Published online Feb 10, 2014. doi: 10.5317/wjog.v3.i1.1

Revised: October 20, 2013

Accepted: December 9, 2013

Published online: February 10, 2014

Processing time: 215 Days and 10.8 Hours

The ‘‘Center of Excellence’’ concept has been employed in healthcare for several decades. This concept has been adopted in several disciplines; such as bariatric surgery, orthopedic surgery, diabetes and stroke. The most successful model in surgery thus far has been the bariatric program, with a very extensive network and a large prospective database. Recently, the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists has introduced this concept in gynecologic surgery. The ‘‘Center Of Excellence in Minimally Invasive Gynecology’’ (COEMIG) designation program has been introduced with the goals of increasing safety and efficiency, cutting cost and increasing patient awareness and access to minimally invasive surgical options for women. The program may harbor challenges as well, such as human and financial resources, and difficulties with implementation and maintenance of such designation. This commentary describes the COEMIG designation process, along with its potential benefits and possible challenges. Though no studies have been published to date on the value of this concept in the field of gynecologic surgery, we envision this commentary to provoke such studies to examine the relative value of this new program.

Core tip: There are a number of benefits and potential challenges inherent to the ‘‘Center Of Excellence in Minimally Invasive Gynecology’’ (COEMIG) program. With an understanding of these challenges, organizations pursuing COEMIG may find advantages in efficiency, marketing and growth for both the institution and practice as a whole. There may also be reductions in complications, improvement in patient satisfaction and potentially reductions in cost that can arise as a result of COEMIG.

- Citation: Moawad NS, Canning A. Centers of excellence in minimally invasive gynecology: Raising the bar for quality in women's health. World J Obstet Gynecol 2014; 3(1): 1-6

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6220/full/v3/i1/1.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5317/wjog.v3.i1.1

A program has recently been implemented whereby surgical facilities and gynecologic surgeons can earn the designation of ‘‘Center Of Excellence in Minimally Invasive Gynecology’’ (COEMIG). The COE programs are focused on improving the safety and quality of surgical care, and lowering the overall costs associated with successful treatment. They are designed to expand patient awareness of - and access to - surgical procedures performed by surgeons and facilities that have demonstrated excellence in the specialty-specific techniques[1]. Under the direction of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL) and administered by the Surgical Review Corporation (SRC), surgeons, hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers around the world that provide minimally invasive gynecologic surgical care may now pursue designation as a ‘‘Center of Excellence in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic’’[2]. Though the nomenclature and its application vary, centers of excellence have been shown to improve outcomes and reduce costs[3]. The implementation of strict guidelines including procedure volumes, complication rates, readmissions, and mortality has helped to refine what exactly constitutes a standard center of excellence[4]. Recently, the University of Florida minimally invasive gynecologic surgery program has been designated as a COEMIG site. Herein we attempt to provide a concise description of the COEMIG program, including both its potential benefits and challenges. In doing so, we hope to stimulate research pertaining to this relatively new and uninvestigated process.

COE concept dates back to the 1960s and generally describes a facility or organization which creates value that exceeds the norm in the locale of interest[3]. Similarly, the National Institutes of Health designate centers of excellence to institutes that have made concerted progress in a given area of research[5]. In the case of COEMIG and similar COE programs like that of bariatric surgery and cardiovascular service, COE refers to a specialty that works to incorporate the highest standards of practice into their entire scope of operations[6]. In the most fundamental sense of the term, a center of excellence should strive to fulfill several basic goals, including the presence of an integrated program, a comprehensive array of services, diverse ability to handle complications, high levels of patient satisfaction, a lower cost based on improved safety and efficiency, and a commitment to the continual measurement and comparison of care quality[7]. Our organization utilizes several methods for extracting patient satisfaction, including paper and electronic methods. Ideally, monitoring patient satisfaction scores and comparing data over time to the baseline scores before COEMIG designation may provide insight into the effect of the program on patient satisfaction.

The American Society for Bariatric Surgery (ASBS) recognized the need for this framework of care delivery and assessment in bariatric surgery and in 2003 they formed the nonprofit accreditation agency, surgical review corporation (SRC)[7]. The bariatric surgery center of excellence program has been shown to improve surgical outcomes[8]. This positive performance may be related in part to the fact that center of excellence programs are typically found in higher volume facilities (> 100 cases per year) with literature supporting volume as a metric by which accreditation occurs[9]. Compared to low volume facilities, patients who underwent gastric bypass at high-volume hospitals had a shorter length of hospital stay (3.8 d vs 5.1 d, P < 0.01), lower overall complications (10.2% vs 14.5%, P < 0.01), lower complications of medical care (7.8% vs 10.8%, P < 0.01), and lower costs ($10292 vs $13908, P < 0.01), further compounding this notion[10]. Additionally, centers of excellence in knee and hip replacement have also shown statistically significant lower risk of complications with an odds ratio of 0.80 (P = 0.002)[11].

The AAGL was inspired by the success of the bariatric and knee and hip center of excellence programs and partnered with SRC in 2010 to launch the COEMIG program. Like other center of excellence programs, COEMIG focuses on improving outcomes, reducing costs, increasing access to minimally invasive procedures and advancing the field.

The ten-year-old accreditation methodology used for the bariatric centers of excellence program has proven efficacious in improving surgical outcomes and lowering readmission rates[8,12]. COEMIG utilizes a similar system to promote a potentially transformative mechanism for surgeons, healthcare organizations and the discipline of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery as a whole[1]. SRC reports that this transformation includes processes to improve safety and efficacy, promote practice development, contain costs and improve patient satisfaction[1].

COEMIG adoption may also prove beneficial for the discipline of gynecologic surgery in general. For individual practices, SRC also asserts that through the effective marketing and communication of COEMIG status, healthcare organizations and surgeons may be able to use their position for personal and organizational benefit and likely impact contract negotiations, reimbursement rates and referral patterns[1].

SRC incorporates three committees, including boards for Standards, Review and Outcomes[13]. Each of these committees is comprised of a host of the industry’s leading surgeons, each working to monitor and ensure an alignment of missions between the AAGL and organizations seeking COEMIG status. As of the date of this publication, 75 institutions and 282 gynecologic surgeons have earned the COEMIG designation. An additional 6 institutions and 45 surgeons are in the final stages of being designated[14].

COEMIG works to foster excellence in the field through the establishment of a live outcomes database, much like the bariatric outcomes longitudinal database (BOLD) of the BSCOE program. The goal of this database is to help establish a standard resource of information for the accumulation and analysis of improvements or areas of need within the field. This large, prospective database will also enable the development of new “standards” of care through monitoring outcomes for issues that have long been debatable due to the lack of large prospective trials. The BOLD is now the world’s largest and most comprehensive repository of related clinical bariatric surgery patient information, a vital resource that the COEMIG database will likely try to emulate for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery[15].

COEMIG designation is promoted by the American Association of Gynecologic Laproscopists and the Surgical Review Corporation, through their website, e-mails, webinars, meetings, periodicals, journals and direct mail to the membership. Through the COEMIG initiative, the AAGL and SRC provide the opportunity to surgeons, practices, and hospitals of varying size and scope to pursue the designation and contribute to the potential growth and enhancement of the field.

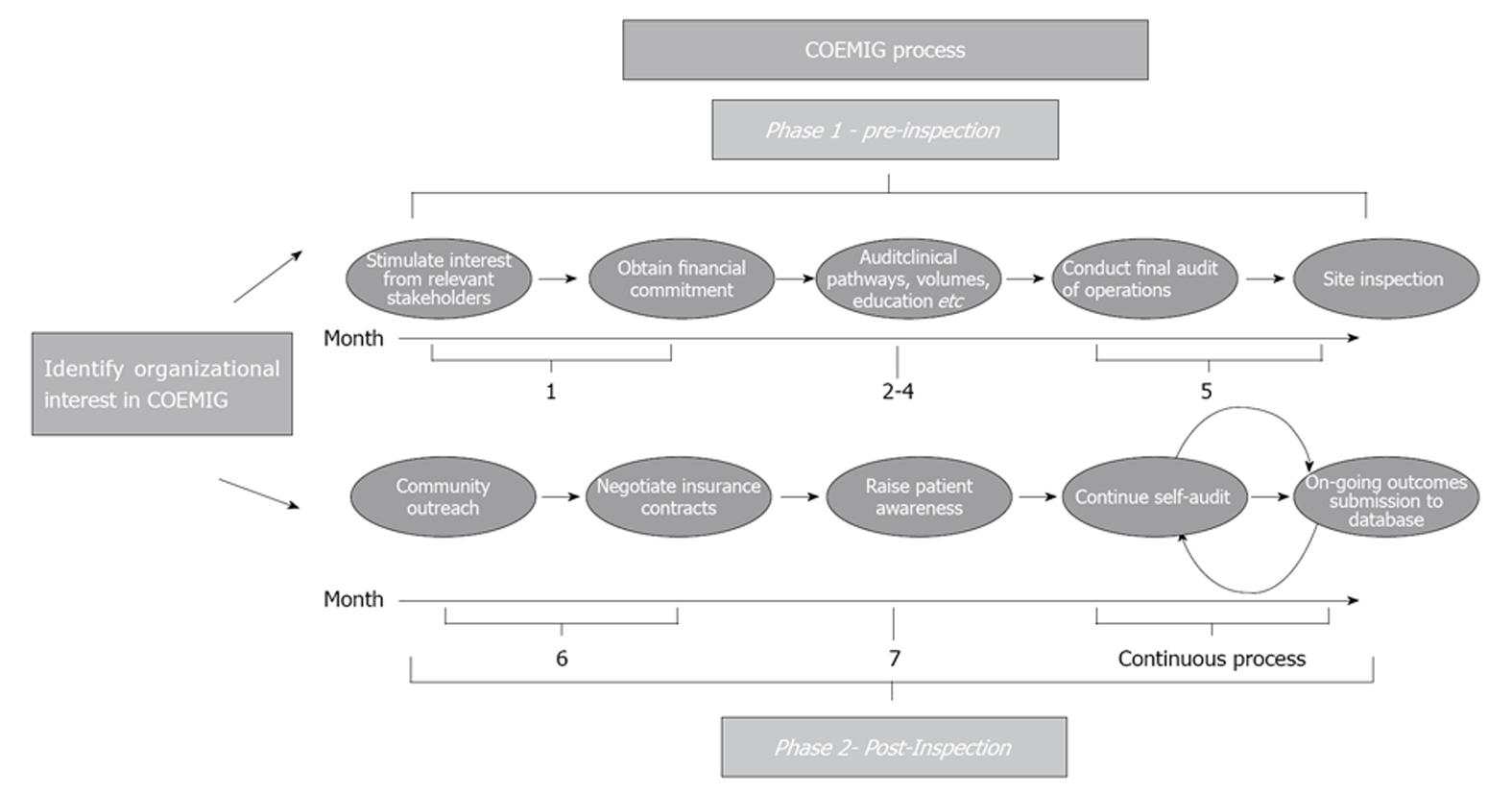

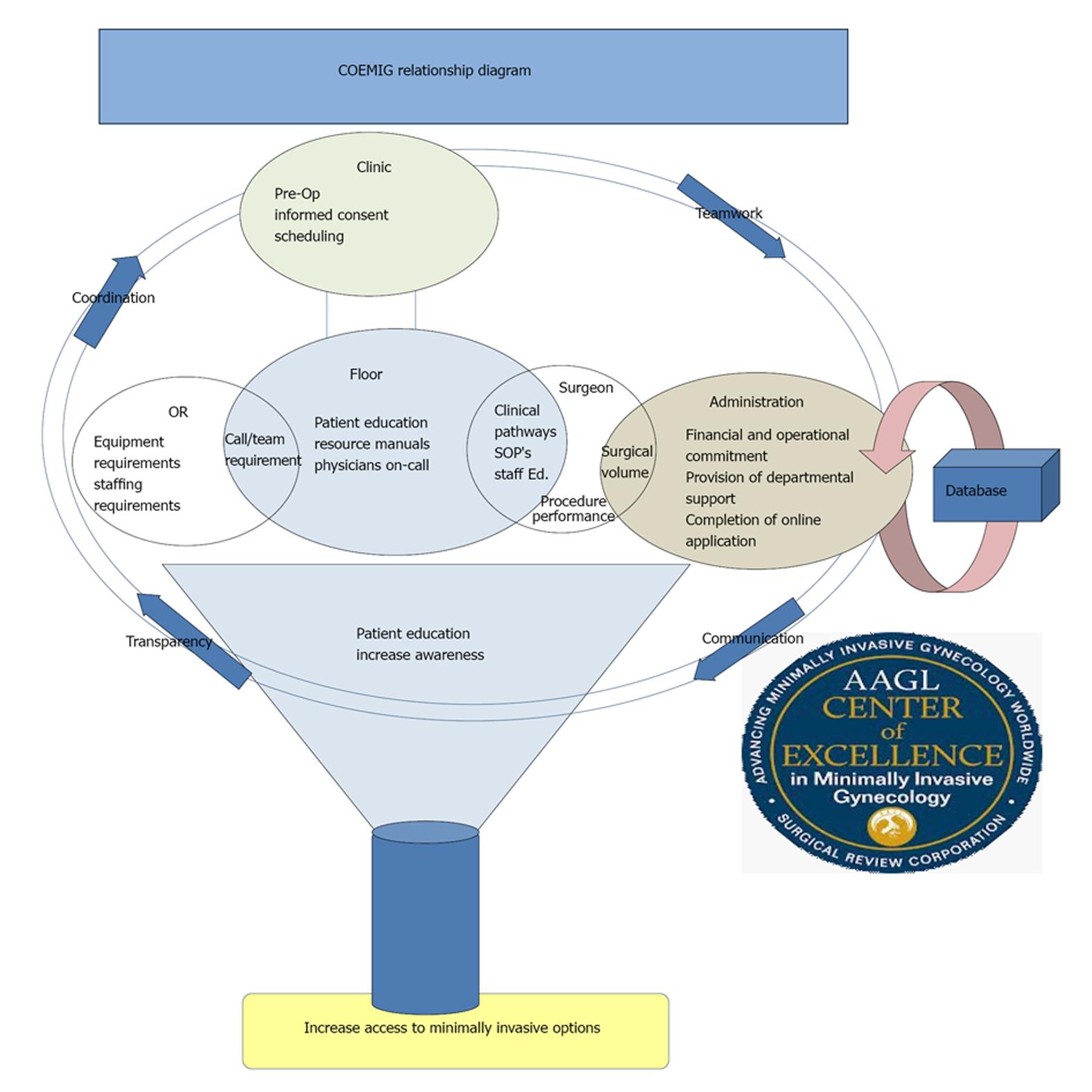

The University of Florida Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery (MIGS) program found it desirable to pursue designation, to strengthen the multidisciplinary team approach to the care of the minimally invasive surgical patient and to streamline our processes and procedures. The application process proved transformative for us and produced a level of organizational examination and introspection that have led to significant benefit. The process itself, outlined in Figure 1 was not a short one; a significant amount of effort and time was required for successful preparation and completion. In addition to workload, pursuit of COEMIG demanded a high level of consistent, clear communication among multiple units of the organization, displayed in Figure 2. Through an organized and focused approach, coupled with a fluid, communicative relationship among all involved, our pursuit of COEMIG was ultimately successful.

Certain aspects of the COEMIG application process in particular have encouraged a positive transformation in our practice. The augmentation of existing clinical pathways for example, has been an excellent method for analyzing organizational processes and ensuring their effectiveness, consistency and efficiency. Clinician and staff education requirements also provided an effective platform for bringing together the MIGS team and confirming and growing their knowledge base and synergy level. To maintain this synergy, quarterly staff education sessions on topics pertaining to minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, as well as in-services on equipment, are required for designation. Additionally, participating surgeons will need to maintain continued medical education credits in topics pertaining to minimally invasive surgery while also participating in staff education and quarterly team meetings.

Detailed review of volumes pointed out opportunities for improvement in coding and documentation, though formal percentages of error were not recorded. Some procedural volumes CPT codes provided by SRC were not congruent with the codes used within our organization. These challenges did not impact safety and efficiency; however they did add an additional layer of difficulty to the application process. The use of a prospective database will strive to alleviate this obstacle, as retrospective data collection will no longer be necessary. The creation of resource manuals for each unit that MIGS patients visit worked to ensure a consistent and reliable reference. Our resource manual includes call schedules, consultants, equipment specifications, patient education material, clinical pathways, standard operating procedures and consent information. Through the creation of these manuals, we were able to establish a more refined and identifiable source for information within our department.

The application process requires linked facility and surgeon(s) applications. Neither a surgeon nor a facility can apply independently. Hence, collaboration and building a unified goal between the facility and the applicant surgeon(s) are paramount. Surgeon requirements include demonstration of adequate surgical experience in laparoscopic and/or hysteroscopic procedures, a physician program director, qualified call coverage, consistent utilization of clinical pathways and standard operating procedures, informed patient decision making and consents for procedures commonly performed, and continuous assessment of quality goals[16]. The facility requirements include an institutional commitment to excellence in minimally invasive gynecology, surgical experience and volumes, a physician program director leading a multidisciplinary team, surgeons and qualified call coverage, and 24/7 consultant availability, advanced equipment and instruments, clinical pathways and standard operating procedures. Additional requirements include consistent, trained surgical team and support staff, documentation of informed patient decision making and consent and continuous assessment of quality and safety goals, defined by operative time, estimated blood loss, rate of complications, length of stay, reoperations, readmissions and mortality[17]. Specific difficulties in addressing these requirements within our organization dealt with the scope of the institution and the intricate navigation that occurs while trying to collect information and resources in a relatively short period of time. We found it beneficial and efficient to ensure brief but focused communication sessions at regularly scheduled intervals between a close group of relevant parties for the delegation and assurance of timely duty completion.

COEMIG requirements embrace similar criteria to other quality programs such as the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO). Staff education requirements and physician CME requirements foster the environment of safety that is promoted by other quality programs. It is important to note that an additional program is available in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and is administered through the American Institute of Minimally Invasive Surgery (AIMIS). The requirements of this program are parallel to those of COEMIG. Individual institutions and surgeons can choose the program that fits their style or environment. The programs should be viewed as complimentary rather than competitive, with the overarching motivation to improve safety in a larger number of institutions and improve patient access to minimally invasive surgical procedures in institutions and by surgeons that have met minimum criteria for designation.

Additional surgeons in our organization began seeking COEMIG designation within 5 mo, interested in the potential benefits of our pursuit of designation as a center of excellence. Although all of the surgeons within an organization may not initially choose to pursue COEMIG, this is not a reflection of their quality of practice. Moreover, the overarching benefits to the entire institution help improve the organization as a whole and may stimulate other surgeons’ interest in meeting the criteria to be designated. We envision this designation to incrementally increase volume, safety and efficiency of our processes and increase patient awareness and access to minimally invasive surgical options, and consequently, improve patient outcomes and satisfaction. Though a formal definition has not been implemented, efficiency will be monitored and measured through the recording of operative times, length of stay and complications. Each of these metrics coordinates directly with the cost of care and monitoring these changes over time may reflect changes in the level of efficient operation within a COEMIG applicant institution. These benefits illustrate a potentially positive transformational process within one organization, but the overarching implications of these changes may be considered for the practice of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery as a whole.

The execution of the center of excellence designation process does possess challenges and potential pitfalls. While physicians may foresee the possible benefits of creating a center of excellence, aligning the goals with hospital leadership may prove more challenging. A financial commitment is required for participation in the program, as with many other designation processes. The required fees include a COEMIG application fee of $7500, COEMIG surgeon application fee of $650 and site Inspection fee of $1850. Annual COEMIG institution participation fee of $3975 and an annual COEMIG surgeon participation fee of $650 are required. There are also significant effort, staffing and time commitments involved in the process. Staff education, standardized clinical pathways and operating procedures are some of the core requirements that can demand time, effort and consensus-building among participating surgeons. Another designation requirement is commitment to submit all surgical data into a prospective database, a task that will require ongoing support and accuracy, with potential added cost. It is conceivable that COEMIG pursuit may harbor personal interests and pose ethical issues; however, COEMIG designation is available to any facility that meets the requirements, including small and large practices, community and academic institutions as well as outpatient surgery centers[18].

COEMIG designation will vary based on the institution’s size and practice type. In larger institutions, the disparate locations and motivations of departments and key stakeholders may make it challenging for the completion of certain aspects of the application. Conversely, smaller organizations may reach consensus easier, but may find it challenging to demonstrate adequate volume and to make the financial and personnel commitments required to achieve COEMIG designation. COEMIG applicants may also see a challenge in gaining interest from non-applicant surgeons; however, it is important to maintain that this does not mean those surgeons are not “excellent” in practice. It may be beneficial for organizations and the center’s leadership to ensure that this fact is communicated to its surgeons so as not to create an exclusionary environment within their facility. Another foreseeable pitfall of designation is potentially misleading the patients to believe that every practicing surgeon in the facility is COEMIG-designated, while this is not true in most institutions. The Surgical Review Corporation has developed safeguards against this in the institutional agreements. Marketing of COEMIG will be important to the impact of its implementation. However, surgeons and organizational leaders must remain focused on the core purpose of COEMIG, which is to examine and improve the operations of an institution and ultimately improve patient care.

COEMIG designation remains in effect as long as the center is in good standing and verifiable compliance with all current requirements and program criteria, monitored every three years as part of a renewal cycle. At the three-year re-inspection visit, or sooner through monitoring the prospective database, surgeons who are not meeting the criteria will be moved back to a provisional status. Provisional status prohibits the surgeon from communicating his/her COEMIG designation in any fashion. If the surgeon is able to rectify the deficiency, she/he is moved back to the designated status. Conversely, if the deficiency is not rectified, the surgeon will lose his or her designation and is required to reapply in the future if she/he so desires. It is imperative for institutions interested in COEMIG to weigh the challenges and benefits when deciding whether this pursuit is appropriate for their organization.

It is important that COE programs make every effort to be inclusive, so that to build partnership with every institution and individual surgeon that can provide consistent, safe and efficacious minimally invasive surgical options for women. The driving purpose for this is to increase awareness and access to patients, and encourage the increased training of surgeons and staff and utilization of minimally invasive approaches. By elevating the level of practice, sharpening the operations of individual organizations and establishing an ongoing outcomes database for review and analysis, the COEMIG process generates a possible platform for advancing an entire arena of practice. The value of a large, prospective national and international database cannot be underestimated, not only for clinical research and advancing the field, but also for monitoring surgeons’ and hospitals’ progress over time and for anonymous comparison to peer surgeons and institutions. Though the COEMIG process is not without challenges, this incarnation of quality will and should serve to augment organizations, the field and most importantly, the standard of patient care.

P- Reviewers: Coccolini F, Nasu K, Sonoda K S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Surgical Review Corporation. COEMIG Benefits. Available from: http: //www.surgicalreview.org/coemig/benefits/. |

| 2. | Worcester S. AAGL creates COEMIG to improve outcomes. OB GYN News. 2012;47:1. |

| 3. | Wess BP. Defining “centers of excellence”. Health Manag Technol. 1999;20:28-30. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Witt FJ. Hospital centers of excellence defy geographic trends. Physician Exec. 2012;38:16-20. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Stewart-Amidei C. Centers of excellence: getting on the bandwagon. J Neurosci Nurs. 2007;39:195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zuckerman AM, Markham CH. Centers of excellence: big opportunities, big dividends. Healthc Financ Manage. 2006;60:150, 152, 154. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Pories WJ. Surgical Review Corporation: Centers of excellence. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2005;1:60-61. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shikora SA, Wolfe B, Schirmer B. Bariatric centers of excellence programs do improve surgical outcomes. Arch Surg. 2010;145:105-106. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Hollenbeak CS, Rogers AM, Barrus B, Wadiwala I, Cooney RN. Surgical volume impacts bariatric surgery mortality: a case for centers of excellence. Surgery. 2008;144:736-743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nguyen NT, Paya M, Stevens CM, Mavandadi S, Zainabadi K, Wilson SE. The relationship between hospital volume and outcome in bariatric surgery at academic medical centers. Ann Surg. 2004;240:586-593; discussion 593-594. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Mehrota A, Sloss EM, Hussey PS, Adams JL, Lovejoy S, Soohoo NF. Evaluation of centers of excellence program for knee and hip replacement. Med Care. 2012;51:1. |

| 12. | Bradley DW, Sharma BK. Centers of Excellence in Bariatric Surgery: design, implementation, and one-year outcomes. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:513-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Surgical Review Corporation. COEMIG Program leadership. Available from: http: //www.surgicalreview.org/coemig/leadership. |

| 15. | Surgical Review Corporation. News Releases World’s Largest Bariatric Surgery Database Reaches 250,000 Patients. Available from: http: //www.surgicalreview.org/news/2010/05/bold-250k. |

| 16. | Surgical Review Corporation. COEMIG Designation Requirements. Available from: http: //www.surgicalreview.org/coemig/requirements. |

| 17. | Kohn GP, Galanko JA, Overby DW, Farrell TM. High case volumes and surgical fellowships are associated with improved outcomes for bariatric surgery patients: a justification of current credentialing initiatives for practice and training. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Badlani N, Boden S, Phillips F. Orthopedic specialty hospitals: centers of excellence or greed machines? Orthopedics. 2012;35:e420-e425. [PubMed] |