Published online Aug 15, 2018. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v10.i8.211

Peer-review started: April 16, 2018

First decision: May 9, 2018

Revised: May 14, 2018

Accepted: June 27, 2018

Article in press: June 28, 2018

Published online: August 15, 2018

To analyse the safety and efficacy of curative intent surgery in biliary and pancreatic cancer.

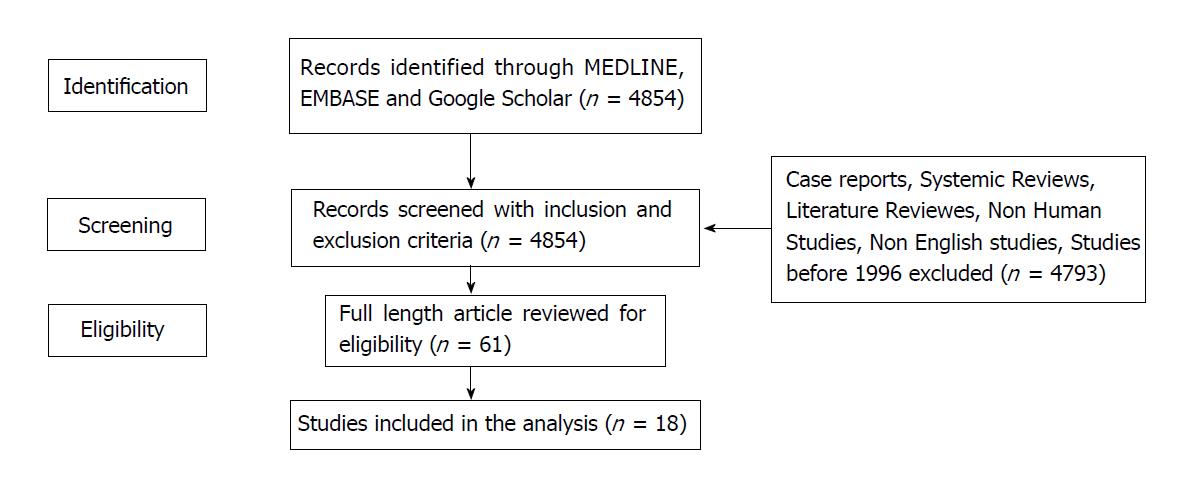

An extensive literature review was performed using MEDLINE, Google Scholar and EMBASE to identify articles regarding hepato-pancreatoduodenectomy or resection of liver metastasis in patients with pancreatic, biliary tract, periampullary and gallbladder cancers.

A total of 19 studies were identified and reviewed. Major hepatectomy was undertaken in 391 patients. The median overall survival for pancreatic cancer ranged from 5-36 mo and for biliary tract/gallbladder cancer, it was 8-38 mo. The 30 d mortality rate was only 1%-9%. Overall Survival was significantly better for patients, who had good response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, underwent metachronous liver resection and who had intestinal type tumours.

Resection of liver metastases in pancreatic and biliary cancers may provide survival benefit without compromising safety and quality of life in a very select group of patients. These data may be utilised to formulate selection criteria that may allow future investigation of resection in the era of more effective systemic therapy.

Core tip: Hepatic resection may be feasible for highly selected pancreatic and biliary tract cancer patients with a propensity towards improved outcomes and provide a chance for long term survival. The longer disease free interval between primary tumour and the liver metastases, response to the neoadjuvant treatment and other prognostic markers may also facilitate better selection of patients with more favourable tumour biology and prognosticate individual patient.

- Citation: Lee RC, Kanhere H, Trochsler M, Broadbridge V, Maddern G, Price TJ. Pancreatic, periampullary and biliary cancer with liver metastases: Should we consider resection in selected cases? World J Gastrointest Oncol 2018; 10(8): 211-220

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v10/i8/211.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v10.i8.211

Hepatic metastases are 18 to 40 times more common than primary liver cancers[1]. Better understanding of tumour biology, improved techniques for liver resection[2,3] and multidisciplinary treatments have led to new algorithms for managing metastatic disease in the liver. For selected patients, surgical resection of liver metastases in colorectal cancer has shown 5-year survival rates as high as 40% to 71%[4-8] and for neuroendocrine tumours, the 5-year survival ranges between 61% to 76% can be achieved[9-12]. Fewer studies have also shown benefit of liver resection in noncolorectal non-neuroendocrine liver metastases with 5-year survival of 36%[13-15]. Very similar long term outcome was recently reported after liver resection for non-colorectal non-neuroendocrine liver metastases in an Australian setting[16].

There is existing evidence in literature including a national registry based study in Sweden which documents feasibility and benefit of hepatectomy for hepatobiliary (pancreas, gall bladder and cholangiocarcinoma, ampullary) liver metastases[17-25]. Prior reviews of gastric and oesophageal cancer have been published and suggest that in highly selected patients, prolonged survival can be achieved[26]. However, resection of liver metastases from other primary tumours still remains controversial because of the heterogeneity of the data and fewer patients are referred for assessment of resectability.

Evolution of new neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimens has a significant potential to downstage cancers to potentially resectable state. This coupled with increased safety of liver resections has led to expansion of indications for patients being suitable for resection of metastatic disease, particularly in colorectal cancer[27-31]. Importantly significant advances have been made in systemic therapy in recent times for hepatobiliary cancers with regimens such as infusional FU, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan (FOLFIRINOX) in pancreatic cancer having response rates over 30%[32]. Furthermore, staging of disease has improved greatly and therefore identifying oligometastatic disease, in particular isolated liver metastasis is far more accurate. With these changes in mind we undertook a review and analysed data in the literature related to the role of curative surgery for hepatic metastasis in periampullary, biliary and pancreatic cancers.

A comprehensive literature search of MEDLINE, EMBASE along with Google Scholar was performed by using the following key words: Pancreatic cancer, biliary cancer, ampullary cancer, liver metastasis, metastasectomy, metastasis resection, pancreatoduodenectomy. The key words were identified either independently or in various combinations in order to retrieve the maximum number of relevant search results. Conference abstracts were also included due to limited studies available for analysis. Furthermore, the references of all selected articles were reviewed to identify any additional, potentially eligible studies. All the published studies conducted from 1996 to 2017 were included in analysis. Heterogeneity of studies was evaluated by analyzing comparability of the following items: Number of patients, grade or stage of disease, type of surgery performed, type of adjuvant treatment applied.

All prospective or retrospective studies reporting outcomes post liver metastasectomy for pancreatic and biliary tract cancer were included. The primary goal of this study was better evaluation of the safety and clinical efficacy of hepatectomy for synchronous and metachronous liver metastases of pancreatic and biliary cancer hepatic metastases. Outcome measures of interest included the post-operative mortality, median overall survival, 5-year survival rate and prognostic factors associated with survival.

Studies were restricted to those in English only and were excluded if outcome measures of interest especially survival data was not reported or could not be extracted. Studies limited to cell lines or animal models were also excluded from this review.

All studies meeting selection criteria were reviewed by the first and last author to determine eligibility. The data and studies available were too small and heterogeneous for a systematic review to be carried out (Figure 1).

A total of 11 studies were identified with 281 patients. Four studies evaluated benefit of both synchronous and metachronous liver resection while 7 studies included only synchronous liver resection. Morbidity rate varied from 20% to 68%[33-38]. For patients with synchronous liver metastases, most common type of pancreatic resection was pancreatoduodenectomy (n = 125) followed by distal pancreatectomy (n = 75) and total pancreatectomy (n = 27) and most common type of liver resection performed were atypical resection (n = 61), wedge resection (n = 32) and segmentectomy (n = 25) with hepatectomy (n = 5) being less common. Synchronous liver resection had higher morbidity than metachronous liver resection (33%-45% vs 0%-21%)[39,40]. Common complications were infection, bleeding and pancreatic fistula. The 30 d post-operative mortality was between 0% to 9.1%[36-39]. Sixty percent of patients had disease recurrence in liver after curative resection[34,35] (Tables 1 and 2). A few case series have showed favourable results with regards to overall survival (OS). They have reported one-year survival rates of 36%-41% after synchronous resection of solitary liver metastases in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer with proper patient selection[33,36,41].

| n | Age | No. of hepatic metastases | Median size of liver metastases | Chemotherapy | Mortality rate | |

| Hackert et al[39], 2017 | 85 | 60 | 96% had 3 lesions 3 had > 3 lesions | 31% had 1-2 cm 43% had < 1 cm | 74% received Adjuvant gemcitabine or 5 FU | 2.90% |

| Crippa et al[34], 2016 | 11 | 65 (35-80) | 10% had 1 28% had 1-5 61% had > 5 | NA | Neoadjuvant gemcitabine (14%), 30% gemcitabine + nab-paclitaxel while 66% had FOLFIRINOX, PEFG, PEXG or PDXG | 0 |

| Tachezy et al[38], 2016 | 69 | 65 (31-83) | 2 (1-11) | NA | Neoadjuvant gemcitabine in 4% or FOLFIRINOX in 14%. Adjuvant in 80%, 80% got gemcitabine and 7% FOLFIRINOX | 1% |

| Zanini et al[35], 2015 | 15 | 55 (52-64) | 2 (1-3) 60% had 1 lesion | 2.2 cm (1.8-2.5) | Adjuvant gemcitabine | 0 |

| Klein et al[33], 2012 | 22 | 57.5 (31-78) | NA | NA | Adjuvant gemcitabine | 0 |

| Dünschede et al[40], 2010 | 9 | 55 (39-72) | 3 (1-5) | 3.5 (1-9) | 0 | |

| Gleisner et al[37], 2007 | 17 | 64.7 ± 11.4 | 1 (1-1) | 0.6 (0.3-1.2) | 6 received 5FU or gemcitabine | 9.10% |

| Shrikhande et al[36], 1996 | 11 | 65 (60-74) | 2 (1-3) | NA | Adjuvant Gemcitabine or 5FU or radiation | 0 |

| N | Median OS(mo) | 95%CI | N | Median OS (mo) | 95%CI | P-value | |

| Resection | No resection | ||||||

| Positive studies | |||||||

| Hackert et al[39] | 85 | 12.3 | NA | ||||

| Tachezy et al[38] | 69 | 14 | 10.8-18.2 | 69 | 7.5 | 4.9–10.2 | < 0.001 |

| Crippa et al[34] | 11 | 39 | 116 | 11 | < 0.0001 | ||

| Klein et al[33] | 22 | 16.6 | NA | ||||

| Yamada et al[75] | 11 | 10.1 | 28 | 6.8 | NS | ||

| Shrikhande et al[36] | 11 | 11.4 | 7.8-16.5 | 118 | 5.9 | 5.4-7.6 | 0.04 |

| Negative studies | |||||||

| Zanini et al[35] | 15 | 9.1 | 8.6-9.7 | NA | |||

| Dünschede et al[40] | 9 | 8 (4-16) | 5 | 11 (10-12) | |||

| Gleisner et al[37] | 22 | 5.9 | 66 | 5.6 | 0.46 | ||

| Takada et al[42] | 11 | 6 (2-10) | 33 | 3 (2-9) | |||

In a recently published retrospective multi-center analysis of six European centers consisting of 69 patients[38], the 5-year survival was 0% in the non-resection group versus 5.8% in the group that underwent combined liver and pancreas resection (median OS was 14.5 in resected group vs 7.5 mo in non resected group, P < 0.001).

Some studies have reported a dismal survival of 5.6-8 months for patients with adenocarcinoma of the pancreas who underwent synchronous liver resection[35,37,40,42]. Most of them died of recurrent disease within 12 mo of surgery[37,40]. Zanini et al[35] reported median disease free survival (DFS) of 5.2 mo for 11 patients with 57% having disease recurrence in liver. All patients had moderate or poorly differentiated pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Chemotherapy may play an important role in selection of patients for liver resection and also to downstage the tumour. Some series have suggested that response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy either radiological or biochemical (CA 19-9) may serve as a useful tool for careful selection of patients for aggressive surgery[34,39].

Crippa et al[34] reported an impressive median OS of 36 mo for 11 patients who underwent surgical resection and 11 mo in chemotherapy only group (n = 116), similar to median OS seen in FOLFIRINOX group in ACCORD11 trial[32]. In their study, patients were considered for liver metastasectomy only if they achieved complete or partial response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Seven percent had complete response and 37% had partial response to chemotherapy. The different chemotherapy regimen used were FOLFIRINOX, PEXG/PDXG: Cisplatin, capecitabine, gemcitabine plus either epirubicin (PEXG) or docetaxel (PDXG) and PEFG: Cisplatin, epirubicin, fluorouracil and gemcitabine.

In case series by Hackert et al[39], 85 out of 128 patients with liver metastases showed survival benefit of radical surgery with 5 year survival of 8.1%. Of these, 16% (n = 20) received neoadjuvant and 57% (n = 73) completed adjuvant chemotherapy. 79.5% received gemcitabine, 8.2% 5-fluorouracil and 12.3% other schemes. In a recent retrospective study[43], 24 out of 535 patients achieved complete radiological response of the liver metastatic lesions post neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The chemotherapy administered consisted of single-agent gemcitabine, combination of gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel or FOLFIRINOX regimen.

In general longer survival has been reported after resection of metachronous disease when compared to synchronous resection of liver metastases in pancreatic cancer and this may be a potential factor in patient selection[35,40,44]. Overall survival was better in metachronous group which was 11.4 mo against 8.5 mo for synchronous group[40].

Several case series determined prognostic factors associated with worse outcome however results differ. In some studies, independent predictors of OS for patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer included resection status, use of multiple agents of chemotherapy, reduction in CA 19-9 level less than 50% of baseline value and > 5 liver metastases[34,38,43]. In contrast other studies have not confirmed that survival is influenced by tumour location (head/body/tail), size and number of liver metastases, preoperative CA 19-9 levels and resection margin status[35,37,39,42].

Eight studies were identified with 110 patients. Two studies evaluated synchronous resection of the primary as well as metastatic liver lesions[37,45], 2 studies only included staged resection in their analysis[46,47] while remaining 3 studies evaluated efficacy of both synchronous and metachronous resection[13,48,49] (Tables 3 and 4). Few case series[46,48] have reported morbidity rate of 30%, infection being most common and post-operative mortality rate of 1%-21%[37,45,48]. About 60%-70% had disease recurrence mainly in liver[46-48].

| N | Age (yr) | No. and size of hepatic metastases | Treatment | Median OS (mo) | Mortality Rate | Survival rate % | |

| Kurosaki et al[47], 2011 | Distal bile duct (n = 7) Ampullary cancer (n = 6) | 65 ± 10 | Median no = 2 (1-3) Median size 3 cm (1.8-6 cm) | Adjuvant cisplatin + 5 FU or gemcitabine or S1 (n = 10) | Bile duct = 14 Ampullary = 20 | - | 5-yr = 44.9% |

| Bresadola et al[49], 2011 | Gall bladder (n = 5) Papilla of Vater (n = 3) Biliary tract (n = 1) | 56 (46-64) | - | - | Gall bladder = 5 (1-12) Papilla of Vater = 7 (5-71) Biliary tract = 17 | 3% | |

| de Jong et al[48], 2010 | Ampullary (n = 10) Duodenal (n = 5) Biliary (n = 5) Pancreas (n = 20) | 63.0 ± 10.6 | Median no 1(1-5) and median size 0.7 (0.2-5.9) | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (pancreatic n = 4 ampullary n = 2 duodenal n = 1) Adjuvant chemotherapy n = 22 (55%) Gemcitabine (n = 14) 5-fluruoracil (n = 4), cyclophosphamide (n = 2) Combination irinotecan (n = 3) | Intestinal type = 23 Pancreatobiliary = 13 | 5% | 3-yr survival Intestinal tumours = 33% Pancreatobiliary tumours = 8% |

| Wakai et al[45], 2008 | Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; adeno- carcinoma (n = 2) Gall bladder; adeno-squamous (n = 1) | 63 (35-79) | - | - | Bile duct = 8 and 15 gall Bladder = 9 | 21% | 5 yr = Extra hepatic 12% Gall bladder 9% |

| Gleisner et al[37], 2007 | Ampullary (n = 1) Duodenal (n = 2) Distal bile duct (n = 2) Histology Adenocarcinoma | 65(53–82) | Median no = 1 and median size 0.6 cm (0.3-1.2) | FOLFIRI given to duodenal cancer | 9.9 | 9.10% | 3 yr = 6.7% |

| Adam et al[13], 2006 | Ampullary (n = 15) Pancreatic (n = 41) Gallbladder (n = 23) Biliary (n = 5) | 53 (10-87) | - | - | Ampullary = 38 | - | 5 yr Ampullary = 46% The entire cohort = 27% |

| Fuji et al[46], 1999 | Bile duct (n = 2) (adenocarcinoma) Ampulla of vater (n = 2) Duodenal cancer (n = 3) | 58 (36-67) | Median no = 1 | - | 20 | - | 3 yr = 28% |

| N | Median OS (mo) | 95%CI | N | Median OS (mo) | 95%CI | |

| Resection | No resection or palliative surgery | |||||

| Positive studies | ||||||

| Fujii et al[46] | 7 | 20 | NA | |||

| Kurosaki et al[47] | 13 | 28-60 | 9 | 6-12 | ||

| Niguma et al[50] | 10 | 17.2 | 12 | 4.4 | ||

| de Jong et al[48] | 8 | 17-19 | 7 | 7 | < 0.01 | |

| Adam et al[13] | 15 | 38 | NA | |||

| Negative studies | ||||||

| Gleisner et al[37] | 5 | 9.9 | 6 | 0.43 | ||

| Wakai et al[45] | 3 | 9 | NA | |||

| Bresadola et al[49] | 7 | 15 | NA | |||

In a study from Japan, 10 out of 64 patients who underwent radical resection for gall bladder cancer with liver metastases, had median survival of 17.2 mo, in contrast to 4.4 mo in palliative surgery group (n = 12) and 7 mo in non-curative resection group[50]. Fujii et al[46] reported an impressive survival of 3 years for patients with periampullary carcinoma (n = 7; cholangiocarcinoma n = 2, ampulla of vater n = 2, duodenal cancer n = 3) following liver resection who had longer interval between treatment of primary cancer with pancreatoduodenectomy and occurrence of solitary liver lesion. Some studies failed to show any survival benefit with hepatectomy for biliary tract cancers[37,45,49]. The median survival ranged from 5 to 15 mo with 3 years survival rate of 6%[37] and 5-year survival rates lower than 20%[45] after liver resection.

The only prospective study by Kurosaki et al[47] showed that hepatectomy for a solitary metastasis in distal common bile duct cancer and ampulla of vater cancer was associated with improved overall survival of 44.9% at 5 years compared to patients with unresectable liver disease with shorter survival rate of less than 2 years. 13 patients underwent liver resection for metachronous liver metastases for adenocarcinoma of distal cholangiocarcinoma (n = 7) and adenocarcinoma of ampullary cancer (n = 6). In subgroup analysis, patients with solitary lesion, R0 resection and who received adjuvant chemotherapy consisting of cisplatin + 5 fluorouracil or gemcitabine or S1 benefitted the most with longer overall survival. Whereas those with multiple hepatic lesions, R1 resection and did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy had early tumour recurrence and a short survival period of less than 2 years following the operation. The pattern of re-recurrence after hepatectomy was favoured the remnant liver.

In some studies resection of liver metastasis proved advantageous in a subset of patients with intestinal-type tumours compared to those with pancreatobiliary lesions. de Jong et al[48] analysed patients by tumour origin and by presentation (synchronous vs metachronous). Among the 40 patients in the study, 50% had pancreatic cancer (n = 20), with fewer patients having an ampullary (n = 10), duodenal (n = 5) or biliary (n = 5) tumour. 5-fluorouracil, gemcitabine and irinotecan based regimens was offered as neoadjuvant therapy to 7 patients and adjuvant treatment to 22 patients. Survival was affected by tumour origin. Specifically, patients with a pancreatobiliary tumour (i.e., pancreas or distal cholangiocarcinoma) had worse survival compared with patients with intestinal-type tumours (i.e., ampullary or duodenal); 23 mo vs 13 mo, respectively; P = 0.05; 3 years survival of 33% vs 8%). Post-operative mortality was only 5% in contrast to other studies.

Similar findings were reported by Adam et al[13] where in a cohort of patients with ampullary primary tumours that presented with metachronous liver disease, benefitted the most from resection with 5-year overall rate of 46% compared to those with pancreatic cancer with 5-year survival rate of 27%. For biliary tract cancers, survival was not affected by number or size of liver metastases and disease presentation (synchronous or metachronous)[48] but tumour origin had a major effect on long-term outcome[13,48]. Survival benefit was seen in patients with longer duration of disease free survival between primary surgery and occurrence of solitary liver lesion[13,46], with R0 resection and received chemotherapy[47].

Recent progress in systemic therapy may play a role in increasing surgical options. In particular for pancreatic cancer response rates have increased from under 10% to now over 30% in some trials. FOLFIRINOX[32] and gemcitabine with nab paclitaxel[51] have substantial activity in metastatic PDAC with response rate of 31% and 23%. Furthermore, these regimens may convert a substantial number into resectable tumours. Few case series have demonstrated efficacy of these regimen in locally advanced and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer[52,53]. With FOLFIRINOX, overall response rate reported range from 30% to 50%[54,55], resection rates 40%-50%[56-58] with 40%-90% having R0 resection[57-59]. In similar patient groups gemcitabine and nab paclitaxel, has a response rate of 30%[60,61] with resection rate of 56% and R0 resection rate of 80%[61].

New treatment modalities are being evaluated using genomics-driven precision medicine for advanced pancreatic ductal carcinoma. COMPASS is a prospective study which showed that patients with an “unstable” genomic subtype responded well to m-FOLFIRINOX while tumours that displayed basal-like RNA expression signature were chemotherapy resistant[62]. Pancreatic cancer tissues have a higher expression of CD40 as compared to adjacent normal tissues. A combination of CD40 agonist antibody with gemcitabine showed tumour regression in advanced PDAC with liver metastasis[63].

Similarly in biliary tract cancer, gemcitabine and cisplatin is now the treatment of choice in metastatic setting with response rate of 36%[64]. A retrospective analysis also evaluated the activity of gemcitabine-platinum-based regimen in 37 locally advanced gall bladder cancer patients showing an overall response rate (ORR) of 67.5% with 17 patients (46%) that underwent R0 resection[65].

Unlike pancreatic cancer, clinical data have suggested an encouraging future for targeting checkpoint pathways in biliary tract tumours[66]. A phase 1b trial using PDL1 inhibitor monotherapy for PDL1 positive advanced biliary tract cancers (BTC) demonstrated modest antitumor activity with an overall response rate of 17.4% with 4 patients having a partial response[67]. An additional group of BTC with mismatch-repair deficiency have shown impressive durable responses with checkpoint inhibitor therapy in a phase 2 study. Four cases of BTC had an objective response in 71% and PFS in 67% of these patients to pembrolizumab[68]. There are clinical trials that are using combination immunotherapy or immunotherapy with chemotherapy in advanced biliary tract cancers. Like pancreatic cancer, genomic alterations in BTC may serve as biomarkers in predicting response to chemotherapy and immunotherapy[69].

Development of more efficacious approaches for pancreatic cancer treatment would require identification of biomarkers that can predict the response and toxicity to various therapeutic agents. In this regard, the predictive value of CA 19-9 was demonstrated in a retrospective cohort study[39]. It was suggested that CA 19-9 predicts resectability as well as survival in PDAC patients. Highly elevated preoperative or increasing postoperative CA 19-9 levels were associated with low resectability and poor survival rates. Recently, pharmacogenomics profiling of circulating tumour and invasive cells (CTICs) isolated from patients with PDAC was evaluated as a predictor of tumour response, progression, and resistance[70].

As 95% of PDACs harbour KRAS mutations (mKRAS), circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) has potential utility in this setting. Recent study demonstrated that positive ctDNA KRAS in metastatic disease has been associated with lower PFS and OS[71]. In a study by McDuff et al[72], undetectable preoperative ctDNA following neoadjuvant treatment for locally advanced pancreatic cancer is associated good surgical outcome. This approach is worthy of further study also in stage 4 setting for incorporating ctDNA with the goal of improving patient selection for surgery.

The resection of the primary tumour and synchronous liver metastases is not recommended under current national and international guidelines for the treatment of PDAC and survival data at this time for hepatic resection of metastatic pancreatobiliary adenocarcinomas is mixed.

PDAC represents one of the most aggressive tumours with a poor prognosis with 5-year survival of 1% in stage 4. The liver is the most common site of metastatic disease[73]. Currently, the standard of care for PDAC patients with stage IV disease is systemic therapy with palliative intent. Surgical resection is hardly ever considered.

The studies on the surgical management of PDAC liver metastasis are all retrospective studies involving a small number of patients without well-defined indications for resection. The analysed groups were heterogeneous and information on parameters, such as the general condition of the patients, comorbidities, tumour-related symptoms and quality-of-life were also lacking. Few studies lacked control groups. In few case series of liver metastasectomy, the median overall survival was comparable in the patients who under underwent liver resection to that achieved with the standard chemotherapy regimen for stage 4 PDAC without surgery.

Regrettably, most studies were conducted long time back and did not include chemotherapy as part of neoadjuvant strategy. Also most studies did not include details of utilized chemotherapy regimens and the combination of FOLFIRINOX and metastasectomy has yet to be evaluated. The significantly higher response rate of this regimen and the increasing experience of its use in down-staging prior to resection may see a greater role for selected liver resection.

Despite these limitations, the data inferred from all the trials suggests that hepatic resection can be safe and may be appropriate for highly selected PDAC patients with a propensity towards improved outcomes and provide a chance for long term survival. A longer survival has been reported for patients who underwent curative intent surgery after neoadjuvant gemcitabine and with use of FOLFIRINOX or combination of gemcitabine and nab Paclitaxel, better response rate can be achieved with promising results as demonstrated in in the setting of locally advanced PDAC. Bile duct cancer and gallbladder cancer are aggressive diseases with poor prognosis with median survival time of 8-11 mo with chemotherapy in advanced setting[64,74].

The evidence to support liver resection for biliary tract tumour is even more limited due to the paucity of cases of surgical treatment of biliary carcinoma, the diversity of surgical procedures and the surgical outcomes of the procedure have not been adequately analysed. In all the studies, there was no defined control group and lack of standard chemotherapy may have impacted long term outcome.

Adams et al[13], Kurosaki et al[47] and de Jong et al[48] revealed that liver metastasis from duodenal or ampullary-origin tumour was accompanied by improved survival after surgery as compared with that from pancreatobiliary tumour with an impressive 5-year overall rate of 46%. This needs to be interpreted with caution due to small study population in each study. However this finding seems to reflect the differences in the behaviour of the primary tumour with periampullary cancers having better prognosis than pancreatic cancers. Promising outcomes of conversion pancreatectomy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer has been reported with better treatment regimens consisting of either chemotherapy or immunotherapy or combination and this may be a major change in the future. Multi-institutional prospective trials are required to fully delineate the potential therapeutic utility and operative indications of liver metastasectomy in the setting of modern interdisciplinary management of hepatobiliary tract tumours. The use of neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy with FOLFIRINOX or combination of gemcitabine and nab Paclitaxel for pancreatic cancer and with cisplatin and gemcitabine for gall bladder, cholangiocarcinoma and ampullary cancer in setting of synchronous or metachronous liver metastases should be standardized to avoid confounding results.

The disease free interval between primary tumour diagnosis and the discovery of a metachronous liver metastases and response to the neoadjuvant treatment may also facilitate the selection of patients with more favourable tumour biology and prognosticate individual patient. Incorporation of genomic profiling in clinical practice should be carried out for improved patient stratification and treatment selection. Furthermore the use of liquid biopsies and assessment of ctDNA may have a major role here in allowing selection of patients with the lowest risk of systemic involvement being considered for surgical intervention.

Hepatic resection is safe and can be effective, with outcomes mainly dependent on primary tumour site and histology. Hence a decision for a resection must be made on a highly individual basis and is multifactorial, including the, age, performance status, favourable tumour biology, valid prognostic markers, local resectability patient preference and the individual risk of complications. Application of a possible statistical model based on key prognostic factors may provide further guidance for better patient selection for curative liver resection by predicting long-term survivals. Further prospective, adequately powered studies with appropriate control arms are warranted for external validation of existing prognostic markers for more accurate selection, stratification of patients for these procedures and confirm the benefit of hepatic metastasectomy for selected group of patients.

Hepatic metastasectomy is well established for colorectal and neuroendocrine cancer with survival benefit. The overall prognosis for advanced pancreas and biliary tract cancers remains dismal. The resection of the primary tumour and synchronous liver metastases is not recommended under current national and international guidelines for the treatment of stage 4 pancreatobiliary cancer and survival data at this time for hepatic resection under such circumstances is mixed.

The studies on the surgical management of pancreatobiliary liver metastasis are all retrospective studies involving a small number of patients. There are inconsistent results with regards to benefit of liver metastasectomy on overall survival. Hence why we conducted extensive literature review to analyse and consolidate findings from all the studies to evaluate the safety and feasibility of liver metastasectomy in setting of stage 4 pancreatic and biliary tract cancers.

This paper showed that resection of liver metastases in pancreatic and biliary cancers may provide survival benefit without compromising safety and quality of life in a very select group of patients. Patients with metachronous liver metastases and with good response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy derived the most benefit. However most studies included in our review were conducted long time back and did not include chemotherapy as part of neoadjuvant strategy or used biomarkers to select patients. Evolution of new neoadjuvant systemic treatment such as FOLFIRINOX and immunotherapy may have significant potential to downstage cancers to potentially resectable state. This coupled with increased safety of liver resections and discovery of potential biomarkers can aid in better population selection for resection of metastatic disease under such circumstances, with hope to improve the survival outcome.

Our review highlights the need for multi-institutional prospective trials to fully delineate the potential therapeutic utility of liver metastasectomy for hepatobiliary tract tumours in era of modern systemic treatment and for further validation of prognostic markers used for patient selection. Comprehensive genomic profiling and use of ctDNA should also be considered for improved patient stratification and treatment selection.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: Australia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Andrianello S, Rungsakulkij N, Sperti C, Yang F S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Tan WW

| 1. | Namasivayam S, Martin DR, Saini S. Imaging of liver metastases: MRI. Cancer Imaging. 2007;7:2-9. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 158] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Belghiti J, Hiramatsu K, Benoist S, Massault P, Sauvanet A, Farges O. Seven hundred forty-seven hepatectomies in the 1990s: an update to evaluate the actual risk of liver resection. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:38-46. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 800] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 778] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jarnagin WR, Gonen M, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, Ben-Porat L, Little S, Corvera C, Weber S, Blumgart LH. Improvement in perioperative outcome after hepatic resection: analysis of 1,803 consecutive cases over the past decade. Ann Surg. 2002;236:397-406; discussion 406-407. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1148] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1030] [Article Influence: 46.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Abdalla EK, Vauthey JN, Ellis LM, Ellis V, Pollock R, Broglio KR, Hess K, Curley SA. Recurrence and outcomes following hepatic resection, radiofrequency ablation, and combined resection/ablation for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg. 2004;239:818-825; discussion 825-827. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1364] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1235] [Article Influence: 61.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Aloia TA, Vauthey JN, Loyer EM, Ribero D, Pawlik TM, Wei SH, Curley SA, Zorzi D, Abdalla EK. Solitary colorectal liver metastasis: resection determines outcome. Arch Surg. 2006;141:460-466; discussion 466-467. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 314] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 313] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Taniai N, Yoshida H, Mamada Y, Matsumoto S, Mizuguchi Y, Suzuki H, Furukawa K, Akimaru K, Tajiri T. Outcome of surgical treatment of synchronous liver metastases from colorectal cancer. J Nippon Med Sch. 2006;73:82-88. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tomizawa N, Ohwada S, Ogawa T, Tanahashi Y, Koyama T, Hamada K, Kawate S, Sunose Y. Factors affecting the prognosis of anatomical liver resection for liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006;53:89-93. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Wei AC, Greig PD, Grant D, Taylor B, Langer B, Gallinger S. Survival after hepatic resection for colorectal metastases: a 10-year experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:668-676. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 287] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Que FG, Nagorney DM, Batts KP, Linz LJ, Kvols LK. Hepatic resection for metastatic neuroendocrine carcinomas. Am J Surg. 1995;169:36-42; discussion 42-43. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 273] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chen H, Hardacre JM, Uzar A, Cameron JL, Choti MA. Isolated liver metastases from neuroendocrine tumors: does resection prolong survival? J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:88-92; discussion 92-93. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 236] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chamberlain RS, Canes D, Brown KT, Saltz L, Jarnagin W, Fong Y, Blumgart LH. Hepatic neuroendocrine metastases: does intervention alter outcomes? J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:432-445. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 461] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 492] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nave H, Mössinger E, Feist H, Lang H, Raab H. Surgery as primary treatment in patients with liver metastases from carcinoid tumors: a retrospective, unicentric study over 13 years. Surgery. 2001;129:170-175. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 126] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Adam R, Chiche L, Aloia T, Elias D, Salmon R, Rivoire M, Jaeck D, Saric J, Le Treut YP, Belghiti J. Hepatic resection for noncolorectal nonendocrine liver metastases: analysis of 1,452 patients and development of a prognostic model. Ann Surg. 2006;244:524-535. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 144] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | O’Rourke TR, Tekkis P, Yeung S, Fawcett J, Lynch S, Strong R, Wall D, John TG, Welsh F, Rees M. Long-term results of liver resection for non-colorectal, non-neuroendocrine metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:207-218. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 73] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Reddy SK, Barbas AS, Marroquin CE, Morse MA, Kuo PC, Clary BM. Resection of noncolorectal nonneuroendocrine liver metastases: a comparative analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:372-382. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 68] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Clarke NAR, Kanhere HA, Trochsler MI, Maddern GJ. Liver resection for non-colorectal non-neuroendocrine metastases. ANZ J Surg. 2018;88:E313-E317. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fitzgerald TL, Brinkley J, Banks S, Vohra N, Englert ZP, Zervos EE. The benefits of liver resection for non-colorectal, non-neuroendocrine liver metastases: a systematic review. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2014;399:989-1000. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Buell JF, Rosen S, Yoshida A, Labow D, Limsrichamrern S, Cronin DC, Bruce DS, Wen M, Michelassi F, Millis JM. Hepatic resection: effective treatment for primary and secondary tumors. Surgery. 2000;128:686-693. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Earle SA, Perez EA, Gutierrez JC, Sleeman D, Livingstone AS, Franceschi D, Levi JU, Robbins C, Koniaris LG. Hepatectomy enables prolonged survival in select patients with isolated noncolorectal liver metastasis. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:436-446. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Elias D, Cavalcanti de Albuquerque A, Eggenspieler P, Plaud B, Ducreux M, Spielmann M, Theodore C, Bonvalot S, Lasser P. Resection of liver metastases from a noncolorectal primary: indications and results based on 147 monocentric patients. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:487-493. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 151] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ercolani G, Grazi GL, Ravaioli M, Ramacciato G, Cescon M, Varotti G, Del Gaudio M, Vetrone G, Pinna AD. The role of liver resections for noncolorectal, nonneuroendocrine metastases: experience with 142 observed cases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:459-466. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 114] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Weitz J, Blumgart LH, Fong Y, Jarnagin WR, D’Angelica M, Harrison LE, DeMatteo RP. Partial hepatectomy for metastases from noncolorectal, nonneuroendocrine carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2005;241:269-276. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 158] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yedibela S, Gohl J, Graz V, Pfaffenberger MK, Merkel S, Hohenberger W, Meyer T. Changes in indication and results after resection of hepatic metastases from noncolorectal primary tumors: a single-institutional review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:778-785. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 64] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lu F, Poruk KE, Weiss MJ. Surgery for oligometastasis of pancreatic cancer. Chin J Cancer Res. 2015;27:358-367. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lindell G, Gunnarsdottir K, Rizell M, Norén A, Isaksson B, Ardnor B, Sandström P. Survival after resection for non-colorectal liver metastases – As good as for colorectal metastases – A national registry based study (SweLiv). HPB. 2016;18:e9-e10. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Tapia Rico G, Townsend AR, Klevansky M, Price TJ. Liver metastases resection for gastric and esophageal tumors: is there enough evidence to go down this path? Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2016;16:1219-1225. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Adam R, Delvart V, Pascal G, Valeanu A, Castaing D, Azoulay D, Giacchetti S, Paule B, Kunstlinger F, Ghémard O. Rescue surgery for unresectable colorectal liver metastases downstaged by chemotherapy: a model to predict long-term survival. Ann Surg. 2004;240:644-657; discussion 657-658. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 746] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 885] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Pozzo C, Basso M, Cassano A, Quirino M, Schinzari G, Trigila N, Vellone M, Giuliante F, Nuzzo G, Barone C. Neoadjuvant treatment of unresectable liver disease with irinotecan and 5-fluorouracil plus folinic acid in colorectal cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:933-939. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 216] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Delaunoit T, Alberts SR, Sargent DJ, Green E, Goldberg RM, Krook J, Fuchs C, Ramanathan RK, Williamson SK, Morton RF. Chemotherapy permits resection of metastatic colorectal cancer: experience from Intergroup N9741. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:425-429. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 130] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Masi G, Vasile E, Loupakis F, Cupini S, Fornaro L, Baldi G, Salvatore L, Cremolini C, Stasi I, Brunetti I. Randomized trial of two induction chemotherapy regimens in metastatic colorectal cancer: an updated analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:21-30. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 137] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Folprecht G, Gruenberger T, Bechstein WO, Raab HR, Lordick F, Hartmann JT, Lang H, Frilling A, Stoehlmacher J, Weitz J. Tumour response and secondary resectability of colorectal liver metastases following neoadjuvant chemotherapy with cetuximab: the CELIM randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:38-47. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 704] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 683] [Article Influence: 45.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouché O, Guimbaud R, Bécouarn Y, Adenis A, Raoul JL, Gourgou-Bourgade S, de la Fouchardière C. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817-1825. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4838] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5100] [Article Influence: 392.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Klein F, Puhl G, Guckelberger O, Pelzer U, Pullankavumkal JR, Guel S, Neuhaus P, Bahra M. The impact of simultaneous liver resection for occult liver metastases of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:939350. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 51] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Crippa S, Bittoni A, Sebastiani E, Partelli S, Zanon S, Lanese A, Andrikou K, Muffatti F, Balzano G, Reni M. Is there a role for surgical resection in patients with pancreatic cancer with liver metastases responding to chemotherapy? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:1533-1539. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 87] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Zanini N, Lombardi R, Masetti M, Giordano M, Landolfo G, Jovine E. Surgery for isolated liver metastases from pancreatic cancer. Updates Surg. 2015;67:19-25. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Shrikhande SV, Kleeff J, Reiser C, Weitz J, Hinz U, Esposito I, Schmidt J, Friess H, Büchler MW. Pancreatic resection for M1 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:118-127. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 159] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Gleisner AL, Assumpcao L, Cameron JL, Wolfgang CL, Choti MA, Herman JM, Schulick RD, Pawlik TM. Is resection of periampullary or pancreatic adenocarcinoma with synchronous hepatic metastasis justified? Cancer. 2007;110:2484-2492. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 113] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Tachezy M, Gebauer F, Janot M, Uhl W, Zerbi A, Montorsi M, Perinel J, Adham M, Dervenis C, Agalianos C. Synchronous resections of hepatic oligometastatic pancreatic cancer: Disputing a principle in a time of safe pancreatic operations in a retrospective multicenter analysis. Surgery. 2016;160:136-144. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 100] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Hackert T, Niesen W, Hinz U, Tjaden C, Strobel O, Ulrich A, Michalski CW, Büchler MW. Radical surgery of oligometastatic pancreatic cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43:358-363. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 126] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Dünschede F, Will L, von Langsdorf C, Möhler M, Galle PR, Otto G, Vahl CF, Junginger T. Treatment of metachronous and simultaneous liver metastases of pancreatic cancer. Eur Surg Res. 2010;44:209-213. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 41. | Klempnauer J, Ridder GJ, Piso P, Pichlmayr R. [Is liver resection in metastases of exocrine pancreatic carcinoma justified?]. Chirurg. 1996;67:366-370. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 42. | Takada T, Yasuda H, Amano H, Yoshida M, Uchida T. Simultaneous hepatic resection with pancreato-duodenectomy for metastatic pancreatic head carcinoma: does it improve survival? Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44:567-573. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 43. | Frigerio I, Regi P, Giardino A, Scopelliti F, Girelli R, Bassi C, Gobbo S, Martini PT, Capelli P, D’Onofrio M. Downstaging in Stage IV Pancreatic Cancer: A New Population Eligible for Surgery? Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:2397-2403. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 74] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Michalski CW, Erkan M, Hüser N, Müller MW, Hartel M, Friess H, Kleeff J. Resection of primary pancreatic cancer and liver metastasis: a systematic review. Dig Surg. 2008;25:473-480. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 78] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Wakai T, Shirai Y, Tsuchiya Y, Nomura T, Akazawa K, Hatakeyama K. Combined major hepatectomy and pancreaticoduodenectomy for locally advanced biliary carcinoma: long-term results. World J Surg. 2008;32:1067-1074. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Fujii K, Yamamoto J, Shimada K, Kosuge T, Yamasaki S, Kanai Y. Resection of liver metastases after pancreatoduodenectomy: report of seven cases. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:2429-2433. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 47. | Kurosaki I, Minagawa M, Kitami C, Takano K, Hatakeyama K. Hepatic resection for liver metastases from carcinomas of the distal bile duct and of the papilla of Vater. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396:607-613. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | de Jong MC, Tsai S, Cameron JL, Wolfgang CL, Hirose K, van Vledder MG, Eckhauser F, Herman JM, Edil BH, Choti MA. Safety and efficacy of curative intent surgery for peri-ampullary liver metastasis. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:256-263. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Bresadola V, Rossetto A, Adani GL, Baccarani U, Lorenzin D, Favero A, Bresadola F. Liver resection for noncolorectal and nonneuroendocrine metastases: results of a study on 56 patients at a single institution. Tumori. 2011;97:316-322. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Niguma T, Mimura T, Kojima T. Aggressive surgery to gallbladder cancer - is hepatectomy for gallbladder cancer only for negative margin? HPB. 2012;14:288–699. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 51. | Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, Chiorean EG, Infante J, Moore M, Seay T, Tjulandin SA, Ma WW, Saleh MN. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1691-1703. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4035] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4332] [Article Influence: 393.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Christians KK, Tsai S, Mahmoud A, Ritch P, Thomas JP, Wiebe L, Kelly T, Erickson B, Wang H, Evans DB. Neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX for borderline resectable pancreas cancer: a new treatment paradigm? Oncologist. 2014;19:266-274. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 158] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Tinchon C, Hubmann E, Pichler A, Keil F, Pichler M, Rabl H, Uggowitzer M, Jilek K, Leitner G, Bauernhofer T. Safety and efficacy of neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX treatment in a series of patients with borderline resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Acta Oncol. 2013;52:1231-1233. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Kim SS, Nakakura EK, Wang ZJ, Kim GE, Corvera CU, Harris HW, Kirkwood KS, Hirose R, Tempero MA, Ko AH. Preoperative FOLFIRINOX for borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: Is radiation necessary in the modern era of chemotherapy? J Surg Oncol. 2016;114:587-596. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Gunturu KS, Yao X, Cong X, Thumar JR, Hochster HS, Stein SM, Lacy J. FOLFIRINOX for locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer: single institution retrospective review of efficacy and toxicity. Med Oncol. 2013;30:361. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 93] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Hosein PJ, Macintyre J, Kawamura C, Maldonado JC, Ernani V, Loaiza-Bonilla A, Narayanan G, Ribeiro A, Portelance L, Merchan JR. A retrospective study of neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX in unresectable or borderline-resectable locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:199. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 185] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Blazer M, Wu C, Goldberg RM, Phillips G, Schmidt C, Muscarella P, Wuthrick E, Williams TM, Reardon J, Ellison EC. Neoadjuvant modified (m) FOLFIRINOX for locally advanced unresectable (LAPC) and borderline resectable (BRPC) adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1153-1159. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 178] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Turner K, Narayanan S, Attwood K, Hochwald SN, Iyer RV, Kukar M. Neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX and/or gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel for advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:473-473. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Marsh RW, Baker M, Catenacci DVT, Kozloff M, Polite BN, Posne MC, Roggin KK, Talamonti MS, Kindler HL. Peri-operative modified FOLFIRINOX (mFOLFIRINOX) in resectable pancreatic cancer (PDAC): A pilot study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:312-312. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Alvarez-Gallego R, Cubillo A, Garralda E, Vega E, Rodriguez-Pascual R, Ugidos L. Pathological response to neoadjuvant gemcitabine plus nabpaclitaxel in pancreatic adenocarcinoma to improve survival. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:4109-4109. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 61. | Alvarez-Gallego R, Cubillo A, Rodriguez-Pascual J, Quijano Y, De Vicente E, Garcia L, Morelli MP, Hidalgo M. Antitumor activity of nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine in resectable pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4040-4040. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 62. | Aung KL, Fischer SE, Denroche RE, Jang GH, Dodd A, Creighton S, Southwood B, Liang SB, Chadwick D, Zhang A. Genomics-Driven Precision Medicine for Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: Early Results from the COMPASS Trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:1344-1354. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 333] [Article Influence: 47.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Beatty GL, Chiorean EG, Fishman MP, Saboury B, Teitelbaum UR, Sun W, Huhn RD, Song W, Li D, Sharp LL. CD40 agonists alter tumor stroma and show efficacy against pancreatic carcinoma in mice and humans. Science. 2011;331:1612-1616. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1152] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1212] [Article Influence: 93.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, Madhusudan S, Iveson T, Hughes S, Pereira SP. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1273-1281. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2617] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2754] [Article Influence: 196.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Sirohi B, Mitra A, Jagannath P, Singh A, Ramadvar M, Kulkarni S, Goel M, Shrikhande SV. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced gallbladder cancer. Future Oncol. 2015;11:1501-1509. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Blair AB, Murphy A. Immunotherapy as a treatment for biliary tract cancers: A review of approaches with an eye to the future. Curr Probl Cancer. 2018;42:49-58. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Bang YJ, Doi T, De Braud F, Piha-Paul S, Hollebecque A, Abdul Razak AR, Lin CC, Ott PA, He AR, Yuan SS. Safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab (MK-3475) in patients (pts) with advanced biliary tract cancer: interim results of KEYNOTE-028. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:s112. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 105] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Kemberling H, Eyring AD, Skora AD, Luber BS, Azad NS, Laheru D. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509-2520. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6096] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6542] [Article Influence: 726.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Lee H, Ross JS. The potential role of comprehensive genomic profiling to guide targeted therapy for patients with biliary cancer. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10:507-520. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Yu KH, Ricigliano M, Hidalgo M, Abou-Alfa GK, Lowery MA, Saltz LB, Crotty JF, Gary K, Cooper B, Lapidus R. Pharmacogenomic modeling of circulating tumor and invasive cells for prediction of chemotherapy response and resistance in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:5281-5289. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Krantz BA, Tsui D, Lowery MA, Capanu M, Yu KH, Kelsen DP, Gedvilaite E, Zhang L, Selcuklu SD, You D. Plasma KRAS as a biomarker for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). J Clin Oncol. 2018;36 (suppl 4); 316. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 72. | McDuff S, Parikh AP, Hazar-Rethinam M, Zheng H, Van Seventer E, Nadres B, Ryan DP, Weekes CD, Clark JW, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Using circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) to predict surgical outcome after neoadjuvant chemoradiation for locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC). J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:272. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 73. | Katz MH, Wang H, Fleming JB, Sun CC, Hwang RF, Wolff RA, Varadhachary G, Abbruzzese JL, Crane CH, Krishnan S. Long-term survival after multidisciplinary management of resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:836-847. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 353] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 370] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Williams KJ, Picus J, Trinkhaus K, Fournier CC, Suresh R, James JS, Tan BR. Gemcitabine with carboplatin for advanced biliary tract cancers: a phase II single institution study. HPB (Oxford). 2010;12:418-426. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Yamada S, Fujii T, Sugimoto H, Kanazumi N, Kasuya H, Nomoto S, Takeda S, Kodera Y, Nakao A. Pancreatic cancer with distant metastases: a contraindication for radical surgery? Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:881-885. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |