Published online Mar 3, 2023. doi: 10.5317/wjog.v12.i2.11

Peer-review started: June 29, 2022

First decision: August 1, 2022

Revised: September 2, 2022

Accepted: February 17, 2023

Article in press: February 17, 2023

Published online: March 3, 2023

Processing time: 246 Days and 16 Hours

Spilled gallstones from previous cholecystectomy is not an uncommon situation. It may further mimic neoplastic disease and can be misled by fluorine 18 fluorodeoxyglucose position emission tomography with computed tomography ([18F]FDG PET/CT).

A 63 year-old patient was diagnosed with a cancer of the cervix. Pretreatment [18F]FDG PET/CT showed a peritoneal lesion suspicious for metastasis. Surgical exploration and histologic examination revealed the lesion to be a spilled gallstone from a previous cholecystectomy.

[18F]FDG PET/CT carries pitfalls since benign conditions such as intraperitoneal gallstones may be confused as malignant lesions. This case highlights the importance to be aware of the possible implications of dropped gallstones for the future, minimize its occurrence, and make all efforts to properly evaluate cancer staging, particularly for the cervix cancer.

Core Tip: Proper staging with imaging and fluorine 18 fluorodeoxyglucose position emission tomography with computed tomography ([18F]FDG PET/CT) is primordial for the management of cervical cancer. [18F]FDG PET/CT however carries pitfalls since benign conditions may be confused as malignant lesions. Spilled gallstones from previous cholecystectomy may be misdiagnosed as neoplastic disease with [18F]FDG PET/CT.

- Citation: Chan KL, Lord M, McNamara D, Désilets É, Bergeron E. Spilled gallstone mimicking metastasis from cervix cancer on positron emission tomography – computed tomography. World J Obstet Gynecol 2023; 12(2): 11-16

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6220/full/v12/i2/11.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5317/wjog.v12.i2.11

Fluorine 18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) position emission tomography with computed tomography ([18F]FDG PET/CT) is nowadays a ubiquitous tool in the differentiation of benign from malignant tumors, in the staging of cancers, and in the follow-up of patients who have undergone surgery, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy[1,2]. It allows for the detection of metastases or recurrences of cancer which typically exhibit increased glucose metabolism[1]. However, pitfalls may occur with increased FDG uptake in some benign conditions[1,3].

We present a patient who has been diagnosed with a cervical cancer. A [18F]FDG PET/CT for staging showed a suspicious lesion for peritoneal metastasis was discovered. After surgery and pathologic examination, the lesion was diagnosed as a dropped gallstone from a previous cholecystectomy.

The patient suffered from a post-menopausal bleeding.

A 63-year-old caucasian female was referred with a history of post-menopausal bleeding. Vaginal bleeding was irregular with small quantity but increased with physical activities. She was not sexually active at the time. She had no fatigue or loss of weight. She did not report any abdominal or pelvic pain.

She had a laparoscopic cholecystectomy without known complications three years before. The gallbladder was fibrotic and sheared during dissection. There was no awareness of gallstones left unretrieved. She has no medical problem.

The patient looked in good shape. There was no abdominal pain. No abdominal mass was palpated. On gynecological examination, the exocervix appeared normal but necrotic tissue could be seen at the endocervix.

Hemoglobin level was normal. There was no increase of tumor markers. Endocervical curettage and endometrial biopsy were performed. The biopsy revealed clear cell carcinoma.

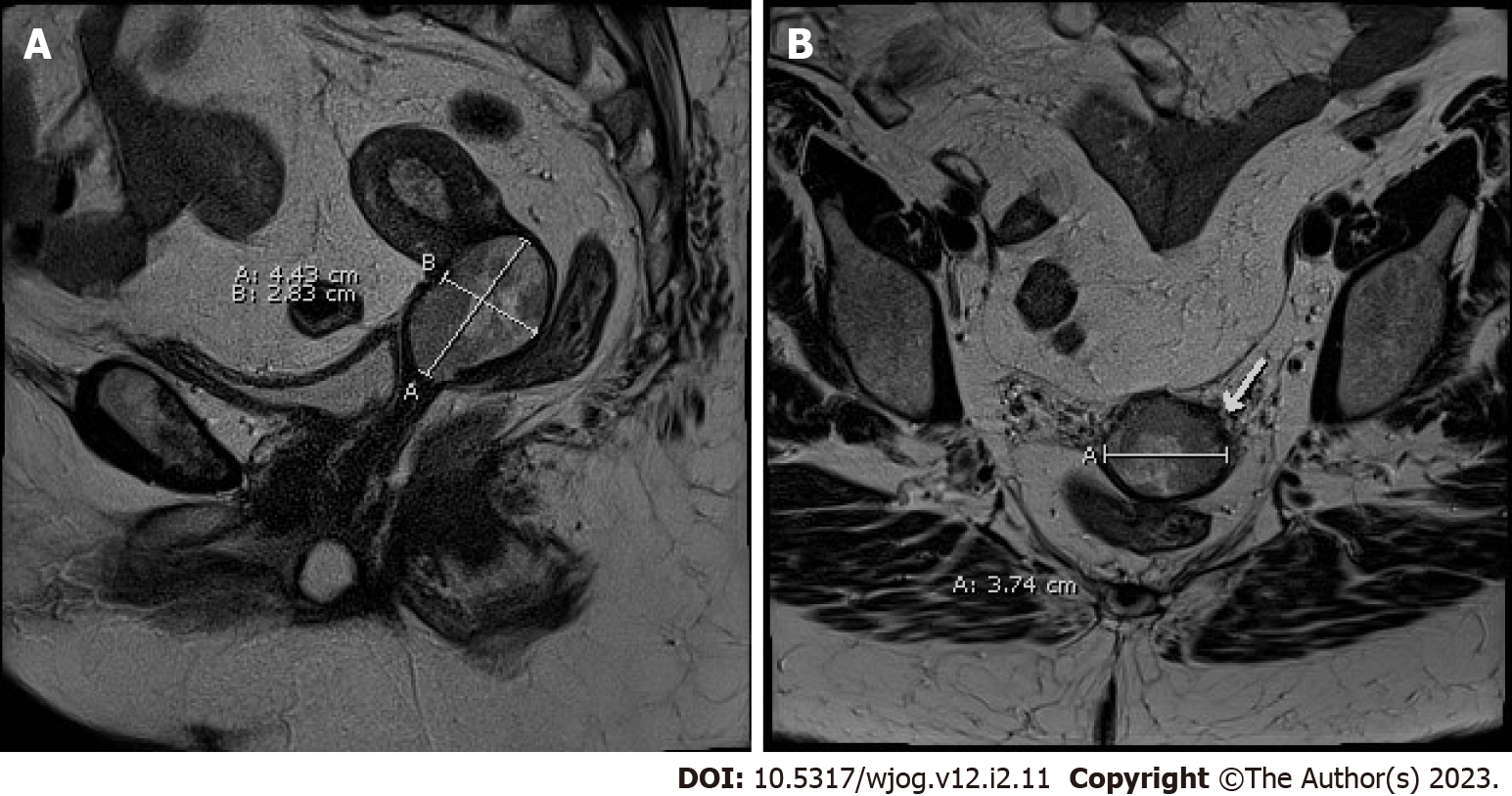

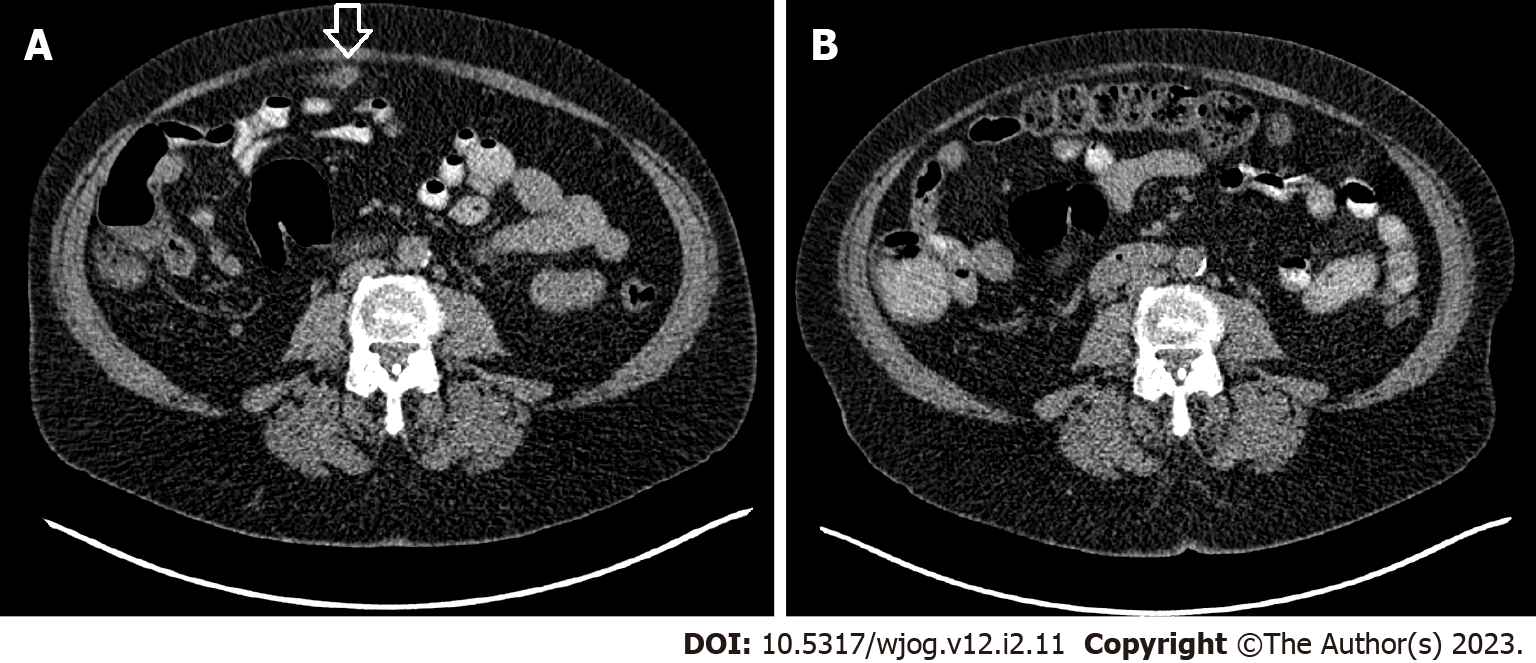

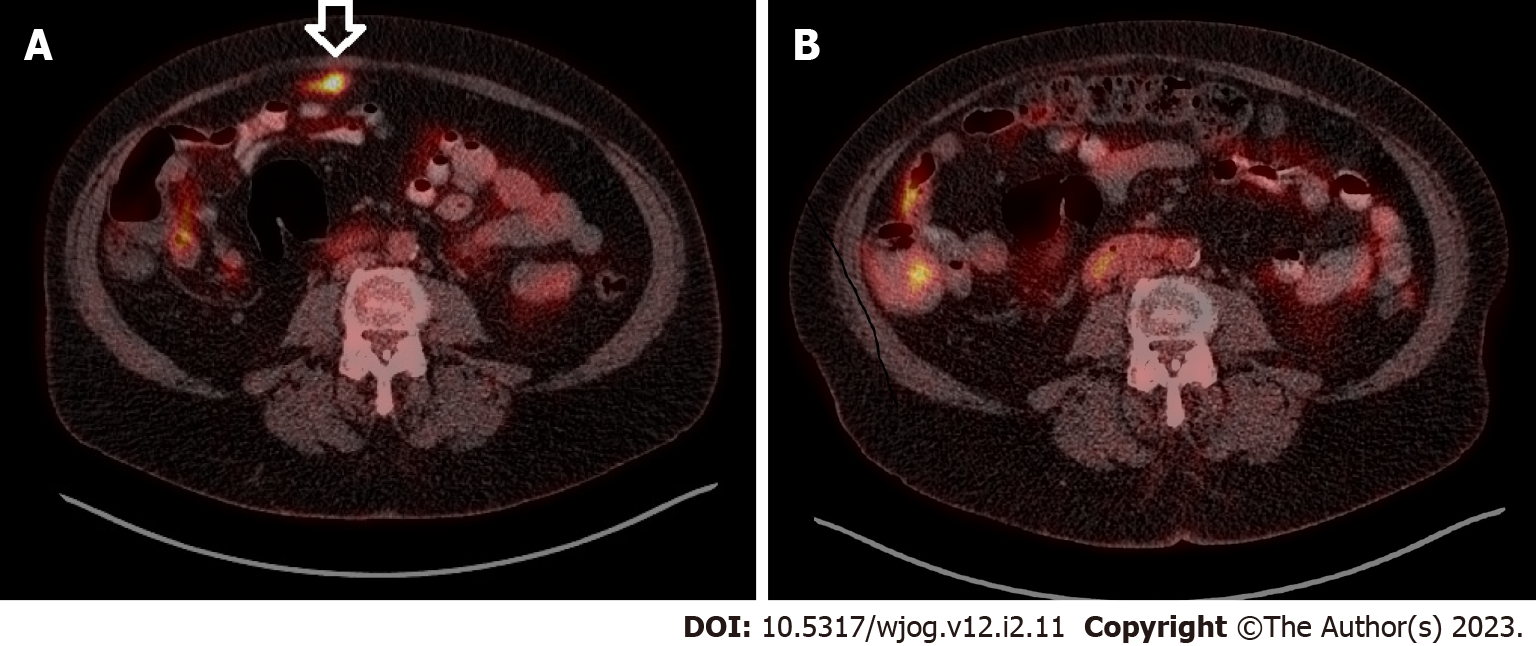

A magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis was performed which showed a 4.4 cm × 3.7 cm × 2.8 cm lesion in the cervix with extension to the lower third of the endometrium (Figure 1). The parametrium, vagina and adnexa were negative for cancer but a 9 mm lymph node was seen in the right iliac region. A CT scan of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis showed a suspicious intraperitoneal lesion besides and in front of the transverse colon (Figure 2A). No suspicious adenopathy was identified. [18F]FDG PET/CT revealed a hypermetabolic (SUV = 6) area 1 cm × 4 cm in size embedded in the peri-colic fat of the transverse colon in addition to a hypermetabolic cervical lesion (Figure 3A).

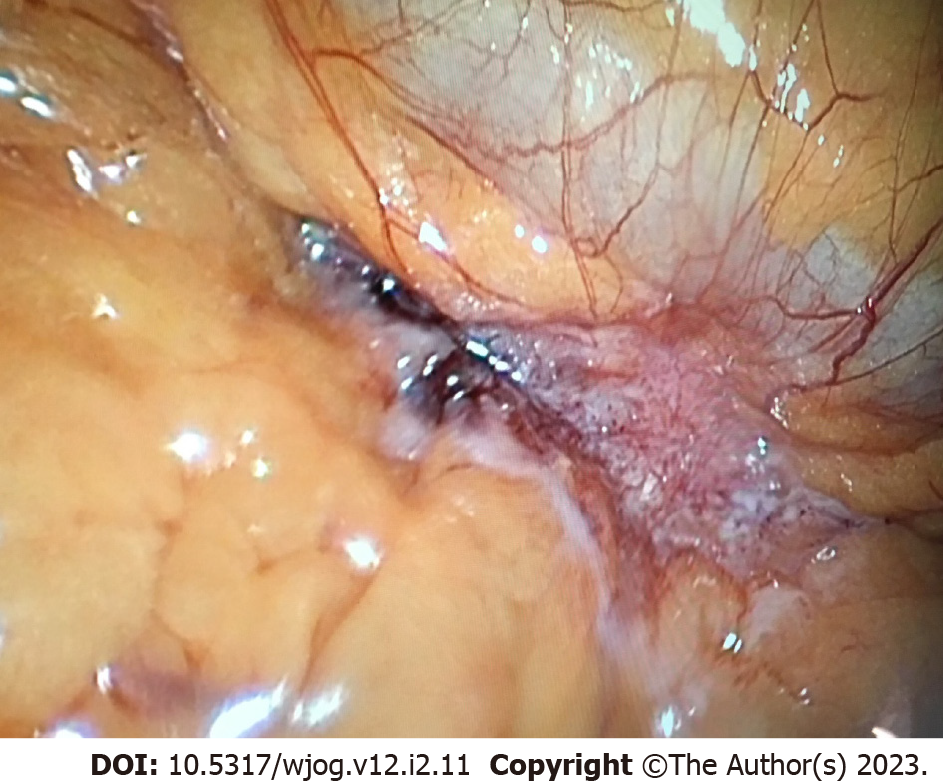

The patient underwent a diagnostic laparoscopy to investigate this unusual site of possible metastasis. At the same time, sentinel node biopsy was carried out. At surgery, a dark colored nodule was found close to but not adherent to the mid transverse colon (Figure 4). It was dissected completely without any bleeding and the surgery was completed with bilateral sentinel lymph node biopsy. A frozen section analysis was done which showed a hard calculus without signs of malignancy. The final pathology showed an 8 mm diameter calculus surrounded by acute and chronic inflammation with abscess formation and granuloma as well as negative sentinel nodes.

Clear cell carcinoma of the cervix, stage IB3. Dropped intraperitoneal gallstone with surrounding inflammation. Absence of peritoneal metastases.

Combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy were prescribed.

CT scan and [18F]FDG PET/CT were performed 4 mo post treatment and showed no residual activity in the previous hypermetabolic site (Figures 2B and 3B). There was discrete activity in the uterus which was confirmed to be benign by magnetic resonance imaging. The patient currently has no evidence of disease at 20 mo after treatment. The case is summarized in Table 1.

| History | History of post-menopausal bleeding, past laparoscopic cholecystectomy in a 63-year-old female |

| Examination | Exocervix normal; Endocervix showing necrotic tissue |

| Endometrial biopsy | Clear cell carcinoma |

| Magnetic resonance imaging | 4.4 cm × 3.7 cm × 2.8 cm lesion in the cervix with extension to the lower third of the endometrium 9 mm right iliac node |

| Computed tomography | Suspicious intraperitoneal lesion in front the transverse colon |

| [18F]FDG PET/CT | 1 cm × 4 cm hypermetabolic area in the peri-colic fat of the transverse colon; Hypermetabolic cervical lesion |

| Diagnostic laparoscopy and excisional biopsy | 8-mm diameter calculus surrounded by acute and chronic inflammation with abscess formation and granuloma |

| Sentinel node biopsy | Negative |

| Treatment | Combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy |

| [18F]FDG PET/CT (after 4 mo) | No residual activity in the previous hypermetabolic site; Normal uterine activity |

| Follow-up | No recurrence after 20 mo |

Cervical cancer accounts for 1.3% of all new female cancers and 1.1% of all female cancer deaths in Canada[4]. Cervical cancer staging is based on tumor size, vaginal or parametrial involvement, bladder/rectum extension, and distant metastases[2]. [18F]FDG PET/CT is used for the evaluation of patients with cervical cancer[2,3]. Proper staging is mandatory in the planning of treatment of cancer of the cervix[2] and [18F]FDG PET/CT is nowadays used routinely in developed countries[2,5]. Sensitivity and specificity are respectively 53%-73% and 90%-97% for the detection of lymph node in cervical cancer[5].

Accidental gallstone spillage is often encountered during laparoscopic cholecystectomy[6]. Incidence of gallbladder perforation is 18.3%, gallstone spillage 7.3%, and unretrieved peritoneal gallstones 2.4%[7]. There is however no recent evaluation of the incidence of gallbladder perforation and spilled gallstones[8]. Despites better awareness of possible problems with dropped gallstones, incidence has probably not changed.

More than 90% of lost gallstones remain asymptomatic[9] with an estimate of 8.5% leading to a complication[10]. Such complications may occur such as localized infection or abscess, which are the most frequent[9-12], as well as inflammation, fibrosis, erosion or fistulization[6,9]. The occurrence of complication has been reported up to fifteen[9,13] and even twenty years[14] after cholecystectomy.

Dropped gallstones can even mimic malignancies, lymph nodes, metastatic implants or carcinomatosis[1,6,9,12,15], so diagnosis is particularly challenging in the absence of histological confirmation[11]. False positive [18F]FDG PET/CT occurs in many conditions as a result of granulomatous disease or inflammation, foreign body reaction, and surgical changes[3]. In the present case, the lesion captured FDG, because of the inflammation surrounding the stone, not the stone itself[16,17]. CT scan also demonstrated a suspicious mass. In the presence of a cervical cancer, even without regional nodes, the occurrence of such a mass in the peritoneal cavity is, until proven otherwise, a metastatic lesion. Only removal and analysis of the mass could solve the diagnostic challenge and eliminate a peritoneal implant. Even at surgical exploration, the lesion appeared suspicious of neoplastic disease (Figure 4).

Some images of this case have been reported[18]. However, unlike what was showed, this report demonstrates the disappearance of the lesion on subsequent imaging studies (Figures 2 and 3) further proving that it has been removed. Moreover, the negative yet essential pathologic analysis definitively ascertains its benign nature. Consequently, the cancer was finally downstaged from stage IV to Stage IB3. In this patient with cervical cancer, optimal staging was mandatory as it drastically modified potential prognosis and management.

This case demonstrates that [18F]FDG PET/CT carries potential pitfalls since benign conditions may be confused as malignant lesions[1,3], as for intraperitoneal dropped gallstones from a previous cholecystectomy[1,6,15] which is not a so rare situation[7]. Even in case of known and documented dropped gallstones, diagnosis remains markedly challenging, and biopsy or even surgical exploration may become necessary for proper staging and management.

Staging is essential in order to properly manage cervical cancers and adequately evaluate prognosis. [18F]FDG PET/CT is the mainstay in the evaluation of patients with cervical cancer. However, it carries some pitfalls as in cases of previous dropped gallstones which could mimic neoplastic or metastatic disease.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: Canada

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Fu DL, China; Gamarra LF, Brazil S-Editor: Liu XF L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu XF

| 1. | Tan GJ, Berlangieri SU, Lee ST, Scott AM. FDG PET/CT in the liver: lesions mimicking malignancies. Abdom Imaging. 2014;39:187-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Marth C, Landoni F, Mahner S, McCormack M, Gonzalez-Martin A, Colombo N; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Cervical cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:iv72-iv83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 503] [Cited by in RCA: 504] [Article Influence: 63.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Blake MA, Singh A, Setty BN, Slattery J, Kalra M, Maher MM, Sahani DV, Fischman AJ, Mueller PR. Pearls and pitfalls in interpretation of abdominal and pelvic PET-CT. Radiographics. 2006;26:1335-1353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Government of Canada, Public Health Agency. Report on Cervical cancer, 2017. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/chronic-diseases/cancer/cervical-cancer.html. |

| 5. | Patel CN, Nazir SA, Khan Z, Gleeson FV, Bradley KM. 18F-FDG PET/CT of cervical carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:1225-1233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kayashima H, Ikegami T, Ueo H, Tsubokawa N, Matsuura H, Okamoto D, Nakashima A, Okadome K. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver in association with spilled gallstones 3 years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: report of a case. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2011;4:181-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Woodfield JC, Rodgers M, Windsor JA. Peritoneal gallstones following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: incidence, complications, and management. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:1200-1207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Demirbas BT, Gulluoglu BM, Aktan AO. Retained abdominal gallstones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a systematic review. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2015;25:97-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Capolupo GT, Mascianà G, Carannante F, Caricato M. Spilled gallstones simulating peritoneal carcinomatosis: A case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;48:113-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zehetner J, Shamiyeh A, Wayand W. Lost gallstones in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: all possible complications. Am J Surg. 2007;193:73-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Akhtar A, Bukhari MM, Tariq U, Sheikh AB, Siddiqui FS, Sohail MS, Khan A. Spilled Gallstones Silent for a Decade: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Cureus. 2018;10:e2921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nayak L, Menias CO, Gayer G. Dropped gallstones: spectrum of imaging findings, complications and diagnostic pitfalls. Br J Radiol. 2013;86:20120588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Arishi AR, Rabie ME, Khan MS, Sumaili H, Shaabi H, Michael NT, Shekhawat BS. Spilled gallstones: the source of an enigma. JSLS. 2008;12:321-325. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Nugent L, Chandran P. Need brooks no delay. Peritoneo-cutaneous fistula formation secondary to gallstone dropped at laparoscopic cholecystectomy 20 years previously: a case report. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018:rjy013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kim J, Siegel A, Yen SP, Seltzer M. Subdiaphragmatic gallstone mimicking hepatic malignancy on FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2015;40:347-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Aras M, Inanir S, Tuney D. Bouveret's syndrome on FDG PET/CT: a rare life-threatening complication of gallstone disease. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol. 2014;33:125-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ardekani AE, Amini H, Paymani Z, Fard-Esfahani A. False-positive elevated CEA during colon cancer surveillance: a cholecystitis case report diagnosed by PET-CT scan. J Surg Case Rep. 2019;2019:rjz138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pouyez C, Dami M. Gallstone mimicking metastatic cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2021;31:1496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |