Published online May 10, 2016. doi: 10.5317/wjog.v5.i2.197

Peer-review started: September 18, 2015

First decision: October 30, 2015

Revised: December 8, 2015

Accepted: January 21, 2016

Article in press: January 22, 2016

Published online: May 10, 2016

Processing time: 234 Days and 19.1 Hours

AIM: To review of the efficacy and safety outcomes of different single incision slings (SIS) systems, also in comparison with traditional slings.

METHODS: A literature search was conducted in PubMed/MEDLINE database. The research was restricted to randomized and/or prospective trials and retrospective studies, published after 2006, with at least 20 patients with non-neurogenic stress urinary incontinence (SUI). The studies had to assess efficacy and/or safety of the SIS with a minimum follow-up of 12 mo. All the paper assessing the performance of tension free vaginal tape secur were excluded from this review. The final selection included 19 papers fulfilling the aforementioned criteria. Two authors independently reviewed the selected papers.

RESULTS: Four different SIS systems were analysed: Ajust®, Ophira®, Altis® and MiniArc®. The average objective cure rate was 88%. Overall no statistically significant differences were found between SIS and traditional mid-urethral slings (MUS) in terms of objective cure (all P > 0.005). Only one paper showed a statistically lower success rate in MiniArc®vs Advantage® slings (40% vs 90%) and higher rates of failure in the SIS group. Since there was a great variability in terms of tests performed, it was not possible to compare subjective cure between studies. The vast part of the studies showed no major complications after SIS surgery. We also observed very low reported pain rates in SIS patients. The RCTs on Ajust® and MiniArc®, showed better outcomes in terms of post-operative pain compared to MUS. None of the patients reported long- term pain complains.

CONCLUSION: SIS showed similar efficacy to that of traditional slings but lower short-term pain, complication and failure rates.

Core tip: This review shows an average objective cure rate of 88% in minisling patients and underlines their comparable efficacy with traditional slings. Short term pain, complication and failure rates are lower in the minisling group.

- Citation: Tutolo M, De Ridder D, Van der Aa F. Single incision slings: Are they ready for real life? World J Obstet Gynecol 2016; 5(2): 197-209

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6220/full/v5/i2/197.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5317/wjog.v5.i2.197

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is the involuntary leakage of urine associated with effort on exertion, sneezing or coughing. The estimated prevalence is roughly 30% in women aged > 40 years. The annual incidence increases with age (aged > 65 years, annual incidence rates approximately 9%)[1-3]. Several treatment options for SUI exist, including physical therapy, urethral bulking injections, and surgery.

Surgery traditionally consisted of Burch urethropexy or pubovaginal slings[3]. These procedures were found to give adequate results but were also associated with long recovery time and complications such as frequent post-operative voiding dysfunction[4].

Mid urethral slings (MUS) were developed as a less invasive approach to the treatment of SUI. Since the introduction in 1996 of retropubic tension free vaginal tape (TVT), the use of synthetic MUS has grown to become the most common surgery performed for SUI in women.

These procedures have evolved and multiple types of MUS have been launched on the market, enabling treating physicians to offer different therapeutic options to patients with SUI. The single-incision slings (SIS) are one of the latest innovations for female SUI. They were introduced with the concept of using a shorter tape through a single vaginal incision providing a similar “suburethral hammock” to classical MUS[5].

Their anchoring mechanism (to the obturator membrane or muscle) avoids the passage of trocars through the obturator foramen[6]. SIS represent a minimal invasive innovation for the surgical treatment of SUI. Some studies have already proven their efficacy on the short, medium and long term[5,7-9].

The purpose of this study is to review the evidence for different SIS systems, to compare this relatively new system with traditional MUS and to give the reader an overview on the principal SIS currently available, defining their efficacy and safety. Moreover we aim at giving the physician a tool to simplify the clinical decision-making on the base of the existing literature.

The literature search was conducted on PubMed in June 2015. The search strategy included the following terms: “SUI” AND “mid urethral slings”, AND “SISs” AND “female”.

Our research was restricted to randomized and/or prospective trials and retrospective studies with at least 20 patients with non-neurogenic SUI, published after 2006 in English. To be included in the review the studies had to assess efficacy and/or safety of the SIS and have a minimum follow-up of 12 mo. It is important to underline that all the paper assessing the performance of TVT secur were excluded from this review. The reason is the worldwide withdrawal of this sling from practice in March 2013.

Two independent researchers evaluated the articles with one researcher making the final decision.

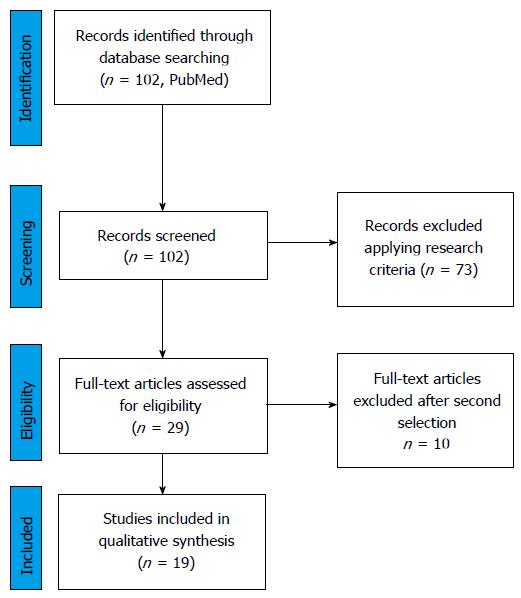

Using the aforementioned research strategy, 102 studies were identified. After applying the eligibility criteria a total of 19 papers were included in the review. Of these, 8 reported efficacy and/or safety outcome on Ajust® (C.R. Bard, Inc., Murray Hill, NJ, United States), 2 on Ophira® (Promedon, Cordoba, Argentina), 2 on Altis® (Coloplast), and 7 on MiniArc® (American Medical System, Inc., Minnesota, United States) (Figure 1). The statistical review of the study was performed by a biomedical statistician.

Method of action/working mechanism: The Ajust® sling provides a strong insertion into the obturator muscle/membrane and allows immediate post insertion adjustment of the tape. A 1 cm incision is made and a bilateral tunnel is created as far as the posterior margin of the inferior pubic ramus. The trocar with the fixed anchor is then introduced and pivoted slowly in the obturator internus and membrane. The adjustable anchor is subsequently placed at the contralateral side and the tape tension is adjusted. A flexible “sylet” is used to lock the adjustable anchor[10].

Population: A total of 8 studies assessing efficacy and/or safety of Ajust® slings have been included in the review[11-18]. All patients included presented with SUI or MUI with predominant stress symptoms. In all the studies, patients with concomitant organ prolapse, predominant overactive bladder symptoms or patients with a history of previous incontinence and/or anterior vaginal wall surgery were excluded. The majority of the studies included do not differentiate the severity of the incontinence. Overall severity information were available for a total of 374 patients who showed moderate to severe SUI[11,15,16].

Evidence efficacy (Table 1): Ajust® sling efficacy was investigated in a total of 3 randomized controlled trials (RCT)[9,11,12].

| Ref. | Design | Participants | Intervention (n) | Comparison | Follow-up | Cure assessment | Cure rate | Assessment of improvement or success | Improv. rate | Success rate | P |

| Schweitzer et al[11] | RCT | 156 | Ajust: 100 | TOT | 12 mo | OC: CST | OC: 90.8% vs 88.6% | - | - | OC: 0.76 | |

| TOT: 56 | SC: UDI-6 | SC: 77.2% vs 72.9% | SC: 0.57 | ||||||||

| Palomba et al[12] | RCT (Multi) | 80 | Ajust: 40 | MiniArc | 24 mo | OC: CST | OC: 47% vs 55% | - | - | P > 0.05 | |

| MiniArc: 40 | SC: % dry? Or improved? | SC: 52.5% vs 65% | P > 0.05 | ||||||||

| Mostafa et al[13] | RCT (Multi) | 137 | Ajust: 69 | TOT | 12 mo | OC: CST | OC: 81.2 vs 82.3% | P = 1 | |||

| TVT-O: 68 | SC: PGI-I | SC: 85.5% vs 84% | P = 1 | ||||||||

| Grigoriadis et al[14] | Prosp matched controlled | 171 | Ajust: 85 | TOT | 22.3 mo (mean) | OC: CTS | OC: 84% vs 86% | - | |||

| TOT: 86 | SC: Patient impression | SC: 81.2% vs 82.6% | |||||||||

| Natale et al[15] | Prosp. (Multi) | 92 | Ajust: 92 | - | 24 mo | OC: CST | OC: 83.7% | - | - | - | |

| SC: PGI-I | SC: 81.5% | ||||||||||

| Naumann et al[16] | Prosp. (Multi) | 51 | Ajust | - | 25.2 ± 2.24 mo (mean) | OC: CTS | 82.4% | Ingelmann-Sundberg scale | 3.9% | 86.3% | - |

| Cornu et al[17] | Prosp. | 95 | Ajust | 21 ± 6 mo (mean) | OC: Pad usage | OC: 80% | - | - | 80% | - | |

| SC: Subjective reports of leakage | SC: 83% | ||||||||||

| Abdel-fattah et al[18] | Prosp. (Multi) | 90 | Ajust | - | 12 mo | - | - | PGI-I | 86% | 80% | - |

| Palma et al[19] | Prosp. (Multi) | 124 | Ophira | 12 mo | OC: 1 h- PWT | OC: 85.3% | Leakage < 50% | 6.30% | |||

| Djehdian et al[20] | RCT | 120 | Ophira: 64 | TOT | 12 mo | OC: CST/ | OC: 68.1% vs 81.9% (ITT) | - | - | - | P = 0.43 and 0.54 |

| TOT: 56 | 20 min pad test | and 73% vs 89% (PP) | |||||||||

| SC: Patient satisfaction | SC: 81.1% vs 88.5% (ITT) and 87.5% vs 96.4% (PP) | P = 0.11 and 0.10 | |||||||||

| Dias et al[21] | Prosp. | 50 | Altis | - | 12 mo | CST | OC: 90.2% | ICIQ-SF lower than pre-op or > 0 | 8% | ||

| ICIQ-SF = 0 | SC: 84% | ||||||||||

| Kocjiancic et al[22] | Prosp. (Multi) | 101 | Altis | - | 12 mo | OC: PWT (< 50% pad weight compared to baseline) | OC: 90% | - | - | - | - |

| and CST | OC: 90.1% | ||||||||||

| SC: PGI-I | SC: 89.3% | ||||||||||

| Lee et al[25] | RCT | 206 | MiniArc: 103 | Monarc | 12 mo | CST (negative) | OC: 94% vs 97% | - | - | - | OC: 0.78 |

| Monarc: 103 | SC: Negative reply to ICIQ 3 and 5 and UI-SF | SC: 92% vs 94% | |||||||||

| SC: 0.50 | |||||||||||

| Schellart et al[26] | RCT | 173 | MiniArc: 86 | Monarc | 12 mo | OC: CST | OC: 89% vs 91% | P = 0.65 | |||

| Monarc: 87 | SC: PGI-I | SC: 83% vs 86% | P = 0.46 | ||||||||

| Basu et al[27] | RCT | 71 | MiniArc: 38 | Advantage | 36 mo | KHQ | 48% vs 90% | All P < 0.05 | |||

| Advantage: 33 | |||||||||||

| Oliveira et al[23,30] | Prosp. | 71 | MiniArc | - | 12 mo | SC: No leakage and no protection | 77% | Use of protection decreased > 50% and affirmative reply to the question: are you satisfied with the results? | 11% | 88% | |

| Deole et al[29] | Prosp. | 59 | MiniArc | 12 mo | OC: CST | OC: 66% | - | - | - | - | |

| SC: ICIQ-SF | SC: median score 6 | ||||||||||

| PGI-I | 64% | ||||||||||

| Presthus et al[24] | Prosp. | 31 | MiniArc | 24 mo | OC: CST and | 93.5% | |||||

| PWT | 90.3% | ||||||||||

| Kennelly et al[31] | Prosp. (Multi) | 142 | MiniArc | 24 mo | OC: CST and | 84.5% | - | - | - | - | |

| PWT | 80.1% | ||||||||||

| SC: UDI-6 | 92.9% |

Two of them compared the efficacy of the adjustable sling system with the classic MUS TOT in a total of 293 patients. At 1-year follow-up, both studies demonstrated no difference between groups in terms of objective cure (assessed with cough stress test - CTS): 90.8% vs 88.6%[11] and 81.2% vs 82.3%[9] in Ajust® and TOT respectively, all P > 0.05. Subjective cure was also assessed. In the paper by Schweitzer et al[11], subjective cure was defined as a negative answer to the UDI-6 question: “do you still experience any leakage related to physical activities?”. In the paper by Mostafa et al[9], it was assessed using the patient global impression of improvement (PGI-I) questionnaire. Using the aforementioned criteria, neither RCT showed any difference in subjective cure rate between the two groups. Failure was defined as any surgical re-treatment for urinary incontinence. Schweitzer et al[11] showed a failure rate of 2.2% and 2% in Ajust® and TOT slings at 1-year. Mostafa et al[13] showed a 7.2% and 4.4% failure rate in Ajust® and TOT respectively. These differences between groups were not statistically significant in both papers[9,11].

The third RCT is a comparison between three SISs, namely TVT Secur®, MiniArc® and Ajust®[12]. As mentioned before, we did not include the results concerning TVT Secur. The other two arms (namely MiniArc® and Ajust®) did not show any difference in terms of subjective and objective cure rates at 6, 12, 18 and 24 mo follow-up. It is important to underline that both objective and subjective cure rates decreased significantly in each arm between 6 and 24 mo. At 24 mo, no difference was found between groups in total failure rates: 60% in the Ajust® group and 55% in MiniArc® group.

In the matched paired study performed by Grigoriadis et al[14] on 171 patients diagnosed with urodynamic SUI, we observed similar results in terms of objective and subjective cure rates at 22 mo follow-up for both thr Ajust® and TOT group. Failure rate varied between 8.1% and 10.6%[14].

We also collected data of 4 prospective studies assessing the efficacy of Ajust® slings up to 1-year follow-up. The results were comparable with those of the RCTs: Objective cure varied from 82.4% to 83.7%. Patient reported cure varied from 80% to 83%[15-18]. However, it has to be underlined that each study used different objective and subjective parameters to assess continence after surgery. Failure of the procedure defined as persisting SUI or need of other types of incontinence surgery vary widely from 0.0% to 14%.

Evidence safety (complications and pain) (Table 2): No major complications were observed in all the studies analysed. In a cohort study, Cornu et al[17] described a post-operative vaginal bleeding managed surgically 8 h after the initial surgery. Also a total of 2 mesh erosions (on 95 patients) requiring surgery were observed after a mean follow-up of 21 mo[17].

| Ref. | Design | Participants | Intervention | Comparison | Timing | Assessment | Pain rate/complications | P |

| Schweitzer et al[11] | RCT | 156 | Ajust: 100 | TOT | Immediatepost-op and up to week 6 | VAS | Median score week 1: | < 6 d: 0.01 |

| TOT: 56 | Ajust: 0.2 | |||||||

| TOT: 1.0 | ||||||||

| Median score week 2: | > 6 d: > 0.05 | |||||||

| Ajust: 0.0 | ||||||||

| TOT: 0.5 | ||||||||

| Palomba et al[12] | RCT (Multi) | 80 | Ajust: 40 | MiniArc | 24 mo follow-up | VAS | Pain score Ajust: | All P > 0.05 |

| MiniArc: 40 | 5.3 ± 3.8 | |||||||

| Pain score MiniArc: | ||||||||

| 5.0 ± 3.5 | ||||||||

| Complications: | ||||||||

| Ajust: 17.5% | ||||||||

| MiniArc: 5% | ||||||||

| 1 mesh erosion in Ajust group (no surgical revision) | ||||||||

| Grigoriadis et al[14] | Prosp. matched controlled | 171 | Ajust: 85 | TOT | Post-op and during follow-up | Patient’s impression | 3.5% vs 5.8% | - |

| TOT: 86 | ||||||||

| Natale et al[15] | Prosp. (Multi) | 92 | Ajust n = 92 | - | Post-op and during follow-up | Patient’s impression | 1 leg pain, 3 mesh extrusion (of which 1 mesh removal) | - |

| Naumann et al[16] | Prosp. (Multi) | 51 | Ajust | - | 1 d after surgery and at during follow-up | VAS | 1 patient day 1 | - |

| Cornu et al[17] | Prosp. | 95 | Ajust | 1-6 and 12 mo and yearly thereafter | Use of pain medication and surgeon’s and patient’s reports | 1 vaginal bleeding managed surgically 8 h after surgery. | - | |

| At last follow-up 2 patients still complained of tight and vaginal pain respectively | ||||||||

| Abdel-fattah et al[18] | Prosp. (Multi) | 90 | Ajust | - | Intra-op., after 30 min and 3 h pot-surgery or at the time of discharge | 10 point Likert scale | 1 case had to be converted in standard MUS (kit fault). Median pain rate at the time of the discharge was 0 and didn’t change during follow-up | - |

| Palma et al[19] | Prosp. (Multi) | 124 | Ophira | TOT | 1-yr and 2 yr | Patient’s impression | 1 patient severe intraoperative painà sedation. 2 mesh resection: 1.6% | P > 0.05 |

| Djehdian et al[20] | RCT | 120 | TOT: 56 | Day 1 and after 4-6 wk | VAS | 0% vs 1.7% | P = 0.04 | |

| Ophira: 64 | ||||||||

| Dias et al[21] | Prosp. | 50 | Altis | - | 12 mo | Patient’s report | 1 mesh erosion treated surgically (2%) | |

| Kocjiancic et al[22] | Prosp. (Multi) | 101 | Altis | - | During 12 mo follow-up | Patient’s and surgeon’s reports | Non-pelvic pain: 9 (8%) | |

| 3 serious adverse events (1 bleeding, 2 mesh extrusion requiring surgery) | ||||||||

| Lee et al[25] | RCT | 206 | MiniArc: 103 | Monarc | 24 h after surgery and 12 mo follow-up | Patient’s and surgeon’s reports | Women requiring analgesia: 0.5 vs 2 tablets) and groin pain | P = 0.02 |

| Monarc: 103 | 9.7% vs 33% | P < 0.01 | ||||||

| 1 mesh erosion in the MiniArc group at 1 yr follow-up | ||||||||

| Schellart et al[26] | RCT | 173 | MiniArc: 86 | Monarc | 3 d and 4 wk | VAS | 2 vs 3 | P = 0.90 |

| Monarc: 87 | Use of pain medications | 8% vs 3% | P = 0.37 | |||||

| Basu et al[27] | RCT | 71 | MiniArc: 38 | Advantage | During follow-up | Patient’s response on late adverse events | No late adverse events | - |

| Advantage: 33 | ||||||||

| Oliveira et al[23,30] | Prosp. | 71 | MiniArc | - | First 24 h | VAS | 1.0 ± 1.4 | - |

| (one patient had pain for 6 mo) | ||||||||

| Deole et al[29] | Prosp. | 59 | MiniArc | - | Intra and post-op | Surgeon’s and patient’s reports and Wong-Baker score | No major intraoperative complications | - |

| Wong-Baker score: 2 ± 1.5 | ||||||||

| Presthus et al[24] | Prosp. | 31 | MiniArc | - | Intra and post-op | Surgeon’s and patient reports and Wong baker faces | No major intraoperative complications | - |

| Pain rate 9.6% | ||||||||

| Kennelly et al[31] | Prosp. (Multi) | 142 | MiniArc | - | At discharge and at 7 d post-op | Surgeon’s and patient’s reports and Wong-Baker score | No major complications | - |

| Median pain score 0 |

In the RCT comparing Ajust® and MiniArc® the number of patients using analgesic tablets during the first 30 d from surgery (P = 0.349) and the number of analgesic tablets used (P = 0.124) were similar among both groups.

Complications occurred in 7 (17.5%) and 2 (5.0%), cases from the Ajust® and MiniArc® groups respectively. All post-operative complications were Dindo grade 1, and they were not significantly different among the groups (P = 0.897).

Schweitzer et al[11] showed a significantly lower pain score in the Ajust® group vs the TOT group during the first week. However no differences were found after day 6 between both groups (P = 0.75).

OAB symptoms: In the RCT by Shweitzer only women with moderate to severe SUI were included. Seven out of 100 women in the Ajust® group and four out of 56 in the TOT group reported new onset of OAB. Both the RCT by Mostafa et al[13] and Palomba et al[12] included also patients with mixed urinary incontinence. In the first paper the authors showed a trend toward higher rates of de novo urgency and/or worsening of the pre existing urgency in the Ajust® group during the first 4 mo (although it was found not to be statistically significant) but this finding was not retained at 1-year. Moreover there was no significant difference between the two groups (6.5% vs 8.7% in TOT vs Ajust®, P = 0.74)[12].

De novo or worsened urgency UI was noted in 5 patients, in the paper by Palma et al[19], occurring in 3/40 (7.5%) and 2/40 (5.0%) cases in the Ajust® and MiniArc® groups, respectively[16].

In the study by Grigoriadis et al[14], there was a total of 10/85 (11.6%) vs 8/86 (9.4%) patients that complained of early post-operative symptoms of frequency and urgency in the TOT group vs Ajust® groups respectively (P < 0.05). No DO was demonstrated on urodynamic investigation[14].

In the prospective study by Mostafa et al[13], the authors assessed post-operative urgency in a group of pure SUI and mixed incontinence patients, using the urgency perception scale (UPS). Pre operative assessment of urgency showed 53/90 patients (59%) to have urgency symptoms. Of them, 35/53 (66%) reported post-operative improvement of urgency (29 of them reported total cure). However, 18/53 (20%) patients reported no improvement or even worsening of the symptoms. No data on de novo urgency was described by the authors[18].

Cornu et al[17] also showed a decreasing trend in OAB symptoms after surgery compared to the pre-operative assessment (35% vs 25%). Of them 12/95 (12.6%) had de novo urgency and 12/95 (12.6%) reported persistent OAB symptoms[17].

Natale et al[15] reported a rate of post-operative urgency of 5.4% (5/92), 9.8% (9/92) of which de novo urgency. In the group of patient with pre-operative OAB symptoms (n = 36, 39.1%), 27 reported persistence of urgency and of them 18 had a good response to pharmacotherapy (30%)[15].

Naumann et al[16] reported on 6/51 patient (12%), having a preoperative patient perception of intensity of urgency scale higher than 1 (i.e., at least moderate urgency). However, 3 of them (60%) reported improvement of urgency compared to their situation before surgery and 2 (40%), reported severe urgency (2/5: 4%)[16].

Method of action/working mechanism: Ophira®, has blue loosening sutures inserted in the base of both fixation arms, giving the ability to correct tension during the procedure. The fixation system has multiple fixation points along its self-fixating arms.

The system includes a “Retractable Insertion Guide” to improve control and ease when inserting the sling and releasing it in the correct position. The connectors located at the ends enable the Retractable Insertion Guide to be inserted easily and safely.

The delivery trocar is inserted in the small vaginal incision and guided by the surgeon toward the obturator internus. When half of the mesh is within the incision, the deployment button on the needle is pressed and the sling is kept in place by the self-anchoring fishbone columns.

Population: A total of two studies on Ophira® slings have been included in the review. One study is a prospective cohort study (n = 124) that includes women older than 18 years with a urodynamically confirmed diagnosis of SUI in absence of neurological disease[19]. The second one is a RCT including also women (n = 120) older than 18 years but with positive CST, urine leakage greater than 2 g (measured by a standardized pad test with 250 mL bladder volume) and urodynamic stress incontinence[20].

Evidence efficacy (Table 1): In the prospective cohort study by Palma et al[19] 124 women were included in the study to assess efficacy, safety and predictors of failure of Ophira® slings. The authors compared also the results at 1 and 2 years after surgery. Objective cure at 24 mo was 85.3% and improvement 6.3%. Overall 8.4% patient had failure and the only predictor of failure was previous incontinence surgery (P = 0.04)[19].

In the randomized prospective trial by Djehdian et al[20] comparing Ophira® and TOT, the efficacy at 12 mo was analysed using a non-inferiority test. They demonstrated no differences in terms of objective and subjective cure rates between the two slings in both intention to treat and per protocol analyses (all P > 0.5).

Overall failure rate was 19%. In the Ophira® group 5/64 patients (7.8%) did not achieve an objective and subjective cure, and were submitted to a second surgery. In TOT group, 1/56 (1.8%) of patients were submitted to a second surgery for failure. However no statistically significant differences have been found between groups[20].

Evidence safety (complications and pain) (Table 2): No major complications were reported in both studies. In the prospective randomized paper there was no difference in terms of complications between the two groups. However the number of patients complaining of tight pain resulted to be significantly higher in the TOT group compared to the Ophira® group (7.1% vs 0% respectively; P = 0.04). Two patients in the Ophira® group had the tape cut for voiding obstruction[20].

OAB symptoms: In the prospective cohort study, de novo urgency was reported in 9/124 patients (7.3%)[19]. In the prospective randomized study comparing Ophira® slings with TOT, symptoms of urgency were determined by patient’s self reported response to urogenital distress inventory short form 1 and 2. The authors reported a significant reduction of in urge symptoms in both surgeries; Ophira®: 35.9% vs 3.1% and TOT 15.7% vs 3.5% (all P < 0.01) but no statistically significant difference was found between groups[20].

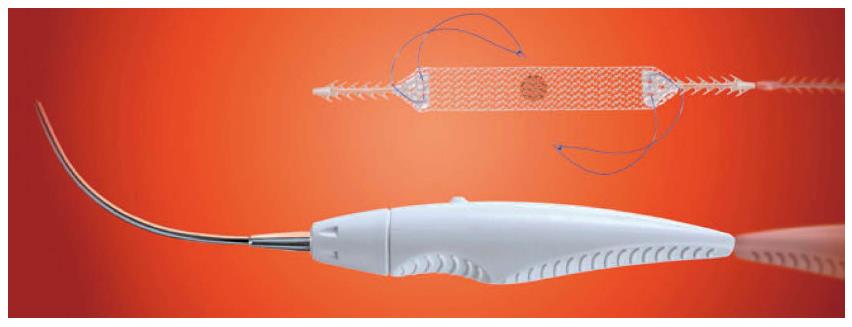

Method of action/working mechanism: The Altis® SIS is a low elasticity sling. The dynamic adjustability of the sling allows for accurate tensioning and placement of the sling in relation to the urethra. Its low elasticity and adjustability allows tensioning, placement and positioning of the sling under the urethra without compression.

The introducers are curved in shape and come as a set for the inside-out approach. They are designed for holding the anchor on the tip until insertion into the obturator membrane complex.

A monofilament suture is attached to the sling body and extends over the sides of the sling. The suture is connected to a dynamic anchor, which allows tensioning of the sling after placement. Positioning of the sling should be without tension to the urethra as the Altis® sling has a low 7.5% elasticity.

The surgical procedure is similar to the others single incision approaches. Using the introducer, the static anchor is placed through the obturator membrane. The dynamic anchor is then placed on the other side to be sure not to have tension. The suture extending from the sling and through the dynamic anchor is designed for two-way adjustability (metti Erwin). In all the studies included, a CST was performed to adequately tension the sling. The dynamic anchors holding force and suture design prevents sling movement during the tissue in-growth period. This also eliminates the need for a locking mechanism. Following the procedure, the excess suture is cut and discarded.

Population: In the prospective observational study by Dias et al[21], a total of 50 women completed the 1-year follow-up and were included in the analysis. All women had SUI or MUI (mixed urinary incontinence) with predominant stress component, a positive cough test and a previous failure of conservative treatments[21]. The same inclusion criteria were used in the prospective multicentre study of Kocjancic et al[22] (n = 101) where they demonstrated pre-operative incontinence also with urodynamic exam.

Evidence efficacy (Table 1): In the small observational prospective study by Dias et al[21] the patient’s reported subjective cure is 84% at 12 mo with an additional 8% of reported improvement. The objective cure, assessed with a standard CST is 92%. Failure was defined as the indication for mesh removal or absence of cure or improvement. Overall failure rate was 8%[21].

In the prospective study of Kocjancic et al[22] the overall objective cure tested with 24 PWT was 90% and CST was negative in 90.1% of patients. PGI-I was 89.3%. At 12 mo, 1 patient reported no changes compared to baseline and 2 patients reported the situation to be a little bit worse. Overall 2.9% of patients were not satisfied with the results[22].

Evidence safety (complications and pain) (Table 2): Dias et al[21] demonstrated no major complications in their observational study. The authors report none of the patients to require significant analgesics (only oral ibuprofen and/or acetaminophen in the first few days were used), however we have no clear data on pain because of the lack of validated scale in this study[21].

Kocjancic et al[22] registered three serious adverse events: One included a pelvic hematoma after revision surgery for urinary obstruction, the second one was a mesh extrusion categorized as a serious adverse event because the patient withdrew the study before revision surgery. The third event was a mesh extrusion for which the sling was trimmed on two separate surgeries. No cases of persistent pelvic pain were reported[22].

OAB symptoms: Just one of the included studies on Altis® sling analysed also the new onset of OAB symptoms. Dias et al[21] reported de novo urge incontinence rate to be 5.9% (3/50 patients).

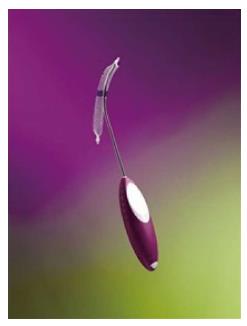

Method of action/working mechanism: One of the most widely used and studied SIS is the MiniArc®. It has been used to treat female SUI since 2007, when the original MiniArc® Single-Incision Sling System was introduced.

As the others, this is a minimally invasive procedure using a small (1.5 cm) vaginal incision and a sharp dissection to the inferior pubic ramus in order to create the trajectory for the needle. The tip of the needle is keyed to the sling extremity so that the mesh lay on the convexity of the needle. The sling is advanced through the trajectories created with the scissors bilaterally and its self anchoring tip pushed along the posterior surface of the of the ischio-pubic ramus, taking care not to perforate the obturator membrane[23].

Population: A total of 7 studies analysing efficacy and/or safety of MiniArc® slings were included in the review[23-29]. A total of 753 patients had a follow-up ≥ 12 mo. All studies included women with SUI or mixed incontinence with predominant complains of stress. Only in one study women with mixed incontinence were excluded and only women with documented pure SUI were included[23]. Women with a story of previous incontinence surgery, previous sling operation, concomitant pelvic prolapse ≥ 2, neurogenic bladder, or predominant urodynamic detrusor overactivity, were excluded from the analysis in the majority of the studies.

Evidence efficacy (Table 1): Our selection of papers on MiniArc®[25-27] slings includes two randomized clinical trials comparing MiniArc® and Monarc slings and one comparing MiniArc® and Advantage sling. In the RCT by Lee et al[25] 103 patients in each group reached 1-year follow-up. There was no statistically significant difference in terms of subjective and objective cure rates between groups. Failure rate was 2.7% vs 1.8% in the MiniArc® group and in the Monarc group respectively; P = 0.68)[25].

In the RCT by Schellart et al[26], comparing MiniArc® and Monarc women, subjective cure was similar between both groups. The objective cure rate, defined as negative CST during follow-up, was also not statistically different between groups. Overall a total of 4 failures requiring a second surgery for SUI were identified: 3 in the Monarc group and 1 in the MiniArc® group[26].

Basu et al[27] in 2013 published the three-years results from their randomized trial comparing Advantage™ slings and MiniArc®™. They reported a success rate of 48% for MiniArc®™ with a failure rate of 52% (combining subjective failures with the need for repeat continence surgery). Moreover the MiniArc® were associated with a higher rate of persistent SUI (34% vs 9%)[27].

Overall 5 prospective studies on MiniArc® slings were included in the review[23,24,28,29]. Oliveira et al[23,30] reported 12 mo follow-up of patients with pure SUI. The intention to treat analysis showed a subjective cure rate of 80% and an improvement of 11%. The same group updated the analysis at 45 mo and showed 70 patients of the 77 responders to maintain the initial improvement/cure rate (91%).

All the other cases were reported as failures (7% in patients with 1-year follow-up)[23,30].

Deole et al[29] showed lower rates of objective and subjective cure at 1-year compared to other studies (66% and 64% respectively). They did demonstrate a statistically significant difference in post-operative subjective cure rates (defined as mean ICIQ-SF scores) compared to pre-operative scores (mean 8.6% ± 6.6% vs 16% ± 3.7% respectively, P < 0.001). Failure was reported in a total of 3/59 patients (5%) of which 1 was lost at follow-up but included in the analysis as failure. The other 2 patients reported persistent obstructive symptoms (requiring transection) and erosion of the mesh respectively[29].

In the prospective cohort study by Presthus et al[24] the objective cure ranged between 90% and 93% at 24 mo. Moreover patients reported a statistically significant improvement in UDI-6 and IIQ-7 compared to baseline. The percentage of patients with improvement in UDI-6 and IIQ-7 scores was 90.3% and 100% respectively. Failure rate was 9.6% (a total of 3 patients at 24 mo)[24].

Kennelly et al[28,31] in 2012 reported objective and subjective cure to be 84.5% and 93% respectively. Moreover a significant improvement occurred in UDI-6 and IIQ-7 compared to baseline. In their first paper of 2010, a total of 4 patients were reported to have surgical failures within the first year of follow-up. However no additional cases of surgical failure or adverse events have been reported from 12 to 24 mo[28,31].

Evidence safety (complications and pain) (Table 2): No major complications were reported in all the studies assessing MiniArc® safety. Lee et al[25] reported a statistically significant higher rate medication use and groin pain in Monarc group (all P < 0.05). Schellart et al[26] demonstrated a statistically significant difference pain score in the first 3 d after surgery in favour of MiniArc® patients.

No late side effects, pain or complications were registered by Basu et al[27], at 3-year follow-up[25-27].

Overall low pain scores were registered also in the prospective studies included in this review. Only one patient reported groin pain for more than 6 mo after MiniArc® implant. Pain rates were generally very low either using VAS or patient reported impressions during the entire follow-up[23,24,28,29].

OAB symptoms: In the RCT by Lee et al[25] there was no difference in terms of post-operative OAB symptoms between the two groups at 1-year follow-up (median ICIQ OAB scores: 3 vs 3 in MiniArc® and monarc respectively; P = 0.48). However a difference was registered in terms of use of anticolinergic medications (5.5% vs 15.8% in MiniArc® and Monarc respectively; P = 0.034)[25]. On the other end Schellart et al[26] did not show any difference in terms of UDI-6 domain score for irritative symptoms between the two groups at 1-year follow-up.

Oliveira et al[30] showed a new onset of OAB symptoms in a total of 7 patients (6%). However the symptoms were classified as mild to moderate and solved spontaneously or were well controlled with anticholinergics. Deole et al[29] reported a 24% of de novo urgency symptoms of which 9% required anticholinergics at 3 mo follow-up. De novo urgency incontinence rate was reported to be 10% at 24 mo by Kennelly et al[31]. Presthus et al[24] reported only one patient to have de novo urge incontinence after surgery (3.2%) and of 10 patients witheline OAB symptoms, 90% reported no more symptoms at 24 mo.

The European Association of Urology Guidelines, concerning the treatment of female SUI, report that MUS, inserted by either the transobturator or retropubic route, give equivalent patient-reported outcome at 12 mo[7].

SIS represent the last modification to the MUS for SUI. They require very limited dissection and might further increase safety of sub-urethral slings. Many options have been proposed on the market but despite the increasing interest in SIS and their widespread use, there are still conflicting results on their effectiveness and safety.

Many recent reviews and meta-analysis on effectiveness and complications of SIS vs standard MUS have shown better outcomes for SIS in terms of operating time, better recovery and less intraoperative bleeding[5,13,32]. However there is still a lack of standardized characteristics for the ideal candidate for minisling surgery. There exist several different types of SIS systems with different characteristics that show different outcomes. The results of a particular SIS system cannot be transposed to another. In this review we report efficacy and safety of SIS and their effect on OAB symptoms, in patient with more than one year follow-up. We didn’t focus our research on the advantages of SIS in terms of operating time or intraoperative bleeding already extensively assessed in previous reviews.

In our review we analysed different SIS systems, namely: Ajust®, Ophira®, Altis® and MiniArc®. Given that 63% of the studies included in the review are prospective or retrospective studies (level of evidence 3) we have to conclude that the evidence for SIS remains quite weak[7].

Nevertheless 2 randomized studies including 293 patients and comparing Ajust® sling with traditional TOT sling demonstrated high objective and subjective cure rates (ranging between 81% and 91% for objective cure and between 77% and 85% for subjective cure) and no difference between groups. Failure rate ranged between 2.2% and 7.2% but no difference was found between groups[9,11].

A third randomized study including Ajust® and MiniArc® slings showed no differences between the two slings in objective and subjective cure on the short term (OC: 80% vs 82.5% and SC: 90% vs 92.5%). However, a statistically significant difference was found when comparing the results at 6 mo with the results at 24 mo (OC: 47% vs 55% and SC: 52.5% vs 65%) in Ajust® and MiniArc® respectively, with lower rates of objective and subjective cure compared to the short term follow-up and other studies[12]. This decline, in OC and SC rates, has not been demonstrated in other studies by several other groups. The reason for this inferior resulted in this particular study is not clear.

Data from prospective studies analysing the efficacy of Ajust® sling on a total of 328 patients showed an objective cure rate between 80% and 84% and a subjective cure between 81% and 83%. However there was a variability between studies in terms of failure rates (range 0.02% and 14%).

In the RCT study comparing Ophira® slings and TOT, no difference was found in objective and subjective cure either in intention to treat analysis and per protocol analysis[20]. Palma et al[19] in their prospective study on Ophira®, showed higher rates of objective cure with a 6.3% improvement at 2 years but also higher rates of failure compared to the RCT (8.4% vs 7.8% respectively).

We found no RCT assessing the efficacy of the Altis® sling. Two prospective cohort studies on 151 patients with 12-mo follow-up did show similar results in terms of objective cure compared to the other RCTs (90.2% and 90%)[15,21,22].

One of the most widely used SIS is the MiniArc® sling. Our review includes a total of 3 RCT comparing MiniArc® to traditional MUS (namely Monarc and Advantage) including data on 450 women. The objective cure assessed with standard CST in the studies by Lee and Schellart was respectively 94% and 92% in MiniArc® slings and no difference was found between groups in both alayses. In this case, the MiniArc® sling was not inferior to monarc with respect to both objective and subjective cure. Failure was 1.8% and 0.5 % in Lee and Schellart paper respectively.

Basu et al[27] recently published the three years results of their RCT comparing MiniArc® to advantage sling. They reported a success rate of 48% in MiniArc® slings and a failure rate of 52% (combining subjective failures with the need of repeat continence surgery). Moreover the MiniArc® slings were associated with a higher rate of persistent SUI.

Oliveira et al[30] described a success rate for MiniArc® slings of 88%, analysing only patients completing the 1 year follow-up visits. Failure rate however was higher compared to the two RCT (7%). The other prospective studies included in the paper showed results in line with the aforementioned RCT: The objective cure varied between 77% and 93%. Failures rates ranged between 3% and 7%. It is to underline that Deole et al[29] showed lower rates of cure compared to the other authors but a statistically significant difference compared to baseline.

We would like to underline that objective cure rates have been assessed using the standard cough stress test with 200 mL in the bladder in the majority of the studies, so it was possible to compare the different studies in terms of objective cure with an average objective cure rate of 88%.

It was not possible to compare subjective cure between studies since there was a great variability in terms of test performed (the majority of them were patient reported improvement or impression).

The vast part of the included studies did not show any major complication for minisling surgery. However Cornu et al[17] reported 1 post-operative vaginal bleeding requiring surgery and Kocjancic a serious pelvic hematoma and a mesh extrusion causing the abandoning of the study before second surgery and Dias showed 1 mesh erosion requiring surgery in the Altis® group. Two mesh erosions requiring surgery were registered also in the Ajust® group. In the Ophira® group two patients had the mesh cut for post-operative voiding obstruction.

Pain rate is another parameter difficult to compare because of the lack of standardized questionnaires or examinations. The majority of data obtained on pain were assessed by patient reports or VAS scale (also a subjective scale). However we can observe very low reported pain rates.

None of the patients reported persistent pelvic pain at long term follow-up. Both RCTs on Ajust® and MiniArc®, showed better outcomes in terms of immediate post-operative pain compared to traditional slings[25,26].

Again due to variability in the used parameters, it was not possible to systematically assess the new onset of OAB or worsening of the pre-existing OAB symptoms in all patients. It is of notice that all studies except 1 included also women with pre-existing mixed symptoms.

Some studies showed a trend toward higher rates of de novo urgency or worsening of pre-existing symptoms in the first months after surgery. We can assess that an average rate of 10% of de novo OAB symptoms or worsening of the pre-existing incontinence were reported in the minisling studies. On the other hand, Mostafa, Cornu and Djehdian showed a decrease in post-operative urgency in patients with baseline OAB symptoms. Moreover Presthus et al[24] demonstrated a 90% improvement in OAB symptoms after MiniArc® slings in patients with pre-operative urgency.

This review shows an average objective cure rate of 88% in minisling patients and underlines their comparable efficacy with traditional slings. Short-term pain, complication and failure rates are lower in the minisling group. In general we showed good results of minislings on the short and medium follow-up compared to traditional MUS. However this result supports the need of long-term follow-up, prospective, randomized trials, with adequate numbers and validated questionnaires to identify the best candidate for this type of procedure.

Single incision slings (SIS) represent a minimal invasive treatment for stress urinary incontinence (SUI). Some SIS have proven their efficacy on the short, medium and long-term follow in comparative studies with traditional mid urethral slings (MUS). The final purpose of this study is to guide the physician into the correct management of incontinent patient in order to give them a correct counselling in terms of surgical treatment of SUI.

MUS were developed as a less invasive approach to the treatment of SUI. Nowadays the use of synthetic MUS is the most common surgery performed for SUI in women. The SIS are one of the latest innovations for female SUI. Their anchoring mechanism avoids the passage of trocars through the obturator foramen. Some studies have already proven their efficacy on the short, medium and long term.

The purpose of this study is to review the evidence for different SIS systems and to compare them with traditional MUS. The authors give an overview on the principal SIS currently available, defining their efficacy and safety.

This review can give the physician a tool to simplify the clinical decision-making on the base of the existing literature.

SUI: Stress urinary incontinence; MUS: Midurethral slings; SIS: Single incision slings; TOT: Trans obturator tape; TVT: Tension free vaginal tape; RCT: Randomized controlled trial; OC: Objective cure; SC: Subjective cure; OAB: Overactive bladder; UPS: Urgency perception scale; PGI-I: Patient Global Impression of Improvement; CST: Cough stress test; PWT: Pad weight test; ITT: Intention to treat; PP: Per protocol; ICIQ-SF: International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire - Short Form; UI-SF: Urinary incontinence-Short form; UDI-6: Urogenital Distress Inventory.

This is a nice review.

P- Reviewer: Nowicki S, Soria F S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK

| 1. | Imamura M, Abrams P, Bain C, Buckley B, Cardozo L, Cody J, Cook J, Eustice S, Glazener C, Grant A. Systematic review and economic modelling of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of non-surgical treatments for women with stress urinary incontinence. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14:1-188, iii-iv. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Abrams P, Andersson KE, Birder L, Brubaker L, Cardozo L, Chapple C, Cottenden A, Davila W, de Ridder D, Dmochowski R. Fourth International Consultation on Incontinence Recommendations of the International Scientific Committee: Evaluation and treatment of urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and fecal incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29:213-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 744] [Cited by in RCA: 733] [Article Influence: 48.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Schimpf MO, Rahn DD, Wheeler TL, Patel M, White AB, Orejuela FJ, El-Nashar SA, Margulies RU, Gleason JL, Aschkenazi SO. Sling surgery for stress urinary incontinence in women: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:71.e1-71.e27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Leach GE, Dmochowski RR, Appell RA, Blaivas JG, Hadley HR, Luber KM, Mostwin JL, O’Donnell PD, Roehrborn CG. Female Stress Urinary Incontinence Clinical Guidelines Panel summary report on surgical management of female stress urinary incontinence. The American Urological Association. J Urol. 1997;158:875-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 485] [Cited by in RCA: 487] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Abdel-Fattah M, Ford JA, Lim CP, Madhuvrata P. Single-incision mini-slings versus standard midurethral slings in surgical management of female stress urinary incontinence: a meta-analysis of effectiveness and complications. Eur Urol. 2011;60:468-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cox A, Herschorn S, Lee L. Surgical management of female SUI: is there a gold standard? Nat Rev Urol. 2013;10:78-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lucas MG, Bosch RJ, Burkhard FC, Cruz F, Madden TB, Nambiar AK, Neisius A, de Ridder DJ, Tubaro A, Turner WH. EAU guidelines on surgical treatment of urinary incontinence. Eur Urol. 2012;62:1118-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Oliveira R, Silva C, Dinis P, Cruz F. Suburethral single incision slings in the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence: what is the evidence for using them in 2010? Arch Esp Urol. 2011;64:339-346. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Mostafa A, Agur W, Abdel-All M, Guerrero K, Lim C, Allam M, Yousef M, N’Dow J, Abdel-fattah M. A multicentre prospective randomised study of single-incision mini-sling (Ajust®) versus tension-free vaginal tape-obturator (TVT-O™) in the management of female stress urinary incontinence: pain profile and short-term outcomes. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;165:115-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Abdel-fattah M, Mostafa A, Young D, Ramsay I. Evaluation of transobturator tension-free vaginal tapes in the management of women with mixed urinary incontinence: one-year outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:150.e1-150.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Schweitzer KJ, Milani AL, van Eijndhoven HW, Gietelink DA, Hallensleben E, Cromheecke GJ, van der Vaart CH. Postoperative pain after adjustable single-incision or transobturator sling for incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:27-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Palomba S, Falbo A, Oppedisano R, Torella M, Materazzo C, Maiorana A, Tolino A, Mastrantonio P, La Sala GB, Alio L. A randomized controlled trial comparing three single-incision minislings for stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:1333-1341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mostafa A, Agur W, Abdel-All M, Guerrero K, Lim C, Allam M, Yousef M, N’Dow J, Abdel-Fattah M. Multicenter prospective randomized study of single-incision mini-sling vs tension-free vaginal tape-obturator in management of female stress urinary incontinence: a minimum of 1-year follow-up. Urology. 2013;82:552-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Grigoriadis C, Bakas P, Derpapas A, Creatsa M, Liapis A. Tension-free vaginal tape obturator versus Ajust adjustable single incision sling procedure in women with urodynamic stress urinary incontinence. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;170:563-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Natale F, Dati S, La Penna C, Rombolà P, Cappello S, Piccione E. Single incision sling (Ajust™) for the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence: 2-year follow-up. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;182:48-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Naumann G, Hagemeier T, Zachmann S, Al-Ani A, Albrich S, Skala C, Laterza R, Linaberry M, Koelbl H. Long-term outcomes of the Ajust Adjustable Single-Incision Sling for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:231-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cornu JN, Peyrat L, Skurnik A, Ciofu C, Lucente VR, Haab F. Ajust single incision transobturator sling procedure for stress urinary incontinence: results after 1-year follow-up. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:1265-1270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Abdel-Fattah M, Agur W, Abdel-All M, Guerrero K, Allam M, Mackintosh A, Mostafa A, Yousef M. Prospective multi-centre study of adjustable single-incision mini-sling (Ajust(®) ) in the management of stress urinary incontinence in women: 1-year follow-up study. BJU Int. 2012;109:880-886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Palma P, Riccetto C, Bronzatto E, Castro R, Altuna S. What is the best indication for single-incision Ophira Mini Sling? Insights from a 2-year follow-up international multicentric study. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:637-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Djehdian LM, Araujo MP, Takano CC, Del-Roy CA, Sartori MG, Girão MJ, Castro RA. Transobturator sling compared with single-incision mini-sling for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:553-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dias J, Xambre L, Costa L, Costa P, Ferraz L. Short-term outcomes of Altis single-incision sling procedure for stress urinary incontinence: a prospective single-center study. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:1089-1095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kocjancic E, Tu LM, Erickson T, Gheiler E, Van Drie D. The safety and efficacy of a new adjustable single incision sling for female stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2014;192:1477-1482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Oliveira R, Botelho F, Silva P, Resende A, Silva C, Dinis P, Cruz F. Single-incision sling system as primary treatment of female stress urinary incontinence: prospective 12 months data from a single institution. BJU Int. 2011;108:1616-1621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Presthus JB, Van Drie D, Graham C. MiniArc single-incision sling in the office setting. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19:331-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lee JK, Rosamilia A, Dwyer PL, Lim YN, Muller R. Randomized trial of a single incision versus an outside-in transobturator midurethral sling in women with stress urinary incontinence: 12 month results. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:35.e1-35.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Schellart RP, Oude Rengerink K, Van der Aa F, Lucot JP, Kimpe B, de Ridder DJ, Dijkgraaf MG, Roovers JP. A randomized comparison of a single-incision midurethral sling and a transobturator midurethral sling in women with stress urinary incontinence: results of 12-mo follow-up. Eur Urol. 2014;66:1179-1185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Basu M, Duckett J. Three-year results from a randomised trial of a retropubic mid-urethral sling versus the Miniarc single incision sling for stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:2059-2064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kennelly MJ, Moore R, Nguyen JN, Lukban J, Siegel S. Miniarc single-incision sling for treatment of stress urinary incontinence: 2-year clinical outcomes. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:1285-1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Deole N, Kaufmann A, Arunkalaivanan A. Evaluation of safety and efficacy of single-incision mid-urethral short tape procedure (MiniArc™ tape) for stress urinary incontinence under local anaesthesia. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:335-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Oliveira R, Resende A, Silva C, Dinis P, Cruz F. Mini-arc for the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence: long-term prospective evaluation by patient reported outcomes. ISRN Urol. 2014;2014:659383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kennelly MJ, Moore R, Nguyen JN, Lukban JC, Siegel S. Prospective evaluation of a single incision sling for stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2010;184:604-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Mostafa A, Lim CP, Hopper L, Madhuvrata P, Abdel-Fattah M. Single-incision mini-slings versus standard midurethral slings in surgical management of female stress urinary incontinence: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of effectiveness and complications. Eur Urol. 2014;65:402-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |