Copyright

©2006 Baishideng Publishing Group Co.

World J Gastroenterol. Oct 21, 2006; 12(39): 6261-6265

Published online Oct 21, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i39.6261

Published online Oct 21, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i39.6261

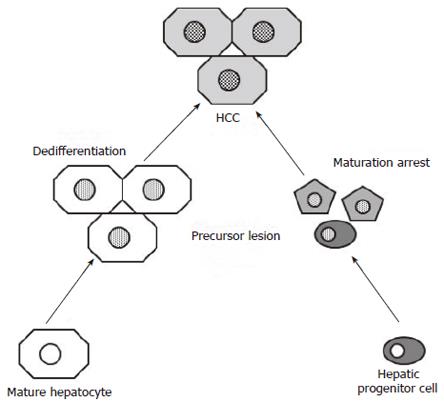

Figure 1 Schematic representation of the “maturation arrest” hypothesis and the “dedifferentiation” hypothesis applied to hepatocellular carcinoma and its precursor lesions.

According to the “maturation arrest” hypothesis, genetic alterations (grid in nuclei) occurring in hepatic progenitor cells causes proliferation and incomplete differentiation of these cells, eventually leading to hepatocellular carcinomas that express hepatic progenitor cell markers (grayscale) as an evidence of their cellular origin. In this scenario, precursor lesions contain hepatic progenitor cells and intermediate cells (the small polygonal cells). The “dedifferentiation” hypothesis states that the expression of hepatic progenitor cell markers in hepatocellular carcinoma is merely a result of tumor progression and consequently the precursor lesions should only consist of mature hepatocytes.

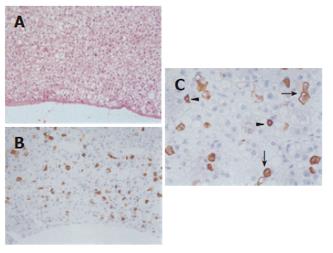

Figure 2 Hematoxylin-eosin stained section of a hepatocellular carcinoma, which suggests that the tumor consists of mature hepatocytes (A).

However, the staining for the hepatic progenitor cell marker cytokeratin 7 (B and C) shows the presence of hepatic progenitor cells (arrowheads) and intermediate hepatocyte-like cells (arrows) distributed in a “starry sky” pattern against a background of mature hepatocytes. Original magnification: x 100 (A and B) and x 200 (C).

- Citation: Libbrecht L. Hepatic progenitor cells in human liver tumor development. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(39): 6261-6265

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i39/6261.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i39.6261