Published online Jun 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i17.5732

Peer-review started: October 28, 2021

First decision: December 27, 2021

Revised: January 9, 2022

Accepted: April 9, 2022

Article in press: April 9, 2022

Published online: June 16, 2022

Processing time: 223 Days and 19.9 Hours

Palato-radicular groove (PRG) is defined as an anomalous formation of teeth. The etiology of PRG remains unclear. The prognosis of a tooth with a PRG is unfavorable. The treatment of combined periodontal-endodontic lesions requires multidisciplinary management to control the progression of bone defects. Some researchers reported cases that had short-term observations. The management of teeth with PRGs is of great clinical significance. However, to date, no case reports have been documented on the use of bone regeneration and prosthodontic treatment for PRGs.

This case reported the management of a 40-year-old male patient with the chief complaint of slight mobility and abscess in the upper right anterior tooth for 15 d and was diagnosed with type II PRG of tooth 12 with combined endodontic-periodontal lesions. The accumulation of plaque and calculus caused primary periodontitis and a secondary endodontic infection. A multidisciplinary mana

This report indicates that bone regeneration and prosthodontic treatment may contribute to the long-term favorable prognosis of teeth with PRGs.

Core Tip: The prognosis of a tooth with a palato-radicular groove (PRG) is unfavorable. The treatment of combined periodontal-endodontic lesions requires multidisciplinary management to control the progression of bone defects. Some researchers reported cases that had short-term observations. However, to date, no case reports have described the use of both bone regeneration treatment and prosthodontic treatment for PRG. Herein, we report a patient with PRG who was treated with bone regeneration and prosthodontic treatments, and 2 years of follow-up showed a good prognosis. This report indicates that bone regeneration and prosthodontic treatment may contribute to the long-term favorable prognosis of teeth with PRGs.

- Citation: Ling DH, Shi WP, Wang YH, Lai DP, Zhang YZ. Management of the palato-radicular groove with a periodontal regenerative procedure and prosthodontic treatment: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(17): 5732-5740

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i17/5732.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i17.5732

Palato-radicular groove (PRG) is defined as an anomalous formation of teeth that begins in the central fossa of the maxillary incisors, extends over the cingulum, and continues apically to varying depths and distances of the root surface[1]. The etiology of PRGs remains unclear. The most common proposals of PRG development include the following four hypotheses: (1) An abnormality in embryonic development, such as in folding of Hertwig’s epithelial root sheath; (2) a variant of dens invaginatus; (3) genetic alteration; and (4) an attempt to form another root[2,3].

PRG usually occurs on the palatal side of the maxillary incisors that do not have dental caries or trauma[4,5]. The incidence of PRG ranges from 0.9% to 9.6% in extracted maxillary incisors[6,7] and from 2.8% to 10% in clinical studies[4,8]. Khan et al[9] reported a higher incidence of PRG in lateral incisors (13.4%) than in central incisors (7.6%). Various factors could account for this difference in prevalence rate, such as different diagnostic criteria, differences in examination methodologies, or ethnic/racial differences.

Micro-computed tomography (CT) and cone-beam CT have been widely used to observe lateral incisors with PRG. Gu[10] classified PRG into three types according to the depth and length of the radicular groove. Type I PRG has a short groove with limited length to the coronal third of the root. Type II PRG has a long groove, and its length is beyond the coronal third of the root, while its depth is often shallow. This implies that the root canal system of the tooth with a type II PRG is often simple. Type III PRG has a long and deep groove, which indicates a complex root canal system. However, this classificationn cannot be accurately applied in clinical practice because of complex cases and extremely small structures[11].

Teeth with deep grooves are more likely to show signs of periodontal disease such as bleeding, deep pocket depth, and endodontic-periodontal lesions[12]. Some researchers believe that there are multiple communication channels that exist between periodontal tissues and pulp, such as the apical foramen, accessory foramina, lateral canals, and dentin tubules[3]. Plaque and calculus accumulated in the periodontal pocket may extend into the bottom part of the deep groove with pulpal involvement[13]. The prognosis of a tooth with a PRG is unfavorable. It is influenced by several factors, such as the depth and length of the PRG, the anatomical morphology of the infected root canal system, and the severity of periodontal osseous defects[3].

Multidisciplinary management might be a better approach for treating PRG, but the current evidence is limited. To date, no case reports have observed multidisciplinary management, including endodontic treatment, bone regeneration treatment, and prosthodontic treatment, in the treatment of PRG. This study reports a patient with a type II PRG that was treated with this multidisciplinary approach and his observed prognosis during a 2-year period.

A 40-year-old male patient was admitted to the Department of General Dentistry, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine, with the chief complaint of slight mobility and abscess in the upper right anterior tooth for 15 d.

Slight mobility and abscess in the upper right anterior tooth for 15 d.

He experienced no pain or trauma in this region during the last 10 years.

There was no personal or family history.

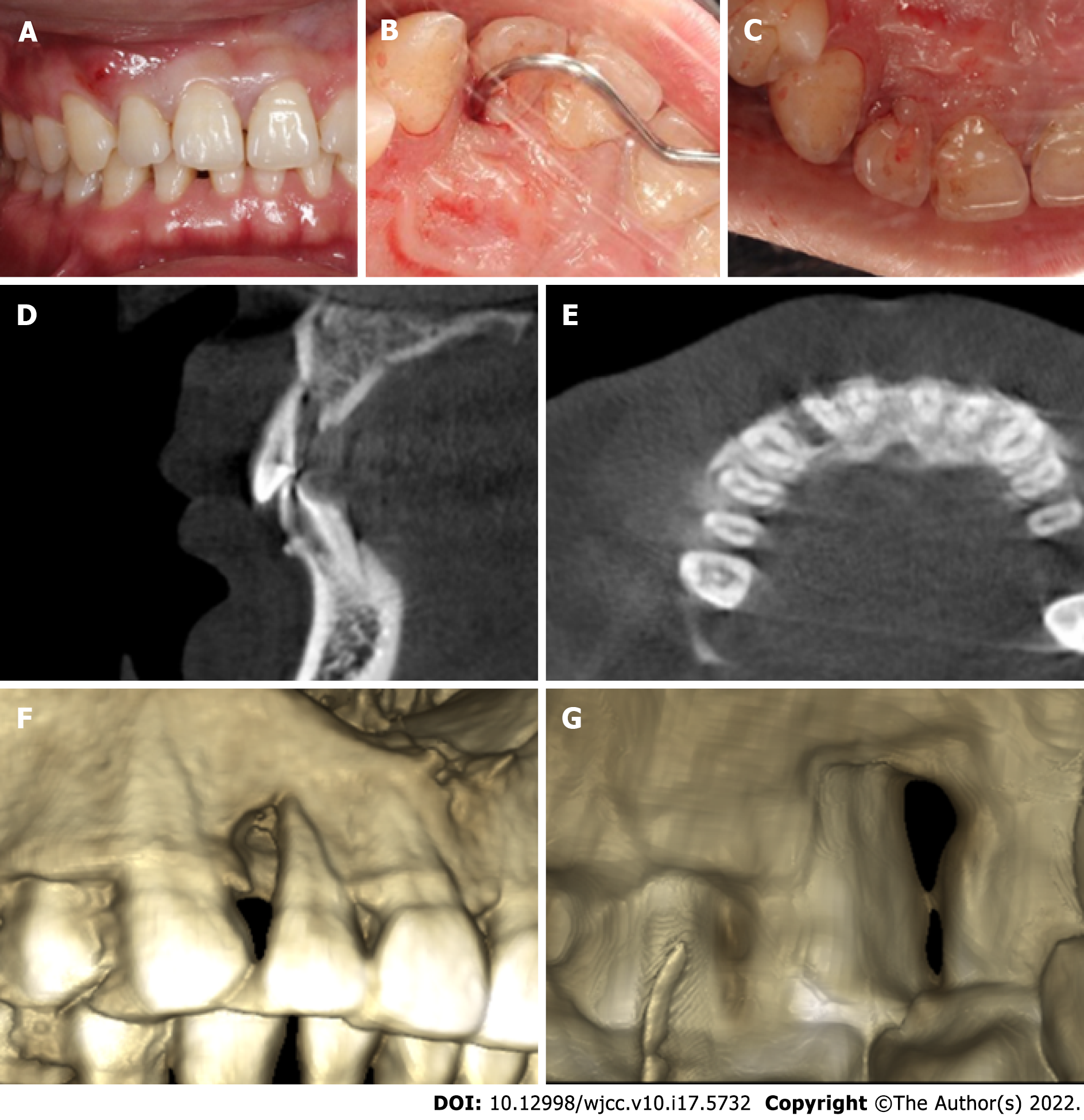

On examination, tooth 12 had an intact crown without defect or fracture, but it did not respond to electric pulp testing (DY310, Denjoy Dental, Changsha, Hunan Province, China). The mobility of tooth 12 was grade I, and it showed a sensitive response to percussion. There was a sinus tract on the buccal gingival surface close to tooth 12 (Figure 1A).

Periodontal examination using a probe (KPC15, Shanghai Kangqiao Dental Instruments Factory, Shanghai, China) revealed a 14 mm depth on the distal side of the root (Figure 1B). The vitality test (Denjoy Dental, Changsha, Hunan Province, China) of tooth 12 was negative. A PRG emerged from the cingulum, which extended to the gingival sulcus and continued disto-apically down to the lingual aspect of the root (Figure 1C).

A cone-beam CT scan (Planmeca Romexis Viewer 4.5.0R, Planmeca Oy, Helsinki, Finland) revealed a radiolucency around the distal and palatal side of the root (Figure 1D and E). Dimensional reconstruction (Asentajankatu 6, FIN-00880, Helsinki, Finland) visualized a large bone defect and a long PRG extending up to the apical part of the tooth (Figure 1F and G).

Based on the patient’s history and clinical and radiographic examination findings, the lesion was diagnosed as a type II PRG with combined endodontic-periodontal lesions. The PRG caused accumulation of plaque and calculus, which in turn caused primary periodontitis and a secondary endodontic infection.

A multidisciplinary management plan was designed, which comprised root canal therapy, groove sealing, periodontal regenerative procedures, and prosthodontic treatment. The patient signed the informed consent form after being informed about the treatment plan and the possible long-term prognosis of tooth 12.

Periodontal nonsurgical treatment was performed to remove the localized calculus. Root canal therapy was started under the isolation of a rubber dam after 1 wk. Cleaning and shaping were performed with K-files (Mani, Tochigi, Japan) and NiTi hand files (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland). The canal was irrigated with 1% sodium hypochlorite and 0.9% normal saline. Canal filling was completed with gutta-percha (Gapadent, Tianjin, China) and iRoot SP (Innovative BioCeramix, Vancouver, BC, Canada) using the cold lateral compaction technique. The access cavity of the crown was filled with composite resin (3 M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, United States).

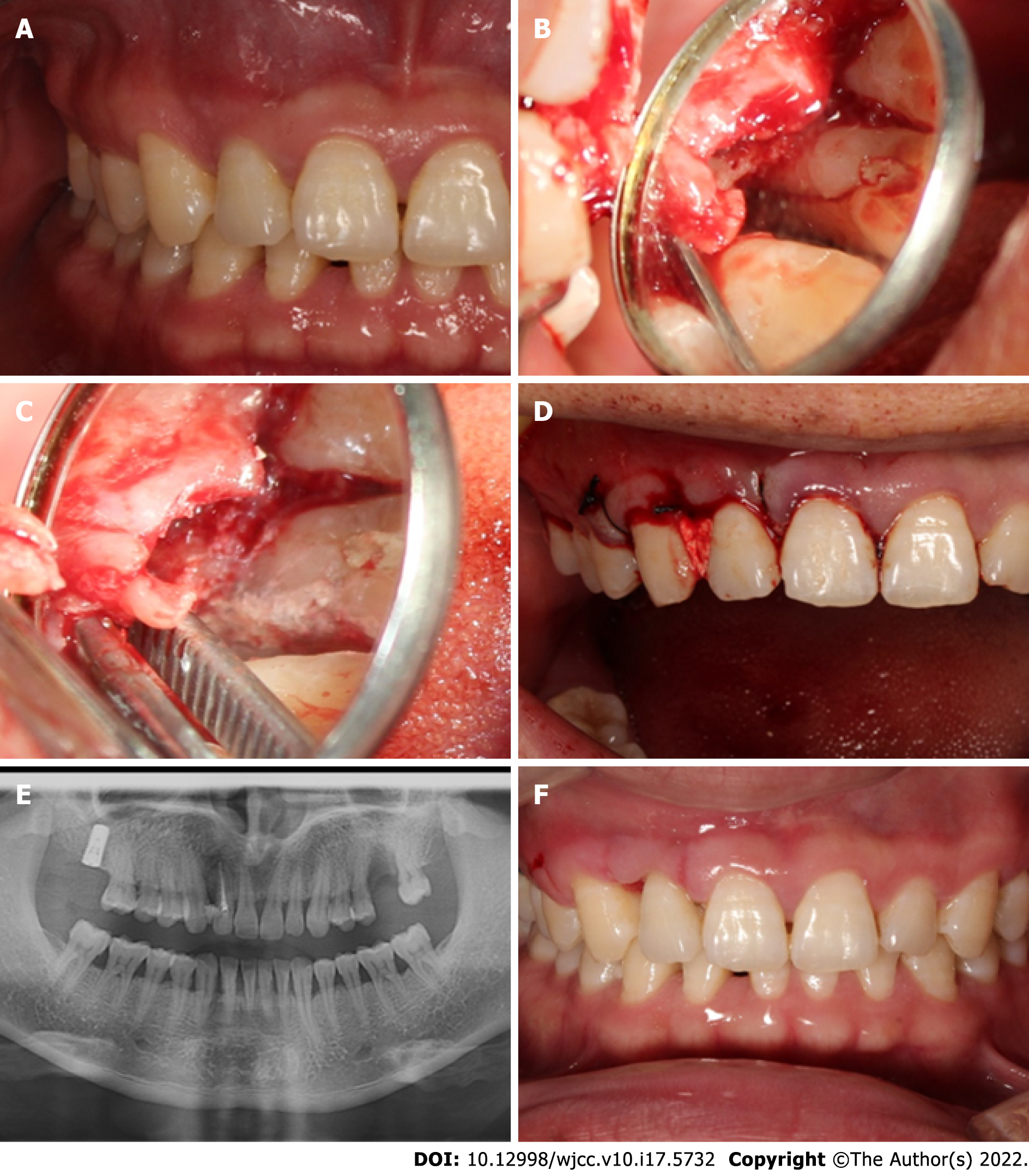

Two weeks later, the sinus tract disappeared just before periodontal surgery (Figure 2A). The surgical area (labiopalatine mucosa of teeth 13-22) was disinfected with 5% povidone-iodine after gargling with 0.2% chlorhexidine for 1 min, followed by local anesthesia with 5 mL of 2% lidocaine mixed with 1:100000 epinephrine. A full-thickness mucoperiosteal flap was reflected from the distal side of tooth 13 to the mesial side of tooth 11. The granulation tissue was curetted, and the surface of the root was planned with gracey curette number 5/6 (Hu-Friedy Mfg. Co., Chicago, IL, United States). After degranulation, a 6 mm × 14 mm pear-shaped defect was exposed (Figure 2B). A deep groove was visible extending to the apical part of the root. This groove was prepared with high-speed round diamond (Mani, Tochigi, Japan) under dental microscopy. Minocycline hydrochloride ointment was then applied for 5 min on the root to remove endotoxin. The area was isolated with a gelatin sponge (Jiangxi Xiangen Medical, Nanchang, Jiangxi Province, China) for hemostasis. The PRG was then sealed completely with iRoot BP Plus (Innovative BioCeramix, Vancouver, BC, Canada) (Figure 2C). Periodontal-guided tissue regeneration was performed using a 0.5 g bone graft (Geistlich Biomaterials, Wolhusen, Switzerland) and a 10 mm × 15 mm resorbable membrane (Geistlich Biomaterials, Wolhusen, Switzerland). The flap was sutured with a 3-0 black silk suture (Huawei Medical, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China), and a periodontal dressing was placed (PULPDENT Corporation, Watertown, MA, United States) (Figure 2D). Postoperative panoramic radiography was performed after 2 h (Figure 2E). Cefuroxime axetil (500 mg twice a day for 3 d) and acetaminophen (325 mg twice a day for 1 d) were prescribed after surgery. The patient had no symptoms or discomfort, and sutures were removed after 8 d (Figure 2F).

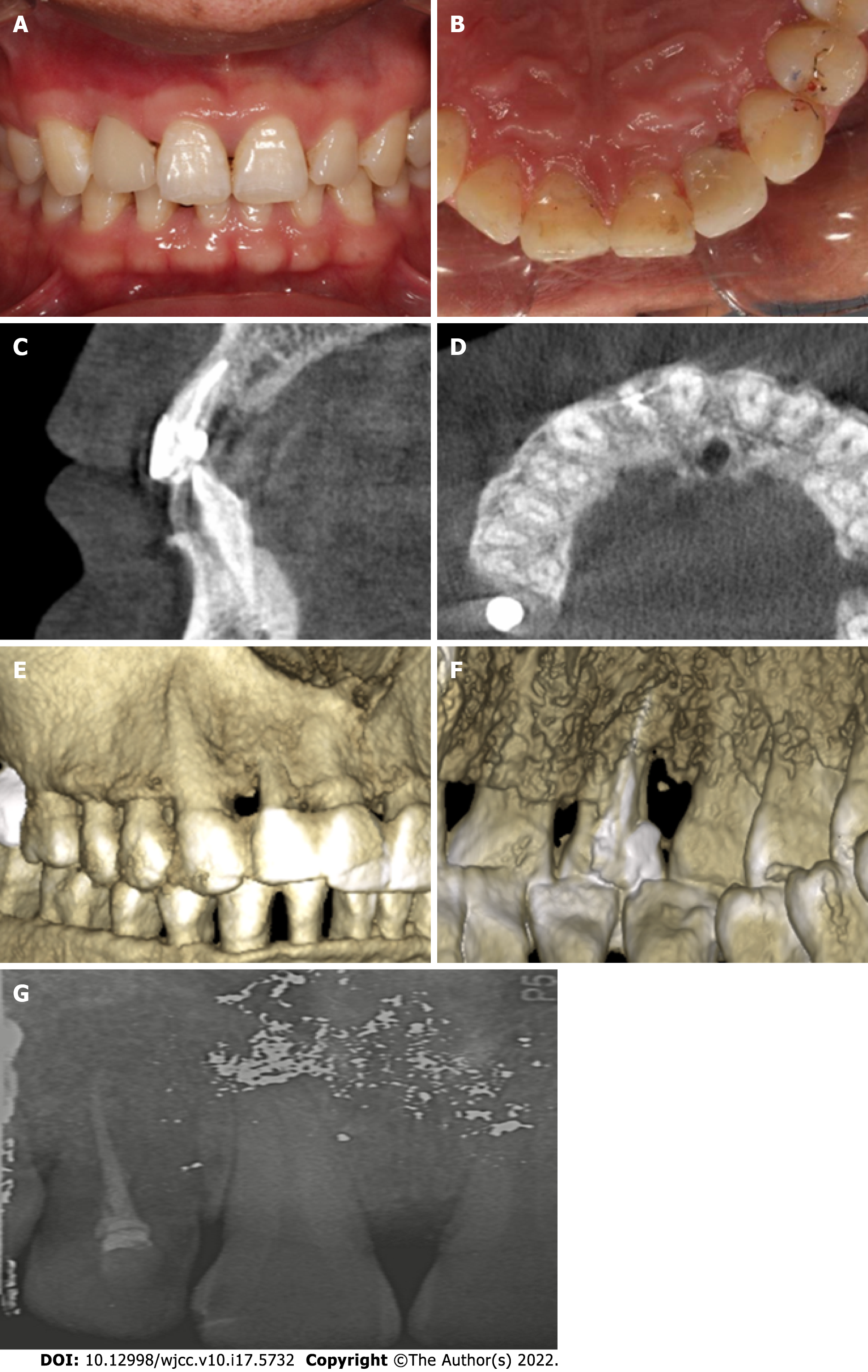

The patient was re-examined at 6 wk, 3 mo, and 1 year, and 2 years after surgery. The healing was uneventful. At 1 year, there was a reduction in the pocket depth from 13 mm to 3 mm without bleeding. To prevent food impaction, veneer preparation was performed for tooth 12, and a lithium disilicate veneer (Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein) was made to close the space between tooth 12 and tooth 13 (Figure 3A and B). Postoperative cone-beam CT at 1 year showed significant bone formation around the tooth under dimensional reconstruction, and the PRG disappeared (Figure 3C and D). Dimensional reconstruction showed that the bone defect around tooth 12 disappeared. The sealing material was stable, and the groove became flat (Figure 3E and F). At 2 years, tooth 12 showed mild inflammation with dental calculus. However, the periapical radiograph confirmed that the alveolar bone around tooth 12 was stable (Figure 3G). Periodontal nonsurgical treatment was performed immediately.

Early diagnosis and treatment of a PRG may significantly improve its prognosis. Without periodontal disease and pulp impairment, conservative treatment, such as sealing the groove, can prevent complications[14]. Based on preoperative imaging findings, the patient was diagnosed with a type II PRG. Usually, shallow grooves are less likely to cause endodontic-periodontal lesions because the communication between the dental pulp and the periodontium is blocked. However, in the present case, the groove of tooth 12 was close to the apical part of the root. The apical foramen and accessory foramina may act as possible communication channels between periodontal infection and the pulp. Interdisciplinary approaches are recommended for managing such situations, such as degranulation of the defect, groove sealing, endodontic treatment, bone regeneration treatment, and prosthodontic treatment[15]. Some unknown variables can significantly influence the oral environment. The use of probiotics[16] and natural compounds[17] can modify clinical and microbiological parameters in periodontal patients. They might also alter the outcomes of the technique described in the present report. All these variables should be considered in future clinical trials. Although sealing the groove in type II PRGs remain controversial, some studies insist that root planning can achieve attachment[14,18]. The final goal of all treatments to make the root surface flat and smooth prevents the formation of plaque and calculus, which could lead to periodontal involvement[19]. There are various therapeutic options available, but the clinical cases are complex and need further exploration.

Many materials have been used for sealing grooves, such as amalgam, composite resin, glass ionomer cement, mineral trioxide aggregate, and iRoot BP plus. Glass ionomer cement has been widely used in the past 10 years, and its advantages include an antibacterial effect, chemical bonding ability, fluoride release property, and ability to attach to epithelial tissue[14,20]. Mineral trioxide aggregates show better biocompatibility. It exhibits lower microleakage when applied to seal the root canal and the periapical tissues[21]. However, the mean setting time of mineral trioxide aggregate is 165.5 min. This implies that mineral trioxide aggregate is unstable and may be washed away during setting[22]. iRoot BP Plus is a convenient and premixed hydraulic bioceramic putty that is newly developed for root canal repair and surgical applications. It shows a shorter setting time and better sealing ability than mineral trioxide aggregates[23]. iRoot BP Plus was also proven to trigger the osteogenic capacity of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells[24]. Hence, we chose iRoot BP Plus as the sealing material. The healing of the tooth was uneventful, and the bone around the defect was stable after 2 years. To date, no studies have reported the results of iRoot BP Plus used in sealing PRGs. The present case may provide a clinical basis for a new application of this material. Additionally, laser[25] and ozone[26] therapies have been proposed for periodontal health, showing promising results. Future reports are required to test these therapies for PRG.

Restoration with porcelain veneers is the most conservative treatment according to the concept of minimally invasive dentistry. The final goals of this restorative treatment are to save tooth structure and restore function and esthetics. However, the aim of restoring the tooth with a veneer in the present case was to close the space between tooth 12 and tooth 13. Consequently, both food impaction and secondary periodontal problems were prevented. After 2 years of follow-up, the color of the veneer and alveolar bone was found to be stable. This suggests that prosthodontic treatment is necessary for the multidisciplinary management of PRG.

Multidisciplinary management might be a better option for optimal clinical outcomes for complex cases. However, when patients have an extensive groove area and severe complications, even a multidisciplinary approach with the combination of conservative treatment and local surgery cannot result in a favorable prognosis. Intentional extraction of a problematic tooth and subsequent reimplantation might be an alternative option for these patients[27]. On the other hand, this case report still deserves further investigation to confirm the actual role of the present multidisciplinary treatment considering the limited sample size.

We report a patient with a type II PRG who was treated with multidisciplinary treatment, including endodontic treatment, bone regeneration treatment, and prosthodontic treatment. The results of a 2-year follow-up indicate that bone regeneration and prosthodontic treatment may contribute to the long-term favorable prognosis of teeth with PRGs, which deserves further investigation.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Dentistry, oral surgery and medicine

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Rakhshan V, Iran; Rakhshan V, Iran; Scribante A, Italy; Scribante A, Italy S-Editor: Guo XR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Guo XR

| 1. | Gadagi JS, Elavarasu S, Ananda D, Murugan T. Successful treatment of osseous lesion associated with palatoradicular groove using local drug delivery and guided tissue regeneration: A report of two cases. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2012;4:S157-S160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ennes JP, Lara VS. Comparative morphological analysis of the root developmental groove with the palato-gingival groove. Oral Dis. 2004;10:378-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim HJ, Choi Y, Yu MK, Lee KW, Min KS. Recognition and management of palatogingival groove for tooth survival: a literature review. Restor Dent Endod. 2017;42:77-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kishan KV, Hegde V, Ponnappa KC, Girish TN, Ponappa MC. Management of palato radicular groove in a maxillary lateral incisor. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2014;5:178-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hungund S, Kumar M. Palato-radicular groove and localized periodontitis: a series of case reports. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2010;11:056-062. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Aksoy U, Kermeoğlu F, Kalender A, Eren H, Kolsuz ME, Orhan K. Cone-beam computed tomography evaluation of palatogingival grooves: A retrospective study with literature review. Oral Radiol. 2017;33:193-198. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Storrer CM, Sanchez PL, Romito GA, Pustiglioni FE. Morphometric study of length and grooves of maxillary lateral incisor roots. Arch Oral Biol. 2006;51:649-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Iqbal N, Tirmazi SM, Majeed HA, Munir MB. Prevalence of palato gingival groove in maxillary lateral incisors. Pak Oral Dent J. 2011;31:424-426. |

| 9. | Khan AM, Shah SA, Alam F, Ullah A, Humayun A, Nisar S, Mian FM. Frequency of palatogingival groove in maxillary incisors. Pak Oral Dent J. 2019;39:82-84. |

| 10. | Gu YC. A micro-computed tomographic analysis of maxillary lateral incisors with radicular grooves. J Endod. 2011;37:789-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tan X, Zhang L, Zhou W, Li Y, Ning J, Chen X, Song D, Zhou X, Huang D. Palatal Radicular Groove Morphology of the Maxillary Incisors: A Case Series Report. J Endod. 2017;43:827-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gandhi A, Kathuria A, Gandhi T. Endodontic-periodontal management of two rooted maxillary lateral incisor associated with complex radicular lingual groove by using spiral computed tomography as a diagnostic aid: a case report. Int Endod J. 2011;44:574-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Katwal D, Fiorica JK, Bleuel J, Clark SJ. Successful Multidisciplinary Management of an Endodontic-Periodontal Lesion Associated With a Palato-Radicular Groove: A Case Report. Clin Adv Periodontics. 2020;10:88-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Corr A-Faria P, Alcântara CE, Santos CR, Marques LS, Ramos-Jorge ML. Palatal radicular groove: clinical implications of early diagnosis and surgical sealing. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2011;29:S92-S94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Miao H, Chen M, Otgonbayar T, Zhang SS, Hou MH, Wu Z, Wang YL, Wu LG. Papillary reconstruction and guided tissue regeneration for combined periodontal-endodontic lesions caused by palatogingival groove and additional root: a case report. Clin Case Rep. 2015;3:1042-1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Butera A, Gallo S, Maiorani C, Molino D, Chiesa A, Preda C, Esposito F, Scribante A. Probiotic Alternative to Chlorhexidine in Periodontal Therapy: Evaluation of Clinical and Microbiological Parameters. Microorganisms. 2020;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Costa-Pinto AR, Lemos AL, Tavaria FK, Pintado M. Chitosan and Hydroxyapatite Based Biomaterials to Circumvent Periprosthetic Joint Infections. Materials (Basel). 2021;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Schäfer E, Cankay R, Ott K. Malformations in maxillary incisors: case report of radicular palatal groove. Endod Dent Traumatol. 2000;16:132-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mahmood A, Sajid M, Jamil M, Tahir MW. Palato Gingival Groove. Prof Med J. 2019;26:559-562. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Antonson SA, Antonson DE, Brener S, Crutchfield J, Larumbe J, Michaud C, Yazici AR, Hardigan PC, Alempour S, Evans D, Ocanto R. Twenty-four month clinical evaluation of fissure sealants on partially erupted permanent first molars: glass ionomer versus resin-based sealant. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;143:115-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Patro S, MohaPatra S, MiShra SJJoC, Research D. Comparative evaluation of apical microleakage of retrograde cavities filled with glass ionomer cement, light-cured composite, mineral trioxide aggregate and biodentine. J Clin Diag Res. 2019;13:18-22. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Goel M, Bala S, Sachdeva G. Comperative evaluation of MTA, calcium hydroxide and portland cement as a root end filling materials: a comprehensive review. Indian J Dent Sci. 2011;3:83-88. |

| 23. | Aydemir S, Cimilli H, Gerni PM, Bozkurt A, URUCOGLU H, Chandler N, Kartal N. Comparison of the sealing ability of biodentine, iRoot BP plus and mineral trioxide aggregate. Cumhur Dent J. 2016;19:166-171. |

| 24. | Lu J, Li Z, Wu X, Chen Y, Yan M, Ge X, Yu J. iRoot BP Plus promotes osteo/odontogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells via MAPK pathways and autophagy. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tualzik T, Chopra R, Gupta SJ, Sharma N, Khare M, Gulati L. Effects of ozonated olive oil and photobiomodulation using diode laser on gingival depigmented wound: A randomized clinical study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2021;25:422-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Butera A, Gallo S, Pascadopoli M, Luraghi G, Scribante A. Ozonized Water Administration in Peri-Implant Mucositis Sites: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Appl Sci. 2021;11:7812. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Forero-López J, Gamboa-Martínez L, Pico-Porras L, Niño-Barrera JL. Surgical management with intentional replantation on a tooth with palato-radicular groove. Restor Dent Endod. 2015;40:166-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |