Copyright

©2008 The WJG Press and Baishideng.

World J Gastroenterol. Jan 7, 2008; 14(1): 22-28

Published online Jan 7, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.22

Published online Jan 7, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.22

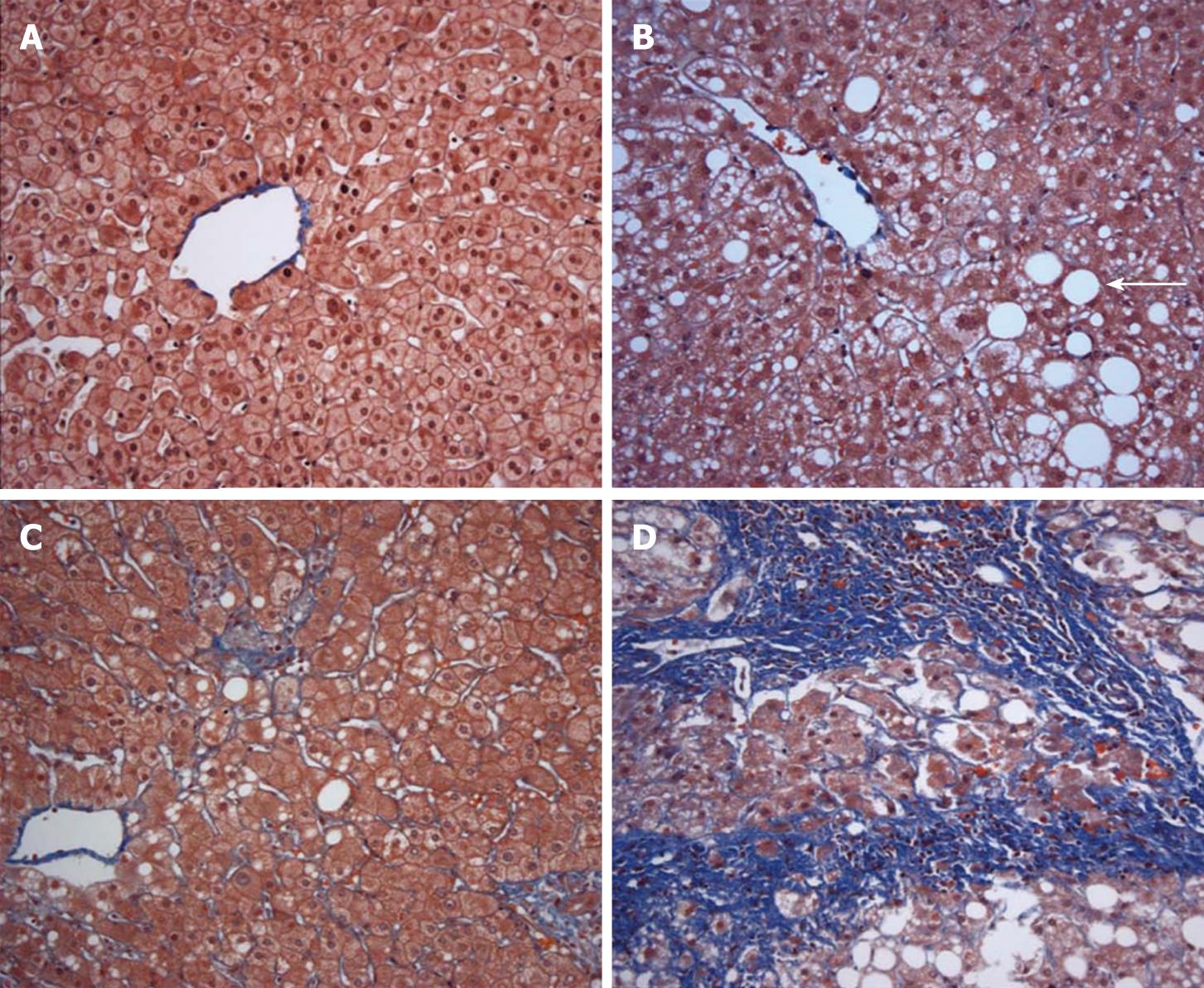

Figure 1 Liver histology ranging from normal liver to steatohepatitis with fibrosis.

A: Normal liver. Cytoplasmic fat globules are absent in hepatocytes and there is no fibrosis in this trichrome stained specimen (× 20); B: Steatosis without steatohepatitis. Moderate cytoplasmic fat infiltration (arrow) is present without fibrosis (× 20); C: Steatohepatitis with minimal fibrosis. There is focal hepatocyte ballooning, inflammation, and minimal fibrosis (accentuated in blue by trichrome stain); D: Steatohepatitis with fibrosis. There is nodular scarring in this fat laden liver with advanced fibrosis depicted in blue by trichrome stain (× 20).

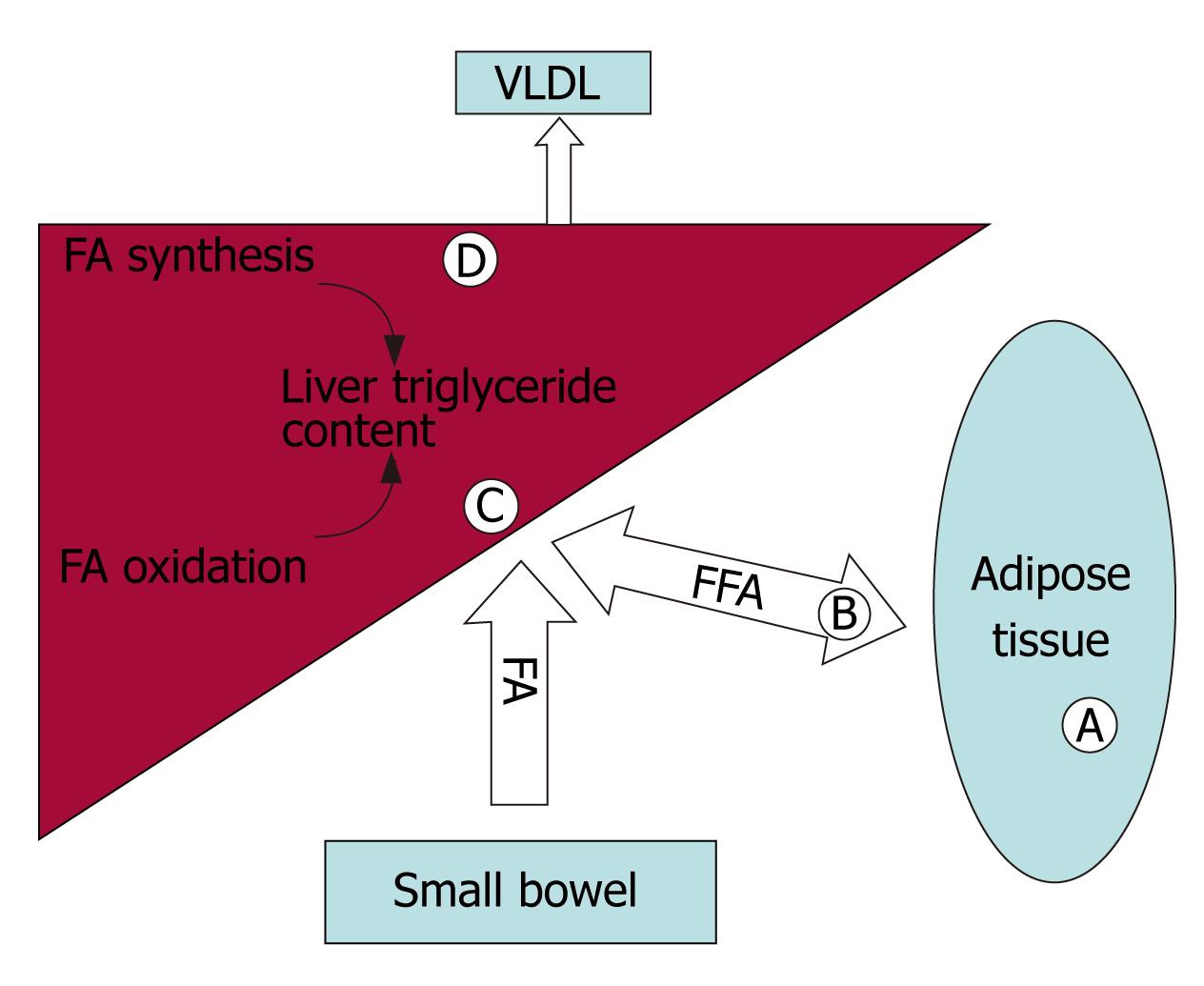

Figure 2 Mechanisms by which PPARs and their ligands can modulate triglyceride accumulation are highlighted by letters in the figure.

A: PPARγ increases expression of genes associated with fatty acid uptake and triglyceride storage in adipocytes. Release of adiponectin from adipocytes improves insulin sensitivity and activates PPARα; B: PPARγ increases lipoprotein lipase expression, liberating circulating fatty acids from lipoproteins for import into adipocytes; C: PPARα activity up regulates β-oxidation of fatty acids in the liver; D: PPARα and TZDs upregulate stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1, a necessary enzyme for VLDL synthesis and export, and TZDs increase arachidonic acid content in triglycerides, which is associated with increased insulin sensitivity.

- Citation: Kallwitz ER, McLachlan A, Cotler SJ. Role of peroxisome proliferators-activated receptors in the pathogenesis and treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(1): 22-28

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i1/22.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.22