Published online Mar 15, 2024. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v16.i3.933

Peer-review started: August 18, 2023

First decision: October 23, 2023

Revised: November 5, 2023

Accepted: December 29, 2023

Article in press: December 29, 2023

Published online: March 15, 2024

Transanal endoscopic intersphincteric resection (ISR) surgery currently lacks sufficient clinical research and reporting.

To investigate the clinical effectiveness of transanal endoscopic ISR, in order to promote the clinical application and development of this technique.

This study utilized a retrospective case series design. Clinical and pathological data of patients with lower rectal cancer who underwent transanal endoscopic ISR at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University between May 2018 and May 2023 were included. All patients underwent transanal endoscopic ISR as the surgical approach. We conducted this study to determine the perioperative recovery status, postoperative complications, and pathological specimen characteristics of this group of patients.

This study included 45 eligible patients, with no perioperative mortalities. The overall incidence of early complications was 22.22%, with a rate of 4.44% for Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ III events. Two patients (4.4%) developed anastomotic leakage after surgery, including one case of grade A and one case of grade B. Postoperative pathological examination confirmed negative circumferential resection margins and distal resection margins in all patients. The mean distance between the tumor lower margin and distal resection margin was found to be 2.30 ± 0.62 cm. The transanal endoscopic ISR procedure consistently yielded high quality pathological specimens.

Transanal endoscopic ISR is safe, feasible, and provides a clear anatomical view. It is associated with a low incidence of postoperative complications and favorable pathological outcomes, making it worth further research and application.

Core Tip: In recent years, our center has conducted extensive research and accumulated experience in transanal endoscopic intersphincteric resection (ISR) procedures. In this study, we present the surgical outcomes, perioperative complications, and pathological findings based on the transanal endoscopic ISR surgeries performed in our center to contribute to the clinical application and development of this technique.

- Citation: Xu ZW, Zhu JT, Bai HY, Yu XJ, Hong QQ, You J. Clinical efficacy and pathological outcomes of transanal endoscopic intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2024; 16(3): 933-944

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v16/i3/933.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v16.i3.933

Intersphincteric resection (ISR) has been widely used in clinical practice as an advanced technique for ultralow rectal cancer with the aim of sphincter preservation. ISR involves the partial or complete removal of the internal sphincter while preserving the external sphincter, enabling patients to retain voluntary bowel function and significantly improving their postoperative quality of life compared with abdominoperineal resection (APR). Additionally, ISR ensures oncological safety[1,2]. Studies have shown that most patients achieve satisfactory anal continence after surgery. In 1994, Schiessel et al[3] proposed the ISR technique for ultralow rectal cancer, pushing the boundaries of sphincter preservation surgery and gradually gaining widespread recognition. In 2003, Rullier et al[4] first reported laparoscopic ISR. In 2017, Kiyasu et al[5] reported a case of transanal endoscopic ISR for treating rectal cancer in a patient with coexisting prostatic hyperplasia, demonstrating the safety and feasibility of this procedure. Currently, the transabdominal approach remains the most commonly used surgical method in clinical practice, with fewer reports on transanal endoscopic ISR. However, transanal endoscopic ISR offers unique anatomical advantages, particularly in terms of distal tumor margin and neural function preservation.

In recent years, our center has conducted extensive research and accumulated experience in transanal endoscopic ISR procedures. In this study, we present the surgical outcomes, perioperative complications, and pathological findings of transanal endoscopic ISR surgeries performed at our center with the aim of contributing to the clinical application and development of this technique.

This study used a retrospective case series design. Clinical and pathological data of patients with low rectal cancer who underwent transanal endoscopic ISR at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University (Xiamen, China) between May 2018 and May 2023 were collected. All patients underwent transanal endoscopic ISR as the surgical approach.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) Patients with biopsy-proven rectal adenocarcinoma who underwent transanal endoscopic ISR; (2) tumor extent of 2-5 cm from the anal verge based on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and intraoperative measurement; (3) tumors not involving the external anal sphincter as confirmed on MRI; and (4) patients with no distant metastases detected on preoperative imaging. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Missing surgical or pathological data; (2) preoperative imaging revealing distant metastases; (3) bleeding, bowel obstruction, or perforations requiring emergency surgery; and (4) preoperative anal sphincter dysfunction. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University.

The primary endpoints were the occurrence of postoperative complications and the histopathological specimen characteristics. The secondary endpoint was the perioperative recovery status. Complications were classified according to the Clavien-Dindo (CD) classification system[6]. The diagnosis and severity grading of anastomotic leakage will follow the 2010 criteria established by the International Study Group of Rectal Cancer[7].

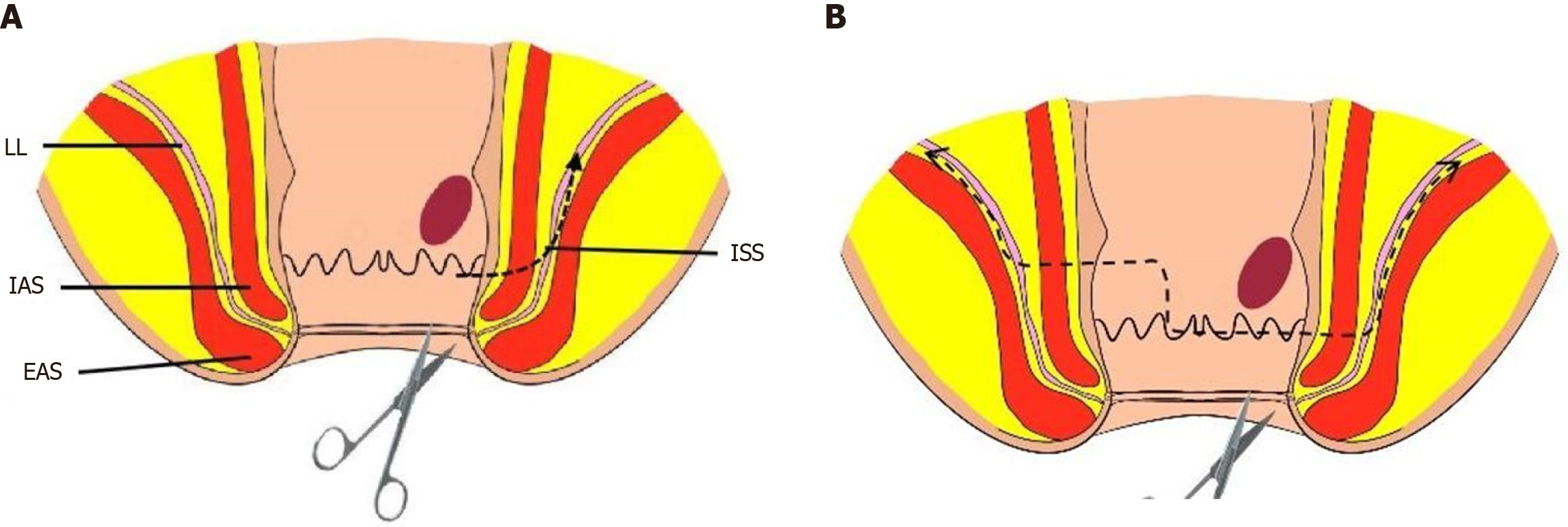

All surgeries were performed by two surgical groups simultaneously: one starting from the abdominal end and the other starting from the anal end. The primary surgeons in all cases had extensive experience in rectal cancer curative surgeries, performing over 200 annually. Surgeries were classified as partial, subtotal, or total ISR based on the distance between the tumor margin and the anal verge[3,8]. For cases where the distance between the tumor lower edge and the dentate line was ≥ 2 cm, partial ISR was performed, while for cases with a distance of 1-2 cm, subtotal ISR was performed. Total ISR was performed when the tumor was located within 1cm of the dentate line. Figure 1 show the surgical resection ranges.

The abdominal portion was performed under laparoscopic guidance, which involved preservation of the left colic artery and D3 lymph node dissection. Routine clearance of 253 lymph node groups was performed. The dissection was extended anteriorly to the seminal vesicles and posteriorly to the sacral fascia.

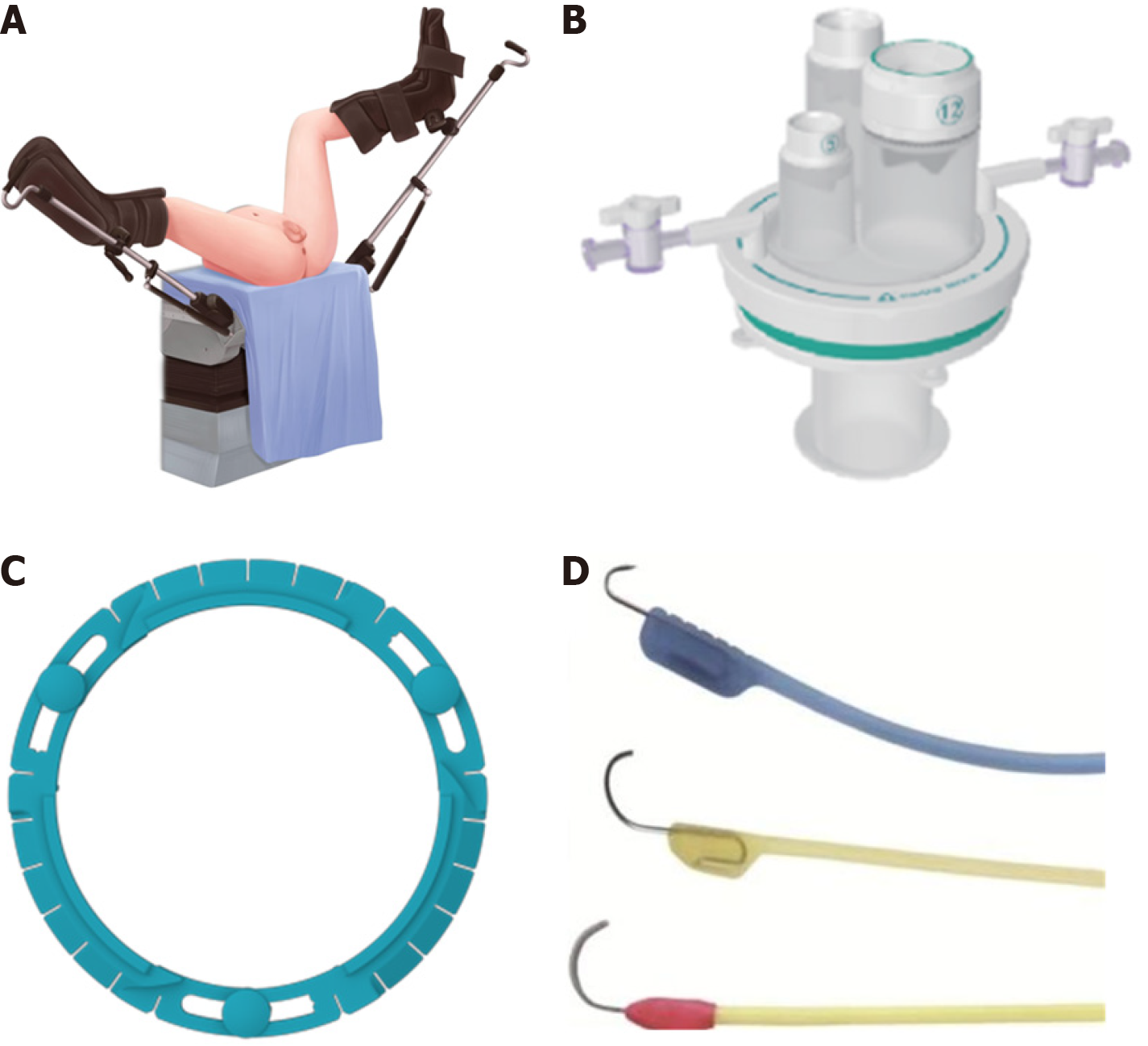

In the transanal portion, the single-port laparoscopic platform used in this study was the STAR-PORT soft single-port laparoscopic platform produced by Xiamen SAIKEDA Medical Equipment Co. (Xiamen, China). The insufflator used in this study was the AirSealTM constant pressure insufflator (ConMed, Utica, NY, United States), which typically provides a carbon dioxide insufflation pressure of 8-10 mmHg through the anal cavity. The primary energy devices used in this study were electrocautery hooks. Low-energy electrocautery hooks are commonly used for incising the intestinal wall and muscle tissues to identify the intersphincteric space (ISS). In cases where the anatomical plane was unclear, an ultrasonic scalpel was promptly employed to separate and locate the correct surgical plane. The appropriate choice of energy devices contributed to achieving a more precise dissection. The patient position and surgical instruments are shown in Figure 2, respectively.

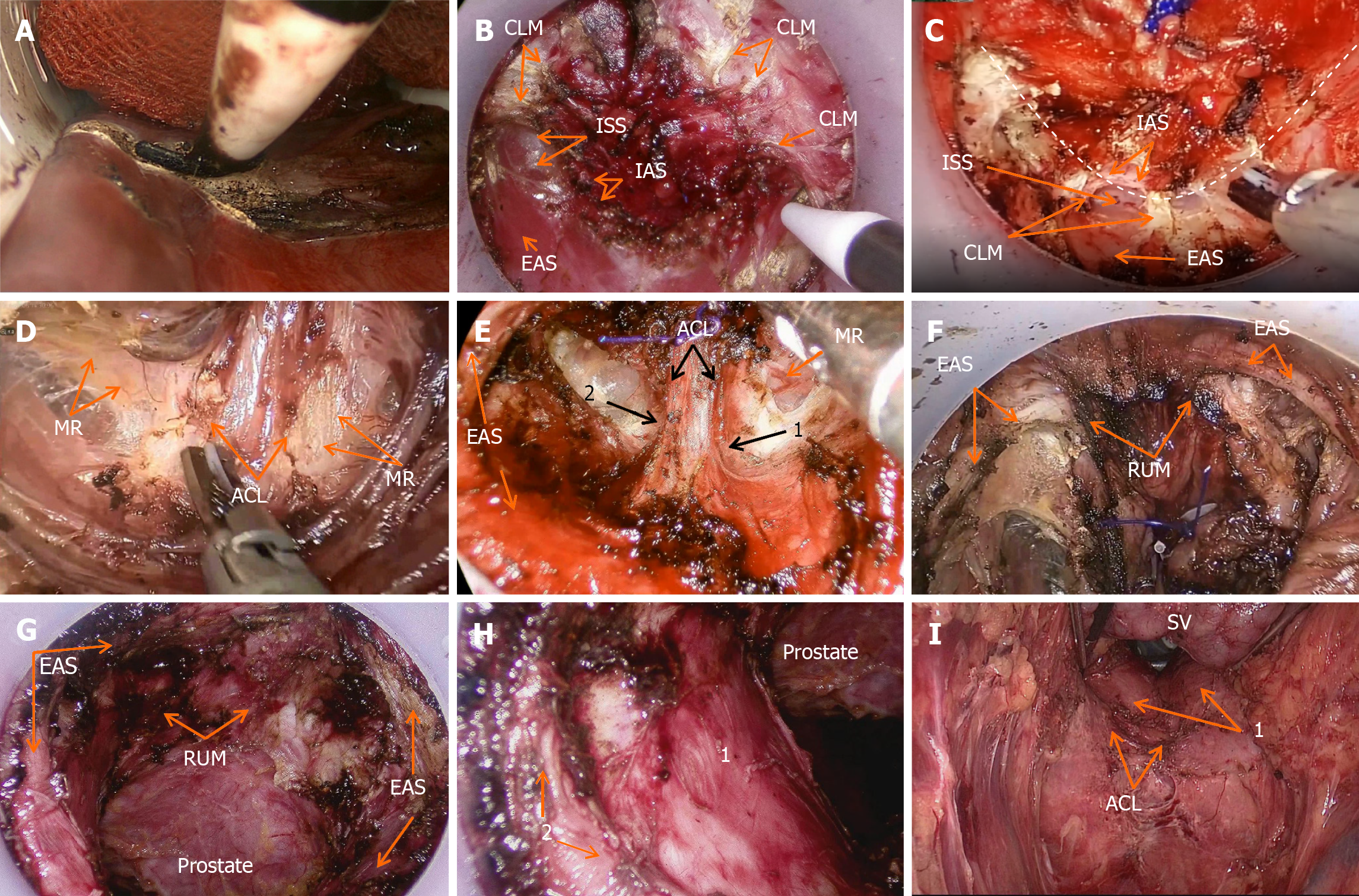

The intraoperative illustrations are shown in Figure 3. A lone star retractor was used to open the anus, and the distal rectum was sterilized. For patients undergoing modified ISR, a circular incision was made in the rectal wall or anal mucosa, with the incision line located 2 cm from the tumor on the tumor side. The incision line was arc-shaped towards the opposite side of the tumor with a lateral margin of approximately 1 cm, while preserving the normal inner sphincter and dentate line on the opposite side of the tumor. Under direct vision, the anal canal, inner sphincter, and combined longitudinal muscle were incised to expose ISS. To ensure safety of the circumferential resection margin (CRM), the surgical principle was to free the outer side of ISS, while removing the inner sphincter and combined longitudinal muscle. The bowel lumen was closed 1 cm from the distal end of the tumor using purse-string sutures to avoid the risk of tumor cell shedding during the operation and ensure an aseptic and tumor-free surgery.

After achieving sufficient exposure, the STAR-PORT was inserted into the ISS, and a carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum was established. ISS was dissected in the sequence posterior, lateral, and anterior. First, the posterior ISS was opened and part of the hiatal ligament and the ventral layer of the anococcygeal ligament were exposed. The remaining posterior hiatal ligament was separated along the 3-9 o’clock positions, and the hiatal ligament was cut to access the superior space of the levator ani. After clear exposure of the anococcygeal ligament, the ventral side of the anal coccygeal ligament was cut close to the anterior rectal wall, completing the dissection of the posterior half of the ISS. While dissecting the anterior ISS, the rectourethral muscle was cut close to the anterior rectal wall to reduce damage to the cavernous nerves in the rectourethral muscle and to preserve urinary and reproductive functions. Simultaneously, care was taken to protect the neurovascular bundles (NVBs) at the 2 o’clock and 10 o’clock positions and the pelvic plexus nerves in the rectal lateral space. After cutting the rectourethral muscle, dissection was conducted close to the posterior aspect of the prolapsed organ, and the surgical view was gradually lowered until it met the abdominal group, to avoid damaging organs such as the prostate. For female patients, the surgeon used their fingers to enter the vagina and guide the separation between the rectum and the posterior vaginal wall, reducing the risk of damaging the posterior vaginal wall.

Digestive tract reconstruction was performed using hand-sewn or stapler anastomoses. For patients undergoing hand-sewn anastomosis, the colonic wall was fully sutured to the corresponding site of the rectum at the 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-o’clock positions using four full-thickness sutures. Subsequently, the pre-placed four sutures were threaded from the outside to the inside and fully sutured to the corresponding site of the colon tube, followed by reinforcement to complete the digestive tract reconstruction. All patient underwent a loop ileostomy. Placement of a drainage tube in the pelvic cavity is a routinely performed. All surgical procedures adhered to the basic principles outlined in relevant clinical guidelines[9].

Postoperatively, all patients underwent regular follow-up, which included telephone consultations, outpatient visits, and inpatient examinations. Patients were followed up regularly every 3 mo during the 1st 2 years and every 6 mo thereafter. The follow-up examinations included laboratory blood tests, computed tomography, and physical examinations. Endoscopy is recommended annually after surgery.

Normally distributed continuous data are presented as the mean ± SD, while skewed distributed continuous data are presented as median (range). Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS (version 26.0; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, United States) software.

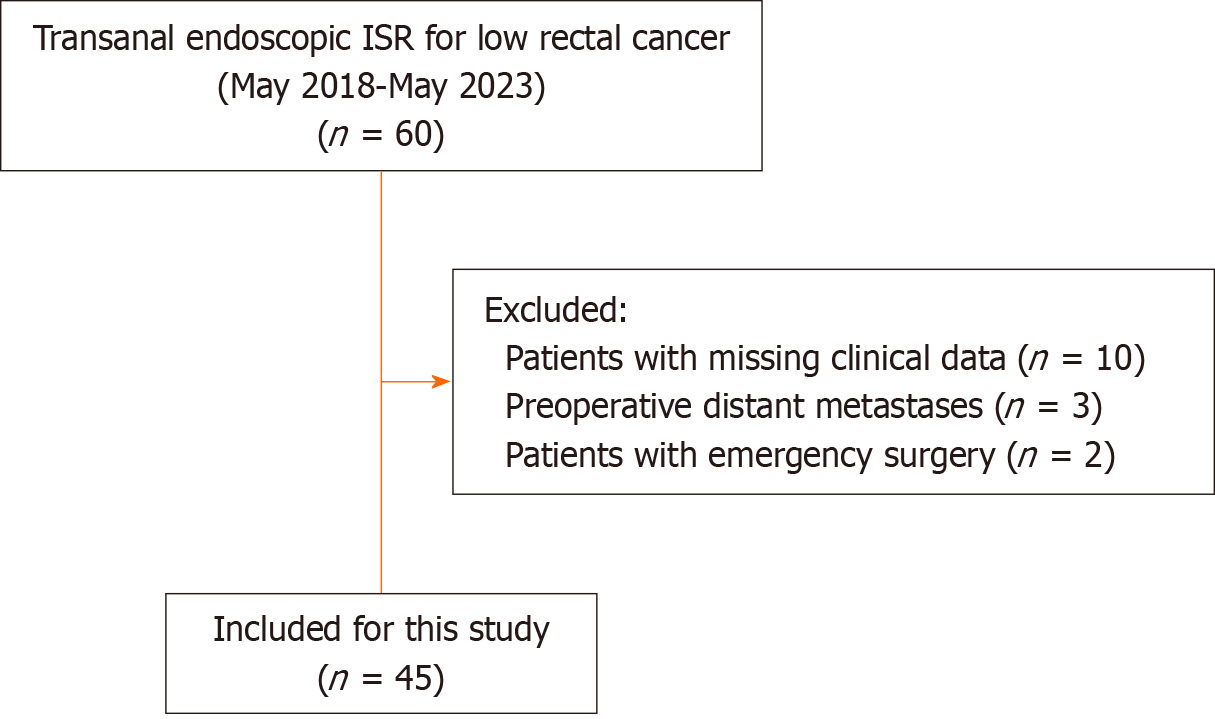

Table 1 shows the demographics and clinical characteristics of the patients. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 45 patients who underwent transanal endoscopic ISR between May 2018 and May 2023 were included in this study (Figure 4). The median distance between the tumors and the anal verges was 3.87 cm (range, 2.30-5.00 cm). Twelve (26.67%) patients had received neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. All patients underwent successful transanal endoscopic ISR surgeries according to the preoperative plan, and there were no perioperative deaths.

| Characteristic | Data |

| Sex | |

| Female | 16 (35.56) |

| Male | 29 (64.44) |

| Age in yr | 57.91 ± 12.571 |

| BMI in kg/m2 | 23.39 ± 3.41 |

| Weight in kg | 64.13 ± 11.40 |

| Hight in cm | 163.93 ± 6.93 |

| Hypertension | 9 (20.00) |

| Diabetic | 6 (13.33) |

| ASA grading | |

| I | 4 (8.89) |

| II | 33 (73.33) |

| III | 8 (17.78) |

| Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy | |

| No | 33 (73.33) |

| Yes | 12 (26.67) |

| Height from anal verge in cm | 3.87 (2.50-5.00) |

It took a median of 221.22 min (range, 120-345 min) to complete the whole procedure. The median intraoperative blood loss was 49.11 mL (range, 20-300 mL), median postoperative hospital stay was 10.29 d (range, 5-24 d), median time to resumption of oral intake was 5.47 d (range, 2-18 d) , median duration of gastric tube placement was 1.18 d (range, 0-3 d), and median duration of abdominal drainage tube placement was 8.76 d (range, 4-21 d) (Table 2).

| Characteristic | Data |

| Operative time in min | 221.22 (120-345) |

| Intraoperative blood loss in mL | 49.11 (20-300) |

| Anastomotic technique | |

| Stapled | 19 (42.22) |

| Manual | 26 (57.78) |

| Ileostomy or colostomy | |

| Yes | 45 (100) |

| No | 0 |

| Postoperative hospital stay in d | 10.29 (5-24) |

| Time to first soft diet in d | 5.47 (2-18) |

| Removal of abdominal drainage in d | 8.76 (4-21) |

| Removal of gastric tube in d | 1.18 (0-3) |

| Overall postoperative complications | 10 (22.22) |

| Anastomotic leakage | |

| Grade A | 1 (2.22) |

| Grade B | 1 (2.22) |

| Grade C | 0 |

| Intestinal obstruction | 3 (6.67) |

| Urinary retention | 1 (2.22) |

| Pelvic abscess | 1 (2.22) |

| Pulmonary infection | 6 (13.33) |

| Pleural effusion | 1 (2.22) |

| Clavien-Dindo classification | |

| Dindo I–II | 8 (17.78) |

| Dindo III–IV | 2 (4.44) |

| Dindo V | 0 |

| Readmission within 30 d | 0 |

| Death within 30 d | 0 |

Among our patients, 10 (22.2%) experienced postoperative complications, including 8 (17.78%) with CD grades I-II and 2 (4.44%) with CD grades III-IV events. There were no cases of CD grade V events. Two patients (4.44%) developed anastomotic leakage postoperatively and were successfully treated with abdominal drainage, irrigation, or antibiotic therapy. Three patients (6.67%) developed postoperative intestinal obstruction, one (2.22%) experienced urinary retention, one (2.22%) developed a pelvic abscess, six (13.33%) had lung infection, and one (2.22%) had pleural effusion. All complications were successfully managed with appropriate treatment. No readmissions or perioperative deaths occurred within 30 d of the procedure.

As shown in Table 3, among the 45 included patients, postoperative pathological examination revealed negative CRM and distal resection margin (DRM) in all patients. The mean distance between the lower tumor margin and DRM was found to be 2.30 ± 0.62 cm. The mean diameter of the tumors was 2.86 cm (range, 0.80-4.60 cm), with a median of 19.56 (range, 8-40) lymph nodes retrieved and a median of 0.91 (range, 0-7.0) positive lymph nodes. According to the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system, the postoperative pathological tumor-node-metastasis stages were as follows: stage I, 24 patients (53.33%); stage II, 7 (15.56%); and stage III, 14 (31.11%).

| Characteristic | Data |

| Pathological T stage | |

| T1 | 3 (6.67) |

| T2 | 32 (71.11) |

| T3 | 10 (22.22) |

| Pathological N stage | |

| N0 | 31 (68.89) |

| N1 | 10 (22.22) |

| N2 | 4 (8.89) |

| Pathological TNM stage | |

| I | 24 (53.33) |

| II | 7 (15.56) |

| III | 14 (31.11) |

| Tumor size in cm | 2.86 (0.80-4.60) |

| Number of lymph nodes harvested | 19.56 (8-40) |

| Number of positive lymph nodes | 0.91 (0-7.0) |

| Length between tumor and DRM in cm | 2.30 ± 0.62 |

| CRM status | |

| Positive | 0 |

| Negative | 45 (100) |

| DRM status | |

| Positive | 0 |

| Negative | 45 (100) |

Transanal endoscopic ISR as an emerging technique for the treatment of ultralow rectal cancer has gradually been adopted in clinical practice in recent years. With the magnified view provided by the endoscope, transanal endoscopic ISR allows for tumor excision through the anal canal approach, offering significant advantages over transabdominal ISR in terms of determining the distal margin and preserving NVB surrounding the rectum.

ISR has shown promising results as an established technique for sphincter preservation in the treatment of ultralow rectal cancer. Research indicates that achieving a 1 cm DRM and a 1 mm CRM in ISR can lead to a 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) rate of 80.2% and local recurrence (LR) rate of 5.8%[10]. For experienced surgical teams, oncological outcomes were completely safe and assured. In a comparative study by Koyama et al[11] on APR and transabdominal ISR, the LR rate in the APR group of 33 patients was 12.1%, whereas the ISR group of 77 patients had a lower LR rate of 7.8%. Moreover, the 5-year overall survival (OS) rate in the APR group was 51.2%, which was lower than that in the ISR group (76.4%). In another large-scale study on the survival prognosis in patients with low rectal cancer, the 3-year cumulative LR rates were 3.9% and 7.3% in the APR and ISR groups, respectively, whereas the 5-year OS rates were 67.9% and 69.9% in the APR and ISR groups, respectively[2]. Similarly, in a retrospective comparative study conducted by Kim et al[12], which included 624 patients with rectal cancer undergoing low anterior resection (LAR) and ISR, the results showed no statistically significant differences in the 5-year OS, DFS, or LR between the LAR and ISR groups. In a comparative study by Liu et al[13] on transanal total mesorectal excision (TaTME) combined with ISR vs APR, the 3-year DFS rate was 86.3% in the TaTME combined with ISR group and 75.1% in the APR group. The 3-year OS was 96.7% in the TaTME combined with ISR group and 94.2% in the APR group, with no statistically significant differences between the two surgical approaches in terms of 3-year DFS and OS for the patients. The aforementioned studies collectively suggest that both traditional transabdominal ISR and transanal endoscopic ISR achieve oncological outcomes comparable to those of APR and even show potential for better survival prognosis in some studies. Both approaches are feasible from an oncological safety perspective.

The average postoperative hospital stay for patients in our study was 10.29 (5-24) d, and most patients had their gastric tubes removed on the 2nd postoperative day. Our study found an overall postoperative complication rate of 22.22%, and the incidence of major complications (CD grade ≥ 3) was low (4.44%). Pulmonary infections were the most common complications, possibly related to the older age of patients. Previous studies have consistently shown that the incidence of postoperative complications after ISR to be 17.2%-25.8%[14,15], which is consistent with the findings of the present study. Three cases of intestinal obstruction occurred during the perioperative period, and early mobilization of patients and avoidance of prolonged bed rest further reduced the occurrence rate. Considering multiple research results, the incidence of anastomotic leakage after surgery for low rectal cancer is mostly between 5.3% and 13.9%[16-18]. In our study, only 2 patients experienced anastomotic leakage, with an incidence rate of 4.44%, which was significantly lower than the aforementioned results. We believe that this is related to the excellent preservation of vascular and neural bundles achieved through the transanal endoscopic approach, which reduces the risk of ischemia in the vicinity of the anastomosis.

One patient experienced urinary retention, and after reviewing the surgical video, we found that this might have been related to intraoperative damage to the genitourinary nerves. The patient was treated with catheterization and appropriate bladder function exercises, which resulted in a good recovery. However, it is worth noting that in our study, the incidence rate of perioperative urinary retention was only 2.22%. Based on a comparison with several previous studies on transabdominal approach surgeries, we found that the incidence of urinary dysfunction during the perioperative period was mostly between 3.1% and 41.0%[19-21], which is significantly higher than that observed in our study. This notable difference can be attributed to the favorable exposure and preservation of the genitourinary nerves achieved through the transanal endoscopic approach during dissection, as opposed to the traditional transabdominal approach. Therefore, we can observe the significant advantages of transanal endoscopic ISR in preserving genitourinary function.

Radical tumor resection is a crucial factor in determining surgical outcomes; otherwise, it may significantly affect patients' postoperative survival and risk of recurrence. DRM, CRM, and the number of lymph nodes removed are all essential indicators of surgical radicality. In this study, all patients had negative DRM and CRM, with the tumor DRM distance being 2.30 cm ± 0.62 cm, indicating high-quality surgical specimens. A significant advantage of the transanal endoscopic approach for ISR is that it can precisely ensure a safe distance from the DRM while achieving optimal sphincter preservation. During surgery, purse-string sutures are usually placed 1 cm away from the distal end of the tumor under direct visualization. This step not only seals the distal end of the tumor to avoid a potential risk of tumor cell shedding, but also ensures that all patients have a DRM of > 1 cm. After closing the distal end of the rectum, a circular incision was made 1 cm away from the purse-string suture to determine the resection line. Therefore, in most cases, a DRM of ≥ 2 cm can be ensured. For patients who cannot achieve a 2-cm DRM, we usually perform an intraoperative rapid frozen tissue histopathological examination to ensure an unequivocally negative DRM.

In recent years, studies have found that rectal cancer rarely infiltrates the distal margins. Research has confirmed that there is no statistically significant difference in LR and OS between a 2 cm DRM and a 5 cm DRM[22,23]. Therefore, a 2 cm DRM is also widely accepted as the margin distance by many surgeons. Further research has revealed that in the majority of lower rectal cancers, tumor cells infiltrate the distal margin to a distance less than 1 cm. In a meta-analysis involving 5574 patients, it was found that there was no statistically significant difference in LR and OS between a DRM of > 1 cm and that of < 1 cm[24]. Another study on prognostic factors after ISR found that a DRM of < 1 cm was not an independent risk factor for postoperative LR and OS[25]. For extremely precious distal rectal segments close to the dentate line, we believe that a DRM of > 1 cm is sufficient to ensure oncological safety.

In a meta-analysis by Martin et al[15] that included 14 studies comprising a total of 1289 cases of ISR for rectal cancer, the overall negative rate of CRM was 96.0% and the R0 resection rate was 97%. This study also demonstrated that the CRM status independently influences the survival prognosis of patients with ISR. By contrast, our study demonstrated that transanal endoscopic ISR yields high-quality pathological specimens. We believe that this is mainly due to the unique advantage of transanal endoscopy in distinguishing rectal and anal structures during intraoperatively. In addition, the total number of lymph nodes removed during surgery in our study was 19.56 (range, 8-40). As the abdominal portion of the procedure is consistent with the traditional laparoscopic approach for ISR, the lymph node retrieval is comparable to the traditional transabdominal approach[26,27].

The physiological curvature in the anatomy of the rectum makes it challenging to achieve precise localization of DRM during ISR while using a transabdominal approach[28,29]. Moreover, for patients with pelvic narrowing, the separation of ISS can be even more challenging. In the traditional laparoscopic ISR procedure, the transanal portion requires direct visualization of the separation of the distal rectum and ISS. However, the clarity of the visual field is not as good as that with transanal endoscopy. At our center, we use the transanal endoscopic ISR technique for the treatment of ultralow rectal cancer. With the high-definition magnification provided by the transanal endoscope and the expansion of the port, the visual field can be better exposed, making the separation of the ISS simpler, more accurate, and facilitating the precise localization of the DRM. In the transanal endoscopic view, both radial fibers of the combined longitudinal muscle and the internal anal sphincter are clearly visible. The use of an electric cautery allows for the distinct identification of the contracting red external anal sphincter and the non-contracting white internal anal sphincter.

Our experience is generally to start by freeing the posterior ISS, then proceed to freeing the space on both sides, and finally moving to the anterior ISS. When freeing the posterior and lateral ISS, as we enter the space above the levator ani muscle, we closely adhere to the rectal posterior rectal wall and cut the abdominal layer of the anococcygeal ligament. The hiatal ligament forms a U-shaped closure of the puborectal hiatus, and has a firm texture, whereas the tissues at the 5 o’clock and 7 o’clock positions of the lithotomy position are relatively weak. We believe that the optimal approach is to first open the posterior ISS and dissect it towards the head to expose a portion of the hiatal ligament and the anterior aspect of the anorectal ligament. Subsequently, in a U-shaped manner, we continued to separate the remaining posterior hiatal ligament, with the separation extending approximately along the 3 o’clock to 9 o’clock positions of the lithotomy position, allowing access to the puborectal hiatus in this area by cutting the hiatal ligament. After cutting the posterior hiatal ligament, we closely dissected the rectal posterior wall to cut the abdominal layer of the anococcygeal ligament.

When separating the anterior ISS, our experience involves using a low-energy setting on electric cautery, which effectively reduces bleeding and nerve damage. There is generally a weak area in the levator ani muscle, regardless of whether in male or female patients. In males patients, this weak area is usually located between the 11 o'clock and 1 o'clock positions, while in female patients, it is located between the 10 o'clock and 2 o'clock positions[30]. During the dissection of the anterior ISS, this weak point can be used as a starting point to locate the rectourethral muscle, which is situated behind the external sphincter ring. After dividing the fibers of the rectourethral muscle, the Denonvilliers' fascia can be reached, and the urethra in men or the posterior wall of the vagina in women can be exposed, entering the prerectal space. During the dissection of the anterior ISS, it is necessary to approach the rectal anterior wall to divide the rectourethral muscle and minimize damage to the cavernous nerves, thereby preserving the patient's urinary and reproductive functions. Careful identification and protection of NVB at the 2 o'clock and 10 o'clock positions and the pelvic plexus nerves within the lateral rectal space are essential. These nerves play a critical role in preserving postoperative sexual function for the patients[31-33]. By paying close attention to identification and employing gentle techniques, it is possible to minimize damage to these crucial nerve structures, thereby maximizing the preservation of postoperative sexual function. Preserving sexual and urinary functions in patients with lower rectal cancer is a challenging aspect of the surgery[34]. However, utilizing the visual and angular advantages of transanal endoscopy allows for excellent protection of the aforementioned sexual and urinary-related organs and nerves. This is of significant importance in safeguarding pelvic autonomic nerve function.

Throughout the surgical procedure, the surgeon should strictly adhere to the principles of total mesorectal excision and consistently emphasize the awareness of meticulous vascular and nerve dissection and protection. Only in this manner can the advantages of the transanal endoscopic approach for ISR be fully maximized.

In summary, this study reports on the transanal endoscopic ISR surgeries performed at our center in recent years. This study found that transanal endoscopic ISR offers excellent surgical visualization and facilitates the protection of the perirectal vasculature and nerves. This procedure is associated with minimal postoperative complications, yields high-quality pathological specimens, and has excellent oncological outcomes. This study has valuable implications for the widespread implementation of the transanal endoscopic ISR. However, further investigations with larger sample sizes are warranted.

Transanal endoscopic intersphincteric resection (ISR).

Transanal endoscopic ISR surgery currently lacks sufficient clinical research and reporting. In this study, we present the surgical outcomes, perioperative complications, and pathological findings based on the transanal endoscopic ISR surgeries performed in our center, aiming to contribute to the clinical application and development of this technique.

This study utilized a retrospective case series study design. Clinical and pathological data of patients with low rectal cancer who underwent transanal endoscopic ISR at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University from May 2018 to May 2023 were collected. All patients underwent transanal endoscopic ISR as the surgical approach.

This study utilized a retrospective case series study design. Clinical and pathological data of patients with low rectal cancer who underwent transanal endoscopic ISR at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University from May 2018 to May 2023 were collected. All patients underwent transanal endoscopic ISR as the surgical approach. We conducted a study to report on the perioperative recovery status, postoperative complications, and pathological specimen characteristics of this group of patients.

This study included a total of 45 eligible cases, with no perioperative deaths. The overall incidence of early complications was 22.22%, with a rate of 4.44% for Clavien-Dindo ≥ III. Two patients (4.4%) developed anastomotic leakage after surgery, including one case of grade A and one case of grade B. Postoperative pathological examination confirmed negative circumferential resection margin and distal resection margin (DRM) in all patients. The distance between the tumor lower margin and DRM was found to be 2.30 ± 0.62 cm. Transanal endoscopic ISR surgery consistently yields excellent quality pathological specimens.

In summary, this study provides a report on the transanal endoscopic ISR surgeries performed at our center in recent years. The study found that transanal endoscopic ISR offers excellent surgical visualization and facilitates the protection of the perirectal vasculature and nerves. The procedure has minimal postoperative complications, yields high-quality pathological specimens, and demonstrates excellent oncological outcomes. This research holds valuable implications for the widespread implementation of the transanal endoscopic ISR technique. However, further investigations with larger sample sizes are still warranted.

Furthermore, there is limited literature available on the long-term efficacy of transanal endoscopic ISR. Subsequent studies conducted by our research team will focus on long-term survival outcomes, utilizing our center’s data, to further validate and explore these aspects.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hidaka E, Japan; Kumar A, India; Wani I, India S-Editor: Qu XL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Akagi Y, Shirouzu K, Ogata Y, Kinugasa T. Oncologic outcomes of intersphincteric resection without preoperative chemoradiotherapy for very low rectal cancer. Surg Oncol. 2013;22:144-149. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tsukamoto S, Miyake M, Shida D, Ochiai H, Yamada K, Kanemitsu Y. Intersphincteric Resection Has Similar Long-term Oncologic Outcomes Compared With Abdominoperineal Resection for Low Rectal Cancer Without Preoperative Therapy: Results of Propensity Score Analyses. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61:1035-1042. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Schiessel R, Karner-Hanusch J, Herbst F, Teleky B, Wunderlich M. Intersphincteric resection for low rectal tumours. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1376-1378. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 334] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rullier E, Sa Cunha A, Couderc P, Rullier A, Gontier R, Saric J. Laparoscopic intersphincteric resection with coloplasty and coloanal anastomosis for mid and low rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2003;90:445-451. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 150] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kiyasu Y, Kawada K, Hashimoto K, Takahashi R, Hida K, Sakai Y. Transanal approach for intersphincteric resection of rectal cancer in a patient with a huge prostatic hypertrophy. Int Cancer Conf J. 2017;6:1-3. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18532] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21934] [Article Influence: 1096.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS), American Society of Neuroradiology (ASNR), Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology Society of Europe (CIRSE), Canadian Interventional Radiology Association (CIRA), Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS), European Society of Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy (ESMINT), European Society of Neuroradiology (ESNR), European Stroke Organization (ESO), Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI), Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR), Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery (SNIS), and World Stroke Organization (WSO), Sacks D, Baxter B, Campbell BCV, Carpenter JS, Cognard C, Dippel D, Eesa M, Fischer U, Hausegger K, Hirsch JA, Shazam Hussain M, Jansen O, Jayaraman MV, Khalessi AA, Kluck BW, Lavine S, Meyers PM, Ramee S, Rüfenacht DA, Schirmer CM, Vorwerk D. Multisociety Consensus Quality Improvement Revised Consensus Statement for Endovascular Therapy of Acute Ischemic Stroke. Int J Stroke. 2018;13:612-632. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 279] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schiessel R, Novi G, Holzer B, Rosen HR, Renner K, Hölbling N, Feil W, Urban M. Technique and long-term results of intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1858-65; discussion 1865. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 157] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | TaTME Guidance Group representing the ESCP (European Society of Coloproctology), in collaboration with the ASCRS (American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons), ACPGBI (Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland), ECCO (European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation), EAES (European Association of Endoscopic Surgeons), ESSO (European Society of Surgical Oncology), CSCRS (Canadian Society of Colorectal Surgery), CNSCRS (Chinese Society of Colorectal Surgery), CSLES (Chinese Society of Laparo-Endoscopic Surgery), CSSANZ (Colorectal Surgical Society of Australia and New Zealand), JSES (Japanese Society of Endoscopic Surgery), SACP (Argentinian Society of Coloproctology), SAGES (Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons), SBCP (Brazilian Society of Coloproctology), Swiss-MIS (Swiss Association for Minimally Invasive Surgery). International expert consensus guidance on indications, implementation and quality measures for transanal total mesorectal excision. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22:749-755. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Denost Q, Moreau JB, Vendrely V, Celerier B, Rullier A, Assenat V, Rullier E. Intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer: the risk is functional rather than oncological. A 25-year experience from Bordeaux. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22:1603-1613. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Koyama M, Murata A, Sakamoto Y, Morohashi H, Takahashi S, Yoshida E, Hakamada K. Long-term clinical and functional results of intersphincteric resection for lower rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21 Suppl 3:S422-S428. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kim JC, Yu CS, Lim SB, Kim CW, Park IJ, Yoon YS. Outcomes of ultra-low anterior resection combined with or without intersphincteric resection in lower rectal cancer patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:1311-1321. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liu ZH, Zeng ZW, Jie HQ, Huang L, Luo SL, Liang WF, Zhang XW, Kang L. Transanal total mesorectal excision combined with intersphincteric resection has similar long-term oncological outcomes to laparoscopic abdominoperineal resection in low rectal cancer: a propensity score-matched cohort study. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2022;10:goac026. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Min L, Fan Z, Zhi W, Pingang L, Lijuan X, Min D, Yan W, Xiaosong W, Bo T. Risk Factors for Anorectal Dysfunction After Interspincteric Resection in Patients With Low Rectal Cancer. Front Surg. 2021;8:727694. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Martin ST, Heneghan HM, Winter DC. Systematic review of outcomes after intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2012;99:603-612. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 160] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Park JS, Choi GS, Kim SH, Kim HR, Kim NK, Lee KY, Kang SB, Kim JY, Kim BC, Bae BN, Son GM, Lee SI, Kang H. Multicenter analysis of risk factors for anastomotic leakage after laparoscopic rectal cancer excision: the Korean laparoscopic colorectal surgery study group. Ann Surg. 2013;257:665-671. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 293] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Trencheva K, Morrissey KP, Wells M, Mancuso CA, Lee SW, Sonoda T, Michelassi F, Charlson ME, Milsom JW. Identifying important predictors for anastomotic leak after colon and rectal resection: prospective study on 616 patients. Ann Surg. 2013;257:108-113. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 213] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | van der Pas MH, Haglind E, Cuesta MA, Fürst A, Lacy AM, Hop WC, Bonjer HJ; COlorectal cancer Laparoscopic or Open Resection II (COLOR II) Study Group. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer (COLOR II): short-term outcomes of a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:210-218. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1030] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 883] [Article Influence: 80.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Xv Y, Fan J, Ding Y, Hu Y, Jiang Z, Tao Q. Latest Advances in Intersphincteric Resection for Low Rectal Cancer. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2020;2020:8928109. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Changchien CR, Yeh CY, Huang ST, Hsieh ML, Chen JS, Tang R. Postoperative urinary retention after primary colorectal cancer resection via laparotomy: a prospective study of 2,355 consecutive patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1688-1696. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Imaizumi K, Tsukada Y, Komai Y, Nomura S, Ikeda K, Nishizawa Y, Sasaki T, Taketomi A, Ito M. Prediction of urinary retention after surgery for rectal cancer using voiding efficiency in the 24 h following Foley catheter removal. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2019;34:1431-1443. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kwok SP, Lau WY, Leung KL, Liew CT, Li AK. Prospective analysis of the distal margin of clearance in anterior resection for rectal carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1996;83:969-972. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 61] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Andreola S, Leo E, Belli F, Lavarino C, Bufalino R, Tomasic G, Baldini MT, Valvo F, Navarria P, Lombardi F. Distal intramural spread in adenocarcinoma of the lower third of the rectum treated with total rectal resection and coloanal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:25-29. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 86] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bujko K, Rutkowski A, Chang GJ, Michalski W, Chmielik E, Kusnierz J. Is the 1-cm rule of distal bowel resection margin in rectal cancer based on clinical evidence? A systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:801-808. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 90] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Piozzi GN, Park H, Lee TH, Kim JS, Choi HB, Baek SJ, Kwak JM, Kim J, Kim SH. Risk factors for local recurrence and long term survival after minimally invasive intersphincteric resection for very low rectal cancer: Multivariate analysis in 161 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47:2069-2077. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ou W, Wu X, Zhuang J, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Liu X, Guan G. Clinical efficacy of different approaches for laparoscopic intersphincteric resection of low rectal cancer: a comparison study. World J Surg Oncol. 2022;20:43. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zhang B, Zhuo GZ, Zhao K, Zhao Y, Gao DW, Zhu J, Ding JH. Cumulative Incidence and Risk Factors of Permanent Stoma After Intersphincteric Resection for Ultralow Rectal Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65:66-75. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ito M. ISR for T1-2 Low Rectal Cancer: A Japanese Approach. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2020;33:361-365. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zang Y, Zhou M, Tan D, Li Z, Gu X, Yang Y, Wang Z, Chen Z, Zhou Y, Xiang J. An anatomical study on intersphincteric space related to intersphincteric resection for ultra-low rectal cancer. Updates Surg. 2022;74:439-449. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Arakawa T, Murakami G, Nakajima F, Matsubara A, Ohtsuka A, Goto T, Teramoto T. Morphologies of the interfaces between the levator ani muscle and pelvic viscera, with special reference to muscle insertion into the anorectum in elderly Japanese. Anat Sci Int. 2004;79:72-81. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Costello AJ, Brooks M, Cole OJ. Anatomical studies of the neurovascular bundle and cavernosal nerves. BJU Int. 2004;94:1071-1076. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 298] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 244] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Eichelberg C, Erbersdobler A, Michl U, Schlomm T, Salomon G, Graefen M, Huland H. Nerve distribution along the prostatic capsule. Eur Urol. 2007;51:105-10; discussion 110. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 101] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Liang JT, Lai HS, Lee PH. Laparoscopic pelvic autonomic nerve-preserving surgery for patients with lower rectal cancer after chemoradiation therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1285-1287. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 94] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Sylla P, Knol JJ, D'Andrea AP, Perez RO, Atallah SB, Penna M, Hompes R, Wolthuis A, Rouanet P, Fingerhut A; International taTME Urethral Injury Collaborative. Urethral Injury and Other Urologic Injuries During Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision: An International Collaborative Study. Ann Surg. 2021;274:e115-e125. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |