Published online Jun 25, 1996. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v2.i2.120

Revised: April 10, 1996

Accepted: May 18, 1996

Published online: June 25, 1996

- Citation: Liao CK, Xie YR, Lu QL. Retrospective analysis of 186 cases of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in recent 5 years. World J Gastroenterol 1996; 2(2): 120-122

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v2/i2/120.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v2.i2.120

We have reviewed 186 cases of patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) who were admitted to our hospital between 1991 and 1995 (the data of 1991 is not complete). The causes of UGIB, in order of frequency, were peptic ulcer (PU), liver cirrhosis (LC), acute lesions of the gastric mucosa (ALGM), tumor, unclear pathogeny, and others. According to the volume and frequency of bleeding, the cases of UGIB, severe gastrointestinal hemorrhage (GIH) and rebleeding were analyzed.

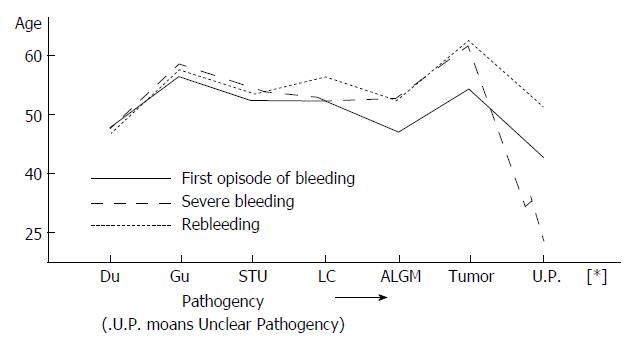

Data were collected for in-patients who had undergone endoscopic examination, and included the time, volume, frequency and location of bleeding. PU cases were divided into subgroups according to duodenal ulcer (DU), gastric ulcer (GU) and special type ulcer (STU). The STU cases included pyloric ulcer and complex ulcer. A total of 186 cases were examined, including 147 men with a mean age of 41.6 years (12.83 years) and 39 women with a mean age of 48.6 years (21-78 years). The mean ages at the first episode of bleeding for DU, GU, STU, LC, tumor, ALGM and unclear pathogeny were 47.8, 58.3, 51.9, 51.6, 53.6, 46.7 and 42 years, respectively. The age distributions for the severe GIH and rebleeding cases are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1.

| First episode of bleeding | Severe GIH | Rebleeding | ||||

| Mean age (range) | Cases | Mean age (range) | Cases | Mean age (range) | Cases | |

| DU | 47.8 (17-30) | 53 | 47.6 (24-62) | 12 | 46.9 (18-57) | 15 |

| GU | 56.3 (43-78) | 16 | 58.3 (52-67) | 3 | 57.0 (45-69) | 6 |

| STU | 51.9 (38-68) | 18 | 54.0 (52-56) | 2 | 53.0 (51-55) | 4 |

| LC | 51.6 (36-64) | 44 | 52.1 (36-60) | 24 | 55.8 (40-57) | 12 |

| ALGM | 46.7 (12-60) | 19 | 52.1 (39-60) | 4 | 52.0 (49-60) | 8 |

| Tumor | 53.6 (41-83) | 26 | 61.2 (45-78) | 3 | 62.2 | 1 |

| Unclear | ||||||

| pathogeny | 420 (23-74) | 10 | 23 | 1 | 50.5 (49-52) | 2 |

| Total | 49.9 | 87 | 49.6 | 49 | 53.9 | 48 |

| Pathogeny | Winter | Spring | Summer | Autumn | Total (%) | ||||||||

| 12 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | ||

| PU | 11 | 11 | 7 | 15 | 7 | 10 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 87 (46.7) |

| LC | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 44 (23.7) |

| ALGM | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 19 (10.2) |

| Tumor | 2 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 26 (14.0) |

| Unclear pathogeny | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 10 (5.4) |

| Total | 21 | 23 | 15 | 31 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 13 | 12 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 186 (100) |

| Severe GIH | 7 | 4 | 8 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 49 (26.3) |

| Rebleeding | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 48 (25.8) |

There was no obvious difference among the morbidities from 1991 to 1995. The annual numbers of hospitalized patients from 1991 to 1995 were 36, 40, 33, 44 and 33, respectively. The morbidity was higher in January, March, May and December. However, cases of bleeding in PU was most common from December to March and less common from August to October. The seasonal fluctuation affected the bleeding more in DU and STU than in GU. The incidence of severe GIH was slightly higher from December to March and that of rebleeding was higher from January to March.

Of the 186 patients, there were 87 cases of PU (46.7%), including DU (28.5%), GU (8.6%), and STU (9.6%); 44 cases of LC (23.7%), including bursting of esophageal, gastric varices; 26 cases of tumor (14%), including esophageal cancer (7), gastric cancer (17), gastric adenoma (1), and biliary tract cancer (1); 19 cases of ALGM (10.2%); and 10 cases of unclear pathogeny (5.4%). The sites of UGIB are: esophagus in 36 cases (19.4%), stomach in 75 cases (40.3%), duodenum in 62 cases (33.3%), pylorus in 12 cases (6.5%), and biliary tract in 1 case (0.5%).

There were 139 cases of UGIB in our series and 48 cases of rebleeding (25.8%), consisting of 42 men and 6 women (M/F ratio of 7:1). Among these patients, 25 suffered from PU (52.1%), including 15 cases of DU, 6 of GU, and 4 of STU; 12 suffered from LC, 8 from ALGM, 2 from unclear pathogeny, and 1 from tumor. The highest rebleeding frequency of LC was 8 times, and that of DU was 5 times. On the other hand, according to the volume of bleeding, 49 cases (26.3%) were severe GIH (bleeding volume > 800 mL per day (24 h)[1]), 57 cases (31%) were moderate GIH, and 80 cases (43.7%) were of slight bleeding (with melena and Hb of > 60 g/L and 90 g/L, respectively). Forty-one males and 8 females had severe GIH (M/F ratio of 5.1:1). According to the pathogeny of severe GIH, the numbers of LC, PU (including DU), ALGM, tumor, and unclear pathogeny were 24 (48.9%), 17 (34.2%), 4 (8.2%), 3 (6.1%) and 1 (2%), respectively (Table 1). Rebleeding occurred in 18 cases of severe GIH (36.2%), including 10 of LC, 7 of PU and 1 of ALGM.

A total of 38 patients were treated surgically, among which 14 (16.1%) had PU, 7 (15.9%) had bursting of esophageal and gastric varices, and lesion of esophageal and gastric mucosa, and 17 (65.4%) had tumor. The PU cases included 9 DU, 1 of which perforated and hemorrhaged, 5 GU, and 8 patients who suffered from rebleeding after surgery at the anastomotic stoma. Five of the 7 LC patients had rebleeding after surgery. There were 13 deaths, including 8 patients with severe GIH of LC, 3 with tumor and bleeding, and 2 with severe GIH from DIC with gastric mucosa hemorrhage. The surgical and mortality rates of non-tumor UGIB were 15.1% and 7.2%, respectively. The principal treatment for UGIB was antacid agents, with 120 of 186 patients having taken H2-receptor blockers and 65 having taken Losec. All of these patients showed improvement to varying degrees. The recovery rate of UGIB was 93.1%, and the improvement rate was 6.9% (all of the 6 patients were discharged from the hospital for different causes). The recovery rate of LC-GIH was 95%. The other UGIB patients, excepting those with tumors, recovered.

Mino et al[2] reported that the major causes of UGIB are PU (54.13%), bursting of esophageal and gastric varices (10.73%), and ALGM (6.72%); the etiology of hemorrhage could not be established in 8% of cases. Our data are in agreement with these. Another study showed that bleeding of PU has a tendency to increase year by year, the age of the hospitalized patients suffering from PU bleeding was between 40-60 years, with the morbidity increasing gradually after 60 years old[3]. This is also consistent with our results. PU bleeding and rebleeding are characterized by some seasonal distributions, with the highest incidence of bleeding being observed during winter and early spring, accounting for 50.6% of all PU bleeding cases and 52.1% of rebleeding cases. These results are similar to those reported by some scholars[3,4]. The reasons why the cold climate is associated with more frequent DU bleeding may be related to an enhanced aggressive factor and a weakened defending factor during that period. Another reason is that patients take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (commonly known as NSAIDs) more often in these seasons.

The causes of LC hemorrhage include bursting of esophageal and gastric varices, ulcer, lesions of gastric mucosa, and so on. Because this condition is more severe and dangerous, we should pay more attention to it. Staritz[5] has reported that the mortality rate of patients with LC from esophageal variceal bleeding can reach up to 30% after the first bleeding episode. Meanwhile, there is an obvious relationship between liver function and severe GIH. The liver function of the 8 patients who died in our case series suffered from severe GIH of LC and showed Child grade C. The criteria gives a better evaluation of risk of hemorrhage. However, this kind of UGIB and rebleeding occurs more often in cold climate, suggesting that the related factors that produce harmful effects on the blood vessels may increase due to the cold climate.

According to the number of cases, the features of bleeding of tumor, ALGM and unclear pathogeny ranked the third, fourth, and fifth, respectively. Since the cause of tumor bleeding is always indistinct, the prognosis is better after the pathogeny and site are determined since an appropriate therapy may be identified and applied. Of the 26 patients, only 17 were indicated for surgery. For ALGM, the site is diffuse and presents acute changes visible by endoscopy. Four of the 19 patients with severe hemorrhage were aged > 55 years. The function of the mucosal barrier is easily damaged, inducing severe hemorrhage. Because the examination was not made in time and the technique itself was limited, the underlying causes of 10 cases of hemorrhage were unknown. These patients were the youngest, as represented by the mean age (only 1 who had rebleeding was aged 74 years), and without complications of other organs; thus, their gastric mucosa regenerated rapidly and they recovered well after bleeding. It is possible that these patients may have had a lesion of gastric mucosa, but there are likely other pathogenies, such as Dieulafoy lesion.

Age is another important factor for UGIB, severe GIH and rebleeding. Our data show that ages at the first episode of bleeding for GU and tumor are the oldest in our study population (56.3 and 53.5 years respectively); the next coincided with STU, LC and DU (51.9, 51.6 and 47.8 years respectively), and the youngest were for ALGM and unclear pathogeny (46.7 and 42 years respectively) (Figure 1). The distribution curve of age and etiology of bleeding gives the explanation for the epidemiological tendency of UGIB showing different pathogeny according to age, which is consistent with Nishida′s view[6].

Our data also demonstrated that age distribution curves for both severe GIH and rebleeding are higher (26.3% and 25.8%) than that for the first episode of bleeding (Figure 1). The rebleeding rate was also high (36.2%) after severe GIH. These findings may be related to the poor contractility of bleeding vessels and the general poor response to drug treatment in older patients with arteriosclerosis. It has also been demonstrated that severe hemorrhage is more common in patients older than 60 years, and reportedly associated with a death rate of 23.2%[7]. The etiology of severe hemorrhage varies in different areas of our country. In the northeast, the order of frequency reported is LC, PU and ALGM[1], similar to our results. It has also been reported that in this kind of hemorrhage, 20.15% and 29.25% of cases are persistent and self-limiting[2]. However, we think this notion is contradictory to the bursting of esophageal and gastric varices. Cases of severe GIH caused by ALGM have increased in recent years, from 3.6% in the 1970s to 10% in the most current report, and this condition has emerged as a common pathogeny of UGIB[1]; so, greater importance should be attached to it for future research studies.

Original title:

S- Editor: Filipodia L- Editor: Jennifer E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Mon XM, Zhang DH. The severe upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Clinics General Surg. 1992;7:373-736. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Miño Fugarolas G, Jaramillo Esteban JL, Gálvez Calderón C, Carmona Ibáñez C, Reyes López A, De la Mata García M. [An analysis of a general prospective series of 3270 upper digestive hemorrhages]. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1992;82:7-15. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Zheng ZT, Wang YB, Song QS. Analysis of hospitalization of peptic ucler patients. Chin J Practical Intern Med. 1995;15:15-17. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Stermer E, Levy N, Tamir A. Seasonal fluctuations in acute gastrointestinal bleeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20:277-279. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Staritz M. [Epidemiology and predictability of variceal hemorrhage]. Langenbecks Arch Chir Suppl II Verh Dtsch Ges Chir. 1990;355-359. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Nishida K, Nojiri I, Kato M, Higashijima M, Takagi K, Akashi R. [Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the elderly]. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 1992;29:829-835. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Yavorski RT, Wong RK, Maydonovitch C, Battin LS, Furnia A, Amundson DE. Analysis of 3294 cases of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in military medical facilities. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:568-573. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |