Published online Oct 16, 2017. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i10.529

Peer-review started: April 10, 2017

First decision: May 16, 2017

Revised: May 24, 2017

Accepted: June 30, 2017

Article in press: July 3, 2017

Published online: October 16, 2017

Cap polyposis is a rare intestinal disorder. Characteristic endoscopic findings are multiple inflammatory polypoid lesions covered by caps of fibrous purulent exudate. Although a specific treatment has not been established, some studies have suggested that eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is effective. We report a case of a 20-year-old man with cap polyposis presenting with hematochezia. Colonoscopy showed the erythematous polyps with white caps from the sigmoid colon to rectum. Histopathological findings revealed elongated, tortuous, branched crypts lined by hyperplastic epithelium with a mild degree of fibromusculosis in the lamina propria. Although H. pylori eradication was instituted, there was no improvement over six months. We then performed en bloc excision of the polyps by endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), which resulted in complete resolution of symptoms. ESD may be a treatment option for cap polyposis refractory to conservative treatments. We review the literature concerning treatment for cap polyposis and clinical outcomes.

Core tip: Although for cap polyposis, conservative treatment should be selected as first-line therapy, the optimal treatment of cap polyposis refractory to conservative treatment has not been established. Endoscopic submucosal dissection may be a treatment option for cases refractory to conservative treatment.

- Citation: Murata M, Sugimoto M, Ban H, Otsuka T, Nakata T, Fukuda M, Inatomi O, Bamba S, Kushima R, Andoh A. Cap polyposis refractory to Helicobacter pylori eradication treated with endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(10): 529-534

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v9/i10/529.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v9.i10.529

Cap polyposis is a rare intestinal disorder with unique clinical, endoscopic, and histological findings. Clinical symptoms include mucoid and bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, tenesmus, weight loss, and dysplasia. Endoscopy typically reveals multiple reddish, mucus-capped inflammatory polyps in the rectosigmoid area with normal mucosa interspersed between the polyps[1]. Pathologically, the surfaces of these inflammatory polyps are covered by a thick layer of fibrinopurulent exudate, hence the term “cap”[1]. However, the etiology of cap polyposis is unclear and its clinical course varies from spontaneous clinical and endoscopic remission without treatment[2-4] to persistent disease refractory to conservative treatment[5-7], requiring surgical resection. Little is known about its long-term course.

The optimal treatment for cap polyposis has not been established[2-16]. Some cases have been treated successfully by the avoidance of straining at defecation[8], antimicrobial agents (i.e., metronidazole)[9], steroids[2], immunomodulators (i.e., infliximab)[12], endoscopic therapy[13,14] and surgical resection[5-7]. Recently, the efficacy of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication therapy for H. pylori-positive patients with cap polyposis has been reported[10,11,15,16], and in 2016 the Japanese Society for Helicobacter Research added cap polyposis as a possible H. pylori-associated disease in its treatment guidelines. However, no treatments for H. pylori-negative cap polyposis or H. pylori-positive cases refractory to eradication therapy have yet been established.

Here, we report a case of H. pylori-negative cap polyposis refractory to H. pylori eradication therapy that was successfully treated with endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). We also review the literature concerning conservative and endoscopic treatments for cap polyposis.

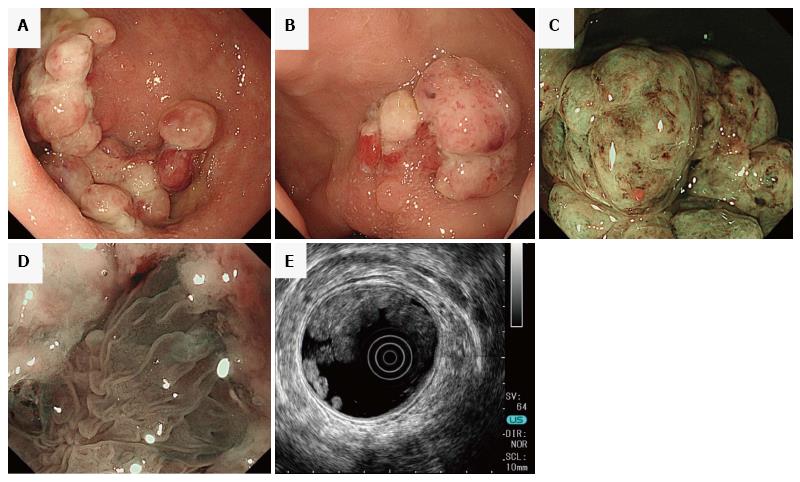

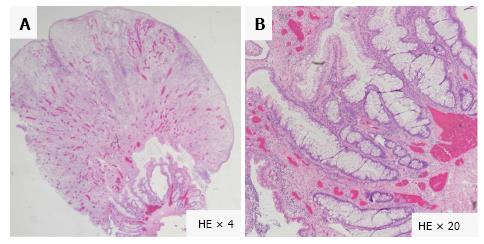

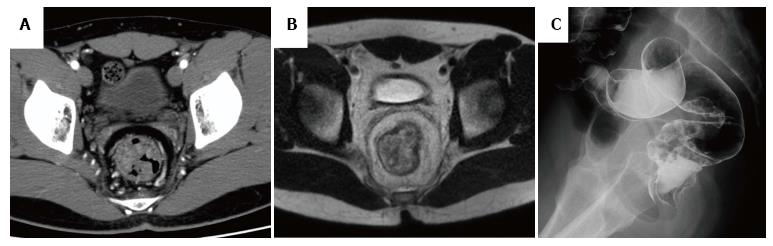

A 20-year-old Japanese man presented with a 1-year history of hematochezia and tenesmus. He denied straining at stool and had no history of anal prolapse. His past medical and family history were unremarkable. Laboratory tests revealed mild hypoproteinemia (serum albumin 3.9 g/L), but no hepatic or renal dysfunction, leukocytosis, elevation of C-reactive protein, or anemia. Colonoscopy revealed the characteristic appearance of cap polyposis, with approximately 20-30 erythematous variform inflammatory polyps with white caps of fibrinopurulent exudate from the sigmoid colon to the rectum (Figure 1A and B). Magnification endoscopy with narrow-band imaging showed amorphous exudate in the white caps overlying long branching tortuous crypts in the basal part of the polyps (Figure 1C and D). Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) with radial array scanning showed significant thickening of the mucosa without evidence of invasion into the submucosa (Figure 1E). Histologic findings from a polyp revealed elongated, tortuous, branched crypts lined with hyperplastic epithelium with inflammatory cell infiltration and a mild degree of fibromusculosis in the lamina propria (Figure 2). The surface of the polyps was covered by thick inflammatory granulation tissue with exudate (Figure 2). The intervening mucosa between lesions was histologically normal. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging showed multiple elevated lesions thickening the walls of the sigmoid colon and rectum (Figure 3A and B). Barium enema showed multiple raised mucosal lesions without stenosis or sclerotic changes in the sigmoid colon and rectum (Figure 3C). The differential diagnosis included the mucosal prolapse syndrome, inflammatory polyps, colon cancer, malignant lymphoma, inflammatory bowel disease, and adenomatous polyposis. We diagnosed cap polyposis based on the endoscopic and histopathological characteristics.

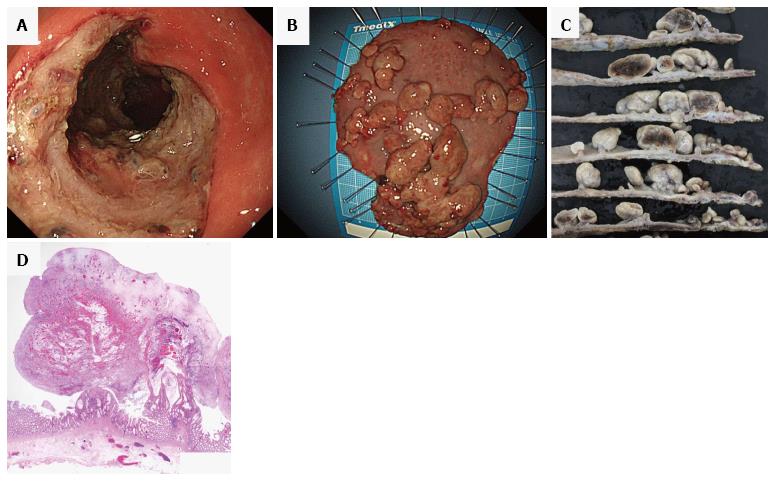

The patient had no evidence of H. pylori infection by urea breath test, anti-H. pylori antibody, or endoscopic findings (i.e., gastric mucosal atrophy or diffuse redness of gastric mucosa). However, according to previous evidence that H. pylori eradication therapy was effective for patients with cap polyposis[10,11,15,16], H. pylori eradication therapy with vonoprazan 20 mg, amoxicillin 750 mg and clarithromycin 200 mg twice daily for 7 d was initiated. Abdominal symptoms (i.e., hematochezia and tenesmus), bowel habits, and endoscopic findings did not improve over the six months after therapy. Therefore, as conservative alternative treatment, we performed en bloc excision of the polyps with ESD (Figure 4). After resection, the patient’s symptoms disappeared and he had no endoscopic evidence of recurrence for six months.

We report a case of a patient with cap polyposis refractory to H. pylori eradication therapy who then underwent en bloc excision of polyps by ESD with good results. This is the first report of the efficacy of ESD for treatment of cap polyposis. More studies of ESD as a treatment option for cap polyposis are needed to validate its use instead of surgical resection.

Cap polyposis can be difficult to diagnose. It can resemble mucosal prolapse syndrome (MPS). There has been a debate about whether cap polyposis is a specific form of inflammatory disorder or part of a spectrum of MPS[12]. MPS and cap polyposis share some clinical, endoscopic, and histological features. Both diseases show infiltration of inflammatory cells with elongated stroma and fibromuscular obliteration of the lamina propria. However, the fibromuscular obliteration is more marked in cap polyposis. MPS is usually confined to the rectum, but cap polyposis usually involves the sigmoid and/or descending colon as well as the rectum. EUS findings in cap polyposis show significant thickening of the mucosa[9], whereas MPS is characterized by smooth, diffuse thickening of the submucosa and minimal thickening of the lamina propria[17].

Common clinical features of cap polyposis are hematochezia (82%), chronic straining (64%), and mucous diarrhea (46%)[1]. When mucous diarrhea is severe and/or continuous for long periods, excessive protein loss is observed as a result[1,5]. Direct loss of protein was demonstrated in a case of cap polyposis by scintigraphy with technetium 99m-labeled diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid complexed to human serum albumin[18]. In our case, blood tests revealed mild hypoproteinemia, with an albumin level 39 g/L, possibly secondary to protein loss from mucous diarrhea.

Cap polyposis has been attributed to colonic dysmotility, immune abnormalities, bacterial infection (i.e., H. pylori) or other unknown pathogens. Géhénot et al[19] suggested the possibility of bacterial infection, reporting on a cap polyposis patient who had no evidence of colonic dysmotility and who was successfully treated with metronidazole. Of the myriad gut microbiota, although H. pylori is not detected in mucosa obtained from cap polyposis lesions[10], most cases of cap polyposis with H. pylori infection have resolved after H. pylori eradication therapy[10,11,15,16,18]. H. pylori infection is well-known to cause not only gastroduodenal diseases, but also diseases such as idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura and chronic idiopathic urticaria[20,21]. In addition, eradication therapy often induces regression of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma in the rectum and thyroid[22]. Although an H. pylori-associated immune reaction may play a role in the development of some cases of cap polyposis, there is no evidence for efficacy of H. pylori eradication therapy in H. pylori-negative cap polyposis patients, as in our case. Because the development of cap polyposis with active inflammation in the colonic mucosa may be related to other bacterial infections that are also sensitive to the antimicrobial agents used in H. pylori eradication therapy (i.e., clarithromycin, amoxicillin, and metronidazole), we selected eradication therapy as the first-line treatment. Although eradication failed to cure the cap polyposis, further studies will be required to investigate whether other pathogens are related to this diagnosis, and whether their eradication can effect resolution.

The efficacy of endoscopic treatment, such as polypectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), for cap polyposis has been reported[12,14]. However, en bloc excision is difficult to perform with conventional EMR, and the use of surgical resection is more frequent[5-7]. Although there have been no reports of malignant transformation, surgical resection may be excessive for the treatment of cap polyposis. We consider ESD en bloc excision to be less invasive, and also can prevent recurrence.

ESD, an endoscopic procedure that originated in Japan and Korea in the late 1990s which has since spread rapidly to other nations, is now commonly used to treat gastrointestinal tumors[23,24]. ESD allows complete pathological assessment, proving this technique superior to polypectomy or conventional EMR to prevent recurrence[25]. To date, no case of cap polyposis treated with ESD has been reported. Our present case suggests that ESD may be an effective treatment for intractable cap polyposis, with lower invasiveness than surgical resection. Our patient remains under surveillance for recurrence.

For cap polyposis, conservative treatment should be selected as first-line therapy. In particular, we recommend eradication therapy for H. pylori infection. To our knowledge, however, the optimal treatment of cap polyposis refractory to conservative medical treatment has not been established. This is the first report of cap polyposis refractory to conservative medical treatment effectively treated with ESD. We believe that ESD is less invasive and more effective than surgical resection in cases refractory to conservative treatment. ESD may be a treatment option for cap polyposis cases refractory to conservative medical treatments, such as H pylori eradication, metronidazole, steroids, and infliximab. Further investigation is required.

A 20-year-old Japanese man with cap polyposis located in sigmoid colon and rectum refractory to Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication and resected with endoscopic submucosal dissection.

Cap polyposis.

Although the differential diagnosis includes the mucosal prolapse syndrome (MPS), inflammatory polyps, colon cancer, malignant lymphoma, inflammatory bowel disease, and adenomatous polyposis, MPS is most possible disease as differentiation disease, because cap polyposis and MPS share some clinical, endoscopic, and histological features.

Although mild hypoproteinemia was revealed, there was no hepatic or renal dysfunction, leukocytosis, elevation of C-reactive protein, or anemia.

Colonoscopy revealed the characteristic appearance of cap polyposis, with approximately 20-30 erythematous variform inflammatory polyps with white caps of fibrinopurulent exudate from the sigmoid colon to the rectum.

Pathological findings revealed elongated, tortuous, branched crypts lined with hyperplastic epithelium with inflammatory cell infiltration and a mild degree of fibromusculosis in the lamina propria in the polypoid lesion and thick inflammatory granulation tissue in the surface of the polyps.

Because this case was refractory to H. pylori eradication as the first-line therapy, en bloc excision of polyposis with endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) was selected as second-line therapy.

Previously, although endoscopic treatment including polypectomy and EMR, and conservative medical treatments including H. pylori eradication, metronidazole, steroids, and infliximab, had been reported, the optimal treatment for cap polyposis has not been established.

ESD may be a treatment option for cap polyposis cases refractory to conservative treatments (i.e., H. pylori eradication, metronidazole, steroids, and infliximab).

The paper is well written.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Zamani M S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Ng KH, Mathur P, Kumarasinghe MP, Eu KW, Seow-Choen F. Cap polyposis: further experience and review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1208-1215. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chang HS, Yang SK, Kim MJ, Ye BD, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, Kim JH. Long-term outcome of cap polyposis, with special reference to the effects of steroid therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:211-216. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sasaki Y, Takeda H, Fujishima S, Sato T, Nishise S, Abe Y, Ajioka Y, Kawata S, Ueno Y. Nine-year follow-up from onset to spontaneous complete remission of cap polyposis. Intern Med. 2013;52:351-354. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Ohkawara T, Kato M, Nakagawa S, Nakamura M, Takei M, Komatsu Y, Shimizu Y, Takeda H, Sugiyama T, Asaka M. Spontaneous resolution of cap polyposis: case report. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:599-602. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gallegos M, Lau C, Bradly DP, Blanco L, Keshavarzian A, Jakate SM. Cap polyposis with protein-losing enteropathy. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011;7:415-420. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Konishi T, Watanabe T, Takei Y, Kojima T, Nagawa H. Confined progression of cap polyposis along the anastomotic line, implicating the role of inflammatory responses in the pathogenesis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:446-447; discussion 447. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Campbell AP, Cobb CA, Chapman RW, Kettlewell M, Hoang P, Haot BJ, Jewell DP. Cap polyposis--an unusual cause of diarrhoea. Gut. 1993;34:562-564. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Oriuchi T, Kinouchi Y, Kimura M, Hiwatashi N, Hayakawa T, Watanabe H, Yamada S, Nishihira T, Ohtsuki S, Toyota T. Successful treatment of cap polyposis by avoidance of intraluminal trauma: clues to pathogenesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2095-2098. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shimizu K, Koga H, Iida M, Yao T, Hirakawa K, Hoshika K, Mikami Y, Haruma K. Does metronidazole cure cap polyposis by its antiinflammatory actions instead of by its antibiotic action? A case study. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:1465-1468. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Akamatsu T, Nakamura N, Kawamura Y, Shinji A, Tateiwa N, Ochi Y, Katsuyama T, Kiyosawa K. Possible relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and cap polyposis of the colon. Helicobacter. 2004;9:651-656. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Oiya H, Okawa K, Aoki T, Nebiki H, Inoue T. Cap polyposis cured by Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:463-466. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bookman ID, Redston MS, Greenberg GR. Successful treatment of cap polyposis with infliximab. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1868-1871. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Arimura Y, Isshiki H, Hirayama D, Onodera K, Murakami K, Yamashita K, Shinomura Y. Polypectomy to eradicate cap polyposis with protein-losing enteropathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1689-1691. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Batra S, Johal J, Lee P, Hourigan S. Cap Polyposis Masquerading as Inflammatory Bowel Disease in a Child. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016; Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Takeshima F, Senoo T, Matsushima K, Akazawa Y, Yamaguchi N, Shiozawa K, Ohnita K, Ichikawa T, Isomoto H, Nakao K. Successful management of cap polyposis with eradication of Helicobacter pylori relapsing 15 years after remission on steroid therapy. Intern Med. 2012;51:435-439. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Suzuki H, Sato M, Akutsu D, Sugiyama H, Sato T, Mizokami Y. A case of cap polyposis remission by betamethasone enema after antibiotics therapy including Helicobacter pylori eradication. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2014;23:203-206. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Hizawa K, Iida M, Suekane H, Mibu R, Mochizuki Y, Yao T, Fujishima M. Mucosal prolapse syndrome: diagnosis with endoscopic US. Radiology. 1994;191:527-530. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nakagawa Y, Nagai T, Okawara H, Nakashima H, Tasaki T, Soma W, Hisamatsu A, Watada M, Murakami K, Fujioka T. Cap polyposis (CP) which relapsed after remission by avoiding straining at defecation, and was cured by Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Intern Med. 2009;48:2009-2013. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Géhénot M, Colombel JF, Wolschies E, Quandalle P, Gower P, Lecomte-Houcke M, Van Kruiningen H, Cortot A. Cap polyposis occurring in the postoperative course of pelvic surgery. Gut. 1994;35:1670-1672. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, Hamada F, Yoshida T, Yokota K, Okada H, Yamamoto K. Seventeen-year effects of eradicating Helicobacter pylori on the prevention of gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer; a prospective cohort study. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:638-644. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 64] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Gisbert JP, Kuipers EJ, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gasbarrini A, Atherton J, Graham DY. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2017;66:6-30. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1710] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1745] [Article Influence: 249.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Kalpadakis C, Pangalis GA, Vassilakopoulos TP, Kyriakaki S, Yiakoumis X, Sachanas S, Moschogiannis M, Tsirkinidis P, Korkolopoulou P, Papadaki HA. Clinical aspects of malt lymphomas. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2014;9:262-272. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Fujishiro M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for stomach neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5108-5112. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 63] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 70] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ninomiya Y, Oka S, Tanaka S, Nishiyama S, Tamaru Y, Asayama N, Shigita K, Hayashi N, Chayama K. Risk of bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors in patients with continued use of low-dose aspirin. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:1041-1046. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hull MJ, Mino-Kenudson M, Nishioka NS, Ban S, Sepehr A, Puricelli W, Nakatsuka L, Ota S, Shimizu M, Brugge WR. Endoscopic mucosal resection: an improved diagnostic procedure for early gastroesophageal epithelial neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:114-118. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |