Published online May 28, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i20.3147

Revised: July 6, 2004

Accepted: September 4, 2004

Published online: May 28, 2005

AIM: To investigate the effect of emodin on small intestinal peristalsis of mice and to explore its relevant mechanisms.

METHODS: The effect of emodin on small intestinal peristalsis of mice was observed by charcoal powder propelling test of small intestine. The contents of motilin and somatostatin in small intestine of mice were determinated by radioimmunoassay. The electrical potential difference (PD) related to Na+ and glucose transport was measured across the wall of reverted intestinal sacs. Na+–K+-ATPase activity of small intestinal mucosa was measured by spectroscopic analysis.

RESULTS: Different dosages of emodin can improve small intestinal peristalsis of mice. Emodin increased the content of motilin, while reduced the content of somatostatin in small intestine of mice significantly. Emodin 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, and 1.6 g/L decreased PD when there was glucose. However, emodin had little effect when glucose was free. The Na+–K+-ATPase activity of small intestinal mucosa of mice in emodin groups was inhibited obviously.

CONCLUSION: Emodin can enhance the function of small intestinal peristalsis of mice by mechanisms of promoting secretion of motilin, lowering the content of somatostatin and inhibiting Na+–K+-ATPase activity of small intestinal mucosa.

- Citation: Zhang HQ, Zhou CH, Wu YQ. Effect of emodin on small intestinal peristalsis of mice and relevant mechanism. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(20): 3147-3150

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i20/3147.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i20.3147

Rhubarb has been used to treat gastrointestinal disorders for hundreds of years. The effective components of rhubarb are anthraquinone derivatives, emodin being the most important. Traditional viewpoints hold that emodin primarily acts on the large intestine and it can enhance the excitability of smooth muscles of the large intestine[1,2]. We have obtained more than 95% pure emodin from China Pharmaceutical University In this study, we evaluated whether emodin had any effects on small intestinal peristalsis of mice and explored its relevant mechanisms.

Animals and treatment[3]

Fifty healthy ICR mice (weighing 18-22 g) were randomly divided into five groups: normal control, model, low dose of emodin, medium dose of emodin and high dose of emodin. The animals in emodin treatment groups and model group were put through intragastric gavage (IG) with compound diphenoxylate 0.2 mL/10 g. Those in normal control were treated with NS. Thirty minutes later different medications were given: mice in normal control and model group were given NS, and those in emodin treatment groups were given emodin 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4 g/kg respectively. All of the animals were administered as above for 1 wk and were fasted for 12 h before the last administration.

Charcoal powder propelling test of small intestine[4]

Thirty minutes after the last administration, all animals were IG charcoal powder suspended liquid 0.2 mL/10 g. Twenty minutes later the mice were killed by exarticulation. The small intestine from pylorus to the boundary of ileum and cecum was isolated and its length was “total length of small intestine”. The length from pylorus to the foreland of charcoal powder was “charcoal powder propelling length”.

Charcoal powder propelling ratio=[charcoal powder propelling length (cm)/total length of small intestine(cm)]×100%.

Fifty mice were administered as above. Thirty minutes after the last administration, the small intestinal tissues were treated according to Sun et al[5]. The contents of motilin and somatostatin in small intestine of mice were determined by radioimmunoassay according to the protocols of the kit.

After isolating small intestinal tissues, the mice above were intercepted between 5 cm intestinal segments below the Treitz ligament. The intestines were rinsed repeatedly by NS and made into homogenates of small intestinal mucosa. The Na+–K+-ATPase activity of small intestinal mucosa was measured by spectroscopic analysis according to the protocols of the kit. The protein was determined by Coomassie Brilliant Blue Method. The unit of Na+–K+-ATPase activity was μmol pi/mg Pro/h.

Potential difference (PD) of isolated small intestine[6,7]

About 8 cm of jejunum was taken, and cleaned with K-H solution. The wall of intestinal sacs was reverted. We ligated one end, and the other end was tied with tubuliform glass-tube. The reverted intestinal sac full of K-H solution was put in a tube full of 25 mmol/L glucose K-H solution (glucose K-H) or glucose-free K-H (at 37 °C). The mixed gas including 50 mL/L CO2 and 95% O2 was injected. The electrical potential difference (PD) was measured across the wall of reverted intestinal sacs. The drugs in experiment were dissolved by glucose-free KH or glucose KH, PH was regulated and the osmotic pressure was modulated with mannitol. PD was recorded every 2.5 min and observed 15 min continuously.

All data were expressed as mean±SD. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired t test. Differences were considered significant when P≤0.05.

The charcoal powder propelling ratio in normal control was 56.4±4.9%, while it greatly decreased to 44.7±10.3% in model group. Comparing with model group, emodin 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4 g/kg induced obvious increase of the charcoal powder propelling ratio of small intestine, and reached 54.6±6.6%, 67.2±18.4%, and 70.6±10.1%, respectively (Table 1).

Comparing with normal control, the content of motilin was lower while the content of somatostatin was higher in model group (P<0.01). After treatment with different doses of emodin, the content of motilin increased (P<0.05, P<0.01), while that of somatostatin decreased significantly (P<0.05, P<0.01) (Figure 1).

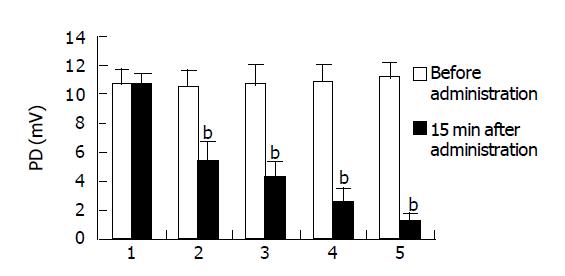

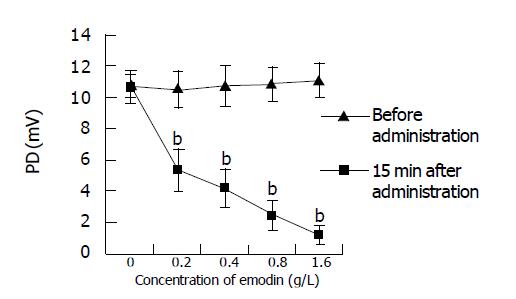

Effect of glucose K-H and different concentrations of emodin on PD of isolated small intestine Before administration vs after administration: Fifteen minutes after administration of 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, and 1.6 g/L of emodin can lower PD of isolated small intestine of mice significantly (P<0.01) (Figure 2); compared between different groups: there was no significant difference between every group before administration. Fifteen minutes after administration of 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, and 1.6 g/L of emodin can lower PD of isolated small intestine of mice significantly, compared to K-H solution group, there were significant differences (P<0.01), which indicated that 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, and 1.6 g/L of emodin can lower PD of isolated small intestine of mice significantly, and, the inhibitory effect enhanced with increasing concentration (Figure 3).

Effect of glucose-free K-H and different concentration of emodin on PD of isolated small intestine There are no significant differences in comparison between the same group before administration and 15 min after administration. The results indicated that emodin dissolved by glucose-free K-H had no evident inhibitory effect on PD of isolated small intestine (Table 2).

| Group | Concentration (g/L) | PD (mV) | |

| Before administration | 15 min after administration | ||

| K-H solution | 2.43±0.43 | 2.25±0.39 | |

| Emodin | 0.2 | 2.15±0.58 | 2.02±0.50 |

| 0.4 | 2.42±0.40 | 2.28±0.52 | |

| 0.8 | 2.55±0.34 | 2.52±0.32 | |

| 1.6 | 2.38±0.21 | 2.23±0.27 | |

Effect of emodin on the activity of Na+–K+-ATPase in small intestinal mucosa of mice The activity of Na+–K+-ATPase in small intestinal mucosa of mice was higher significantly in model group than that in normal control (P<0.01). In emodin treatment groups the activity of Na+–K+-ATPase in small intestinal mucosa of mice decreased prominently (P<0.05, P<0.01) (Table 3).

Rhubarb is one of the most frequently used evacuants in clinic. Emodin is one of the primary components of rhubarb. Emodin is thought to be acting mainly on the large intestine[8-11]. In this study, we have attempted to investigate the effect of emodin on small intestinal peristalsis of mice and to explore its relevant mechanisms.

We observed the effect of emodin on charcoal powder propelling movement of small intestine in mice. The result showed that emodin increased the charcoal powder propelling ratio of small intestine, which indicates that emodin can enhance the function of small intestinal peristalsis of mice.

Motilin, which is made up of 22 amino acids, has long been recognized as an important endogenous peptide regulator of gastrointestinal motor function. Motilin is secreted by M0 cells distributing in the recess of mucosa in duodenum and jejunum[12-14]. In the interphase of digestion, motilin is secreted with periodicity. Motilin can touch off the occurrence of three phases of migrating motor complex (MMC) through acting on the motilin nerve cells in the nervous system of intestinal tract, which arouses the intense constriction of stomach and segmentation contraction of small intestine. The punchy contractive wave of three phases of MMC extended to a distance along the small intestine at the rate of 5-10 cm/min. And when it passes through the gastrointestinal tract, it can clean up the contents of gastrointestine including the alimentary residue of last diet, cellular fragment falling off and bacteria. So motilin is a street sweeper[15]. Motilin plays an important role in regulation of gastrointestinal movement by touching off the occurrence of three phases of MMC. In our study we found that the content of motilin in small intestine of mice in model group was lower than that in normal control, and after treatment with emodin, the content of motilin was increased at different degree. So emodin can enhance the function of small intestinal peristalsis of mice by promoting secretion of motilin.

Somatostatin distributed in the gastrointestinal tract diffusely. Somatostatin can inhibit gastrointestinal function by two ways: one is by inhibiting the activity of adenylyl cyclase through inhibitory G protein; the other is by inhibiting the release of cholinergic neurotransmitter[16-19]. The result of this study showed that the content of somatostatin in small intestine of mice was increased significantly comparing with normal control. Different dosages of emodin could inhibit the secretion of the somatostatin prominently. This may be another mechanism of emodin to promote the movement of small intestine.

Some electrolyte can get across the epithelium of small intestine by active transport or passive transport, which leads to electrical potential difference (PD) between mucous membrane and chorion of small intestine. When it was adjusted to zero, passive transport of electrolyte was inhibited, while active transport continued. Then the change of PD between mucous membrane and chorion of small intestine reflected the change of active transport[20]. Glucose absorption in small intestine mucous membrane was completed by active transport. Active transport needs to consume energy, the main substance supplying energy is Na+–K+-ATPase[21,22]. So the decrease of active transport of ion indicated that Na+–K+-ATPase may be inhibited.

In this study we used high glucose K-H solution in order to study the role of glucose accompanied Na+-transportation, which leads to PD maintaining a steady high level, contributing to eliminate interference of organic component in drugs to PD. In order to study glucose-non-dependent Na+-transportation, we used glucose-free K-H to observe the change of simple Na+-transportation PD. We found that when glucose existed, different doses of emodin could lower PD significantly. On the contrary, when glucose was absent, emodin had no evident effect on PD. The above results indicated that emodin had no significant effect on simple Na+-transportation PD, it mainly inhibited the active transportation of Na+, especially inhibited glucose-dependent Na+-transportation.

Sodium pump is Na+–K+-ATPase in substance. One ATP molecule breaking down, there are three sodium ions moving out of the cell membrane and two potassium ions moving into the cell membrane at the same time. By this way a potential energy reservoir is established, which is in favor of the transmembrane transportation. The absorption of glucose and amino acid by intestinal mucosa is just through this secondary active transport[23-25]. When the activity of Na+–K+-ATPase in intestinal mucosa is reduced, the potential energy reservoir is lessened. And the absorption of glucose, amino acid and sodium ions by intestinal tract is decreased too, which results in the enhancement of the osmotic pressure in enteric cavity and the peristalsis of intestinal tract which is fortified and quickened subsequently[22]. Our study indicated that the the activity of Na+–K+-ATPase in intestinal mucosa in emodin treatment groups was decreased prominently comparing with that in model group. The decrease of the activity of Na+–K+-ATPase in intestinal mucosa may be also one of the mechanisms for emodin to accelerate the movement of small intestine.

In conclusion, emodin can enhance the function of small intestinal peristalsis of mice and its mechanisms may be relevant to promoting secretion of motilin, lowering the content of somatostatin and inhibiting Na+–K+-ATPase activity of small intestinal mucosa.

Science Editor Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Shen YJ. Pharmacology of traditional Chinese medicine.1th ed. Beijing: People’s health publication 2002; 329-330. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Kai M, Hayashi K, Kaida I, Aki H, Yamamoto M. Permeation-enhancing effect of aloe-emodin anthrone on water-soluble and poorly permeable compounds in rat colonic mucosa. Biol Pharm Bull. 2002;25:1608-1613. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wan JZ. One kind of simple constipation model of mice. Chin Pharmacol Bull. 1994;10:71-72. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Chen Q. Methodology of pharmacology of traditional Chinese medicine.1th ed. Beijing: People’s health publication 1993; 331-335. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Sun WF, Xu W, Wang XC, Wei S, Luo XY, Xiao DY. Effect of Shengjiang Decoctinon on gastrointestinal peristalsis and gastrointestinal hormones of mice. J Anhui TCM College. 2002;21:45-47. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Jia B, Gu XL, Zhang SQ. The effect of chinese traditional medicine additive on glucose absorption of isolated small intestine. Livestock And Poultry Industry. 1998;12:15-16. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Cui ZQ, Guo SD, Ye B, Zhang HR. The effect of taurine on transmural potential of mouse small intestine in vitro. Chinese Pharmacol Bulletin. 1995;11:288-290. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Iizuka A, Iijima OT, Kondo K, Itakura H, Yoshie F, Miyamoto H, Kubo M, Higuchi M, Takeda H, Matsumiya T. Evaluation of Rhubarb using antioxidative activity as an index of pharmacological usefulness. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;91:89-94. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 55] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ding M, Ma S, Liu D. Simultaneous determination of hydroxyanthraquinones in rhubarb and experimental animal bodies by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Sci. 2003;19:1163-1165. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhao J, Chang JM, Du NS. Studies on the chemical constituents in root of Rheum rhizastachyum. Zhongguo ZhongYao ZaZhi. 2002;27:281-282. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Shang XY, Yuan ZB. Determination of six effective components in Rheum by cyclodextrin modified micellar electrokinetic chromatography. Yaoxue Xuebao. 2002;37:798-801. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Peeters TL. Central and peripheral mechanisms by which ghrelin regulates gut motility. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;54 Suppl 4:95-103. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Delinsky DC, Hill KT, White CA, Bartlett MG. Quantitative determination of the polypeptide motilin in rat plasma by externally calibrated liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2004;18:293-298. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Qi QH, Wang J, Hui JF. Effect of dachengqi granule on human gastrointestinal motility. Zhongguo ZhongXiYi JieHe ZaZhi. 2004;24:21-24. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Yao T. Physiology. 5th ed. Beijing: People’s Health Publication 2002; 188-190. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Peeters TL, Muls E, Janssens J, Urbain JL, Bex M, Van Cutsem E, Depoortere I, De Roo M, Vantrappen G, Bouillon R. Effect of motilin on gastric emptying in patients with diabetic gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:97-101. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Leandros E, Antonakis PT, Albanopoulos K, Dervenis C, Konstadoulakis MM. Somatostatin versus octreotide in the treatment of patients with gastrointestinal and pancreatic fistulas. Can J Gastroenterol. 2004;18:303-306. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | de Franchis R. Somatostatin, somatostatin analogues and other vasoactive drugs in the treatment of bleeding oesophageal varices. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36 Suppl 1:S93-100. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Konturek PC, Konturek SJ. The history of gastrointestinal hormones and the Polish contribution to elucidation of their biology and relation to nervous system. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;54 Suppl 3:83-98. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Kitaoka S, Hayashi H, Yokogoshi H, Suzuki Y. Transmural potential changes associated with the in vitro absorption of theanine in the guinea pig intestine. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1996;60:1768-1771. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cereijido M, Shoshani L, Contreras RG. The polarized distribution of Na+, K+-ATPase and active transport across epithelia. J Membr Biol. 2001;184:299-304. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhou XM, Chen QH. Biochemical study of Chinese rhubarb. XXII. Inhibitory effect of anthraquinone derivatives on Na+-K+-ATPase of the rabbit renal medulla and their diuretic action. YaoXue XueBao. 1988;23:17-20. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Laughery M, Todd M, Kaplan JH. Oligomerization of the Na,K-ATPase in cell membranes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:36339-36348. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ukkola O, Joanisse DR, Tremblay A, Bouchard C. Na+-K+-ATPase alpha 2-gene and skeletal muscle characteristics in response to long-term overfeeding. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2003;94:1870-1874. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Horvath G, Agil A, Joo G, Dobos I, Benedek G, Baeyens JM. Evaluation of endomorphin-1 on the activity of Na(+),K(+)-ATPase using in vitro and in vivo studies. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;458:291-297. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |