Published online Nov 15, 2018. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v9.i11.190

Peer-review started: July 30, 2018

First decision: August 27, 2018

Revised: September 15, 2018

Accepted: October 11, 2018

Article in press: October 11, 2018

Published online: November 15, 2018

Traditionally, breakfast skipping (BS), and recently late-night dinner eating (LNDE), have attracted attention in public health because they can predispose to cardiometabolic conditions such as obesity and type 2 diabetes. Intriguingly, it has become evident that short duration of sleep elicits similar health risks. As LNDE, BS, and short sleep can be closely related and can aggravate each other, these three should not be considered separately. In this context, LNDE (or its equivalents, snacking or heavy alcohol consumption after dinner) and BS may be representative unhealthy eating habits around sleep (UEHAS). While it is important to take energy in the early morning for physical and intellectual activities, attaining a fasting state is essential for metabolic homeostasis. Our previous UEHAS studies have shown that BS without LNDE, i.e., BS alone, is not associated with obesity and diabetes, suggesting the possibility that BS or taking a very low energy breakfast, which could yield fasting for a while, may prevent obesity and diabetes in people with inevitable LNDE. Further studies considering UEHAS and short sleep simultaneously are needed to elucidate the effects of these unhealthy lifestyles on cardiometabolic diseases.

Core tip: Breakfast skipping (BS), late-night dinner eating (LNDE), and short duration of sleep have attracted attention because they elicit similar health risks: Obesity and type 2 diabetes. However, to-date these factors have been considered separately in terms of their health risks. LNDE and BS may be representative unhealthy eating habits around sleep (UEHAS). It is important to take energy in the early morning, whereas attaining a fasting state is essential for metabolic homeostasis. Therefore, BS or taking a very low energy breakfast may prevent obesity and diabetes in people with LNDE. Consideration of UEHAS and short sleep deserves further study.

- Citation: Nakajima K. Unhealthy eating habits around sleep and sleep duration: To eat or fast? World J Diabetes 2018; 9(11): 190-194

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v9/i11/190.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v9.i11.190

Traditionally, breakfast skipping (BS) has been considered to contribute to various cardiometabolic conditions including obesity and type 2 diabetes not only in children and adolescents, but also in adults including the elderly[1-5]. However, conflicting results have been reported[6-8], probably because definitions of breakfast and BS have not been established yet[9,10]. Multiple confounding factors, including age, sex, morbidities, and dietary culture, may also affect the outcomes, although these confounders are usually statistically adjusted for. Moreover, for the past decade, it has been argued that BS may result from conditions in the preceding night, such as late-night dinner eating (LNDE), eating snacks after dinner, or drinking alcohol until immediately before going to bed[11-15].

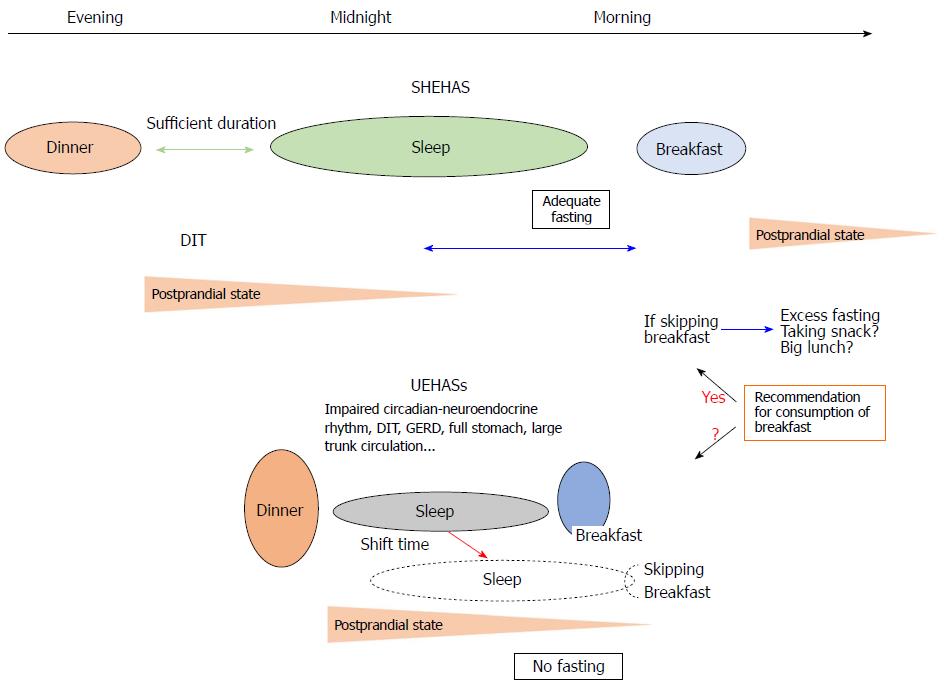

Simultaneously, the quality and quantity of sleep, which usually manifest as short or long duration of sleep, may affect conditions in the early morning such as appetite for the breakfast meal[16-19]. Of note, short duration of sleep has been robustly associated with similar cardiometabolic conditions to those associated with BS and LNDE, such as obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome, as well as increased mortality[20-23]. Taken together, the effect of short sleep on the above health risks may include the effect of BS, and vice versa. However, short sleep (or possibly long sleep) and BS have rarely been considered together. Circadian misalignment may be prevalent in individuals with LNDE, BS, and short sleep. Because LNDE, BS, and short sleep can be closely related and can aggravate each other[9,11,13,15], these three factors should not be considered separately in terms of health and cardiometabolic conditions. In this context, LNDE and BS may be representative unhealthy eating habits around sleep (UEHAS) (Figure 1). Taken together, specific features can form when UEHAS and short sleep (UEHASs) are combined because of the relationships between them, whereas sleep and UEHAS are sufficiently independent in individuals with good sleep and healthy eating-habits around sleep (SHEHAS).

It is reasonable to assume that BS prolongs the fasting state and results in a lack of energy in the morning, which can result in hampered physical and intellectual activities and possibly in larger meal consumption later in the day[9,24], though conflicting outcomes have been reported[25-28]. However, this theory may be exclusively applicable to healthy people without LNDE, i.e., those who do not take dinner late at night. Of note, LNDE may be associated with hyperglycemia[12,29-31], which remains until early morning. A time period of less than 6 h from LNDE to the end of a short sleep falls short of the 8-10 h criteria commonly used for overnight fasting[32,33], although the definition of overnight fasting has not been definitively established. Theoretically, therefore, LNDE within 2 h of going to bed combined with a short (< 6 h) sleep does not yield a fasting state in the early morning. If people with LNDE sleep for a normal length of time, the opportunity for breakfast consumption may be missed because they do not have enough time to take a breakfast meal (Figure 1).

As mentioned by numerous experts, it is important to take energy in the early morning for healthy physical activity, whereas attaining a fasting state for a certain period in the day, usually during sleep because sleep involves equal or lower energy expenditure than resting energy expenditure[34,35], is essential for metabolic homeostasis. Adequate fasting especially during sleep can enable plasma glucose to return to the preprandial level and plasma insulin to decline to baseline level, which prevents over-secretion of insulin and has a protective action for β-cell function in the pancreas. Having an appetite, i.e., a feeling of hunger, for breakfast may be inappropriate if the body is not in a fasting state (etymologically, taking a breakfast without fasting beforehand does not constitute a break of fasting). Consumption of breakfast without adequate fasting may lead to an absence of the fasting state throughout the day, which results in sustained hyperglycemia and elevated insulin secretion.

Meanwhile, in view of the time course, LNDE can affect the quantity and the quality of the following sleep[36,37], which may in turn affect the conditions of the next morning, i.e., eating breakfast. Studies concerning the effect of LNDE on sleep are limited and the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood. LNDE can deteriorate circadian rhythms and the secretion of leptin, peptide-YY, melatonin, orexins, and ghrelin[38-41]. LNDE, which can result in sleep with a full stomach, may cause gastroesophageal reflux disease[42,43] and reduced diet-induced thermogenesis[38,44], both of which reduce the quality of sleep. Additionally, higher circulation volumes consisting of a large volume of water and high concentrations of sodium and glucose in the trunk circulation may burden the heart, vessels, and kidney, possibly resulting in arrhythmia and incidents of proteinuria, as observed in our previous studies[11,45].

Shorter time periods between dinner and sleep, and between sleep and breakfast, can intensify the plausible effect of the postprandial condition after LNDE on sleep and the effect of poor sleep on breakfast, respectively (Figure 1). In addition, LNDE may affect conditions in the early morning after wakeup, especially when the duration of sleep is shorter. Therefore, it is best to refrain from LNDE for a healthy sleep and for optimal conditions in early morning. However, if it is impossible to prevent LNDE because of compulsory shift work or family/individual reasons, the dinner should have less energy and consist of a small amount of easy-to-digest ingredients. Alternatively, instead of completely skipping breakfast, consumption of a very low-calorie meal of less than 200 kcal including water, minimum minerals, and vitamins[46,47] may be an effective option for avoiding potential fasting and adverse reactions such as hypoglycemia and dehydration. Simultaneously, healthy sleep habits may be necessary for conditions the next morning.

Our previous UEHAS cross-sectional studies[11,12] have shown that BS without LNDE, i.e., BS alone, was not associated with obesity or diabetes. Therefore, these results suggest a paradoxical possibility that BS or taking a very low energy breakfast might prevent obesity and diabetes in people with habitual LNDE. Otherwise, hunger, but not fasting, occurs throughout the day in individuals with LNDE. It is possible that BS or taking a smaller breakfast in children with LNDE[13] may be a natural physiological response that manages to avoid the sustained metabolic abnormalities such as hyperglycemia caused by LNDE.

Importantly, the timing of meals substantially affects peripheral clocks existing in multiple organs, including liver, adrenal gland, stomach, intestines, pancreas, kidney, heart, and lungs[48-50]. Therefore, UEHAS may disrupt the peripheral circadian rhythm and thereby affect the central circadian rhythm, regulated by a master circadian clock located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the anterior hypothalamus, via irregular secretion of hormones including cortisol, ghrelin, leptin, insulin, glucagon, and glucagon-like peptide-1[48]. This metabolic feedback can be mediated through so-called circadian-endocrine cross-talk[49]. In particular, LNDE may enhance the desynchrony between the peripheral and central circadian rhythms, possibly by shortening the duration of sleep, besides unfavorable effects of LNDE on the secretion of incretins. Intriguingly, plasma insulin has been reported to be fundamentally regulated by pancreatic autonomous circadian oscillators, independent of the suprachiasmatic nucleus[51]. In this regard, however, the composition of a meal, for instance the proportion of energy as carbohydrate, can also affect the peripheral circadian rhythm because insulin is usually secreted in in greater quantities following a carbohydrate rich meal. This topic therefore warrants further study.

In conclusion, taking a breakfast is recommended primarily for people without LNDE to take sufficient energy for intellectual and physical activities in the morning (Figure 1). In contrast, taking a breakfast, especially of a full amount, may not be recommended for people with habitual LNDE to allow them to attain a fasting state for a certain period per day. However, a well-considered meal for late-night dinner or breakfast can ameliorate the conditions above and the metabolic abnormalities in people with LNDE and/or BS, in harmony with the autonomous circadian-endocrine system. Health professionals such as physicians and dieticians should carefully consider individuals’ backgrounds and chrono-nutrition, and UEHASs. Further integrated studies are needed to elucidate the effects of eating behaviors and sleep on health and cardiometabolic diseases in view of scientific and public interests.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Endocrinology and metabolism

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Hamasaki H, Hamaguchi M, Serhiyenko VA, Surani S, Tziomalos K S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Bian YN

| 1. | Pereira MA, Erickson E, McKee P, Schrankler K, Raatz SK, Lytle LA, Pellegrini AD. Breakfast frequency and quality may affect glycemia and appetite in adults and children. J Nutr. 2011;141:163-168. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 115] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Horikawa C, Kodama S, Yachi Y, Heianza Y, Hirasawa R, Ibe Y, Saito K, Shimano H, Yamada N, Sone H. Skipping breakfast and prevalence of overweight and obesity in Asian and Pacific regions: a meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2011;53:260-267. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 158] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bi H, Gan Y, Yang C, Chen Y, Tong X, Lu Z. Breakfast skipping and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18:3013-3019. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 109] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Otaki N, Obayashi K, Saeki K, Kitagawa M, Tone N, Kurumatani N. Relationship between Breakfast Skipping and Obesity among Elderly: Cross-Sectional Analysis of the HEIJO-KYO Study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21:501-504. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Okada C, Tabuchi T, Iso H. Association between skipping breakfast in parents and children and childhood overweight/obesity among children: a nationwide 10.5-year prospective study in Japan. Int J Obes (Lond). 2018;42:1724-1732. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | McCrory MA. Meal skipping and variables related to energy balance in adults: a brief review, with emphasis on the breakfast meal. Physiol Behav. 2014;134:51-54. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lee JS, Mishra G, Hayashi K, Watanabe E, Mori K, Kawakubo K. Combined eating behaviors and overweight: Eating quickly, late evening meals, and skipping breakfast. Eat Behav. 2016;21:84-88. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dhurandhar EJ. True, true, unrelated? A review of recent evidence for a causal influence of breakfast on obesity. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23:384-388. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zilberter T, Zilberter EY. Breakfast: to skip or not to skip? Front Public Health. 2014;2:59. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gibney MJ, Barr SI, Bellisle F, Drewnowski A, Fagt S, Livingstone B, Masset G, Varela Moreiras G, Moreno LA, Smith J. Breakfast in Human Nutrition: The International Breakfast Research Initiative. Nutrients. 2018;10:pii: E559. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 90] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kutsuma A, Nakajima K, Suwa K. Potential Association between Breakfast Skipping and Concomitant Late-Night-Dinner Eating with Metabolic Syndrome and Proteinuria in the Japanese Population. Scientifica (Cairo). 2014;2014:253581. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 81] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nakajima K, Suwa K. Association of hyperglycemia in a general Japanese population with late-night-dinner eating alone, but not breakfast skipping alone. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2015;14:16. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Karatzi K, Moschonis G, Choupi E, Manios Y; Healthy Growth Study group. Late-night overeating is associated with smaller breakfast, breakfast skipping, and obesity in children: The Healthy Growth Study. Nutrition. 2017;33:141-144. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Teixeira GP, Mota MC, Crispim CA. Eveningness is associated with skipping breakfast and poor nutritional intake in Brazilian undergraduate students. Chronobiol Int. 2018;35:358-367. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Azami Y, Funakoshi M, Matsumoto H, Ikota A, Ito K, Okimoto H, Shimizu N, Tsujimura F, Fukuda H, Miyagi C. Long working hours and skipping breakfast concomitant with late evening meals are associated with suboptimal glycemic control among young male Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Investig. 2018;. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pot GK. Sleep and dietary habits in the urban environment: the role of chrono-nutrition. Proc Nutr Soc. 2018;77:189-198. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 70] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chaput JP, Dutil C. Lack of sleep as a contributor to obesity in adolescents: impacts on eating and activity behaviors. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:103. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 127] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Li W, Sekine M, Yamada M, Fujimura Y, Tatsuse T. Lifestyle and overall health in high school children: Results from the Toyama birth cohort study, Japan. Pediatr Int. 2018;60:467-473. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ogilvie RP, Lutsey PL, Widome R, Laska MN, Larson N, Neumark-Sztainer D. Sleep indices and eating behaviours in young adults: findings from Project EAT. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21:689-701. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Xi B, He D, Zhang M, Xue J, Zhou D. Short sleep duration predicts risk of metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18:293-297. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 168] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dashti HS, Scheer FA, Jacques PF, Lamon-Fava S, Ordovás JM. Short sleep duration and dietary intake: epidemiologic evidence, mechanisms, and health implications. Adv Nutr. 2015;6:648-659. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 292] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wu Y, Gong Q, Zou Z, Li H, Zhang X. Short sleep duration and obesity among children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2017;11:140-150. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Medic G, Wille M, Hemels ME. Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nat Sci Sleep. 2017;9:151-161. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 580] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 641] [Article Influence: 91.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Betts JA, Chowdhury EA, Gonzalez JT, Richardson JD, Tsintzas K, Thompson D. Is breakfast the most important meal of the day? Proc Nutr Soc. 2016;75:464-474. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Iovino I, Stuff J, Liu Y, Brewton C, Dovi A, Kleinman R, Nicklas T. Breakfast consumption has no effect on neuropsychological functioning in children: a repeated-measures clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104:715-721. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chowdhury EA, Richardson JD, Tsintzas K, Thompson D, Betts JA. Effect of extended morning fasting upon ad libitum lunch intake and associated metabolic and hormonal responses in obese adults. Int J Obes (Lond). 2016;40:305-311. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zakrzewski-Fruer JK, Plekhanova T, Mandila D, Lekatis Y, Tolfrey K. Effect of breakfast omission and consumption on energy intake and physical activity in adolescent girls: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Nutr. 2017;118:392-400. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yoshimura E, Hatamoto Y, Yonekura S, Tanaka H. Skipping breakfast reduces energy intake and physical activity in healthy women who are habitual breakfast eaters: A randomized crossover trial. Physiol Behav. 2017;174:89-94. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sato M, Nakamura K, Ogata H, Miyashita A, Nagasaka S, Omi N, Yamaguchi S, Hibi M, Umeda T, Nakaji S. Acute effect of late evening meal on diurnal variation of blood glucose and energy metabolism. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2011;5:e169-e266. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sakai R, Hashimoto Y, Ushigome E, Miki A, Okamura T, Matsugasumi M, Fukuda T, Majima S, Matsumoto S, Senmaru T. Late-night-dinner is associated with poor glycemic control in people with type 2 diabetes: The KAMOGAWA-DM cohort study. Endocr J. 2018;65:395-402. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kadowaki T, Haneda M, Ito H, Sasaki K, Hiraide S, Matsukawa M, Ueno M. Relationship of Eating Patterns and Metabolic Parameters, and Teneligliptin Treatment: Interim Results from Post-marketing Surveillance in Japanese Type 2 Diabetes Patients. Adv Ther. 2018;35:817-831. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Mayer KH, Stamler J, Dyer A, Freinkel N, Stamler R, Berkson DM, Farber B. Epidemiologic findings on the relationship of time of day and time since last meal to glucose tolerance. Diabetes. 1976;25:936-943. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Pongsuthana S, Tivatunsakul N. Optimal Fasting Time before Measurement of Serum Triglyceride Levels in Healthy Volunteers. J Med Assoc Thai. 2016;99 Suppl 2:S42-S46. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Garby L, Kurzer MS, Lammert O, Nielsen E. Energy expenditure during sleep in men and women: evaporative and sensible heat losses. Hum Nutr Clin Nutr. 1987;41:225-233. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Jung CM, Melanson EL, Frydendall EJ, Perreault L, Eckel RH, Wright KP. Energy expenditure during sleep, sleep deprivation and sleep following sleep deprivation in adult humans. J Physiol. 2011;589:235-244. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 210] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Crispim CA, Zimberg IZ, dos Reis BG, Diniz RM, Tufik S, de Mello MT. Relationship between food intake and sleep pattern in healthy individuals. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7:659-664. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 101] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Brown RF, Thorsteinsson EB, Smithson M, Birmingham CL, Aljarallah H, Nolan C. Can body temperature dysregulation explain the co-occurrence between overweight/obesity, sleep impairment, late-night eating, and a sedentary lifestyle? Eat Weight Disord. 2017;22:599-608. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | McHill AW, Melanson EL, Higgins J, Connick E, Moehlman TM, Stothard ER, Wright KP Jr. Impact of circadian misalignment on energy metabolism during simulated nightshift work. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:17302-17307. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 217] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Gallant A, Lundgren J, Drapeau V. Nutritional Aspects of Late Eating and Night Eating. Curr Obes Rep. 2014;3:101-107. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Medic G, Korchagina D, Young KE, Toumi M, Postma MJ, Wille M, Hemels M. Do payers value rarity? An analysis of the relationship between disease rarity and orphan drug prices in Europe. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2017;5:1299665. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Sieminski M, Szypenbejl J, Partinen E. Orexins, Sleep, and Blood Pressure. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20:79. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Fujiwara Y, Arakawa T, Fass R. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and sleep disturbances. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:760-769. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 67] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Takeshita E, Furukawa S, Sakai T, Niiya T, Miyaoka H, Miyake T, Yamamoto S, Senba H, Yamamoto Y, Arimitsu E. Eating Behaviours and Prevalence of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Japanese Adult Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: The Dogo Study. Can J Diabetes. 2018;42:308-312. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Romon M, Edme JL, Boulenguez C, Lescroart JL, Frimat P. Circadian variation of diet-induced thermogenesis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;57:476-480. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 136] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Nakajima K, Suwa K, Oda E. Atrial fibrillation may be prevalent in individuals who report late-night dinner eating and concomitant breakfast skipping, a complex abnormal eating behavior around sleep. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177:1124-1126. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Anderson JW, Hamilton CC, Brinkman-Kaplan V. Benefits and risks of an intensive very-low-calorie diet program for severe obesity. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:6-15. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 47. | Johansson K, Neovius M, Hemmingsson E. Effects of anti-obesity drugs, diet, and exercise on weight-loss maintenance after a very-low-calorie diet or low-calorie diet: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:14-23. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 148] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Patton DF, Mistlberger RE. Circadian adaptations to meal timing: neuroendocrine mechanisms. Front Neurosci. 2013;7:185. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 113] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Tsang AH, Astiz M, Friedrichs M, Oster H. Endocrine regulation of circadian physiology. J Endocrinol. 2016;230:R1-R11. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Jiang P, Turek FW. Timing of meals: when is as critical as what and how much. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2017;312:E369-E380. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 49] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Damiola F, Le Minh N, Preitner N, Kornmann B, Fleury-Olela F, Schibler U. Restricted feeding uncouples circadian oscillators in peripheral tissues from the central pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2950-2961. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1680] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1645] [Article Influence: 68.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |