Published online May 18, 2016. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v7.i5.338

Peer-review started: February 14, 2016

First decision: March 1, 2016

Revised: March 10, 2016

Accepted: March 24, 2016

Article in press: March 25, 2016

Published online: May 18, 2016

Gluteal compartment syndrome (GCS) is a rare condition. We present a case of gluteal muscle strain with hematoma formation, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) superinfection, leading to acute GCS, rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury. This combination of diagnoses has not been reported in the literature. A 36-year-old Caucasian male presented with buttock pain, swelling and fever after lifting weights. Gluteal compartment pressure was markedly elevated compared with the contralateral side. Investigations revealed elevated white blood cell, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, creatine kinase, creatinine and lactic acid. Urinalysis was consistent with myoglobinuria. Magnetic resonance imaging showed increased T2 signal in the gluteus maximus and a central hematoma. Cultures taken from the emergency debridement and fasciotomy revealed MRSA. He had repeat, debridement 2 d later, and delayed primary closure 3 d after. GCS is rare and must be suspected when patients present with pain and swelling after an inciting event. They are easily diagnosed with compartment pressure monitoring. The treatment of gluteal abscess and compartment syndrome is the same and involves rapid surgical debridement.

Core tip: Gluteal compartment syndrome (GCS) is rare. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infected GCS with rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury has not been reported. Compartment pressure monitoring and magnetic resonance imaging are useful for the diagnosis of this condition. Successful management comprises surgical fasciotomy, debridement together with antibiotics.

- Citation: Woon CYL, Patel KR, Goldberg BA. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infected gluteal compartment syndrome with rhabdomyolysis in a bodybuilder. World J Orthop 2016; 7(5): 338-342

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v7/i5/338.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v7.i5.338

Gluteal compartment syndrome (GCS) is a rare condition. It may present after prolonged immobilization[1] or after surgical procedures[2-4]. In this report, we present a case of gluteal muscle strain with hematoma formation, secondary bacterial superinfection by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), leading to elevated compartment pressures, resulting in acute GCS. This led to rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury. This combination of diagnoses has not previously been reported in the literature.

A 36-year-old healthcare professional presented with increasing right buttock pain, swelling and stiffness for two days. Six days prior, he performed stiff-leg deadlifts with 295lbs, and 2 d prior, he performed seated cable rows with 240lbs. This was an increase from his normal routine. After the cable rows, he developed increasing right buttock pain and swelling and a limp. He had no fever, chills or paresthesias and denied a history of penetrating trauma, use of intramuscular anabolic agents or personal or family history of bleeding diathesis. His past medical history was significant for acute disseminated encephalomyelitis at 24-25 years of age, treated with steroids and intravenous immunoglobulins for 6 mo. Because of this, he had persistent diminished sensation from the T6 dermatome distally. There were no previous episodes of sepsis following dentistry or innocuous trauma.

At the emergency department, he had 40.4 °C fever, pulse rate was 124 bpm, respiratory rate was 22 bpm, blood pressure was 131/60 mmHg. Examination revealed warm, erythematous, tender, hard swelling of the right buttock. The left buttock was normal. Right hip motion was limited by pain, with flexion to 45°, abduction to 30°, and internal and external rotation in flexion to 30°. Lower extremity sensibility was symmetrical and unchanged from before. Ankle dorsi- and plantar flexion strength was 5/5 bilaterally. Distal pulses were symmetric. Of note, he demonstrated gross hematuria at the bedside.

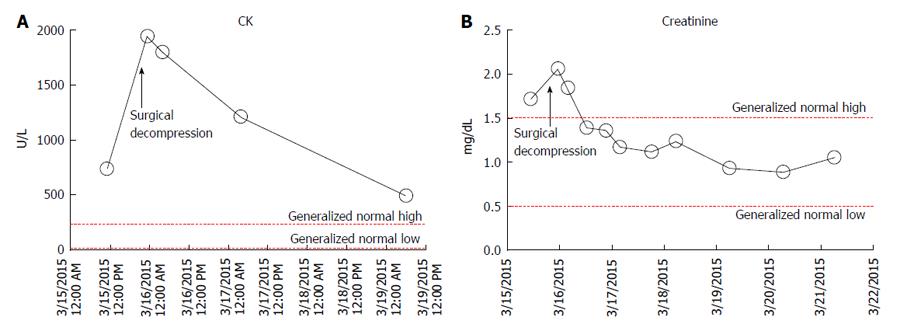

Laboratory tests revealed white blood cell count 20300/μL (normal, 3.9-12.0), 88.9% neutrophils, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 31 mm/h (normal: 0-10) and C-reactive protein 17.7 mg/dL (normal: 0.0-0.8). Creatine kinase (CK) was 740/μL (normal: 21-232, Figure 1A), and potassium was 5.0 mmol/L (normal: 3.5-5.3), ionized calcium was 3.1 mg/dL (normal: 4.2-5.4), phosphate was 2.3 mg/dL (normal: 3.0-4.5) and blood urea nitrogen/creatinine ratio was 11.6 (normal: 12-20), suggestive of rhabdomyolysis. Lactic acid was 2.3 mEq/L (normal: 0.5-2.2), creatinine was 1.72 mg/dL (normal: 0.5-1.5, Figure 1B). Urinalysis revealed moderate blood on macroscopic exam, but only 3 red blood cells/high-power field on microscopic exam, consistent with myoglobinuria.

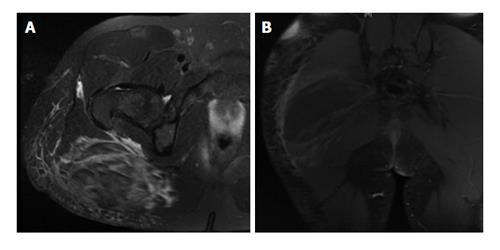

Radiographs were unremarkable. Magnetic resonance imaging showed gluteus maximus swelling and increased T2 signal, consistent with a high-grade muscle strain, and a central 13 cm × 5 cm area of non-enhancement, suggestive of a hematoma (Figure 2). There was no hip joint effusion. A single dose of vancomycin and ceftriaxone was administered in the emergency room. Gluteal compartment pressures measured with the Stryker intra-compartmental pressure monitor (Stryker Surgical, Kalamazoo, MI) revealed compartment pressures of 58 mmHg and 4 mmHg for the right and left sides, respectively.

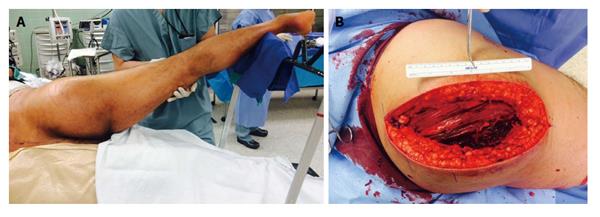

In the operating room, the gluteus maximus compartment was released using a Kocher-Langenbeck incision. Gross purulence was noted (Figure 3). Fascia over the tensor fascia lata (TFL) and gluteus medius was released and these 2 compartments were found to be uninvolved. The wound was irrigated and packed with wet-to-dry dressings. He was transferred to the intensive care unit for hydration and monitoring of renal function and serial CK (Figure 2). Intraoperative cultures revealed MRSA. Blood cultures were negative. Nasal cultures were negative for MRSA. He was started on vancomycin, cefepime and metronidazole after intraoperative cultures and adjusted to clindamycin based on final sensitivities.

He underwent repeat exploration, irrigation and debridement 2 d later. Necrotic, non-contractile gluteal muscle and cloudy interstitial fluid was noted. A necklace of antibiotic beads (Cobalt PMMA cement, Biomet, Warsaw, IN and 4 g of vancomycin powder) was placed and the wound was dressed with Ioban (3M, St Paul, MN). He underwent a third exploration 3 d later. The wound was clean and delayed primary closure was performed.

He was discharged the following day and seen in the office 10 d later. The incision had healed with no recurrence. He was discharged from further follow-up.

This patient had a unique combination of: (1) unilateral GCS; (2) MRSA infection of a hematoma; and (3) rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury following weightlifting. Possible explanations include: (1) Acute muscle strain with expanding hematoma and bacterial superinfection, leading to elevated intracompartmental pressures; (2) Acute exertional compartment syndrome from acute muscle hypertrophy, causing GCS and late bacterial superinfection; (3) MRSA pyomyositis leading to GCS, and muscle ischemia; (4) Valsalva-related arteriole rupture, leading to an expanding hematoma, elevated intracompartmental pressures and muscle ischemia, and subsequent bacterial superinfection; and (5) Surreptitious intramuscular injection of anabolic agents (which he vehemently denies), community-acquired MRSA superinfection, late compartment syndrome and muscle necrosis. All these hypotheses share a final common pathway of elevated compartment pressures, muscle necrosis and rhabdomyolytic kidney injury.

The temporal relationship of events leads us to believe that the first scenario is the most likely. Acute exertional compartment syndrome is unlikely as he would have presented within hours of exertion with overwhelming signs of compartment syndrome.

This combination of findings has not been reported in the literature. GCS occurs most commonly following immobilization[1,5] because of diminished consciousness related to alcohol or illicit drugs[6], or prolonged surgery, e.g., knee arthroplasty[2], hip arthroplasty[3], abdominal aortic aneurysm repair[7], and bariatric surgery[8]. Less common causes include falls and blunt trauma[9], intramuscular injections[10], and aerobic exercise[11].

Infected GCS can occur in tropical pyomyositis[12]. Staphylococcus aureus is responsible for > 75% of cases and the quadriceps, iliopsoas and gluteal muscles are most commonly affected. In these cases, it is believed that exercise elevates intracompartmental pressure with subsequent bacterial seeding[12]. Infected GCS can also occur with Group A Streptococcus pyogenes (GAS) infection. This usually occurs in immunocompetent individuals and mortality is lower than expected (15%) with other GAS infections because of earlier detection and debridement[13].

Iatrogenic bacterial seeding causing GCS can occur after intramuscular injection[10] or acupuncture. The risk is increased in anticoagulated patients, patients with bleeding diathesis, immunocompromised patients, and those with diabetes mellitus.

Acute exertional rhabdomyolysis, acute renal failure, and myoglobinuria after GCS, usually involves multiple other limb compartments[11]. Here, exercise-induced dehydration leads to rhabdomyolysis, while subsequent aggressive fluid resuscitation leads to limb swelling[11].

The diagnosis of GCS was made with needle manometry. David et al[14] described the entry points for manometry in the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius-minimus, and the TFL compartments[5]. Most authors advocate using either absolute compartment pressures > 30 mmHg or delta P < 30 mmHg as thresholds for surgical decompression.

The Kocher-Langenbeck incision provides excellent access to all 3 compartments and preserves femoral head vascularity[14]. Should greater exposure be required, Henry’s “question mark” incision and medial reflection of the gluteus maximus as a “gluteal lid” is a feasible alternative[15]. Buttock soft tissue is pliable, well vascularized and mobile. Delayed primary closure is usually possible. Closure by secondary intention or skin grafting is almost never necessary. Rapid resolution of CK (Figure 1) after fasciotomy is an indicator of successful decompression[11].

This patient presented with right buttock pain and swelling after working out.

Examination revealed tender, hard swelling of the right buttock.

Differential diagnoses includes compartment syndrome, myositis, cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis, abscess, septic arthritis, deep vein thrombosis.

Elevated serum white blood cell count with left shift, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, elevated creatine kinase, potassium, creatinine and lactic acid.

Magnetic resonance imaging showed gluteus maximus swelling and hematoma.

Compartment pressures monitoring revealed elevated gluteal compartment pressures.

Urgent surgical debridement, fasciotomy and intravenous antibiotics.

Gluteal compartment syndrome (GCS) is rare but presents with similar physical findings as compartment syndromes of the leg, thigh and upper extremity. If constitutional signs and signs of local sepsis are present, suspect infected compartment syndrome.

With methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) superinfection of GCS urgent debridement is necessary to prevent systemic septicemia and tissue necrosis.

The manuscript on the management of the gluteal compartment syndrome due to MRSA infection and abscess is interesting, well-written and does have educational value to both practicing and trainee surgeons.

P- Reviewer: Friedman EA, Shrestha BM, Watanabe T S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Mustafa NM, Hyun A, Kumar JS, Yekkirala L. Gluteal compartment syndrome: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:190. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Osteen KD, Haque SH. Bilateral gluteal compartment syndrome following right total knee revision: a case report. Ochsner J. 2012;12:141-144. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Kumar V, Saeed K, Panagopoulos A, Parker PJ. Gluteal compartment syndrome following joint arthroplasty under epidural anaesthesia: a report of 4 cases. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2007;15:113-117. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Pai VS. Compartment syndrome of the buttock following a total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11:609-610. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Taylor BC, Dimitris C, Tancevski A, Tran JL. Gluteal compartment syndrome and superior gluteal artery injury as a result of simple hip dislocation: a case report. Iowa Orthop J. 2011;31:181-186. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Liu HL, Wong DS. Gluteal compartment syndrome after prolonged immobilisation. Asian J Surg. 2009;32:123-126. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chew MH, Xu GG, Ho PW, Lee CW. Gluteal compartment syndrome following abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: a case report. Ann Vasc Surg. 2009;23:535.e15-535.e20. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Bostanjian D, Anthone GJ, Hamoui N, Crookes PF. Rhabdomyolysis of gluteal muscles leading to renal failure: a potentially fatal complication of surgery in the morbidly obese. Obes Surg. 2003;13:302-305. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 96] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Brumback RJ. Traumatic rupture of the superior gluteal artery, without fracture of the pelvis, causing compartment syndrome of the buttock. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:134-137. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Kühle JW, Swoboda B. [Gluteal compartment syndrome after intramuscular gluteal injection]. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1999;137:366-367. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kuklo TR, Tis JE, Moores LK, Schaefer RA. Fatal rhabdomyolysis with bilateral gluteal, thigh, and leg compartment syndrome after the Army Physical Fitness Test. A case report. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:112-116. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Lamdan R, Silverstein E, Feder HM, MacGilpin D. Tropical pyomyositis of the hip short external rotators associated with elevated intra compartmental pressure. Orthopedics. 2008;31:398. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kleshinski J, Bittar S, Wahlquist M, Ebraheim N, Duggan JM. Review of compartment syndrome due to group A streptococcal infection. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336:265-269. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | David V, Thambiah J, Kagda FH, Kumar VP. Bilateral gluteal compartment syndrome. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:2541-2545. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Henry A. Exposures in the Lower Limb. Extensile Exposure. 2nd ed: Churchill Livingstone 1973; 180-190. [Cited in This Article: ] |