Published online Nov 21, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i43.7807

Peer-review started: July 20, 2017

First decision: August 10, 2017

Revised: September 28, 2017

Accepted: October 17, 2017

Article in press: October 17, 2017

Published online: November 21, 2017

We report a case of ileo-colonic Histoplasmosis without apparent respiratory involvement in a patient who had previously undergone an orthotopic liver transplant (OLT) for primary biliary cholangitis 15 years earlier. The recipient lived in the United Kingdom, a non-endemic region for Histoplasmosis. However, she had previously lived in rural southern Africa prior to her OLT. The patient presented with iron deficiency anaemia, diarrhoea, abdominal pain and progressive weight loss. She reported no previous foreign travel, however, it later became known that following her OLT she had been on holiday to rural southern Africa. On investigation, a mild granulomatous colitis primarily affecting the right colon was identified, that initially improved with mesalazine. Her symptoms worsened after 18 mo with progressive ulceration of her distal small bowel and right colon. Mycobacterial, Yersinia, cytomegalovirus and human immunodeficiency virus infections were excluded and the patient was treated with prednisolone for a working diagnosis of Crohn’s disease. Despite some early symptom improvement following steroids, there was subsequent deterioration with the patient developing gram-negative sepsis and multi-organ failure, leading to her death. Post-mortem examination revealed that her ileo-colonic inflammation was caused by Histoplasmosis.

Core tip: Histoplasmosis is an endemic fungal infection in many parts of the world; the majority of hosts remain asymptomatic. Clinical manifestations are most commonly pulmonary. We present an unusual case of Histoplasmosis occurring in a patient who was living in a non-endemic region, developed the disease after 15 years of immunosuppression following an orthotopic liver transplant, she presented with no pulmonary symptoms but rather luminal GI and systemic symptoms. This highlights the importance of considering Histoplasmosis within the differential of immunosuppressed patients with a past relevant travel history who present with diarrhea, weight loss, abdominal pain and granulomatous colitis.

- Citation: Agrawal N, Jones DE, Dyson JK, Hoare T, Melmore SA, Needham S, Thompson NP. Fatal gastrointestinal histoplasmosis 15 years after orthotopic liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(43): 7807-7812

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i43/7807.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i43.7807

Granulomatous inflammation of the terminal ileum and right colon is most commonly caused by Crohn’s disease in the United Kingdom, however chronic infections can cause similar appearances. Infectious causes include Mycobacteria tuberculosis and avium intracellulare complex, Yersinia, cytomegalovirus (CMV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Histoplasmosis is not endemic in the United Kingdom however this fungus can remain latent for many years following initial asymptomatic exposure and then may become active with a declining host immune response.

A 74-year-old Caucasian woman underwent orthotopic liver transplantation in 1997 for primary biliary cholangitis. She was referred initially to gastroenterology services in 2012 (15 years post-transplant), with new onset iron deficiency anaemia, loose watery stools with urgency occurring up to 3-4 times/wk, cramping lower abdominal pain and weight loss.

In 2009, she had been investigated for suspected interstitial pneumonitis with a trans-bronchial biopsy. No clear cause was established but she was commenced on steroids with subsequent normal chest imaging. Her other notable past medical history included hypercholesterolaemia, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and paroxysmal atrial tachycardia.

Her medications were mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) 1 g twice daily; tacrolimus (Prograf) 1 mg twice daily, prednisolone 5 mg daily, aspirin, diltiazem, irbesartan, perindopril, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), simvastatin, insulin and modafinil. There was no relevant family history. The patient reported no recent foreign travel however she had lived in Africa for almost 20 years during her 2nd-4th decades, spending periods of time in rural housing. Nonetheless, this was many years prior to liver transplantation and she had no known exposure to tuberculosis (TB). Blood results showed: Hb 11.0 gm/dL, MCV 77.2 fL, WCC 8.2 × 109/L, CRP < 5 mg/L, albumin 44 g/L, ferritin 23 μg/L, bilirubin 3 μmol/L, ALP 129 μ/L and ALT 21 μ/L. Coeliac serology was negative.

Gastroscopy showed gastritis with scattered antral erosions with a negative Helicobacter urease test. The patient’s gastritis and anaemia were managed with lansoprazole and oral iron replacement, respectively, and aspirin was stopped. Routine repeat gastroscopy 6 wk later showed improvement. A colonoscopy was performed that showed an indistinct mucosal vascular pattern in the ascending colon, with biopsies revealing a moderately active, right-sided, chronic granulomatous colitis. Given the lack of any past history of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and the patient’s longstanding immunosuppression, infection was considered. The patient displayed no clinical or laboratory evidence of disseminated infection. She reported no fevers, night sweats, cough or haemoptysis. Inflammatory markers were within normal limits and her chest X-ray (CXR) was normal. Both a Quantiferon gold test and Yersinia serology were negative. A faecal calprotectin was mildly raised at 136 μg/g and small bowel imaging with both magnetic resonance (MR) enterography and a barium follow-through were performed. These showed no significant abnormality, with no evidence of inflammatory bowel disease affecting the small bowel.

As no infective cause had been found, a presumptive diagnosis of mild Crohn’s colitis was made and the patient was started on a trial of mesalazine in November 2012 with almost complete remission of her symptoms when she was seen in clinic 4 mo later. At that time lansoprazole was replaced with ranitidine in case the proton pump inhibitor had contributed to her symptoms. In June 2013 the patient stopped her mesalazine as she felt so well.

Unfortunately her symptoms recurred in December 2013, and at clinic review in May 2014 she had lost 10 kg of weight, was having loose bowel motions 3-4 times/d with associated urgency, nocturnal symptoms and occasional faecal incontinence. She also complained of indigestion and early satiety although no dysphagia.

Gastroscopy in July 2014 showed mild oesophagitis and erythematous gastritis, with biopsy findings of mild focal duodenitis but no granulomatous changes, viral inclusions, parasites, metaplasia or changes suggestive of coeliac disease. Helicobacter urease test was now positive. Repeat colonoscopy showed more significant patchy inflammation and focal ulceration in the right colon. Colonic biopsies showed scattered giant cells and granulomas and terminal ileal biopsies revealed small bowel mucosa distorted with reactive lymphoid tissue and increased eosinophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells in the lamina propria. The pattern was most suggestive of IBD or unusual infections, rather than MMF-related changes, but other drug-related damage could not be excluded. Immunohistochemistry for CMV was negative and acid fast bacilli stain was negative. Mesalazine was restarted, however this time there was no significant symptomatic improvement- prompting a gastroenterology referral.

She was seen by the gastroenterology service in October 2014 at which time her stool frequency was 20 times/d, with ongoing urgency, incontinence and cramping abdominal pain. There was no evidence of blood in the stool or steatorrhoea. She continued to suffer from early satiety, anorexia and had now lost almost 20 kg in weight in the preceding year. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis showed no malignant lesion to explain her symptoms. However it did confirm the appearance of enterocolitis affecting the distal 15 cm of terminal ileum with associated stricturing, as well as the ascending colon up to the hepatic flexure (Figure 1). No abnormality was seen in the lungs. As atypical infections appeared to have been excluded a presumptive diagnosis of Crohn’s disease was made and her steroid dose was increased from a maintenance dose of prednisolone 5 mg that she had been on since 2010, to 30 mg daily (with a tapering course) which resulted in some improvement of symptoms. Her severe diarrhoea continued and culminated in a hospital admission in November 2014 due to severe dehydration and acute kidney injury. Although this improved with intravenous fluids, a second course of increased steroids was not beneficial. Virology screen confirmed negative HIV status. Bloods tests revealed: Hb 112 g/L, MCV 77.2 fL, WCC 10.8 × 109/L, neutrophils 9.09 × 109/L, CRP 15 mg/L, ESR 9 mm/h, albumin 32 g/L, bilirubin 11 μmol/L, ALP 120 μ/L, ALT 11 μ/L and GGT 107 μ/L. A repeat Quantiferon test was again negative.

Given a presumptive diagnosis of progressive Crohn’s disease by December 2014, both surgery and infliximab were considered. However, she rapidly deteriorated with evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding. The patient developed Enterococcus septicaemia likely as a secondary complication of her immunosuppressed state and gut inflammation, with subsequent multi-organ failure, and she sadly died in January 2015.

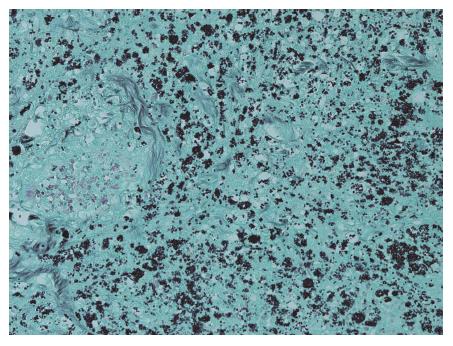

A limited post-mortem examination of the abdomen showed active inflammation and ulceration of the terminal ileum and most of the large intestine. Histological examination revealed abundant intracellular, small oval encapsulated narrow-based budding yeast cells some of which showed a peri-organism halo. The features were those of Histoplasma capsulatum, confirmed with positive Grocott and Giemsa histochemical staining (Figure 2). Her final diagnosis was therefore of gram-negative septicaemia as a complication of gastrointestinal Histoplasmosis, immunosuppression and diabetes. Review of her 2014 ileocolonic biopsies at this time with the addition of Grocott stain highlighted scant forms in keeping with Histoplasmosis.

We discovered on later discussion with her family that although the patient had not lived abroad for any prolonged period following her liver transplant, she had visited Southern Africa during this period and stayed in very basic accommodation. Thus, exposure to Histoplasmosis could have either been at this point, in her already immunosuppressed state, or earlier when she had lived in Africa with a prolonged period of dormancy until transplantation and increasing immunosuppressive treatments.

On reflection, there were opportunities for considering Histoplasmosis within the differential diagnosis. At the time of the second colonoscopy, the pattern of ulcerating ileo-colitis raised the possibility of an unusual infection especially in a long-term immunosuppressed individual with diabetes as well as Crohn’s disease. Mycobacterial, Yersinia, HIV and CMV infections were excluded, though Histoplasmosis was not considered and as such Grocott stain was not performed at this time.

Histoplasmosis is a fungal infection that is typically acquired by inhalation of microscopic spores of the dimorphic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum, an organism found in parts of central and eastern North America, Central and South America, Africa, Asia and Australia[1-5]. Its spores thrive in and thus are predominantly found in nitrogen or phosphate- enriched soils that are associated with large amounts of bat and bird guano, including in caves colonized by bats[6,7] .

Host exposure occurs after inhalation of airborne microconidia (spores) following disturbance of contaminated material in the soil in daily activities, and is extremely common in endemic areas[7,8]. The inhaled H. capsulatum transforms from a mold to a yeast state in the lungs, and is phagocytosed by alveolar macrophages, in which it can multiply. These macrophages then disseminate the organism throughout the rest of the body via the reticuloandothelial system; generally before a cell mediated immune response can develop[7,9] .

The majority (> 99%) of people exposed to H. capsulatum will still be asymptomatic or as the lungs are the entry portals for the organism, show only a mild self-limiting respiratory illness[7]. These people have generally undergone haemategenous dissemination of the organism, however the subsequent development of T cell mediated immunity adequately controls and overcomes the primary infection-preventing it progressing or manifesting[7,8,10,11] .

In the < 1% of patients who do develop clinically appreciable infection, disease severity of Histoplasmosis, is dependent on the number of conidia inhaled and adequacy of the host’s T-cell mediated immune response[7] . As such, the healthy host exposed to a relatively small inoculum of H. capsulatum would remain asymptomatic, while progressive primary disseminated disease would tend to occur in immunosuppressed patients (particularly with cellular immunity compromise), and especially if exposed to large inoculums of the organism.

Risk factors for developing disseminated Histoplasmosis disease at primary infection include: extremes of age, immunosuppressive conditions such as acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), haematological malignancies, solid organ transplants (SOTs), stem cell transplants and congenital T-cell deficiency syndromes, as well as immunosuppressive agents-particularly tumour necrosis factor antagonists[7,12] .

Nonetheless, despite SOT being a risk factor for disseminated histoplasmosis, the absolute incidence of the disease in this patient group still remains low. One prospective surveillance study estimated incidence at 1.6/1000 patients, with the highest incidence being in liver transplant patients, though the most cases overall in kidney transplant recipients, as the latter were so much more common[13]. Subsequent large American studies estimate the overall incidence of Histoplasmosis in patients with SOTs at < 0.5%, despite America having a higher endemic rate of the disease than in Europe[14].

The highest risk of developing Histoplasmosis in an exposed patient was in the first year post transplant, although the risk persists up to 20 years later[14]. Use of mycophenolate for immunosuppression and presence of fungaemia were the 2 specific risk factors for severe histoplasmosis in SOT patients identified by multivariate risk factor analysis[14]. Graft rejection appeared not to be a risk factor for Histoplasmosis in these patients[15].

Moreover it should be noted that even in healthy hosts, though the cell mediated immune response against H. capsulatum may potentially control the primary infection and prevent symptom manifestation, it does not eradicate the organism. As such H.capsulatum can remain silently viable in scattered foci throughout the body for years following initial infection[7]. Leaving these individuals prone to future reactivation of disease with any subsequent decline in cellular immunity; even if this occurs years after they have left the endemic region where they acquired the primary infection[7].

Alternatively, secondary infection can occur if an individual with past exposure to H.capsulatum returns to an endemic region and is exposed to a second large inoculum in a newly immunosuppressed state[7]. As our patient visited endemic regions for H.capsulatum both before and after her liver transplant, it is impossible to elucidate the mechanism by which she developed infection - new primary infection, secondary infection or reactivation.

In terms of clinical presentation of Histoplasmosis in the < 1% of patients who develop disease, there is a huge spectrum, with almost all the organ systems having potential for involvement following dissemination of the organism. There is a broad subdivision into either pulmonary Histoplasmosis (for predominantly respiratory disease) or disseminated Histoplasmosis (for clinical, laboratory or imaging evidence of extra pulmonary disease)[7].

The presentation of pulmonary Histoplasmosis itself is wide-ranging-from rapidly progressive forms which can present like an acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) picture, more chronic cavitatory Histoplasmosis in older patients with underlying past pulmonary disease, and progressive infection of mediastinal lymph nodes causing granulomatous mediastinitis or mediastinal fibrosis[7]. Our patient did present in 2009 with an interstitial fibrosis noted on her CT scans, and was started on steroids for this as no obvious cause was found for it. This seemed to significantly improve both her symptoms and CT scan, her later chest radiology appearances did not suggest any pulmonary disease, so it is presumed this was not a respiratory manifestation of Histoplasmosis.

Disseminated Histoplasmosis manifests even more diversely. It can present with single organ involvement as the sole feature of dissemination, or significant systemic features +/- multi-organ involvement or at the most aggressive end of the spectrum- a systemic inflammatory response syndrome mimicking severe sepsis with complications including hypotension, acute kidney injury and disseminated intravascular coagulation[7].

Systemic symptoms in disseminated histoplasmosis include anorexia, weight loss, fatigue and fevers; examination findings can include lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and in some, mucocutaneous lesions such as ulcerations. Blood tests might reveal raised inflammatory markers including CRP, ESR and ferritin[7].

Gastrointestinal histoplasmosis is believed to be a subset of disseminated disease[16,17] and though organisms are often found within the GI tract (one autopsy series identified the organism in 70% cases of disseminated histoplasmosis[18]), significant symptomatic disease affecting this system is strikingly less common with another study reporting the incidence of clinically diagnosed GI disease in only 3%-12% of patients with disseminated histoplasmosis[19]. This discrepancy between autopsy proven presence of the organism and symptomatic disease is present in various other organ systems too, likely because haematagenous dissemination ensures seeding of the organism throughout the body, though organism presence doesn’t necessarily correlate with clinical disease.

Observed specific GI symptoms aside from the systemic ones already mentioned include intermittent abdominal pain and diarrhea (both watery and bloody), which in severe cases led to malabsorption[7]. The most serious complications were bowel perforation and haemorrhage[9]. The most commonly involved sites were the colon, then the small bowel. Radiological findings include bowel wall thickening, mass like lesions and signs of small bowel obstruction[9], while endoscopically mucosal ulcerations were most commonly seen (both unifocal and multiple), as well as polypoid lesions, obstructive masses and strictures[7,20].

In the case described here, a diagnosis of Histoplamosis was only made at post-mortem examination. However, if the diagnosis had been considered earlier, a urinary Histoplasma antigen test, which is one of the most sensitive diagnostic methods, could have been used[14]. Antigen testing is also suggested as a useful way of monitoring treatment response; antigen concentrations decrease with therapy and increase in disease relapse[8]. Primary detection on ileocolonic biopsy material may also have been possible if a fungal infection had been suspected and Grocott’s methanamine silver stain had been performed at this time.

Histoplasmosis is an eminently treatable disease, with even severe disseminated forms responding well to IV amphotericin B, stepped down to oral azoles for generally at least a 12 mo course[8,14]. If left untreated, this condition often proves fatal.

Overall we have described a case of primarily luminal GI Histoplasmosis, with absent clinical/radiological evidence of pulmonary involvement, occurring 15 years following liver transplantation, in a non-endemic region.

Although Histoplasmosis is a relatively rare disease (even in immunosuppressed patients most prone to developing it); it is eminently treatable if appropriately considered and tested for. Severe disseminated Histoplasmosis if left untreated can often prove fatal. For immunosuppressed patients especially, regardless of where they reside, it is important to consider Histoplasmosis within the differential for ileo-colonic inflammation if a thorough travel history reveals stay in an endemic region, with the possibility of exposure to H. capsulatum, even if this was years prior to immunocompromise. The presence of additional pulmonary and/or systemic features may further suggest this disease, although the absence of these features is not enough to disregard the disease.

The patient presented 15 years post liver transplant for primary biliary cholangitis, with an iron deficiency anaemia, diarrhea, abdominal pain and progressive weight loss while living in the United Kingdom. Travel history revealed she had previously lived in rural Africa prior to transplantation and later that she had on holiday there again post transplantation, living in quite basic accommodation.

The patient had primarily luminal GI symptoms without any pulmonary symptoms of note since she presented in 2012. She went on to develop multi-organ failure ultimately; the diagnosis of Histoplasmosis was made at post-mortem examination.

Includes Crohn’s disease, as well as other atypical infective causes of colitis including human immunodeficiency virus, Yersinia, Tuberculosis and cytomegalovirus (all of which were excluded). Histoplasmosis could have also been considered within the differential diagnosis at this point, given the deterioration in spite of treatment as probable Crohn’s disease, immunosuppression and the travel history to an endemic region for Histoplasmosis. Her initial travel history was reported as not having been abroad for many years.

Although in the case, the diagnosis was only made at post mortem, a urinary Histoplasma antigen test is considered one of the most sensitive diagnostic methods for Histoplasmosis.

Computed Tomography imaging revealed colonic wall thickening, mucosal hyper-enhancement and submucosal oedema reflecting ulceration and inflammation of the ascending colon and hepatic flexure. Endoscopy revealed ileo-colonic ulceration with granulomatous inflammation.

Grocott’s methanamine silver staining and Giemsa histochemical staining identifies Histoplasma capsulatum in biopsy material from affected sites (in this case post mortem GI tract).

Generally should be given to all those presenting with disseminated histoplamosis. Initially treatment consists of intravenous amphotericin B, which can subsequently be stepped down to usually at least a 12-mo treatment course of an oral azole, e.g., itraconazole.

Histoplasmosis is a usually an asymptomatic fungal infection in > 99% of exposed people, with the small percentage who do manifest symptoms having primarily pulmonary symptoms. It is largely immunosuppressed patients (with AIDS or other immune deficiencies) who develop disseminated Histoplasmosis, with primary GI luminal disease being rarely reported in the literature, especially post liver transplantation.

Histoplasmosis is an endemic fungal infection acquired through inhalation of the spores of Histoplasma capsulatum after disruption of soil containing bat and bird guano in endemic regions.

We note the importance of considering Histoplasmosis within the differential diagnosis for immunosuppressed patients presenting with a granulomatous entero-colitis even in non-endemic areas. Taking a full and detailed history of travel to an endemic region at any point in the past is especially important.

The article of Nikita Agrawal and colaborators shows fatal gastrointestinal histoplasmosis 15 years after orthotopic liver transplantation. This is a good piece of work, data are consistent, paper is well written and conclusions based on presented data.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Lu K, Hilmi I, Paramesh ASS, Zhang JJ S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Manos NE, Ferebee SH, Kerschbaum WF. Geographic variation in the prevalence of histoplasmin sensitivity. Dis Chest. 1956;29:649-668. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Colombo AL, Tobón A, Restrepo A, Queiroz-Telles F, Nucci M. Epidemiology of endemic systemic fungal infections in Latin America. Med Mycol. 2011;49:785-798. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Loulergue P, Bastides F, Baudouin V, Chandenier J, Mariani-Kurkdjian P, Dupont B, Viard JP, Dromer F, Lortholary O. Literature review and case histories of Histoplasma capsulatum var. duboisii infections in HIV-infected patients. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1647-1652. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 109] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chakrabarti A, Slavin MA. Endemic fungal infections in the Asia-Pacific region. Med Mycol. 2011;49:337-344. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 51] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | McLeod DS, Mortimer RH, Perry-Keene DA, Allworth A, Woods ML, Perry-Keene J, McBride WJ, Coulter C, Robson JM. Histoplasmosis in Australia: report of 16 cases and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2011;90:61-68. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Teixeira Mde M, Patané JS, Taylor ML, Gómez BL, Theodoro RC, de Hoog S, Engelthaler DM, Zancopé-Oliveira RM, Felipe MS, Barker BM. Worldwide Phylogenetic Distributions and Population Dynamics of the Genus Histoplasma. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004732. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 77] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kauffman CA. Histoplasmosis: a clinical and laboratory update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:115-132. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 711] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 710] [Article Influence: 41.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wheat J, Sarosi G, McKinsey D, Hamill R, Bradsher R, Johnson P, Loyd J, Kauffman C. Practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:688-695. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 292] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Psarros G, Kauffman CA. Colonic histoplasmosis: a difficult diagnostic problem. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2007;3:461-463. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Kauffman CA, Israel KS, Smith JW, White AC, Schwarz J, Brooks GF. Histoplasmosis in immunosuppressed patients. Am J Med. 1978;64:923-932. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Anand A. Diagnosis of systemic histoplasmosis in AIDS patients. South Med J. 1993;86:844-845. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Assi M, McKinsey DS, Driks MR, O’Connor MC, Bonacini M, Graham B, Manian F. Gastrointestinal histoplasmosis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: report of 18 cases and literature review. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;55:195-201. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 62] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Freifeld A, Kauffman C, Pappas P. Endemic fungal infections among solid organ transplant recipients. Presented at Infectious Disease Society of America 43rd Annual Meeting; San Francisco, California; October 6-9, 2005. Abstract 737. . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Assi M, Martin S, Wheat LJ, Hage C, Freifeld A, Avery R, Baddley JW, Vergidis P, Miller R, Andes D. Histoplasmosis after solid organ transplant. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1542-1549. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 113] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kauffman CA, Freifeld AG, Andes DR, Baddley JW, Herwaldt L, Walker RC, Alexander BD, Anaissie EJ, Benedict K, Ito JI. Endemic fungal infections in solid organ and hematopoietic cell transplant recipients enrolled in the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network (TRANSNET). Transpl Infect Dis. 2014;16:213-224. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 118] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kahi CJ, Wheat LJ, Allen SD, Sarosi GA. Gastrointestinal histoplasmosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:220-231. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 96] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cappell MS, Mandell W, Grimes MM, Neu HC. Gastrointestinal histoplasmosis. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:353-360. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Goodwin RA Jr, Shapiro JL, Thurman GH, Thurman SS, Des Prez RM. Disseminated histoplasmosis: clinical and pathologic correlations. Medicine (Baltimore). 1980;59:1-33. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 430] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 338] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wheat LJ, Connolly-Stringfield PA, Baker RL, Curfman MF, Eads ME, Israel KS, Norris SA, Webb DH, Zeckel ML. Disseminated histoplasmosis in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome: clinical findings, diagnosis and treatment, and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1990;69:361-374. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 473] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 395] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lamps LW, Molina CP, West AB, Haggitt RC, Scott MA. The pathologic spectrum of gastrointestinal and hepatic histoplasmosis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:64-72. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 92] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |