Published online May 18, 2016. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v7.i5.293

Peer-review started: October 18, 2015

First decision: January 4, 2016

Revised: February 16, 2016

Accepted: March 7, 2016

Article in press: March 9, 2016

Published online: May 18, 2016

Soft tissue sarcoma accounts for approximately 1% of all cancers diagnosed annually in the United States. When these rare malignant mesodermal tumours arise in the pelvis and extremities, they may potentially encase or invade large calibre vascular structures. This presents a major challenge in terms of safe excision while also leaving acceptable surgical margins. In recent times, the trend has been towards limb salvage with vascular reconstruction in preference to amputation. Newer orthopaedic and vascular reconstructive techniques including both synthetic and autogenous graft reconstruction have made complex limb-salvage surgery feasible. Despite this, limb-salvage surgery with concomitant vascular reconstruction remains associated with higher rates of post-operative complications including infection and amputation. In this review we describe the initial presentation and investigation of patients presenting with soft tissue sarcomas in the pelvis and extremities, which involve vascular structures. We further discuss the key surgical reconstructive principles and techniques available for the management of these complex tumours, drawn from our institution’s experience as a national tertiary referral sarcoma service.

Core tip: This paper describes the investigation and management of patients presenting with a complex soft tissue pelvic and extremity sarcomas that also compromise local vascular structures. The principles of surgical management of these cases are described in light of the most recent evidence, with examples drawn from our experience to illustrate these principles. We emphasize the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in the care of this complex patient cohort.

- Citation: McGoldrick NP, Butler JS, Lavelle M, Sheehan S, Dudeney S, O'Toole GC. Resection and reconstruction of pelvic and extremity soft tissue sarcomas with major vascular involvement: Current concepts. World J Orthop 2016; 7(5): 293-300

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v7/i5/293.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v7.i5.293

Soft tissue sarcomas are rare malignant tumours that are invariably fatal if not treated aggressively. Surgical excision of these lesions offers the only hope of potential cure. Sarcomas located in the pelvis and extremities may potentially encase or invade large caliber vascular structures. This presents the orthopaedic surgeon with a major challenge in balancing safe excision while still maintaining acceptable surgical margins. Moreover, involvement of major vascular structures was historically assumed to carry grave prognosis, since it was thought the vessels would provide a route of haematogenous spread of the tumour[1]. It was for this reason that early, more conservative attempts at limb preservation surgery, which frequently left inadequate margins, invariably resulted in unacceptably high rates of local recurrence.

The philosophical turning point in the management of these complex cases came with a report by Fortner et al[2] describing the earliest initial series of en bloc resection of tumour with involved vascular structures. Although preservation of the limb was achieved, high rates of post-operative oedema were observed in patients where no vascular reconstruction was performed. Improved rates of oedema and function were observed in the subsequent three patients who underwent concomitant arterial reconstruction at the time of tumour resection by the same author.

Unsurprisingly given the nature and relative rarity of these aggressive tumours, no large randomized control trials investigating optimal treatment strategies have been reported in the literature. Issues surrounding the role of venous reconstruction, the choice of autologous vs synthetic graft, and appropriate anticoagulation have meant controversy remains concerning optimal treatment of this complex patient cohort. Despite this, technical advances in the fields of both orthopaedic and vascular surgery have resulted in a trend towards aggressive limb salvage with vascular reconstruction in preference to amputation. The addition of both pre- and post-operative radiotherapy and chemotherapy has resulted in a truly multimodal treatment strategy for these complex cases.

The primary focus of this review will be to discuss the broad principles concerning the appropriate investigation and treatment of these complex tumours, with illustrative cases drawn from our institution’s experience as a national tertiary referral center for sarcoma in Ireland. Particular attention will be paid to the strategy for management of the vascular component of these difficult resections.

Soft tissue sarcomas represent a heterogenous group of rare malignant tumours of mesenchymal origin with an estimated 9000 new cases diagnosed each year in the United States[3]. Currently, more than 50 histological subtypes of soft tissue sarcoma have been characterized. More than half (59%) of these tumours are found in the extremities, although they may be found anywhere in the body[4]. Despite improved treatment strategies, the overall survival rate for all stages of soft tissue sarcoma remains relatively disappointing at a level between 50% and 60%[4]. Reports in the literature suggest involvement of adjacent blood vessels in approximately 5% of cases, although Schwarzbach et al[5] report an incidence of 10%[5,6].

Clinical examination of the patient on initial presentation will often elicit the possibility of vascular involvement of a sarcomatous lesion. Reduced or absent palpable arterial pulsation distal to the level of a mass should raise concern in the clinician’s mind about vascular compromise.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has now become the gold standard of work-up for soft tissue sarcoma and should be performed to evaluate any suspicious lesions. However, colour duplex sonography, computed tomography (CT) and formal angiography have all been reported modalities used in the diagnosis of a soft tissue sarcoma invading vascular structures[5,7-9]. The addition of radiographic contrast to the study helps delineate vascular structures. The location of the mass, its depth in relation to fascia, heterogeneity and signal characteristics should be determined. More specifically, the relationship of the lesion to adjacent blood vessels, and other important structures, must carefully be considered. Vascular involvement may be diagnosed when MRI or CT demonstrates absence of normal tissue in the tumour-to-vessel plane[5]. MRI and magnetic resonance imaging angiography (MRA) can be useful in guiding the surgeon as to the length of vessel that is likely to be resected, as well as identifying potential donor vessels for reconstruction. Pre-operatively, lower limb venous duplex and vein marking of the contralateral limb may also be useful to map patent vein graft available for harvest at the time of resection.

All of these factors should be weighed-up by the operating surgeon in planning any proposed attempt at surgical resection. Involvement of a vascular surgeon at this point, where there exists the possibility of major vessel reconstruction, is crucial.

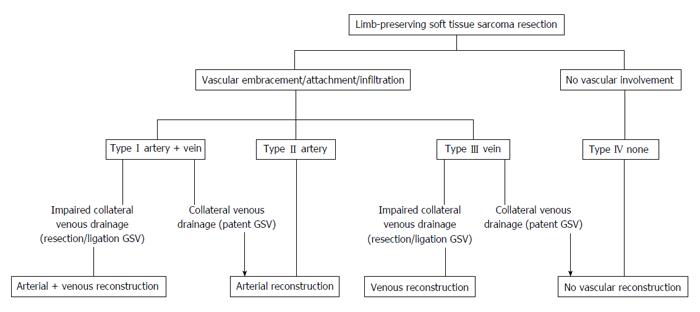

Schwarzbach et al[5] have classified the pattern of vascular involvement, which may be useful in guiding surgical management (Figure 1). Type I soft tissue sarcomas involve both major arteries and veins, while Type II lesions involve the artery in isolation. Type III lesions were characterized as those with purely venous involvement, leaving an intact artery. Type IV lesions have no involvement of either artery or vein, and require no vascular reconstruction.

In cases of type I involvement, Schwarzbach et al[5] propose both arterial and venous reconstruction where there is impaired collateral venous drainage. In type I cases with adequate venous drainage, arterial reconstruction alone may be sufficient.

In type II cases, the artery may be resected, and reconstructed using either venous autograft or alternatively prosthetic material, depending on surgeon preference and available autogenous graft. Some authors have advocated the use of isolated limb perfusion in these cases[10,11]. The rationale for this is to isolate the limb from circulation to facilitate direct administration of high dose cytotoxic agents, with the aim of down-staging the tumour, and ultimately preserving the native vascular structures. The role of this modality of treatment, however, remains controversial.

In type III cases, venous reconstruction has been advocated where there is impaired venous drainage. If sufficient venous drainage does exist, then type III cases may be treated as type IV cases, with resection of the lesion alone.

A number of general principles governing resection of these complex lesions may be elicited from the literature. A multidisciplinary team should be considered mandatory for successful limb salvage in these cases. This involves not only the orthopaedic and vascular surgeons but also allied health professionals including physiotherapists, dieticians and occupational therapists. Resections should only be performed in a specialized tertiary-level institution with both orthopaedic and vascular surgical services familiar with the management of complex soft tissue sarcomas. Radiological and theatre departments should have angiographic capabilities on site. Additionally, plastic and reconstructive surgery may be necessitated by the nature and size of tissue resected, and thus access to this specialty should be easily available if required.

The required volume of tissue that the operating surgeon must resect to ensure an adequate and wide margin can be determined by the tissue surrounding the lesion. Fascia is considered impenetrable to tumour cells, and thus may act as a margin in its own right. However, skin, fat and muscle are easily penetrated and thus 2-3 cm of these tissues must be excised[12].

Difficulty arises when determining safe margins where major vessels are in the surgical field. Inevitably, a major vessel must be sacrificed if tumour originates within the lumen of the vessel itself[5]. Where tumour surrounds a vessel, or infiltrates its wall, resection of the vessel may also become necessary[5,13].

The adventitial layer of the vessel may be considered an acceptable margin. Some authors have advocated longitudinal division of the adventitia on the side opposite to the tumour[5,14-16]. The layer is opened like a book, allowing the vessel to be mobilized and released. Moreover, patch-type reconstructions may be an option where tumour is in very limited contact with the vessel wall[12]. Cipriano et al[12] note that the pseudocapsule that typically surrounds soft tissue sarcomas should not be considered equivalent to fascia, and should be treated as a contaminated plane.

The initial strategy in these procedures is to mobilise the tumour, while controlling and preserving vascular structures proximal and distal to the lesion[15]. As with all tumour surgery, one of the primary goals is to prevent contamination of the surgical bed by tumour cells. For this reason, Matsumoto et al[17] introduced the concept of complete isolation of the tumour mass once mobilized using a vinyl sheet, drape or gauze. Attention must then turn to the careful dissection of adjacent or involved vascular structures.

Ischaemic time of the limb must be a consideration throughout the procedure. Vessel clamping and division should be performed just prior to complete excision of the tumour. Baxter et al[18] suggest the administration of 50 units/kg of heparin 5 min prior to the application of clamps. Emori et al[8] administered 1 mg/kg of heparin immediately prior to clamping. In their series, Muramatsu et al[19] preferred the administration of 2000-5000 U of intravenous heparin immediately following vascular anastomosis. Following complete division of the vessels and final excision of the tumour mass, arterial and venous shunts may also be placed to reduce ischaemic time. The routine lowering of ambient room temperature in the operating theatre at the time of vascular reconstruction has also been reported[19].

Once the tumour mass has been excised, with control of compromised vessels, attention must then turn to vascular reconstruction. A number of vascular reconstructive options are available to the surgeon, and the choice of specific graft depends on the length and caliber of vessel required, the availability of suitable venous graft in the contralateral limb, and surgeon experience and preference. Options variously described in the literature include contralateral superficial femoral vein graft, reversed long saphenous vein graft, or synthetic grafts such as polytetrafluoroethylene or polyethylene terephthalate[5,7,8,15,18-22].

Routinely patients should receive prophylactic antibiotic treatment, and a closed suction drain may also be placed at time of closure. In the post-operative setting, follow-up should be as standard for soft tissue sarcoma resections. However, additionally the patency of vascular anastomoses should be followed at regular intervals.

It should be noted that while limb salvage is possible, the precise manner in which this is achieved has been variously described. Given the nature of the pathology, large randomized control trials would be both difficult to construct and ethically inappropriate. As such, there is some controversy in the literature regarding some aspects of treatment of this patient cohort. In particular, the optimal choice of substitute vessel graft is not well established, and whether venous reconstruction is necessary also remains unclear.

Arterial reconstruction following resection is clearly indicated since the limb is unlikely to survive due to the high risk of ischaemia. Evidence in the literature favouring similarly aggressive venous reconstruction is less robust. Fortner et al[2] and Imparato et al[23] report some of the earliest experiences of venous reconstruction. In general terms, however, reports of venous reconstruction in the literature are less frequently encountered. Moreover, in those reports where venous reconstruction was performed, follow-up data is occasionally absent and difficult to interpret[6,23,24].

Patients undergoing venous resection without reconstruction have been observed to experience post-operative oedema, discoloration of the limb and venous eczema[22,25]. Some authors have described successful management of oedema through use of simple elevation and elastic support[6,23]. Additionally, it has been argued that limb oedema may be more reflective of lymphatic disruption than venous deficiency[26]. Furthermore, both Tsukushi et al[27] and Adelani et al[28] have found no reduction in post-operative oedema when venous reconstruction was performed.

Despite these observations, a majority of reports describe attempts made by surgeons to reconstruct the venous system in every case, or at least in those cases where sufficient concern exists for collateral flow[5,7,8,18,19,21]. It may well be that the rate of post-operative oedema correlates closely with the degree of disruption of venous collaterals at the time of surgical resection.

Concerning the specific choice of material for vascular reconstructions, there appears to be no clear evidence supporting one material over another. Both autologous vein and prosthetic material have been used successfully (Table 1). Some authors have preferred the use of autologous material in preference to prosthetic graft[5,22,29].

| Ref. | Number (n) | Graft material (n) | Patency |

| Imparato et al[23] | 3 | Saphenous | |

| Nambisan et al[35] | 6 | PTFE | 33% |

| Steed et al[36] | 1 | Saphenous | |

| Karakousis et al[37] | 9 | PTFE | 0% |

| Kawai et al[26] | 7 | PTFE (5), saphenous (2) | 14% |

| Koperna et al[29] | 13 | Saphenous (8), PTFE (4), PETE (1) | 77% |

| Karakousis et al[6] | 15 | PTFE (14), saphenous (1) | |

| Hohenberger et al[13] | 10 | Saphenous (6), PTFE (4) | 72% |

| Bonardelli et al[14] | 5 | Saphenous (3), transposition (2) | 100% |

| Leggon et al[24] | 8 | Saphenous (5), femoral (2), PETE (1) | |

| Schwarzbach et al[5] | 12 | PTFE (10), saphenous (2) | 58% |

| Nishinari et al[22] | 17 | Saphenous (12), PTFE (3), PETE (2) | 82% |

| Song et al[21] | 9 | Saphenous (4), femoral vein (2), Allograft (3) | 78% |

| López-Anglada Fernández et al[15] | 1 | PTFE (1) | 100% |

| Muramatsu et al[19] | 12 | Saphenous (10), PTFE (2) | |

| Emori et al[8] | 9 | PTFE (9) | |

| Viñals Viñals et al[38] | 1 | Saphenous (1) | 100% |

| Umezawa et al[7] | 13 | Saphenous (13) |

The great saphenous vein remains a common and popular choice of graft for both arterial and venous reconstructions. Its length and diameter is generally amenable to use as a vascular conduit, and it is easily accessible for harvest at the time of operation. Further, saphenous vein graft has been reported to afford superior patency rates at four years when compared with prosthetic graft (68% vs 38%)[30]. There is not universal agreement on this point, and other reports suggest that there is no superior advantage to autologous graft over synthetic graft in terms of patency in the longer term[2,23,31].

Against these observations, it has been argued that saphenous graft may be of inadequate length for reconstructive purposes, and harvest carries additional morbidity in terms of longer operative time, and additional surgical exposure and wounds. Regardless of the material chosen, it should be of sufficient length and caliber to appropriately and securely reconstruct the resected vessel.

Limb salvage surgery should seek to leave the patient with a limb which functions superiorly when compared with amputation and prosthetic replacement. This should not be at the expense of oncological outcome[12]. The literature has relatively few reports concerning the functional outcomes of those patients undergoing limb-salvage surgery with concomitant vascular reconstruction. In one report of pooled data, 76% of a cohort of 58 patients for whom functional outcome measures were available reported having a “functional limb”[24].

Wound complications, tumour size and motor nerve sacrifice have been identified as determinants of overall functional outcome after limb-salvage surgery and radiotherapy for soft tissue sarcoma[32,33]. Ghert et al[20] matched each of a cohort of patients undergoing limb salvage and vascular reconstruction with two other patients not undergoing vascular reconstruction, on the basis of tumour size, wound complications and pre-operative toronto extremity salvage score (TESS) score. The TESS score is a functional measure of physical disability, specifically designed for patients with extremity sarcoma[34]. At one year post-operatively, those patients undergoing vascular reconstruction had only slightly lower post-operative TESS scores.

Schwarzbach et al[5] found that of nine patients interviewed regarding limb function, five reported their outcome as excellent, three felt their outcome was good, while one patient reported a poor outcome due to contracture.

It is possible to obtain reasonably good survival rates with careful pre-operative planning and appropriate and timely intervention. Recurrence of tumour remains an issue however. Schwarzbach et al[5] report recurrence in 15.8% (n = 3) of 19 patients in their study. A slightly higher figure of 21% has been reported by Song et al[21].

Two-year survival has been variously reported in the literature, ranging from 58.6% to 70.4%[5,8,22]. At five years post surgery, approximately one in two patients will have died from their disease, with reported figures ranging from 42.4% to 70%[5,8,21,22].

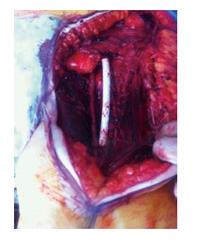

A 73-year-old woman presented with a high grade, stage III leiomyosarcoma in her left inguinal region. The lesion was present for approximately one year prior to presentation and measured 11 centimeters in maximum diameter. CT and MRI demonstrated a large tumour mass invading the left common femoral vein, and surrounded the anterior aspect of the common femoral artery for greater than 180 degrees of the vessel surface. The tumour mass was intimately related to adjacent vessels and was found to interdigitate the common femoral bifurcation (Figure 2). The lesion was resected en-bloc with concomitant vascular reconstruction (Figure 3). Arterial reconstruction involved an end-to-end anastomosis from the external iliac artery to superficial femoral artery using an 8-milimetre Gortex synthetic graft. The contralateral long saphenous vein was harvested for venous reconstruction. An end-to-end anastomosis between the superficial femoral vein and external iliac vein was performed.

Post-operatively, the patient’s wound healed without complication. In view of the necessary vascular reconstruction, anti-coagulation with warfarin was commenced. At one month post-operatively however, she required ileo-femoral-popliteal thrombectomy for graft thrombosis. The patient completed a course of adjuvant radiotherapy to the tumour bed (66 Gy in 33 fractions).

A 16-year-old young woman presented to clinic with a 5-year history of progressive swelling in her left calf. Multi-modality investigations including CT angiogram, MRI and MRA, and tissue biopsy confirmed a 4.2 cm × 5.6 cm × 7.2 cm hypervascular and heterogenous mass, with features of central necrosis, in the posterior compartment of the upper calf (Figure 4). The tumour mass was found to lie in the neurovascular plain, with multiple vessels feeding from the peroneal and posterior tibial arteries. The anterior tibial artery was uninvolved. Microscopy confirmed an alveolar soft part sarcoma.

The surgical strategy involved pre-operative embolization of the feeder vessels as described. The following day, the tumour mass was resected en-bloc with concomitant vascular reconstruction. Popliteal and anterior tibial vessels were preserved. Peroneal and posterior tibial vessels were resected with tumour. The posterior tibial artery was revascularized from approximately 5 cm beyond its origin mid-calf using a reversed long saphenous vein graft harvested from the contralateral leg. Anastomosis was performed in an end-to-end fashion.

At the time of diagnosis, the patient was found to have lung metastases. She underwent adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy to both lungs (19.5 Gy in 13 fractions) and to the tumour bed (50.4 Gy in 28 fractions). At 48 mo follow-up, the patient was well without further complications.

A 56-year-old man presented with a 2-mo history of painless swelling in the right popliteal fossa. He had a history of having lentigo maligna excised from his ear some 5 mo earlier, but was otherwise healthy. MRI and MRA revealed a large soft tissue mass in the superior popliteal fossa measuring 8.5 cm × 7.8 cm × 4.5 cm in dimension. The tumour encased the popliteal artery for at least 270 degrees of its circumference over a distance of 8 cm (Figure 5). Subsequent biopsy revealed grade II stage IB leiomyosarcoma.

The patient received pre-operative radiotherapy (50 Gy in 25 fractions) before definitive surgical resection. Arterial reconstruction required reverse long saphenous vein graft with end-to-end anastomosis. Venous reconstruction was not necessary. Post-operatively, there were no major vascular complications.

Patients presenting with soft tissue sarcomas that involve major vascular structures represent a unique and complex cohort of patients. Advances in both orthopaedic and vascular surgery have made it possible to successfully resect these lesions and achieve limb-salvage while also maintaining reasonable function. A multidisciplinary approach with careful pre-operative evaluation is essential to improve outcome.

The authors would like to thank Professor, Dr. med. Matthias Schwarzbach and Elsevier for kindly allowing us to use Figure 1 in the text.

P- Reviewer: de Bree E, Sakamoto A, Ueda H S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Ruka W, Emrich LJ, Driscoll DL, Karakousis CP. Prognostic significance of lymph node metastasis and bone, major vessel, or nerve involvement in adults with high-grade soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer. 1988;62:999-1006. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fortner JG, Kim DK, Shiu MH. Limb-preserving vascular surgery for malignant tumors of the lower extremity. Arch Surg. 1977;112:391-394. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gilbert NF, Cannon CP, Lin PP, Lewis VO. Soft-tissue sarcoma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:40-47. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 71] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cormier JN, Pollock RE. Soft tissue sarcomas. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:94-109. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 334] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Schwarzbach MH, Hormann Y, Hinz U, Bernd L, Willeke F, Mechtersheimer G, Böckler D, Schumacher H, Herfarth C, Büchler MW. Results of limb-sparing surgery with vascular replacement for soft tissue sarcoma in the lower extremity. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:88-97. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 94] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Karakousis CP, Karmpaliotis C, Driscoll DL. Major vessel resection during limb-preserving surgery for soft tissue sarcomas. World J Surg. 1996;20:345-349; discussion 350. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 55] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Umezawa H, Sakuraba M, Miyamoto S, Nagamatsu S, Kayano S, Taji M. Analysis of immediate vascular reconstruction for lower-limb salvage in patients with lower-limb bone and soft-tissue sarcoma. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66:608-616. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Emori M, Hamada K, Omori S, Joyama S, Tomita Y, Hashimoto N, Takami H, Naka N, Yoshikawa H, Araki N. Surgery with vascular reconstruction for soft-tissue sarcomas in the inguinal region: oncologic and functional outcomes. Ann Vasc Surg. 2012;26:693-699. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bains R, Magdum A, Bhat W, Roy A, Platt A, Stanley P. Soft tissue sarcoma - A review of presentation, management and outcomes in 110 patients. Surgeon. 2014;Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Eggermont AM, Schraffordt Koops H, Klausner JM, Kroon BB, Schlag PM, Liénard D, van Geel AN, Hoekstra HJ, Meller I, Nieweg OE. Isolated limb perfusion with tumor necrosis factor and melphalan for limb salvage in 186 patients with locally advanced soft tissue extremity sarcomas. The cumulative multicenter European experience. Ann Surg. 1996;224:756-764; discussion 764-765. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 349] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 362] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wray CJ, Benjamin RS, Hunt KK, Cormier JN, Ross MI, Feig BW. Isolated limb perfusion for unresectable extremity sarcoma: results of 2 single-institution phase 2 trials. Cancer. 2011;117:3235-3241. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cipriano CA, Wunder JS, Ferguson PC. Surgical Management of Soft Tissue Sarcomas of the Extremities. Oper Tech Orthop. 2014;24:79-84. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hohenberger P, Allenberg JR, Schlag PM, Reichardt P. Results of surgery and multimodal therapy for patients with soft tissue sarcoma invading to vascular structures. Cancer. 1999;85:396-408. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bonardelli S, Nodari F, Maffeis R, Ippolito V, Saccalani M, Lussardi L, Giulini S. Limb salvage in lower-extremity sarcomas and technical details about vascular reconstruction. J Orthop Sci. 2000;5:555-560. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | López-Anglada Fernández E, Rubio Sanz J, Braña Vigil A. Vascular reconstruction during limb preserving surgery in the treatment of lower limb sarcoma: A report on four cases. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2009;53:386-393. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ceraldi CM, Wang TN, O’Donnell RJ, McDonald PT, Granelli SG. Vascular reconstruction in the resection of soft tissue sarcoma. Perspect Vasc Surg. 2000;12:67-83. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Matsumoto S, Kawaguchi N, Manabe J, Matsushita Y. “In situ preparation”: new surgical procedure indicated for soft-tissue sarcoma of a lower limb in close proximity to major neurovascular structures. Int J Clin Oncol. 2002;7:51-56. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Baxter BT, Mahoney C, Johnson PJ, Selmer KM, Pipinos II, Rose J, Neff JR. Concomitant arterial and venous reconstruction with resection of lower extremity sarcomas. Ann Vasc Surg. 2007;21:272-279. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Muramatsu K, Ihara K, Miyoshi T, Yoshida K, Taguchi T. Clinical outcome of limb-salvage surgery after wide resection of sarcoma and femoral vessel reconstruction. Ann Vasc Surg. 2011;25:1070-1077. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ghert MA, Davis AM, Griffin AM, Alyami AH, White L, Kandel RA, Ferguson P, O’Sullivan B, Catton CN, Lindsay T. The surgical and functional outcome of limb-salvage surgery with vascular reconstruction for soft tissue sarcoma of the extremity. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:1102-1110. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 76] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Song TK, Harris EJ, Raghavan S, Norton JA. Major blood vessel reconstruction during sarcoma surgery. Arch Surg. 2009;144:817-822. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Nishinari K, Wolosker N, Yazbek G, Zerati AE, Nishimoto IN. Venous reconstructions in lower limbs associated with resection of malignancies. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:1046-1050. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Imparato AM, Roses DF, Francis KC, Lewis MM. Major vascular reconstruction for limb salvage in patients with soft tissue and skeletal sarcomas of the extremities. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1978;147:891-896. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Leggon RE, Huber TS, Scarborough MT. Limb salvage surgery with vascular reconstruction. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;207-216. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Matsushita M, Kuzuya A, Mano N, Nishikimi N, Sakurai T, Nimura Y, Sugiura H. Sequelae after limb-sparing surgery with major vascular resection for tumor of the lower extremity. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33:694-699. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kawai A, Hashizume H, Inoue H, Uchida H, Sano S. Vascular reconstruction in limb salvage operations for soft tissue tumors of the extremities. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;215-222. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tsukushi S, Nishida Y, Sugiura H, Nakashima H, Ishiguro N. Results of limb-salvage surgery with vascular reconstruction for soft tissue sarcoma in the lower extremity: comparison between only arterial and arterovenous reconstruction. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:216-220. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Adelani MA, Holt GE, Dittus RS, Passman MA, Schwartz HS. Revascularization after segmental resection of lower extremity soft tissue sarcomas. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95:455-460. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Koperna T, Teleky B, Vogl S, Windhager R, Kainberger F, Schatz KD, Kotz R, Polterauer P. Vascular reconstruction for limb salvage in sarcoma of the lower extremity. Arch Surg. 1996;131:1103-1107; discussion 1108. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Veith FJ, Gupta SK, Ascer E, White-Flores S, Samson RH, Scher LA, Towne JB, Bernhard VM, Bonier P, Flinn WR. Six-year prospective multicenter randomized comparison of autologous saphenous vein and expanded polytetrafluoroethylene grafts in infrainguinal arterial reconstructions. J Vasc Surg. 1986;3:104-114. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 848] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 705] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wuisman P, Grunert J. [Blood vessel transfer allowing avoidance of surgical rotation or amputation in the management of primary malignant tumors of the knee]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1994;80:720-727. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Davis AM, O’Sullivan B, Bell RS, Turcotte R, Catton CN, Wunder JS, Chabot P, Hammond A, Benk V, Isler M. Function and health status outcomes in a randomized trial comparing preoperative and postoperative radiotherapy in extremity soft tissue sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4472-4477. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 186] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Davis AM, Sennik S, Griffin AM, Wunder JS, O’Sullivan B, Catton CN, Bell RS. Predictors of functional outcomes following limb salvage surgery for lower-extremity soft tissue sarcoma. J Surg Oncol. 2000;73:206-211. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Davis AM, Wright JG, Williams JI, Bombardier C, Griffin A, Bell RS. Development of a measure of physical function for patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma. Qual Life Res. 1996;5:508-516. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 388] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Nambisan RN, Karakousis CP. Vascular reconstruction for limb salvage in soft tissue sarcomas. Surgery. 1987;101:668-677. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Steed DL, Peitzman AB, Webster MW, Ramasastry SS, Goodman MA. Limb sparing operations for sarcomas of the extremities involving critical arterial circulation. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1987;164:493-498. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 37. | Karakousis CP, Emrich LJ, Vesper DS. Soft-tissue sarcomas of the proximal lower extremity. Arch Surg. 1989;124:1297-1300. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Viñals Viñals JM, Gomes Rodrigues TA, Perez Sidelnikova D, Serra Payro JM, Palacin Porté JA, Higueras Suñe C. [Vascular reconstruction for limb preservation during sarcoma surgery: a case series and a management algorithm]. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2013;57:21-26. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |