Published online May 10, 2013. doi: 10.5317/wjog.v2.i2.34

Revised: April 22, 2013

Accepted: May 8, 2013

Published online: May 10, 2013

Processing time: 95 Days and 22.1 Hours

Caput succedaneum is relatively common at birth but infrequently diagnosed in utero. We report the first case of a prenatal incarcerated caput succedaneum after cervical cerclage in a patient with premature rupture of the membranes (PPROM). A 41-year-old woman was referred and admitted to our hospital due to PPROM at 19 wk of gestation. Aggressive therapy, including amnioinfusion, cervical cerclage, and administration of antibiotics and tocolysis, was initiated. At 24 wk of gestation, a thumb tip-sized and polyp-like mass, which was irreducible, was delineated with a vaginal examination, vaginal speculum, and transvaginal ultrasonography, leading to the diagnosis of incarcerated caput succedaneum. Under general anesthesia, the incarcerated caput succedaneum was repositioned with fingers after cutting the string to avoid necrosis, and then, placement of a McDonald cervical cerclage was undertaken again. At 26 wk of gestation, she delivered a 678 g girl through an emergency cesarean section performed due to profuse bleeding and prolonged decelerations. A slight bulge with hair was observed on the head by palpation at birth. Cephalic ultrasonography, X-ray, magnetic resonance imaging and electroencephalogram confirmed no abnormality. Although the baby needed oxygen (0.2 L/min) at the time of hospital discharge, she has grown favorably at three years of corrected age.

Core tip: Caput succedaneum is relatively common at birth but infrequently diagnosed in utero. Furthermore, no case of incarceration of antenatal caput succedaneum has been reported in the literature. This is the first report of prenatal and incarcerated caput succedaneum after cervical cerclage in a patient with premature rupture of the membranes (PPROM). The presenting case makes obstetricians recognize that cerclage placement, especially in a patient with PPROM, may result in unusual caput succedaneum in utero. When it develops to incarceration, earlier release should be considered to prevent the serious complication of necrosis.

- Citation: Okazaki A, Miyazaki K, Kihira K, Furuhashi M. Prenatal incarceration of caput succedaneum: A case report. World J Obstet Gynecol 2013; 2(2): 34-36

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6220/full/v2/i2/34.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5317/wjog.v2.i2.34

Caput succedaneum is a cranial subcutaneous serohematic extravasation that can be differentiated from cephalhematoma by findings of extension over a suture line and definite palpable edges. It is more likely to form during a prolonged or difficult delivery and often resolves in several d without sequelae. Furthermore, it is relatively common at birth but infrequently diagnosed in utero[1-4]. We present a case of caput succedaneum that was diagnosed by ultrasonographic examination during the antepartum period.

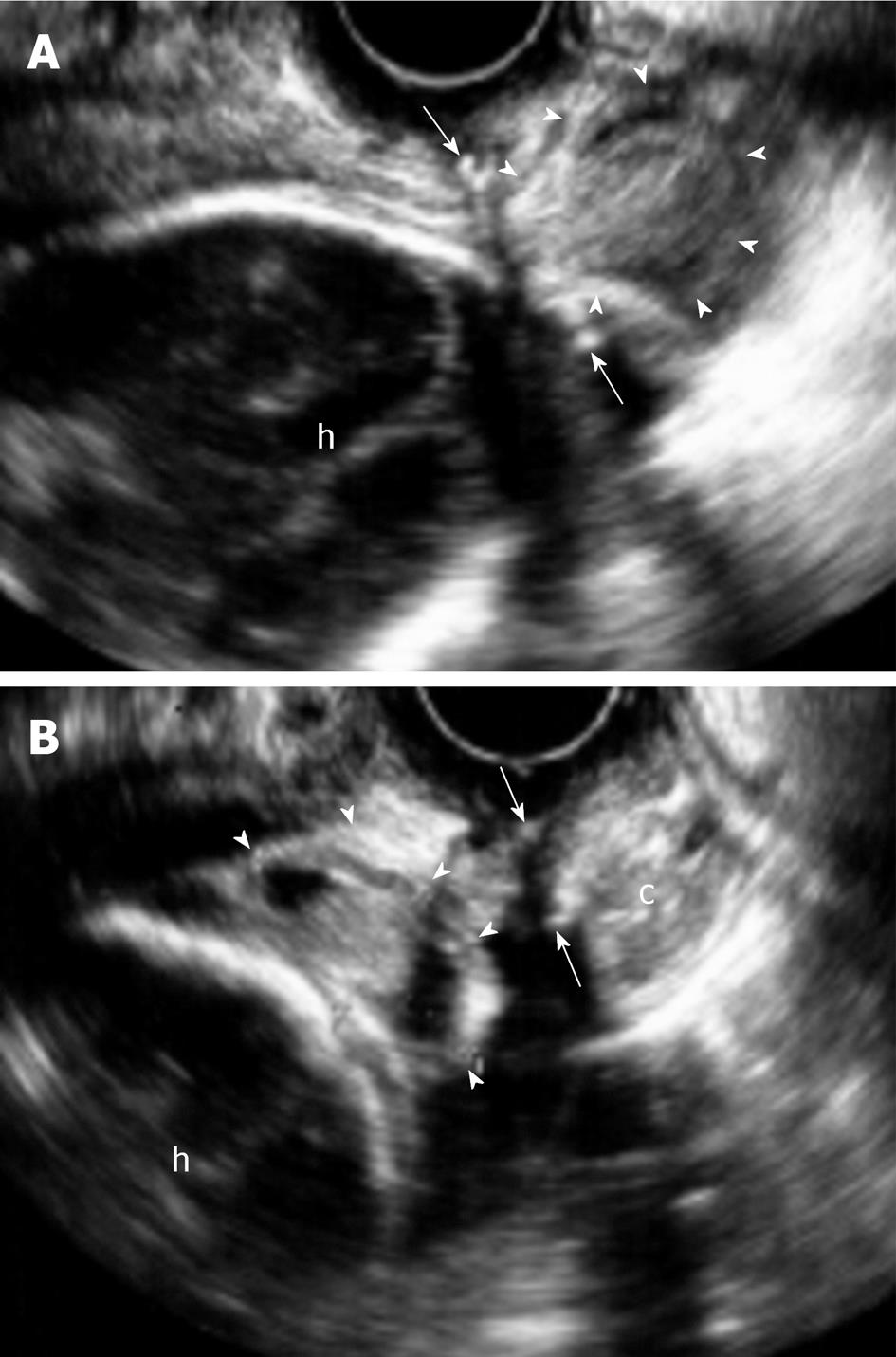

A 41-year-old woman, gravida 3, para 0, was referred and admitted to our hospital due to patient with premature rupture of the membranes (PPROM) at 19 wk and 6 d of gestation. Her surgical history was unremarkable, except for conization of the cervix at age 37 for carcinoma in situ. She had been on insulin therapy due to diabetes mellitus. On admission, she was afebrile. The plasma level of C-reactive protein (CRP) and white blood cell count were 0.1 mg/dL and 9500/mm3, respectively. These findings showed that there was no clinical chorioamnionitis. Vaginal examination demonstrated 2 cm-dilated cervical os and amniotic fluid flowing out. Laboratory culture of the vaginal discharge was negative. She reported a history of intermittent staining since the first trimester of pregnancy. Ultrasound showed that the cervical length was 28 mm, and the maximum cord-free amniotic pocket was 2.5 cm. Although we informed her that she might have a bad prognosis, she wanted to continue the pregnancy. A catheter was transabdominally indwelled in the amniotic cavity after introduction of a 21-gauge needle under continuous ultrasound guidance. Although the amniotic culture was negative, the amniotic fluid polymorphonuclear neutrophil leukocyte, glucose, lactate dehydrogenase, and neutrophil elastase levels were 371 cells/mm3, 20 mg/dL, 2575 IU/L, and 14.7 μg/mL, respectively, showing intra-amniotic inflammation[5]. She underwent placement of a McDonald cervical cerclage using polyester tape under intravenous anesthesia to prevent cervical dilation. Subsequently, amnioinfusion was initiated, whose purpose was not retention of the fluid but lavage throuth perfusion. Approximately 1000 mL/d sterile and warm saline was spontaneously drip- infused into the amniotic cavity, and the corresponding volume of fluid flowed out every day. Magnesium sulfate and ritodrine were used for tocolysis. Antibiotic therapy was also given. Cefmetazole sodium (2 g/d iv), piperacillin sodium (4 g/d iv), anhydrous ceftriaxone sodium (2 g/d iv), and meropenem trihydrate (1 g/d iv) were administered in sequential order until delivery. The level of blood CRP and white blood cell was in the normal range. At 23 wk and 3 d of gestation, a small amount of outflow was unexpectedly observed, although a certain level of amniotic fluid was observed in utero by ultrasonography. The latter finding suggested obstruction of the cervical canal. Thus, saline inflow was kept at the level of outflow to prevent hydramnios. At 24 wk and 0 d of gestation, a thumb tip-sized and polyp-like mass, which was irreducible, was delineated with a vaginal examination. A vaginal speculum demonstrated a purple-black-colored mass with hair on the surface. These findings along with transvaginal ultrasonography (Figure 1A) led to the diagnosis of caput succedaneum. Because the most feared sequela was necrosis, we decided that the incarceration should be released. Under general anesthesia, the incarcerated caput succedaneum was repositioned with fingers after cutting the string, and then, placement of a McDonald cervical cerclage was undertaken again. The same treatment strategy as before was taken to allow the fetus to become mature enough to survive. At 25 wk and 0 d of gestation, transvaginal ultrasonography showed an echogenic bulge within the soft tissue of the fetal head (Figure 1B). The estimated fetal weight was 598 g, corresponding to the weight for 23 wk and 3 d. At 26 wk and 1 d of gestation, profuse bleeding occurred, and prolonged decelerations were observed on fetal heart rate monitoring. Thus, an emergency cesarean section was performed, and she delivered a 678 g girl with an Apgar score of 1 (5-min). There was a true knot of the umbilical cord. Placental pathology demonstrated histologic chorioamnionitis (Grade 3) and funisitis (Grade 2). The arterial blood gas analyses of the umbilical cord showed that the pH and base deficit were 7.04 and 17.9 mmol/L, respectively. Resuscitation was started without delay. The levels of CRP and immunoglobulin M were 5 μg/dL and 9 mg/dL, respectively. Arterial blood culture was negative. The head of the newborn baby looked normal with hair by inspection, but a slight bulge was observed by palpation at birth. Cephalic ultrasonography, X-ray, and magnetic resonance imaging confirmed no abnormality, such as an intracranial hemorrhage, a skull fracture, or a bone defect. She had a normal electroencephalogram at 1 and 40 wk after birth. The newborn central hearing screening showed no abnormality. Meanwhile, she was affected with retinopathy of prematurity and received laser coagulation. She has grown favorably without alopecia and shows normal physical and neurological development at three years of corrected age.

The common management in most centers of PPROM before 22 wk of gestation is termination of the pregnancy or the expectant approach because expectant management results in an increased rate of fetal and neonatal morbidity and mortality[6,7]. When a patient with previable PPROM desires continuation of the pregnancy, more aggressive interventions, such as amnioinfusion[8], cervical cerclage, and intra-amniotic gelatin sponge[9], are not infrequently required in addition to the administration of antibiotics and tocolysis to prolong pregnancy until the fetus becomes viable. In such cases, our usual protocol is to supply continuous amnioinfusion, cervical cerclage, and the use of antibiotics and tocolysis after obtaining informed consent[10]. The aggressive intervention of previable PPROM results in a high neonatal survival rate[10].

Caput succedaneum is a cranial subcutaneous serohematic extravasation that is more likely to form during a prolonged or difficult delivery and often resolves in several d without sequelae. Although it has been infrequently diagnosed in utero[1-4], no case of incarceration has been reported in the literature. It would appear that several factors are associated with incarceration of caput succedaneum. Uterine contractions are primarily inevitable, as usual caput succedaneum is formed during delivery. In addition, PPROM might play a pivotal role because pressure is directly placed on the fetal scalp contiguous to the internal os of the uterus in the setting of oligohydramnios. This assumption is supported by the fact that a percentage of cephalhematoma and caput succedaneum in utero is involved in PPROM[2-4]. Cerclage placement is also a contributing factor. Even a successful cerclage may result in limited dilation of the cervix when uterine contractions are persistent because they may promote cervical maturation and diminish its thickness. In that event, the opening encircled by the suture might induce prolapse of the caput succedaneum and form an incarceration when it swells. Considering that only a slight bulge of the newborn head was observed at birth in our case, caput succedaneum in utero could spontaneously reduce but for incarceration.

One of the serious sequelae of perinatal scalp injury is halo scalp ring, which is annular scalp alopecia. Although it is usually a temporary defect, a necrotic caput succedaneum may result in scarring alopecia because deep ulceration can destroy hair follicles[11,12]. This concept suggests that incarceration of caput succedaneum is harmful to the fetus. Because it is not difficult to diagnose prenatal incarceration of caput succedaneum through vaginal examination and ultrasonography, special attention should be paid to prevent undesirable necrosis.

In conclusion, obstetricians should recognize that cerclage placement, especially in a patient with PPROM, may result in unusual caput succedaneum in utero. When it develops to incarceration, earlier release should be considered to prevent the serious complication of necrosis.

P- Reviewers Inês Rosa M, Khajehei M, Li JX S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Sherer DM, Allen TA, Ghezzi F, Gonçalves LF. Enhanced transvaginal sonographic depiction of caput succedaneum prior to labor. J Ultrasound Med. 1994;13:1005-1008. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Petrikovsky BM, Schneider E, Smith-Levitin M, Gross B. Cephalhematoma and caput succedaneum: do they always occur in labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:906-908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bats AS, Senat MV, Mohlo M, Ville Y. [Discovery of caput succedaneum after premature rupture of the membranes at 28 weeks gestation]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2003;32:179-182. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Gerscovich EO, McGahan JP, Jain KA, Gillen MA. Caput succedaneum mimicking a cephalocele. J Clin Ultrasound. 2003;31:98-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kidokoro K, Furuhashi M, Kuno N, Ishikawa K. Amniotic fluid neutrophil elastase and lactate dehydrogenase: association with histologic chorioamnionitis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:669-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dewan H, Morris JM. A systematic review of pregnancy outcome following preterm premature rupture of membranes at a previable gestational age. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;41:389-394. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Dinsmoor MJ, Bachman R, Haney EI, Goldstein M, Mackendrick W. Outcomes after expectant management of extremely preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:183-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Locatelli A, Vergani P, Di Pirro G, Doria V, Biffi A, Ghidini A. Role of amnioinfusion in the management of premature rupture of the membranes at <26 weeks’ gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:878-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | O’Brien JM, Barton JR, Milligan DA. An aggressive interventional protocol for early midtrimester premature rupture of the membranes using gelatin sponge for cervical plugging. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:1143-1146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Miyazaki K, Furuhashi M, Yoshida K, Ishikawa K. Aggressive intervention of previable preterm premature rupture of membranes. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91:923-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tanzi EL, Hornung RL, Silverberg NB. Halo scalp ring: a case series and review of the literature. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:188-190. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Siegel DH, Holland K, Phillips RJ, Drolet BA, Esterly NB, Frieden IJ. Erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp after perinatal scalp injury. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:533-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |