Published online Nov 10, 2013. doi: 10.5317/wjog.v2.i4.101

Revised: March 28, 2013

Accepted: May 8, 2013

Published online: November 10, 2013

Processing time: 339 Days and 5.5 Hours

In this descriptive review we look at the role of surgery for advanced ovarian cancer at other timepoints apart from the initial cytoreduction for front-line therapy or interval cytoreductive surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The chief surgical problem to face after primary treatment is recurrent ovarian cancer. Of far more marginal concern are the second-look surgical procedures or the palliative efforts intended to resolve the patient’s symptoms with no curative intent. The role of surgery in recurrent ovarian cancer remains poorly defined. Current data, albeit from non-randomized studies, nevertheless clearly support surgical cytoreduction in selected patients, a rarely curative expedient that invariably yields a marked survival advantage over chemotherapy alone. Despite these findings, some consider it too early to adopt secondary cytoreduction as the standard care for patients with recurrent ovarian cancer and a randomized study is needed. Two ongoing randomized trials (Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynäkologische Onkologie-Desktop III and Gynecologic Oncology Group 213) intend to verify the role of secondary cytoreduction for platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer compared with chemotherapy considered as standard care for these patients. We await the results of these two trials for a definitive answer to the matter.

Core tip: The chief surgical problem to face after primary treatment is recurrent ovarian cancer. The role of surgery in recurrent ovarian cancer remains poorly defined. Current data, albeit from non-randomized studies, nevertheless clearly support surgical cytoreduction in selected patients, a rarely curative expedient that invariably yields a marked survival advantage over chemotherapy alone. Despite these findings, some consider it too early to adopt secondary cytoreduction as the standard care for patients with recurrent ovarian cancer and a randomized study is needed.

- Citation: Sammartino P, Cornali T, Malatesta MFD, Piso P. Cytoreductive surgery after recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer and at other timepoints. World J Obstet Gynecol 2013; 2(4): 101-107

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6220/full/v2/i4/101.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5317/wjog.v2.i4.101

Recurrent disease is a challenging problem that sooner or later (within 18 mo after primary treatment) arises in about 80% of patients initially treated for advanced ovarian cancer[1-3] and contributes substantially to the poor long-term outcome for this disease portending long-term survival in only 20%-30% of patients already at an advanced stage when diagnosed[4,5].

Before considering the current options for treating patients with recurrent ovarian cancer we therefore deem it useful to analyze the possible reasons explaining why the disease recurs.

The natural history of ovarian epithelial malignancies shows that tumors originating from the epithelium lining the ovarian surface, and according to the most recent cytogenic hypotheses also those arising from the epithelium covering the fallopian tubes and fimbria[6,7], spread early to the peritoneum and locoregional lymph nodes[8].

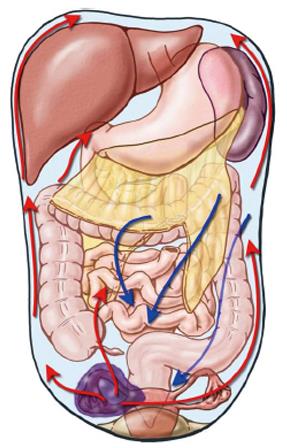

Peritoneal spread, frequently with ascites, follows a well-known anatomic course linked to peritoneal fluid dynamics leading neoplastic cells to colonize distant pelvic areas early thus making ovarian carcinoma the model for peritoneal spread from an intra-abdominal malignancy (Figure 1)[9,10].

These pathophysiological events easily explain epidemiological data showing that when the disease is first diagnosed about 75% of women already have advanced ovarian cancer [International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) III-IV][8] with major peritoneal and lymphatic spread obviously making the whole therapeutic strategy a complex task.

Although surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy remain the mainstay of treatment for advanced ovarian cancer the optimal therapeutic goal remains hard to reach[11]. Even though the specific single therapeutic role that each of the two principle procedures (surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy) covers in integrated treatment is difficult to investigate, we underline that the outcome benefits induced by platinum and its derivatives and paclitaxel (eventually given also by the intraperitoneal route) have presumably reached a plateau that appears arduous to improve until new effective anticancer drugs become available[12].

Even though experience over years has recognized the prognostic importance of surgical cytoreduction (less residual disease = better outcome)[13], a concept underlined in a meta-analysis conducted in recent years by Bristow et al[14], surgery remains the most highly variable and poorly standardized therapeutic factor, depending on the various surgical schools, the individual surgeon’s cancer treatment policy and aims and finally on their technical skills.

Besides, some clinical oncologists, questioning whether surgery is really curative, despite convincing clinical evidence, hypothesize that whenever surgery achieves optimal disease control biological factors come into play and exert a determinant influence on the surgical outcome[15]. Going beyond these hypotheses if we want focus on the therapeutic potential of surgery in advanced ovarian cancer we have to analyze precisely what these surgical procedures aim to achieve and most important, how they are classified.

The surgical procedure for treating ovarian cancer is defined with the term “cytoreduction”, a definition that seemingly implies residual disease after surgical debulking. Indeed, published studies invariably express their surgical results in terms of residual disease, using classifications that may overlap over time but nevertheless identify as “optimal cytoreduction” surgery leaving residual disease measuring 2 to 1 cm or less. In the latest Cochrane systematic review on this topic[11] the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) currently defines optimal cytoreduction as residual tumor nodules “each” measuring 1 cm or less in maximal diameter underlining, however, the ideal surgical outcome as complete cytoreduction with no visible residual disease. The same review, analyzing experience gained in the most accredited world centers or most cited studies, underlines that surgery achieves this ideal outcome in only a mean 28% of the patients treated and most published surgical results describe residual disease ranging from less than 1 cm to more than 2 cm. Equally important, published surgical reports fail to quantify the overall number of residual lesions in each patient. Yet for two patients at the same disease stage both classified as optimally cytoreduced (residual disease measuring less than 1 cm) if one patient has 10 sites of residual disease and the other, for example, has more than 100 residua, outcomes can presumably differ. Similarly, in classification systems other than those used by the GOG (completeness of cytoreduction score, by Sugarbaker[16]) the lack of a variable quantifying the overall number of residual lesions creates substantial bias in analyzing the results because the group classified as optimally cytoreduced could comprise patients with differing amounts of residual disease. This drawback, already noted previously[17] but never investigated further, merits study to decide how to analyze the results in a more meaningful manner. Hence we reasonably presume that other clinical conditions (age, stage, performance status, platinum sensitivity, body surface area and therefore pharmacological dose) being equal, in two optimally cytoreduced patients in whom the number of residual lesions differs widely adjuvant chemotherapy will yield non-overlapping results.

All these observations prompt us to suggest that recurrent disease in advanced ovarian cancer should in many patients be more correctly interpreted as residual disease given that despite adjuvant chemotherapy surgery often leaves numerically rather than diametrically important residual lesions that ultimately manifest clinically as recurrence.

This term defines the surgical procedure used to confirm the response status in patients who are clinically disease-free after a front-line approach (primary cytoreduction and adjuvant chemotherapy). Second-look surgery is obviously not intended merely as a diagnostic procedure given that it envisages whenever possible resecting all clinically unrecognized disease eventually found.

The rationale underlying second-look surgery originally hinged on the concept that identifying residual disease foci early after front-line chemotherapy, removing them and consolidating the results with second-line chemotherapy improved survival. Positive histologic findings after second-look surgery directly reflect the initial disease stage and their percentage increases further in patients whose first operation leaves macroscopic residual disease[18]. Although second-look surgical procedures enjoyed wide use in the 1980s and 1990s their application gradually declined insofar as more than 50% of the patients identified at second-look surgery as complete responders within 12 to 24 mo thereafter went on to experience recurrent disease[19,20]. Randomized clinical trials have shown that although second-look procedures can accurately define patient responders they failed to increase survival[21]. An Italian study intended to investigate whether during a second-look procedure systematic aortic and pelvic lymphadenectomy had outcome advantages over a simple biopsy taken from clinically suspected lymph-node stations failed to show that either procedure improved outcome[22].

In synthesis, current evidence therefore suggests that second-look surgery for ovarian cancer remains a useful therapeutic option when diagnostic investigations appear contrasting and can help ascertain the patient’s clinical status and eventually treat the disease but should be reserved for individual patients and has no place as a general procedure. However, it may be a valid option for patients whom are detected during second-look surgery with platinum-resistant recurrent disease. If a complete macroscopic cytoreduction can be performed, patients will benefit as otherwise no real treatment options are available, in particular if hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) can be added to the concept.

Within 6 mo after undergoing treatment with the front-line approach (cytoreductive surgery plus primary adjuvant chemotherapy) 23% of patients with advanced ovarian cancer experience recurrent disease[23,24]. Current consensus defines these patients as platinum-resistant. Platinum-resistance is a highly complex phenomenon that can develop during the natural history of the disease after initial platinum sensitivity. Studies conducted over recent years have emphasized the role played in chemoresistance by the so-called cancerous ovarian stem cells[25]. Previous surgery and chemotherapy in platinum-resistant patients seem to provide exceedingly disappointing results with a median survival of less than 10 mo[26-29]. This concern has now stimulated research efforts thus moving basic research into pharmacologic regimens towards promising advances using biological agents alone or combined with chemotherapy agents[30-32].

From the viewpoint of the surgical approach, an extremely interesting new development seems to be the cumulative experience from two French groups who report in a large series of patients with recurrent ovarian cancer the surgical outcome after cytoreduction (peritonectomy procedures) and HIPEC and noted similar results in patients classified as platinum-sensitive and platinum-resistant[33]. These results seemingly underline the dual importance of endoperitoneal chemotherapy and concurrent hyperthermia. Endoperitoneal infusion undoubtedly has a pharmacokinetic advantage given that the “peritoneal plasma barrier” allows dose-intensity therapy and hyperthermia concurrently increases the chemotherapy agent’s cytotoxic action and cell penetration perhaps overcoming problems related to platinum resistance[34,35]. If further confirmed these findings open the way to interesting future therapeutic advances, in particular because the mortality related to the procedure including HIPEC is low after absolving the learning curve although relevant morbidity is still frequent but most of it seems to be related to extended surgery. However, in HIPEC performed with oxaliplatin, postoperative bleeding after 7-10 d following surgery can be a serious complication in up to one third of all patients requiering a reoperation[36].

The 4th ovarian cancer consensus conference held in 2010 stated that surgery might be appropriate in selected patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer and might be beneficial if it achieved complete resection[24]. The therapeutic value of repeating the initial surgical treatment (cytoreduction) in patients with advanced ovarian cancer who will experience tumor recurrence remains debatable. Since Berek et al[37] in 1983 first introduced the term “secondary cytoreduction” many papers published over the ensuing years have addressed this topic[38-44] and in recent years some investigators have even introduced the concept tertiary cytoreduction[45,46]. Secondary cytoreduction after an extended treatment-free interval (from 6 to 12 mo or more) can increase survival (though rarely leads to a definitive cure) because the cytoreductive effect sums up with an improved response to subsequent chemotherapy[47]. But beyond single series, the potential usefulness of secondary cytoreduction after primary treatment remains controversial: most studies are retrospective, come from single centers, often enrol fewer than 100 cases, cover a long time-span and most important, are non randomized[48]. To address these doubts Bristow et al[47] conducted a meta-analysis investigating the prognostic importance of several variables on overall survival in 40 patient cohorts (2019 cases) undergoing secondary cytoreduction for platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer. They used simple and multiple regression analyses, with weighted correlation calculations and after controlling for all other factors, each 10% increase in the proportion of patients undergoing complete cytoreductive surgery was associated with a 3.0 mo increase in median cohort survival time. The investigators concluded that among patients undergoing surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer, the proportion of patients achieving complete cytoreductive surgery is independently associated with overall post-recurrence survival time. The same study showed that other more strictly surgery-related variables such as operative time, blood loss, surgical morbidity and mortality were comparable with the data generally reported for primary cytoreduction, coming within an acceptable percentage of risk.

Yet given that outcome improves only in patients in whom surgery achieves complete cytoreduction, an inherent limitation in their meta-analysis, as Bristow et al[47] themselves admit, is the inability to define a correct profile for patients in whom they can achieve this aim and for whom we should reserve the surgical option. Two studies in recent years seem to answer this question by developing a risk model for predicting complete secondary cytoreductive surgery in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer. The Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynäkologische Onkologie (AGO) Desktop I study[40] evaluated three predictive factors for complete resection: good performance status (ECOG 0), complete resection at first surgery, absence of ascites and in the subsequent AGO-Desktop II study[49] this score was validated prospectively: if all three factors are present complete resection is feasible in 76% of the patients. A second risk model was developed in 1075 patients by an International Collaborative Cohort study[50,51] that partly integrated the previous model by evaluating the progression-free interval, the Ca 125 level and the FIGO stage. From these overall data they extrapolated two categories, patients at low risk (score ≤ 4.7) in whom complete cytoreduction is possible in 53% to 83% of the cases and those at high risk (score > 4.7) in whom surgery can achieve complete cytoreduction in from 20% to 42% (Table 1).

| Impact factors | Scoring | |||||

| 0 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 3 | |

| FIGO stage | I/II | III/IV | ||||

| Residual disease at 1st surgery | 0 | > 0 | ||||

| Progression-free interval (mo) | > 16 | < 16 | ||||

| ECOG performance status | 0-1 | 2-3 | ||||

| Ca 125 at recurrence (U/mL) | < 105 | > 105 | ||||

| Ascites at recurrence | Absent | Present | ||||

Despite these findings, some consider it too early to adopt secondary cytoreduction as the standard care for patients with recurrent ovarian cancer and a randomized study is needed[52]. Two ongoing randomized trials (AGO-Desktop III and GOG 213) intend to verify the role of secondary cytoreduction for platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer compared with chemotherapy considered as standard care for these patients. We await the results of these two trials for a definitive answer to the matter.

For patients following complete cytoreduction, HIPEC may be beneficial as suggested by a recent paper from France[33]. In the largest HIPEC series for persistent and recurrent ovarian cancer, including 246 patients, the median survival following surgical cytoreduction and HIPEC was 48.9 mo. Mortality was in this group very low with 0.37% and morbidity of 11.6%.

For platinum-sensitive recurrent disease, two other European prospective randomized trials are investigating at present the role of HIPEC. One trial is the French trial CHIPOR study: all patients get first neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy and surgical cytoreduction. Following surgery, patients are randomized to HIPEC (cisplatinum 75 mg/m2) vs no HIPEC. The other trial is the Italian trial HORSE with a similar design, however, without neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy and the same cisplatinum dose as in the French trial[53].

In conclusion, although surgical techniques and chemotherapy regimens used to treat ovarian cancer have advanced remarkably over the past several decades, despite the best efforts the 5-year survival rate has improved by only 8% since 1975[54].

The proportion of patients with advanced ovarian cancer who relapse has remained high and fairly constant and because cure is rarely possible, key objectives are to maintain and improve quality of life and prolong survival. Patients commonly undergo multiple chemotherapy courses[55] intended to overcome the platinum resistance that follows initial platinum sensitivity, control symptoms and allow disease chronification.

The role of surgery in recurrent ovarian cancer remains poorly defined. Current data, albeit from non-randomized studies, nevertheless clearly support surgical cytoreduction in selected patients, a rarely curative expedient that invariably yields a marked survival advantage over chemotherapy alone[50,56].

Although we realize that scientific research requires level 1 evidence to conclude that one therapeutic option is better than another, randomizing a patient with recurrent ovarian cancer who is technically operable (the Desktop III protocol requires as an inclusion criterion scores known to predict complete cytoreduction) could raise ethical doubts and probably does nothing to help patient accrual.

And finally, the latest advances from studies investigating the pathogenesis of ovarian cancer clearly show that a “blanket approach” to ovarian cancer treatment is insufficient[7]. The key future turning point for guaranteeing effective treatment depends on developing target therapies designed to exploit the molecular and genetic characteristics of individual tumor subtypes. These observations raise further doubts on the appropriateness of randomized trials enrolling patients whose tumors differ widely in biological features.

P- Reviewer: Diaz-Montes TP S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zheng XM

| 1. | Hennessy BT, Coleman RL, Markman M. Ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2009;374:1371-1382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 491] [Cited by in RCA: 518] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ledermann JA, Raja FA. Clinical trials and decision-making strategies for optimal treatment of relapsed ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47 Suppl 3:S104-S115. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Harter P, Heitz F, du Bois A. Surgery for relapsed ovarian cancer: when should it be offered? Curr Oncol Rep. 2012;14:539-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Armstrong DK, Bundy B, Wenzel L, Huang HQ, Baergen R, Lele S, Copeland LJ, Walker JL, Burger RA. Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:34-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2030] [Cited by in RCA: 1949] [Article Influence: 102.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ozols RF, Bundy BN, Greer BE, Fowler JM, Clarke-Pearson D, Burger RA, Mannel RS, DeGeest K, Hartenbach EM, Baergen R. Phase III trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel compared with cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with optimally resected stage III ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3194-3200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1618] [Cited by in RCA: 1518] [Article Influence: 69.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kurman RJ, Shih IeM. Pathogenesis of ovarian cancer: lessons from morphology and molecular biology and their clinical implications. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008;27:151-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Karst AM, Drapkin R. Ovarian cancer pathogenesis: a model in evolution. J Oncol. 2010;2010:932371. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Fader AN, Rose PG. Role of surgery in ovarian carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2873-2883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Carmignani CP, Sugarbaker TA, Bromley CM, Sugarbaker PH. Intraperitoneal cancer dissemination: mechanisms of the patterns of spread. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22:465-472. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Feki A, Berardi P, Bellingan G, Major A, Krause KH, Petignat P, Zehra R, Pervaiz S, Irminger-Finger I. Dissemination of intraperitoneal ovarian cancer: Discussion of mechanisms and demonstration of lymphatic spreading in ovarian cancer model. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2009;72:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Elattar A, Bryant A, Winter-Roach BA, Hatem M, Naik R. Optimal primary surgical treatment for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;CD007565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hoskins P, Vergote I, Cervantes A, Tu D, Stuart G, Zola P, Poveda A, Provencher D, Katsaros D, Ojeda B. Advanced ovarian cancer: phase III randomized study of sequential cisplatin-topotecan and carboplatin-paclitaxel vs carboplatin-paclitaxel. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:1547-1556. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Griffiths CT. Surgical resection of tumor bulk in the primary treatment of ovarian carcinoma. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1975;42:101-104. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Bristow RE, Tomacruz RS, Armstrong DK, Trimble EL, Montz FJ. Survival effect of maximal cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian carcinoma during the platinum era: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1248-1259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 804] [Cited by in RCA: 702] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Crawford SC, Vasey PA, Paul J, Hay A, Davis JA, Kaye SB. Does aggressive surgery only benefit patients with less advanced ovarian cancer? Results from an international comparison within the SCOTROC-1 Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8802-8811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sugarbaker PH. Peritoneal carcinomatosis: principle of management. Boston: Kluwer Academic 1996; . |

| 17. | Stoeckle E, Paravis P, Floquet A, Thomas L, Tunon de Lara C, Bussières E, Macgrogan G, Picot V, Avril A. Number of residual nodules, better than size, defines optimal surgery in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14:779-787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ayhan A, Yarali H, Develioğlu O, Uren A, Ozyilmaz F. Prognosticators of second-look laparotomy findings in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1991;46:222-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Podratz KC, Cliby WA. Second-look surgery in the management of epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;55:S128-S133. [PubMed] |

| 20. | NIH consensus conference. Ovarian cancer. Screening, treatment, and follow-up. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Ovarian Cancer. JAMA. 1995;273:491-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 328] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Nicoletto MO, Tumolo S, Talamini R, Salvagno L, Franceschi S, Visonà E, Marin G, Angelini F, Brigato G, Scarabelli C. Surgical second look in ovarian cancer: a randomized study in patients with laparoscopic complete remission--a Northeastern Oncology Cooperative Group-Ovarian Cancer Cooperative Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:994-999. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Dell’ Anna T, Signorelli M, Benedetti-Panici P, Maggioni A, Fossati R, Fruscio R, Milani R, Bocciolone L, Buda A, Mangioni C. Systematic lymphadenectomy in ovarian cancer at second-look surgery: a randomised clinical trial. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:785-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | du Bois A, Reuss A, Pujade-Lauraine E, Harter P, Ray-Coquard I, Pfisterer J. Role of surgical outcome as prognostic factor in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a combined exploratory analysis of 3 prospectively randomized phase 3 multicenter trials: by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie Studiengruppe Ovarialkarzinom (AGO-OVAR) and the Groupe d’Investigateurs Nationaux Pour les Etudes des Cancers de l’Ovaire (GINECO). Cancer. 2009;115:1234-1244. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Friedlander M, Trimble E, Tinker A, Alberts D, Avall-Lundqvist E, Brady M, Harter P, Pignata S, Pujade-Lauraine E, Sehouli J. Clinical trials in recurrent ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21:771-775. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Ahmed N, Abubaker K, Findlay J, Quinn M. Cancerous ovarian stem cells: obscure targets for therapy but relevant to chemoresistance. J Cell Biochem. 2013;114:21-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sehouli J, Stengel D, Harter P, Kurzeder C, Belau A, Bogenrieder T, Markmann S, Mahner S, Mueller L, Lorenz R. Topotecan Weekly Versus Conventional 5-Day Schedule in Patients With Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer: a randomized multicenter phase II trial of the North-Eastern German Society of Gynecological Oncology Ovarian Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:242-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Baumann K, Pfisterer J, Wimberger P, Burchardi N, Kurzeder C, du Bois A, Loibl S, Sehouli J, Huober J, Schmalfeldt B. Intraperitoneal treatment with the trifunctional bispecific antibody Catumaxomab in patients with platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian cancer: a phase IIa study of the AGO Study Group. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123:27-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Morris M, Gershenson DM, Wharton JT, Copeland LJ, Edwards CL, Stringer CA. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1989;34:334-338. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Segna RA, Dottino PR, Mandeli JP, Konsker K, Cohen CJ. Secondary cytoreduction for ovarian cancer following cisplatin therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:434-439. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Marchini S, Fruscio R, Clivio L, Beltrame L, Porcu L, Nerini IF, Cavalieri D, Chiorino G, Cattoretti G, Mangioni C. Resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy is associated with epithelial to mesenchymal transition in epithelial ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:520-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Verschraegen CF, Czok S, Muller CY, Boyd L, Lee SJ, Rutledge T, Blank S, Pothuri B, Eberhardt S, Muggia F. Phase II study of bevacizumab with liposomal doxorubicin for patients with platinum- and taxane-resistant ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:3104-3110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Heitz F, Harter P, Barinoff J, Beutel B, Kannisto P, Grabowski JP, Heitz J, Kurzeder C, du Bois A. Bevacizumab in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Adv Ther. 2012;29:723-735. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Bakrin N, Cotte E, Golfier F, Gilly FN, Freyer G, Helm W, Glehen O, Bereder JM. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for persistent and recurrent advanced ovarian carcinoma: a multicenter, prospective study of 246 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:4052-4058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | CRILE G. The effects of heat and radiation on cancers implanted on the feet of mice. Cancer Res. 1963;23:372-380. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Barlogie B, Corry PM, Drewinko B. In vitro thermochemotherapy of human colon cancer cells with cis-dichlorodiammineplatinum(II) and mitomycin C. Cancer Res. 1980;40:1165-1168. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Halkia E, Spiliotis J, Sugarbaker P. Diagnosis and management of peritoneal metastases from ovarian cancer. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:541842. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Berek JS, Hacker NF, Lagasse LD, Nieberg RK, Elashoff RM. Survival of patients following secondary cytoreductive surgery in ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1983;61:189-193. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Eisenkop SM, Friedman RL, Spirtos NM. The role of secondary cytoreductive surgery in the treatment of patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;88:144-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Zang RY, Li ZT, Tang J, Cheng X, Cai SM, Zhang ZY, Teng NN. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for patients with relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma: who benefits? Cancer. 2004;100:1152-1161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Harter P, du Bois A, Hahmann M, Hasenburg A, Burges A, Loibl S, Gropp M, Huober J, Fink D, Schröder W. Surgery in recurrent ovarian cancer: the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie (AGO) DESKTOP OVAR trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:1702-1710. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Chi DS, McCaughty K, Diaz JP, Huh J, Schwabenbauer S, Hummer AJ, Venkatraman ES, Aghajanian C, Sonoda Y, Abu-Rustum NR. Guidelines and selection criteria for secondary cytoreductive surgery in patients with recurrent, platinum-sensitive epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2006;106:1933-1939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Oksefjell H, Sandstad B, Tropé C. The role of secondary cytoreduction in the management of the first relapse in epithelial ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:286-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Tian WJ, Jiang R, Cheng X, Tang J, Xing Y, Zang RY. Surgery in recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: benefits on Survival for patients with residual disease of 0.1-1 cm after secondary cytoreduction. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:244-250. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Sehouli J, Richter R, Braicu EI, Bühling KJ, Bahra M, Neuhaus P, Lichtenegger W, Fotopoulou C. Role of secondary cytoreductive surgery in ovarian cancer relapse: who will benefit? A systematic analysis of 240 consecutive patients. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:656-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Shih KK, Chi DS, Barakat RR, Leitao MM. Tertiary cytoreduction in patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer: an updated series. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;117:330-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Fotopoulou C, Richter R, Braicu IE, Schmidt SC, Neuhaus P, Lichtenegger W, Sehouli J. Clinical outcome of tertiary surgical cytoreduction in patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:49-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Bristow RE, Puri I, Chi DS. Cytoreductive surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:265-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Munkarah AR, Coleman RL. Critical evaluation of secondary cytoreduction in recurrent ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95:273-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Harter P, Sehouli J, Reuss A, Hasenburg A, Scambia G, Cibula D, Mahner S, Vergote I, Reinthaller A, Burges A. Prospective validation study of a predictive score for operability of recurrent ovarian cancer: the Multicenter Intergroup Study DESKTOP II. A project of the AGO Kommission OVAR, AGO Study Group, NOGGO, AGO-Austria, and MITO. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21:289-295. [PubMed] |

| 50. | Zang RY, Harter P, Chi DS, Sehouli J, Jiang R, Tropé CG, Ayhan A, Cormio G, Xing Y, Wollschlaeger KM. Predictors of survival in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer undergoing secondary cytoreductive surgery based on the pooled analysis of an international collaborative cohort. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:890-896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Tian WJ, Chi DS, Sehouli J, Tropé CG, Jiang R, Ayhan A, Cormio G, Xing Y, Breitbach GP, Braicu EI. A risk model for secondary cytoreductive surgery in recurrent ovarian cancer: an evidence-based proposal for patient selection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:597-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Galaal K, Naik R, Bristow RE, Patel A, Bryant A, Dickinson HO. Cytoreductive surgery plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;CD007822. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Helm CW. Current status and future directions of cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2012;21:645-663. [PubMed] |

| 54. | Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Hanker LC, Loibl S, Burchardi N, Pfisterer J, Meier W, Pujade-Lauraine E, Ray-Coquard I, Sehouli J, Harter P, du Bois A. The impact of second to sixth line therapy on survival of relapsed ovarian cancer after primary taxane/platinum-based therapy. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2605-2612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Ledermann JA, Raja FA. Clinical trials and decision-making strategies for optimal treatment of relapsed ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47 Suppl 3:S104-S115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |