Published online Oct 26, 2017. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v5.i5.124

Peer-review started: January 22, 2017

First decision: March 8, 2017

Revised: May 5, 2017

Accepted: June 30, 2017

Article in press: July 1, 2017

Published online: October 26, 2017

To examine the efficacy and safety of thalidomide and thalidomide analogues in induction and maintenance of remission in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

A literature search was performed in the following databases: PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Ovid and the Cochrane Library, and Chinese databases such as the China National Knowledge Infrastructure, China Science and Technology Journal Database (VIP), Wanfang Data. The randomized controlled analysis was performed to assess the effects of thalidomide therapy on inflammatory bowel disease for patients who did show good response with other therapies.

Three studies (n = 212) met the inclusion criteria were used in this Meta-analysis. No difference was found between thalidomide/thalidomide analogues and placebo in the induction of remission (RR = 1.36, 95%CI: 0.83-2.22, P = 0.22), the induction of clinical response (RR = 1.14, 95%CI: 0.75-1.72, P = 0.54) and the induction of adverse events (RR = 1.41, 95%CI: 0.99-2.02, P = 0.06).

Currently, there is not enough evidence to support use of thalidomide or its analogue for the treatment in patients of any age with IBD. However, it warrants a reanalysis when more data become available.

Core tip: The aim of this meta-analysis is to examine the efficacy and safety of thalidomide and thalidomide analogues for induction and maintenance of remission in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The literature was searched in the databases: PubMed, EMBASE, Ovid and the Cochrane Library, and Chinese databases. The Randomized Controlled Trials was performed during this analysis to assess the effects of thalidomide therapy on IBD patients that did show good response with other therapies. Weighted pooled outcomes were synthesized with a fixed-effects model to account for clinical heterogeneity. This meta-analysis showed that there is not enough evidence to support the use of thalidomide or its analogues in the treatment of IBD for patients of any age.

- Citation: Sami Ullah KR, Xiong YL, Miao YL, Ummair S, Dai W. Thalidomide and thalidomide analogues in treatment of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Meta-analysis. World J Meta-Anal 2017; 5(5): 124-131

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v5/i5/124.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v5.i5.124

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is characterized by chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract with the long period of clinical relapse and remission[1]. Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are two main subtypes of inflammatory bowel diseases[1]. The quality of life of the patients who are suffering from IBD is highly affected. The causes of IBD are still unclear but many researchers believe that environmental factors and microbial triggers might induce IBD[2,3].

The prevalence of IBD varies considerably around the world with diagnostic criteria vary between geological regions. It is believed that IBD is associated with increased industrialization of countries. The highest prevalence of IBD is observed in North America and Europe[4] (2.6 million in Europe and 1.2 million in North America)[5,6].

There is no cure of IBD to date, aims of the therapy are induction and maintenance of remission[1,2]. Corticosteroids are the mostly used drugs, which shows effectiveness but only in, inducing remission but not in maintenance of remission for IBD[7,8].

There are many drugs that have been used in the treatment of IBD, however, maintaining remission remains a challenge. A safe and effective drug for the treatment of IBD remains to be found Thalidomide was initially used as a sedative and antiemetic drug. It was removed from the market during 1960s because it births related defects[9].

It was discovered later that thalidomide could inhibit the synthesis of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) by accelerating the degradation of its mRNA[10]. The immune regulatory property of thalidomide raised peoples’ interests in its potential for the treatments of autoimmune diseases in recent years. The efficacy of thalidomide treatment has been demonstrated by a series of clinical trials in a serious clinical disease like human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) associated wasting syndrome, hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia[11], refractory cutaneous lesion of lupus erythematous[12], multiple myeloma[13], and Bachet’s disease[14].

The increased production of TNF-α in IBD plays a major role in the pathophysiology of IBD[15,16] and TNF-α tends to increase with the disease progression[13,14].

The development of thalidomide analogues was spurred due to emerging clinical evidence supports that the drug has anti-angiogenic and anti-inflammatory properties[17]. So far there have been many thalidomide analogues but the most famous ones are Lenalidomide, Pomalidomide and Apremilast. They all work is similar manner and have similar mechanisms for the treatment of diseases It is believed that they work by different mechanisms in different diseases[18,19]. Apremilast works differently by reducing PDE4 activity and causing an increase in cAMP concentrations, which lead to inhibition of many pro-inflammatory cytokines and increased production of anti-inflammatory cytokines[20]. Literature review shows no evidence to support or deny the use of thalidomide analogues for the treatment of IBD, nor does it show any difference in efficacy compared with thalidomide.

In a Cocranine review of thalidomide analogues for the induction of remission and maintenance of of Crohn’s disease, lenalidomide showed no statistically significant benefits over placebo[21,22].

Thalidomide has the property to suppressing the synthesis of TNF-α[23,24]. Thalidomide can reduce the production of TNF-α by lipopolysaccharide or phytohaemaglutinin-stimulated monocytes and macrophages and mitogen-induced T-cells[25,26]. Although the exact mechanisms by which TNF-α involves in diseases is not clear, thalidomide seems to be effective for the treatment of diseases[10].

The aim of this study was to systematically review the current evidence examining the efficacy and safety of thalidomide and thalidomide analogues for the induction and maintenance of remission in patients with IBD.

Two authors (Khan Rana Sami Ullah and Yu-Lin Xiong) independently carried out a retrieval of literatures that investigated the association between thalidomide or thalidomide analogues and IBD. A literature search was performed in the following databases: PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Ovid and the Cochrane Library, and chinese databases including the China National Knowledge Infrastructure, China Science and Technology Journal Database, Wanfang Data. The Medical Subject Terms (MeSH) and Keywords used for this research were: Thalidomide OR lenalidomide AND “inflammatory bowel disease” OR “Crohn’s disease” OR “Ulcerative colitis”. The last search was performed on April 20, 2015. We performed a further manual search of references from original or review articles on this topic.

The titles and abstracts of published studies were screened independently by two authors (Khan Rana Sami Ullah and Yu-Lin Xiong)to determine whether they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) randomized controlled trials (RCTs), assessed the efficacy and safety of thalidomide and thalidomide analogues for treating patients with IBD, including UC and CD; (2) participants: Patients with IBD of all age groups, including UC and CD; (3) intervention: Thalidomide and thalidomide analogues (any route, dose, duration); (4) provided sufficient data for estimation of a relative risk (RR) and corresponding 95%CI; and (5) published in the English or Chinese language.

The methodological quality of selected trials was assessed independently by two authors (Khan Rana Sami Ullah and Yu-Lin Xiong) using the criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions[27] and the Jadad scale[28]. The former is based on the evidence of a strong relationship between allocation concealment and direction of effect. The Jadad scale is a validated five point, scale which measures some important factors that impact on the quality of a trial. They are summarized below: (1) was the study described as randomized? (2) was the method of randomization well described and appropriate? (3) was the study described as double blind? (4) was the double blinding well described and appropriate? and (5) were the withdrawals and dropouts described?

A data extraction form was developed and used to extract information on relevant features and results of included studies. The two authors (Khan Rana Sami Ullah and Yu-Lin Xiong) independently extracted and recorded data on the predefined checklist. Differences were resolved by discussion. Extracted data included the following items (Tables 1 and 2): (1) characteristics of patients: Author, publish year, age, sex, country, participants, duration of therapy; (2) total number of patients originally assigned to each intervention group; (3) intervention: Thalidomide, Lenalidomide; (4) control: No intervention, placebo or other interventions; and (5) outcomes: Primary outcome: Clinical remission as defined by the primary studies and expressed as a percentage of patients with Secondary outcomes: Clinical response as defined by the primary studies, and adverse events.

| Study/yr | Country | Patients No. (intervention/control) | Mean age (intervention/control) | Gender (male/female) | Participants |

| Luo/2008 | China | 23/23 | 37.2/36.5 | 27/19 | Aged 18 to 70 yr, with mild-to-moderate CD |

| Lazzerini/2013 | Italy | 28/26 | 14.0/15.0 | 32/22 | Aged 2 to 18 yr with active CD |

| Mansfield/2007 | United Kingdom | 23/28 | 41.5/41.3 | 21/30 | Aged 18 to 75 yr with moderately severe CD |

| 33/28 | 37.5/41.3 | 33/29 |

| Study/yr | Intervention | Control | Remission (intervention/control) | Response (intervention/control) | Adverse effects (intervention/control) |

| Luo/2008 | Thalidomide100 mg/d | SASP | 6/5 | 15/13 | 10/9 |

| 4 g/d | |||||

| Lazzerini/2013 | Thalidomide 50, 100 and 150 mg/d | Unknown | 3/13 | 5/5 | Unknown/1 |

| Mansfield/2007 | lenalidomide 25 mg ⁄d, | Unknown | 2/7 | 4/4 | 10/18 |

| lenalidomide 5 mg ⁄d | 10/7 | 6/4 | 12/10 |

The Cochrane Collaboration review manager software (RevMan version 5.0) was used for data analysis. Results were analyzed according to the intention-to-treat principle. We assessed the efficacy and safety of thalidomide and thalidomide analogues for treating patients with IBD by calculating the pooled RR and corresponding 95%CI using meta-analysis. The Cochrane Q-test was used to evaluate the heterogeneity among those studies. I2 was used to quantify the size of heterogeneity. When there was no significant heterogeneity (I2 < 50%), we used the fixed-effects model to analyze the data. Otherwise, we used the random-effects model. In this study, we performed a sensitivity analysis to test the stability of results. Patients with final missing outcomes were assumed to be treatment failures. Funnel plots were not conducted to investigate publication bias as there were not enough studies included in each comparison to produce a meaningful analysis.

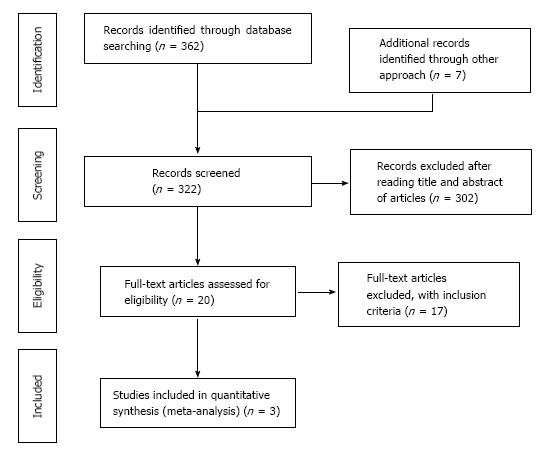

The above described search strategy identified 362 citation. There was also additional references added through other approach (7 articles), and the total number of articles used for literature review was 369 (362 + 7). Out of these 369 articles, 47 duplicates were removed, leaving only 322 primary articles (369 - 47 = 322). Out of these 322 primary articles, 302 were excluded after reading titles and abstract of articles. The remaining 20 articles assessed the efficacy and safety of thalidomide and thalidomide analogues for treating patients with IBD, including UC and CD. Only 3 out of the 20 articles were used for the meta-analysis as 17 failed to meet the inclusion criteria. The process of the included articles were shown Figure 1.

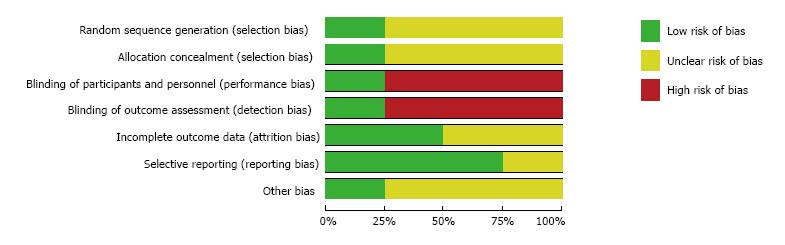

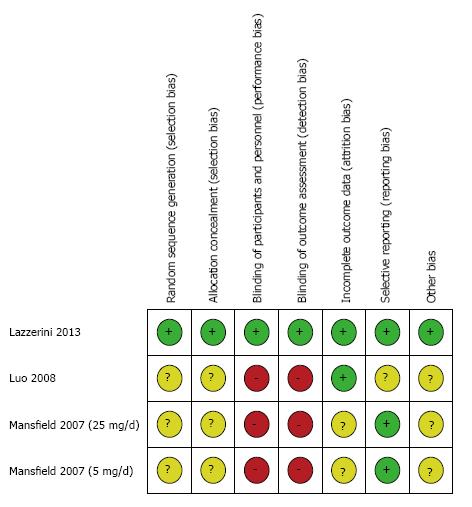

The assessment of the risk of bias for the three studies used in the meta-analysis was summarized in Figures 2 and 3. Overall, the Lazzerini’s study[29] has high quality (Jadad score = 5). The two studies[30,31] were rated as having high risk of bias (Jadad score = 3) due to not providing sufficient information on the method of randomization and lack of proper blinding controls. All data were analyzed based on the intention-to-treat principle. Due to an insufficient number of studies to produce a meaningful analysis, funnel plots were not used to investigate publication bias.

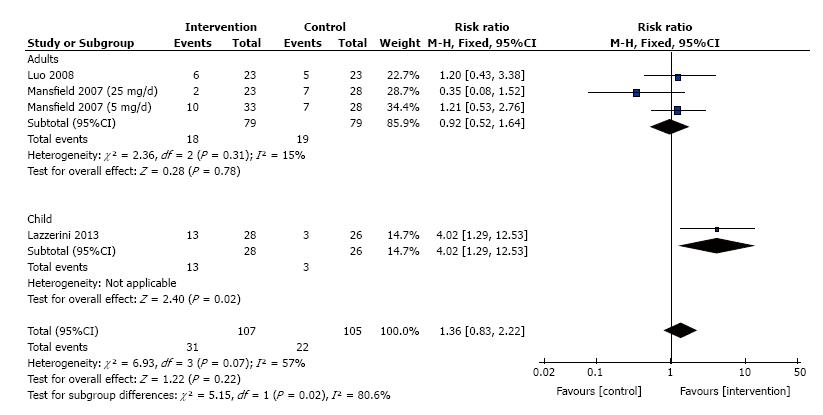

The frequency of induction of remission for patients treated with thalidomide was studied in 3 trials that consisted of 212 patients. Significant heterogeneity was detected between these trials (I2 = 57%, P = 0.07). We divided these trials into two subgroups (adults and children), and no significant heterogeneity was detected in the adult’s trials (I2 = 15%, P = 0.31). No meta-analysis was performed for Children’s IBD as there was only one trial available. Meta-analysis using a fixed effects model showed no difference between thalidomide and placebo for the maintenance of clinical remission (RR = 1.36, 95%CI: 0.83 - 2.22, P = 0.22; Figure 4).

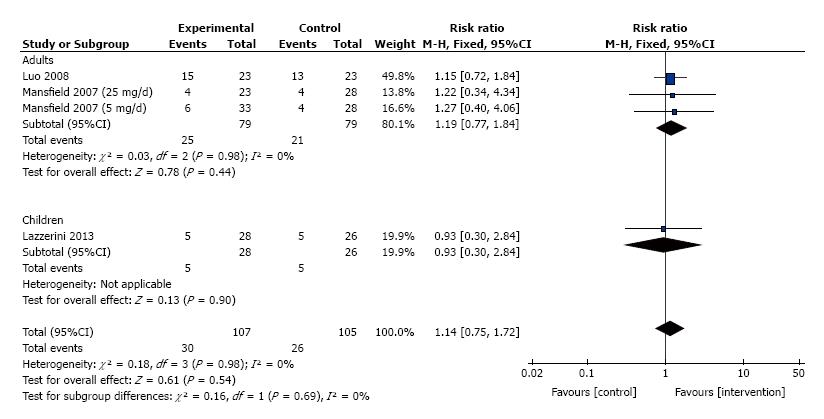

The frequency of induction of clinical response for patients treated with thalidomide was studied in 3 trials that consisted of 212 patients. No significant heterogeneity was detected between these trials (I2 = 0%, P = 0.98). We divided these trials into two subgroups, adults and children. Meta-analysis using a fixed effect model showed no difference between thalidomide and placebo for the maintenance of clinical remission (RR = 1.14, 95%CI: 0.75-1.72, P = 0.54; Figure 5).

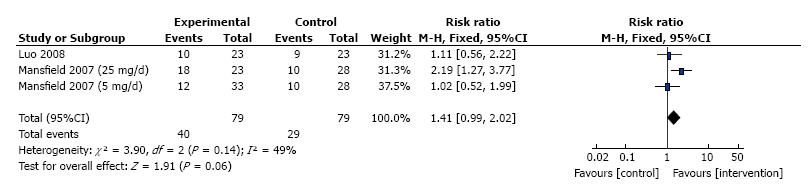

Adverse events were reported in two out of the three trials (one trial is not clear) which consisted of 69 patients, therefore the Meta analysis included only two trials. No significant heterogeneity detected between the two trials (I2 = 49%, P = 0.14), Meta- analysis using a fixed effects model showed no difference between thalidomide and placebo for the occurrence of serious side effects (RR = 1.41, 95%CI: 0.99-2.02, P = 0.06; Figure 6).

All of the outcomes were re-analyzed using a random effects model to estimate the stability of the meta-analysis. We excluded either one study at a time and analyzed the remaining studies to assess whether a particular study had an excessive influence on the results. Most of the results were consistent, as described above.

The treatment of IBD is quiet challenging in clinical practice for gastroenterologists. There is no cure for IBD; the main goals of therapy are induction and maintenance of remission. Many drugs have been used to treat IBD, but only corticosteroids are commonly used. However, corticosteroids are only effective in inducing remission, but not in maintain remission.

IBD is chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract with a long period of clinical relapse and remission[1]. A wide range of drugs have been used for the treatment of IBD, such as amino salicylic acids, thiopurines, immunomodulators such as azathioprine (AZA), mercaptopurine, methotrexate, infliximab, adalimumab. And corticosteroids. However, the effective rates of these drugs are low and they are associated with many adverse side effects[32,33]. It has now been recognized that the treatment goals should go beyond just controlling the symptoms of IBD. Rather, IBD treatments should aim to rapidly induce steroid-free remission, while minimizing serious complications and side effects[34]. The side effects that have been reported including an increased risk of infections, occurrence of autoimmune disorders[35], and risk of lymphoma or other malignancy[36].

The efficacies of thalidomide and thalidomide analogues for the treatment of IBD are of interest. Three published studies (n = 212) were included in the meta-analysis. No statistically significant difference was found between thalidomide/thalidomide analogues and placebo in terms of frequency of clinical remission and clinical response.

The main side effects that have been reported including Peripheral neuropathy, bradycardia, amenorrhea, and so on. Adverse events were reported in two out of three trials. They were not reported in one trial was not clear. We tried to contact the author by e-mail, but we were unsuccessful in retrieving the full data of these studies. Meta-analysis of the two studies did not show any statistically significant benefits from the use of thalidomide and thalidomide analogues.

Despite strict inclusion criteria have been used to reduce heterogeneity, there are still several limitations within this study. First, the degree of IBD of the patients of the trials included in this study vary considerately, ranging from mild-to-moderate to moderately severe. Second, evaluation of response was not uniform upon trial initiation, some trials enrolled patients with PCDAI ≤ 10, response: Reduction in PCDAI of ≥ 25%, while others enrolled those with CDAI < 150, reduction in CDAI by ≥ 100, and response: Reduction in CDAI by ≥ 70. Third, dosage of thalidomide and thalidomide analogues used differ between trials. All of these variability could affect the results of our analysis.

In summary, this meta-analysis has shown that there is not enough evidence to support the use of thalidomide or its analogues for the treatment of IBD for patients of any age. Many studies published so far on the use of thalidomide and thalidomide analogues for the treatment of IBD are handicapped by their small sample sizes and debatable interpretation. There were no case–control or cohort study and there were only three RCTs in publications. Therefore, it will be necessary to perform a re-analysis when more data become available.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract with a long period of clinical relapse and remission. A wide range of drugs have been used for the treatment of IBD. However, the effective rates of these drugs are low and they are associated with many adverse side effects. The increased production of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in IBD plays a major role in the pathophysiology of IBD and TNF-α tends to increase with the disease progression.

The treatment of IBD is quiet challenging in clinical practice for gastroenterologists. There is no cure for IBD, the main goals of therapy are induction and maintenance of remission. Many drugs have been used to treat IBD, but only corticosteroids are commonly used. However, corticosteroids are only effective in inducing remission, but not in maintain remission. The efficacies of thalidomide and thalidomide analogues for the treatment of IBD are of interest. Three published studies (n = 212) were included in the meta-analysis. No statistically significant difference was found between thalidomide/thalidomide analogues and placebo in terms of frequency of clinical remission and clinical response.

In this meta-analysis, the authors examined the efficacy and safety of thalidomide and thalidomide analogues for induction and maintenance of remission in 53 patients with IBD. No difference was found between thalidomide and placebo in the induction of remission (P = 0.22), clinical response (P = 0.54) and adverse events (P = 0.06). Therefore, it is concluded that there is not enough evidence to support the use of thalidomide or its analogues in the treatment of IBD patients of any age.

This meta-analysis has shown that there is not enough evidence to support the use of thalidomide or its analogues for the treatment of IBD for patients of any age. Many studies published so far on the use of thalidomide and thalidomide analogues for the treatment of IBD are handicapped by their small sample sizes and debatable interpretation.

This article, after making the meta-analysis, concluded that no enough evidence to support use of thalidomide or its analogue for the treatment in patients of any age with IBD. This article may be beneficial to the clinicians.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Lee HC S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Walsh A, Mabee J, Trivedi K. Inflammatory bowel disease. Prim Care. 2011;38:415-32; vii. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fakhoury M, Negrulj R, Mooranian A, Al-Salami H. Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and treatments. J Inflamm Res. 2014;7:113-120. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 274] [Article Influence: 27.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Frank DN, St Amand AL, Feldman RA, Boedeker EC, Harpaz N, Pace NR. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13780-13785. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3075] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3193] [Article Influence: 187.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Rawsthorne P, Wajda A. Epidemiology of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in a central Canadian province: a population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:916-924. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Burisch J, Jess T, Martinato M, Lakatos PL. The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:322-337. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 649] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 667] [Article Influence: 60.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kappelman MD, Moore KR, Allen JK, Cook SF. Recent trends in the prevalence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in a commercially insured US population. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:519-525. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 336] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ford AC, Bernstein CN, Khan KJ, Abreu MT, Marshall JK, Talley NJ, Moayyedi P. Glucocorticosteroid therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:590-599; quiz 600. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 213] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Steinhart AH, Ewe K, Griffiths AM, Modigliani R, Thomsen OO. Corticosteroids for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;CD000301. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Moffatt D, Bernstein CN. Chapter 7: State-of-the-art medical therapy of the adult patient with IBD: the immunomodulators. Inflammatory bowel disease: diagnosis and therapeutics. New York: Humana Press 2011; 93-110. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Lazzerini M, Martelossi S, Marchetti F, Scabar A, Bradaschia F, Ronfani L, Ventura A. Efficacy and safety of thalidomide in children and young adults with intractable inflammatory bowel disease: long-term results. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:419-427. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lebrin F, Srun S, Raymond K, Martin S, van den Brink S, Freitas C, Bréant C, Mathivet T, Larrivée B, Thomas JL. Thalidomide stimulates vessel maturation and reduces epistaxis in individuals with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Nat Med. 2010;16:420-428. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 246] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Coelho A, Souto MI, Cardoso CR, Salgado DR, Schmal TR, Waddington Cruz M, de Souza Papi JA. Long-term thalidomide use in refractory cutaneous lesions of lupus erythematosus: a 65 series of Brazilian patients. Lupus. 2005;14:434-439. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hyams JS, Ferry GD, Mandel FS, Gryboski JD, Kibort PM, Kirschner BS, Griffiths AM, Katz AJ, Grand RJ, Boyle JT. Development and validation of a pediatric Crohn’s disease activity index. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1991;12:439-447. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Direskeneli H, Ergun T, Yavuz S, Hamuryudan V, Eksioglu-Demiralp E. Thalidomide has both anti-inflammatory and regulatory effects in Behcet’s disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:373-375. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Woywodt A, Ludwig D, Neustock P, Kruse A, Schwarting K, Jantschek G, Kirchner H, Stange EF. Mucosal cytokine expression, cellular markers and adhesion molecules in inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:267-276. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Noguchi M, Hiwatashi N, Liu Z, Toyota T. Secretion imbalance between tumour necrosis factor and its inhibitor in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1998;43:203-209. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Bartlett JB, Dredge K, Dalgleish AG. The evolution of thalidomide and its IMiD derivatives as anticancer agents. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:314-322. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 598] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 575] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Vallet S, Palumbo A, Raje N, Boccadoro M, Anderson KC. Thalidomide and lenalidomide: Mechanism-based potential drug combinations. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:1238-1245. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 79] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | D’Amato RJ, Lentzsch S, Anderson KC, Rogers MS. Mechanism of action of thalidomide and 3-aminothalidomide in multiple myeloma. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:597-601. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Schafer P. Apremilast mechanism of action and application to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:1583-1590. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 270] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Srinivasan R, Akobeng AK. Thalidomide and thalidomide analogues for induction of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;CD007350. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Akobeng AK, Stokkers PC. Thalidomide and thalidomide analogues for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;CD007351. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Franks ME, Macpherson GR, Figg WD. Thalidomide. Lancet. 2004;363:1802-1811. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bessmertny O, Pham T. Thalidomide use in pediatric patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:521-525. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sampaio EP, Sarno EN, Galilly R, Cohn ZA, Kaplan G. Thalidomide selectively inhibits tumor necrosis factor alpha production by stimulated human monocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;173:699-703. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Rowland TL, McHugh SM, Deighton J, Ewan PW, Dearman RJ, Kimber I. Selective down-regulation of T cell- and non-T cell-derived tumour necrosis factor alpha by thalidomide: comparisons with dexamethasone. Immunol Lett. 1999;68:325-332. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: Version 5.1[updated March 2011]. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2009. Accessed May 10 2014; Available from: http: // handbook.cochrane.org.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1-12. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Lazzerini M, Martelossi S, Magazzù G, Pellegrino S, Lucanto MC, Barabino A, Calvi A, Arrigo S, Lionetti P, Lorusso M. Effect of thalidomide on clinical remission in children and adolescents with refractory Crohn disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2164-2173. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 79] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Luo ZR, Si JM. Observation on the Effect of Thalidomide for the Treatment of Crohn’s Disease. Yixue Linchuang Yanjiu. 2008;25:647-648. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Mansfield JC, Parkes M, Hawthorne AB, Forbes A, Probert CS, Perowne RC, Cooper A, Zeldis JB, Manning DC, Hawkey CJ. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of lenalidomide in the treatment of moderately severe active Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:421-430. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Reinisch W, Van Assche G, Befrits R, Connell W, D’Haens G, Ghosh S, Michetti P, Ochsenkühn T, Panaccione R, Schreiber S. Recommendations for the treatment of ulcerative colitis with infliximab: a gastroenterology expert group consensus. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:248-258. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Lee KM, Jeen YT, Cho JY, Lee CK, Koo JS, Park DI, Im JP, Park SJ, Kim YS, Kim TO. Efficacy, safety, and predictors of response to infliximab therapy for ulcerative colitis: a Korean multicenter retrospective study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:1829-1833. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Panaccione R, Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan B, Schreiber S, Ghosh S. Review article: treatment algorithms to maximize remission and minimize corticosteroid dependence in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:674-688. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Sandborn WJ, van Assche G, Reinisch W, Colombel JF, D’Haens G, Wolf DC, Kron M, Tighe MB, Lazar A, Thakkar RB. Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:257-65.e1-3. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 817] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 858] [Article Influence: 71.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J, Lu J, Horgan K, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB. Colectomy rate comparison after treatment of ulcerative colitis with placebo or infliximab. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1250-1260; quiz 1520. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 360] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |