Published online Aug 8, 2017. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v6.i3.149

Peer-review started: January 16, 2017

First decision: March 28, 2017

Revised: May 24, 2017

Accepted: June 7, 2017

Article in press: June 13, 2017

Published online: August 8, 2017

Processing time: 199 Days and 16.5 Hours

To establish how neonatal units in England and Wales currently confirm longline tip position, immediately after insertion of a longline.

We conducted a telephone survey of 170 neonatal units (37 special care baby units, 81 local neonatal units and 52 neonatal intensive care units) across England and Wales over the period from January to May 2016. Data was collected on specifically designed proformas. We gathered information on the following: Unit Level designation; whether the unit used longlines and specific type used? Modality used to confirm longline tip position? Whether guide wires were routinely removed and contrast injected to determine longline position? The responders were primarily senior nurses.

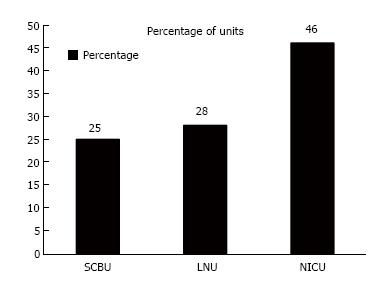

We had 100% response rate. Out of the total neonatal units surveyed (170) in England and Wales, 141 units (83%) used longlines. Fifty-five out of 81 local neonatal units (68%) using longlines, used ones that came with guide wires; a similar percentage of neonatal intensive care units, i.e., 31 out of 52 units (60%) did the same. All of those units used radiography, plain X-rays, to establish longline tip position. Out of 55 local neonatal units using longlines with guide wires, 42 (76%) were not removing wire to use contrast while this figure was 58% (18 out of 31 units) for neonatal intensive care units. Overall, only 49 out of 141 units (35%) of the units using longlines were using contrast. However it was interesting to note that use of contrast increased as one moved from special care baby units (25%, 2 out of 8 units) to local neonatal units (28%, 23 out of 81 units) and neonatal intensive care units level (46%, 24 out of 52 units) designation.

Neonatal units in England and Wales are overwhelmingly relying on plain radiographs to assess longline tip position immediately after insertion. Despite evidence of its usefulness, and in the absence of perhaps more accurate methods of assessing longline tip position in a reliable and consistent way, i.e., ultrasonography, contrast is only used in a third of units.

Core tip: Accurate placement of longlines is important as malposition can lead to serious complications. A number of different techniques and specialised modalities have been described in the literature. A readily available adjunct to plain radiography, shown to help avoid catheter malposition, is the use of contrast. Our survey shows that the majority of neonatal units in England and Wales are overwhelmingly reliant on plain radiographs for confirmation of longline position. Despite evidence of its usefulness and in the absence of perhaps more accurate methods of assessing longline tip position in a reliable and consistent way, e.g., ultrasonography, contrast is only used in a third of units to confirm longline position immediately after insertion of a longline.

- Citation: Arunoday A, Zipitis C. Confirming longline position in neonates - Survey of practice in England and Wales. World J Clin Pediatr 2017; 6(3): 149-153

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v6/i3/149.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v6.i3.149

Percutaneous central venous lines (longlines) are commonly used in neonatal practice. A longline is a fine plastic (silastic) tube 10 to 30 cm long that is threaded into one of the newborn’s veins, usually in the upper or lower limbs, to reach a point where the vein becomes much larger, usually just outside the heart. It can be used to deliver parenteral nutrition and for the safe and uninterrupted administration of clinically essential or locally toxic solutions. The higher blood flow in the larger veins leads to a decrease in the risk of complications from the plastic itself and also the infused solutions. A longline can stay in place for several weeks, which reduces the number of times a newborn baby needs to have a drip inserted. Correct placement is important to avoid complications such as extravasation of fluids into pleural, peritoneal, pericardial and subcutaneous compartments[1].

Different methods are used to assess longline tip position. The most common, plain radiography is plagued with concerns about poor intra- and inter-observer reliability[2]. Other modalities, e.g., echocardiography[3] and CT[4] might be more reliable but are not readily available in most units. Use of contrast, an injectable solution that can be used to improve radio-opacity of the longline by injecting into the longline in sufficient volume to fill the connecting device and catheter, can help with recognition of unusual patterns of contrast medium dispersal and lead to easier identification of catheter malposition when combined with radiographs[5,6]. Although it is recognized that even with use of contrast precise localization of longline tips can be difficult, its use improves the likelihood that observers can see the tip more reliably and reduces inter-observer variability as regards to the anatomical placement of the tip[7].

Discussions with relevant departments in our Institution, led to the conclusion that this study was a review of practice and hence no ethical approval was necessary. After registration with the audit department of our Institution, we conducted a telephone survey of all neonatal units in England and Wales. The aim was to establish the current practice for confirming longline position immediately after insertion of a longline. All responses were collected on specifically designed proformas. We gathered information on Unit Level designation, whether the unit used longlines and specific type(s) used, the modality used to confirm longline tip position, and whether guide wires were routinely removed and contrast injected to determine longline position. A guidewire is a thin wire that comes already inserted into a longline to increase rigidity which helps with line insertion and also helps with better line visualization with plain radiography as it is radio-opaque.

We identified 177 neonatal units in England and Wales in Feb-May 2016. Out of those, 7 units had either closed or merged, leaving 170 individual units; 37 special care baby units (SCBUs), 81 local neonatal units (LNUs) and 52 neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). Responses were collected on specifically designed proformas. The responders were primarily nursing shift leaders. One hundred and forty-one units used long-lines and all units used plain radiography (single view) to establish longline tip position. We had 100% response rate. Out of the total neonatal units surveyed (170) in England and Wales, 141 units (83%) used longlines.

Fifty-five out of 81 LNUs (68%) using longlines, used ones that came with guide wires; a similar percentage of NICUs 60% (31 out of 52 units) did the same.

Focusing on those units using longlines with guide wires, 76% (42 out of 55 units) of LNUs were not removing wire to use contrast; this figure was 58% (18 out of 31 units) for NICUs.

It was interesting to note that use of contrast increased as one moved from SCBUs (25%, 2 out of 8 units) to LNUs (28%, 23 out of 81 units) and NICUs level (46%, 24 out of 52 units) designation.

Overall, only 49 out of 141 units (35%) of the units using longlines were using contrast, with the proportion increasing with level designation as can be seen in Figure 1 and as mentioned above.

Percutaneous central venous lines are commonly used in neonatal practice. The position of these lines is important because incorrect placement may be associated with complications. It is therefore essential that the paediatricians/radiologists are able to recognize sub-optimally positioned catheters in their radiographic assessment to avoid such complications. Serious complications include extravasation of fluids into pleural, peritoneal, pericardial and subcutaneous compartments.

There are a number of case reports where longline migration has caused pericardial effusion and tamponade. The fluid aspirated was confirmed to be consistent with parenteral nutrition which was delivered by longline[8-10]. Even death has been reported in neonates due to complications such as myocardial perforation and cardiac tamponade related to percutaneously placed longlines[11,12].

A case series done over a 5 year period in neonates identified an incidence rate of 1.1% of extravasation in the study (pericardial and pleural effusion). The reported mortality for pericardial effusions in this study was 67%[13].

In a case report of an intra-abdominal extravasation of parenteral nutrition, the authors suggest that complication could have been prevented by optimal placement of catheter tip[14]. De et al[15] presented the case of a preterm infant in whom a longline had inadvertently been placed into the left ascending lumbar vein. When such catheters enter the spinal canal, paraplegia and even death can ensue[16]. In view of the above known infrequent but serious complications, it is vital that all line placements should be confirmed as accurately as possible. As stated above, there are studies showing poor intra- and inter-observer reliability when radiographs are used to assess longline tips and the major determinant of line repositioning was the perceived location. There are many studies where different modalities have been used to suggest confirmation of line tip as accurately as possible. Examples are two-view radiographs[17], use of echocardiography, CT radiography, intracavity ECG[18], transthoracic ultrasonography[19], horizontal beam technique[20], and use of lateral radiographs[21]. Use of ultrasound can be very helpful but it is user dependant. Longline tip position is the important factor in determining the correct position of the catheter; however one can be misled or misguided if the plain supine X-ray is solely relied upon[22]. This is because X-rays are viewed in a two dimensional form and unless contrast is given it will be difficult to perceive the exact localisation of tip position.

Some studies as listed above suggest that contrast should be used routinely in the assessment of longline position in the neonate, because it helps in easier identification of catheter malposition by recognizing unusual contrast medium dispersal. One should acknowledge the existence of reports where use of contrast failed to identify abnormal positioning of the catheter tip in the abdomen leading to harm in the neonate[23]. Having said that, the specific methodology of contrast injection was not described in this case report and some of the largest case series published on the subject support use of contrast during radiographic exposure and back it up with reduced complication rates[24]. Although it is recognized that even with the use of contrast precise localization of longline tips can be difficult, its use has been shown to reduce inter-observer variability.

Our study had 100% response rate and it therefore gives a full and accurate picture of current reality in English and Welsh Neonatal Units. Accurate placement of longlines is important as malposition can lead to serious complications. A number of different techniques and specialized modalities have been described in the literature. Despite evidence showing poor intra- and inter-observer reliability, our review suggests that we are still overwhelmingly relying on plain radiographs to identify longline tip position. Contrast has been proposed to be superior to plain radiographs in the confirmation of the line tip position; however, our study shows that neonatal units in England and Wales do not currently use this as widely as one might have expected. Contrast is used in just over a 1/3 of units though it is interesting to note the trend towards its use with increasing level designation. There might indeed be more accurate modalities in existence but, on the whole, these may need expertise or equipment that might not be available at the point of care in real time. Therefore, use of contrast should be explored further and be the focus of clinical trials exploring its reliability and safety. It might also be useful to look at the rates of adverse longline events in those units that use contrast vs those that do not.

Paula Madden, Clinical audit officer, Royal Albert Edward Infirmary Hospital, Wigan Ln, Wigan, WN1 2NN.

Percutaneous central venous lines (longlines) are commonly used in neonatal practice. A longline is a fine plastic (silastic) tube 10 to 30 cm long that is threaded into one of the newborn’s veins, usually in the upper or lower limbs, to reach a point where the vein becomes much larger, usually just outside the heart. It can be used to deliver parenteral nutrition and for the safe and uninterrupted administration of clinically essential or locally toxic solutions. The higher blood flow in the larger veins leads to a decrease in the risk of complications from the plastic itself and also the infused solutions. A longline can stay in place for several weeks, which reduces the number of times a newborn baby needs to have a drip inserted. Correct placement is important to avoid complications such as extravasation of fluids into pleural, peritoneal, pericardial and subcutaneous compartments. Different methods are used to assess longline tip position. The most common, plain radiography is plagued with concerns about poor intra- and inter-observer reliability. Other modalities, e.g., echocardiography and CT might be more reliable but are not readily available in most units. Use of contrast can help with recognition of unusual patterns of contrast medium dispersal and lead to easier identification of catheter malposition when combined with radiographs.

Despite evidence showing poor intra- and inter-observer reliability, the review suggests that clinicians are still overwhelmingly relying on plain radiographs to identify longline tip position. Contrast has been proposed to be superior to plain radiographs in the confirmation of the line tip position; however, the study shows that neonatal units in England and Wales do not currently use this as widely as one might have expected. Contrast is used in just over a 1/3 of units though it is interesting to note the trend towards its use with increasing level designation. There might indeed be more accurate modalities in existence but, on the whole, these may need expertise or equipment that might not be available at the point of care in real time. Therefore, use of contrast should be explored further and be the focus of clinical trials exploring its reliability and safety. It might also be useful to look at the rates of adverse longline events in those units that use contrast vs those that do not.

The study had 100% response rate and it therefore gives a full and accurate picture of current reality in English and Welsh Neonatal Units. Accurate placement of longlines is important as malposition can lead to serious complications. A number of different techniques and specialized modalities have been described in the literature. A readily available adjunct to plain radiography, shown to help avoid catheter malposition, is the use of contrast. The survey shows that the majority of neonatal units in England and Wales are still, overwhelmingly, relying on plain radiographs to confirm longline position. Despite evidence of its usefulness, contrast is used by about a third of neonatal units to confirm longline position immediately after insertion of a longline.

Despite evidence showing poor intra- and inter-observer reliability, the review suggests that authors are still overwhelmingly relying on plain radiographs to identify longline tip position. Contrast has been proposed to be superior to plain radiographs in the confirmation of the line tip position; however, the study shows that neonatal units in England and Wales do not currently use this as widely as one might have expected. Contrast is used in just over a 1/3 of units though it is interesting to note the trend towards its use with increasing level designation. There might indeed be more accurate modalities in existence but, on the whole, these may need expertise or equipment that might not be available at the point of care in real time. Therefore, use of contrast should be explored further and be the focus of clinical trials exploring its reliability and safety. It might also be useful to look at the rates of adverse longline events in those units that use contrast vs those that do not.

Longline: A fine plastic (silastic) tube, usually 10 cm to 30 cm long, that is threaded into one of the baby’s small veins usually in the arm or leg and towards the wider central veins; Guidewire: A thin wire that comes already inserted into a longline to increase rigidity, which helps with line insertion, and also with better line visualization during plain radiography as it is radiopaque; Contrast: A radiopaque substance used to improve visualisation of a structure, in this case the longline, as it is injected into the longline during radiographic exposure in sufficient volume to fill the connecting device and catheter and leave a blush of contrast visible at the catheter tip.

Authors analyzed use of different methods in confirming long line position in newborns. This is a worthy audit of contemporary practice in England and Wales.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Pediatrics

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Donatella A, Lin J, Spasojevic SD, Zhang BH S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Fuentealba TI, Retamal CA, Ortiz CG, Pérez RM. [Radiographic assessment of catheters in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU)]. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2014;85:724-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Odd DE, Battin MR, Kuschel CA. Variation in identifying neonatal percutaneous central venous line position. J Paediatr Child Health. 2004;40:540-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tauzin L, Sigur N, Joubert C, Parra J, Hassid S, Moulies ME. Echocardiography allows more accurate placement of peripherally inserted central catheters in low birthweight infants. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102:703-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Evans A, Natarajan J, Davies CJ. Long line positioning in neonates: does computed radiography improve visibility? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89:F44-F45. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Filan PM, Salek-Haddadi Y, Nolan I, Sharma B, Rennie JM. An under-recognised malposition of neonatal long lines. Eur J Pediatr. 2005;164:469-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Reece A, Ubhi T, Craig AR, Newell SJ. Positioning long lines: contrast versus plain radiography. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2001;84:F129-F130. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Odd DE, Page B, Battin MR, Harding JE. Does radio-opaque contrast improve radiographic localization of percutaneous central venous lines? Arch Dis Child Neonatal Ed. 2004;89:F41-43. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fioravanti J, Buzzard CJ, Harris JP. Pericardial effusion and tamponade as a result of percutaneous silastic catheter use. Neonatal Netw. 1998;17:39-42. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Beattie PG, Kuschel CA, Harding JE. Pericardial effusion complicating a percutaneous central venous line in a neonate. Acta Paediatr. 1993;82:105-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Aiken G, Porteous L, Tracy M, Richardson V. Cardiac tamponade from a fine silastic central venous catheter in a premature infant. J Paediatr Child Health. 1992;28:325-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nadroo AM, Lin J, Green RS, Magid MS, Holzman IR. Death as a complication of peripherally inserted central catheters in neonates. J Pediatr. 2001;138:599-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Garg M, Chang CC, Merritt RJ. An unusual case presentation: pericardial tamponade complicating central venous catheter. J Perinatol. 1989;9:456-457. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Keeney SE, Richardson CJ. Extravascular extravasation of fluid as a complication of central venous lines in the neonate. J Perinatol. 1995;15:284-288. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Nour S, Puntis JW, Stringer MD. Intra-abdominal extravasation complicating parenteral nutrition in infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1995;72:F207-F208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | De A, Imam A. Long line complication: accidental cannulation of ascending lumbar vein. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005;90:F48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chen CC, Tsao PN, Yau KI. Paraplegia: complication of percutaneous central venous line malposition. Pediatr Neurol. 2001;24:65-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Coit AK, Kamitsuka MD. Peripherally inserted central catheter using the saphenous vein: importance of two-view radiographs to determine the tip location. J Perinatol. 2005;25:674-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rossetti F, Pittiruti M, Lamperti M, Graziano U, Celentano D, Capozzoli G. The intracavitary ECG method for positioning the tip of central venous access devices in pediatric patients: results of an Italian multicenter study. J Vasc Access. 2015;16:137-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Brissaud O, Harper L, Lamireau D, Jouvencel P, Fayon M. Sonography-guided positioning of intravenous long lines in neonates. Eur J Radiol. 2010;74:e18-e21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Berger TM, Stocker M, Caduff J. Neonatal long lines: localisation with conventional radiography using a horizontal beam technique. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2006;91:F311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Butler GC, Al-Assaf N, Tarrant A, Ryan S, El-Khuffash A. Using lateral radiographs to determine umbilical venous catheter tip position in neonates. Ir Med J. 2014;107:256-258. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Hearn RI, Fenton AC. Neonatal percutaneous line tip position on supine radiography isn’t always enough to verify position. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0220113838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Baker J, Imong S. A rare complication of neonatal central venous access. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002;86:F61-F62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cartwright DW. Central venous lines in neonates: a study of 2186 catheters. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89:F504-F508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |