Published online Jul 27, 2014. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v6.i7.520

Revised: April 11, 2014

Accepted: May 28, 2014

Published online: July 27, 2014

Processing time: 218 Days and 3.9 Hours

AIM: To study the safety and efficacy of pegylated interferon alfa-2b, indigenously developed in India, plus ribavirin in treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV).

METHODS: One-hundred HCV patients were enrolled in an open-label, multicenter trial. Patients were treated with pegylated interferon alfa-2b 1.5 μg/kg per week subcutaneously plus oral ribavirin 800 mg/d for patients with genotypes 2 and 3 for 24 wk. The same dose of peginterferon plus weight-based ribavirin (800 mg/d for ≤ 65 kg; 1000 mg/d for > 65-85 kg; 1200 mg/d for > 85-105 kg; 1400 mg/d for > 105 kg body weight) was administered for 48 wk for patients with genotypes 1 and 4. Serological and biochemical responses of patients were assessed.

RESULTS: Eighty-two patients (35 in genotypes 1 and 4 and 47 in 2 and 3), completed the study. In genotype 1, 25.9% of patients achieved rapid virologic response (RVR): while the figures were 74.1% for early virologic response (EVR) and 44.4% for sustained virologic response (SVR). For genotypes 2 and 3, all patients bar one belonged to genotype 3, and of those, 71.4%, 87.5%, and 64.3% achieved RVR, EVR, and SVR, respectively. In genotype 4, 58.8%, 88.2%, and 52.9% of patients achieved RVR, EVR, and SVR, respectively. The majority of patients attained normal levels of alanine aminotransferase by 4-12 wk of therapy. Most patients showed a good tolerance for the treatment, although mild-to-moderate adverse events were exhibited; only two patients discontinued the study medication due to serious adverse events (SAEs). Eleven SAEs were observed in nine patients; however, only four SAEs were related to study medication.

CONCLUSION: Peginterferon alfa-2b, which was developed in India, in combination with ribavirin, is a safe and effective drug in the treatment of HCV.

Core tip: In a multicenter study, the safety and efficacy of pegylated interferon alfa-2b, indigenously developed in India, plus ribavirin was evaluated on 100 hepatitis C virus (HCV) patients with genotypes 1, 2, 3, and 4. Eighty-two patients completed the study. Most patients had mild-to-moderate adverse events, although 11 serious adverse events were reported in 9 patients. However, only 4 of these were related to study medication. The percentage of serologic response (rapid virologic response, early virologic response, and sustained virologic response rates) of patients was similar to that reported in published studies. In conclusion, peginterferon alfa-2b, developed in India, is a safe and cost-effective drug in the treatment of Indian patients with HCV infection.

- Citation: Rao P, Koshy A, Philip J, Premaletha N, Varghese J, Narayanasamy K, Mohindra S, Pai NV, Agarwal MK, Konar A, Vora HB. Pegylated interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for treatment of chronic hepatitis C. World J Hepatol 2014; 6(7): 520-526

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v6/i7/520.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v6.i7.520

According to the World Health Organization’s estimates, over 170 million people (3% of the world’s population) are infected with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) worldwide[1]. Each year, about five million people are newly infected, and more than 350000 people, despite availability of treatment, die from HCV-related complications[2]. Hepatitis is an emerging infection in India, with a paucity of large scale prevalence studies on hepatitis C in the general population. The reported prevalence rates also vary widely (range 0.09% to 7.89%)[3]. However, regardless of prevalence rates, the burden of HCV infection in India is expected to be high with a population over 1.2 billion; as a result, its treatment modalities, as well as success rates, demand attention.

The HCV genotype plays a significant role in therapeutic guidelines, since HCV genotypes 1 and 4 are more resistant to treatment compared to HCV genotypes 2 and 3. Yet, irrespective of genotype, pegylated interferon, in combination with ribavirin, is considered the gold standard in the treatment of chronic HCV infection[4-7]. Currently, both pegylated interferon alfa-2a and pegylated alfa-2b are available in India. These drugs are exorbitantly priced and are not easily accessible to the majority of Indian patients. In view of this, Virchow Biotech developed pegylated interferon alfa-2b from Escherichia coli by using recombinant DNA technology, and priced it competitively. The aim of the present study is to evaluate the safety and efficacy of pegylated interferon alfa-2b in chronic hepatitis C patients.

Male and female patients aged 18-65 years-old (both years inclusive) that attended the outpatient department of 12 hospitals were screened. 100 consecutive patients were enrolled if they had chronic hepatitis C infection as per the following criteria: presence of HCV RNA and persistent elevation of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels 1.5 times greater than normal (N < 40 IU/L); compensated liver disease at the time of baseline visit as defined by Child-Pugh class A; hemoglobin ≥ 9 g/dL (females), ≥ 10 g/dL (males); platelet count ≥ 75 × 109/L; neutrophil count ≥ 1.5 × 109/L; and thyroid stimulating hormone within normal limits (0.35-5.50 mIU/mL). Only treatment näive patients were included in the study. Patients were excluded if they had evidence of other liver diseases such as hepatitis A virus, hepatitis B virus, alfa-2 antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson’s disease, primary biliary cirrhosis, autoimmune liver disease, or hemochromatosis. Other criteria for exclusion were: chronic alcoholism; history of drug abuse; immune suppression associated with organ transplantation; history of hypersensitivity to interferon or its diluents; significant psychiatric disease, especially depression; severe cardiovascular disease; patients with co-infection of human immunodeficiency virus infection; and pregnant and lactating women. Study procedures were explained to each participant and written informed consent was obtained before enrolment into the study.

This is an open-label, multicenter study that was conducted, with the approval of the Drugs Controller General of India, at 12 centers across eight Indian cities between March 2010 and March 2013. The study, conducted in accordance with principles under the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and later revisions, was initiated after obtaining approval of the study protocol from the institutional ethical committee at respective centers. This trial was registered in Clinical Trial Registry India (CTRI/2011/000028).

Treatment consisted of the administration of peginterferon alfa-2b (manufactured by Virchow Biotech Private Ltd, Hyderabad, India) 1.5 μg/kg per week subcutaneously, in combination with ribavirin 800 mg/d orally, for patients with genotypes 2 and 3 for 24 wk. The same dose of peginterferon was administered in combination with weight-based ribavirin (800 mg/d for ≤ 65 kg; 1000 mg/d for > 65-85 kg; 1200 mg/d for > 85-105 kg; 1400 mg/d for > 105 kg body weight) for 48 wk for patients with genotypes 1 and 4.

Ribavirin dose was reduced to half if hemoglobin level was < 10 g/dL; treatment was discontinued if hemoglobin level was < 8.5 g/dL. Peginterferon dose was reduced to half in patients with white blood cells (WBC) < 1.5 × 109/L, neutrophils < 0.75 × 109/L, or platelet count < 50 × 109/L. Peginterferon treatment was discontinued in patients with WBC < 1.0 × 109/L, neutrophils < 0.5 × 109/L, or platelet count < 25 × 109/L.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the percentage of patients with sustained virologic response (SVR), defined as undetectable serum HCV RNA 24 wk after cessation of therapy. Secondary efficacy endpoints were: rapid virologic response (RVR), defined as undetectable serum HCV RNA at week 4; early virologic response (EVR), defined as undetectable serum HCV RNA or 2-log10 reduction in HCV RNA from the baseline at week 12; end of treatment virologic response (ETVR), defined as undetectable serum HCV RNA at weeks 24 and 481; with normalization of ALT at weeks 12, 24, 481, and 24 after cessation of therapy (1only for patients with genotypes 1 and 4). Data on non-responders, relapse, and breakthrough were also collected[4]. Non-responders were defined as those who failed to clear HCV RNA from serum after 24 wk of therapy. Relapse was defined as undetectable HCV RNA at the end of treatment, followed by the reappearance of HCV RNA during follow-up. Breakthrough was defined as undetectable HCV RNA during treatment, followed by the appearance of HCV RNA, despite continued treatment.

Blood samples were obtained for serologic tests for quantitative HCV RNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) at baseline and at weeks 4, 12, 24, and 48 for genotypes 2 and 3; while for genotypes 1 and 4 this was at baseline and at weeks 4, 12, 24, 48, and 72. Cobas Taqman HCV test (Roche), using the real-time PCR method with a lower detection limit of < 25 IU/mL, was employed for quantification of HCV RNA in serum. A linear array detection kit from Roche was used in HCV genotyping.

Vitals (respiratory rate, pulse rate, body temperature, and blood pressure), hematology (complete blood picture, hemoglobin, and platelet count), and ALT levels were measured at each visit. Biochemical parameters (serum lactate dehydrogenase, creatinine, potassium, and phosphorus) were also measured at specified screening visits; weeks 4, 12, 24, and 48 for genotypes 2 and 3, and weeks 4, 12, 24, 48, and 72 for genotypes 1 and 4. Patients were monitored for adverse events (AE) and medication compliance throughout the duration of study. Adverse events were graded as mild, moderate, or severe. Treatment was suspended or modified according to the severity of adverse events. The dosage of peginterferon alfa-2b, ribavirin, or combination of the two was again increased to the original level after the resolution of adverse events. Serious adverse events (SAEs) were documented and communicated to the institutional ethics committee and Drugs Controller General of India.

Various trials conducted on patients with genotypes 1 and 4 or 2 and 3 have reported around 40%-80% SVR, which reflects the efficacy of peginterferon alfa-2b in the treatment of HCV[6,7]. In our earlier pilot study conducted on 25 patients with HCV infection, a SVR of 60% was observed. Considering the 60% efficacy, 95%CI, 80% power, and 15% error with a 15% dropout rate with two tailed t-test, the calculated sample size was 100 patients.

Values were expressed as mean (SD). Since an open-label study design was adopted, efficacy assessment basically relied upon descriptive statistics rather than inferential analysis. Intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was carried out on the population that included all patients who met the eligibility criteria and had received at least one dose of the investigational drug during the study period. Per protocol analysis was also carried out, which included patients who completed the stipulated study period.

Safety parameters, such as vital signs and laboratory findings including hematology and biochemical parameters, were analyzed by repeated measure analysis of variance. Two-sided P-values were reported, with those less than 0.05 being considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 19.0 for Windows.

A total of 100 consecutive patients with chronic hepatitis C who met the inclusion/exclusion criteria were enrolled into the study. Among them, 27 pertained to genotype 1, 17 for genotype 4, only one for genotype 2, and 55 for genotype 3. Since there was only one patient with genotype 2, the results presented on genotypes 2 and 3 basically represent only those of genotype 3. The demographic and baseline characteristics of the 100 enrolled patients are presented in Table 1. At baseline, values of hematological and biochemical investigations were within normal limits except for liver function tests such as serum ALT, aspartate aminotransferase, and alkaline phosphatase. Barring serum ALT levels, other demographic, hematological, and biochemical parameters, including HCV RNA levels, were not significantly different between genotypes 1, 3, and 4. The mean ALT levels in genotype 3 patients were significantly higher (P < 0.02) than those in genotype 1; but these were similar to those of genotype 4.

| Parameter | Genotype 1 | Genotype 3 | Genotype 4 |

| (n = 27) | (n = 56)1 | (n = 17) | |

| Age (yr) | 41.9 ± 13.2 | 41.7 ± 10.9 | 46.3 ± 9.3 |

| Weight (kg) | 60.5 ± 12.0 | 63.3 ± 11.5 | 63.7 ± 10.8 |

| Male number (%)2 | 19 (70.3%) | 11 (19.7%) | 11 (64.7%) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 14.1 ± 1.6 | 13.8 ± 1.9 | 14.2 ± 1.2 |

| White blood cell count (109/L) | 6682 ± 1682 | 7086 ± 1886 | 7201 ± 1886 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 58.4 ± 8.4 | 56.0 ± 11.8 | 53.3 ± 8.0 |

| Platelet count (103/L) | 200 ± 80 | 199 ± 78 | 170 ± 50 |

| Alanine Aminotransferase (U/L) | 88.1 ± 41 | 127.7 ± 87.4 | 104.9 ± 61.1 |

| HCV RNA log10 IU/mL | 5.5 ± 1.2 | 5.4 ± 1.1 | 5.5 ± 0.9 |

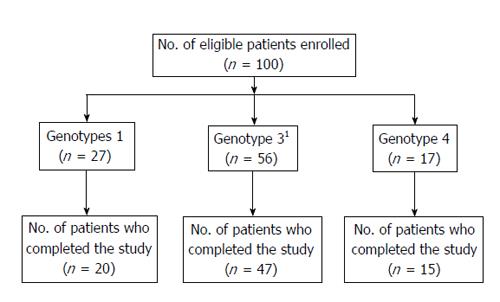

Figure 1 shows the flow of patients through the study. Among the 100 patients, 82 completed the study. Eighteen patients did not complete the study for the following reasons: lost to follow-up (8), withdrew (6), discontinued due to SAE (2), and discontinued therapy due to non-response by the investigator (2). Treatment compliance was monitored by maintaining a patient dairy. During the study period, the mean daily intake of ribavirin was 14.3 ± 1.84 mg/kg body weight in genotypes 1 and 4 and 12.84 ± 2.29 mg/kg body weight in genotype 3.

Overall, 57%, 84%, 72%, and 57% of enrolled patients achieved RVR, EVR, ETVR, and SVR, respectively. Results on virologic response of genotypes 1, 3, and 4, evaluated by ITT and per protocol analysis, are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

| Parameter | Genotype 1 | Genotype 31 | Genotype 4 |

| (n = 27) | (n = 56) | (n = 17) | |

| RVR | 25.9% | 71.4% | 58.8% |

| EVR | 74.1% | 87.5% | 88.2% |

| ETVR | 59.2% | 78.6% | 70.5% |

| SVR | 44.4% | 64.3% | 52.9% |

| Parameter | Genotype 1 | Genotype 31 | Genotype 4 |

| (n/N) | (n/N) | (n/N) | |

| RVR | 25.9% (7/27) | 74.1% (40/54) | 58.8% (10/17) |

| EVR | 74.1% (20/27) | 100% (49/49) | 88.2% (15/17) |

| ETVR | 84.2% (16/19) | 89.8% (44/49) | 75.0% (12/16) |

| SVR | 60.0% (12/20) | 76.6% (36/47) | 60.0% (9/15) |

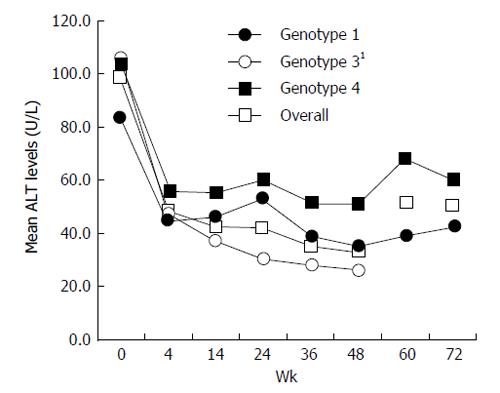

Data on the percentage of patients with normalization of ALT at weeks 4, 12, and 24 of treatment, at the end of treatment (week 48 in genotypes 1 and 4, and week 24 in genotypes 2 and 3), and at 24 wk after cessation of therapy are presented in Table 4. In general, the majority of patients, irrespective of their genotype, attained normal levels of ALT by 4 to 12 wk of therapy and the effect was sustained even during follow-up. Mean ALT levels during different study periods are presented in Figure 2.

| Weeks | Genotype 1 | Genotype 31 | Genotype 4 |

| (n = 27) | (n = 56) | (n = 17) | |

| 4 | 16 (59.2) | 27 (48.2) | 8 (47.0) |

| 12 | 17 (62.9) | 29 (51.7) | 8 (47.0) |

| 24 | 17 (62.9) | 35 (62.5) | 9 (52.9) |

| 48 | 17 (62.9) | 40 (71.4) | 11 (64.7) |

| 72 | 17 (62.9) | - | 12 (70.6) |

The majority of patients tolerated the scheduled treatment with peginterferon and ribavirin, though with the usual known adverse events with these drugs. Adverse events were analyzed for safety of peginterferon alfa-2b and presented in Table 5. Ninety-one patients reported 328 adverse events; 95 events by genotype 1 patients, 68 events by genotype 4 patients, and 165 events in genotype 3 patients. Administration of peginterferon alfa-2b resulted in common mild-to-moderate AEs, which included flu-like symptoms, nausea, and loss of appetite. None of the patients permanently stopped treatment due to adverse events, with the exception of two patients who discontinued due to SAEs. Ribavirin was temporarily discontinued due to anemia in ten patients. Twenty-four patients required ribavirin dose reduction, four needed peginterferon alfa-2b dose reduction, and four required both ribavirin and peginterferon alfa-2b dose reduction for management of anemia and thrombocytopenia. Nine patients reported 11 SAEs, which were all relieved with relevant therapy aside from one patient who died. Among the 11 SAEs, four were related to the study medication and the remaining seven, including the case of death, were unrelated to it.

| Adverse event | n (%) of patients | ||

| Genotype 1 | Genotype 31 | Genotype 4 | |

| (n = 27) | (n = 56) | (n = 17) | |

| Injection-site reactions | 9 (33.3) | 16 (28.6) | 7 (41.2) |

| Flu-like symptoms | 24 (88.8) | 49 (87.5) | 14 (82.3) |

| Tiredness | 4 (14.8) | 5 (8.9) | 2 (11.7) |

| Weight loss | 1 (3.7) | 3 (5.4) | 1 (5.8) |

| Chest discomfort | 1 (3.7) | 2 (3.6) | 2 (11.7) |

| Arthralgia | 3 (11.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.8) |

| Alopecia | 2 (7.4) | 10 (17.9) | 3 (17.6) |

| Anorexia | 2 (7.4) | 7 (12.5) | 3 (17.6) |

| Nausea | 3 (11.1) | 8 (14.3) | 3 (17.6) |

| Vomiting | 2 (7.4) | 3 (5.4) | 0 |

| Dyspepsia | 1 (3.7) | 3 (5.4) | 2 (11.7) |

| Gastritis | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Mucous stool | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 1 (3.7) | 4 (7.1) | 1 (5.8) |

| Melena | 1 (3.7) | 6 (10.7) | 0 |

| Ascites | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 2 (7.4) | 5 (8.9) | 1 (5.8) |

| Anemia | 9 (33.3) | 13 (23.2) | 6 (35.3) |

| Neutropenia | 12 (44.4) | 15 (26.8) | 8 (47.0) |

| Anxiety | 1 (3.7) | 3 (5.4) | 1 (5.8) |

| Depression | 2 (7.4) | 4 (7.1) | 3 (17.6) |

| Insomnia | 1 (3.7) | 1 (1.8) | 2 (11.7) |

| Hypothyroidism | 2 (7.4) | 2 (3.6) | 2 (11.7) |

| Giddiness | 1 (3.7) | 1 (1.8) | 2 (11.7) |

| Dry throat | 1 (3.7) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0) |

| Cough | 2 (7.4) | 2 (3.6) | 2 (11.7) |

| Sinusitis | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Bleeding gums | 2 (7.4) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0) |

| Palpitation | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pruritus | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.8) |

| Yellow-colored sputum | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.8) |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Death | 0 (0) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0) |

| No. of patients reporting AEs | 24 (88.8) | 49 (87.5) | 14 (82.3) |

| Discontinued due to SAEs | 0 (0) | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0) |

| Temporary discontinuation of therapy | 4 (14.8) | 3 (5.4) | 3 (17.6) |

| Temporary dose reduction | 11 (40.7) | 16 (29.6) | 5 (29.4) |

Infection with HCV is one of the most important medical and public health problems worldwide in view of its life-threatening complications, including hepatocellular carcinoma, cirrhosis, and liver failure[8-10]. The goal of therapy in chronic HCV infection is to achieve SVR and thereby prevent long-term complications. Despite the promising role of new antiviral therapies[11], the use of pegylated-interferon alfa combined with ribavirin continues, to date, to be the standard care of treatment in HCV infection.

Since genotype constitutes one of the important determinants of the course and outcome of therapy, 24 or 48 wk combination therapy with peginterferon alfa and ribavirin has been recommended for genotypes 2 and 3 and genotypes 1 and 4 patients, respectively[4-7]. The present open-label, multicenter study using standard-of-care therapy was undertaken to establish that the safety and efficacy of peginterferon alfa-2b is comparable to the results of historical controls in the treatment of chronic HCV infection.

One-hundred eligible patients with chronic HCV infection were enrolled, with the majority (55%) having HCV genotype 3 which is in accordance with the published prevalence studies conducted in India[12,13]. There was only one patient with genotype 2, which is rare among Indians, and thus it should be noted that the reported combined results of patients with genotypes 2 and 3, in fact, only reflects those of genotype 3. Anticipating 15% attrition, 100 patients were enrolled. However, there was instead an 18% dropout, and as a result, 82 patients completed the specified study period of therapy.

Since the dose and duration of therapy were different, the data on outcome measurements were analyzed separately for genotypes 1 and 4 and for genotypes 2 and 3. The SVR (44.4%) observed in the present study for genotype 1 is comparable with those of reported studies[14-16]. In genotypes 2 and 3, 64.3% of patients achieved SVR, which fits with the conformity figure results reported by Manns et al[17]. The rates of SVR in treatment naïve genotype 2 patients were reported to be 86.5%[18], which is higher than that of genotype 3. Since our genotype 2 and 3 patients, except for one, belonged to genotype 3, a lower SVR (64.3%) was observed in the present study. In genotype 4, 52.9% patients achieved SVR, which is comparable with values from published studies[19,20]. Apart from genotype, baseline viral load has been shown to be one of the determinants of SVR[21]. However, perhaps due to the small number of patients covered in the present study, our stratified statistical analysis showed that baseline viral load had no impact on SVR.

In view of the cost factor and incidence of adverse events with peginterferon use during long-duration treatment, individualized treatment, based on the results of RVR and EVR, has been emphasized. In this respect, the presence of RVR is highly predictive of ultimate SVR with a full treatment course of 48 wk in genotype 1 patients[22]. In the current study, all genotype 1 patients (n = 7) who achieved RVR also attained SVR; while a study reported a SVR rate of 86.8% in patients with RVR[15]. In genotype 4 patients, 80% with RVR attained SVR, whereas the published study reported 86%[23]. Similarly, among the genotype 3 patients who had RVR, 83.3% attained SVR, which is similar (83.7%) to that reported in the literature[24]. This further confirms the utility of RVR in predicting SVR.

Among the patients who attained EVR, 10 (76.9%) in genotype 1 and 9 (75%) in genotype 4 achieved SVR. In patients with genotypes 2 and 3, the percentage with EVR attaining SVR was 100%. This is in line with the literature[25], which shows that patients with genotype 3 who fail to achieve EVR also fail to achieve SVR. Since the duration of treatment for genotypes 2 and 3 is only 24 wk, it has been reported that EVR testing is not cost-effective in these patients[25]. This indicates that utility of RVR is higher than EVR in the prediction of SVR.

Overall, 16 patients had relapse; 5 (31.2%) patients in genotype 1, 8 (18.2%) patients in genotypes 2 and 3, and 3 (25%) patients in genotype 4. Among the 100 patients, 5 were non-responders to the study treatment; 1 (3.7%) patient in genotype 1; 2 (3.6%) patients in genotypes 2 and 3, and 2 (11.7%) in genotype 4. In addition 4 patients had breakthrough during the treatment; 2 (7.4%) patients in genotype 1; 1 (1.8%) patient in genotype 3, and 1 (5.8%) patient in genotype 4.

Biochemical response of peginterferon alfa-2b was assessed by the percentage of patients attaining normalization of ALT levels. Overall, the majority of patients (51%) had normalization of ALT levels as early as week 4. This denotes that peginterferon is very effective in producing a biochemical response in patients with chronic hepatitis C.

The treatment was well-tolerated in the majority of patients, though with the common side-effects usually attributed with interferon or ribavirin. In 32% of patients, temporary dose modifications in peginterferon (4%), ribavirin (24%), or both (4%), and temporary discontinuation of therapy in 10% of patients, were required. Though 11 SAEs were observed in 9 patients, only 4 were related to study medication, with such SAEs also being reported in earlier studies[15,17,26,27].

The limitations of the study are that it is a single arm study and the results on the outcome measures were compared with those of historical controls. Earlier studies on Indian patients with HCV infection were conducted using peginterferon alfa-2b in two studies-one study was carried out on 103 patients, but only on genotype 3 patients[25]; the other study, despite covering all four genotypes, had only 16 patients[28]. We are not aware of any study conducted with an adequately powered sample of Indian patients with HCV infection following the global guidelines on peginterferon plus ribavirin[4-7,29].

Therefore, despite the limitation of a lack of comparator, our results on serological responses such as RVR, EVR, ETVR, and SVR provide valuable information on the safety and efficacy of peginterferon alfa-2b, in combination with ribavirin, in the treatment of Indian patients with chronic HCV infection. Currently, Virchow Biotech-developed peginterferon alfa-2b is marketed in India and other emerging countries at a very competitive rate. In view of the relatively low incidence of the adverse events and improved virologic and biochemical response, the results of the study show that peginterferon alfa-2b, in combination with ribavirin, is a safe and cost-effective drug in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a major cause of chronic liver disease in India, with a high morbidity and mortality due to its complications. Pegylated interferon, in combination with ribavirin, is the standard recommended treatment for chronic hepatitis C. One of the reasons for this could be due to its cost factor, with another being that studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of these drugs in India are limited. Therefore, an attempt is being made to evaluate the efficacy of peginterferon alfa-2b, a drug locally developed in India, in combination with ribavirin.

This prospective study presents results on the efficacy, in terms of virologic response, of indigenously-developed peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin in Indian patients with different genotypes of chronic hepatitis C. Adverse events observed with this combination are also reported.

There have been a few prior studies on Indian patients with HCV infection using peginterferon alfa-2b. However, these were limited to a small number of patients or confined to one genotype.

This study demonstrates that virologic response of peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin, when given as per global guidelines in Indian patients with different types of chronic hepatitis C, is similar to that of historical controls.

Success rate of treatment is assessed based on sustained virologic response, which is defined as undetectable HCV RNA in blood 24 wk after cessation of therapy.

This is a straightforward clinical control study.

P- Reviewer: Ford N, Kanda T, Liu CJ, Shi Z S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: Rutherford A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Global surveillance and control of hepatitis C. Report of a WHO Consultation organized in collaboration with the Viral Hepatitis Prevention Board, Antwerp, Belgium. J Viral Hepat. 1999;6:35-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 512] [Cited by in RCA: 478] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | WHO. Hepatitis C. WHO Fact sheet No 164. Available from: http: //www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en/. |

| 3. | Mukhopadhyaya A. Hepatitis C in India. J Biosci. 2008;33:465-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49:1335-1374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2320] [Cited by in RCA: 2238] [Article Influence: 139.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2011;55:245-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 889] [Cited by in RCA: 919] [Article Influence: 65.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Omata M, Kanda T, Yu ML, Yokosuka O, Lim SG, Jafri W, Tateishi R, Hamid SS, Chuang WL, Chutaputti A. APASL consensus statements and management algorithms for hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatol Int. 2012;6:409-435. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ghany MG, Nelson DR, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. An update on treatment of genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C virus infection: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2011;54:1433-1444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 803] [Cited by in RCA: 834] [Article Influence: 59.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kenny-Walsh E. Clinical outcomes after hepatitis C infection from contaminated anti-D immune globulin. Irish Hepatology Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1228-1233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 658] [Cited by in RCA: 649] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Di Bisceglie AM. Natural history of hepatitis C: its impact on clinical management. Hepatology. 2000;31:1014-1018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Barrera JM, Bruguera M, Ercilla MG, Gil C, Celis R, Gil MP, del Valle Onorato M, Rodés J, Ordinas A. Persistent hepatitis C viremia after acute self-limiting posttransfusion hepatitis C. Hepatology. 1995;21:639-644. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Kanda T, Imazeki F, Yokosuka O. New antiviral therapies for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatol Int. 2010;4:548-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hissar SS, Goyal A, Kumar M, Pandey C, Suneetha PV, Sood A, Midha V, Sakhuja P, Malhotra V, Sarin SK. Hepatitis C virus genotype 3 predominates in North and Central India and is associated with significant histopathologic liver disease. J Med Virol. 2006;78:452-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Narahari S, Juwle A, Basak S, Saranath D. Prevalence and geographic distribution of Hepatitis C Virus genotypes in Indian patient cohort. Infect Genet Evol. 2009;9:643-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, Goodman ZD, Koury K, Ling M, Albrecht JK. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4736] [Cited by in RCA: 4554] [Article Influence: 189.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mangia A, Minerva N, Bacca D, Cozzolongo R, Ricci GL, Carretta V, Vinelli F, Scotto G, Montalto G, Romano M. Individualized treatment duration for hepatitis C genotype 1 patients: A randomized controlled trial. Hepatology. 2008;47:43-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kainuma M, Furusyo N, Kajiwara E, Takahashi K, Nomura H, Tanabe Y, Satoh T, Maruyama T, Nakamuta M, Kotoh K. Pegylated interferon α-2b plus ribavirin for older patients with chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4400-4409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Manns M, Zeuzem S, Sood A, Lurie Y, Cornberg M, Klinker H, Buggisch P, Rössle M, Hinrichsen H, Merican I. Reduced dose and duration of peginterferon alfa-2b and weight-based ribavirin in patients with genotype 2 and 3 chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2011;55:554-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kanda T, Imazeki F, Azemoto R, Yonemitsu Y, Mikami S, Kita K, Takashi M, Sunaga M, Wu S, Nakamoto S. Response to peginterferon-alfa 2b and ribavirin in Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 2. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:3335-3342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Al-Ali J, Siddique I, Varghese R, Hasan F. Pegylated interferon-alpha2b plus ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 4 infection in patients with normal serum ALT. Ann Hepatol. 2012;11:186-193. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Khuroo MS, Khuroo MS, Dahab ST. Meta-analysis: a randomized trial of peginterferon plus ribavirin for the initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C genotype 4. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:931-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hadziyannis SJ, Sette H, Morgan TR, Balan V, Diago M, Marcellin P, Ramadori G, Bodenheimer H, Bernstein D, Rizzetto M. Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: a randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:346-355. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Poordad F, Landaverde C. Rapid virological response to peginterferon alfa and ribavirin treatment of chronic hepatitis C predicts sustained virological response and relapse in genotype 1 patients. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2009;2:91-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kamal SM, El Kamary SS, Shardell MD, Hashem M, Ahmed IN, Muhammadi M, Sayed K, Moustafa A, Hakem SA, Ibrahiem A. Pegylated interferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin in patients with genotype 4 chronic hepatitis C: The role of rapid and early virologic response. Hepatology. 2007;46:1732-1740. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Poordad FF. Review article: the role of rapid virological response in determining treatment duration for chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:1251-1267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gralewicz S, Eckersdorf B, Gołebiewski H. Hippocampal rhythmic slow activity (RSA) in the cat after intraseptal injections of muscarinic cholinolytics. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars). 1992;52:211-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 596] [Cited by in RCA: 575] [Article Influence: 26.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Jacobson IM, Brown RS, Freilich B, Afdhal N, Kwo PY, Santoro J, Becker S, Wakil AE, Pound D, Godofsky E. Peginterferon alfa-2b and weight-based or flat-dose ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C patients: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2007;46:971-981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sood A, Midha V, Hissar S, Kumar M, Suneetha PV, Bansal M, Sood N, Sakhuja P, Sarin SK. Comparison of low-dose pegylated interferon versus standard high-dose pegylated interferon in combination with ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C with genotype 3: an Indian experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:203-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ray G, Pal S, Nayyar I, Dey S. Efficacy and tolerability of pegylated interferon alpha 2b and ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C--a report from eastern India. Trop Gastroenterol. 2007;28:109-112. [PubMed] |

| 29. | WHO. Guidelines for the screening, care and treatment of persons with hepatitis c infection. Available from: http: //apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/111747/1/9789241548755_eng.pdf?ua=1. |