switch to a healthier microbiome (with less production of TMAO) like Lactobacillus and Firmicutes (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 4 Summary of the direct (black) and indirect (gray) mechanisms of intermittent fasting in cardiovascular disease in People living with human immunodeficiency virus.

OTHER DIETARY REGIMENS AND HIV

Different dietary regimens have been evaluated with mixed results in PLWH on ART. A recent systematic review explored the potential benefits of micronutrients including but not limited to Vitamin A, D, Zinc, and Selenium[65]. The administration consisted in either each macronutrient or in combination. However, after a period of follow up to 6-18 mo, the study revealed minimal or no relevant benefits[65]. Another study compiled the interventions of some diets such as low-fat diet, hypocaloric diet, omega-3 fatty acids, carnitine, micronutrient supplements, formula, amino acids, uridine, among others, on HIV-infected patients receiving combination antiretroviral therapies. Where oral nutrition support (protein and energy intake) has been demonstrated to promote weight gain and fat mass overall[66]. Besides this, formula supplementation has not demonstrated further benefits. Whereas amino acids in combination showed to increase lean body mass in HIV-infected patients undergoing weight loss. The use of a low-fat diet was suggested to be implemented carefully and tailored accordingly in order to avoid a severe reduction in body mass[66,67]. Despite the paucity of controlled randomized trials with larger sample sizes, above results in small but significant findings. Further larger randomized blinded clinical trials are needed to ensure confirmatory results.

When it comes to assessing diet adherence among PLWH, it was previously seen in a study that overweighted HIV positive individuals tend to have a higher adherence to Mediterranean diet compared to the rest of the group[68]. It is hypothesized that due to the moderate risk of CVD and a diagnosis of metabolic syndrome, there is an increased awareness towards a healthier food pattern to avoid further complications[68]. In that sense, when introducing IF to PLWH we believe that adherence will not be a real problem indeed and PLWH with higher risk factors would be more prone to adhere to the new dietary regimen. Nevertheless, nutritional education strategies should be implemented early and routinely to optimize adherence among patients.

FUTURE TRIALS IN PLWH AND POTENTIAL CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

To the best of our knowledge this is the first review addressing the possibility of applying IF in PLWH on effective ART. Due to the evidence presented above and due to the fact that PLWH are aging with increased prevalence of CVD, IF strategies need to be tested in clinical trials through proof-of-concept studies or large prospective randomized clinical trials. There are no obvious absolute contraindications that we can think of besides the obvious harm associated with extreme weight loss in patients with AIDS and wasting syndrome being off ART. Inclusion and exclusion criteria will need to be carefully defined in prospective clinical trials in order to be safe.

IF studies did not include pregnant women and were not tested in the extremes of age (pediatrics or frail elderly subjects) in which case its use is discouraged and the possible consequences are unknown. One caveat is that some HIV medications needs to be ingested with food and not on an empty stomach, but given the posology of current antiretrovirals (1 or two pills a d usually once daily in naïve patients) the recommendation would be to take the medication when the patient ingest the first meal of the d (when the patient "breaks the fast"). In the case of more complex regimens in PLWH with multidrug resistance and twice daily regimens personal accommodations will need to be taken into account. Monthly injections of Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine were recently approved on which case IF protocols will be easier. However, first line initial regimens for most people with HIV -which generally consists of the combination of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) with an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI)-, suggest to use the combination of Bictegravir, Tenofovir alafenamide and Emtricitabine (BIC/TAF/FTC)[69]. Current indications from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) suggest taking the drugs with or without food[70-72]. Rilpivirine (oral formulation only) regimens, in the contrary, will require a high caloric meal to increase its absorption when the feeding window starts.

Ruling out any impediment with the practice of IF within these patients. Of note, this strategy that we propose will need to be applied only to PLWH on stable ART with immunological and virological response (< 20 copies in two different occasions at least 6 mo apart in a stable regimen with good CD4 response which is not well defined but definitely more than 200 cells or more than 14%), without active opportunistic infections, active malignancy, malnourishment, or any other chronic debilitating disease. The inclusion and exclusion criteria will need to be clarified in detail by future investigations since this is a new concept so far unexplored. For sure, pregnancy and extremes of age with frailty and weight loss will be excluded during the initial trials.

CONCLUSION

The burden of Cardiovascular Diseases among HIV patients on ART is continuously growing. Intermittent fasting, through direct and indirect mechanisms, could play a role in the management and prevention of CVD among PLWH on ART. If these concepts are proven to be true in future clinical trials IF could be considered as an extremely important, cost-effective and revolutionary coadjutant of ART in the fight against the increased prevalence of CVD in PLWH which could, in turn, improve survival, decrease CV clinical events, and improve quality of life. Therefore, we recommend further longitudinal and experimental studies to ensure the safety, efficacy and effectiveness of IF on CVD among PLWH.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hazafa A S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yu HG