Published online Apr 26, 2013. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v5.i4.112

Revised: March 4, 2013

Accepted: March 15, 2013

Published online: April 26, 2013

Processing time: 89 Days and 21.8 Hours

Kounis syndrome is defined as the coexistence of acute coronary syndromes with situations associated with allergy or hypersensitivity, as well as anaphylactic or anaphylactoid reactions, to a variety of medical conditions, environmental and medication exposures. We report a case of Kounis-Zavras syndrome type I variant in the setting of aspirin-induced asthma, or the Samter-Beer triad of asthma, nasal polyps and aspirin allergy. When there is a young individual with no predisposing factors of atherosclerosis and apparent coronary lesion, with or without electrocardiography and biochemical markers of infarction, the possibility of Kounis syndrome should be kept in mind.

Core tip: When there is a young individual with no predisposing factors of atherosclerosis and apparent coronary lesion, with or without electrocardiography and biochemical markers of infarction, the possibility of Kounis syndrome should be kept in mind. In such a situation, intracoronary vasodilators, nitrates, nicorandil or diltiazem should be used before proceeding with a coronary intervention. An urgent eosinophil count should be done before proceeding with a coronary intervention to rule out coronary spasm.

- Citation: Prajapati JS, Virpariya KM, Thakkar AS, Abhyankar AD. A case of type I variant Kounis syndrome with Samter-Beer triad. World J Cardiol 2013; 5(4): 112-114

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v5/i4/112.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v5.i4.112

Kounis syndrome is defined as the coexistence of acute coronary syndromes with situations associated with allergy or hypersensitivity, as well as anaphylactic or anaphylactoid reactions, to a variety of medical conditions, environmental and medication exposures. Patients undergoing stent implantation receive several substances which have antigenic properties. Many etiologies have been reported[1,2], including drugs (antibiotics, analgesics, antineoplastics, contrast media, corticosteroids, intravenous anesthetics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, skin disinfectants, thrombolytics, anticoagulants), various conditions (angio-edema, bronchial asthma, rhinitis, nasal polyp, urticaria, food allergy, exercise-induced allergy, mastocytosis, serum sickness), environmental exposure (stings of ants, bees, wasps and jellyfish, grass cuttings, millet allergy, poisoning, latex contact, eating shellfish, viper venom poisoning) and stent implantation (nickel, chromium, manganese, titanium, molybdenum, polymers), which can induce allergy, either separately or synergistically[3].

A 19 year old male presented with history of dyspnoea. Over the past 2 d, he had chest pain and the first episode of syncope and was admitted to hospital. On physical examination, he was sweaty but hemodynamically stable. He had no family history of coronary artery disease. Electrocardiography (ECG) showed ventricular tachycardia (VT). On arrival, his Troponin-T was elevated (0.26 ng/mL, reference range: 0-0.03 ng/mL). A diagnosis of non-ST segment myocardial infarction with complete heart block was made. Cardiac catheterization demonstrated 99% lesion in mid right coronary artery (RCA). The ejection fraction was 60%. The percutaneous coronary intervention was performed via the right femoral artery access route. A sirolimus-eluting stent (3.5 mm × 23 mm) was deployed with an excellent angiographic result. The patient was discharged on the fifth day.

Two months later, the patient was again hospitalized with a second episode of syncope arrest and chest pain. In the brain magnetic resonance image, no significant focal intracranial abnormality was detected. An absolute eosinophil count was 645 cumm/μL (reference range: 40-440 cumm/μL). Check angiogram revealed a well flowing RCA stent with 40% de novo lesion. The remaining coronary arteries were normal. The patient was recommended for medical management and was discharged on the seventh day.

Five months later, the patient had a 3rd episode of syncope, and hence was rehospitalized for clinical evaluation with twenty-four hour electrocardiographic (Holter) monitoring, which was normal. At this time, ECG and echocardiography were normal. Patient developed VT during hospitalization which was reverted with direct current shock and beta blockers were started. During the hospital stay, on the 3rd day, the patient had chest pain again. Troponin-I was positive. A 12-lead electrocardiogram showed ST elevation in anterior leads, suggestive of hyper acute stage of anterior wall myocardial infarction. The patient was transferred to the intensive cardiac care unit and there the ST elevation disappeared. Echocardiography showed mid apical septum and apex hypokinesia. Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors were given.

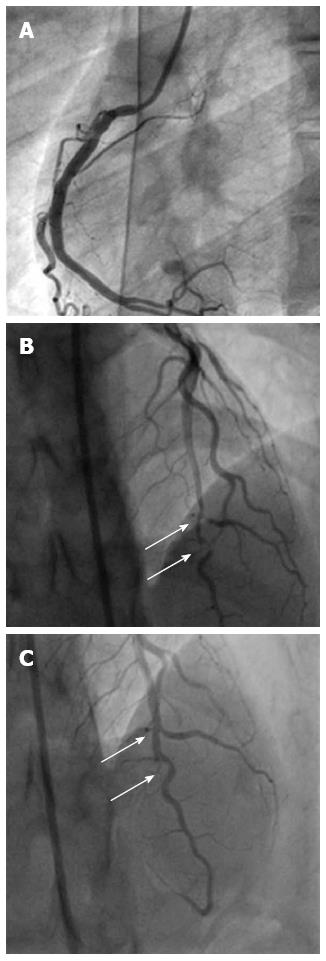

When the fourth check angiography was done, it revealed a mid to distal left anterior descending (LAD) 90% discrete lesion with sluggish flow and a well flowing RCA stent. The patient was taken for percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) to LAD after 3 d. During coronary angiography, prior to PTCA, another 80% lesion proximal to previous 90% lesion was revealed where previously no plaque was present. After repeated administered nicorandil and nitrates, both lesions became insignificant. Hence, we suspect it might due to coronary spasm. The patient was discharged under treatment with oral nicorandil, nitrates, diltiazem and antiplatelets. Beta blockers were omitted (Figure 1).

After discharge, patient had difficulty in breathing due to some nasal obstruction, so an Ear Nose and Throat (ENT) surgeon consultation was done. Subsequently, a nasal ethmoidal polyp was detected by the ENT surgeon on the basis of a computed tomography scan. The chest physician’s opinion was taken and pulmonary function tests were done, which were suggestive of mild obstructive lung disease. Bilateral functional endoscopic sinus surgery was also done (3.5 cm × 2.5 cm, reference range: 0.2 cm × 0.2 cm up to 1.4 cm × 0.8 cm). The histopathological examination of polyps was suggestive of inflammatory nasal polyps. An immunoglobulin E level was 396 kU/L (reference range: 20-100 kU/L). Normal range for all allergens is less than 0.35 U/L. Within food, cucumber 1.70 U/L, wheat 2.00 U/L, groundnut 1.80 U/L and yeast 1.60 U/L induce mid high allergy. Within inhalants, house dust 1.90 U/L, dog dander 1.10 U/L and paper dust 1.10 U/L induce mid high allergy, while house dust mite 3.50 U/L induces high allergy. Within contact, perfume 1.40 U/L induces mid high allergy. Within drugs, ciprofloxacin 1.70 U/L, cloxacillin 1.30 U/L and diclofenac 1.10 U/L induce mid high allergy, while oxacillin 0.90 U/L, tetracycline 0.60 U/L and norfloxacin 0.80 U/L induce mild allergy. During allergic screening tests (by immune-enzyme immune assay), it was found that the patient was allergic to contact, drugs, food and inhalants. The patient was advised to avoid these allergens and put on topical steroids, cetrizine and montelukast. Aspirin was omitted. To date, the patient has been doing well for the last 9 mo.

Today, allergic angina and allergic myocardial infarction are referred as “Kounis syndrome”. Aspirin-induced asthma was first described by Widal et al in 1922 and later by Samter et al[4] in 1967. The term Samter’s triad (asthma, aspirin sensitivity and nasal polyps) became popular. The Samter-Beer triad generally starts as chronic rhinitis with development of nasal polyposis. Salicylate intolerance and asthma develop over 1 to 5 years[5].

When there is a young individual with no predisposing factors of atherosclerosis and apparent coronary lesion, with or without ECG and biochemical markers of infarction, the possibility of Kounis syndrome should be kept in mind. In such situations, intracoronary vasodilators, nitrates, nicorandil or diltiazem should be used before proceeding with a coronary intervention. An urgent eosinophil count should be done before proceeding with coronary interventions to rule out coronary spasm.

P- Reviewer Kounis NG S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Yanagawa Y, Nishi K, Tomiharu N, Kawaguchi T. A case of takotsubo cardiomyopathy associated with Kounis syndrome. Int J Cardiol. 2009;132:e65-e67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kounis GN, Kounis SA, Hahalis G, Kounis NG. Coronary artery spasm associated with eosinophilia: another manifestation of Kounis syndrome? Heart Lung Circ. 2009;18:163-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chen JP, Hou D, Pendyala L, Goudevenos JA, Kounis NG. Drug-eluting stent thrombosis: the Kounis hypersensitivity-associated acute coronary syndrome revisited. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:583-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Samter M, Beers RF. Concerning the nature of intolerance to aspirin. J Allergy. 1967;40:281-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Szczeklik A, Nizankowska E, Duplaga M. Natural history of aspirin-induced asthma. AIANE Investigators. European Network on Aspirin-Induced Asthma. Eur Respir J. 2000;16:432-436. [PubMed] |