修回日期: 2012-12-20

接受日期: 2012-12-28

在线出版日期: 2013-01-08

目的: 观察阿司匹林对人结肠癌肿瘤干细胞标志物CD133表达的影响, 探讨其对结肠癌干细胞的作用.

方法: 流式细胞仪检测结肠癌细胞株HT-29和SW480在不同浓度阿司匹林(0、2.5、5.0、10.0 mmol/L)作用下CD133的表达变化.

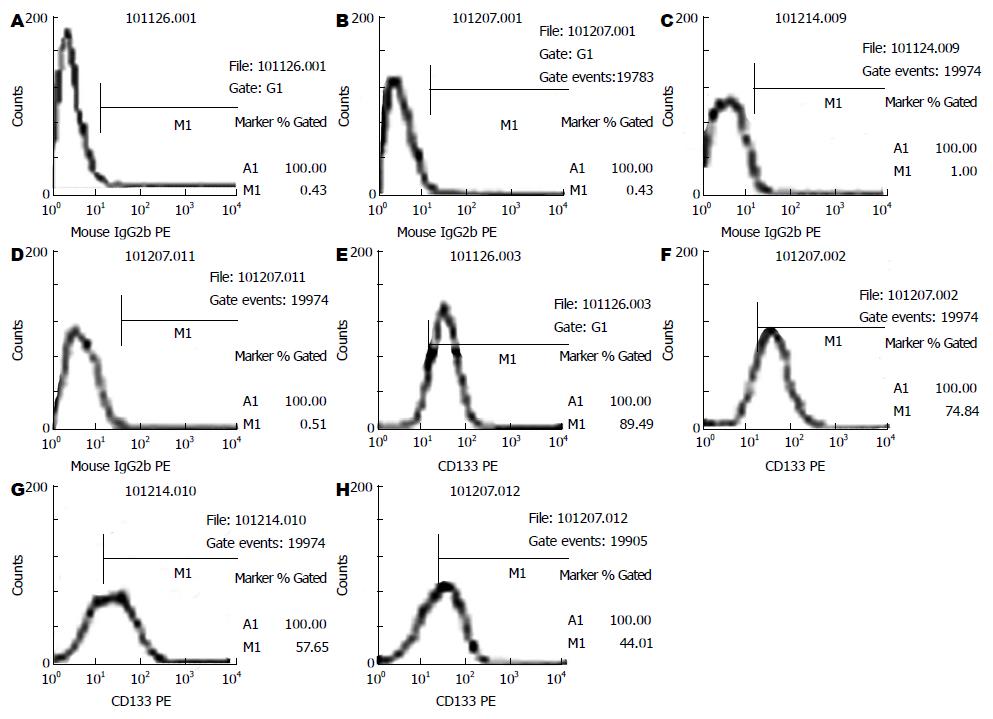

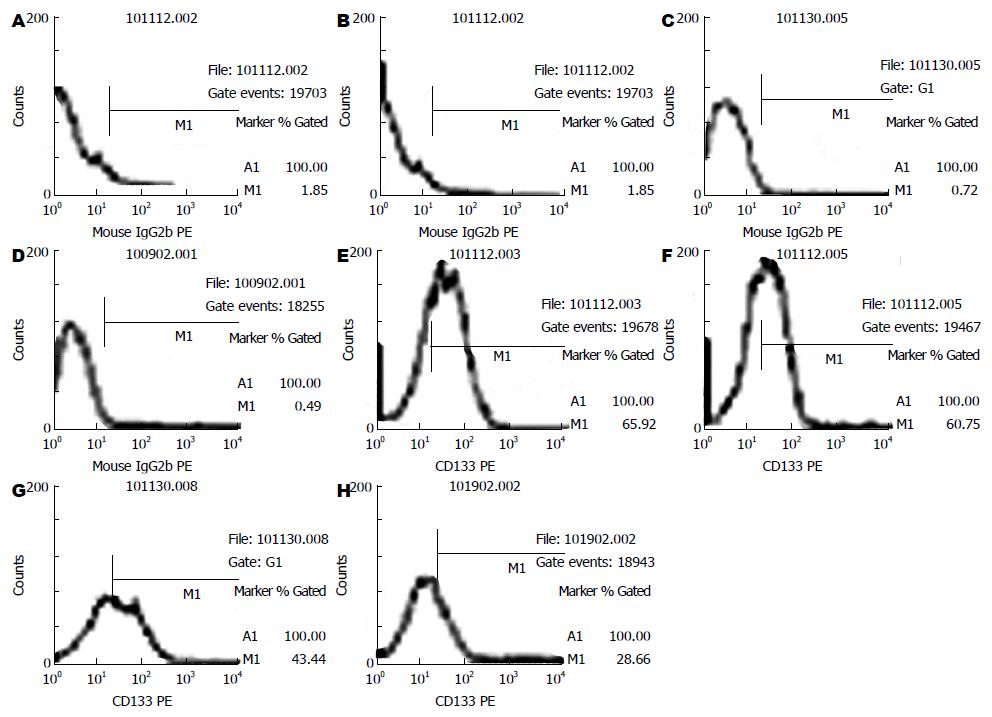

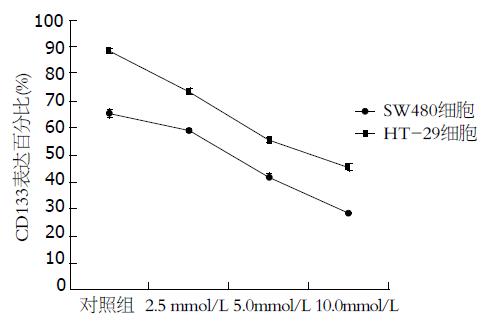

结果: 流式细胞仪检测结果显示CD133+细胞在HT-29细胞株中的比例为88.37%±1.00%, 在SW480细胞系中的比例为65.22%±1.50%. 用阿司匹林干预后, 随着阿司匹林浓度的增加, CD133在结肠癌细胞系HT-29和SW480中的表达呈下降趋势, 差异有统计学意义(45.41±1.09, 55.31±1.07 vs 73.45±1.04; 28.28±0.30, 42.27±0.78 vs 58.96±0.09, 均P<0.05).

结论: 阿司匹林能抑制结肠癌细胞株HT-29和SW480中CD133的表达, 呈剂量依赖性.

引文著录: 陈小燕, 廖永美, 刘胜远, 赵逵. 阿司匹林对HT-29、SW480结肠癌细胞株CD133表达的影响. 世界华人消化杂志 2013; 21(1): 13-18

Revised: December 20, 2012

Accepted: December 28, 2012

Published online: January 8, 2013

AIM: To investigate the effect of treatment with aspirin on CD133 protein expression in colorectal cancer cell (CRC) lines.

METHODS: HT-29 and SW480 cells were treated with different concentrations of aspirin (0.0, 2.5, 5.0, or 10.0 mmol/L), and the expression of CD133 was detected by flow cytometry.

RESULTS: Flow cytometry results demonstrated that the proportions of CD133+ cells were 88.37% ± 1.00% and 65.22% ± 1.52% in HT-29 and SW480 cells, respectively. Treatment with aspirin significantly reduced the expression of CD133 in HT-29 and SW480 cells in a concentration-dependent manner (both P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION: Treatment with aspirin can inhibit the expression of CD133 in HT-29 and SW480 cells in a concentration-dependent manner.

- Citation: Chen XY, Liao YM, Liu SY, Zhao K. Treatment with aspirin inhibits the expression of CD133 in human colorectal cancer cells HT-29 and SW480. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2013; 21(1): 13-18

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v21/i1/13.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v21.i1.13

近年来, 肿瘤干细胞(cancer stem cells, CSCs)概念[1,2]的提出更好地解释了放、化疗与生物免疫治疗等方法能够杀灭大部分肿瘤细胞而无法从根本上治愈结直肠癌的问题, 并为研究肿瘤细胞的生物学特性提供了新的方向和思路以及为肿瘤的临床治疗提供了新的靶点, 目前已逐渐成为肿瘤防治研究的新热点. CD133是CSCs标志物之一[3], 在多种实体肿瘤中表达, 包括结直肠癌、脑胶质瘤等[4,5]. CD133+细胞比例与肿瘤的侵袭性、病理分级及临床预后密切相关[6], 可能成为潜在的治疗靶点. 阿司匹林作为一种临床常用的非甾体抗炎药(non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, NSAIDs), 除具有解热镇痛抗炎作用外, 还可以降低腺瘤和结直肠癌发生的风险[7,8], 有效预防结直肠癌发生[9], 甚至可以降低患者的死亡率以及改善生存质量[7], 尤其是在最初的5年[8]. 然而阿司匹林是如何作用于结直肠癌干细胞, 对CSCs标志物CD133又有何影响, 都尚不清楚. 本研究拟通过对不同浓度的阿司匹林对人结肠癌细胞株HT-29、SW480中CSCs标志物CD133表达的影响进行研究, 以探讨其对结直肠癌干细胞是否有潜在的影响.

人结肠癌细胞株HT-29、SW480分别购自中科院上海细胞库、重庆医科大学细胞实验室; 阿司匹林、McCoy'S 5a培养基及胰蛋白酶购自美国Sigma公司; 胎牛血清购自美国Hyclone公司; 小鼠抗人CD133单克隆抗体、同型抗体mouse IgG2a-PE购自德国Miltenyi-Biotec公司; 流式细胞仪为美国BD公司产品.

1.2.1 细胞的培养: 人结肠癌细胞株HT-29、SW480培养于含10%胎牛血清的McCoy'S 5a培养基, 置于37 ℃、50 mL/L CO2的培养箱中常规培养, 待细胞贴壁生长至80%-90%融合时, 用0.25%胰蛋白酶与0.02% EDTA混合液进行消化传代. 细胞生长状态良好、处于对数期时用于实验.

1.2.2 流式细胞仪直接免疫荧光法检测在不同浓度阿司匹林作用下CDl33的表达: 取对数生长期的结肠癌细胞株HT-29、SW480, 用0.25%胰蛋白酶-0.02%EDTA混合液进行消化, 离心计数, 用McCoy'S 5a完全培养液稀释至5×104个/mL的单细胞悬液, 接种于50 mL细胞培养瓶中培养, 待细胞培养24 h后, 换用无血清培养基进行同步化培养. 同步化培养24 h后按分组加药: 0、2.5、5.0、10.0 mmol/L, HT-29细胞再继续培养48 h、SW480细胞再继续培养72 h后, 用0.25%胰蛋白酶与0.02% EDTA混合液进行消化制成单细胞悬液, 离心计数, PBS洗涤1次, 离心300 g, 10 min, 去上清, 调整浓度为1×107个/mL, 每管加入100 μL单细胞悬液, 加入PE标记的小鼠抗人CD133单克隆抗体10 μL, 同时在对照细胞中添加相应的同型对照Mouse IgG2a-PE 10 μL, 避光, 4 ℃. 放置30 min, PBS洗2次, 除去未结合一抗, 离心300 g, 10 min, 去除上清液体, 各管加入500 μL PBS重悬; 标记好的细胞悬液经200目筛网滤过, 上流式细胞仪分析.

统计学处理 计量资料均采用mean±SD表示, 采用SPSS17.0统计学软件进行统计学处理, 组内的比较采用单因素方差分析, 组间比较采用独立样本t检验, P<0.05表示差异有统计学意义.

流式细胞仪检测结肠癌细胞株HT-29和SW480细胞中CD133+细胞在不同药物组的百分率比较结果显示(表1, 图1-3), CD133在结肠癌细胞株HT-29和SW480中大量表达, CD133+细胞在上述两种细胞系中的比例分别为88.37%±1.00%, 65.22%±1.52%. 用阿司匹林干预后, 随着药物浓度的增加, CD133+细胞在结肠癌细胞株HT-29和SW480细胞中的比例呈明显的下降趋势, 并具有良好的量-效关系, 与对照组相比, 差异有统计学意义(45.41±1.09, 55.31±1.07 vs 73.45±1.04; 28.28±0.30, 42.27±0.78 vs 58.96±0.09, 均P<0.05).

结直肠癌是胃肠道中最常见的恶性肿瘤之一, 居全球肿瘤发病率的第3位[10], 并且其治疗面临着多耐药性、高复发率等诸多挑战. 近年来, CSCs理论认为CSCs是肿瘤发生的根源, 也是彻底根治肿瘤的靶点[11], 因此为肿瘤研究和治疗提供了新的方向. CSCs是指存在于肿瘤组织内的一群数目极少但具有自我更新和增殖能力的细胞, 能够分化为不同表型的癌细胞, 在肿瘤的发生、发展和转归过程中发挥重要作用[1,12]. 迄今为止, 已经发现了大量与CSCs相关的表面标志物, 如CD133、Lgr5[13,14]、CD44[15]、CD166[16]、Bmi-1[17]及DCAMKL-1[18]等, 在这些标志中最引人关注的是CD133, 也是研究较多的CSCs标志物.

近年来研究发现, CD133可以作为结直肠癌干细胞鉴定的标志物. 尽管CD133已经用于分离包括结肠癌在内的各种CSCs, 但其功能目前还不是很清楚[19]. 有研究发现CD133的表达与结直肠癌患者的预后密切相关, Zhang等[4]对Ⅱ-Ⅲ期结肠癌患者CD133和CXCR4共表达的研究表明, CD133和CXCR4共表达是患者不良预后的危险因素, 同时指出CD133推动了癌症发展. Coco等[20]的研究也指出, CD133表达增高在结直肠癌中频繁发生, 其高表达预示着患者预后较差, 因此对CD133表达的评估可以帮助识别高危结肠癌患者. Horst等[21]还发现CD133与CD44、CD166相比而言, 是预测患者预后最好的指标. 研究表明, CD133+肿瘤细胞促进了肿瘤细胞的复发, 可能是由于CDl33+细胞能够逃避固有免疫和适应性免疫监视, 参与肿瘤血管的形成, 干细胞相关信号通路的激活, 并借助自分泌作用产生IL-4介导耐药[22]及阻止这些细胞凋亡[23], 其大量表达会导致化疗药物失效, 造成肿瘤的复发和转移[24]. 因此CD133可能成为结直肠癌治疗的一潜在靶点.

本研究结果显示, CD133+细胞在HT-29细胞株中的比例为88.37%±1.00%, 在SW480细胞株中的比例为65.22%±1.50%. Elsaba等[25]同样运用流式细胞仪检测8种结肠癌细胞株中CD133+细胞比例的结果显示, 其比例在0%-95%不等, 其中HT-29细胞中CD133+细胞比例最高, 大于95%, 而SW480细胞中CD133+细胞比例占40%左右的, 这与本研究结果大致相符. Kawamoto等[26]的研究显示, 结肠癌细胞株SW620含有CD133+和CD133-两种细胞表型, 而前者与CSCs的特性相一致. 由此表明, CD133可作为识别和鉴定结直肠癌干细胞的标志物. 此外研究表明, CD133+细胞比例与肿瘤的侵袭性、病理分级及临床预后密切相关. Lee等[27]研究发现, HT-29细胞中, CD133+细胞较CD133-细胞有更强的致瘤性, 并且上述两种细胞的蛋白表达是有差异的, 例如与肿瘤转移和浸润有关的肌动蛋白相关蛋白2/3复合体亚单位和肌动蛋白结合蛋白在CD133+细胞中表达上调, 其对肿瘤的发生和干细胞特性起重要作用.

大量的证据表明, 服用阿司匹林或其他NSAIDs可以减少患结直肠癌的危险、改善结直肠癌患者的预后以及降低术后复发率等. Fox等[28]研究发现每日服用阿司匹林可使其癌症死亡风险降低16%. 然而其对CSCs的作用机制尚不清楚, 对CSCs标志物CD133有何影响, 都有待进一步研究. 本研究初步显示, 不同药物浓度的阿司匹林能够有效抑制对体外培养的结肠癌细胞株HT-29和SW480细胞中CD133的表达, 并呈良好的剂量依赖关系, 对照组和药物组之间比较差异有统计学意义(P<0.05). 这和英国纽卡斯尔大学的研究相符, 其研究发现长期服用小剂量阿司匹林可使易引发结直肠癌的林奇综合征患者肠癌的发病率降低, 他们认为阿司匹林对结肠内的异常干细胞存活有影响. 同时Lou等[29]关于阿司匹林对内皮祖细胞生物学的研究也表明, 阿司匹林可以降低受试者外周血中CD133+内皮祖细胞的比例, 呈明显的时效关系, 但与量效关系不大. Mak等[30]的研究指出, 下调CD133导致β-catenin的乙酰化和降解的增加, 从而抑制肿瘤的生长增殖. 安敏等[31]研究也显示阿司匹林对结肠癌细胞株Caco-2的生长起抑制作用, 呈剂量-时间依赖性. Zhu等[32]发现内源性Wnt信号激活能破坏隐窝的结构并导致CD133+干细胞比例增加, 最终导致在小肠黏膜的恶性转化. 这一些结果均提示CD133+结肠癌干性细胞与Wnt信号通路之间的潜在联系. 因此, 我们推测阿司匹林对结肠癌CSCs的作用可能涉及到Wnt/β-catenin通路.

总之, 本研究结果表明CD133在人结肠癌HT-29和SW480细胞株中大量表达, 表明其可作为识别和鉴定结直肠癌干细胞的标志物和进行干预治疗的观察指标. 同时阿司匹林可减少CSCs标志物CD133的表达而抑制CSCs, 其机制可能涉及到Wnt/β-catenin通路, 为NSAIDs阿司匹林临床防治结直肠癌提供了新的相关实验依据. 然而阿司匹林抑制CD133的表达所涉及的具体机制仍需进一步研究.

肿瘤干细胞(CSCs)是肿瘤发生的根源, 也是彻底根治肿瘤的靶点. CD133是CSCs标志物之一, 在多种实体肿瘤中表达, 包括结直肠癌、脑胶质瘤等. CD133+细胞比例与肿瘤的侵袭性、病理分级及临床预后密切相关, 可能成为潜在的治疗靶点.

杜祥, 教授, 主任医师, 上海复旦大学附属肿瘤医院

非甾体抗炎药(NSAIDs)阿司匹林除具有解热镇痛抗炎作用外, 还可以降低腺瘤和结直肠癌发生的风险, 有效预防结直肠癌发生, 甚至可以降低患者的死亡率以及改善生存质量. 然而阿司匹林对肿瘤干细胞标志物CD133有何影响以及如何作用于结直肠癌干细胞, 都尚不清楚, 需进一步研究.

英国纽卡斯尔大学的研究发现长期服用小剂量阿司匹林可使易引发结直肠癌的林奇综合征患者肠癌的发病率降低, 他们认为阿司匹林对结肠内的异常干细胞存活有一定影响.

本课题以流式细胞仪直接免疫荧光法检测在不同浓度阿司匹林作用下CDl33的表达变化, 探讨其对结肠癌干细胞的作用.

本文通过对不同浓度阿司匹林对人结肠癌细胞株HT-29和SW480中CSCs标志物CD133表达的影响进行研究, 初步探讨阿司匹林对结直肠癌的影响, 为其临床防治结直肠癌提供了新的相关实验依据.

本文整体思路清晰, 实验设计合理, 方法学恰当, 具有一定的科学性, 实验结果对临床具有一定指导意义.

编辑: 翟欢欢 电编: 鲁亚静

| 1. | Kemper K, Prasetyanti PR, De Lau W, Rodermond H, Clevers H, Medema JP. Monoclonal antibodies against Lgr5 identify human colorectal cancer stem cells. Stem Cells. 2012;30:2378-2386. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 2. | Dalerba P, Cho RW, Clarke MF. Cancer stem cells: models and concepts. Annu Rev Med. 2007;58:267-284. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Kawamoto A, Tanaka K, Saigusa S, Toiyama Y, Morimoto Y, Fujikawa H, Iwata T, Matsushita K, Yokoe T, Yasuda H. Clinical significance of radiation-induced CD133 expression in residual rectal cancer cells after chemoradiotherapy. Exp Ther Med. 2012;3:403-409. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Zhang NH, Li J, Li Y, Zhang XT, Liao WT, Zhang JY, Li R, Luo RC. Co-expression of CXCR4 and CD133 proteins is associated with poor prognosis in stage II-III colon cancer patients. Exp Ther Med. 2012;3:973-982. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Gopisetty G, Xu J, Sampath D, Colman H, Puduvalli VK. Epigenetic regulation of CD133/PROM1 expression in glioma stem cells by Sp1/myc and promoter methylation. Oncogene. 2012; Sep 3. [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 6. | Liu G, Yuan X, Zeng Z, Tunici P, Ng H, Abdulkadir IR, Lu L, Irvin D, Black KL, Yu JS. Analysis of gene expression and chemoresistance of CD133+ cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Mol Cancer. 2006;5:67. [PubMed] |

| 7. | McCowan C, Munro AJ, Donnan PT, Steele RJ. Use of aspirin post-diagnosis in a cohort of patients with colorectal cancer and its association with all-cause and colorectal cancer specific mortality. Eur J Cancer. 2012; Nov 19. [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 8. | Walker AJ, Grainge MJ, Card TR. Aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and colorectal cancer survival: a cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:1602-1607. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 9. | Fernández Calderón M, Betés Ibáñez MT. [Aspirin in the primary prevention of colorectal cancer]. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2012;35:261-267. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Grizzi F, Celesti G, Basso G, Laghi L. Tumor budding as a potential histopathological biomarker in colorectal cancer: Hype or hope? World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6532-6536. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 11. | Karlic H, Herrmann H, Schulenburg A, Grunt TW, Laffer S, Mirkina I, Hubmann R, Shehata M, Marian B, Selzer E. [Tumor stem cell research - basis and challenge for diagnosis and therapy]. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2010;122:423-436. |

| 12. | Mélin C, Perraud A, Akil H, Jauberteau MO, Cardot P, Mathonnet M, Battu S. Cancer stem cell sorting from colorectal cancer cell lines by sedimentation field flow fractionation. Anal Chem. 2012;84:1549-1556. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 13. | Wu XS, Xi HQ, Chen L. Lgr5 is a potential marker of colorectal carcinoma stem cells that correlates with patient survival. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:244. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 14. | Kleist B, Xu L, Kersten C, Seel V, Li G, Poetsch M. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of the adult intestinal stem cell marker Lgr5 in primary and metastatic colorectal cancer. Am J Transl Res. 2012;4:279-290. [PubMed] |

| 15. | de Beça FF, Caetano P, Gerhard R, Alvarenga CA, Gomes M, Paredes J, Schmitt F. Cancer stem cells markers CD44, CD24 and ALDH1 in breast cancer special histological types. J Clin Pathol. 2012; Oct 30. [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Piscuoglio S, Lehmann FS, Zlobec I, Tornillo L, Dietmaier W, Hartmann A, Wünsch PH, Sessa F, Rümmele P, Baumhoer D. Effect of EpCAM, CD44, CD133 and CD166 expression on patient survival in tumours of the ampulla of Vater. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:140-145. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 17. | Wang Y, Zhe H, Ding Z, Gao P, Zhang N, Li G. Cancer stem cell marker Bmi-1 expression is associated with basal-like phenotype and poor survival in breast cancer. World J Surg. 2012;36:1189-1194. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 18. | Sureban SM, May R, Ramalingam S, Subramaniam D, Natarajan G, Anant S, Houchen CW. Selective blockade of DCAMKL-1 results in tumor growth arrest by a Let-7a MicroRNA-dependent mechanism. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:649-659, 659. e1-e2. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 19. | Lin EH, Jiang Y, Deng Y, Lapsiwala R, Lin T, Blau CA. Cancer stem cells, endothelial progenitors, and mesenchymal stem cells: "seed and soil" theory revisited Cancer stem cells, endothelial progenitors, and mesenchymal stem cells: "seed and soil" theory revisited. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2008;2:169-174. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Coco C, Zannoni GF, Caredda E, Sioletic S, Boninsegna A, Migaldi M, Rizzo G, Bonetti LR, Genovese G, Stigliano E. Increased expression of CD133 and reduced dystroglycan expression are strong predictors of poor outcome in colon cancer patients. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2012; 31: 71. [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Horst D, Kriegl L, Engel J, Kirchner T, Jung A. Prognostic significance of the cancer stem cell markers CD133, CD44, and CD166 in colorectal cancer. Cancer Invest. 2009;27:844-850. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 22. | Todaro M, Alea MP, Di Stefano AB, Cammareri P, Vermeulen L, Iovino F, Tripodo C, Russo A, Gulotta G, Medema JP. Colon cancer stem cells dictate tumor growth and resist cell death by production of interleukin-4. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:389-402. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 23. | Francipane MG, Alea MP, Lombardo Y, Todaro M, Medema JP, Stassi G. Crucial role of interleukin-4 in the survival of colon cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4022-4025. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 24. | Ricci-Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E, Biffoni M, Todaro M, Peschle C, De Maria R. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature. 2007;445:111-115. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Elsaba TM, Martinez-Pomares L, Robins AR, Crook S, Seth R, Jackson D, McCart A, Silver AR, Tomlinson IP, Ilyas M. The stem cell marker CD133 associates with enhanced colony formation and cell motility in colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10714. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 26. | Kawamoto H, Yuasa T, Kubota Y, Seita M, Sasamoto H, Shahid JM, Hayashi T, Nakahara H, Hassan R, Iwamuro M. Characteristics of CD133(+) human colon cancer SW620 cells. Cell Transplant. 2010;19:857-864. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 27. | Lee HN, Park SH, Lee EK, Bernardo R, Kim CW. Proteomic profiling of tumor-initiating cells in HT-29 human colorectal cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;427:171-177. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 28. | Jacobs EJ, Newton CC, Gapstur SM, Thun MJ. Daily aspirin use and cancer mortality in a large US cohort. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1208-1217. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 29. | Lou J, Povsic TJ, Allen JD, Adams SD, Myles S, Starr AZ, Ortel TL, Becker RC. The effect of aspirin on endothelial progenitor cell biology: preliminary investigation of novel properties. Thromb Res. 2010;126:e175-e179. [PubMed] |