Published online Sep 15, 2014. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v6.i9.351

Revised: October 21, 2013

Accepted: December 17, 2013

Published online: September 15, 2014

Processing time: 401 Days and 10.4 Hours

Pancreatic cancer, with a 5% 5-year survival rate, is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in Western countries. Unfortunately, only 20% of all patients benefit from surgical treatment. The need to prolong survival has prompted pathologists to develop improved protocols to evaluate pancreatic specimens and their surgical margins. Hopefully, the new protocols will provide clinicians with more powerful prognostic indicators and accurate information to guide their therapeutic decisions. Despite the availability of several guidelines for the handling and pathology reporting of duodenopancreatectomy specimens and their continual updating by expert pathologists, there is no consensus on basic issues such as surgical margins or the definition of incomplete excision (R1) of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. This article reviews the problems and controversies that dealing with duodenopancreatectomy specimens pose to pathologists, the various terms used to define resection margins or infiltration, and reports. After reviewing the literature, including previous guidelines and based on our own experience, we present our protocol for the pathology handling of duodenopancreatectomy specimens.

Core tip: Pancreatic cancer, one of the most lethal tumor types, is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in developed countries. The need to prolong patient survival has prompted the development of improved protocols to evaluate duodenopancreatectomy specimens and their surgical margins by pathologists. Despite the availability of several guidelines and their continual updating, there is no consensus on basic issues such as surgical margins or the definition of incomplete excision. We herein review the controversies and approaches in the literature and present our own protocol for the handling and reporting of pancreatoduodenectomy specimens by pathologists.

- Citation: Gómez-Mateo MDC, Sabater-Ortí L, Ferrández-Izquierdo A. Pathology handling of pancreatoduodenectomy specimens: Approaches and controversies. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2014; 6(9): 351-359

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v6/i9/351.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v6.i9.351

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the most common cancer affecting the exocrine pancreas and the fourth leading cause of cancer death in both sexes in the United States[1]. In that country, pancreatic cancer accounts for 3% of all new malignancies. It is estimated that 45220 new cases will be diagnosed there during 2013 and it will be the cause of death for 38460 patients[1]. Death rates for pancreatic cancer between 2005 and 2009 were 12.5 and 9.5 per 100000 inhabitants (males and females, respectively)[1]. In Europe, pancreatic cancer accounted for 6.2% of deaths in 2012 (78000 patients)[2]. The overall 5 year survival rate remains dismal, at around 5%[1].

Unfortunately, only 8% of pancreatic cancer patients are diagnosed in the early stages and of those, only 20% are susceptible to surgical treatment[3].

The clinical management of oncological patients relies on robust pathological data for the assessment of the extent of the disease. Despite general guidelines for the handling and pathology reporting of pancreatic specimens which are constantly updated by expert pancreatic pathologists, there is no consensus in basic terms as to what margins of surgically resected PDAC must be reported or what exactly defines an incomplete excision (R1)[4]. In this report, we review these differences in the current literature and present the protocol that is used in our institutions, based on a European trend.

One of the most important steps in pathology reporting is the dissection procedure. There is a lack of consensus, however, in the development of a standardized guide for the macroscopic management of PDAC specimens. This is perhaps due to the fact that pancreatic surgery is not performed in all hospitals so not all pathologists have access to these pathologies. In addition, the precise evaluation of resection margins has been considered less critical due to the poor prognosis of this neoplasm and its lack of response to standard chemotherapy[5].

Despite the fact that resection margin status is a key prognostic factor, the rates of microscopic margin involvement (R1) vary enormously from study to study[6-10]. The disparities may be a result of differences as to what constitutes a resection margin, the controversy over the definition of R1 status and the lack of a standardized dissection protocol of PDAC specimens[5]. In recent studies[5,11,12], an important increase in R1 resections has been reported after the use of a standardized protocol of pathological reporting of PDAC specimens. An example is given in the study by Esposito et al[11] in which they show a change from 14% R1 resections to 76% when a standardized protocol was applied. Other series, including our preliminary report of 2007[13], have similar changes[5,11,14].

Four relevant margins should be studied in PDAC: (1) luminal margins (proximal gastric or duodenal and distal jejunal); (2) bile duct margin (BDM), common bile duct or common hepatic duct margin; (3) pancreatic transection margin (PTM); and (4) pancreatic circumferential or radial margin (CRM).

The first three margins are universally accepted and easily recognizable in the specimen. In addition, the BDM and PTM can be examined intraoperatively.

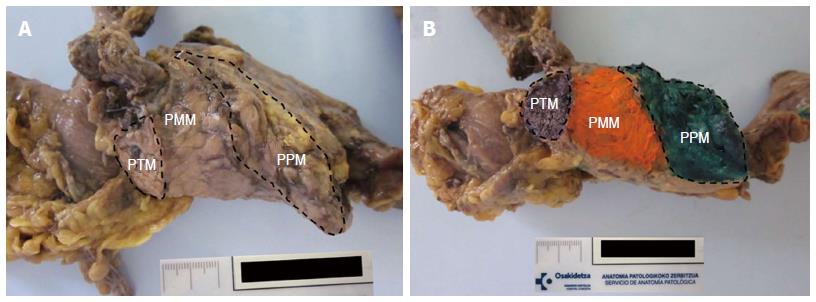

According to Verbeke’s reports, the CRM can be divided anatomically into an anterior surface or pancreatic anterior margin (PAM) and a posterior surface or pancreatic posterior margin (PPM). They are separated by a pancreatic medial margin (PMM), the part of the surface of the pancreatic head that faces the superior mesenteric (SM) vessels[5,15].

The PAM cannot be considered a true margin since there is no transection by the surgeon at this level. Although the PPM and PMM are truly the most important margins since they are frequently affected[5,12,13,16], we cannot ignore the fact that the presence of tumor cells on the anterior surface is likely to increase the risk of local tumor recurrence[5,17].

The PMM refers to the area that faces the superior mesenteric vessels, totally or partially surrounding the superior mesenteric vein. It has a shallow groove-like shape and a slightly glistening surface flanked by ties. Segments of vessels can be found when involved in the cancer[5]. The PMM is the margin most frequently involved and therefore requires careful assessment[15,18-20]. The PMM has many names, such as “vascular bed”, “uncinated process margin”, “mesenteric margin” or even “retroperitoneal margin”. The last denomination may cause confusion[5,13,16] given that the entire head of the pancreas and not just this surface is located in the retroperitoneum.

The PPM is the area adjacent to the superior mesenteric artery the surgeon transects so it is a true margin[5].

In a recent publication by Khalifa et al[16], the nomenclature commonly used for pancreatic margins is reviewed. It makes evident the great variability, especially that in relationship to the circumferential margin, and the need for consensus. The terms “posterior” and “medial” margins are commonly used by European pathologists[11,16,21], while “deep retroperitoneal posterior surface” or “uncinated process” margins are the terms chosen by the College of American Pathologists (CAP) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)[22-24] (Figure 1).

A wide range of different dissection techniques are used given the lack of consensus. Many of them are based on tradition rather than on an evidence-based rationale[5].

For many years, the longitudinal opening of the main pancreatic and biliary duct has been the standard technique used by European and American pathologists[15,18-21,25-27]. This method, however, interferes with the CRM assessment and is uninformative since the majority of PDAC do not arise in the main duct, with the exception of the intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm[5].

In some classic American protocols, there is no specified procedure for the specimen dissection[28] and the need to ink some of the margins and submit them is only superficially addressed[19,22,23,29].

Methods based on sections parallel to the pancreatic major axis, including a longitudinal section of the duodenal wall, have been used in Europe for many years[25]. The resulting sections are too thick and comprise different planes, something which makes it difficult for the pathologist to reconstruct the specimen or assess tumor size and margin status[5].

Both the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) in its 3rd edition[27] and Allen and Cameron in 2004[30] suggested a way of handling specimens based on the opening of biliary and pancreatic ducts with sections perpendicular to the ducts. Recently, in their 4th edition, the AFIP[31] recommended performing perpendicular sections to the main duct. That notwithstanding, these sections would be tangential to the duodenal wall, thus making the analysis of the ampulla, distal pancreatic and bile duct difficult[5].

The Japan Pancreas Society[32] has suggested slicing perpendicular to an axis that follows the curvature of the pancreatic head, even although the constant change of planes is an inconvenience[5].

The procedure performed by Westgaard et al[12] consists of inking the retroperitoneal margin, performing a 5-10 mm thick section parallel to this margin and serially slicing perpendicular to the ink.

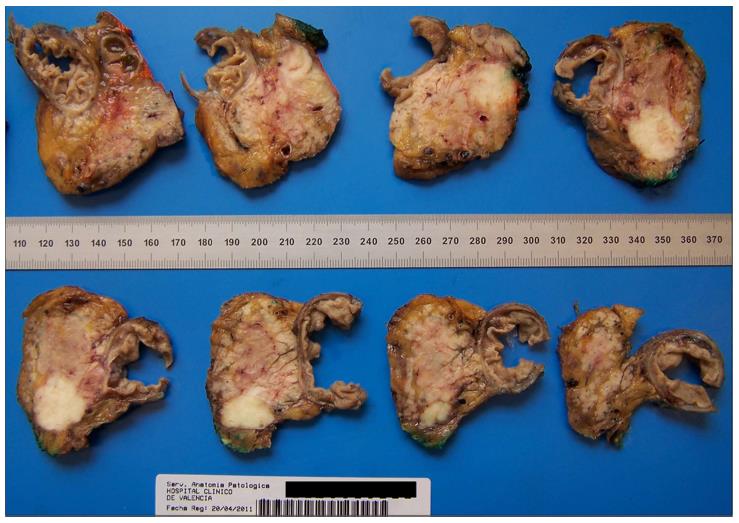

In the last few years, a new standardized dissection technique[5,11,15,33] has been developed in Europe, especially in the United Kingdom. It is characterized by a serial slicing of the entire pancreatic head in a plane perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the duodenum which avoids opening the biliary or pancreatic duct (Figure 2). The advantage of this method is its simplicity. There is no dependency of location or nature of the disease and a great number of sections are produced. This permits an extensive study of the lesion and its relationship with anatomical structures and surgical margins[5,15].

The AJCC and CAP protocols recommend inking and cutting sections through the tumor at its closest approach to the retroperitoneal margin of the uncinate process (uncinate margin) and retroperitoneal posterior surface[22,23].

Only Allen and Cameron[30] recommend the need for analyzing the following margins in their book: superior, inferior, capsular anterior, posterior retroperitoneal and medial (superior mesenteric vein).

The Royal College of Pathologists[21] includes the transection margins (gastric, duodenum, pancreatic and common bile) and the dissected margins (superior mesenteric vessels and medial and posterior margins) in their histopathological report.

The anterior surface of the pancreas is not a true surgical margin but invasion of this surface has been associated with local relapse and decreased survival times[17,34]. For this reason, some authors and guides suggest reporting this margin[5,11,21,31], although it is not reported by the CAP[22] or by the 7th edition of the AJCC[23].

The lack of consensus on margins not only affects their nomenclature and inclusion in the pathological report, but also the definition of R1.

The role of margin involvement and its prognostic relevance has been well characterized in other cancer types, such as rectal cancer. Verbeke, though, states that “margin status in pancreatic cancer has been neglected”[5].

Resection margin involvement (R1) seems to be an important prognostic factor in pancreatic cancer but R1 rates reported in the literature vary enormously. Rates as disparate as 16% and > 75% have been reported in different studies and consequently clinical outcome correlation has been observed in some but not all[5,6,15,35].

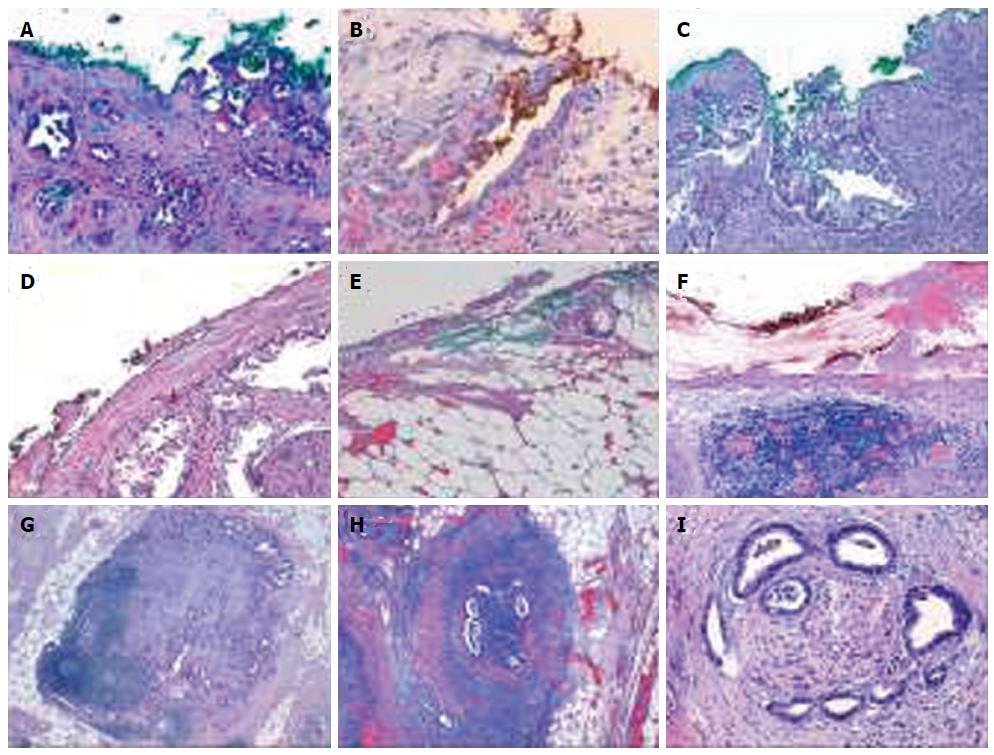

For the majority of American pathologists, there is a positive margin (R1) only when the tumor is directly in contact with the inked margin (0 mm clearance)[13,16,22,31,35]. For European pathologists, R1 margin involvement is established when the distance between the tumor and the resection margin is 1 mm or less[5,11,12,15,21]. This is called the “1 mm rule” and was taken from the R1 definition of rectal cancer assessment[21].

Another confusing circumstance is when there is no direct margin involvement by the tumor. Despite the absence of clear evidence, The Royal College of Pathologists suggests considering the incomplete excision to be an R1 resection if lymph node metastases or perineural/lymphovascular invasion is within the 1 mm limit (indirect invasion of R1)[5,11,21]. Conversely, according to the tumor-node-metastasis staging system of the AJCC, the resection margin is considered R1 indirectly only when tumor cells are attached to or invade the vessel wall[36] (Figure 3).

Lymph node metastases (N1) have been shown to be an independent negative prognostic factor in multivariate analysis[10,37-41]. Nevertheless, the lymph node ratio, defined as the ratio of the number of positive lymph nodes to the total number of lymph nodes evaluated, is now considered a more powerful prognostic marker than the overall nodal status in resected pancreatic cancer[10,13,42-48].

In the 5th edition of the AJCC[49], N1 was subdivided into 2 categories, N1a and N1b, depending on the number of lymph nodes affected (3 or less for N1a and more than 3 for N1b). In the subsequent versions (6th and 7th), this subdivision was changed. They considered N1 to be lymphatic metastases no matter how many lymph nodes were involved[23,29,49]. The following lymph nodes were considered to be regional: hepatic artery nodes, superior mesenteric artery nodes, retroperitoneal and lateral aortic nodes, infrapyloric and subpyloric nodes for tumors in the head; and celiac, pancreaticolieno and splenic nodes for tumors arising in the body and tail[22]. Tumor involvement of other nodal groups is considered distant metastasis[50]. In the Japan Pancreas Society, lymph node stations are classified into groups designated by numbers[32].

According to the CAP, the optimal histological examination should include a minimum of 15 lymph nodes[22,40]. This number is an indicator of the quality of the surgical procedure and pathological handling.

Direct extension of the primary tumor into lymph nodes is classified as lymph node metastasis[22,51].

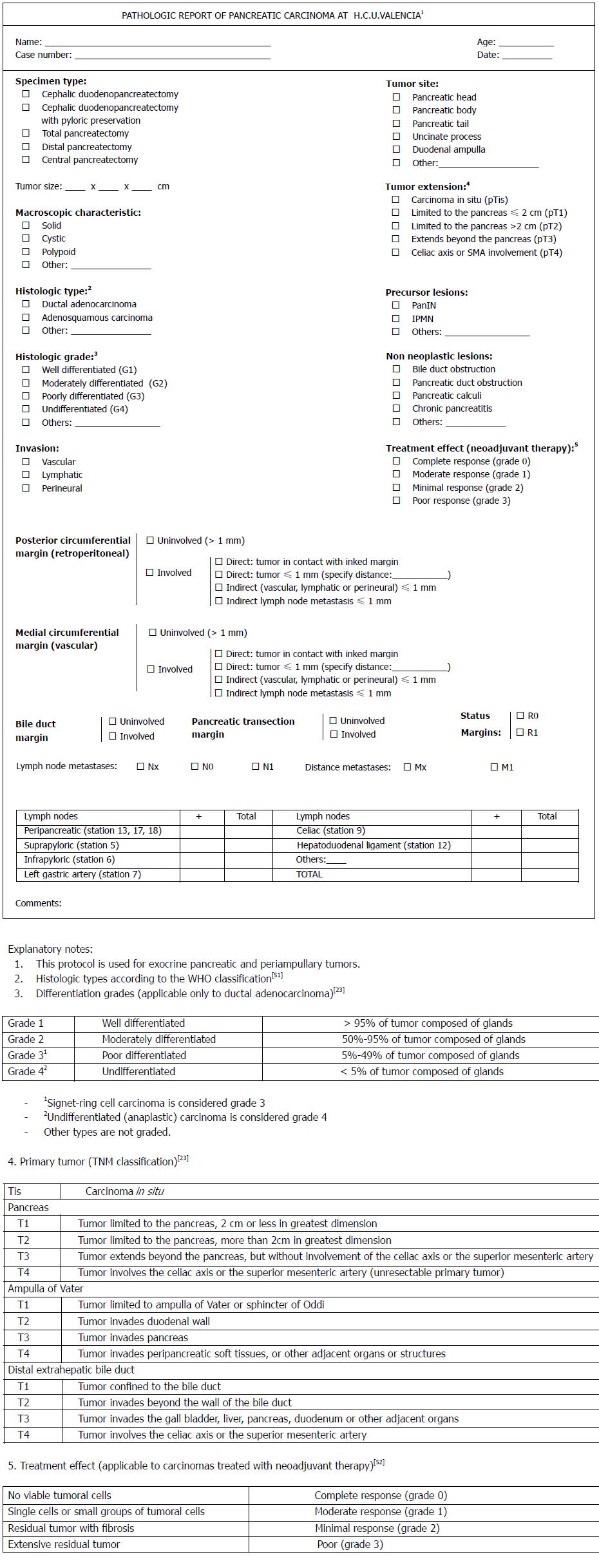

Following the published reports and guidelines, we have elaborated on a checklist for the pathological reporting of PDAC at our institution[53] based on the Verbeke reports (Figure 4).

We propose the following steps for the dissection protocol: (1) leave the specimen for 24-48 h in formaldehyde for the correct fixation after opening through the antimesenteric border of the duodenum; (2) explore the pancreatic anatomy in order to identify the different parts (head, body and tail) and give it the correct orientation in readiness for dissection. Identify the margins (circumferential resection margin composed of the PAM, PPM and PMM and the pancreatic transection margin, or PTM); (3) ink the margins indicated in step 2 in different colors; (4) slice the luminal margins (proximal gastric or duodenal and distal jejunal), BDM, common bile duct or common hepatic duct margin and PTM; (5) analyze the gastro-intestinal lumen to identify any ampullary or other lesions; (6) following the European guidelines, slice the entire pancreatic head in a plane perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the duodenum through the center of the ampulla. Identify the tumor, its size and relationships to structures and its distance to the margins; (7) continue slicing in parallel sections with a thickness of 5 mm in order to have samples of the tumor that show its relationship with the different anatomical structures (duodenum wall, ampulla) and inked resection margins; (8) separate a sample of non-neoplastic pancreas; and (9) identify lymph nodes from the different stations for individual analysis.

P- Reviewer: Keck T, Singh PK, Singh S S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9215] [Cited by in RCA: 9855] [Article Influence: 821.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, Rosso S, Coebergh JW, Comber H, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1374-1403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3526] [Cited by in RCA: 3652] [Article Influence: 304.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Ghaneh P, Costello E, Neoptolemos JP. Biology and management of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2007;56:1134-1152. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Esposito I, Born D. Pathological reporting and staging following pancreatic cancer resection. In Neoptolemos JP, Urrutia R, Abbruzzese JL, Büchler MW. Pancreatic cancer Volume 2. New York Springer. 2010;2010:1016-1030. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Verbeke CS. Resection margins and R1 rates in pancreatic cancer--are we there yet? Histopathology. 2008;52:787-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Benassai G, Mastrorilli M, Quarto G, Cappiello A, Giani U, Forestieri P, Mazzeo F. Factors influencing survival after resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas. J Surg Oncol. 2000;73:212-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jarufe NP, Coldham C, Mayer AD, Mirza DF, Buckels JA, Bramhall SR. Favourable prognostic factors in a large UK experience of adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas and periampullary region. Dig Surg. 2004;21:202-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Han SS, Jang JY, Kim SW, Kim WH, Lee KU, Park YH. Analysis of long-term survivors after surgical resection for pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2006;32:271-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Moon HJ, An JY, Heo JS, Choi SH, Joh JW, Kim YI. Predicting survival after surgical resection for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Pancreas. 2006;32:37-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sierzega M, Popiela T, Kulig J, Nowak K. The ratio of metastatic/resected lymph nodes is an independent prognostic factor in patients with node-positive pancreatic head cancer. Pancreas. 2006;33:240-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Esposito I, Kleeff J, Bergmann F, Reiser C, Herpel E, Friess H, Schirmacher P, Büchler MW. Most pancreatic cancer resections are R1 resections. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1651-1660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 454] [Cited by in RCA: 561] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Westgaard A, Tafjord S, Farstad IN, Cvancarova M, Eide TJ, Mathisen O, Clausen OP, Gladhaug IP. Resectable adenocarcinomas in the pancreatic head: the retroperitoneal resection margin is an independent prognostic factor. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cánovas R, Sabater L, Ferrández A, Calvete J, Sala C, Aparisi L, Terrádez B, Camps B, Sastre J, Lledó S. Implicaciones pronósticas del estudio estandarizado de los márgenes de resección en el cáncer de páncreas. Cir Esp. 2007;82 Suppl 1:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Katz MHG, Hwang R, Fleming JB, Evans DG. Tumor-Node-Metastasis Staging of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:111-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Verbeke CS, Leitch D, Menon KV, McMahon MJ, Guillou PJ, Anthoney A. Redefining the R1 resection in pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2006;93:1232-1237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 419] [Cited by in RCA: 444] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Khalifa MA, Maksymov V, Rowsell C. Retroperitoneal margin of the pancreaticoduodenectomy specimen: anatomic mapping for the surgical pathologist. Virchows Arch. 2009;454:125-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nagakawa T, Nagamori M, Futakami F, Tsukioka Y, Kayahara M, Ohta T, Ueno K, Miyazaki I. Results of extensive surgery for pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer. 1996;77:640-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Compton CC, Henson DE. Protocol for the examination of specimens removed from patients with carcinoma of the exocrine pancreas: a basis for checklists. Cancer Committee, College of American Pathologists. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1997;121:1129-1136. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Lüttges J, Vogel I, Menke M, Henne-Bruns D, Kremer B, Klöppel G. The retroperitoneal resection margin and vessel involvement are important factors determining survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas. Virchows Arch. 1998;433:237-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chatelain D, Fléjou JF. Pancreatectomy for adenocarcinoma: prognostic factors, recommendations for pathological reports. Ann Pathol. 2002;22:422-431. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Campbell F, Foulis AK, Verbeke CS. The Royal College of Pathologists. Standards and minimum datasets for reporting cancers. Minimum dataset for histopathological reporting of pancreatic, ampulla of Vater and bile duct carcinoma (www.rcpath.org). London: The Royal College of Pathologists 2010; . |

| 22. | Washington K, Berlin J, Branton P, Burgart LJ, Carter DK, Fitzgibbons P, Frankel WL, Jessup J, Kakar S, Minsky B. Protocol for the Examination of Specimens From Patients With Carcinoma of the Exocrine Pancreas (www.cap.org). IL: College of American Pathologists 2012; . |

| 23. | Edge SB, Byrd DR, Carducci MA, Compton CC. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer 2009; . |

| 24. | Greene FL, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Shah JP, Winchester DP. AJCC Cancer Staging Atlas. New York, NY: Springer 2006; . [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | Lüttges J, Zamboni G, Klöppel G. Recommendation for the examination of pancreaticoduodenectomy specimens removed from patients with carcinoma of the exocrine pancreas. A proposal for a standardized pathological staging of pancreaticoduodenectomy specimens including a checklist. Dig Surg. 1999;16:291-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Willett CG, Lewandrowski K, Warshaw AL, Efird J, Compton CC. Resection margins in carcinoma of the head of the pancreas. Implications for radiation therapy. Ann Surg. 1993;217:144-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Solcia E, Capella C and Klöppel G. Tumors of the pancreas. AFIP Atlas of Tumor Pathology, 3rd series, fascicle 20. Washington, DC: Armed Force Institute of Pathology 1997; . |

| 28. | Albores-Saavedra J, Heffess C, Hruban RH, Klimstra D, Longnecker D. Recommendations for the reporting of pancreatic specimens containing malignant tumors. The Association of Directors of Anatomic and Surgical Pathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;111:304-307. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, Fritz AG, Balch CM, Haller DG, Marrow M. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th ed. Chicago: Springer 2002; . [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 30. | Allen DC, Cameron RI. Histopathology Specimens. Clinical Pathological and Laboratory Aspects. London: Springer-Verlag 2004; 35-50. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 31. | Hruban RH, Bishop Pitman M, Klimstra DS. Tumors of the pancreas. In AFIP Atlas of Tumor Pathology, 4th series, fascicle 6. Washington, DC: Armed Force Institute of Pathology 2007; . |

| 32. | Japan Pancreas Society. Classification of Pancreatic Carcinoma (2nd ed). Tokyo: Kanehar. Washington, DC: Armed Force Institute of Pathology 2003; . |

| 33. | Westra WH, Hruban RH, Phelps TH, Isacson C. Surgical Pathology Disecction: An Illustrated Guide. 2nd ed. New York: Springer-Verlag 2003; 88–93. |

| 34. | Nagakawa T, Sanada H, Inagaki M, Sugama J, Ueno K, Konishi I, Ohta T, Kayahara M, Kitagawa H. Long-term survivors after resection of carcinoma of the head of the pancreas: significance of histologically curative resection. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2004;11:402-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Raut CP, Tseng JF, Sun CC, Wang H, Wolff RA, Crane CH, Hwang R, Vauthey JN, Abdalla EK, Lee JE. Impact of resection status on pattern of failure and survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2007;246:52-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 449] [Cited by in RCA: 446] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Wittekind C, Compton CC, Greene FL, Sobin LH. TNM residual tumor classification revisited. Cancer. 2002;94:2511-2516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 331] [Cited by in RCA: 340] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Lim JE, Chien MW, Earle CC. Prognostic factors following curative resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a population-based, linked database analysis of 396 patients. Ann Surg. 2003;237:74-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 454] [Cited by in RCA: 457] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Winter JM, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, Arnold MA, Chang DC, Coleman J, Hodgin MB, Sauter PK, Hruban RH, Riall TS. 1423 pancreaticoduodenectomies for pancreatic cancer: A single-institution experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1199-1210; discussion 1210-1211. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Shimada K, Sakamoto Y, Sano T, Kosuge T. Prognostic factors after distal pancreatectomy with extended lymphadenectomy for invasive pancreatic adenocarcinoma of the body and tail. Surgery. 2006;139:288-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Tomlinson JS, Jain S, Bentrem DJ, Sekeris EG, Maggard MA, Hines OJ, Reber HA, Ko CY. Accuracy of staging node-negative pancreas cancer: a potential quality measure. Arch Surg. 2007;142:767-723; discussion 773-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Schnelldorfer T, Ware AL, Sarr MG, Smyrk TC, Zhang L, Qin R, Gullerud RE, Donohue JH, Nagorney DM, Farnell MB. Long-term survival after pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: is cure possible? Ann Surg. 2008;247:456-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 339] [Cited by in RCA: 376] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Berger AC, Watson JC, Ross EA, Hoffman JP. The metastatic/examined lymph node ratio is an important prognostic factor after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Am Surg. 2004;70:235-240; discussion 240. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Garcea G, Dennison AR, Ong SL, Pattenden CJ, Neal CP, Sutton CD, Mann CD, Berry DP. Tumour characteristics predictive of survival following resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the head of pancreas. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:892-897. [PubMed] |

| 44. | House MG, Gönen M, Jarnagin WR, D’Angelica M, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, Brennan MF, Allen PJ. Prognostic significance of pathologic nodal status in patients with resected pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1549-1555. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Pawlik TM, Gleisner AL, Cameron JL, Winter JM, Assumpcao L, Lillemoe KD, Wolfgang C, Hruban RH, Schulick RD, Yeo CJ. Prognostic relevance of lymph node ratio following pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer. Surgery. 2007;141:610-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 334] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Slidell MB, Chang DC, Cameron JL, Wolfgang C, Herman JM, Schulick RD, Choti MA, Pawlik TM. Impact of total lymph node count and lymph node ratio on staging and survival after pancreatectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a large, population-based analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:165-174. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Hellan M, Sun CL, Artinyan A, Mojica-Manosa P, Bhatia S, Ellenhorn JD, Kim J. The impact of lymph node number on survival in patients with lymph node-negative pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2008;37:19-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Falconi M, Crippa S, Domínguez I, Barugola G, Capelli P, Marcucci S, Beghelli S, Scarpa A, Bassi C, Pederzoli P. Prognostic relevance of lymph node ratio and number of resected nodes after curative resection of ampulla of Vater carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:3178-3186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Fleming ID, Cooper JS, Henson DE, Hutter RVP, Kennedy BJ, Murphy GP, O’Sullivan B, Sobin LH, Yarbro JW. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven 1997; . |

| 50. | Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind Ch. International Union Against Cancer TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 7th ed. Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell 2009; . |

| 51. | Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press 2010; . |

| 52. | Ryan R, Gibbons D, Hyland JM, Treanor D, White A, MulcahyHE , O’Donoghue DP, Moriarty M, Fennelly D, Sheahan K. Pathological response following long-course neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. Histopathology. 2005;47:141-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 395] [Cited by in RCA: 496] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 53. | Gómez Mateo MC, Sabater Ortí L, Ferrández Izquierdo A. Protocolo de tallado, estudio e informe anatomopatológico de las piezas de duodenopancreatectomía cefálica por carcinoma de páncreas. Rev Esp Patol. 2010;43:207–214. [DOI] [Full Text] |