Published online Sep 26, 2016. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v8.i9.547

Peer-review started: May 9, 2016

First decision: June 13, 2016

Revised: July 12, 2016

Accepted: July 29, 2016

Article in press: August 1, 2016

Published online: September 26, 2016

Processing time: 137 Days and 5 Hours

To determine the prevalence of depression and its risk factors among patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) treated in German primary care practices.

Longitudinal data from nationwide general practices in Germany (n = 1072) were analyzed. Individuals initially diagnosed with CHD (2009-2013) were identified, and 59992 patients were included and matched (1:1) to 59992 controls. The primary outcome measure was an initial diagnosis of depression within five years after the index date among patients with and without CHD. Cox proportional hazards models were used to adjust for confounders.

Mean age was equal to 68.0 years (SD = 11.3). A total of 55.9% of patients were men. After a five-year follow-up, 21.8% of the CHD group and 14.2% of the control group were diagnosed with depression (P < 0.001). In the multivariate regression model, CHD was a strong risk factor for developing depression (HR = 1.54, 95%CI: 1.49-1.59, P < 0.001). Prior depressive episodes, dementia, and eight other chronic conditions were associated with a higher risk of developing depression. Interestingly, older patients and women were also more likely to be diagnosed with depression compared with younger patients and men, respectively.

The risk of depression is significantly increased among patients with CHD compared with patients without CHD treated in primary care practices in Germany. CHD patients should be routinely screened for depression to ensure improved treatment and management.

Core tip: This is a retrospective study to determine the prevalence of depression and its risk factors among patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) treated in German primary care practices. Fifty-nine thousand nine hundred and ninety-two patients with CHD from German primary care practices were included and matched to 59992 controls. After a five-year follow-up, 21.8% of the CHD group and 14.2% of the control group were diagnosed with depression. In the multivariate regression model, CHD was a strong risk factor for developing depression.

- Citation: Konrad M, Jacob L, Rapp MA, Kostev K. Depression risk in patients with coronary heart disease in Germany. World J Cardiol 2016; 8(9): 547-552

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v8/i9/547.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v8.i9.547

Coronary heart disease (CHD), as one of the cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), is a leading chronic medical condition worldwide, with a large number of affected patients[1,2]. CHD is characterized by the manifestation of atherosclerosis in coronary arteries, that is, narrowed coronary arteries and reduced perfusion of the heart. This can lead to a myocardial infarction[3,4]. CVD and CHD are major causes of death around the world[1], particularly in Germany, where CVD was responsible for 338056 deaths in 2014 (38.9% of the total number of deaths)[5]. In this context, the CHD-related mortality rate was approximately 20%, with a total of 69890 deaths in 2014[6].

Approximately 6 million people are affected by CHD in Germany[7]. Due to improvements in various therapies, mortality rates have decreased worldwide. Nevertheless, the prevalence of CHD is increasing, partly due to the demographic aging of the population, increased prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, and patients’ improved survival after a cardiovascular event[2]. While the lifetime prevalence of CHD among German women remained unchanged at approximately 7% between 2003 and 2012, it increased from 8% in 2003 to 10% in 2010 among German men[8].

It is known that the risk of depression is significantly increased among individuals with chronic diseases (e.g., CHD), as they exhibit 2-3 times higher rates than the general population[9,10]. Depression significantly worsens the health state of patients with chronic diseases[11]. Overall, depression adversely affects the course, complications, and management of CHD[10,12]. Furthermore, depression in patients with CHD contributes to poor functional and cardiovascular outcomes, poor quality of life, and increased mortality[13-16].

Depression is frequently observed in patients with CHD[14]. Previous studies showed that up to 30% of patients with CHD suffer from depression[17]. Most published studies examined hospital patients or were based on a small number of patients[18]. Thus, little is known about the prevalence of depression among outpatients with CHD[14]. Because no relevant German data exist, the goal of this study was to estimate the prevalence and the risk factors of depression among CHD patients treated in primary care practices in Germany.

The Disease Analyzer database (IMS HEALTH) compiles drug prescriptions, diagnoses, and basic medical and demographic data obtained directly and in anonymous format from computer systems used by general practitioners[19]. IMS has monitored diagnoses (ICD-10), prescriptions (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification System), and the quality of reported data according to a number of criteria (e.g., completeness of documentation, linkage between diagnoses and prescriptions). In Germany, the sampling methods used to select physicians’ practices were appropriate for obtaining a representative database of primary care practices[19]. The statistics regarding prescriptions for several drugs were very similar to data available in pharmaceutical prescription reports[19]. The age groups suffering from given diagnoses in the Disease Analyzer were also consistent with those in corresponding disease registries[19].

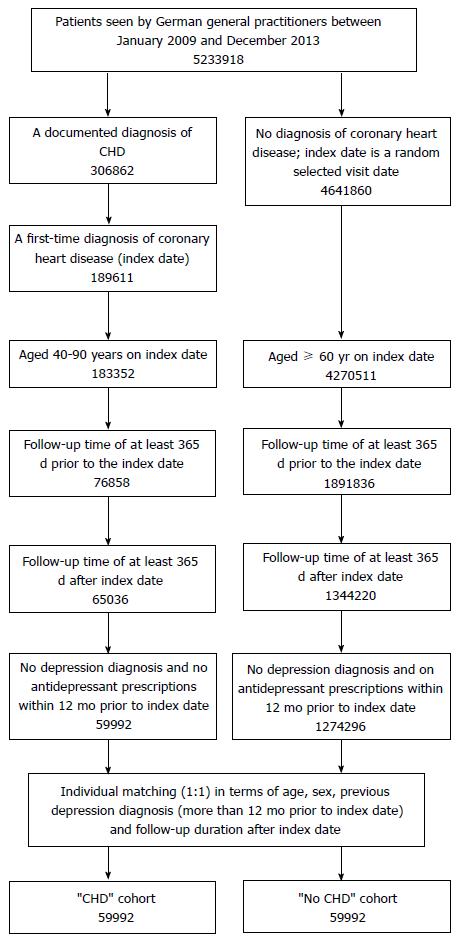

This study included patients between 40 and 90 years of age who were being treated in 1072 primary care practices and who received an initial CHD diagnosis (ICD 10: I25) during the index period (January 2009 to December 2013). Follow-up lasted a maximum of five years and ended in October 2015. Patients were excluded if they were diagnosed with depression (ICD-10: F32, F33) or received any antidepressant prescription (ATC: N06A) within 12 mo prior to CHD diagnosis (index date). A total of 59992 CHD patients remained after these exclusion criteria were applied. Finally, 59992 controls without CHD, depression diagnosis or antidepressant prescriptions within 12 mo prior to index date (any randomly selected visit date) were chosen and matched (1:1) to CHD cases based on age, sex, past depression diagnosis (more than 12 mo prior to index date), and follow-up duration after the index date (Figure 1).

The primary outcome was the diagnosis of depression recorded in the database between the index date and the end of follow-up. Depression diagnoses were based on primary care documentation.

Demographic data included age and gender. Other chronic conditions that could be associated with depression risk were determined based on primary care diagnoses and included as confounders: Diabetes mellitus (E10-14), hypertension (I10), dementia (F01, F03, G30), stroke (F63, F64, G45), heart failure (I10), myocardial infarction (I21-23), cardiac arrhythmias (I46-I49), osteoporosis (M80, M81), cancer (C00-C98), and osteoarthritis (M15-19).

Descriptive statistics were obtained, and differences in patients’ characteristics (CHD vs controls) were assessed using Wilcoxon tests for paired samples or McNemar’s tests. Analyses of depression-free survival were carried out using Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests. Cox proportional hazards models (dependent variable: Depression) were used to adjust for confounders. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.3.

Patient characteristics are displayed in Table 1. A total of 119984 patients were included in the CHD and control groups. Mean age was equal to 68.0 years (SD = 11.3 years), and 55.9% of the patients were men. The proportion of patients with a prior depression diagnosis (> 12 mo prior to the index date) was 11.1% in both groups. All chronic conditions (i.e., diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmias, heart failure, stroke, cancer, dementia, osteoarthritis and osteoporosis) occurred more frequently in the CHD group than in the control group (P < 0.001).

| Variables | CHD group | Control group | P value |

| n | 59992 | 59992 | |

| Age (yr) | 68.0 (11.3) | 68.0 (11.3) | 1 |

| Aged ≤ 60 (%) | 26.7 | 26.7 | 1 |

| Aged 61-70 (%) | 26.5 | 26.5 | 1 |

| Aged 71-80 (%) | 32.6 | 32.6 | 1 |

| Aged > 80 (%) | 14.3 | 14.3 | 1 |

| Males (%) | 55.9 | 55.9 | 1 |

| Follow-up time (yr) | 3.6 (1.5) | 3.6 (1.5) | 1 |

| Past depression diagnosis (> 12 mo prior to index date) | 11.1 | 11.1 | 1 |

| Co-diagnosis (%) | |||

| Diabetes | 35.9 | 23.4 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 78.7 | 59.4 | < 0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 11.8 | 0.6 | < 0.001 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 25.7 | 14.3 | < 0.001 |

| Heart failure | 18.4 | 7.4 | < 0.001 |

| Stroke | 9.2 | 5.6 | < 0.001 |

| Cancer | 11.9 | 11.1 | < 0.001 |

| Dementia | 4.9 | 4.5 | < 0.001 |

| Osteoarthritis | 31.4 | 27.6 | < 0.001 |

| Osteoporosis | 10.3 | 8.4 | < 0.001 |

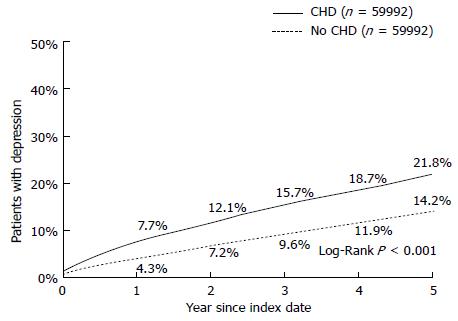

Kaplan-Meier curves for time to depression diagnosis in the CHD and control groups are displayed in Figure 2. Overall, 7.7% of CHD patients and 4.3% of matched controls had developed depression after one year of follow-up (P < 0.001). After a five-year follow-up period, 21.8% of the CHD group and 14.2% of the control group were diagnosed with depression (P < 0.001).

The results of the multivariate Cox regression model for depression diagnosis in CHD patients and matched controls are illustrated in Table 2. CHD was a strong risk factor for the development of depression (HR = 1.54, 95%CI: 1.49-1.59, P < 0.001). Prior depressive episodes also increased the risk of renewed depression diagnosis (HR = 3.44; 95%CI: 3.32-3.56, P < 0.001). Patients in the age group ≤ 60 had a higher risk of depression compared with patients aged 61-70 years (HR = 1.50, 95%CI: 1.44-1.57, P < 0.001). Patients in the age groups 71-80 and > 80 years were also more likely to be diagnosed with depression than patients aged 61-70 years (HR = 1.08 (95%CI: 1.04-1.13) and 1.16 (95%CI: 1.10-1.23), respectively, both P < 0.001). Furthermore, other chronic co-diagnoses increased the risk of depression (P < 0.001). By contrast, men had a lower risk of being depressed than women (HR = 0.67; 95%CI: 0.65-0.69).

| Variables | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P value |

| CHD | 1.54 (1.49-1.59) | < 0.001 |

| Past depression diagnosis | 3.44 (3.32-3.56) | < 0.001 |

| Aged ≤ 60 vs 61-70 | 1.50 (1.44-1.57) | < 0.001 |

| Aged 71-80 vs 61-70 | 1.08 (1.04-1.13) | < 0.001 |

| Aged > 80 vs 61-70 | 1.16 (1.10-1.23) | < 0.001 |

| Male gender | 0.67 (0.65-0.69) | < 0.001 |

| Dementia | 1.24 (1.17-1.31) | < 0.001 |

| Stroke | 1.22 (1.16-1.28) | < 0.001 |

| Cancer | 1.19 (1.14-1.24) | < 0.001 |

| Osteoporosis | 1.18 (1.13-1.24) | < 0.001 |

| Heart failure | 1.17 (1.12-1.22) | < 0.001 |

| Osteoarthritis | 1.15 (1.11-1.19) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1.10 (1.06-1.14) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 1.08 (1.04-1.12) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1.06 (1.03-1.10) | < 0.001 |

In this retrospective study of 119984 patients treated in primary care practices in Germany, we showed that CHD was associated with an increased risk of developing depression. Moreover, prior depressive episodes and co-diagnoses such as dementia, stroke, cancer, osteoporosis, heart failure, osteoarthritis, hypertension, cardiac arrhythmias, and diabetes were also risk factors for this psychiatric disorder. Individuals aged 60 years or younger and individuals aged over 70 years were more likely to develop depression compared with patients aged 61-70 years. Finally, men were at a lower risk of being diagnosed with depression than women.

CHD is a chronic disease that has an important impact on patients’ physical and psychological aspects of life. Indeed, patients affected by CHD are more likely to become depressed than those without CHD. Several studies estimated that depression affects between 17.2% and 30.6% of CHD patients[20-23] but only approximately 7% of the general population[17]. More recently, Ren et al[18] performed a meta-analysis on the prevalence of depression among CHD patients in hospital and community settings. In the 23 hospital-based studies (the total number of patients equalled 5236), the prevalence of depression ranged from 22.8% to 84.0%, with 0.5% to 25.44% categorized as severe forms[18]. In the four community-based studies (the total number of patients equalled 1353), depression prevalence ranged from 34.6% to 45.0%, with 3.1%-6.9% classified as major depressive disorders[18]. This meta-analysis clearly indicates that although hospital and community settings have a similar total number of patients, more hospital-based than community-based studies have been conducted and results differ between the two settings. Thus, because the findings of hospital-based studies cannot be extrapolated to the community population, new studies must be conducted outside the hospital setting. In line with previous data, we found that after five years of follow-up, 21.8% of CHD patients were depressed, whereas only 14.2% of controls exhibited this psychiatric condition. This important result underlines the fact that CHD increases the odds that patients treated in general practices in Germany develop depression.

Interestingly, the relationship between depression and CHD is bidirectional; thus, depression is also a risk factor for CHD[17]. In 2010, Taylor et al[24] showed that CHD risk, which was similar at baseline to that of the general population, increased within the first two years following the diagnosis of major depressive disorders. The main hypothesis proposed to explain the bidirectional relationship between CHD and depression asserts that they share common risk factors. First, stress is known to increase the odds of developing these two diseases[24,25]. Indeed, stress has a major impact on the cardiovascular system and on psychological aspects of individuals’ life and thus increases the occurrence of both disorders. Importantly, beyond the influence of stress, behavioral disorders can also lead to CHD and depression. In fact, such psychiatric preconditions are often associated with a loss of interest in daily tasks (i.e., eating or engaging in physical activity)[17], which may indirectly lead to depression and disrupt the body’s energetic balance. Finally, several authors suggested that CHD and depression share common genetic mechanisms that are involved in inflammation pathways and oxidative stress[17]. For example, the length of leukocyte telomeres is negatively associated with major depressive disorders and coronary artery disease[26,27].

In this study, we found that prior depressive episodes, dementia, stroke, cancer, osteoporosis, heart failure, osteoarthritis, hypertension, cardiac arrhythmias, and diabetes were additional risk factors for depression. Most of these diseases are chronic conditions that may reduce affected patients’ quality of life. Of note, the strongest predictor was past depressive episodes (HR = 3.44; 95%CI: 3.32-3.56). In fact, depression is a highly recurrent disorder that is difficult for physicians to treat and manage[28]. Our data also showed that men were at a lower risk of developing this psychiatric disorder than women. In 2005, Perez et al[29] conducted a study of 345 patients with acute coronary syndrome and found that women were more likely to be diagnosed with depression than men (OR = 2.40, 95%CI: 1.44-4.00)[29]. Although several authors hypothesized that there are important gender differences in hormones, genes, and brain structures, our discovery may be explained by artefacts because women tend to be more emotional and are more inclined to seek medical help than men. Finally, we found that individuals aged 60 years or younger and those aged over 70 years have a higher risk of developing depression than patients aged 61-70 years. Although this finding is new and surprising, one hypothesis maintains that individuals aged 61-70 years receive optimal treatment and management. Because younger patients are less likely to develop chronic diseases, medical follow-up is difficult and they may be at higher risk of developing depression. However, very elderly patients are less compliant and may not follow the treatment prescribed by their general practitioner.

This study had several limitations. The database contained no valid information on biological markers associated with CHD. Furthermore, no detailed documentation concerning the diagnosis of depression, namely, the severity of depression, was available. Data on socioeconomic status and lifestyle-related risk factors were also unavailable. Each patient was observed retrospectively in only one practice. If a patient visited a different doctor - which is common in Germany - the visit was not documented.

In conclusion, this study showed that CHD patients were at a higher risk of developing depression than patients without CHD. Interestingly, prior depressive episodes, dementia, stroke, cancer, osteoporosis, heart failure, osteoarthritis, hypertension, cardiac arrhythmias, and diabetes were additional risk factors for this psychiatric condition. Finally, we found that individuals aged 60 years or younger and those aged over 70 years have a higher risk of developing depression than patients aged 61-70 years. Further investigations are needed to gain a better understanding of the association between depression and CHD in general practices in Germany.

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a leading chronic medical condition worldwide, with a large number of affected patients. CHD is characterized by the manifestation of atherosclerosis in coronary arteries, that is, narrowed coronary arteries and reduced perfusion of the heart. This can lead to a myocardial infarction. CHD is one of the causes of death around the world. It is known that the risk of depression is significantly increased among individuals with chronic diseases. Overall, depression adversely affects the course, complications, and management of CHD.

Thus, little is known about the prevalence of depression among outpatients with CHD. Because no relevant German data exist, the goal of this study was to estimate the prevalence and the risk factors of depression among CHD patients treated in primary care practices in Germany.

In this study, analyses were performed based on 119984 patients treated in primary care practices in Germany. At first, this is the first study using such large patient numbers; at second, the study cohort includes both high-risk patients and patients without CHD diagnosis.

This study showed that CHD patients were at a much higher risk of developing depression than patients without CHD, especially patients who additionally have further chronic co-diagnoses. Physicians who care for CHD patients should consider identification and treatment of depression a clinical practice.

CHD: Coronary heart disease; ICD: International classification of disease.

The authors did a retrospective analysis on a German cohort of 119984 patients to examine the association between CHD and the development of depression. Strength of this study lies in the great sample size, and it is a community-based study. In this study, the author determines the prevalence of depression and its risk factors in patients with coronary heart disease. They found that CHD was a strong risk factor for depression development in German population.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country of origin: Germany

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Gao DF, Tao J S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Nichols M, Townsend N, Scarborough P, Rayner M. Cardiovascular disease in Europe 2014: epidemiological update. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bansilal S, Castellano JM, Fuster V. Global burden of CVD: focus on secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Int J Cardiol. 2015;201 Suppl 1:S1-S7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | De Hert M, Cohen D, Bobes J, Cetkovich-Bakmas M, Leucht S, Ndetei DM, Newcomer JW, Uwakwe R, Asai I, Möller HJ. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. II. Barriers to care, monitoring and treatment guidelines, plus recommendations at the system and individual level. World Psychiatry. 2011;10:138-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 529] [Cited by in RCA: 580] [Article Influence: 41.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Libby P, Theroux P. Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2005;111:3481-3488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1083] [Cited by in RCA: 1183] [Article Influence: 62.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Statistisches Bundesamt. Todesursachen in Deutschland, 2014. Available from: http//www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/GesellschaftStaat/Gesundheit/Todesursachen/Todesursachen.html. |

| 6. | Statistisches Bundesamt. Die 10 häufigsten Todesfälle durch Herz-Kreislauf-Erkrankungen (Sterbefälle insgesamt, 2014). Available from: http// www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/GesellscaftStaat/Gesundheit/Todesursachen/Tabellen/HerzKreislaufErkrankungen.html. |

| 7. | Hamm C. Koronare Herzkrankheit. Was genau ist eigentlich eine KHK (2016)? Available from: http://www.ukgm.de/ugm_2/deu/ugi_kar/PDF/Flyer_KHK.pdf. |

| 8. | Koch-Institut R. Daten und Fakten: Ergebnisse der Studie “Gesundheit in Deutschland aktuell 2012”. Beiträge zur Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. 2016;. |

| 9. | Haddad M, Walters P, Phillips R, Tsakok J, Williams P, Mann A, Tylee A. Detecting depression in patients with coronary heart disease: a diagnostic evaluation of the PHQ-9 and HADS-D in primary care, findings from the UPBEAT-UK study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Katon WJ. Epidemiology and treatment of depression in patients with chronic medical illness. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13:7-23. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370:851-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2533] [Cited by in RCA: 2617] [Article Influence: 145.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lichtman JH, Froelicher ES, Blumenthal JA, Carney RM, Doering LV, Frasure-Smith N, Freedland KE, Jaffe AS, Leifheit-Limson EC, Sheps DS. Depression as a risk factor for poor prognosis among patients with acute coronary syndrome: systematic review and recommendations: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:1350-1369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 966] [Cited by in RCA: 825] [Article Influence: 75.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ruo B, Rumsfeld JS, Hlatky MA, Liu H, Browner WS, Whooley MA. Depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life: the Heart and Soul Study. JAMA. 2003;290:215-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 543] [Cited by in RCA: 575] [Article Influence: 26.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lichtman JH, Bigger JT, Blumenthal JA, Frasure-Smith N, Kaufmann PG, Lespérance F, Mark DB, Sheps DS, Taylor CB, Froelicher ES. Depression and coronary heart disease: recommendations for screening, referral, and treatment: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Prevention Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association. Circulation. 2008;118:1768-1775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 958] [Cited by in RCA: 951] [Article Influence: 55.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Celano CM, Huffman JC. Depression and cardiac disease: a review. Cardiol Rev. 2011;19:130-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sin NL, Yaffe K, Whooley MA. Depressive symptoms, cardiovascular disease severity, and functional status in older adults with coronary heart disease: the heart and soul study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:8-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chauvet-Gélinier JC, Trojak B, Vergès-Patois B, Cottin Y, Bonin B. Review on depression and coronary heart disease. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;106:103-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ren Y, Yang H, Browning C, Thomas S, Liu M. Prevalence of depression in coronary heart disease in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2014;127:2991-2998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Becher H, Kostev K, Schröder-Bernhardi D. Validity and representativeness of the “Disease Analyzer” patient database for use in pharmacoepidemiological and pharmacoeconomic studies. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;47:617-626. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F, Talajic M. Depression and 18-month prognosis after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1995;91:999-1005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1053] [Cited by in RCA: 964] [Article Influence: 32.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ziegelstein RC, Fauerbach JA, Stevens SS, Romanelli J, Richter DP, Bush DE. Patients with depression are less likely to follow recommendations to reduce cardiac risk during recovery from a myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1818-1823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 498] [Cited by in RCA: 493] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Davidson KW, Burg MM, Kronish IM, Shimbo D, Dettenborn L, Mehran R, Vorchheimer D, Clemow L, Schwartz JE, Lespérance F. Association of anhedonia with recurrent major adverse cardiac events and mortality 1 year after acute coronary syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:480-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Myers V, Gerber Y, Benyamini Y, Goldbourt U, Drory Y. Post-myocardial infarction depression: increased hospital admissions and reduced adoption of secondary prevention measures--a longitudinal study. J Psychosom Res. 2012;72:5-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Taylor V, McKinnon MC, Macdonald K, Jaswal G, Macqueen GM. Adults with mood disorders have an increased risk profile for cardiovascular disease within the first 2 years of treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55:362-368. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Nabi H, Kivimäki M, Batty GD, Shipley MJ, Britton A, Brunner EJ, Vahtera J, Lemogne C, Elbaz A, Singh-Manoux A. Increased risk of coronary heart disease among individuals reporting adverse impact of stress on their health: the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2697-2705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Simon NM, Smoller JW, McNamara KL, Maser RS, Zalta AK, Pollack MH, Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Wong KK. Telomere shortening and mood disorders: preliminary support for a chronic stress model of accelerated aging. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:432-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 384] [Cited by in RCA: 382] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mukherjee M, Brouilette S, Stevens S, Shetty KR, Samani NJ. Association of shorter telomeres with coronary artery disease in Indian subjects. Heart. 2009;95:669-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Burcusa SL, Iacono WG. Risk for recurrence in depression. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:959-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 775] [Cited by in RCA: 705] [Article Influence: 39.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Perez GH, Nicolau JC, Romano BW, Laranjeira R. [Depression and Acute Coronary Syndromes: gender-related differences]. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2005;85:319-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |