Copyright

©The Author(s) 2015.

World J Gastroenterol. May 7, 2015; 21(17): 5231-5241

Published online May 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i17.5231

Published online May 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i17.5231

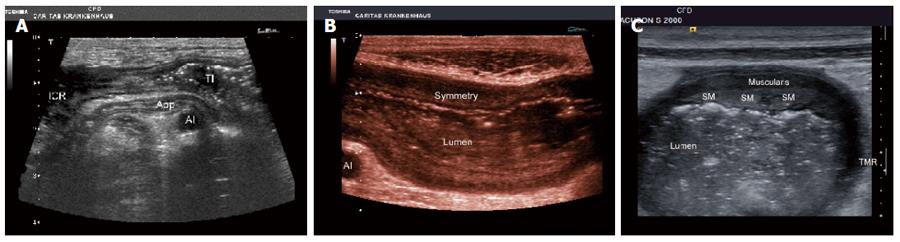

Figure 1 Crohn’s disease of the ileocecal region with stenosis of the terminal ileum.

A: The normal appendix is shown as well (APP) crossing the iliacal vessels; B: Crohn’s disease of the terminal ileum. Note the symmetric thickening of the bowel wall. AI: Iliacal vessels; Crohn’s disease of the sigmoid colon. Note the asymmetric and segmental thickening of the antimesenteric bowel wall mainly focussed on the submucosal layer (SM); C: Muscularispropria and the lumen are also indicated. TMR: Transmural reaction.

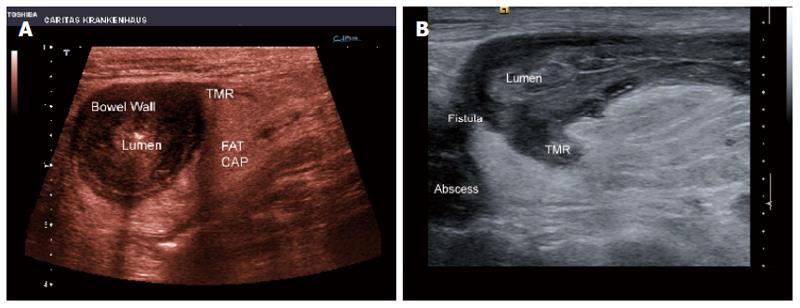

Figure 2 Segmental Crohn’s disease.

Note the “dirty” bowel wall thickening with loss of layer structure and the transmural inflammation without fistula and abscess formation. A: The periintestinal inflammatory reaction is shown by surrounding tissue (FAT CAP) (A). Crohn’s disease; B: Note the transmural inflammation (TMR) with fistula and abscess formation. The lumen is also indicated.

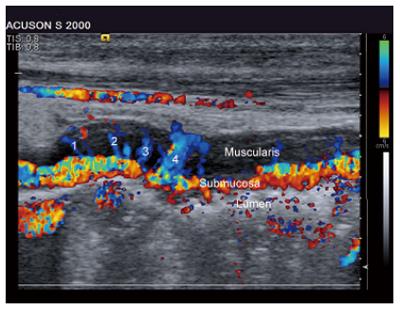

Figure 3 Crohn’s disease.

Colour Doppler imaging has been used to determine disease activity. Note the vessels (1-4) transversing the muscle proper layer (Muscularis). The lumen and the vessels within the submucosal layer are also indicated.

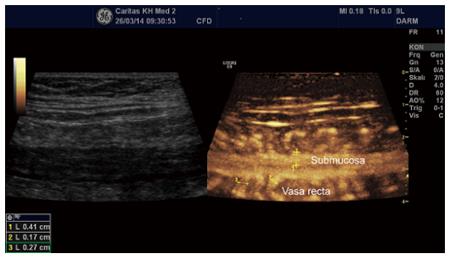

Figure 4 Colitis.

Contrast enhanced ultrasound of the submucosal layer (in between markers “1”) (to the right). The vasa recta transversing the muscle proper layer. CEUS has been also used to determine disease activity.

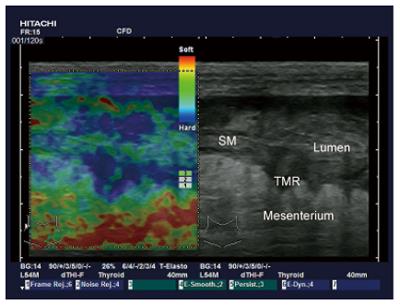

Figure 5 Strain imaging techniques allow noninvasive imaging of the mechanical characteristics of inflamed tissue.

The mesenterium and lumen are also indicated. SM: Submucosal layer. TMR: Transmural inflammatory reaction.

- Citation: Chiorean L, Schreiber-Dietrich D, Braden B, Cui XW, Buchhorn R, Chang JM, Dietrich CF. Ultrasonographic imaging of inflammatory bowel disease in pediatric patients. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(17): 5231-5241

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i17/5231.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i17.5231