Published online Aug 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i32.5357

Revised: June 15, 2013

Accepted: July 18, 2013

Published online: August 28, 2013

AIM: To study the evolution of gastrointestinal symptoms and associated factors in Chinese patients with functional dyspepsia (FD).

METHODS: From June 2008 to November 2009, a total of 1049 patients with FD (65.3% female, mean age 42.80 ± 11.64 years) who visited the departments of gastroenterology in Wuhan, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Xi’an, China were referred for this study. All of the patients fulfilled the Rome III criteria for FD. Baseline demographic data, dyspepsia symptoms, anxiety, depression, sleep disorder, and drug treatment were assessed using self-report questionnaires. Patients completed questionnaires at baseline and after 1, 3, 6 and 12 mo follow-up. Comparison of dyspepsia symptoms between baseline and after follow-up was explored using multivariate analysis of variance of repeated measuring. Multiple linear regression was done to examine factors associated with outcome, both longitudinally and horizontally.

RESULTS: Nine hundred and forty-three patients (89.9% of the original population) completed all four follow-ups. The average duration of follow-up was 12.24 ± 0.59 mo. During 1-year follow-up, the mean dyspeptic symptom score (DSS) in FD patients showed a significant gradually reduced trend (P < 0.001), and similar differences were found for all individual symptoms (P < 0.001). Multiple linear regression analysis showed that sex (P < 0.001), anxiety (P = 0.018), sleep disorder at 1-year follow-up (P = 0.019), weight loss (P < 0.001), consulting a physician (P < 0.001), and prokinetic use during 1-year follow-up (P = 0.035) were horizontally associated with DSS at 1-year follow-up. No relationship was found longitudinally between DSS at 1-year follow-up and patient characteristics at baseline.

CONCLUSION: Female sex, anxiety, and sleep disorder, weight loss, consulting a physician and prokinetic use during 1-year follow-up were associated with outcome of FD.

Core tip: This is a prospective study with Chinese patients to explore the clinical course of functional dyspepsia (FD), and evaluate the potential risk factors associated with it, using the Rome III criteria both longitudinally and horizontally. The sample size in this study was large and there was a good response rate. The mean dyspepsia symptom score for both total and individual symptoms showed a significant gradually reduced trend. Female sex, anxiety, and sleep disorder, weight loss, consulting a physician and prokinetic use during 1-year follow-up were associated with the outcome of FD.

- Citation: Yu J, Liu S, Fang XC, Zhang J, Gao J, Xiao YL, Zhu LM, Chen FR, Li ZS, Hu PJ, Ke MY, Hou XH. Gastrointestinal symptoms and associated factors in Chinese patients with functional dyspepsia. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(32): 5357-5364

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i32/5357.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i32.5357

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a highly prevalent gastrointestinal disorder that is defined by the presence of symptoms thought to originate in the gastroduodenal region, without identifiable cause and diagnosed by routine tests[1,2]. According to the Rome III criteria, patients are classified as postprandial distress syndrome (PDS) or epigastric pain syndrome (EPS) based upon the predominant symptom (i.e., postprandial fullness, early satiation, or epigastric pain, and burning)[1]. The reported prevalence of FD symptoms varies between 19% and 41%[3]. FD has a significant impact on quality of life and imposes a substantial economic burden on society due to costs of physician visits, medication, and absenteeism[3,4].

The course of FD is always chronic, with a relapsing-remitting pattern, and has been poorly studied[5]. In spite of the prevalence of FD being stable over time, the reverse in symptom status is high[6]. Many studies have reported that a significant number of patients with FD improve or become asymptomatic over time, suggesting that a proportion of patients go into symptom remission, but the rates of symptom disappearance varies widely[5,7].

The pathophysiology of FD also remains poorly understood and is likely to be multifactorial[8]. Many pathogenic factors have been proposed for FD including genetic, environmental, pathological, and psychological factors[9]. Psychosocial factors such as depression, anxiety and stressful life events (e.g., history of abuse) are considered to play a role in the development of FD[10,11]. A relationship between Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and FD has also been reported[12]. Similarly, several studies have demonstrated that sleep disorder is associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and FD[13-15]. Nevertheless, it is not clear whether such pathogenic factors affect the clinical course of FD.

Accordingly, this longitudinal study followed up a group of Chinese patients with FD over 1 year. We aimed to explore the evolution of FD symptoms, and evaluate the potential risk factors both longitudinally and horizontally.

A total of 1049 patients with FD (364 male and 685 female, aged 20-79 years, mean 42.80 ± 11.64 years) who fulfilled the Rome III criteria were enrolled. These were outpatients who visited departments of gastroenterology in five cities in China (Wuhan, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Xi’an) from June 2008 to November 2009.

The patients had one or more dyspeptic symptoms, including troublesome postprandial fullness, early satiation, epigastric pain, or epigastric burning for the past 3 mo, with symptom onset at least 6 mo before diagnosis. All of the FD patients had undergone upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, abdominal ultrasound, and/or barium meal X-ray examination in a tertiary hospital. In all cases, there was no evidence of organic, systemic, or metabolic disease that was likely to explain the symptoms.

Patients were excluded if they: (1) had upper gastrointestinal organic diseases such as esophagitis, peptic ulcer, or peptic neoplasm that were found by gastroscopy or barium meal X-ray examination and abdomen ultrasonography; (2) had chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, hyperthyroidism, scleroderma, chronic renal failure, or congestive heart failure; (3) had a history of abdominal surgery; or (4) were pregnant or preparing to conceive a child, or lactating during the study period.

Baseline data: All 1049 FD patients were asked to finish a self-report questionnaire face to face. To ensure content validity and usability, physicians were trained initially to give instructions to patients and did not intervene with the patients’ medical management.

The baseline self-reported questionnaire included several clinical variables involving demographics (age, sex, height, weight, and marital status), tobacco and alcohol use, educational level, economic situation, life satisfaction, physical labor, H. pylori status, severity and frequency of each dyspepsia symptom, bowel symptom comorbidity, psychosocial factors (anxiety and depression), sleep disorder, major mental stimulation, history of abuse and drug treatment (prokinetics, gastric mucosa protectants, antacids, anti-H. pylori therapy, and traditional Chinese medicine). The data for dyspepsia and bowel symptoms were collected using a Chinese version of the validated Rome III diagnostic questionnaire for adult functional gastrointestinal disease[16]. This questionnaire has been repeatedly tested and carefully validated[17].

Follow-up data: FD patients were asked to visit the department of gastroenterology to finish a follow-up questionnaire at 1, 3, 6 and 12 mo after the first visit. The follow-up questionnaire was the same as the baseline questionnaire, but did not include some details such as sex, educational level, economic situation, life satisfaction, physical labor, major mental stimulation, and history of abuse.

At upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, biopsies were acquired and processed for rapid urease test. A 13C/14C-urea breath test was also used to assess H. pylori status.

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated and categorized as weight (kg)/height (m2) according to World Health Organization recommendations.

Economic situation was classified as rich, sufficient, well-off and poor according to the expending percentage for food in whole income as < 1/5, < 1/3, 1/2, and > 1/2.

Educational level was divided into seven: illiteracy, elementary school, junior high school, high school, junior college, university, and graduate and above. If the patients were illiterate or had finished elementary school education, they were judged as having a low level of education. If the patients had completed junior high school or high school education, they were regarded as having a medium level of education. Patients who had completed junior college education or above were considered to have a high level of education.

Current smokers were defined as individuals smoking cigarettes and having no other former tobacco use. Alcohol use was defined as consumption of > 100 g/wk alcohol.

Dyspeptic symptoms that were recorded and assessed included postprandial fullness, early satiation, epigastric pain, epigastric burning, belching, nausea, vomiting, and bloating. Each symptom was graded and scored on a Likert scale according to its severity as follows: 0, absent; 1, mild (not influencing daily activities); 2, relevant (diverting from but not urging modifications in daily activities); and 3, severe (influencing daily activities markedly enough to urge modifications). Frequency of each symptom was also graded as follows: 1, occurring < 1 d/mo; 2, occurring 1 d/mo; 3, occurring 2-3 d/mo; 4, occurring 1 d/wk; 5, occurring > 1 d/wk; and 6, occurring every day. The score for a single dyspeptic symptom was an aggregate of frequency and severity ratings, ranging from 0 to 9. Dyspeptic symptoms score (DSS) was assessed by summing the score of eight dyspepsia symptoms.

The questionnaires used for assessment of psychological factors and sleep disorder were established according to a Chinese version of the Validated Rome III Psychosocial Alarm Questionnaire for functional gastrointestinal disease[16,18]. In previous studies these questionnaires have been used to assess the psychological factors and sleep status of Chinese patients[19].

For problems related to anxiety and depression in the past 3 mo, the patients answered the question: Did you feel nervous irritable or depressed (yes/no)? If patients chose yes, they had to answer the next question about how often they felt nervous irritable or depressed: 1, occasionally; 2, sometimes; 3, frequently; 4, most of the time. Patients felt nervous irritable or depressed frequently or most of the time, indicating that anxiety or depression was present[16]. In the present study, we judged “nervous irritability” or “depression” occurring frequently or most of the time as “anxiety state” or “depression state”.

Subjective sleep disorder in patients was measured with one question (yes/no). Symptoms of sleep disorder included trouble falling asleep, shallow sleep/dreaminess, sleep time < 6 h, early morning awakening, and daytime sleepiness.

A history of abuse in patients was measured with a question as follows: Have you ever been abused (yes/no)? If patients chose yes, they stated whether the abuse was physical or mental.

All statistical analyses were assessed using SPSS for Windows version 13. A two-sided P value < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Data are presented as mean ± SD. To assess whether those who completed all four follow-ups were representative of the original study population, we compared the baseline characteristics between the follow-up population and those who were lost to follow-up, using Pearson’s χ2 test (categorical variables), Mann-Whitney U test (ordinal variables, such as BMI) and t test (continuous variables). Comparison between all individual dyspepsia symptoms at initial visit and at the four follow-ups was explored using multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) of repeated measuring. Univariate association measures between patient characteristics (baseline as well as 1-year follow-up) and DSS at 1-year follow-up were calculated using Pearson’s correlation and non-parametric one-way ANOVA. Risk factors associated with DSS at final follow-up, both longitudinally and horizontally, were determined by performing multiple linear regressions.

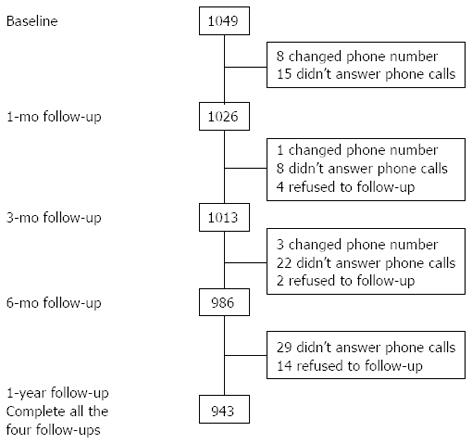

Of the 1049 FD patients originally enrolled, 1026 patients (97.8% of the baseline sample) completed the 1-mo study; 1013 patients (96.6% of the baseline sample) completed the 3-mo study; 986 patients (94.0% of the baseline sample) completed the 6-mo study; and 943 patients (89.9% of the baseline sample) completed the 1-year study (Figure 1).

The 943 patients who completed the baseline and all four follow-up questionnaires were included in this study. The average duration of follow-up was 12.24 ± 0.59 mo. The mean age of the follow-up population was 42.99 ± 11.74 years, and 603 (63.9%) were female; 176 (18.7%) had bowel symptom comorbidity, and 230 (24.4%) were positive for H. pylori. Men, alcohol users, those with higher educational level and better economic situation, and those who had consulted a physician were significantly more likely to be successfully followed up (P < 0.05 for all analyses) (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Complete all four follow-ups (n = 943) | Lost to follow-up (n =106) | P value |

| Sex (female) | 603 (63.9) | 82 (77.4) | 0.006 |

| Smoker | 202 (21.4) | 16 (15.1) | 0.128 |

| Alcohol user | 278 (29.5) | 15 (14.2) | 0.001 |

| Marital status (married) | 815 (86.4) | 95 (89.6) | 0.357 |

| Physical labor | 0.537 | ||

| High | 34 (3.6) | 3 (2.8) | |

| Medium | 238 (25.2) | 31 (29.2) | |

| Low | 671 (71.2) | 72 (67.9) | |

| Life satisfaction | |||

| High | 171 (18.1) | 13 (12.3) | 0.292 |

| Medium | 732 (77.6) | 90 (84.9) | |

| Low | 40 (4.2) | 3 (2.8) | |

| Educational level | 0.011 | ||

| High | 336 (35.6) | 28 (26.4) | |

| Medium | 455 (48.3) | 51 (48.1) | |

| Low | 152 (16.1) | 27 (25.5) | |

| Economic situation | 0.03 | ||

| Rich | 40 (4.2) | 3 (2.8) | |

| Sufficient | 405 (42.9) | 34 (32.1) | |

| Well-off | 469 (49.7) | 67 (63.2) | |

| Poor | 29 (3.1) | 2 (1.9) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.071 | ||

| Obesity | 138 (14.6) | 10 (9.4) | |

| Normal | 709 (75.2) | 81 (76.4) | |

| Thin | 96 (10.2) | 15 (14.2) | |

| Bowel symptom | 176 (18.7) | 23 (21.7) | 0.45 |

| H. pylori status (positive) | 230 (24.4) | 22 (20.8) | 0.14 |

| Consulting a physician | 908 (96.3) | 91 (85.8) | < 0.001 |

| Mean age (yr) | 42.99 ± 11.74 | 41.11 ± 10.65 | 0.116 |

| DSS | 22.05 ± 9.89 | 20.25 ± 10.77 | 0.079 |

The mean DSS in FD patients at baseline, and 1, 3 and 6 mo and 1 year follow-up was 22.05 ± 9.89, 14.04 ± 9.38, 12.05 ± 9.09, 10.08 ± 8.89 and 8.97 ± 8.62, respectively. This means that during 1 year follow-up, the mean DSS in FD patients showed a significant gradually reduced trend and all pairwise comparisons were statistically significant (all P < 0.001).

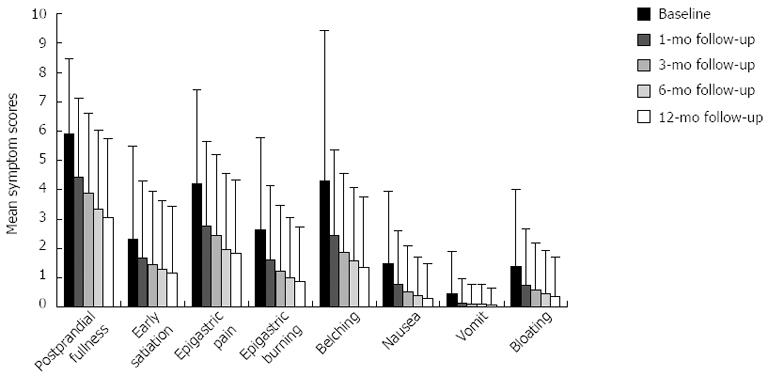

Similar differences were observed for all individual symptoms (Figure 2). The mean symptom scores for both postprandial fullness and belching during 1 year follow-up showed a significant reduced trend and all pairwise comparisons were statistically significant (all P < 0.001).

The mean symptom scores for early satiation, nausea and bloating during 1 year follow-up decreased significantly and all pairwise comparisons were statistically different (all P < 0.001, except for the difference between 3 and 6 mo follow-up, P = 0.037, P = 0.035, P = 0.102, and the difference between 6 mo and 1 year follow-up, P = 0.333, P = 0.034, P = 0.213).

There was a marked decreased trend in mean symptom scores for both epigastric pain and epigastric burning during 1-year follow-up, and there were significant differences in all pairwise comparisons (all P < 0.001, except for the difference between 6 mo and 1 year follow-up, P = 0.401, P = 0.028).

The mean symptom scores for vomiting was reduced markedly, with all pairwise comparisons showing a significant difference (all P < 0.001, except for the difference between 1 mo and 3 mo follow-up, P = 0.330; the difference between 3 mo and 6 mo follow-up, P = 0.959; the difference between 6 mo and 1 year follow-up, P = 1.0).

Longitudinal associations: For patient characteristics at baseline, univariate correlates analysis revealed that history of abuse was associated with DSS at 1-year follow-up (P = 0.025), while no association was found for other variables such as sex, age, BMI, anxiety, depression, sleep disorder, H. pylori status, DSS at baseline, and drug treatment before baseline (Table 2). Multiple linear regression analysis showed no relationship between DSS at 1-year follow-up and patient characteristics at baseline (Table 2).

| Variable (at baseline) | Longitudinal associations | |||||||

| Univariate correlates | Multiple linear regression | |||||||

| r1 | F2 | P | B | β | t | P | R2Model | |

| Sex3 | 3.489 | 0.062 | 0.161 | 0.009 | 0.208 | 0.835 | 0.019 | |

| Age | 0.002 | 0.959 | -0.007 | -0.009 | -0.224 | 0.823 | ||

| BMI | 0.007 | 0.835 | -0.024 | -0.009 | -0.248 | 0.804 | ||

| Smoking | 1.894 | 0.169 | 1.228 | 0.058 | 1.368 | 0.172 | ||

| Alcohol consumption | 0.02 | 0.887 | -0.665 | -0.035 | -0.876 | 0.381 | ||

| Major mental stimulation | 1.288 | 0.257 | -0.421 | -0.013 | -0.365 | 0.715 | ||

| History of abuse | 5.022 | 0.0254 | -3.774 | -0.062 | -1.762 | 0.078 | ||

| Anxiety | 0.106 | 0.745 | 0.897 | 0.030 | 0.777 | 0.437 | ||

| Depression | 0.937 | 0.333 | -1.549 | -0.044 | -1.157 | 0.248 | ||

| Sleep disorder | 1.831 | 0.176 | -0.683 | -0.040 | -1.131 | 0.259 | ||

| Bowel symptom | 0.17 | 0.680 | 0.442 | 0.020 | 0.580 | 0.562 | ||

| H. pylori status | 0.461 | 0.631 | -0.269 | -0.027 | -0.782 | 0.434 | ||

| DSS | -0.014 | 0.667 | -0.015 | -0.018 | -0.502 | 0.616 | ||

| Treatments in the previous months before baseline | ||||||||

| Consulting a physician | 0.753 | 0.386 | 0.468 | 0.027 | 0.804 | 0.421 | ||

| Prokinetic use | 0.077 | 0.782 | -0.598 | -0.034 | -0.933 | 0.351 | ||

| Gastric mucosa protectant use | 1.407 | 0.236 | 0.611 | 0.034 | 0.971 | 0.332 | ||

| Antacid use | 1.381 | 0.24 | 0.589 | 0.034 | 0.906 | 0.365 | ||

| Anti-H. pylori therapy | 1.014 | 0.314 | 0.431 | 0.018 | 0.539 | 0.590 | ||

| Traditional Chinese medicine use | 0.005 | 0.945 | -0.025 | -0.001 | -0.042 | 0.966 | ||

Horizontal associations: For patient characteristics at 1-year follow-up, univariate correlates analysis found that age (P < 0.001), alcohol consumption (P = 0.024), anxiety (P < 0.001), depression (P < 0.001), sleep disorder (P < 0.001), bowel symptoms (P < 0.001), weight loss (P < 0.001), consulting a physician (P < 0.001), prokinetic use (P < 0.001), gastric mucosa protectant use (P < 0.001), antacid use (P < 0.001), and traditional Chinese medicine use (P < 0.001) were significantly associated with DSS (Table 3).

| Variable (at 1-yr follow-up) | Horizontal associations | |||||||

| Univariate correlates | Multiple linear regression | |||||||

| r1 | F2 | P | B | β | t | P | R2Model | |

| Sex3 | 3.489 | 0.062 | 0.585 | 0.033 | 6.356 | < 0.0014 | 0.98 | |

| Age | 0.139 | < 0.0014 | -0.002 | -0.002 | -0.456 | 0.649 | ||

| Time of follow-up (mo) | -0.035 | 0.288 | -0.121 | -0.008 | -1.837 | 0.067 | ||

| Smoking | 1.109 | 0.293 | -0.242 | -0.009 | -1.533 | 0.126 | ||

| Alcohol consumption | 5.132 | 0.0244 | 0.204 | 0.008 | 1.346 | 0.179 | ||

| Anxiety | 13.257 | < 0.0014 | 0.292 | 0.015 | 2.373 | 0.0184 | ||

| Depression | 27.452 | < 0.0014 | -0.052 | -0.002 | -0.392 | 0.695 | ||

| Sleep disorder | 69.219 | < 0.0014 | 0.216 | 0.012 | 2.346 | 0.0194 | ||

| Bowel symptom | 51.053 | < 0.0014 | 0.185 | 0.007 | 1.377 | 0.169 | ||

| H. pylori status | 1.563 | 0.210 | -0.035 | -0.003 | -0.759 | 0.448 | ||

| Treatments during 1-yr follow-up period | ||||||||

| Consulting a physician | 224.718 | < 0.0014 | 0.893 | 0.051 | 9.168 | < 0.0014 | ||

| Prokinetic use | 59.340 | < 0.0014 | 0.200 | 0.012 | 2.113 | 0.0354 | ||

| Gastric mucosa protectant use | 22.857 | < 0.0014 | -0.014 | -0.001 | -0.147 | 0.883 | ||

| Antacid use | 19.313 | < 0.0014 | -0.023 | -0.001 | -0.266 | 0.790 | ||

| Anti-H. pylori therapy | 1.825 | 0.177 | -0.075 | -0.003 | -0.635 | 0.526 | ||

| Traditional Chinese medicine use | 50.799 | < 0.0014 | -0.062 | -0.004 | -0.755 | 0.450 | ||

| Weight loss during 1-yr follow-up period | 0.988 | < 0.0014 | 1.040 | 0.961 | 186.775 | < 0.0014 | ||

Multiple linear regression analysis showed that sex (P < 0.001), anxiety (P = 0.018), sleep disorder (P = 0.019), weight loss (P < 0.001), consulting a physician (P < 0.001) and prokinetic use (P = 0.035) were significantly associated with DSS, while age, depression, alcohol consumption, bowel symptoms, and use of gastric mucosa protectants, antacids and traditional Chinese medicine were not associated with it (Table 3).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first published prospective study with Chinese patients to explore the clinical course of FD, and evaluate potential risk factors associated with FD, using the Rome III criteria, both longitudinally and horizontally. We selected a large group of FD patients from five cities in China. After their initial visit, patients were followed up at 1, 3 and 6 mo and 1 year.

The sample size was large and we had a good response rate to all parts of the study. We compared the baseline characteristics between the follow-up population and those who were lost to follow-up. We found that men, alcohol users, those with higher educational level and better economic situation, and those who had consulted a physician were significantly more likely to be successfully followed up. This is consistent with previous reports[20,21]. There were some demographic differences between responders and non-responders, but the magnitude of these differences was small and the individuals included in our follow-up study were broadly representative of the original enrolled FD patients, suggesting that the results of our study are persuasive.

The novel finding of our study was that the total DSS in FD patients showed a significant gradually reduced trend during 1 year follow-up, and similar differences were found for all individual symptoms. It seems that patients feel much better at the final follow-up and complain of less discomfort. Several previous studies reported improved symptoms during a period of follow-up, which is in line with our findings[5]. Kindt et al[22], in a 5-year follow-up study, found that about half of FD patients reported disappeared or improved symptoms. Pajala et al[23] observed a marked reduction in DSS in FD patients in Finland after 1 year follow-up. Heikkinen et al[24], in a long-term perspective study, also concluded that the stability of the symptom-based subgroups over time was poor. However, all of these studies only compared two time points, while our study compared five points.

Furthermore, we identified risk factors that influenced the clinical course of FD. Over the past decade, the correlation between psychological factors and functional gastrointestinal disorders has been confirmed in several clinical case-control studies[25,26]. Koloski et al[27] found that anxiety was an evident independent predictor for FD. Aro et al[28], in a Swedish population-based study, showed that anxiety but not depression was linked to FD and PDS but not to EPS. In the present study, anxiety at 1-year follow-up was also found to be horizontally associated with DSS, which is in keeping with previous studies.

Sleep disorder is a common phenomenon in all FD patients. Dyspeptic symptoms can interfere with sleep, and disrupted sleep may also potentially exacerbate FD symptoms due to the hyperalgesic effect of sleep loss. Cremonini et al[14], in a study involving 3228 respondents, found that sleep disturbances were linked to both upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms in the general population. Lacy et al[15] revealed that there was a relationship between FD and sleep disorder, and sleep disorder in FD patients appeared to be associated with symptom severity and higher levels of anxiety. We also discovered an association between sleep disorder at 1-year follow-up and FD outcome.

Recent cross-sectional population studies discovered that weight loss correlated most strongly with early satiety, followed by nausea and vomiting[29]. A longitudinal study in Belgium found that weight loss was independently associated with FD-specific quality of life at follow-up, and there was a trend association between weight loss and DSS at follow-up[22]. In this study, we did not have information about weight difference between dyspepsia symptom onset and initial visit. However, we collected data on patients’ weight at baseline and at final follow-up, and observed that weight loss during 1 year follow-up was independently associated with DSS.

We showed an association between sex and FD outcome, indicating that women may have higher DSS at 1-year follow-up than men have, which is consistent with a cross-sectional study in Taiwan[30]. There was no association between H. pylori status and DSS at 1-year follow-up, which is similar to another prospective 2-year follow-up study from Taiwan[31].

An important finding in our study was that many individuals reported persistent symptoms despite consultation and prokinetic use during 1 year follow-up. Similarly, two recent studies have also reported persistence of symptoms in drug-treated patients[32,33]. It is probable that patients consulting a physician have the most severe symptoms, and they often take prescribed drugs on an on-demand basis. In addition, most individuals (n = 511, 54% of follow-up patients) in our study had a prescription of prokinetic during 1 year follow-up. These may be the reasons why patients consulting a physician and taking prokinetic still have continuous symptoms or even more severe symptoms.

In bivariate analysis, we also found a correlation between history of abuse and DSS at 1-year follow-up, which was similar to several other characteristics (i.e., age, alcohol consumption, depression, bowel symptoms, and use of gastric mucosa protectants, antacids and traditional Chinese medicine during 1 year follow-up period). However, this correlation was not found in multiple linear regression analysis, indicating that it was weak.

In conclusion, in this large sample of individuals with FD, 89.9% of patients completed all four follow-ups, and the average duration of follow-up was 12.24 ± 0.59 mo. During 1 year follow-up, the total DSS in FD patients showed a significant gradually reduced trend, and similar differences were found for all individual symptoms. Female sex, anxiety, sleep disorder, weight loss, consulting a physician, and prokinetic use during 1 year follow-up were associated with outcome. Our study described the fluctuations in symptoms and found that several associated factors affected outcome. We believe that these findings provide evidence for the role of psychosocial factors in determining long-term clinical course in patients with FD. In the future, more research is needed to confirm and extend our study.

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a chronic functional gastrointestinal disorder, and it has a significant impact on quality of life and imposes a substantial economic burden on society. However, the clinical course and risk factors for FD remain poorly studied.

In the present study, the authors selected a large group of FD patients from five cities in China and explored the clinical course and risk factors for FD both longitudinally and horizontally.

Some cross-sectional population studies have discovered several risk factors associated with FD. This is believed to be the first follow-up study showing that the total dyspeptic symptoms score and single symptom score in FD patients present a significant gradually reduced trend, and female sex, anxiety, sleep disorder, weight loss, consulting a physician, and prokinetic use during 1-year follow-up were associated with outcome.

The study described the fluctuations in dyspeptic symptoms and found several factors were associated with the outcome. This may provide evidence for the role of psychosocial factors in determining the long-term clinical course of patients with FD.

FD is a highly prevalent gastrointestinal disorder that is defined by the presence of symptoms thought to originate in the gastroduodenal region, without identifiable cause by routine diagnostic methods.

This is a follow-up study evaluating the clinical course and potential risk factors for FD. This is an interesting article discussing an important area in functional gastrointestinal disorders.

P- Reviewers Devanarayana NM, de la Roca-Chiapas JM S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, Holtmann G, Hu P, Malagelada JR, Stanghellini V. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466-1479. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Oustamanolakis P, Tack J. Dyspepsia: organic versus functional. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:175-190. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 76] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Camilleri M, Dubois D, Coulie B, Jones M, Kahrilas PJ, Rentz AM, Sonnenberg A, Stanghellini V, Stewart WF, Tack J. Prevalence and socioeconomic impact of upper gastrointestinal disorders in the United States: results of the US Upper Gastrointestinal Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:543-552. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Rezailashkajani M, Roshandel D, Shafaee S, Zali MR. A cost analysis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in Iran. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:412-417. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | El-Serag HB, Talley NJ. Systemic review: the prevalence and clinical course of functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:643-654. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Halder SL, Locke GR, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ, Talley NJ. Natural history of functional gastrointestinal disorders: a 12-year longitudinal population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:799-807. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Olafsdottir LB, Gudjonsson H, Jonsdottir HH, Thjodleifsson B. Natural history of functional dyspepsia: a 10-year population-based study. Digestion. 2010;81:53-61. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Van Oudenhove L, Demyttenaere K, Tack J, Aziz Q. Central nervous system involvement in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18:663-680. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Miwa H, Watari J, Fukui H, Oshima T, Tomita T, Sakurai J, Kondo T, Matsumoto T. Current understanding of pathogenesis of functional dyspepsia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26 Suppl 3:53-60. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Locke GR, Weaver AL, Melton LJ, Talley NJ. Psychosocial factors are linked to functional gastrointestinal disorders: a population based nested case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:350-357. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Van Oudenhove L, Vandenberghe J, Geeraerts B, Vos R, Persoons P, Fischler B, Demyttenaere K, Tack J. Determinants of symptoms in functional dyspepsia: gastric sensorimotor function, psychosocial factors or somatisation? Gut. 2008;57:1666-1673. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 145] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ford AC, Qume M, Moayyedi P, Arents NL, Lassen AT, Logan RF, McColl KE, Myres P, Delaney BC. Helicobacter pylori “test and treat” or endoscopy for managing dyspepsia: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1838-1844. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Jansson C, Nordenstedt H, Wallander MA, Johansson S, Johnsen R, Hveem K, Lagergren J. A population-based study showing an association between gastroesophageal reflux disease and sleep problems. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:960-965. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 68] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cremonini F, Camilleri M, Zinsmeister AR, Herrick LM, Beebe T, Talley NJ. Sleep disturbances are linked to both upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms in the general population. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:128-135. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lacy BE, Everhart K, Crowell MD. Functional dyspepsia is associated with sleep disorders. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:410-414. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 62] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, Spiller RC, Talley NJ, Thompson WG, Whitehead WE. Rome III-the functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3rd ed. Washington: Degnon 2006; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Talley NJ. Functional gastrointestinal disorders in 2007 and Rome III: something new, something borrowed, something objective. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2007;7:97-105. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Rome Foundation Diagnostic Algrithms. Rome III Psychosocial Alarm Questionnaire. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:796-797. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Zhu LM, Fang XC, Liu S, Zhang J, Li ZS, Hu PJ, Gao J, Xin HW, Ke MY. [Multi-centered stratified clinical studies for psychological and sleeping status in patients with chronic constipation in China]. Zhonghua Yixue Zazhi. 2012;92:2243-2246. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Ford AC, Forman D, Bailey AG, Axon AT, Moayyedi P. Initial poor quality of life and new onset of dyspepsia: results from a longitudinal 10-year follow-up study. Gut. 2007;56:321-327. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Ford AC, Forman D, Bailey AG, Axon AT, Moayyedi P. Fluctuation of gastrointestinal symptoms in the community: a 10-year longitudinal follow-up study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:1013-1020. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kindt S, Van Oudenhove L, Mispelon L, Caenepeel P, Arts J, Tack J. Longitudinal and cross-sectional factors associated with long-term clinical course in functional dyspepsia: a 5-year follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:340-348. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pajala M, Heikkinen M, Hintikka J. A prospective 1-year follow-up study in patients with functional or organic dyspepsia: changes in gastrointestinal symptoms, mental distress and fear of serious illness. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1241-1246. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Heikkinen M, Färkkilä M. What is the long-term outcome of the different subgroups of functional dyspepsia? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:223-229. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Van Oudenhove L, Tack J. New epidemiologic evidence on functional dyspepsia subgroups and their relationship to psychosocial dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:23-26. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | De la Roca-Chiapas JM, Solís-Ortiz S, Fajardo-Araujo M, Sosa M, Córdova-Fraga T, Rosa-Zarate A. Stress profile, coping style, anxiety, depression, and gastric emptying as predictors of functional dyspepsia: a case-control study. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68:73-81. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Koloski NA, Talley NJ, Boyce PM. Epidemiology and health care seeking in the functional GI disorders: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2290-2299. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Aro P, Talley NJ, Ronkainen J, Storskrubb T, Vieth M, Johansson SE, Bolling-Sternevald E, Agréus L. Anxiety is associated with uninvestigated and functional dyspepsia (Rome III criteria) in a Swedish population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:94-100. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 184] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tack J, Jones MP, Karamanolis G, Coulie B, Dubois D. Symptom pattern and pathophysiological correlates of weight loss in tertiary-referred functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:29-35, e4-5. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lu CL, Lang HC, Chang FY, Chen CY, Luo JC, Wang SS, Lee SD. Prevalence and health/social impacts of functional dyspepsia in Taiwan: a study based on the Rome criteria questionnaire survey assisted by endoscopic exclusion among a physical check-up population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:402-411. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Hsu PI, Lai KH, Lo GH, Tseng HH, Lo CC, Chen HC, Tsai WL, Jou HS, Peng NJ, Chien CH. Risk factors for ulcer development in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia: a prospective two year follow up study of 209 patients. Gut. 2002;51:15-20. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Jones R, Liker HR, Ducrotté P. Relationship between symptoms, subjective well-being and medication use in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61:1301-1307. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Hansen JM, Wildner-Christensen M, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB. Gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in a Danish population: a prospective follow-up analysis of symptoms, quality of life, and health-care use. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2394-2403. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |