修回日期: 2016-05-10

接受日期: 2016-05-16

在线出版日期: 2016-06-18

Edmonton方案的提出推动了胰岛移植的加速发展. 雷帕霉素作为Edmonton方案中推荐的免疫抑制药物得到了人们更多的关注. 雷帕霉素的衍生物(依维莫司、地磷莫司、佐他莫司、替西罗莫司)也引起了人们的兴趣. 人们在探讨他们的免疫抑制作用和抗肿瘤作用的同时, 发现他们可引起血糖升高等胰岛毒性症状. 他们能否成为合适的胰岛移植抗排斥药物还有待进一步研究. 本文就雷帕霉素及其衍生物的作用、应用进展和他们对胰岛的毒性作用作一综述.

核心提示: 雷帕霉素是Edmonton方案中推荐的抗排斥药物. 然而却在基础研究和临床应用中发现他和他的衍生物对胰岛具有毒性, 可引起高血糖的发生. 那么雷帕霉素及其衍生物对胰岛究竟有着怎样的作用, 本文将作一详细阐述.

引文著录: 张娟, 付嘉钊, 洪诗福, 江红, 齐忠权, 黄昭穗, 夏俊杰. 雷帕霉素及其衍生物对胰岛的毒性作用. 世界华人消化杂志 2016; 24(17): 2667-2675

Revised: May 10, 2016

Accepted: May 16, 2016

Published online: June 18, 2016

The development of islet transplantation has been promoted by the proposal of the Edmonton protocol. Rapamycin, as a recommended immunosuppressive medicine of the Edmonton protocol, has been getting extraordinarily popular. At the same time, derivatives of rapamycin (everolimus, deforolimus, zotarolimus and temsirolimus) have also garnered great interest. While the immunosuppressive and anti-cancer effects of rapalogs were being discussed actively, researchers discovered their cytotoxic effect on pancreatic islets. Whether they could be ideal drugs for anti-rejection after islet transplantation needs further study. This review aims to elucidate the function and application of rapalogs as well as their toxicity to pancreatic islets.

- Citation: Zhang J, Fu JZ, Hong SF, Jiang H, Qi ZQ, Huang ZS, Xia JJ. Toxicity of rapamycin and its derivatives to pancreatic islets. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2016; 24(17): 2667-2675

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v24/i17/2667.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v24.i17.2667

胰岛移植被认为是治疗Ⅰ型糖尿病的最佳手段. Edmonton方案的提出也使胰岛移植进入到了一个新的快速发展的阶段. 然而研究表明, 免疫抑制剂在抑制受体对胰岛移植物排斥的同时, 他们本身也对胰岛有一定的毒性作用. 在应用雷帕霉素(Rapamycin, Rapa)作为抗免疫排斥药和抗肿瘤药物的临床实践中发现, 接受Rapa的治疗的部分患者会出现高血糖现象. Rapa的衍生物依维莫司(Everolimus, Eve)在使用过程中也出现了类似的现象. 那么Rapa对胰岛的毒性作用到底怎样, Eve以及其他RAPA的衍生物对胰岛毒性如何, 至今鲜有详细阐述. 本文就Rapa及其衍生物的免疫抑制作用和对胰岛的毒性作用进行综述.

胰岛移植, 是将自体或异体胰腺组织中的胰岛分离提纯后植入患者体内的技术, 目前已经开始应用于临床治疗中. 胰岛移植与胰腺移植相比具有移植物内容单纯, 免疫源性低, 来源广泛, 手术方式简单, 术后并发症少等诸多优点[1-5]. 这些优点使得胰岛移植更有潜力成为治疗Ⅰ型糖尿病的有效方法. 胰岛移植的概念很早就被提出[6]. 20世纪早期, 英国外科医生英国Charles就已经试图通过移植胰腺组织的方法应用到临床. 1990年在匹兹堡大学成功进行了第一例胰岛移植实验[7].

尽管胰岛移植在短短时间内取得了飞跃的进步, 但是胰岛移植取得的效果并不理想. 直到2000年, James改进了胰岛的提取方法, 采用不含糖皮质激素的新型免疫抑制方案. 这种方案使得同种异体胰岛移植成功率大为提高, 被称为Edmonton方案. 该方案的提出, 促使胰岛移植取得质的飞跃与进步[1].

2004年Edmonton小组开展了一项包括65例患者的临床研究, 在随访中发现胰岛移植后患者的β细胞功能随着时间呈进行性丧失; 随访结果显示在胰岛移植5年后, 尽管有80%的患者的胰岛仍存在部分功能, 但是只有10%的患者完全脱离胰岛素[8]. 同样, 在2006年进行了一项包括36例患者的国际多中心实验对Edmonton方案进行验证. 移植1年后随访结果显示只有16例患者完全脱离胰岛素, 10例患者的移植物有部分存在功能, 而其余10例患者移植物的胰岛功能则完全丧失, 移植3年后随访只有1例患者完全脱离胰岛素[2]. 随后, 有研究者提出他克莫司(Tacrolimus, Tac, FK506)和Rapa可能会抑制β细胞的再生, 对胰岛有毒性作用, 长期使用还有肾毒性等不良反应.

改进胰岛移植胰岛分离方法、寻找新的胰岛移植供体来源以及免疫抑制剂的开发, 是胰岛移植的研究方向. 其中由于免疫抑制剂的选择直接影响到移植物生存期, 目前是人们最关心的研究热点.

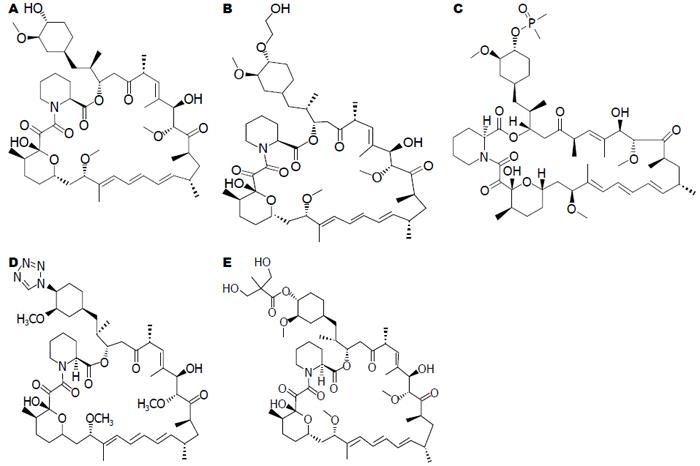

Rapa是1975年在太平洋Easler岛土壤样品中发现的一种亲脂性大环内酯抗生素, 是一种用于器官移植的免疫抑制剂. 他能降低器官移植患者中恶性肿瘤的发生率, 因此应用于器官移植中比FK506更具优势[9-14]. Rapa为哺乳动物靶蛋白(mammalian target of rapamycin, mTOR)抑制剂, 其衍生物也均为mTOR抑制剂. 我国福建微生物研究所曾对51种Rapa的衍生物进行筛选, 其中22个衍生物的免疫抑制活性与Rapa相当. 目前常见的Rapa衍生物主要有: Eve、地磷莫司(Deforolimus, Ridaforolimus, Def)、佐他莫司(Zotarolimus, Zot)、替西罗莫司(Temsirolimus, Tem, CCI-779). 如图1所示为Rapa及其衍生物的化学结构式.

mTOR是Rapa及其衍生物抑制免疫排斥机制中的重要作用靶点, 他是一种分子量为289 kDa非典型丝氨酸/苏氨酸蛋白激酶, 属于进化上十分保守的蛋白激酶. 他是磷脂酰肌醇激酶相关激酶(PIKK)蛋白质家族成员. 他在新陈代谢、细胞生长、增殖中发挥着中心的作用[15-17]. mTOR主要调控有丝分裂原、生长因子以及可用的能量和养分, 他的生物学作用是发挥对下游效应物的磷酸化.

mTOR发挥其活性主要有两种不同复合物形式, 即mTORC1(哺乳动物Rapa靶蛋白复合体1)和mTORC2[18], 相比mTORC1, mTORC2的功能很少被研究. mTORC1, 由mTOR、mLST8、PRAS40、DEPTOR以及RAPTOR组成. mTORC2, 由RICTOR、mLST8、SIN1以及Protor1和2组成[19]. mTOR主要是通过这两种不同的复合物在整条信号通路的下游来发出信号. 目前认为mTOR的上游信号通路主要有两条, 一条是PI3K/Akt/mTOR通路, 该通路与细胞增殖及肿瘤血管形成密切相关; 另一条则是LKB1/AMPK/mTOR信号通路. 而mTOR的下游信号分子主要为P70S6K(P70核糖体S6激酶)和4E-BP1(真核生物转录起始因子结合蛋白), 通过二者增加蛋白质翻译及合成. 有研究[17]显示mTORC1信号通路在调节β细胞大小和功能方面扮演着重要的角色. 当Rapa完全抑制mTORC1时, mTORC2才会受到一点点影响[20].

除此之外, mTOR对免疫细胞也具有不同作用. 如对CD4+ T细胞、记忆性CD8+ T 细胞、抗原提呈细胞及B细胞的分化有促进作用. 而mTOR抑制剂Rapa可阻断树突状细胞对T细胞免疫应答的刺激作用[21,22].

Rapa又名西罗莫司(Sirolimus), 是从吸水性链霉菌(Streptomyces hygroslopicus)发酵液中提取出来的一种大环内酯类抗真菌抗生素[23], 自从1989年发现他强大的免疫抑制作用后, Rapa就被广泛应用于临床及科学研究. 1999年美国惠氏制药成功研制出可通过口服用药的Rapa. 1999-09, Rapa被美国美国食品和药物管理局(Food and Drug Administration, FDA)批准上市.

2.2.1 Rapa作用机制: Rapa化学结构与同类免疫抑制剂FK506相似. 其结构特征是环内有1个共轭三烯, 为白色固体结晶, 熔点为183 ℃-185 ℃, 亲脂性, 可溶解于甲醇、乙醇、丙酮和氯仿等有机溶剂, 极微溶于水, 几乎不溶于乙醚. 二者均需与免疫亲和蛋白结合而发挥作用, 在细胞内Rapa和FK506结合蛋白(FK506 binding protein, FKBP)结合, 形成免疫抑制复合物. 与FK506不同的是, Rapa与FKBP结合形成的复合物对钙调磷酸酶活性物无影响, 而是作用于mTOR, 与mTOR结合并抑制其活性. 抑制T细胞增殖周期中G1期向S期转变, 抑制细胞增殖和迁移, 从而防治急性排斥反应[24]. 由于Rapa还可以抑制生长因子及血管内皮细胞的增殖, 其也可以用于预防慢性排斥反应的发生. 当mTOR活性被Rapa抑制时, 调节性T细胞大量增殖, 增加了对机体免疫反应的负向调节[25]. Rapa除了对免疫细胞的作用外, 他也能抑制天然的和血小板衍生的生长因子激发的平滑肌细胞增生[26].

2.2.2 Rapa的临床应用: Rapa广泛应用于器官移植术后排斥反应治疗中, 包括抑制皮肤、心脏、肾脏、肝脏等器官移植后的排斥反应[27-29]. 尤其是对临床肝、肾移植患者应用FK506或环孢素A等治疗后, 转换成使用Rapa治疗能减轻其他免疫抑制药物引起的肾脏毒性.

2.2.3 Rapa对胰岛的毒性: 然而多项研究显示, Rapa在通过免疫抑制作用延长胰岛移植物存活的同时也对胰岛本身产生毒性. Rapa对胰岛直接的损伤主要表现在三方面: (1)他能直接抑制胰岛β细胞分泌胰岛素; (2)他能抑制胰岛细胞活力, 促进胰岛细胞凋亡; (3)他能抑制胰岛细胞的增殖.

在动物体内研究中, Fabian等[30]应用Rapa处理同种异体胰岛移植的小鼠7 d后, 发现小鼠血糖升明显高、胰岛素分泌减少的症状. 同样在大鼠胰岛移植中, Yang等[31]将Rapa浓度提高至0.5-5.0 mg/kg. 大鼠3 wk后分泌的胰胰岛明显减少. Whiting等[32]使用1.5 mg/(kg•d)的Rapa处理大鼠, 在13 d检测时发现血糖和尿糖明显升高. 在体外实验中, Fuhrer等[33]用Rapa处理30 min后发现细胞上清液中的胰岛素分泌大大减少. Barlow等[34]发现Rapa处理小鼠胰岛素瘤细胞48 h后, 胰岛素水平明显低于正常对照组. Marcelli-Tourvieille等[35]将人胰岛细胞在Rapa处理下培养5 d后, 发现胰岛素水平大幅度降低.

Fraenkel等[36]在大鼠移植16 d后观察药物对胰岛细胞凋亡的影响, 发现Rapa能促进胰岛细胞的凋亡. Barlow等[34]在研究小鼠MIN6细胞时发现, Rapa刺激细胞24 h已经能观察到胰岛细胞发生凋亡. Bell等[37]也证实Rapa在体外实验中能促进胰岛细胞的凋亡, 他们将人胰岛细胞培养4 d后发现当Rapa浓度增加至100 nmol/L时, 人胰岛细胞的活性被明显抑制.

Bussiere等[38]证实了Rapa能抑制胰岛细胞的增殖. 在小鼠体内实验中, Niclauss等[39]和Zahr等[40]分别证实Rapa刺激组能明显抑制胰岛细胞的增殖.

在Rapa对胰岛细胞产生毒性的机制中, 大多研究显示主要是mTORC1通路在起主导作用, 然而, 随着近年来mTORC2逐渐被大家所认识, 科学家们发现mTORC2在其中也发挥了重要作用.

Eve又记为SDZ RAD, 为Rapa的40-O-2-(羟乙基)衍生物. 他是一种半合成的Rapa衍生物, 其可溶性明显强于Rapa. 他由瑞士诺华公司(Novartis)最先研制. 其分子式C53H83NO14, 分子量958, 他是最早开始临床试验的Rapa衍生物之一. 该药2009-03-30通过FDA的快速审批, 用于晚期肾癌患者的治疗.

Eve的作用机制与Rapa类似, 都是通过抑制mTOR发挥其生物活性. 他能控制细胞周期、细胞大小、翻译起始和转录, 有良好的抗肿瘤作用[41]. Eve能与黏合蛋白FKBP-12形成高亲和性的复合物, 该复合物能与mTOR结合并抑制其信号肽, 使之减弱对下游底物的磷酸化作用, 从而阻断下游信号通路. Eve通过对mTOR的功能阻断, 抑制细胞由G1期(DNA合成前期)至S期(DNA合成期)的进程, 抑制细胞的增殖和分化, 从而预防排斥反应. Eve在器官移植上应用较多见, 已经应用于肾[42-45]、心[46-48]、肝[49-53]、肺[54]、胰岛移植[55,56].

Eve作为一种新型免疫抑制剂, 他增加了免疫抑制方案的选择性. 但是在多项肿瘤临床研究发现, Eve在抗肿瘤作用的时候也伴随着高血糖的症状. Doi等[57]和在胃癌治疗过程中使用Eve时发现高血糖的发生率增加至4%. Yoon等[58]也发现此现象, 在他们的研究中发现高血糖发生升高至20%. 在乳腺癌[59]的治疗过程中, 服用Eve后高血糖症状的发生率增加至13%. Yee等[60]在恶性血液病中使用Eve, 高血糖的发生率竟然达到22%.

Def是Rapa的C40位衍生物. 他是由CADD设计得到的半合成衍生物[61], 具有抑制mTOR的活性.

Def已被FDA以快速通道方式, 批准用于治疗软组织与骨肉瘤. 现已完成治疗血液系统疾病(白血病和淋巴瘤)的二期临床, 目前已完成头颈部鳞状细胞癌Ⅰ期临床试验[62], 也已经完成子宫内膜癌的Ⅱ期临床试验[63]. 该药物目前也仅应用于肿瘤实验和临床研究, 还没有用于器官移植研究的相关文献报道.

Zot是由Abott及Medtronic公司研发的一种Rapa衍生物. 他是Rapa的C40位四唑取代物. 研究表明其具有抗增殖活性. 他与Rapa相比具有体内半衰期短的特点. Zot的作用机制与Rapa类似, 都是通过与FKBP12结合形成复合物, 该复合物再与mTOR蛋白激酶结合形成三聚体, 抑制mTOR的活性, 阻止其磷酸化, 使细胞周期无法从G1期进入S期.

Zot在临床研究中多用于药物涂层支架. 研究[64]证明他能有效的预防冠状动脉治愈后再狭窄的效果, 而且目前绝大多数该药物研究都集中在支架涂层上. FDA已经批准了Zot为涂层药物的endeavor洗脱支架系统用于治疗冠状动脉疾病. Zot的亲脂性是Rapa的2.2倍, 高亲脂性使得他更容易通过血管细胞壁进入组织细胞内, 进一步提高了药物在组织内停留的时间, 使其具有更好的临床疗效. 但是有文献报道[65]其用于支架涂层可能会促进血栓形成. 移植方面Chen等[64]报道Zot在移植方面的作用, 他们发现能够延长大鼠同种心脏移植存活(不是真正的心脏移植, 而是新生大鼠心脏取部分移植于受体耳后, 对照组14 d后移植物被吸收, 所以所有实验在14 d取移植物看是否可以看得见并且用电刺激看其能否产生电生理反应), 同时Zot还能抑制混合淋巴细胞培养反应和淋巴细胞转化T细胞增殖. 目前并未见Zot在器官移植的基础研究及临床研究的其他报道.

Rapa作为一种免疫抑制剂给维持胰岛移植物的存活带来显著帮助, 但是其也对胰岛本身造成直接损伤. 他能抑制胰岛细胞的增殖; 在一定程度上促进胰岛细胞的凋亡; 并能直接损害胰岛细胞的功能, 减少胰岛素的分泌. 文中所提的Rapa衍生物作为新型药物, 目前主要应用于抗肿瘤治疗, Eve还应用于器官移植排斥反应的防治. Def和Zot迄今为止, 未见在器官移植领域有研究报道, 但他们作为Rapa的衍生物, 是有潜力的抗排斥药物. 而这四种衍生物对胰岛是否同样具有毒性, 目前鲜有研究. 他们是否是胰岛移植的合适用药尚需进一步的研究, 而其中的具体机制也有待进一步的探索.

胰岛移植是治疗Ⅰ型糖尿病的有效手段. Edmonton方案的出现, 使胰岛移植的研究和应用迎来了一个新的高潮. 然而研究中发现Edmonton方案中推荐的用于抗免疫排斥的药物雷帕霉素会抑制胰岛素的分泌. 雷帕霉素的衍生物也是有潜力的抗免疫排斥药物, 他们对胰岛的毒性究竟如何, 至今少有详细阐述.

高凌, 副教授, 副主任医师, 武汉大学人民医院内分泌科

自2000年公布Edmonton方案以来, 胰岛移植以及胰岛移植中的免疫抑制方案就成为了人们关注的热点. 雷帕霉素作为Edmonton方案中的推荐用药, 一直是研究者们最为关注的免疫抑制剂之一. 雷帕霉素衍生物也同样具有免疫抑制活性, 目前广泛用于抗移植排斥、抗肿瘤和药物洗脱支架的研究.

有研究显示, 雷帕霉素对小鼠胰岛素瘤细胞系和人胰岛均有毒性. 也有临床报道, 在临床使用依维莫司抗肿瘤的过程中出现了高血糖现象.

自从雷帕霉素及其衍生物被广泛研究和应用开始, 就有报导他们诱导高血糖的现象和对胰岛的毒性. 本文对他们的胰岛毒性作用做一总结.

总结雷帕霉素及其衍生物对胰岛的毒性, 有助于指导他们在抗肿瘤和抗排斥治疗等应用中的临床用药.

Edmonton方案: 2000年Shapiro等报告了被称为"Edmonton方案"的胰岛移植方案, 总结了胰岛的分离、纯化和移植办法, 提倡使用不含激素的低剂量免疫抑制方案即雷帕霉素和他克莫司.

雷帕霉素是胰岛移植时重要的免疫抑制剂. 本文探讨雷帕霉素的衍生物(依维莫司、地磷莫司、佐他莫司、替西罗莫司)的免疫抑制作用、抗肿瘤作用, 以及对胰岛的毒性作用作一综述, 具有一定的临床意义和先进性.

编辑: 于明茜 电编:都珍珍

| 1. | Shapiro AM, Lakey JR, Ryan EA, Korbutt GS, Toth E, Warnock GL, Kneteman NM, Rajotte RV. Islet transplantation in seven patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus using a glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:230-238. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 2. | Shapiro AM, Ricordi C, Hering BJ, Auchincloss H, Lindblad R, Robertson RP, Secchi A, Brendel MD, Berney T, Brennan DC. International trial of the Edmonton protocol for islet transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1318-1330. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 3. | Hering BJ, Kandaswamy R, Ansite JD, Eckman PM, Nakano M, Sawada T, Matsumoto I, Ihm SH, Zhang HJ, Parkey J. Single-donor, marginal-dose islet transplantation in patients with type 1 diabetes. JAMA. 2005;293:830-835. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 4. | Froud T, Ricordi C, Baidal DA, Hafiz MM, Ponte G, Cure P, Pileggi A, Poggioli R, Ichii H, Khan A. Islet transplantation in type 1 diabetes mellitus using cultured islets and steroid-free immunosuppression: Miami experience. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:2037-2046. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 5. | Matsumoto S, Okitsu T, Iwanaga Y, Noguchi H, Nagata H, Yonekawa Y, Yamada Y, Fukuda K, Tsukiyama K, Suzuki H. Insulin independence after living-donor distal pancreatectomy and islet allotransplantation. Lancet. 2005;365:1642-1644. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 6. | Lacy PE, Kostianovsky M. Method for the isolation of intact islets of Langerhans from the rat pancreas. Diabetes. 1967;16:35-39. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 7. | Tzakis AG, Ricordi C, Alejandro R, Zeng Y, Fung JJ, Todo S, Demetris AJ, Mintz DH, Starzl TE. Pancreatic islet transplantation after upper abdominal exenteration and liver replacement. Lancet. 1990;336:402-405. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 8. | Ryan EA, Paty BW, Senior PA, Bigam D, Alfadhli E, Kneteman NM, Lakey JR, Shapiro AM. Five-year follow-up after clinical islet transplantation. Diabetes. 2005;54:2060-2069. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 9. | Law BK. Rapamycin: an anti-cancer immunosuppressant? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;56:47-60. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 10. | Mathew T, Kreis H, Friend P. Two-year incidence of malignancy in sirolimus-treated renal transplant recipients: results from five multicenter studies. Clin Transplant. 2004;18:446-449. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 11. | Kauffman HM, Cherikh WS, Cheng Y, Hanto DW, Kahan BD. Maintenance immunosuppression with target-of-rapamycin inhibitors is associated with a reduced incidence of de novo malignancies. Transplantation. 2005;80:883-889. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 12. | Yakupoglu YK, Buell JF, Woodle S, Kahan BD. Individualization of immunosuppressive therapy. III. Sirolimus associated with a reduced incidence of malignancy. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:358-361. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 13. | Campistol JM, Eris J, Oberbauer R, Friend P, Hutchison B, Morales JM, Claesson K, Stallone G, Russ G, Rostaing L. Sirolimus therapy after early cyclosporine withdrawal reduces the risk for cancer in adult renal transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:581-589. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 14. | Schena FP, Pascoe MD, Alberu J, del Carmen Rial M, Oberbauer R, Brennan DC, Campistol JM, Racusen L, Polinsky MS, Goldberg-Alberts R. Conversion from calcineurin inhibitors to sirolimus maintenance therapy in renal allograft recipients: 24-month efficacy and safety results from the CONVERT trial. Transplantation. 2009;87:233-242. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 15. | Heitman J, Movva NR, Hall MN. Targets for cell cycle arrest by the immunosuppressant rapamycin in yeast. Science. 1991;253:905-909. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 16. | Gangloff YG, Mueller M, Dann SG, Svoboda P, Sticker M, Spetz JF, Um SH, Brown EJ, Cereghini S, Thomas G. Disruption of the mouse mTOR gene leads to early postimplantation lethality and prohibits embryonic stem cell development. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9508-9516. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 17. | Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274-293. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 18. | Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Kim DH, Guertin DA, Latek RR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM. Rictor, a novel binding partner of mTOR, defines a rapamycin-insensitive and raptor-independent pathway that regulates the cytoskeleton. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1296-1302. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 19. | Pearce LR, Sommer EM, Sakamoto K, Wullschleger S, Alessi DR. Protor-1 is required for efficient mTORC2-mediated activation of SGK1 in the kidney. Biochem J. 2011;436:169-179. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 20. | Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sengupta S, Sheen JH, Hsu PP, Bagley AF, Markhard AL, Sabatini DM. Prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB. Mol Cell. 2006;22:159-168. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 21. | Powell JD, Pollizzi KN, Heikamp EB, Horton MR. Regulation of immune responses by mTOR. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:39-68. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 22. | Araki K, Youngblood B, Ahmed R. The role of mTOR in memory CD8 T-cell differentiation. Immunol Rev. 2010;235:234-243. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 23. | Vézina C, Kudelski A, Sehgal SN. Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. I. Taxonomy of the producing streptomycete and isolation of the active principle. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 1975;28:721-726. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 24. | Terada N, Lucas JJ, Szepesi A, Franklin RA, Domenico J, Gelfand EW. Rapamycin blocks cell cycle progression of activated T cells prior to events characteristic of the middle to late G1 phase of the cycle. J Cell Physiol. 1993;154:7-15. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 25. | Waickman AT, Powell JD. mTOR, metabolism, and the regulation of T-cell differentiation and function. Immunol Rev. 2012;249:43-58. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 26. | Gregory CR, Pratt RE, Huie P, Shorthouse R, Dzau VJ, Billingham ME, Morris RE. Effects of treatment with cyclosporine, FK 506, rapamycin, mycophenolic acid, or deoxyspergualin on vascular muscle proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Transplant Proc. 1993;25:770-771. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Euvrard S, Ulrich C, Lefrancois N. Immunosuppressants and skin cancer in transplant patients: focus on rapamycin. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:628-633. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 28. | Edelman ER, Danenberg HD. Rapamycin for cardiac transplant rejection and vasculopathy: one stone, two birds? Circulation. 2003;108:6-8. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 29. | Hamashima T, Yoshimura N, Ohsaka Y, Oka T, Stepkowski SM, Kahan BD. In vivo use of rapamycin suppresses neither IL-2 production nor IL-2 receptor expression in rat transplant model. Transplant Proc. 1993;25:723-724. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Fabian MC, Lakey JR, Rajotte RV, Kneteman NM. The efficacy and toxicity of rapamycin in murine islet transplantation. In vitro and in vivo studies. Transplantation. 1993;56:1137-1142. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 31. | Yang SB, Lee HY, Young DM, Tien AC, Rowson-Baldwin A, Shu YY, Jan YN, Jan LY. Rapamycin induces glucose intolerance in mice by reducing islet mass, insulin content, and insulin sensitivity. J Mol Med (Berl). 2012;90:575-585. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 32. | Whiting PH, Woo J, Adam BJ, Hasan NU, Davidson RJ, Thomson AW. Toxicity of rapamycin--a comparative and combination study with cyclosporine at immunotherapeutic dosage in the rat. Transplantation. 1991;52:203-208. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 33. | Fuhrer DK, Kobayashi M, Jiang H. Insulin release and suppression by tacrolimus, rapamycin and cyclosporin A are through regulation of the ATP-sensitive potassium channel. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2001;3:393-402. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 34. | Barlow AD, Xie J, Moore CE, Campbell SC, Shaw JA, Nicholson ML, Herbert TP. Rapamycin toxicity in MIN6 cells and rat and human islets is mediated by the inhibition of mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2). Diabetologia. 2012;55:1355-1365. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 35. | Marcelli-Tourvieille S, Hubert T, Moerman E, Gmyr V, Kerr-Conte J, Nunes B, Dherbomez M, Vandewalle B, Pattou F, Vantyghem MC. In vivo and in vitro effect of sirolimus on insulin secretion. Transplantation. 2007;83:532-538. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 36. | Fraenkel M, Ketzinel-Gilad M, Ariav Y, Pappo O, Karaca M, Castel J, Berthault MF, Magnan C, Cerasi E, Kaiser N. mTOR inhibition by rapamycin prevents beta-cell adaptation to hyperglycemia and exacerbates the metabolic state in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2008;57:945-957. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 37. | Bell E, Cao X, Moibi JA, Greene SR, Young R, Trucco M, Gao Z, Matschinsky FM, Deng S, Markman JF. Rapamycin has a deleterious effect on MIN-6 cells and rat and human islets. Diabetes. 2003;52:2731-2739. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Bussiere CT, Lakey JR, Shapiro AM, Korbutt GS. The impact of the mTOR inhibitor sirolimus on the proliferation and function of pancreatic islets and ductal cells. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2341-2349. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 39. | Niclauss N, Bosco D, Morel P, Giovannoni L, Berney T, Parnaud G. Rapamycin impairs proliferation of transplanted islet β cells. Transplantation. 2011;91:714-722. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 40. | Zahr E, Molano RD, Pileggi A, Ichii H, Jose SS, Bocca N, An W, Gonzalez-Quintana J, Fraker C, Ricordi C. Rapamycin impairs in vivo proliferation of islet beta-cells. Transplantation. 2007;84:1576-1583. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 41. | Kovarik JM. Everolimus: a proliferation signal inhibitor targeting primary causes of allograft dysfunction. Drugs Today (Barc). 2004;40:101-109. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 42. | Campistol JM, de Fijter JW, Nashan B, Holdaas H, Vítko S, Legendre C. Everolimus and long-term outcomes in renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2011;92:S3-26. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 43. | Chan L, Greenstein S, Hardy MA, Hartmann E, Bunnapradist S, Cibrik D, Shaw LM, Munir L, Ulbricht B, Cooper M. Multicenter, randomized study of the use of everolimus with tacrolimus after renal transplantation demonstrates its effectiveness. Transplantation. 2008;85:821-826. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 44. | Cibrik D, Arcona S, Vasquez E, Baillie GM, Irish W. Long-term experience with everolimus in kidney transplantation in the United States. Transplant Proc. 2011;43:2562-2567. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 45. | Cibrik D, Silva HT, Vathsala A, Lackova E, Cornu-Artis C, Walker RG, Wang Z, Zibari GB, Shihab F, Kim YS. Randomized trial of everolimus-facilitated calcineurin inhibitor minimization over 24 months in renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2013;95:933-942. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 46. | Certican (Everolimus) in heart transplantation: from clinical trial to clinical experience. Proceedings of a meeting, Vienna, Austria, September 9, 2004. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:S183-S211. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Behnke-Hall K, Bauer J, Thul J, Akintuerk H, Reitz K, Bauer A, Schranz D. Renal function in children with heart transplantation after switching to CNI-free immunosuppression with everolimus. Pediatr Transplant. 2011;15:784-789. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 48. | Bocchi EA, Ahualli L, Amuchastegui M, Boullon F, Cerutti B, Colque R, Fernandez D, Fiorelli A, Olaya P, Vulcado N. Recommendations for use of everolimus after heart transplantation: results from a Latin-American Consensus Meeting. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:937-942. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 49. | Alegre C, Jiménez C, Manrique A, Abradelo M, Calvo J, Loinaz C, García-Sesma A, Cambra F, Alvaro E, García M. Everolimus monotherapy or combined therapy in liver transplantation: indications and results. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:1971-1974. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 50. | Bilbao I, Sapisochin G, Dopazo C, Lazaro JL, Pou L, Castells L, Caralt M, Blanco L, Gantxegi A, Margarit C. Indications and management of everolimus after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:2172-2176. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 51. | Casanovas T, Argudo A, Peña-Cala MC. Everolimus in clinical practice in long-term liver transplantation: an observational study. Transplant Proc. 2011;43:2216-2219. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 52. | De Simone P, Beckebaum S, Koneru B, Fung J, Saliba F. Everolimus with reduced tacrolimus in liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:1373-1374. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 53. | De Simone P, Carrai P, Precisi A, Petruccelli S, Baldoni L, Balzano E, Ducci J, Caneschi F, Coletti L, Campani D. Conversion to everolimus monotherapy in maintenance liver transplantation: feasibility, safety, and impact on renal function. Transpl Int. 2009;22:279-286. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 54. | de Pablo A, Santos F, Solé A, Borro JM, Cifrian JM, Laporta R, Monforte V, Román A, de la Torre M, Ussetti P. Recommendations on the use of everolimus in lung transplantation. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2013;27:9-16. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 55. | di Francesco F, Cautero N, Vincenzi P, Nicolini D, De Luca S, Vecchi A, Garelli P, Martorelli G, Gentili M, Risaliti A. One year follow-up of steroid-free immunosuppression plus everolimus in isolated pancreas transplantation. Transplantation. 2008;86:1146-1147. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 56. | Sato E, Yano I, Shimomura M, Masuda S, Katsura T, Matsumoto S, Okitsu T, Iwanaga Y, Uemoto S, Inui K. Larger dosage required for everolimus than sirolimus to maintain same blood concentration in two pancreatic islet transplant patients with tacrolimus. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2009;24:175-179. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 57. | Doi T, Muro K, Boku N, Yamada Y, Nishina T, Takiuchi H, Komatsu Y, Hamamoto Y, Ohno N, Fujita Y. Multicenter phase II study of everolimus in patients with previously treated metastatic gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1904-1910. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 58. | Yoon DH, Ryu MH, Park YS, Lee HJ, Lee C, Ryoo BY, Lee JL, Chang HM, Kim TW, Kang YK. Phase II study of everolimus with biomarker exploration in patients with advanced gastric cancer refractory to chemotherapy including fluoropyrimidine and platinum. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1039-1044. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 59. | Baselga J, Campone M, Piccart M, Burris HA, Rugo HS, Sahmoud T, Noguchi S, Gnant M, Pritchard KI, Lebrun F. Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:520-529. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 60. | Yee KW, Zeng Z, Konopleva M, Verstovsek S, Ravandi F, Ferrajoli A, Thomas D, Wierda W, Apostolidou E, Albitar M. Phase I/II study of the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus (RAD001) in patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5165-5173. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 61. | Sessa C, Tosi D, Viganò L, Albanell J, Hess D, Maur M, Cresta S, Locatelli A, Angst R, Rojo F. Phase Ib study of weekly mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor ridaforolimus (AP23573; MK-8669) with weekly paclitaxel. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1315-1322. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 62. | Piha-Paul SA, Munster PN, Hollebecque A, Argilés G, Dajani O, Cheng JD, Wang R, Swift A, Tosolini A, Gupta S. Results of a phase 1 trial combining ridaforolimus and MK-0752 in patients with advanced solid tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:1865-1873. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 63. | Oza AM, Pignata S, Poveda A, McCormack M, Clamp A, Schwartz B, Cheng J, Li X, Campbell K, Dodion P. Randomized Phase II Trial of Ridaforolimus in Advanced Endometrial Carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3576-3582. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 64. | Chen YW, Smith ML, Sheets M, Ballaron S, Trevillyan JM, Burke SE, Rosenberg T, Henry C, Wagner R, Bauch J. Zotarolimus, a novel sirolimus analogue with potent anti-proliferative activity on coronary smooth muscle cells and reduced potential for systemic immunosuppression. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2007;49:228-235. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 65. | Camici GG, Steffel J, Amanovic I, Breitenstein A, Baldinger J, Keller S, Lüscher TF, Tanner FC. Rapamycin promotes arterial thrombosis in vivo: implications for everolimus and zotarolimus eluting stents. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:236-242. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 66. | Fazio N, Dettori M, Lorizzo K. Temsirolimus for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1050; author reply 1050-1051. [PubMed] |

| 67. | Ferretti G. Temsirolimus for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1050; author reply 1050-1051. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 68. | Figlin RA. Temsirolimus for advanced renal cell carcinoma. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2007;5:893. [PubMed] |

| 69. | Atkins MB, Hidalgo M, Stadler WM, Logan TF, Dutcher JP, Hudes GR, Park Y, Liou SH, Marshall B, Boni JP. Randomized phase II study of multiple dose levels of CCI-779, a novel mammalian target of rapamycin kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced refractory renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:909-918. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 70. | Chan S, Scheulen ME, Johnston S, Mross K, Cardoso F, Dittrich C, Eiermann W, Hess D, Morant R, Semiglazov V. Phase II study of temsirolimus (CCI-779), a novel inhibitor of mTOR, in heavily pretreated patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5314-5322. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 71. | Chang SM, Kuhn J, Wen P, Greenberg H, Schiff D, Conrad C, Fink K, Robins HI, Cloughesy T, De Angelis L. Phase I/pharmacokinetic study of CCI-779 in patients with recurrent malignant glioma on enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs. Invest New Drugs. 2004;22:427-435. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 72. | Chang SM, Wen P, Cloughesy T, Greenberg H, Schiff D, Conrad C, Fink K, Robins HI, De Angelis L, Raizer J. Phase II study of CCI-779 in patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Invest New Drugs. 2005;23:357-361. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 73. | Hui IC, Tung EK, Sze KM, Ching YP, Ng IO. Rapamycin and CCI-779 inhibit the mammalian target of rapamycin signalling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2010;30:65-75. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 74. | Li S, Liang Y, Wu M, Wang X, Fu H, Chen Y, Wang Z. The novel mTOR inhibitor CCI-779 (temsirolimus) induces antiproliferative effects through inhibition of mTOR in Bel-7402 liver cancer cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2013;13:30. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 75. | Pandya KJ, Dahlberg S, Hidalgo M, Cohen RB, Lee MW, Schiller JH, Johnson DH. A randomized, phase II trial of two dose levels of temsirolimus (CCI-779) in patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer who have responding or stable disease after induction chemotherapy: a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (E1500). J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:1036-1041. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 76. | Witzens-Harig M, Memmer ML, Dreyling M, Hess G. A phase I/II trial to evaluate the safety, feasibility and activity of salvage therapy consisting of the mTOR inhibitor Temsirolimus added to standard therapy of Rituximab and DHAP for the treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large cell B-Cell lymphoma - the STORM trial. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:308. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 77. | Thallinger C, Poeppl W, Pratscher B, Mayerhofer M, Valent P, Tappeiner G, Joukhadar C. CCI-779 plus cisplatin is highly effective against human melanoma in a SCID mouse xenotranplantation model. Pharmacology. 2007;79:207-213. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 78. | Pachow D, Andrae N, Kliese N, Angenstein F, Stork O, Wilisch-Neumann A, Kirches E, Mawrin C. mTORC1 inhibitors suppress meningioma growth in mouse models. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:1180-1189. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 79. | Thallinger C, Werzowa J, Poeppl W, Kovar FM, Pratscher B, Valent P, Quehenberger P, Joukhadar C. Comparison of a treatment strategy combining CCI-779 plus DTIC versus DTIC monotreatment in human melanoma in SCID mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2411-2417. [PubMed] [DOI] |