Published online Nov 16, 2016. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v4.i11.369

Peer-review started: June 29, 2016

First decision: August 5, 2016

Revised: August 6, 2016

Accepted: August 27, 2016

Article in press: August 29, 2016

Published online: November 16, 2016

Processing time: 139 Days and 5.4 Hours

Severe alcoholic hepatitis (AH) has a high mortality, and it is associated with encephalopathy, acute renal failure, sepsis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and endotoxemia. The 28-d mortality remains poor (34%-40%), because no effective treatment has been established. Recently, corticosteroids (CS) have been considered effective for significantly improving the prognosis of those with AH, as it prevents the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. However, CS are not always appropriate as an initial therapeutic option, such as in cases with an infection or resistance to CS. We describe a patient with severe AH complicated by a severe infection caused by the multidrug resistance bacteria (Pseudomonas aeruginosa), and was successfully treated with granulocytapheresis monotherapy without using CS. The experience of this case will provide understanding of the disease and information treating cases without using CS.

Core tip: Severe alcoholic hepatitis (AH) has a high mortality, and it is associated with encephalopathy, acute renal failure, sepsis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and endotoxemia. Corticosteroids (CS) have shown efficacy in patients with AH by inhibiting the production of cytokines. On the other hand, the use of a CS is not always appropriate during the initial stage when the patient is complicated with the infection, gastrointestinal bleeding, etc. which can be progressed by CS. For these cases, granulocytapheresis (GCAP) is expected to significantly improve the prognosis of those with severe AH, as the granulocyte and monocyte apheresis device inhibits liver injury caused by activated neutrophils. We presented here the case successfully treated with GCAP without using CS because of severe infectious status.

- Citation: Watanabe Y, Kamimura K, Iwasaki T, Abe H, Takahashi S, Mizuno KI, Takeuchi M, Eino A, Narita I, Terai S. Case of severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with granulocytapheresis. World J Clin Cases 2016; 4(11): 369-374

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v4/i11/369.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v4.i11.369

Severe alcoholic hepatitis (AH) has a considerably high mortality, and it is associated with encephalopathy, renal failure, sepsis, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, and endotoxemia[1]. In cases with a Maddrey discriminant function (MDF) score ≥ 32, the 28-d mortality is about 34%-40%[2-7], and in cases with a Glasgow alcoholic hepatitis score (GAHS) ≥ 9, the 28-d mortality is about 60%[5]. The following factors of a poor prognosis have been reported: age; the presence of encephalopathy; an increase in the white blood cell (WBC) count, prothrombin time (PT), and serum bilirubin level; and renal failure[7-9]. Particularly, an abnormal increase in the WBC count occurred in most deaths due to severe AH[10].

Many randomized control trials (RCTs)[3,4,11] and reviews[12] have reported the efficacy of using corticosteroids (CS) to treat AH; however, no reports have shown that CS also improve long-term outcomes, e.g., at 3 mo and 1 year[7,11,12]. Additionally, the use of a CS is associated with a risk of complications, including gastrointestinal bleeding and infection[7]. Therefore, the establishment of additional therapeutic strategies is essential and the efficiency of granulocytapheresis (GCAP) has been reported as a novel treatment option[6,10,13-15] to date, especially from Japan. Since GCAP is standard treatment for inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD)[16] and has shown the promising therapeutic effect in the patients with CS resistant type of IBDs by reducing the number of WBC and activity of the diseases, it was thought that it may be effective for preventing the progression of severe AH.

To date, 38 cases have been treated (see recent ref.[14]) with leukocytapheresis (LCAP), and the outcome was favorable, with a survival rate of 60.5% (23/38)[14,17,18]. Most cases were treated with multimodality therapy, including a CS (25/38), but the use of a CS is associated with the risk of exacerbating the condition with severe infections.

We describe a patient with severe AH complicated by sepsis who was treated early with GCAP without a CS followed by a literature review.

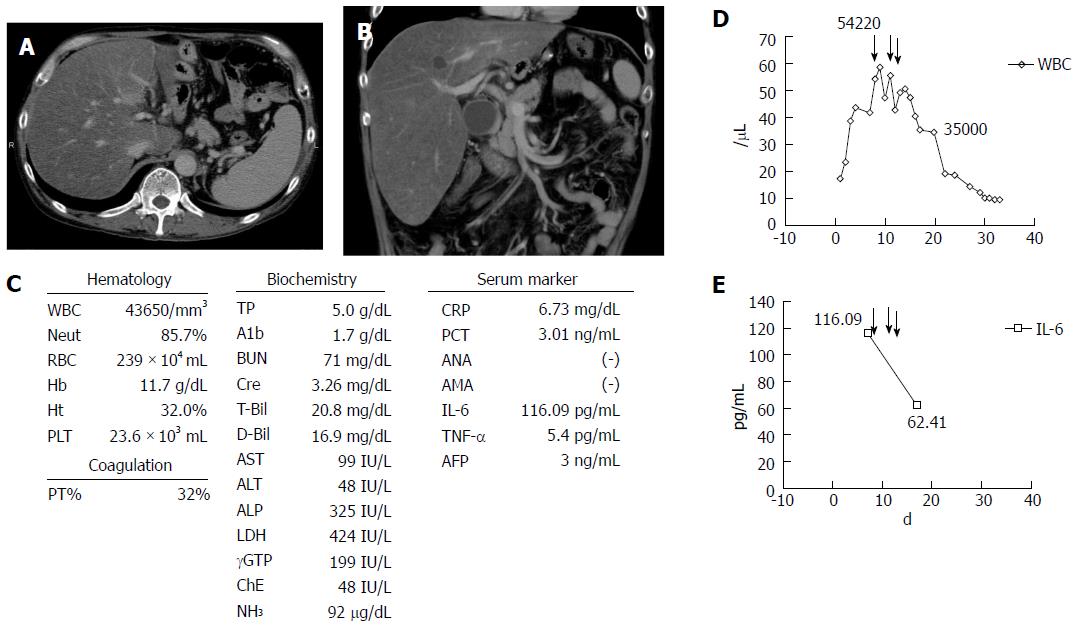

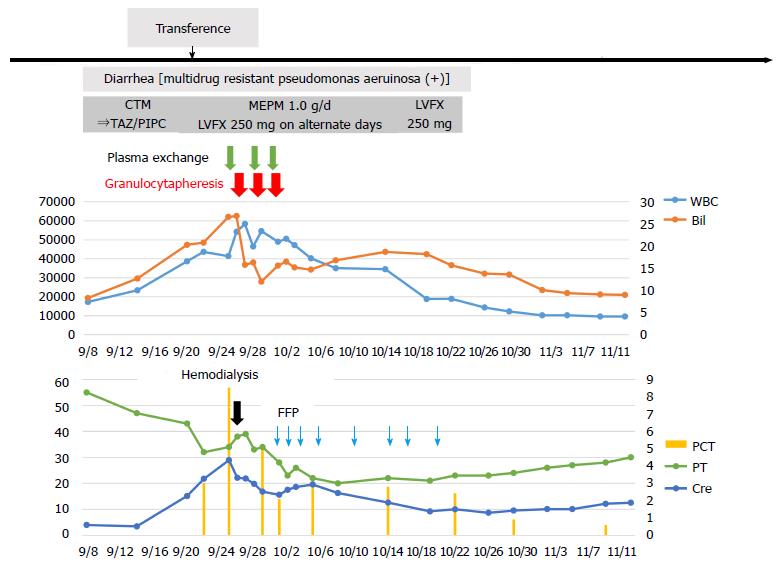

A 50-year-old Japanese man presented at a local hospital with a fever, loss of appetite, and watery diarrhea (more than 10 times per day) in August 2015. He had been a heavy drinker for about 10 years, and he consumed approximately 250 g of alcohol per day in the previous 6 mo. On admission, laboratory data showed a significant increase in the WBC count [WBC, 17280/μL (neutrophils 82.4%)], C-reactive protein level (CRP, 3.97 mg/dL), total bilirubin level (T.bil, 8.0 mg/dL), and PT (55%). Enhanced computed tomography (CT) image showed marked hepatomegaly with severe steatosis, splenomegaly, and a diffuse, edematous colon (Figure 1A and B). He was diagnosed as having acute AH with infectious enteritis. He was instructed to abstain from alcohol, and we prescribed antibiotics. However, the WBC count and T.bil level continued to increase to 43650/μL (neutrophils 85.7%) and 20.8 mg/dL, respectively, and the PT decreased to 34%. In addition, renal failure progressed markedly, resulting in hyporesis, and the creatinine level increased to 3.26 mg/dL (Figure 1C). His condition was deteriorating, thus he was transferred to our hospital for multidisciplinary treatment on the 14th day from disease onset.

On admission to our hospital, he had a fever, jaundice, anuria, ascites, pretibial edema, marked hepatomegaly, and hepatic encephalopathy with a flapping tremor. Laboratory data showed significantly increased levels of the following parameters: WBC, 54000/μL (neutrophils 85.7%); T-bil, 26.8 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase, 99 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase, 48 IU/L; NH3, 92 μg/dL; albumin, 4 g/dL; blood urea nitrogen, 71 mg/dL; creatinine, 3.26 mg/dL; CRP, 6.73 mg/dL; procalcitonin (PCT), 8.53 ng/mL, and PT, 32%. Additionally, the plasma levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-6 (116.09 pg/mL) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (5.4 pg/mL) were significantly increased (Figure 1C, D and E). On the basis of the aforementioned findings, a diagnosis of severe AH with multiple organ failure and severe infectious enteritis was made according to the Diagnostic Criteria for Alcoholic Liver Disease established by Takada et al[1]. The MDF score was 66 (≥ 32), and the GAHS was 11 (≥ 9). Results of the fecal culture showed an infection with multidrug resistance bacteria (Pseudomonas aeruginosa), which was likely the cause of severe diarrhea. Therefore, considering the severe infection and renal failure, the grade of AH was severe, and the prognosis seemed poor. No other markers of viral hepatitis and autoimmune hepatitis were observed.

He received intensive care, including plasma exchange (PEX), hemodialysis (HD), the administration of antibiotics, etc.; however, there was no improvement of liver failure, and a high WBC count was seen (Figure 2). Therefore, we performed GCAP using an Adacolumn device (JIMRO, Takasaki, Japan) on the 14th day of hospitalization. A significant decrease in the WBC count was observed (from 54220/μL to 46450/μL) after the first session, and the T.bil level improved from 26.8 mg/dL to 15.8 mg/dL. Therefore, GCAP was performed three times within 1 wk. The WBC count further improved to 35000/μL within 1 wk after the first GCAP treatment (Figure 2). Additionally, the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α improved significantly after the GCAP treatments (Figure 1D and E). After antibiotics were administered (meropenem, 1.0 g/d and levofloxacin, 250 mg every second day) (Figure 2), the patient’s diarrhea, fever, and laboratory parameters improved, and the disappearance of P. aeruginosa was confirmed by a culture. Renal failure also gradually improved, and he was transferred from our hospital to the previous hospital for rehabilitation on the 70th hospital day. No steroids were administered during his clinical course.

AH is a clinical syndrome characterized by a fever, jaundice, and liver failure after chronic alcohol consumption[2,6]. Furthermore, a significant increase in the WBC count and serum levels of endotoxin and pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α) is common in cases of severe AH. Abstinence from alcohol, nutrition therapy, etc., are initial treatments for severe AH. However, severe AH still has a high mortality, because no effective treatment has been established, although a large number of RCTs and studies have been reported on this disease.

An MDF score > 32 and/or encephalopathy indicates a very poor prognosis, and the reported 28-d mortality rate ranges from 34%-40%[2,4-6,11]. The complications of acute renal failure and sepsis are significant poor prognostic factors[8]. In our case, the patient presented with a significantly increased WBC count, jaundice, marked hepatomegaly, and ascites, and liver failure progressed to acute renal failure and infectious enteritis. Considering his MDF score, we predicted that his prognosis would be very poor.

The principal factor for the mechanism of AH is the abnormal activation of intrahepatic Kupffer cells by lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-endotoxemia. The levels of LPS, a component of gram-negative bacteria, increase in the portal and/or systemic circulation in several types of chronic liver diseases. Increased gut permeability and LPS play a role in alcoholic liver disease, as alcohol impairs the gut’s epithelial integrity by altering tight junction proteins[19]. Increased LPS activates the toll–like receptor 4 of Kupffer cells, which causes the cascade of pro-inflammatory cytokines and intrahepatic microvasculature. Activated vascular endothelial cells by pro-inflammatory cytokines are expressed as adhesion molecules, and neutrophils infiltrate the liver parenchyma. Some authors have reported that significantly increased circulating myeloid leucocytes were seen in patients with severe AH, both in the peripheral circulation and liver microvasculature[15,20]. Eventually, activated neutrophils impair liver function by some mechanism, e.g., by producing elastase, proteases, and reactive oxygen metabolites[15,21]. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that severe AH can be treated by blocking the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and activated neutrophils.

To date, CS are most commonly used for inhibiting the production of cytokines. The latest RCTs have shown that CS decreased the 28-d mortality rate; however, the levels of evidence vary. The efficacy of CS remains controversial, because the authors of a meta-analysis questioned the existing evidence, as there may be a high risk of bias[4,22]. It was reported that about 40% of patients were non-responders to CS treatment[23]; thus, CS are not always effective in every case of severe AH. Moreover, CS are associated with the risk of causing more severe complications in cases with infection, virus hepatitis, and GI bleeding[2,6], as serious infections have been reported to significantly occur more in patients treated with a CS than in those treated with a placebo[7].

PTX is also considered to be used in AH cases since it is a therapeutic agent that inhibits the production of TNF-α; however, the latest multi-center RCT[7] and review[12,24] found that PTX alone does not significantly improve patients’ prognosis. N-acetylcysteine showed a similar effect, but it may be effective when combined with a CS[12].

However, GCAP/LCAP is a novel treatment option for directly removing activated neutrophils, which cause liver injury, and many studies have reported its effectiveness[13,14,16-18,25-34]. GCAP/LCAP is the standard treatment for IBD[16,35,36]; an adsorptive carrier-based granulocyte and monocyte apheresis device is used[37]. The clinical efficacy seen following a course of GCAP therapy might be due to the immune modulation as reported[16]. It might involve the mechanism of which the column outflow blood shows a significant level of soluble TNF receptors I and II known to neutralize TNF without invoking TNF-like actions, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)[16].

In 2012, Horie et al[6] conducted a study at multiple centers in Japan (n = 98), and they reported that patients with a WBC count ≥ 104/L who were treated with GCAP had a better prognosis than those not treated with GCAP (P = 0.0006). GCAP is effective for clearing the excess neutrophils and stopping the activated neutrophils from entering the circulatory system, so it is reasonable for preventing liver injury.

In our case, severe liver injury progressed, because the WBC count (predominantly neutrophils) increased up to 50000/μL since the disease onset. Additionally, infectious enteritis, which was difficult to treat by antibiotics, was complicated, and the patient had constant diarrhea. Furthermore, due to the renal failure developed in the course of disease, the amount of antibiotics that can be used is strictly limited and, therefore, we had trouble treating the infection as well. A significantly increased PCT level was observed; however, it was not a helpful marker to control the bacterial infection[38], because chronic alcohol consumption results in an increased endotoxin level in patients with severe AH. In summary, the severe infectious condition and the hepatic failure caused by severe AH was center of the etiology and we were concerning about the disease progress in our patient upon the admission to our hospital. Therefore, we decided to try improving the patient’s condition by using GCAP to decrease the neutrophil circulation with combined HD and PEX prior to the use of CS at initial point.

To date, there are 38 case reports, including the current case, about treating severe AH with GCAP/LCAP; a significant decrease in the WBC after GCAP/LCAP has not been reported, but the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-8 have decreased in some cases[14,17,25,27,30]. Regarding IBD, GCAP inhibits the production of activated neutrophils and pro-inflammatory cytokines[37]. GCAP may be somewhat effective in inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, because the WBC count and levels of IL-6 and TNF-α decreased after GCAP in our case. A previously reported patient was treated with a CS after GCAP, which made GCAP more effective, as GCAP alone did not decrease the levels of cytokines[17]. Among 38 patients, only seven, excluding those with liver transplantation, survived after treatment with only GCAP[30,34]. Further cases and RCTs are needed to determine the effectiveness of GCAP as a therapeutic strategy.

A CS significantly inhibits the production of cytokines; however, the risk of infection and gastrointestinal bleeding remain. In addition, in cases with virus hepatitis and CS resistance, the use of a CS is not always appropriate during the initial stage. GCAP is expected to significantly improve the prognosis of those with severe AH, as the granulocyte and monocyte apheresis device inhibits liver injury caused by activated neutrophils. Hence, GCAP alone or combined with CS may be a novel therapeutic option; however, further study is required.

Liver failure caused by severe alcoholic hepatitis (AH).

Severe AH.

Laboratory data and the diagnostic criteria based diagnosis.

Acute renal failure, sepsis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and endotoxemia.

Severe hepatomegaly.

Granulocytapheresis (GCAP).

Corticosteroids (CS) have shown efficacy in patients with AH by inhibiting the production of cytokines to date.

GCAP.

The authors presented here the case successfully treated with GCAP without using CS because of severe infectious status.

The paper reports a potentially interesting and important study. Overall, the paper is clear and well written. The presented data are easy to understand.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Grattagliano I, Saniabadi AR, Swierczynski J S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Takada A, Tsutsumi M. National survey of alcoholic liver disease in Japan (1968-91). J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;10:509-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lucey MR, Mathurin P, Morgan TR. Alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2758-2769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 659] [Cited by in RCA: 687] [Article Influence: 42.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Forrest E, Mellor J, Stanton L, Bowers M, Ryder P, Austin A, Day C, Gleeson D, O’Grady J, Masson S. Steroids or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis (STOPAH): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mathurin P, O’Grady J, Carithers RL, Phillips M, Louvet A, Mendenhall CL, Ramond MJ, Naveau S, Maddrey WC, Morgan TR. Corticosteroids improve short-term survival in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis: meta-analysis of individual patient data. Gut. 2011;60:255-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 299] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Forrest EH, Evans CD, Stewart S, Phillips M, Oo YH, McAvoy NC, Fisher NC, Singhal S, Brind A, Haydon G. Analysis of factors predictive of mortality in alcoholic hepatitis and derivation and validation of the Glasgow alcoholic hepatitis score. Gut. 2005;54:1174-1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Horie Y. Granulocytapheresis and plasma exchange for severe alcoholic hepatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27 Suppl 2:99-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Thursz MR, Richardson P, Allison M, Austin A, Bowers M, Day CP, Downs N, Gleeson D, MacGilchrist A, Grant A. Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1619-1628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 526] [Cited by in RCA: 552] [Article Influence: 55.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Altamirano J, Fagundes C, Dominguez M, García E, Michelena J, Cárdenas A, Guevara M, Pereira G, Torres-Vigil K, Arroyo V. Acute kidney injury is an early predictor of mortality for patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:65-71.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liangpunsakul S. Clinical characteristics and mortality of hospitalized alcoholic hepatitis patients in the United States. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:714-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Horie Y, Ishii H, Hibi T. Severe alcoholic hepatitis in Japan: prognosis and therapy. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:251S-258S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Thursz M, Forrest E, Roderick P, Day C, Austin A, O’Grady J, Ryder S, Allison M, Gleeson D, McCune A. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of STeroids Or Pentoxifylline for Alcoholic Hepatitis (STOPAH): a 2 × 2 factorial randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19:1-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Singh S, Murad MH, Chandar AK, Bongiorno CM, Singal AK, Atkinson SR, Thursz MR, Loomba R, Shah VH. Comparative Effectiveness of Pharmacological Interventions for Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:958-70.e12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Morris JM, Dickson S, Neilson M, Hodgins P, Forrest EH. Granulocytapheresis in the treatment of severe alcoholic hepatitis: a case series. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:457-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kamimura K, Imai M, Sakamaki A, Mori S, Kobayashi M, Mizuno K, Takeuchi M, Suda T, Nomoto M, Aoyagi Y. Granulocytapheresis for the treatment of severe alcoholic hepatitis: a case series and literature review. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:482-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Horie Y, Yamagishi Y, Ebinuma H, Hibi T. Therapeutic strategies for severe alcoholic hepatitis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2011;35:738-744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Saniabadi AR, Tanaka T, Ohmori T, Sawada K, Yamamoto T, Hanai H. Treating inflammatory bowel disease by adsorptive leucocytapheresis: a desire to treat without drugs. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9699-9715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ma X, Naganuma A, Sato H, Kaburagi D, Arai R, Hosonuma K, Yuasa K, Maruta S, Tomaru Y, Takagi H. A case of severe alcoholic hepatitis successfully treated by multidisciplinary treatment, including leukocytapheresis [in Japanese]. Kanzo. 2013;54:765-773. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yoshizawa K. [Case report]. Therapeutics. 2007;41:413-416. |

| 19. | Szabo G, Bala S, Petrasek J, Gattu A. Gut-liver axis and sensing microbes. Dig Dis. 2010;28:737-744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ramaiah SK, Jaeschke H. Role of neutrophils in the pathogenesis of acute inflammatory liver injury. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35:757-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bautista AP. Neutrophilic infiltration in alcoholic hepatitis. Alcohol. 2002;27:17-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rambaldi A, Saconato HH, Christensen E, Thorlund K, Wetterslev J, Gluud C. Systematic review: glucocorticosteroids for alcoholic hepatitis--a Cochrane Hepato-Biliary Group systematic review with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses of randomized clinical trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:1167-1178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Louvet A, Diaz E, Dharancy S, Coevoet H, Texier F, Thévenot T, Deltenre P, Canva V, Plane C, Mathurin P. Early switch to pentoxifylline in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis is inefficient in non-responders to corticosteroids. J Hepatol. 2008;48:465-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Parker R, Armstrong MJ, Corbett C, Rowe IA, Houlihan DD. Systematic review: pentoxifylline for the treatment of severe alcoholic hepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:845-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Narita R, Sasakura S, Yokota M, Koto K, Okada M, Tamagawa K, Sadamoto K, Koyanagi T, Shinomiya S, Iguchi H. Successful treatment of severe alcoholic hepatitis with plasma exchange and leukapheresis--report of a case. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1998;95:51-55. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Kamimura K, Kobayashi M, Mori S, Yanagisawa Y. A case of severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with Granulocytapheresis. Kanzo. 2002;43:316-321. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Tsuji Y, Kumashiro R, Ishii K, Arinaga T, Sakamoto Y, Tanabe R, Ogata K, Koga Y, Ide T, Ono N. Severe alcoholic hepatitis successfully treated by leukocytapheresis: a case report. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:26S-31S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Naito M, Horiike S, Iwasa M, Ikoma J, Kaito M, Adachi Y. [Severe alcoholic hepatitis resulting in liver transplantation: the first case in Japan]. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 2005;94:753-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Okubo K, Yoshizawa K, Okiyama W, Kontani K, Muto H, Umemura T, Ichijo T, Matsumoto A, Tanaka E, Hora K. Severe alcoholic hepatitis with extremely high neutrophil count successfully treated by granulocytapheresis. Intern Med. 2006;45:155-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ikeda Y, Sato Y. Case (Article in Japanese). Rinshoshokakinaika. 2008;23:507-512. |

| 31. | Ota Y, Sasada Y, Nakahodo J, Matsuhashi T, Koide S, Kikuyama M. A case of severe alcoholic hepatitis successfully treated by granulocytapheresis. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2009;106:1778-1782. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Kumashiro R, Koga Y, Kuwahara R, Ide T, Hino T, Tanaka K, Hisamochi A, Ogata K, Takao Y, Koga H. Granulocytapheresis (GCAP) for severe alcoholic hepatitis-A preliminary report. Hepatol Res. 2006;36:229-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Mori S, Yamagishi Y. Survive of severe alcoholic hepatitis with granulocyte and monocyte apheresis (Article in Japanese). Alcohol Biomed Res. 2004;24:114-119. |

| 34. | Umeda R, Horie Y. Consideration about after course and outcome as a novel therapeutic intervention in severe alcoholic hepatitis (Article in Japanese). Alcohol Biomed Res. 2012;31:66-70. |

| 35. | Sakuraba A, Motoya S, Watanabe K, Nishishita M, Kanke K, Matsui T, Suzuki Y, Oshima T, Kunisaki R, Matsumoto T. An open-label prospective randomized multicenter study shows very rapid remission of ulcerative colitis by intensive granulocyte and monocyte adsorptive apheresis as compared with routine weekly treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2990-2995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Kashiwagi N, Sugimura K, Koiwai H, Yamamoto H, Yoshikawa T, Saniabadi AR, Adachi M, Shimoyama T. Immunomodulatory effects of granulocyte and monocyte adsorption apheresis as a treatment for patients with ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:1334-1341. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Saniabadi AR, Hanai H, Takeuchi K, Umemura K, Nakashima M, Adachi T, Shima C, Bjarnason I, Lofberg R. Adacolumn, an adsorptive carrier based granulocyte and monocyte apheresis device for the treatment of inflammatory and refractory diseases associated with leukocytes. Ther Apher Dial. 2003;7:48-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Becker KL, Snider R, Nylen ES. Procalcitonin in sepsis and systemic inflammation: a harmful biomarker and a therapeutic target. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;159:253-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |