Published online Feb 28, 2014. doi: 10.5319/wjo.v4.i1.1

Revised: October 28, 2013

Accepted: December 9, 2013

Published online: February 28, 2014

AIM: To evaluate the role of drains in clamp-and-tie total thyroidectomy (cTT) for large goiters.

METHODS: A hundred patients were randomized into group D (drains maintained for 24 h) and ND (no drains). We recorded epidemiological characteristics, thyroid pathology, hemostatic material, intraoperative events, operative time and difficulty, blood loss, biochemical and hematological data, postoperative vocal alteration and pain, discomfort, complications, blood in drains, and hospitalization.

RESULTS: The groups had comparable preoperative characteristics, pathology, intraoperative and postoperative data. Hemostatic material was used in all patients of group ND. Forty patients in group D and 9 in ND felt discomfort (P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION: Drains in cTT for large goiters give no advantage or disadvantage to the surgeon. The only “major disadvantage” is the discomfort for the patient. Inversely, drains probably influence surgeons’ serenity, especially when cTT is performed in nonspecialized departments.

Core tip: The present aim is to elucidate the significance of drains in thyroid surgery for large goiters in the modern era. The authors conclude that there are two major parameters that influence the placement of drains: the surgeon’s experience and the patient’s discomfort.

- Citation: Papavramidis TS, Pliakos I, Michalopoulos N, Mistriotis G, Panteli N, Gkoutzamanis G, Papavramidis S. Classic clamp-and-tie total thyroidectomy for large goiters in the modern era: To drain or not to drain. World J Otorhinolaryngol 2014; 4(1): 1-5

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6247/full/v4/i1/1.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5319/wjo.v4.i1.1

Total thyroidectomy (TT) is nowadays considered a “routine” operation in specialized endocrine departments. This operation can be performed either by classic incisions (Kocher or Sofferman) or by minimal scar techniques. Conventional clamp-and-tie thyroidectomy consists of devascularization of the thyroid by double ligating and dividing the branches of the thyroid vessels, followed by excision of the gland. During thyroid surgery, adequate hemostasis and keeping the operative field dry and clean is of utmost importance. Suture ligations are time-consuming, carry the risk of knot slipping, and are not suitable for endoscopic surgery[1]. For that reason, new energy sources and methods of hemostasis have been used in the last years in thyroid surgery with great effectiveness. However, the classic clamp-and-tie thyroidectomy has not been abandoned and is frequently employed in general surgery departments, either due to the unavailability of new technologies or to a lack of training in other techniques. Whatever the method of hemostasis, when TT is performed, it is of prime importance to achieve accurate and efficient hemostasis in order to minimize complications.

Since meticulous hemostasis is of prime importance in every type of thyroid surgery, the use of draining tubes seems paradoxical. With small volume goiters, the above statement may be true; however, this is not the case in large goiters, especially those performed with the classic clamp-and-tie technique. From that perspective, the present prospective randomized trial was designed, aiming to evaluate the necessity of drains when a clamp-and-tie total thyroidectomy (cTT) is performed for a large goiter.

The present prospective randomized trial was approved by the ethics committee of AHEPA University Hospital. It was registered to ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT00691990). The registration period for the study lasted from 1st July, 2008 to 31st December, 2010.

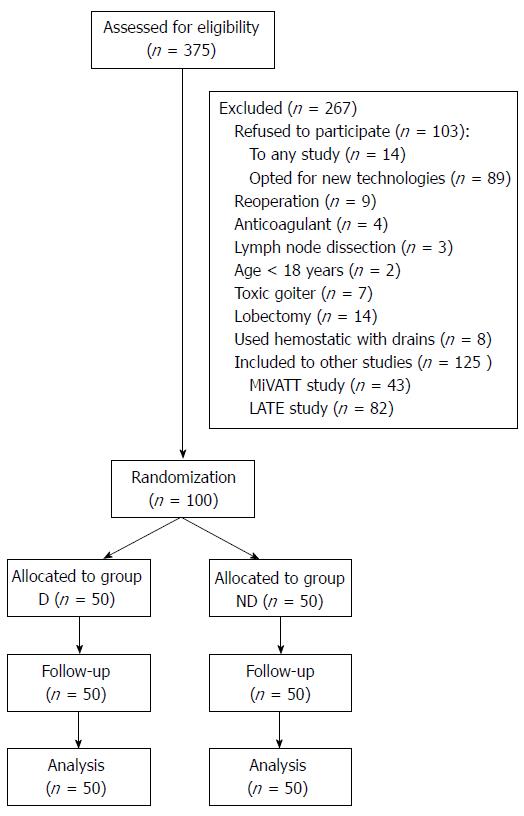

The inclusion criteria were: (1) acceptance to participate in the study (signed informed consent form); (2) age > 18 years; and (3) a scheduled cTT. The exclusion criteria were: (1) participation in another clinical trial which affects outcomes (small volume thyroids < 50 mL were included in other studies); (2) a previous thyroid operation; (3) a toxic condition; and (4) anticoagulation treatment. Figure 1 displays the flow diagram of the study. One hundred adult patients with benign or malignant thyroid disease scheduled for classic total thyroidectomy at the 3rd Department of Surgery of AHEPA University Hospital of Thessaloniki were randomized into 2 groups according to whether drains were going to be used (group D) or not (group ND). Randomization was performed by using computer-generated tables immediately after the assessment for eligibility.

Classic TT was performed with patients in the supine position with the head slightly hyperextended[2]. All procedures were performed by a team dedicated to endocrine surgery. Preoperative laryngoscopy was performed in all patients to assess vocal cord motility. A 4 cm cervicotomy was performed. Ligatures were done with resorbable 4-0 vicryl ligatures; in group D, a 14 French negative pressure drain was placed, whereas in group ND no drain was placed. Both groups received 2 doses of 40 mg parecoxib sodium, one at the end of the operation and one 12 h later. Anesthesia was standardized following the protocol proposed by Andrieu et al[3]. Patients were premedicated with hydroxyzine (1.5 mg/kg orally) 2 h before surgery. General anesthesia was induced using propofol (2-3 mg/kg) and sufentanil (0.3 mg/kg). Tracheal intubation was facilitated by the administration of atracurium (0.5 mg/kg). General anesthesia was maintained with sevoflurane (0.5%-1.8%) in an oxygen-nitrous oxide mixture (60/40%). The sevoflurane was adjusted to maintain a bispectral index (Aspect Medical Systems, Inc., Newton, MA) between 40 and 60. Additional doses of sufentanil (0.15 mg/kg) were administered for variations of systolic blood pressure and heart rate of > 20% when compared with the values measured before operation.

The following data were recorded: age, gender, body mass index, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) status, medications, thyroid pathology and weight, use of hemostatic material, intraoperative events/complications, duration of the operation, intraoperative blood loss, operative difficulty, calcemia (preoperative, postoperative), preoperative and postoperative standard biochemical and hematological data (SGOT, SGPT, LDH, Glc, Ure, Cre, K+, Na+, Mg2+, TP, ALB, fT3, fT4, TSH, PTH, PT, aPTT, INR, Ht, Hgb, WBC), preoperative and postoperative vocal motility, postoperative vocal alteration, postoperative pain, discomfort, complications, blood in the drains, and length of hospital stay.

Operative difficulty was assessed by a rating scale ranging from 1 (very easy) to 5 (very difficult). Postoperative voice alteration was assessed by a VAS, ranging from 1 (no voice alteration) to 10 (worst imaginable alteration). Postoperative pain was assessed by a visual analogue scale (VAS), ranging from 1 (no pain) to 10 (worst imaginable pain). Pain and voice alterations were evaluated by the patient, whereas operative difficulty was assessed by an observing surgeon. The observing surgeon was the same for all operations. Discomfort was evaluated using a yes or no question.

Calcemia was determined every postoperative day until hospital discharge. Clinical hypocalcemia was defined as total calcium < 8.2 mg/dL, associated with a positive Chvostek or Trousseau sign or a patient complaint of paresthesia.

A total of 375 patients were assessed for eligibility but only 100 were included in this trial (Figure 1). The volunteers were divided into two groups. The epidemiological characteristics of both groups are presented in Table 1. Both groups were comparable preoperatively concerning age, male/female ratio, body mass index and ASA score.

| Group D(n = 50) | Group ND(n = 50) | |

| Sex (male/female) | 4/46 | 6/44 |

| Age (yr) | 47.0 ± 5.6 | 51.4 ± 10.5 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.35 ± 5.15 | 28.08 ± 6.06 |

| ASA score | 1.64 ± 0.71 | 1.42 ± 0.67 |

| Pathology | ||

| Benign | 43 | 45 |

| Malignant | 7 | 5 |

| Thyroid weight (g) | 51.8 ± 34.5 | 49.4 ± 34.4 |

| Use of hemostatic material | No | Yes |

| Duration of operation (min) | 98.5 ± 14.1 | 94.6 ± 13.9 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 26.7 ± 18.9 | 24.8 ± 21.3 |

| Blood in the drains (mL) | 76.3 ± 44.4 | - |

| Operative difficulty | 1.90 ± 0.54 | 1.96 ± 0.53 |

| Pain VAS score | 1.58 ± 1.60 | 1.68 ± 1.59 |

| Discomfort | 40 | 9 |

| Complications (no of patients) | ||

| Transitory RLN palsy | 1 | 1 |

| Transitory hypoparathyroidism | 7 | 5 |

| Bruising | 1 | 4 |

The pathology evaluation revealed benign disease in 88 patients (43 in group D and 45 in group ND) and malignant disease in 12 patients. Intraoperative blood loss, duration of the operation and operative difficulty were comparable for both groups. Hemostatic material was used in all of the patients in group ND. The suction drain was maintained for 24 h in all group D patients regardless of the content of the drains.

There was no postoperative hemorrhage with compromised airway in any patient. Thus, surgical evacuation of the hematoma was not required. From this perspective, 4 patients in group ND and 1 patient in group D presented with bruising in the area of operation. The levels of postoperative pain (measured in the VAS scale) were comparable between the two groups. Permanent unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) injury was not observed; however, transient RLN palsy was noticed in 1 patient in each group. Permanent hypoparathyroidism was not observed in any patient; however, transient hypoparathyroidism occurred in 12 patients (7 in group D and 5 in group ND). Those patients were treated as pre-planned (see section material and methods). Finally, 40 patients from group D and 9 patients from group ND felt discomfort (P < 0.001).

Drains or no drains after thyroid surgery This seems to be an obsolete question for specialized units in thyroid surgery. New technologies and hyperspecialization make the answer appear obvious: no drains. However, the above mentioned two conditions are not fulfilled for the majority of patients and the majority of departments. Most patients around the globe are operated on in general surgery departments that perform the classic clamp-and-tie technique with no advanced hemostatic devices. By performing this clinical trial, we aim to evaluate the effect that drains have when executing a classic clamp-and-tie thyroidectomy for large goiters (more than 50 mL).

When designing the present study, we included only patients scheduled for cTT in order to establish a homogenous population. In this way, the effects of new hemostatic technologies and the effect of partial thyroidectomies were eliminated. No patients with a previous operation of the thyroid gland were included to avoid possible alteration of the regional anatomy. Additionally, patients participating in other clinical trials that could potentially affect this study’s outcomes were also excluded (e.g., patients with preoperative thyroid volumes less than 50 mL). Patients receiving anticoagulation treatment for other medical conditions were excluded in order to minimize the probability of bleeding due to anticoagulation treatment. For the same reason, we excluded the 7 patients screened that were not in euthyroid condition (toxic). What is noteworthy is that we expected a higher percentage of acceptances to participate in the study. Surprisingly, 89 patients (24.25%) refused to participate in the study because they opted for the use of new technologies. Happily, this seemed to have no impact on the studied population characteristics. This was further confirmed by the fact that the epidemiological characteristics of the present study are comparable to our previous studies[2,4-6]. We should, however, notice that patients exhibit a clear preference towards total thyroidectomies performed using new technologies rather than the classic clamp-and-tie technique, even when assured that complication rates and hospitalization are comparable[2,4].

Complications associated with thyroid surgery occur regardless of the technique employed. Nowadays, there are two major complications related to total thyroidectomies: iatrogenic hypoparathyroidism and RLN palsy[7]. One of the primary aims of this study was to examine whether drains altered the occurrence of these two major complications in any way. As mentioned in the results section, the present study supports the fact that the incidence of major complications is not altered in any way by the usage of drains. This data is in accordance with previous clinical trials[8-17]. On the other hand, among the rare complications following thyroidectomy, but without doubt the most serious, is postoperative hemorrhage with the potential for tracheal compression, airway involvement and death. Immediate or early hemorrhage occurs in a small percentage[18]. Additionally, postoperative hematoma remains a more or less unknown and unpredictable event with a possibility of subsequent respiratory distress[19]. The rate of postoperative bleeding with formation of a hematoma has been reported to be 0.1%-4.3%, with the rate for symptomatic hematomas being 0.1%-1.0%[20,21]. The present study indicates a 5% rate of asymptomatic hematomas without any symptomatic ones. This marginally increased incidence is probably due to the increased volume and weight of the thyroids excised in this study (see inclusion criteria). What is noteworthy, however, is that there is no statistical difference between the two groups concerning hematomas (bruising). So, from this point of view, the presence or not of a drain has no influence on hematoma formation occurrence.

The time frame for observation after total thyroidectomy is changing[18]. Schwartz et al[22] described a critical period of time in which bleeding occurs most commonly (in all cases, the potential for airway compromise was identified within 4 h of surgery). Accordingly, Burkey et al[23] found that 43% of hematoma presentations were within 6 h, 38% between 7 and 12 h, and 8% after 24 h or more. Many studies agree that late hematomas are uncommon and the large majority of hematomas occur in the earlier period[18,23-25]. It has been shown that late hematomas (> 24 h) occurred only in patients with resection of substernal goiters and who had cardiac co-morbidity that required anti-coagulation/anti-platelet therapy[7]. Postoperative drains allow withdrawal of postoperative hemorrhage. However, they cannot be considered a substitute for meticulous surgical dissection and hemostasis and may predispose to postoperative infection. Under these perspectives, it seems very logical that the use of drains does not alter the duration of hospitalization, as proved in this study. Most surgeons remove the drains after 24 h and send the patient home.

From all of the above, we can actually see no disadvantage or advantage in the use of drains in thyroid surgery. Why then do we observe surgeons with similar experiences following different strategies Two parameters have to be taken into consideration when thinking around this subject: patients’ discomfort and surgeons’ serenity. We found no study to date that correlates patients’ discomfort and the presence of drains in any way. We observed that drains were positively correlated with discomfort. On the other hand, surgeons’ serenity has to be taken into account. We believe that the above two factors pull the two ends of the rope in the tug of war of the decision between drains or no drains. Since surgeons’ serenity seems to be largely influenced by the number of thyroidectomies performed, this is probably the reason why no drains are used in high volume specialized centers. However, as thyroidectomies are largely performed by general surgeons or otorinolaryngologists in general departments, this is the reason why drains are placed in a large proportion of thyroidectomised patients.

The results of this study confirm that the usage of drains when performing total thyroidectomy for a large goiter gives no advantage or disadvantage to the surgeon. Postoperative course and complication rates are comparable in both groups. The only “major” disadvantage that drains have is that they induce discomfort in the patient. On the other hand, they probably play an important role in the surgeons’ serenity, especially when the operation is performed in nonspecialized departments.

New energy sources and methods of hemostasis have been used in thyroid surgery with great effectiveness over the last years. However, the classic clamp-and-tie thyroidectomy has not been abandoned and is frequently employed in general surgery departments, either due to the unavailability of new technologies or a lack of training in other techniques.

The present study supports the fact that the incidence of major complications is not altered in any way by the usage of drains.

The results of this study confirm that the usage of drains when performing total thyroidectomy for a large goiter gives no advantage or disadvantage to the surgeon.

Drains in clamp-and-tie total thyroidectomy for large goiters give no advantage or disadvantage to the surgeon.

The authors have studied the potential benefits of drainage after total thyroidectomy in cases where no advanced hemostatic instruments were used.

P- Reviewers: Coskun A, Ha PK, Vaiman M S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Barczyński M, Konturek A, Cichoń S. Minimally invasive video-assisted thyreoidectomy (MIVAT) with and without use of harmonic scalpel--a randomized study. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393:647-654. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Papavramidis TS, Sapalidis K, Michalopoulos N, Triantafillopoulou K, Gkoutzamanis G, Kesisoglou I, Papavramidis ST. UltraCision harmonic scalpel versus clamp-and-tie total thyroidectomy: a clinical trial. Head Neck. 2010;32:723-727. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Andrieu G, Amrouni H, Robin E, Carnaille B, Wattier JM, Pattou F, Vallet B, Lebuffe G. Analgesic efficacy of bilateral superficial cervical plexus block administered before thyroid surgery under general anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:561-566. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 78] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Papavramidis TS, Michalopoulos N, Pliakos J, Triantafillopoulou K, Sapalidis K, Deligiannidis N, Kesisoglou I, Ntokmetzioglou I, Papavramidis ST. Minimally invasive video-assisted total thyroidectomy: an easy to learn technique for skillful surgeons. Head Neck. 2010;32:1370-1376. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Koulouris C, Papavramidis TS, Pliakos I, Michalopoulos N, Polyzonis M, Sapalidis K, Kesisoglou I, Gkoutzamanis G, Papavramidis ST. Intraoperative stimulation neuromonitoring versus intraoperative continuous electromyographic neuromonitoring in total thyroidectomy: identifying laryngeal complications. Am J Surg. 2012;204:49-53. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Kesisoglou I, Papavramidis TS, Michalopoulos N, Ioannidis K, Trikoupi A, Sapalidis K, Papavramidis ST. Superficial selective cervical plexus block following total thyroidectomy: a randomized trial. Head Neck. 2010;32:984-988. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Spanknebel K, Chabot JA, DiGiorgi M, Cheung K, Curty J, Allendorf J, LoGerfo P. Thyroidectomy using monitored local or conventional general anesthesia: an analysis of outpatient surgery, outcome and cost in 1,194 consecutive cases. World J Surg. 2006;30:813-824. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Debry C, Renou G, Fingerhut A. Drainage after thyroid surgery: a prospective randomized study. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113:49-51. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Peix JL, Teboul F, Feldman H, Massard JL. Drainage after thyroidectomy: a randomized clinical trial. Int Surg. 1992;77:122-124. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Ayyash K, Khammash M, Tibblin S. Drain vs. no drain in primary thyroid and parathyroid surgery. Eur J Surg. 1991;157:113-114. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Wihlborg O, Bergljung L, Mårtensson H. To drain or not to drain in thyroid surgery. A controlled clinical study. Arch Surg. 1988;123:40-41. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kristoffersson A, Sandzén B, Järhult J. Drainage in uncomplicated thyroid and parathyroid surgery. Br J Surg. 1986;73:121-122. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Schoretsanitis G, Melissas J, Sanidas E, Christodoulakis M, Vlachonikolis JG, Tsiftsis DD. Does draining the neck affect morbidity following thyroid surgery. Am Surg. 1998;64:778-780. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Shaha AR, Jaffe BM. Selective use of drains in thyroid surgery. J Surg Oncol. 1993;52:241-243. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ariyanayagam DC, Naraynsingh V, Busby D, Sieunarine K, Raju G, Jankey N. Thyroid surgery without drainage: 15 years of clinical experience. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1993;38:69-70. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Schwarz W, Willy C, Ndjee C. Gravity or suction drainage in thyroid surgery Control of efficacy with ultrasound determination of residual hematoma. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1996;381:337-342. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Khanna J, Mohil RS, Chintamani D, Mittal MK, Sahoo M, Mehrotra M. Is the routine drainage after surgery for thyroid necessary A prospective randomized clinical study [ISRCTN63623153]. BMC Surg. 2005;5:11. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 60] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hopkins B, Steward D. Outpatient thyroid surgery and the advances making it possible. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;17:95-99. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mirnezami R, Sahai A, Symes A, Jeddy T. Day-case and short-stay surgery: the future for thyroidectomy. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61:1216-1222. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Colak T, Akca T, Turkmenoglu O, Canbaz H, Ustunsoy B, Kanik A, Aydin S. Drainage after total thyroidectomy or lobectomy for benign thyroidal disorders. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2008;9:319-323. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Harding J, Sebag F, Sierra M, Palazzo FF, Henry JF. Thyroid surgery: postoperative hematoma--prevention and treatment. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2006;391:169-173. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 73] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Schwartz AE, Clark OH, Ituarte P, Lo Gerfo P. Therapeutic controversy: Thyroid surgery--the choice. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1097-1105. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Burkey SH, van Heerden JA, Thompson GB, Grant CS, Schleck CD, Farley DR. Reexploration for symptomatic hematomas after cervical exploration. Surgery. 2001;130:914-920. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 176] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Materazzi G, Dionigi G, Berti P, Rago R, Frustaci G, Docimo G, Puccini M, Miccoli P. One-day thyroid surgery: retrospective analysis of safety and patient satisfaction on a consecutive series of 1,571 cases over a three-year period. Eur Surg Res. 2007;39:182-188. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 77] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Marohn MR, LaCivita KA. Evaluation of total/near-total thyroidectomy in a short-stay hospitalization: safe and cost-effective. Surgery. 1995;118:943-947; discussion 947-948. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 64] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |