Published online Sep 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i18.4272

Peer-review started: April 13, 2020

First decision: July 25, 2020

Revised: August 4, 2020

Accepted: August 20, 2020

Article in press: August 20, 2020

Published online: September 26, 2020

Lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma (LPRM) is one of the rarest variants of meningioma and is classified as grade I (benign) tumor. It is characterized by abundant infiltrates of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Here, we report an extremely rare case of LPRM with an atypical imaging finding of multiple cysts around a solid mass.

The patient was a 36-year-old man with intermittent headache, dizziness, and vomiting for 2 years. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging presented a cystic solid mass in the right frontal lobe with heavy peritumoral edema and obvious contrast enhancement. The patient was treated with right frontotemporal craniotomy, and gross total resection of the tumor was achieved without adjuvant therapy. There was no clinical or neuroradiological evidence of recurrent or residual tumor for 3 years after initial surgery.

LPRM is one of the rarest variants of meningioma. Although, the mass of this case had common features, multiple cysts with nonuniform size and thin wall around the solid part are uncommon imaging finding, increasing the rate of misdiagnosis. The definitive diagnosis of LPRM relies on histopathological findings.

Core Tip: Lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma (LPRM) is one of the rarest variants of meningioma. A case of LPRM is presented here with atypical imaging finding of multiple cysts around a solid mass, which has been reported even more rarely. In computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings, the mass had common features: An irregular shape, unclear boundary with neighboring brain tissue, heavy peritumoral brain edema, significant enhancement of the solid part, and dural tail sign. Multiple cysts with nonuniform size and thin wall around the solid part are uncommon imaging finding, increasing the rate of misdiagnosis. The definitive diagnosis of LPRM relies on histopathological findings.

- Citation: Gu KC, Wan Y, Xiang L, Wang LS, Yao WJ. Lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma with atypical cystic-solid feature: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(18): 4272-4279

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i18/4272.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i18.4272

Lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma (LPRM) is one of the rarest variants of meningioma and is classified as grade I (benign) tumor, which has a low proliferative rate[1,2]. LPRM is characterized by abundant infiltrates of inflammatory cells, such as lymphocytes and plasma cells. The first case was reported in 1971 by Banerjee and Blackwood[3], and < 120 cases have been reported in the English language literature. Available data on the incidence of LPRM is scarce and incomplete.

Here, we report a case of LPRM with atypical imaging finding of multiple cysts around a solid mass, which has been reported even more rarely.

A 36-year-old man presented to the Neurosurgery Department of our hospital complaining of worsening headache, accompanied by fainting and numbness in his right upper extremities.

The patient’s symptoms started 2 years prior with intermittent headache, dizziness, and vomiting, without any obvious predisposing causes.

The patient had a free previous medical history.

The clinical neurological examination revealed right upper extremities hypoesthesia and numbness. There were no seizures or disorder of consciousness.

The blood analysis, blood biochemistries, as well as urine analysis were normal. Electrocardiogram, chest X-ray, and arterial blood gas were also normal. Prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times were normal.

Non-contrast computed tomography (CT) and contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were performed before surgery.

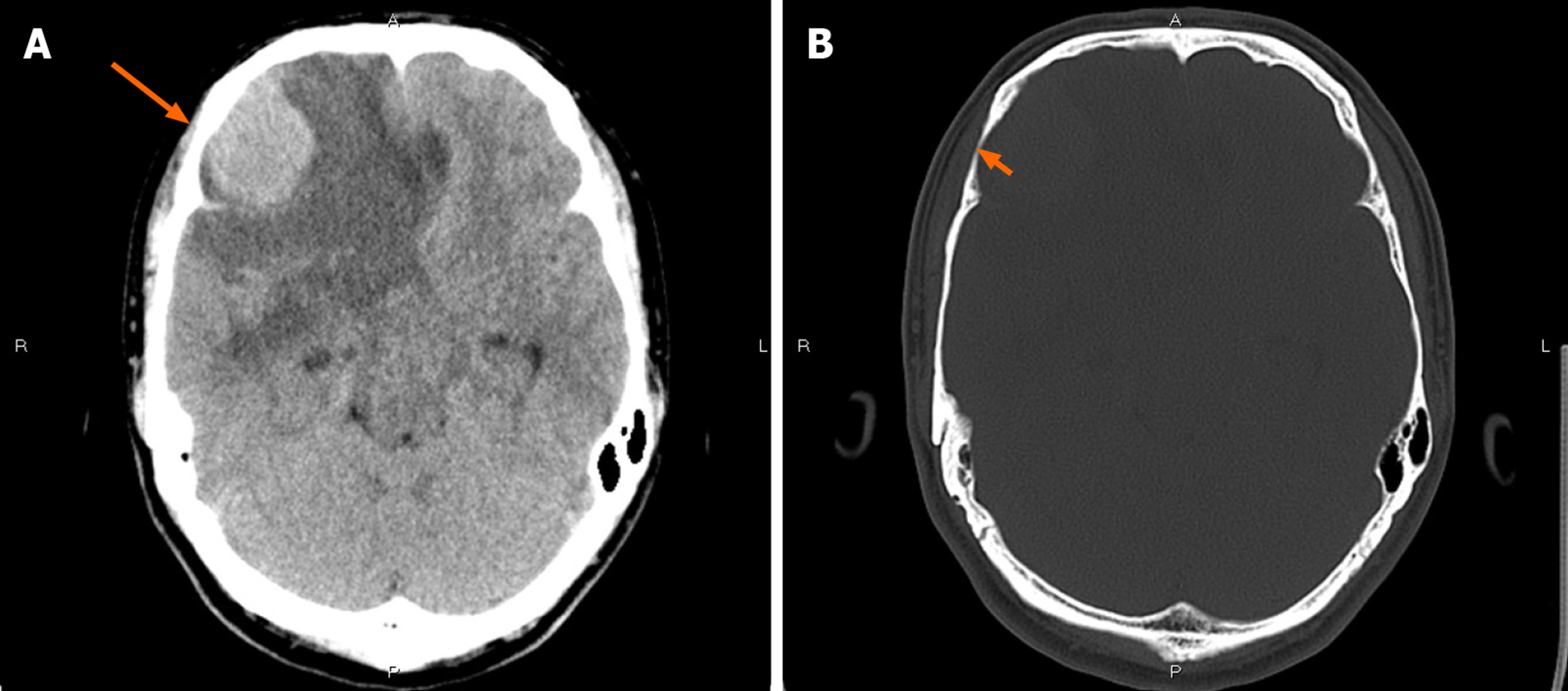

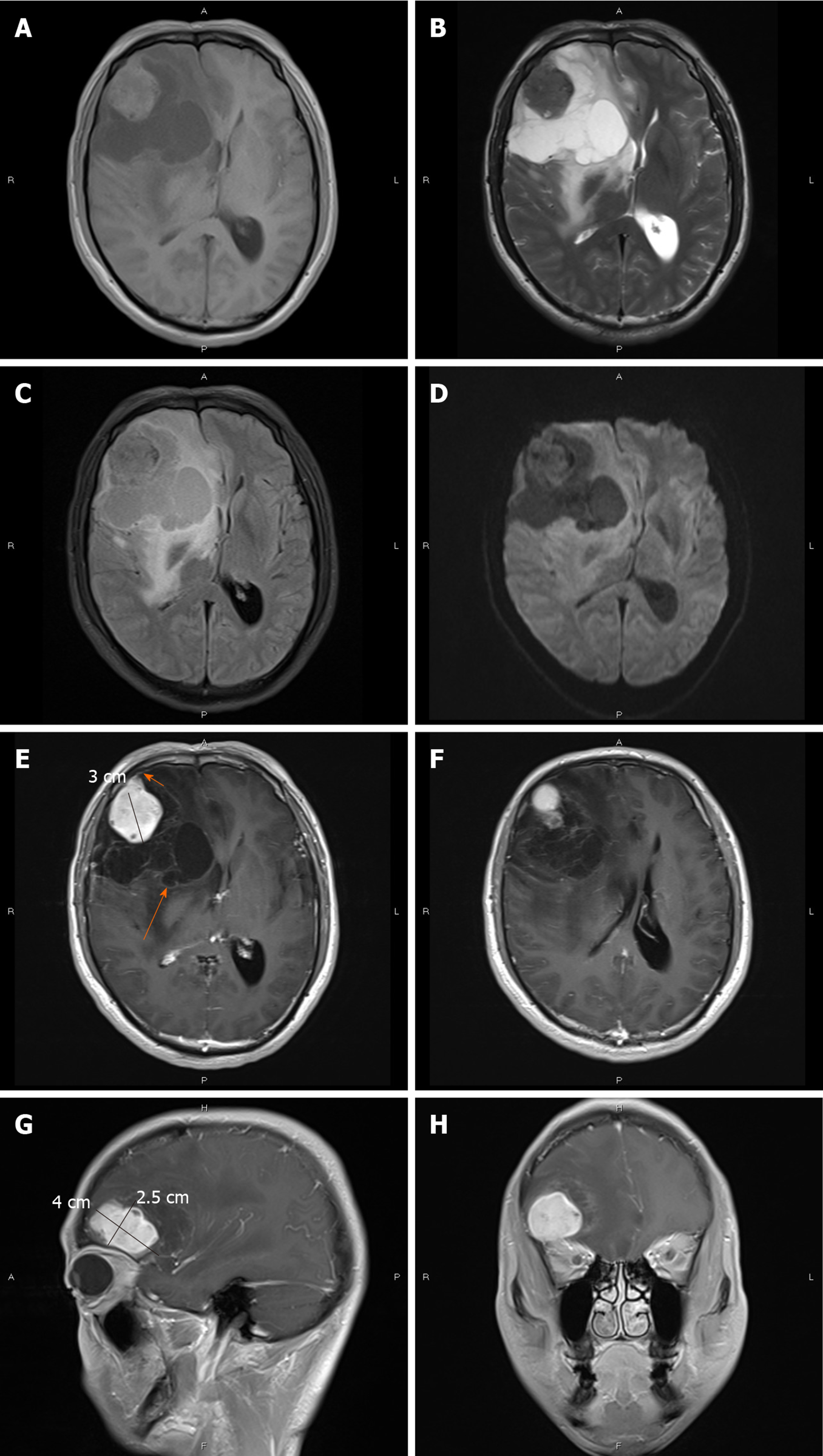

CT showed an irregular hypodense and isodense mixed mass in the right frontal lobe, which had caused obvious peritumoral edema (Figure 1A). The right frontal bone became thin (Figure 1B). Subsequent brain MRI revealed a large cystic solid mass in the right frontal lobe (Figure 2). The solid part of the mass measured approximately 4 cm × 3 cm × 2.5 cm. Compared with gray matter, the solid part of the mass was slightly heterogeneous and hyperintense on T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) and slightly hypointense on T2-weighted imaging (T2WI). It showed isointensity on fluid attenuated inversion recovery and diffusion-weighted imaging. Several spots of hypointensity on T1WI and hyperintensity on T2WI in the solid part of the lesion were also found. Multiple cysts with nonuniform size comprised the cystic part, which showed hypointensity on T1WI and hyperintensity on T2WI. The signal was little higher than cerebrospinal fluid on T2WI. The cystic walls were thin. The solid part and cystic wall were strongly enhanced after gadolinium-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid administration. The whole mass had an unclear boundary with adjacent brain issue, and heavy peritumoral edema. The dural tail sign was observed. The anterior horn of the right lateral ventricle was compressed, and the brain midline was shifted to the left.

Due to the aforementioned imaging findings, differential diagnosis mainly included meningioma (World Health Organization [WHO] grade II or higher), while the possibility of metastatic tumor and primary solitary intracranial malignant melanoma could not entirely be excluded.

With regard to this case, radiologic findings were more fit for meningioma due to the present of dural tail and significant enhancement. But the presence of heavy peritumoral edema and unclear boundary make it tend to be more aggressive and higher grade, which are different from typical imaging characteristics of benign meningioma. So, the diagnosis of meningioma (WHO grade II or higher) was suspected. Meanwhile, the possibility of metastatic tumor and primary solitary intracranial malignant melanoma could not entirely be excluded. However, the peritumoral multiple cystic with nonuniform size and thin wall does not tend to be necrosis, which does not fit the aforementioned tumors. The preoperative diagnosis is challenging.

The patient underwent right frontotemporal craniotomy to resect the lump. Intraoperative observation showed that the tumor was located on the surface of the right frontal lobe and involved the anterior cranial fossa. The mass was cystic solid. The solid part of the mass was flesh pink, with tough texture and moderate blood supply. The diameter of the solid part was approximately 3.5 cm. There were multiple cysts behind the solid part, and they were filled with yellowish fluid. The lump invaded the dura mater and grew towards the skull. Gross total resection was achieved.

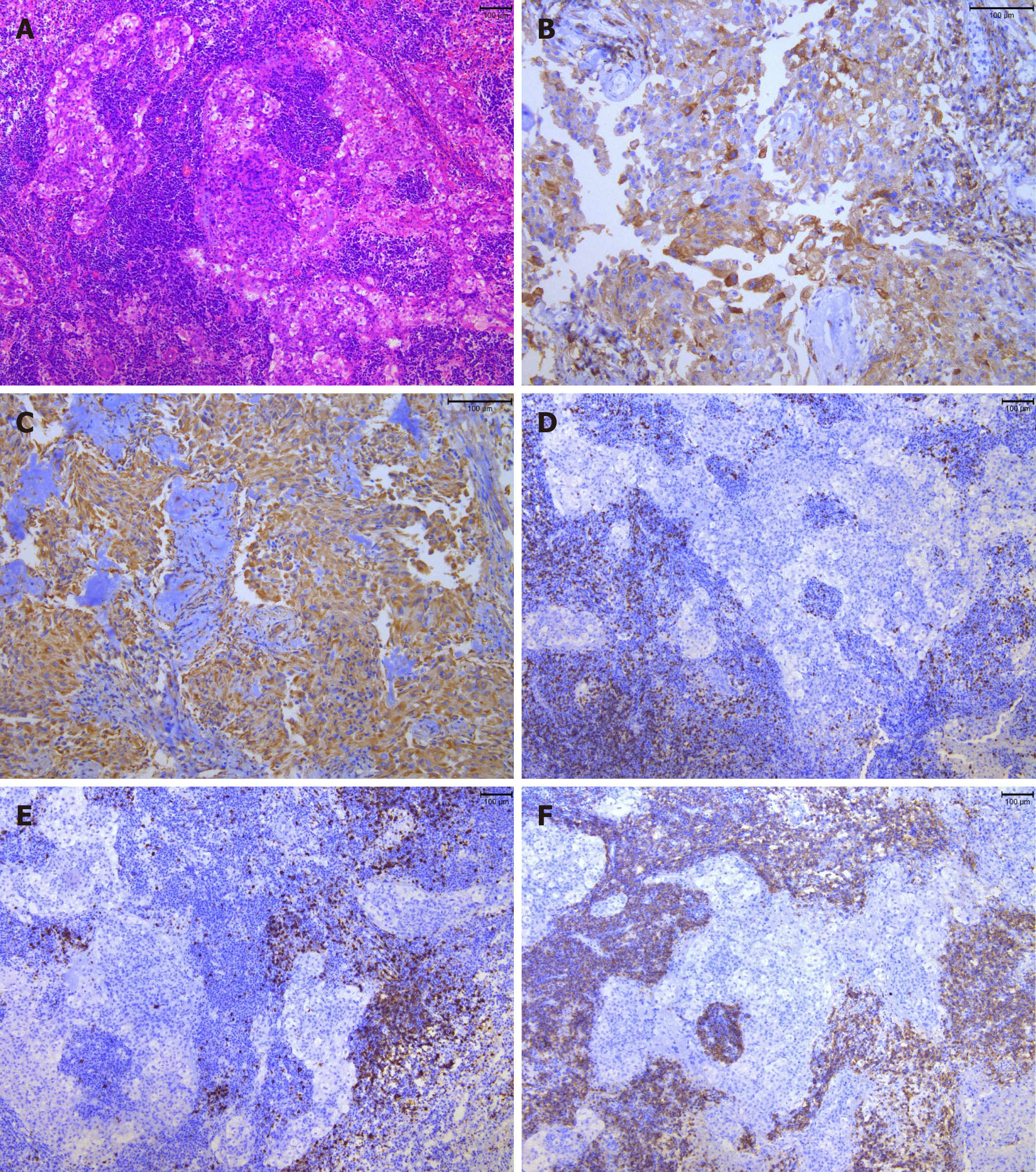

After resection, the tumor was observed by hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E) and immunohistochemical examination (including epithelial membrane antigen [EMA], vimentin, leukocyte common antigen [LCA], cluster of differentiation 3 [CD3], CD20, CD138, CD38, S-100, glial fibrillary acidic protein, PR and Ki-67). Histopathological examination revealed a gray–white and taupe appearance with tough tissue on the sections of the gross specimen (Figure 3A-F). H&E staining showed that there were multiple nests of meningothelial cells and syncytial tumor cells arranged in sheets or weaving. The nuclei of the tumor cells appeared uniform in size with obvious atypia. Tumor stroma was infiltrated with large numbers of lymphocytes and plasmocytes, and local focus of lymphoid follicular formation. Immunohistochemical examination showed that the tumor cells were positive for EMA, vimentin, LCA, CD3, CD20, CD138 and CD38, and negative for S-100, glial fibrillary acidic protein and PR. The average proportion of Ki-67 positive cells was < 5%.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was LPRM.

The patient underwent right frontotemporal craniotomy to resect the lump. Gross total resection was achieved. Adjuvant radiation therapy was not administered after surgery.

There was no clinical or radiological evidence of recurrent or residual tumor at 3 years after initial surgery.

Meningioma is one of the most common intracranial tumors, accounting for 26%-35% of all primary intracranial tumors. The WHO classification (2016) divides meningioma into 16 types and three grades[1]. LPRM is an extremely rare variant that is characterized histopathologically by proliferation of meningeal epithelial cells and massive infiltration of inflammatory cells, such as lymphocytes and plasmocytes. Despite its WHO classification as a benign tumor, the infiltration of adjacent brain tissue is frequently seen by MRI[2].

This type of meningioma was first reported by Banerjee and Blackwood in 1971[3], and it has been classified as grade I by WHO since 1993[4,5]. To date, only about 120 cases have been reported. Available data on the incidence of LPRM are scarce and incomplete. The largest series of cases reported by Tao et al[6] showed that the incidence was 0.51%. It usually occurs in young and middle-aged patients without sex predominance, which is different from other common types of meningiomas. Symptoms of intracranial hypertension occur early. Previous reports indicate that the most frequent locations of LPRM is the convexity and cerebellopontine angle[7,8], rarely involving the whole intracranial dura mater[9] and intraosseous extradural site[10]. Our case occurred in the right frontal lobe, the most common site of LPRM, consistent with previous reports.

Clinically, LPRM is often accompanied by diseases of the hematopoietic system, including anemia or polyclonal gammopathy, which can be resolved after tumor removal[8,11]. The clinical features of our patient included headache, dizziness and vomiting, which were similar to those reported previously[11], but there was no evidence of systemic hematological abnormalities.

There is still some debate about whether LPRM is a true neoplasm, as its behavior is often similar to an inflammatory condition. Under microscopy, our case showed typical histological features of LPRM according to the WHO classification. H and E stain showed that the tumor consisted of multiple nests of meningothelial cells and syncytial cells. Sings of nuclear fission were rare. The tumor stroma was infiltrated with large numbers of lymphocytes and plasmocytes.

Immunohistochemical staining showed that EMA and vimentin were positive, which means that the tumor originated from the arachnoid cap cells[12]. LCA, CD3 and CD20 were positive, which indicate that the tumor had an abundance of T and B lymphocytes. A large number of plasmocytes could be seen with CD138 and CD38 staining, which was similar to that reported in the literature[12,13]. Ki-67 identified the proliferative index of the meningioma component. In our case, it was < 5%, which means the proliferative index of the tumor was low[14].

The tumor had the following features, consistent with previous studies[2,6,8,15]: An irregular shape, unclear boundary with neighboring brain tissue, heavy peritumoral brain edema, and dural tail sign. Of note, the dural tail is not pathognomonic for meningioma and may also be seen in metastases or hemangiopericytomas, but is frequently useful in distinguishing meningioma from other lesions where it is absent[16]. It is known that tumors tend to be malignant[17] if they have an irregular shape, obvious edema, and infiltration of adjacent brain tissue[18]. However, LPRM is a benign tumor but has the above imaging characteristics. Unlike typical benign meningioma[16,19], the unclear boundary and irregular shape may be related to the presence of inflammatory cells. Although less common, peritumoral edema on T2 and T2-fluid attenuated inversion recovery imaging may also be seen, particularly in secretory meningioma subtype and in more aggressive meningiomas that invade the brain[16]. Current studies suggest that peritumoral edema is associated with many factors, such as tumor blood supply, position, as well as lymphoplasmacytic infiltration[20,21]. Microscopic observation in this case indicated that there were many lymphocytes and plasmocytes, and the signs of nuclear atypia were not obvious. So, infiltration of inflammatory cells was considered to be the main cause of heavy peritumoral edema in LPRM[15].

CT and MRI both showed that the mass was divided into solid and multiple cystic components, which was consistent with intraoperative observation. Plain CT imaging showed that the solid part had higher density. Meanwhile, pathological findings revealed that tumor cells were dense and abundant, with less tumor stroma, and contained a large number of lymphoplasmacytes. So, we think that the solid part of the mass had higher density because it contained more tumor cells and less stroma. The typical signals of LPRM on MRI are mainly lower-isointense on T1WI and hyperintense on T2WI. In the present case, it showed slightly heterogeneous hyperintensity on T1WI and slight hypointensity on T2WI, which have been described previously[6]. Hyperintense signals on T1WI and hypointense signals on T2WI in the brain are often found in intracranial melanoma[22]. Therefore, it is often misdiagnosed as malignant tumors, such as cystic brain metastases[23] and primary solitary intracranial malignant melanoma. Metastatic tumor most often emerge in older people, a history of malignancy in other sites of the body, heavy peritumoral edema, and often occurs in the junction of the cortex and medulla. However, in addition to the above manifestations, cystic brain metastases also have the characteristics of necrosis in the center of the tumor. Primary solitary intracranial malignant melanoma usually presents high-density on the precontrast CT, hyperintensity on T1-weighted images and hypointensity on T2-weighted images[22], which is similar to the solid part of our case.

Thus far, there have been only five cases with peri- or intratumoral cystic changes, and most had intratumoral cystic necrosis[2,8,24]. Katayama et al[24] first reported LPRM that showed ring enhancement and a mural nodule, whose cystic change also tended toward cystic necrosis. In our patient, the multiple cystic change was peritumoral, which made preoperative diagnosis more difficult.

Additionally, the solid part of the tumor showed strong heterogeneous enhancement, which has been reported previously[2,6,8,15]. A previous study indicated that many lymphocytes and plasmocytes may form a cuff-like structure around the vascular tissue and damage the blood–brain barrier, which leads to peritumoral edema and obvious enhancement on MRI[2].

We have reported a case of LPRM with atypical cystic solid features in a 36-year-old man who presented with occasional headache, dizziness, and vomiting. In CT and MRI findings, the mass had the following common features: An irregular shape, unclear boundary with neighboring brain tissue, heavy peritumoral brain edema, significant enhancement of the solid part, and dural tail sign. Multiple cysts with nonuniform size and thin wall around the solid part are uncommon imaging findings, increasing the rate of misdiagnosis. The definitive diagnosis of LPRM relies on histopathological findings.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Anhui Radiology Branch of Chinese Medical Association, No. 0419.

Specialty type: Radiology, nuclear medicine and medical imaging

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Aygun C, Mohamed SY, Vynios D S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Kleihues P, Ellison DW. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803-820. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10993] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9857] [Article Influence: 1232.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Liu JL, Zhou JL, Ma YH, Dong C. An analysis of the magnetic resonance imaging and pathology of intracal lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:968-973. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Banerjee AK, Blackwood W. A subfrontal tumour with the features of plasmocytoma and meningioma. Acta Neuropathol. 1971;18:84-88. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wiestler OD, Wolf HK. [Revised WHO classification and new developments in diagnosis of central nervous system tumors]. Pathologe. 1995;16:245-255. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, Scheithauer BW, Kleihues P. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97-109. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7079] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7747] [Article Influence: 455.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tao X, Wang K, Dong J, Hou Z, Wu Z, Zhang J, Liu B. Clinical, Radiologic, and Pathologic Features of 56 Cases of Intracranial Lymphoplasmacyte-Rich Meningioma. World Neurosurg. 2017;106:152-164. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wang YB, Wang WJ, Xu SB, Xu BF, Yu Y, Ma H, Zhang XF. Intraventricular lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma: a case report. Turk Neurosurg. 2014;24:958-962. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhu HD, Xie Q, Gong Y, Mao Y, Zhong P, Hang FP, Chen H, Zheng MZ, Tang HL, Wang DJ, Chen XC, Zhou LF. Lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma: our experience with 19 cases and a systematic literature review. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2013;6:504-515. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Yang X, Le J, Hu X, Zhang Y, Liu J. Lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma involving the whole intracranial dura mater. Neurology. 2018;90:934-935. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang Y, Teng Y, Xu H, Li Y. Primary Intraosseous Lymphoplasmacyte-Rich Meningioma. World Neurosurg. 2018;109:291-293. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nakayama Y, Watanabe M, Suzuki K, Usuda H, Emura I, Toyoshima Y, Takahashi H, Kawaguchi T, Kakita A. Lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma: a convexity mass with regional enhancement in the adjacent brain parenchyma. Neuropathology. 2012;32:174-179. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Avninder S, Gupta V, Sharma KC. Lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma at the foramen magnum. Br J Neurosurg. 2008;22:702-704. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yoneyama T, Kasuya H, Kubo O, Hori T. [Lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma: a report of three cases and a review of the literature]. No Shinkei Geka. 1999;27:383-389. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Mawrin C. [Molecular biology, diagnosis, and therapy of meningiomas]. Pathologe. 2019;40:514-518. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yongjun L, Xin L, Qiu S, Jun-Lin Z. Imaging findings and clinical features of intracal lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma. J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26:e132-e137. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Buerki RA, Horbinski CM, Kruser T, Horowitz PM, James CD, Lukas RV. An overview of meningiomas. Future Oncol. 2018;14:2161-2177. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 242] [Article Influence: 40.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Champeaux C, Jecko V, Houston D, Thorne L, Dunn L, Fersht N, Khan AA, Resche-Rigon M. Malignant Meningioma: An International Multicentre Retrospective Study. Neurosurgery. 2019;85:E461-E469. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nohara H, Furuya K, Kawahara N, Iijima A, Yako K, Shibahara J, Kirino T. Lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma with atypical invasive nature. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2007;47:32-35. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Nowosielski M, Galldiks N, Iglseder S, Kickingereder P, von Deimling A, Bendszus M, Wick W, Sahm F. Diagnostic challenges in meningioma. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19:1588-1598. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 79] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lee KJ, Joo WI, Rha HK, Park HK, Chough JK, Hong YK, Park CK. Peritumoral brain edema in meningiomas: correlations between magnetic resonance imaging, angiography, and pathology. Surg Neurol. 2008;69:350-5; discussion 355. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 65] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Loh JK, Hwang SL, Tsai KB, Kwan AL, Howng SL. Sphenoid ridge lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma. J Formos Med Assoc. 2006;105:594-598. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Arai N, Kagami H, Mine Y, Ishii T, Inaba M. Primary Solitary Intracranial Malignant Melanoma: A Systematic Review of Literature. World Neurosurg. 2018;117:386-393. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Brigell RH, Cagney DN, Martin AM, Besse LA, Catalano PJ, Lee EQ, Wen PY, Brown PD, Phillips JG, Pashtan IM, Tanguturi SK, Haas-Kogan DA, Alexander BM, Aizer AA. Local control after brain-directed radiation in patients with cystic versus solid brain metastases. J Neurooncol. 2019;142:355-363. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Katayama S, Fukuhara T, Wani T, Namba S, Yamadori I. Cystic lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1997;37:275-278. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |