Published online Jul 27, 2019. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i7.607

Peer-review started: March 20, 2019

First decision: April 23, 2019

Revised: May 20, 2019

Accepted: June 27, 2019

Article in press: June 27, 2019

Published online: July 27, 2019

Wilson disease (WD) is a rare copper metabolism disorder with symptoms including hepatic disorders, neuropsychiatric abnormalities, Kayser-Fleischer rings, and hemolysis in association with acute liver failure (ALF). Osteoarthritis is a rare manifestation of WD. We experienced a case of WD with arthritic pain in the knee and liver cirrhosis. Here, we report the clinical course in a WD patient with arthritic pain and liver cirrhosis receiving combination therapy with Zn and a chelator and discuss the cause of arthritic pain.

We present an 11-year-old boy who developed osteoarthritis symptoms and ALF, with a New Wilson Index Score (NWIS) of 12. He was diagnosed with WD with decreased serum ceruloplasmin and copper levels, increased urinary copper excretion, and ATP7B gene mutations detected on gene analysis. There was improvement in the liver cirrhosis, leading to almost normal liver function and liver imaging, one year after receiving combination therapy with Zn and a chelator. Moreover, his arthritic pain transiently deteriorated but eventually improved with a decrease in the blood alkaline phosphatase levels following treatment.

Patients with WD who develop ALF with an NWIS > 11 may survive after treatment with Zn and chelators, without liver transplantation, when they present with mild hyperbilirubinemia and stage ≤ II hepatic encephalopathy. Osteoarthritis symptoms may improve with long-term Zn and chelator therapy without correlation of liver function in WD.

Core tip: We present an 11-year-old boy with Wilson disease (WD) who developed osteoarthritis symptoms and acute liver failure, with a New Wilson Index Score (NWIS) of 12. His liver cirrhosis improved, leading to almost normal liver function and liver imaging results, one year after receiving combination therapy with Zn and a chelator. Patients with WD with a NWIS > 11 may be able to survive with treatment with Zn and chelators, without liver transplantation, in cases wherein they present with mild hyperbilirubinemia and stage ≤ II hepatic encephalopathy. Symptoms of associated osteoarthritis may also improve with long-term Zn and chelator therapy.

- Citation: Kido J, Matsumoto S, Sugawara K, Nakamura K. Wilson disease developing osteoarthritic pain in severe acute liver failure: A case report. World J Hepatol 2019; 11(7): 607-612

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v11/i7/607.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v11.i7.607

Wilson disease (WD) is a rare copper metabolism disorder caused by a mutation in the ATP7B gene, with a prevalence of 1 in 30000 to 1 in 100000 individuals. The clinical manifestations are secondary to accumulation of copper in various organs, with typical symptoms of hepatic disorders, neuropsychiatric abnormalities, Kayser-Fleischer (K-F) rings, and hemolysis in association with acute liver failure (ALF). WD may rarely present with extrahepatic conditions, such as skeletal abnormalities, including premature osteoporosis and arthritis[1], cardiomyopathy, pancreatitis, hypoparathyroidism, and infertility or repeated miscarriages.

Most symptoms in WD first appear in the second and third decades of life; thus, the diagnosis is sometimes difficult and delayed. Most WD patients with hepatic encephalopathy and ALF would have already developed decompensated liver cirrhosis. Therefore, the disease is usually severe and may often be fatal without liver transplantation (LT).

The New Wilson Index Score (NWIS) is an important indication criterion for LT in cases of severe ALF in WD[2]. Although Dhawan et al[2] reported that patients with WD who present with ALF with an NWIS > 11 cannot survive without undergoing LT, we have previously demonstrated that even a WD patient with NWIS >11 could recover from ALF with treatment consisting of Zn, chelator and plasma exchange (PE)[3]. Here, we report a new case of WD with arthritic pain in the knee and liver cirrhosis. The patient developed ALF with NWIS >11 and stage I hepatic encephalopathy but survived with Zn and chelator treatment, without the need for continuous hemodiafiltration (CHDF) or PE. His arthritic pain was also alleviated with improved liver function; however, his knee pain deteriorated with increased blood alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels, and he could not walk by himself.

A 11-year-old boy complained of pain in both knees and sought an orthopedic consultation. The orthopedic surgeon did not detect any problem in his knees. He consulted his general physician for persistent pain in both knees. The physician noticed his pale complexion and edema of both the eyelids and lower limbs, and based on abdominal ultrasonography, diagnosed him with liver cirrhosis; he was subsequently referred to our institution.

The patient had experienced knee pain for 2 mo.

His neonatal history was unremarkable. He was born at 38 wk and 4 d of gestation with a birthweight of 2.66 kg and had no postnatal medical problems. He had been diagnosed with genu valgum several years prior.

The patient showed jaundice and splenohepatomegaly with tenderness in both hypochondrial regions. His vital signs were normal.

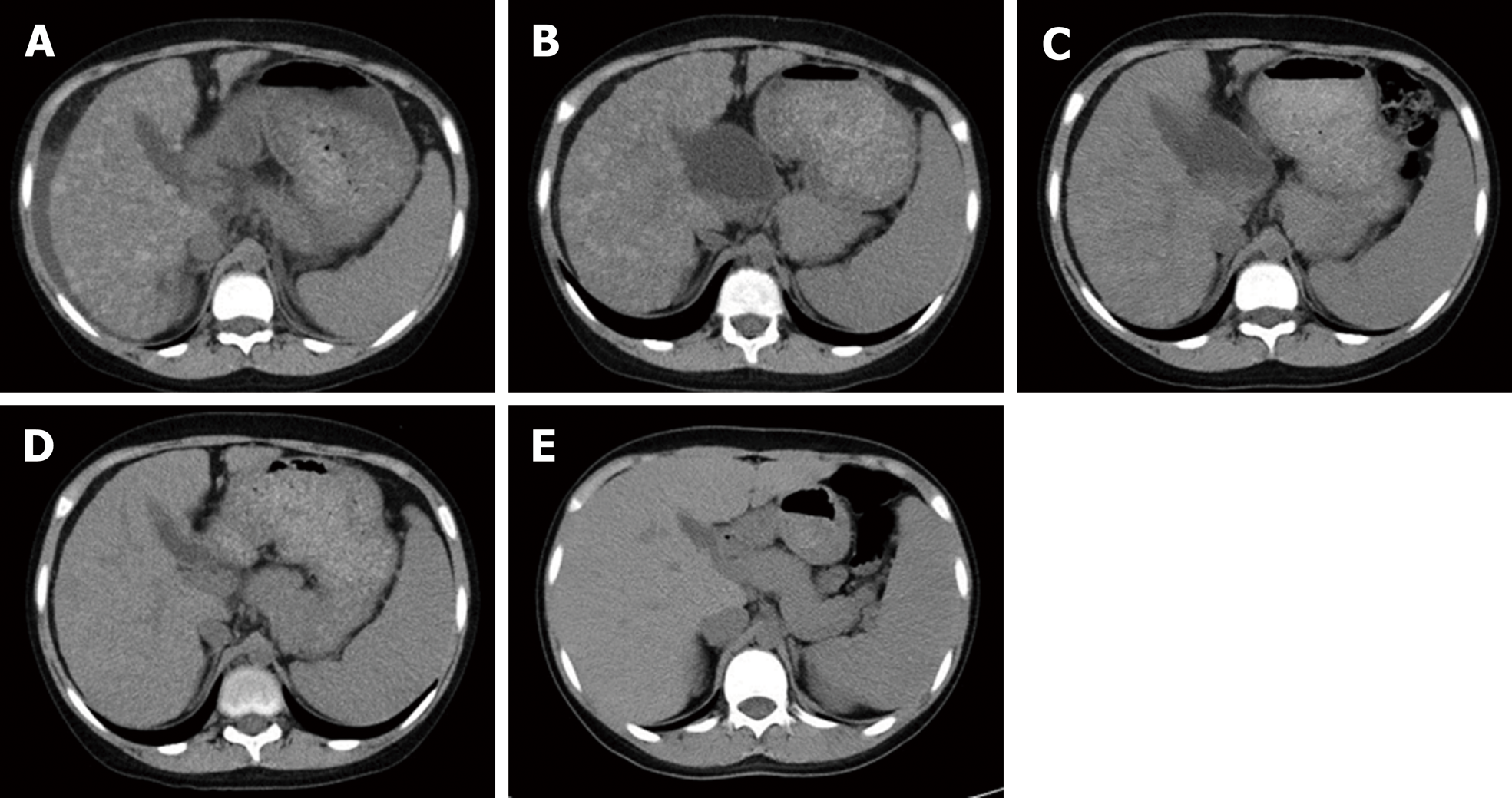

Laboratory data and abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed liver cirrhosis (Child-Pugh grade C) with ascites and liver atrophy. Multiple high-density mottled nodular shadows scattered in the liver were observed (Figure 1).

The diagnosis of WD was suspected due to his presentation with severe ALF (Table 1), and he immediately received treatment with Zn (3 mg/kg/d), concentrated human anti-thrombin III, and fresh-frozen plasma (FFP). His consciousness and physical lethargy gradually improved. The diagnosis of WD was confirmed based on low copper (27 mg/dL) and serum ceruloplasmin (7.0 mg/dL) levels, elevated urinary copper excretion (720 µg/d), and the presence of Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia [hemoglobin (Hb) level, 9.5 g/dL] without definite K-F rings. Moreover, gene analysis revealed compound heterozygous mutations (p.Arg778Leu/c.2333G>T and p.Asn958ThrfsX9/c.2871delC). The Leipzig’s score[4] for WD diagnosis was 9.

| Day 0 | Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 5 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 21 | Day 31 | Day 42 | Day 61 | Day 98 | Day 118 | Day 180 | Day 287 | Day 371 | Day 441 | |

| WBC (×103/μL) | 9.6 | 7.5 | 6.6 | 4.7 | 5 | 3.5 | 3.9 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 5.6 | 5.9 | 3.9 | 5.3 | 4.9 | 5.8 | 5.7 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 9.5 | 9.8 | 10.7 | 10.9 | 10.8 | 10.7 | 9.6 | 9.3 | 8.9 | 8.3 | 8.9 | 8.9 | 9.4 | 9.8 | 10.5 | 11.6 |

| Plt (103/μL) | 126 | 144 | 145 | 130 | 124 | 43 | 46 | 51 | 58 | 69 | 91 | 80 | 132 | 187 | 166 | 160 |

| PT (%) | 18 | 18 | 23 | 24 | 22 | 21 | 19 | 20 | 22 | 24 | 31 | 31 | 43 | 57 | 60 | 79 |

| PT-INR | 3.1 | 3 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| APTT (%) | 27 | 26 | 30 | 29 | 24 | 28 | 22 | 23 | 22 | 24 | 35 | 38 | 50 | 66 | 78 | 78 |

| ATIII (%) | NA | 20 | 22 | 45 | 46 | 51 | 53 | 33 | 25 | 26 | 35 | 32 | 64 | 90 | 115 | 136 |

| Factor V(%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 13 | 16 | 15 | 19 | 15 | 25 | 33 | 27 | 46 | 81 | 84 | 80 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 9.9 | 7 | 8.3 | 7.1 | 7.7 | 9.8 | 8.4 | 9.8 | 9.2 | 8.6 | 8 | 8.1 | 8.7 | 10.7 | 8.5 | 9.6 |

| Cr (mg/dL) | 0.49 | 0.5 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.36 |

| AST (IU/L) | 156 | 79 | 53 | 48 | 47 | 76 | 51 | 60 | 55 | 55 | 69 | 75 | 64 | 43 | 38 | 31 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 67 | 26 | 30 | 29 | 33 | 69 | 49 | 50 | 42 | 39 | 54 | 68 | 53 | 46 | 45 | 39 |

| LDH (IU/L) | 450 | 386 | 290 | 272 | 258 | 247 | 222 | 219 | 217 | 218 | 256 | 286 | 263 | 196 | 179 | 188 |

| T-Bil (mg/dL) | 4.9 | 2.6 | 2 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 2 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| D-Bil (mg/dL) | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| TP (g/dL) | 4.8 | 5.8 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 7 | 6.9 | 6.5 | 6.1 | 6.8 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 7.6 |

| ALB (g/dL) | 1.4 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 3.3 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.7 |

| 1PELD score | 26 | 22 | 14 | 12 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 14 | 8 | 8 | 2 | -4 | -5 | -9 |

| NWIS | 12 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| The Devarbhavi’s score | 8.11 | 5.65 | 2.14 | 1.82 | 1.50 | 1.93 | 2.14 | 2.57 | 3.42 | 3.10 | 1.39 | 1.18 | 0.54 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.32 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | I | I | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

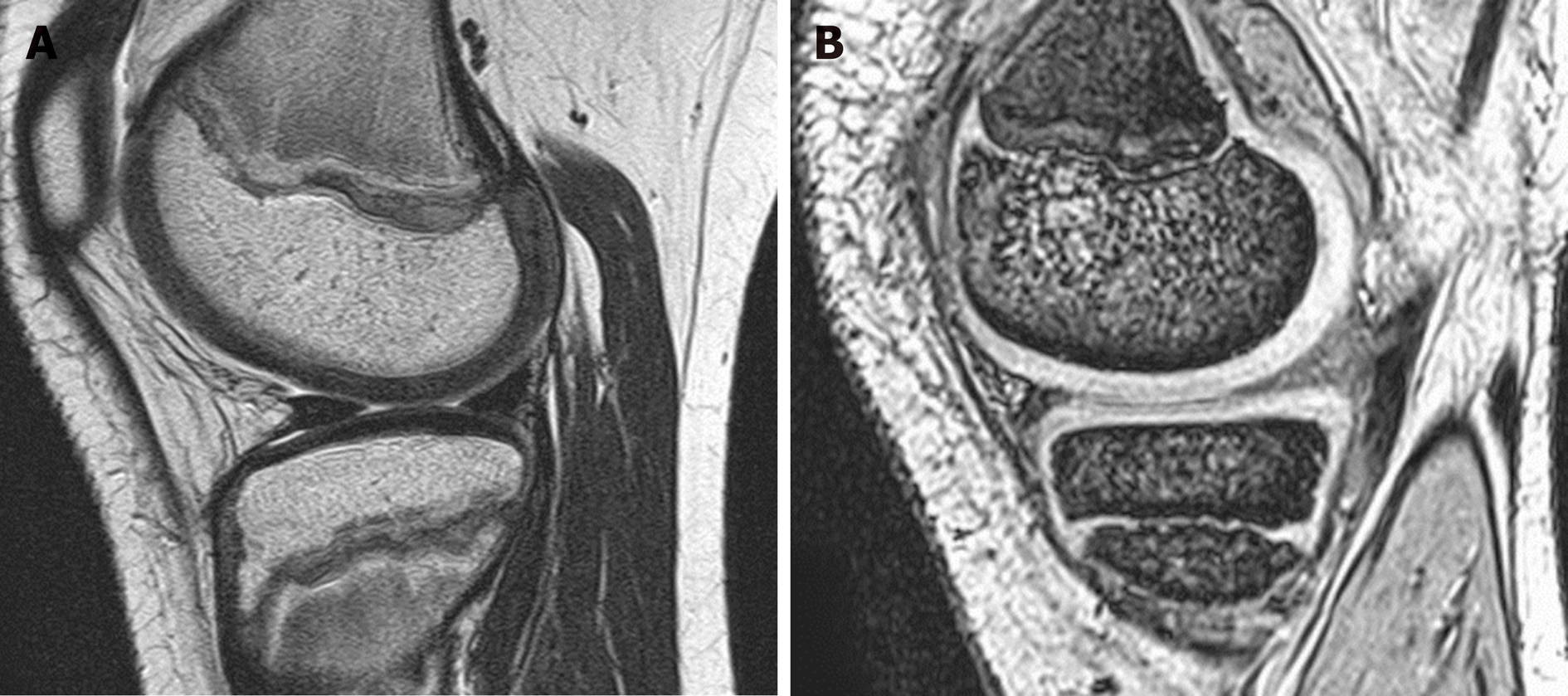

He received combination therapy with Zn and trientine following the diagnosis of WD, and his physical condition gradually improved. However, he complained of pain in both knees and had difficulty walking by himself. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the knee did not show significant abnormal findings (Figure 2).

The patient was discharged after prolonged hospitalization for 70 d because of the time required for the recovery of the coagulation parameters [prothrombin time (PT): 24%, prothrombin time-international normalized ratio (PT-INR): 2.5]. A liver CT scan performed 2 mo after hospitalization revealed fewer hyperdense mottled nodular shadows compared to those observed in the CT scans recorded at the time of hospitalization. Following his discharge, the coagulation parameters and liver CT findings became almost normal by one year after the initiation of therapy.

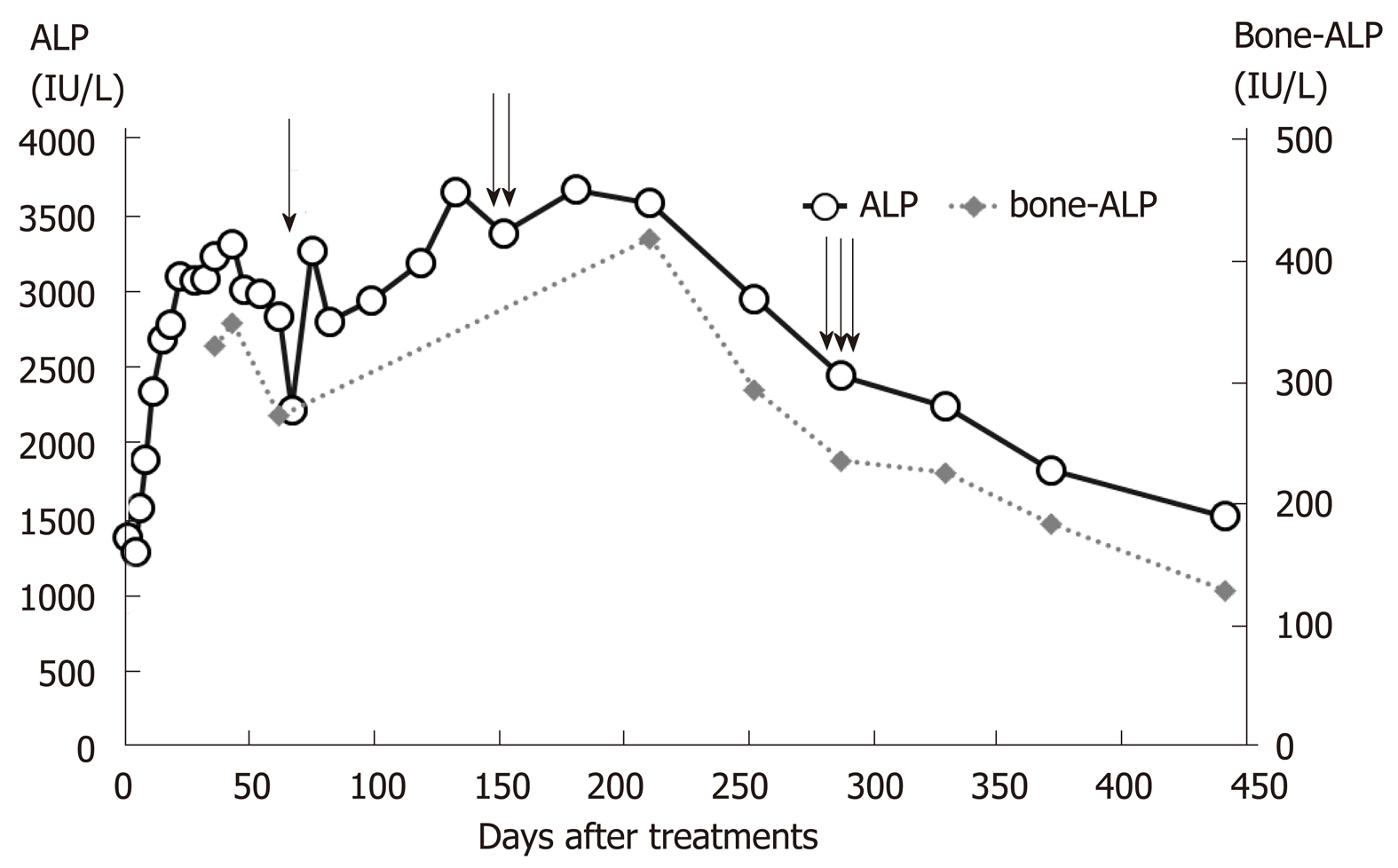

Although his knee pain was alleviated and blood ALP levels were decreased at the time of discharge, his knee pain persisted for some months after discharge and markedly improved with a further decrease in blood ALP levels (Figure 3), and he could walk by himself with little pain and could continue his schooling following treatment with Zn (1 mg/kg/d) and trientine (10 mg/kg/d). The coagulation parameters and liver CT findings also became almost normal by one year after the start of therapy.

Our patient with WD and severe ALF presented initially with arthritic pain in both knees. Here we report that a patient with ALF with WD could recover normal liver function by one year after initiation of combination therapy with Zn and trientine (Table 1). The mutations of p.Arg778Leu/c.2333G>T and p.Asn958ThrfsX9/c.2871delC present in this patient have been commonly detected in Japanese patients with WD[5]. Previously, WD patients presenting with ALF with an NWIS >11 were considered to require LT for successful treatment[2]. However, in recent years, certain institutions have reported that some WD patients developing severe ALF with an NWIS > 11, even when presenting with stage II hepatic encephalopathy, can be rescued following conservative therapy with Zn, chelators, CHDF and/or plasma exchange without LT[3,6-8]. We administered Zn to our patient immediately on suspecting WD based on his abdominal CT findings. Moreover, we monitored his clinical course, administering FFP and transfusing glucose and electrolytes without CHDF, as he had developed ALF with mild hyperbilirubinemia and significant coagulopathy without definite encephalopathy. CHDF was not performed because there was mild improvement in his physical condition without any deterioration of liver function and consciousness in the first 3 d following treatment with Zn and the aforementioned conservative therapies. A combination of Zn and trientine therapy was initiated after confirming the diagnosis of WD.

Santos et al[9] reported that even patients with decompensated WD could recover in one year following either chelator treatment alone or combination therapy with Zn and chelators, even though they qualified as candidates for LT. In our patient, the combination therapy of Zn and trientine for 14 months contributed to the recovery of the liver function and liver CT findings to almost normal levels. Therefore, teenagers with WD and decompensated liver cirrhosis are likely to recover normal liver functions following treatment with combination therapy involving Zn and trientine.

Devarbhavi et al[7] reported that children aged less than 18 years with WD who developed ALF leading to impaired consciousness were evaluated for LT, and that children with WD with hepatic encephalopathy and a Devarbhavi’s score ≥10.4 could not be rescued without LT. Devarbhavi’s score in our case was 8.1. The children with WD discussed in Devarbhavi et al[7] report had only stage I or II hepatic ence-phalopathy. Therefore, we considered that patients with decompensated WD, with mildly impaired consciousness, mildly elevated blood total bilirubin (T-Bil) levels, and an NWIS > 11, could be rescued without receiving LT.

Although MRI of the knee did not reveal significant abnormal findings, osteoarthritis has been reported as a rare complication of WD, and Golding et al[1] reported on the clinical and radiological features of arthropathy of WD. Nazer et al[10] reported some evidence of bony abnormality ranging from mild demineralization to chondromalacia and osteoarthritis. The cause of these bone abnormalities is not known and is not likely to be related to copper toxicity alone, because copper loading in experimental animals does not lead to bone abnormalities. Moreover, patients with severe hepatic WD who were diagnosed and treated in our hospital did not present with knee pain[3]. The knee pain in the present case deteriorated after the patient’s liver function improved.

Moreover, Golding et al[1] suggested that these bone changes in patients with WD resulted from the loss of calcium and phosphorus in the urine; therefore, the bone changes could be related to chelator therapy, also because of unusual bone mineral metabolism in the resorption and remodeling of the new bone during chelator therapy[1]. Our patient presented with knee pain before receiving treatment, and the knee pain deteriorated following trientine treatment; the pain improved after he had received trientine treatment for one year. The patient had genu valgum, which might have been a complication of longstanding WD. The blood ALP levels significantly increased on trientine treatment. The blood ALP levels correlated with the knee pain, and when the increased ALP level deceased to less than 2500 (IU/L) on Day 287, the patient experienced a definite improvement in knee pain and could walk by himself. It is not the increased blood ALP levels per se, but a ratio of ALP to T-Bil < 2.0 that is referred to in the diagnosis of severe WD. However, in cases of severe WD with bone symptoms, these referral values may not be relevant.

Even patients with WD who develop ALF with an NWIS >11 may be able to survive without LT if they present with mild hyperbilirubinemia and stage ≤ II hepatic encephalopathy. Moreover, the arthritic pain is not associated with the severity of WD. The pain temporarily deteriorates, but eventually improves following Zn and chelator therapy because bone mineral metabolism itself leads to a stable state.

We are grateful the patient’s primary doctor who introduced the patient to us and all staff members at the Department of Pediatrics and Department of Transplantation and Pediatric Surgery in Kumamoto University Hospital for their help in clinical practice.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ahmad TAA, Luo M S-Editor: Cui LJ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Golding DN, Walshe JM. Arthropathy of Wilson's disease. Study of clinical and radiological features in 32 patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 1977;36:99-111. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 77] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dhawan A, Taylor RM, Cheeseman P, De Silva P, Katsiyiannakis L, Mieli-Vergani G. Wilson's disease in children: 37-year experience and revised King's score for liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:441-448. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 296] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 228] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kido J, Matsumoto S, Momosaki K, Sakamoto R, Mitsubuchi H, Inomata Y, Endo F, Nakamura K. Plasma exchange and chelator therapy rescues acute liver failure in Wilson disease without liver transplantation. Hepatol Res. 2017;47:359-363. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ferenci P, Caca K, Loudianos G, Mieli-Vergani G, Tanner S, Sternlieb I, Schilsky M, Cox D, Berr F. Diagnosis and phenotypic classification of Wilson disease. Liver Int. 2003;23:139-142. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Tatsumi Y, Hattori A, Hayashi H, Ikoma J, Kaito M, Imoto M, Wakusawa S, Yano M, Hayashi K, Katano Y, Goto H, Okada T, Kaneko S. Current state of Wilson disease patients in central Japan. Intern Med. 2010;49:809-815. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Eisenbach C, Sieg O, Stremmel W, Encke J, Merle U. Diagnostic criteria for acute liver failure due to Wilson disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1711-1714. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 67] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 58] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Devarbhavi H, Singh R, Adarsh CK, Sheth K, Kiran R, Patil M. Factors that predict mortality in children with Wilson disease associated acute liver failure and comparison of Wilson disease specific prognostic indices. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:380-386. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tian Y, Gong GZ, Yang X, Peng F. Diagnosis and management of fulminant Wilson's disease: a single center's experience. World J Pediatr. 2016;12:209-214. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Santos Silva EE, Sarles J, Buts JP, Sokal EM. Successful medical treatment of severely decompensated Wilson disease. J Pediatr. 1996;128:285-287. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Nazer H, Ede RJ, Mowat AP, Williams R. Wilson's disease: clinical presentation and use of prognostic index. Gut. 1986;27:1377-1381. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 151] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |