Published online May 27, 2014. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v6.i5.358

Revised: January 9, 2014

Accepted: March 17, 2014

Published online: May 27, 2014

An eleven-year-old clinically dysmorphic and developmentally retarded male child presenting with complaints of 5 episodes of recurrent cholestatic jaundice since 3 years of age was evaluated. Imaging revealed features consistent with congenital extrahepatic portocaval shunt (Abernethy type 1b), multiple regenerative liver nodules and intrahepatic biliary radical dilatation. The presence of ductal paucity and trisomy 8 were confirmed on liver biopsy and karyotyping. The explanation for unusual and previously unreported features in the present case has been proposed.

Core tip: This study highlights the association between the congenital extrahepatic portocaval shunt with hepatic ductal paucity and trisomy 8 for the first time in the world literature. Although the exact pathophysiology remains uncertain, plausible explanations are proposed.

- Citation: Sood V, Khanna R, Alam S, Rawat D, Bhatnagar S, Rastogi A. Ductal paucity and Warkany syndrome in a patient with congenital extrahepatic portocaval shunt. World J Hepatol 2014; 6(5): 358-362

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v6/i5/358.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v6.i5.358

An eleven-year-old male child was admitted with recurrent episodes of cholestatic jaundice since age three. Each episode was associated with fever, pruritus and clay colored stool, lasting for 10-15 d. There was no history of variceal bleeding, respiratory difficulty, altered sensorium, abdominal distension, oliguria, loose stool, blood in stool, rash, joint pains or any other autoimmune phenomena.

The patient was born preterm at 8.5 mo gestation and had indirect hyperbilirubinemia without kernicterus, and was managed with phototherapy. The antenatal period was uneventful. Developmentally, his motor development coincided with his chronological age, but mental age lagged by 5 years.

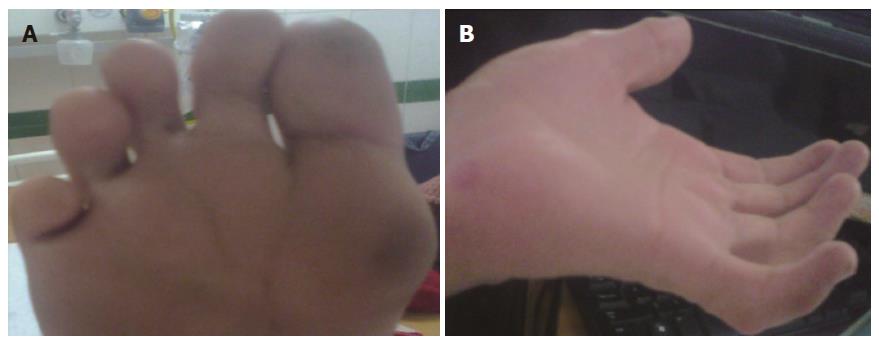

On examination, his vital parameters were stable. Anthropometry revealed severe malnutrition. There was no pallor, icterus, clubbing, cyanosis, edema, or any peripheral symptoms of chronic liver disease. Dysmorphic features were present and included triangular facies, deep set eyes, antimongoloid slant, bulbous upturned nose tip, mal-aligned upper teeth, retrognathia, camptodactyly, single crease on little finger, multiple finger webs and deep plantar furrows (Figure 1). Ophthalmological examination revealed clear lens with normal cornea, iris and fundus. Orthopedic assessment revealed pectus carinatum and elbow contractures with restriction of extension movements. The spine was normal. Abdominal examination revealed no organomegaly or free fluid. Neurological examination was normal with preservation of higher mental, motor and sensory functions. Cardiovascular and respiratory systems were normal.

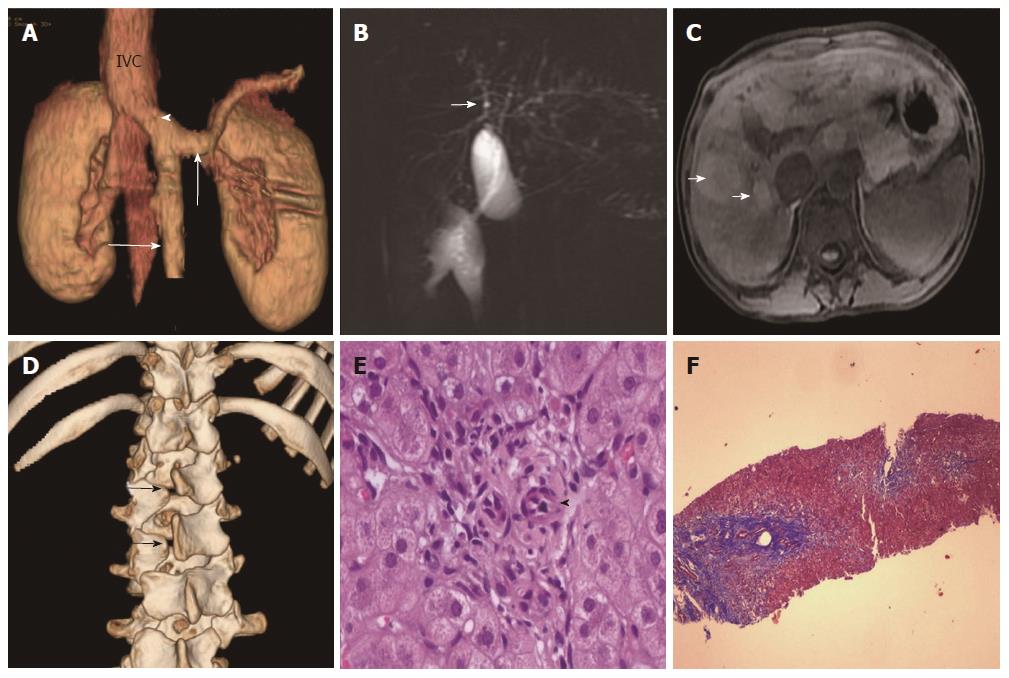

Laboratory parameters revealed conjugated hyperbilirubinemia with elevated liver enzymes. Synthetic function markers (albumin and prothrombin time) and lipid profile were normal. Serology for hepatitis A, B and C viral infection was negative (Table 1). Doppler ultrasonography (USG) of the abdomen revealed coarse liver with anomalous drainage of the extra-hepatic portal vein (PV) into the inferior vena cava (IVC) with non-visualization of intra-hepatic PV radicles. These findings were confirmed on contrast-enhanced computerized tomography (CT) (Figure 2A), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and cholangiopancreaticography (MRCP). Imaging also revealed bilateral nephromegaly and dilatation of intrahepatic biliary radicles (IHBRD, left > right), without evidence of stricture, beading, mass or calculi in the biliary tree (Figure 2B). On MRI, numerous nodules were seen in both liver lobes which were hyper-intense on T1 and showed variable signal on T2 (Figure 2C). These imaging features were consistent with congenital extrahepatic portocaval shunt (CEPS or Abernethy type 1b), multiple regenerative liver nodules and IHBRD.

| Parameter | Age | |||

| 6 yr | 10 yr | 11 yrFirst contact | 11.25 yrFollow-up (episode of cholangitis) | |

| Hb (g/dL) | - | 10.7 | 11 | 13.6 |

| TLC (cells/mm3) | - | 11300 | 11600 | 22200 |

| Platelets (cells 1000/mm3) | - | 329 | 253 | 213 |

| Bilirubin (T/D) (mg/dL) | 0.8/0.5 | 1.1/0.5 | 1.5/0.6 | 3.18/1.92 |

| AST (IU/L) | 100 | 71 | 60 | 242 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 104 | 43 | 71 | 148 |

| SAP (IU/L) | 410 | 513 | 550 | 604 |

| GGT (IU/L) | - | - | 165 | 224 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.7 | 3.5 | 3.7 | 3.3 |

| INR | - | - | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| Ammonia (μg/dL) | - | - | 155 | 229 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | - | 6.5 | - | 1.81 |

| Fasting blood sugar (mg/dL) | - | - | 42 | 72 |

| pO2 (mmHg) on room air | - | - | 79.3 | 80 |

| A-aO2 gradient (mmHg) | - | - | 26.4 | 21 |

| BMI Z-score | - | - | -3.5 | -3.07 |

| Height Z-score | - | - | -1.7 | -1.9 |

Subsequent evaluation revealed fasting hypoglycemia and hyperammonemia. Arterial blood gas analysis showed high alveolar-arterial gradient with hypoxemia on room air. Echocardiography showed structurally normal heart with severe shunting on injection of saline contrast, thus suggesting moderate hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS). Alpha-fetoprotein concentration was normal. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed no varices. A skeletal survey revealed spina bifida (Figure 2D). Brain imaging was normal. Karyotyping showed mosaic trisomy of chromosome 8. Liver biopsy revealed maintained acinar architecture with mild cholestasis; portal tracts showed total absence of PV profiles, ductal paucity (bile duct: portal tract ratio of 0.3), conspicuous hepatic arteries and periportal fibrosis (Figure 2E and F).

The child was started on sodium benzoate, uncooked cornstarch diet and pentoxiphylline. His fasting hypoglycemia, hyperammonemia and hypoglycemia got corrected after one month of follow-up. He had another episode of jaundice with fever four months later which was managed conservatively. The patient’s family was counselled regarding the prognosis including the possible need for liver transplantation (LTx).

Congenital extrahepatic portosystemic shunts (CEPS), or Abernethy malformation, is a rare congenital anomaly characterized by shunting of portal venous blood to the systemic circulation. On the basis of the presence of the PV and its intrahepatic radicles and the type of shunt, these malformations were classified by Morgan and Superina as (1) Type 1 (85%), with complete diversion of portal venous blood into the systemic circulation and total absence of intrahepatic PV branches; this was further subclassified as Type 1a, where splenic (SV) and superior mesenteric veins drain separately into the IVC, and Type 1b, when these veins drain after the formation of a short PV trunk, which drains into the IVC in an end-to-side fashion; and (2) Type 2, with intact PV and the presence of a side-to-side portocaval shunt[1]. A recent review suggested a classification based on anatomical site of origin and termination, type of communication with the systemic vein and number of communications[2]. CEPS are known to be associated with various congenital anomalies, particularly cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, skeletal and neurological, and genetic syndromes (Turner’s and Goldenhar’s)[3]. Our case was Type 1b CEPS without any other major structural malformations, except dysmorphism and spina bifida. He also had nephromegaly with structurally normal kidneys on imaging.

Clinical manifestations in CEPS occur either due to direct entry of intestinal blood and toxins into the systemic circulation or due to long-standing deprivation of PV blood supply with subsequent effects on liver regeneration and metabolism; some features are secondary to associated congenital abnormalities. As per recent reviews, the median age at presentation is 3.7 years with common modes being hypoxemia secondary to HPS or portopulmonary hypertension (26%-34%), galactosemia (raised blood and urinary concentrations of galactose without enzyme deficiency) (26%), hepatic encephalopathy (HE) or hyperammonemia (9%-34%), neonatal cholestasis (13%) and incidental detection on imaging (9%-21%). Less common presentations are liver dysfunction, hypoglycemia, hepatocellular carcinoma and gastrointestinal bleeding[2,4]. Our patient developed growth failure, hyperammonemia, hypoglycemia, HPS (low partial pressure of oxygen and high alveolar to arterial oxygen gradient on room air) as well as recurrent jaundice (Table 1).

Focal hepatic lesions are common (35%-50%) in CEPS. As the liver is deprived of hepatotrophic factors such as insulin and glucagon, it undergoes atrophy with concomitant regeneration. Regenerative changes manifest as focal nodular hyperplasia, nodular regenerative hyperplasia, hepatocellular adenoma, and rarely cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatoblastoma[2-4]. Our case had multiple regenerative nodules on imaging with normal AFP.

The diagnosis is established with USG Doppler and CT/MR angiography. Liver biopsy is needed for classification and subsequent management, as well as to establish the nature of the focal lesions. Liver histology in CEPS usually show absence or hypoplastic PVs, thickened hepatic arteries, minimal or moderate portal fibrosis, proliferation of thin vascular, capillary, or lymphatic structures in portal and periportal regions, and occasionally focal ductular proliferation[2]. Our case showed the absence of PV with prominent hepatic arteries and F2 fibrosis on Metavir staging. In addition, our case had ductal paucity, a finding which has not been previously described in CEPS.

Trisomy 8 or Warkany syndrome is a rare disorder. The majority of cases are mosaic as complete trisomy is usually lethal in fetal life. Deep plantar furrow is pathognomonic. Patients also have corneal clouding, strabismus, low set or abnormally shaped ears, bulbous nose tip, cleft palate, camptodactyly, clinodactyly, deep palmar furrow, anomalies related to the skeletal, cardiovascular and urogenital system, and mild to moderate mental retardation[5,6]. Most of these findings were present in our case, and to the best of our knowledge this is the first report of an association between CEPS and trisomy 8.

The presence of recurrent jaundice with bile ductal paucity and IHBRD were unusual features in our case. Recurrent jaundice in CEPS has been described in the literature, but no explanation has been provided[7]. During embryogenesis, PV plays a crucial role in the formation and remodeling of the ductal plate. Conversely, lack of remodeling is frequently associated with abnormalities in the ramification pattern of PV. Thus, both ductal plate malformation (DPM) and PV abnormalities may be inter-related. DPM is also associated with Caroli’s syndrome and thus may also explain IHBRD seen in our case[8]. Another possible explanation is a pressure effect on the biliary system by the prominent dilated hepatic artery leading to recurrent cholangitis and ductal paucity secondary to chronic biliary obstruction. Another genetic defect, Alagille’s syndrome, associated with mutations in Jagged1 or NOTCH2 genes, is also associated with ductal paucity and dysmorphic features, but our child didn’t have other phenotypic features to suggest the disorder[9].

An algorithm for the management of CEPS has been suggested depending on the type of abnormality, symptoms and the presence of liver tumor[2]. Acceptable therapeutic options include LTx in type 1 and shunt occlusion (radiological or interventional) in type 2 cases. Common indications for LTx include HE or hyperammonemia (38%), pulmonary complications (32%) and tumor (15%)[4]. Authors have also proposed shunt occlusion for type 1 cases, presuming that the miniature hepatopetal vessels may enlarge after the procedure[2]. Our patient had moderate subclinical HPS, hyperammonemia and hypoglycemia along with total absence of PV radicles on liver histology, thus mandating LTx.

We describe a case of CEPS type 1b with trisomy 8 with an unusual presentation manifesting as recurrent jaundice, cholangitis and ductal paucity. We discuss the possible cause of recurrent jaundice and ductal paucity in CEPS.

Recurrent episodes of cholestatic jaundice, dysmorphism, developmental delay.

Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia with elevated liver enzymes, hypoglycemia, hyperammonemia, and hypoxemia with high alveolar-arterial gradient.

Congenital extrahepatic portocaval shunt (Abernethy Type 1b), multiple regenerative liver nodules and dilatation of intrahepatic biliary radicles.

Ductal paucity, conspicuous hepatic arteries and periportal fibrosis.

Anti-hyperammonemia measures, uncooked cornstarch diet and pentoxiphylline.

This is the first report highlighting the association between congenital malformation of portocaval shunt and trisomy 8. The cause of the unusual and previously unreported features in our case such as recurrent jaundice with bile ductal paucity and IHBRD remains unknown.

Congenital extrahepatic portosystemic shunts (CEPS), or Abernethy malformation is a congenital anomaly characterized by shunting of the portal venous blood to the systemic circulation.

CEPS should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a child presenting with developmental delay and liver dysfunction. A simple bedside Doppler ultrasound by an experienced radiologist can help in the identification of this rare anomaly.

Article reports the association between a very rare but known congenital malformation of portocaval shunt with not yet reported hepatic ductal paucity and trisomy 8 and also highlights vascular anomalies as one of the causes of recurrent cholestatic jaundice.

P- Reviewers: Assimakopoulos SF, La Mura V, Makishima M, Vivarelli M S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: Webster JR E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Morgan G, Superina R. Congenital absence of the portal vein: two cases and a proposed classification system for portasystemic vascular anomalies. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:1239-1241. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 308] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bernard O, Franchi-Abella S, Branchereau S, Pariente D, Gauthier F, Jacquemin E. Congenital portosystemic shunts in children: recognition, evaluation, and management. Semin Liver Dis. 2012;32:273-287. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Alonso-Gamarra E, Parrón M, Pérez A, Prieto C, Hierro L, López-Santamaría M. Clinical and radiologic manifestations of congenital extrahepatic portosystemic shunts: a comprehensive review. Radiographics. 2011;31:707-722. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 108] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sakamoto S, Shigeta T, Fukuda A, Tanaka H, Nakazawa A, Nosaka S, Uemoto S, Kasahara M. The role of liver transplantation for congenital extrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Transplantation. 2012;93:1282-1287. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hale NE, Keane JF. Piecing together a picture of trisomy 8 mosaicism syndrome. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2010;110:21-23. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Karadima G, Bugge M, Nicolaidis P, Vassilopoulos D, Avramopoulos D, Grigoriadou M, Albrecht B, Passarge E, Annerén G, Blennow E. Origin of nondisjunction in trisomy 8 and trisomy 8 mosaicism. Eur J Hum Genet. 1998;6:432-438. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 49] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Witters P, Maleux G, George C, Delcroix M, Hoffman I, Gewillig M, Verslype C, Monbaliu D, Aerts R, Pirenne J. Congenital veno-venous malformations of the liver: widely variable clinical presentations. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:e390-e394. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 67] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Desmet VJ. Congenital diseases of intrahepatic bile ducts: variations on the theme “ductal plate malformation”. Hepatology. 1992;16:1069-1083. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 425] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 429] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Subramaniam P, Knisely A, Portmann B, Qureshi SA, Aclimandos WA, Karani JB, Baker AJ. Diagnosis of Alagille syndrome-25 years of experience at King’s College Hospital. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:84-89. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |