Published online Sep 14, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i34.3908

Peer-review started: April 4, 2018

First decision: May 29, 2018

Revised: July 12, 2018

Accepted: July 22, 2018

Article in press: July 21, 2018

Published online: September 14, 2018

To determine the clinical characteristics of elderly patients of hemorrhagic gastroduodenal ulcer on low-dose aspirin (LDA) therapy.

A total of 1105 patients with hemorrhagic gastroduodenal ulcer treated in our hospital between January 2000 and March 2016 were grouped by age and drugs used, and these groups were compared in several factors. These groups were compared in terms of length of hospital stay, presence/absence of hemoglobin (Hb) decrease, presence/absence of blood transfusion, Forrest I, percentage of Helicobacter pylori infection, presence/absence of underlying disease, and percentage of severe cases.

The percentage of blood transfusion (62.6% vs 47.7 %, P < 0.001), Hb decrease (53.8% vs 40.8%, P < 0.001), and the length of hospital stay (23.5 d vs 16.7 d, P < 0.001) were significantly greater in those on drug therapy. The percentage of blood transfusion (65.3% vs 47.8%, P < 0.001), Hb decrease (54.2% vs 42.1%, P < 0.001), and length of hospital stay (23.3 d vs 17.5 d, P < 0.001) were significantly greater in the elderly. In comparison with the LDA monotherapy group, the percentage of severe cases was significantly higher in the LDA combination therapy group when elderly patients were concerned (16.1% vs 34.0%, P = 0.030). Meanwhile, among those on LDA monotherapy, there was no significant difference between elderly and non-elderly (16.1% vs 16.0%, P = 0.985).

A combination of LDA with antithrombotic drugs or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) contributes to aggravation. And advanced age is not an aggravating factor when LDA monotherapy is used.

Core tip: A total of 1105 patients with hemorrhagic gastroduodenal ulcer were grouped by age and drugs used, and these groups were compared in several factors. Among the elderly (over 70 years), the rate of severe conditions was significantly higher in patients receiving low-dose aspirin (LDA) combination therapy than in those receiving LDA monotherapy. Meanwhile, in the LDA monotherapy group, no significant difference in the rate of severe conditions was observed between elderly and non-elderly patients. This result suggests LDA combination therapy contributes to the aggravation, and advanced age is not an aggravating factor when LDA monotherapy is used.

- Citation: Fukushi K, Tominaga K, Nagashima K, Kanamori A, Izawa N, Kanazawa M, Sasai T, Hiraishi H. Gastroduodenal ulcer bleeding in elderly patients on low dose aspirin therapy. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(34): 3908-3918

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i34/3908.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i34.3908

Japan’s population is aging rapidly. According to the White Paper on Aging Society 2016, Cabinet office, Government of Japan, people 65 years of age or older accounted for 27.3% of the total population as of October 1, 2016. Under a situation where cerebrovascular disorder and ischemic heart disease have been increasing, clinical evidence of the usefulness of low-dose aspirin (LDA) as a means of secondary prevention of such diseases has often been reported and the frequency of its use has increased[1-3]. However, Pearson et al[4] reported that the use of LDA caused an approximately 20% decrease in cardiovascular events in comparison with the control group, but its use was associated with a 2.7-fold higher risk of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Serious adverse responses to LDA include gastrointestinal mucosal disorder and gastrointestinal hemorrhage; therefore, there is a concern for an increase and aggravation of these conditions[5-9].

Based on the Special Report of Vital Statistics in Japan issued by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, data in 1996, when the number of patients with gastric ulcer was the greatest after 1990, and the latest available data in 2014 were compared in regard to the number of patients with gastroduodenal ulcer and the number of deaths from gastroduodenal ulcer. The number of patients and the number of deaths in 1996 were 1124000 and 4514, respectively, whereas the corresponding numbers were 311000 (28% of the number in October 1996) and 2770 (61% of the number in 1996) in October in 2014. Although the number of patients with ulcer was decreased to less than one third, there was no marked decrease in the number of deaths from ulcer. This indicates that the clinical picture of ulcer became more severe, presumably reflecting an increase in the incidence of ulcer due to the increased use of antithrombotic drugs including LDA in the aging society, whereas the rate of infection with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) has decreased, and the rate of H. pylori eradication has increased, in the younger generation in recent years[10]. In particular, combined use of LDA and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and advanced age serve as risk factors for the occurrence of LDA-induced ulcer and also increase the risk of hemorrhage and aggravation[11-14]. According to a sub-analysis by Nikolsky et al[15], who investigated the presence/absence and prognosis of gastrointestinal hemorrhage within 30 d of hospitalization due to acute coronary syndrome, the overall mortality at 1 year was significantly higher in patients who had gastrointestinal hemorrhage within 30 d of hospitalization than in those who did not. In this study, we paid attention to patients who were on oral LDA therapy, a clinically important issue, among elderly patients with hemorrhagic gastroduodenal ulcer due to oral antithrombotic therapy to elucidate the clinical characteristics of this condition and analyzed patients with hemorrhagic gastroduodenal ulcer treated in our hospital in relation to age and medication.

This study included 1105 patients who had hematemesis, melena, or acute anemia symptoms due to hemorrhagic gastroduodenal ulcer [801 (72.5%) cases of gastric ulcer and 304 (27.5%) cases of duodenal ulcer] and who underwent emergency endoscopic hemostasis because upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage was suspected in Dokkyo Medical University Hospital between January 2000 and March 2016. These 1105 patients comprised inpatients, outpatients at the emergency department, and emergency transport patients.

The rules of our response to hemorrhagic gastric and duodenal ulcers are as follows: (1) hemostasis is rapidly and continuously performed by a gastroenterologist; (2) the hemostasis procedure uses clipping or argon plasma coagulation at the operator’s discretion, and a local injection of hypertonic saline epinephrine (HSE) and thrombin spray are employed if necessary without restriction to a single technique; (3) blood transfusion is indicated for patients with hemoglobin (Hb) ≤ 70 g/L or patients in shock; (4) intravenous administration of a proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is given promptly after endoscopic hemostasis, and it is switched to oral administration after initiation of oral feeding; (5) oral feeding is begun with thin rice gruel if blood test shows no progression of anemia and if no bleeding is found by second-look endoscopy performed within 0-5 d; and (6) when the patient is on antithrombin drug or anticoagulation drug therapy, discontinuation of the drug therapy is considered in consultation with a doctor of the specialty concerned after evaluating the risk of thrombosis, embolism, and bleeding.

Patients aged 70 years or older were defined as elderly, and those aged younger than 70 years were defined as non-elderly. A significant decrease in the Hb level was defined as a decrease of at least 20 g/L in comparison with the Hb level in the previous blood examination or as an Hb level of 70 g/L or lower in the absence of available data in the previous blood examination. As for H. pylori infection, it was possible that the urea breath test would provide a false-negative result because of the PPIs administered. Therefore, H. pylori-IgG antibody was measured in all subjects, and antibody titers of 10 U/mL or more were defined as positive. Multiple ulcer was defined by the presence of two or more ulcer lesions. Rebleeding was defined by the endoscopic evidence and additional treatment of hemorrhage within 72 h after the implementation of the initial endoscopic hemostasis. Hemorrhage found after more than 72 h was defined as recurrence. Severe cases were defined as cases with at least two of the following three items: (1) an Hb decrease of 20 g/L or more or blood transfusion; (2) hospital stay of at least 30 d; and (3) rebleeding, surgery, interventional radiology (IVR), or death. The oral drugs examined included antiplatelet drugs, such as LDA, thienopyridines (clopidogrel, ticlopidine, and prasugrel), and cilostazol, and anticoagulation drugs such as warfarin, heparin, and direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban). LDA, administered at doses of 70–330 mg/d, reportedly provides an antiplatelet effect[6,11]. In Japan, LDA is usually prescribed at a dose ≤ 162 mg/d. This also applies to the present study. In addition, the use of NSAIDs was also examined. The subjects were also examined for the presence/absence of cardiac disease, cerebrovascular disorder, renal disease, peptic ulcer, and diabetes mellitus as possible underlying diseases.

This was a retrospective study. The medical records of the subjects were examined for patient age, sex, Hb level, presence/absence of blood transfusion, Forrest classification, the number of ulcerative lesions, oral drugs, underlying disease, presence/absence of H. pylori infection, etc. These subjects were divided into those who were on oral drug therapy and those who were not and were also classified as elderly and non-elderly patients. These groups were compared in regard to the percentage of patients with blood transfusion, Hb decrease, rebleeding, surgery, IVR, or fatal outcome, and the length of hospital stay. In addition, among patients on oral drug therapy, attention was focused on LDA; in each of the LDA monotherapy group and LDA combination therapy group, the percentage of severe cases was analyzed in relation to elderly and non-elderly patients. To investigate factors for aggravation of the condition in elderly patients, the elderly group was further divided into those with and without severe conditions for comparison.

For statistical analysis, χ2 test, t test, and Mann-Whitney U test were used. Logistic regression analysis was also performed using hospital stay of 20 d or more as a dependent variable. SPSS version (IBM SPSS Statistics 21; IBM Japan, Ltd.) was used for statistical analysis processing. This study was approved by the life ethics committee of our institution.

The numbers (percentages) of patients with gastric ulcer and duodenal ulcer were 801 (72.5%) and 304 (27.5%), respectively. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients with gastroduodenal ulcer examined in this study. These patients were classified into those with oral drug therapy (medicated group) and those without oral drug therapy (non-medicated group). The medicated group comprised 474 (42.9%) patients, whereas the non-medicated group comprised 631 (57.1%) patients. These patients were also divided into elderly and non-elderly patients. There were 436 (39.5%) and 669 (60.5%) elderly and non-elderly patients, respectively. Table 2 shows the patient characteristics of each group.

| Items | All cases (n = 1105) |

| Mean age (yr) | 64.37 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 823 (74.5) |

| Female | 282 (25.5) |

| Mean length of hospital stay (d) | |

| After endoscopic treatment | 19.8 |

| Overall | 22.1 |

| Hb (mg/L) | 87.4 |

| Hb decrease | 509 (46.1) |

| Blood transfusion | 594 (53.8) |

| H. pylori positive | 857 (77.6) |

| Endoscopic findings | |

| Ulcer | |

| Single | 759 (68.7) |

| Multiple | 346 (31.3) |

| Forrest classification | |

| Ia | 88 (8.0) |

| Ib | 171 (15.5) |

| IIa | 525 (47.5) |

| IIb | 142 (12.8) |

| III | 179 (16.2) |

| Rebleeding | 82 (7.4) |

| Recurrence | 60 (5.4) |

| Surgery/IVR/death | 32 (2.9) |

| Prophylactic anti-ulcer medication | |

| None | 749 (67.8) |

| PPI | 88 (8.0) |

| H2RA | 117 (10.6) |

| MP | 152 (13.6) |

| Comorbidity | |

| Cardiac disease | 254 (30.0) |

| Cerebrovascular disorder | 180 (16.3) |

| Renal failure | 125 (11.3) |

| DM | 198 (17.9) |

| Orthopedic disorder | 162 (14.7) |

| History of ulcer | 317 (28.7) |

| Medicated group (n = 474) | Non-medicated group (n = 631) | P value | Elderly group (n = 436) | Non-elderly group (n = 669) | P value | |

| Mean age (yr) | 69.7 | 60.4 | < 0.001 | 78.5 | 54.9 | < 0.001 |

| Sex (male:female) | 352:122 | 491:140 | < 0.001 | 271:165 | 552:117 | < 0.001 |

| Hb (mg/L) | 82.6 | 91.1 | < 0.001 | 80.8 | 91.9 | < 0.001 |

| H. pylori infection (positive:negative) | 73.5% (324:117) | 89.3% (533:64) | < 0.001 | 77.9% (311:88) | 85.4% (546:93) | 0.002 |

| Single ulcer | 61.4% (291:183) | 74.2 (468:163) | < 0.001 | 40.1% (175:261) | 25.6% (171:498) | < 0.001 |

| ForrestI | 25.7% (122:352) | 21.7% (137:494) | 0.118 | 25.5% (11:325) | 22.1% (148:521) | 0.201 |

| Anti-ulcer medication | 52.1% (247:227) | 17.3% (109:522) | < 0.001 | 41.3% (189:256) | 26.3% (176:493) | < 0.001 |

| Underlying disease | ||||||

| Cardiac disease | 43.0% (204:270) | 7.9% (50:581) | < 0.001 | 33.9% (148:288) | 15.8% (106:563) | < 0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disorder | 25.9% (123:351) | 4.0% (25:606) | < 0.001 | 22.2% (97:339) | 7.6% (51:618) | < 0.001 |

| Renal disease | 16.5% (78:396) | 7.4% (47:584) | < 0.001 | 13.1% (57:379) | 10.2% (68:601) | 0.136 |

| Respiratory disease | 13.5% (64:410) | 8.1% (51:580) | 0.003 | 14.9% (65:371) | 7.5% (50:619) | < 0.001 |

| Orthopedic disorder | 28.9% (137:337) | 4.0% (25:606) | < 0.001 | 21.6% (94:342) | 10.2% (68:601) | < 0.001 |

| History of ulcer | 21.9% (104:370) | 28.7% (181:450) | < 0.001 | 18.3% (80:356) | 30.6% (205:464) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 41.4% (196:278) | 25.9% (158:473) | < 0.001 | 45.2% (197:239) | 23.5% (157:512) | < 0.001 |

| DM | 21.7% (103:371) | 15.1% (95:536) | 0.004 | 18.3% (80:356) | 17.6% (118:551) | 0.763 |

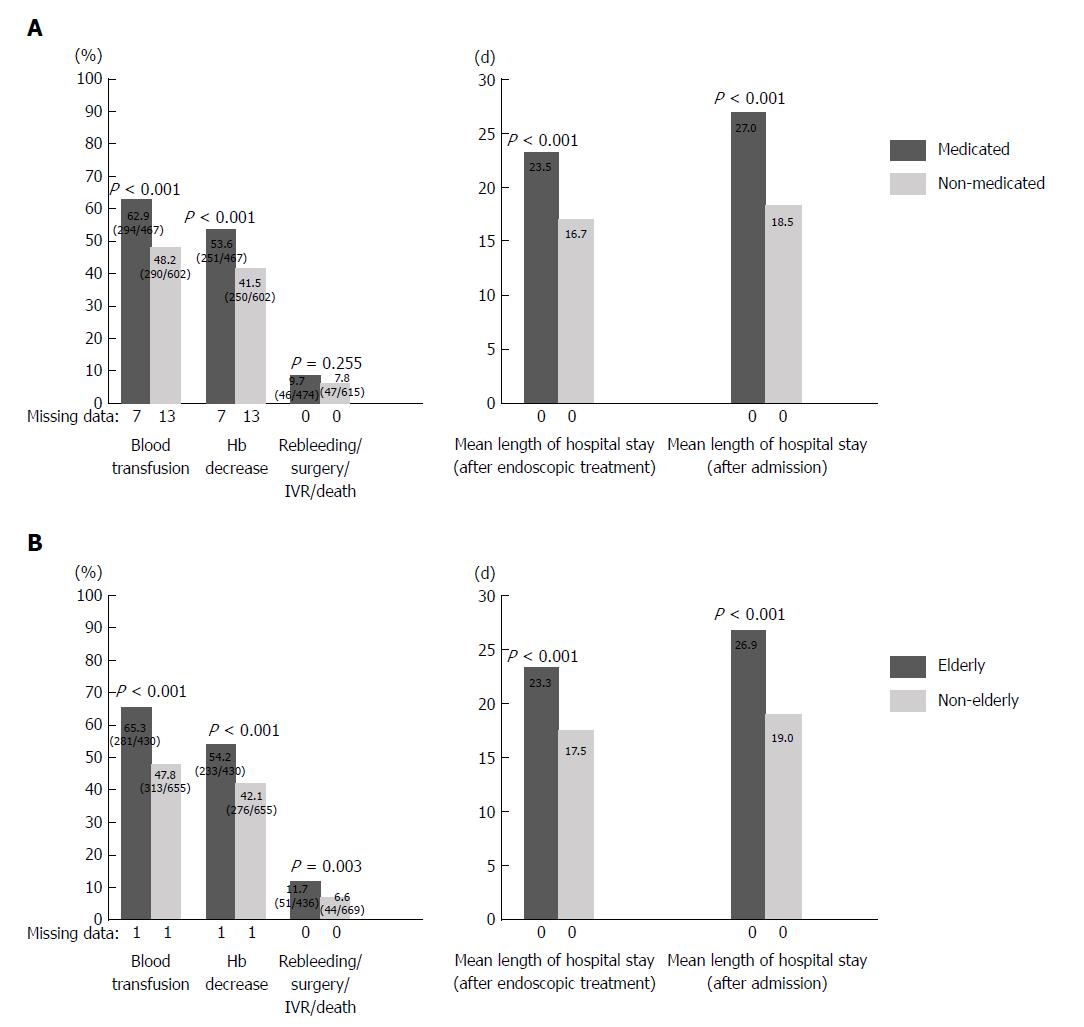

Types of oral medication included 474 patients (113 cases of LDA monotherapy and 157 cases of NSAIDs monotherapy and 113 cases of clopidogrel monotherapy and 10 cases of cilostazol monotherapy and 40 cases of warfarin monotherapy and 4 cases of DOACs monotherapy, and 118 cases of combination therapy). When the medicated and non-medicated groups were compared, the percentage of patients with blood transfusion (62.6% vs 47.7%; P < 0.001) and the percentage of patients with Hb decrease (53.8% vs 40.8%; P < 0.001) were significantly higher in the medicated group (Figure 1A). The length of hospital stay after the implementation of endoscopic treatment (23.5 d vs 16.7 d; P < 0.001) and the overall length of hospital stay (27.0 d vs 18.5 d; P < 0.001) were significantly longer in the medicated group. There was no significant difference with regard to rebleeding, surgery, IVR, or mortality between the two groups.

| Elderly patients (n = 111) | Non-elderly patients (n = 99) | P (A vs B) | P (A vs C) | |||

| Group A: LDA monotherapy (n = 63) | Group B: LDA combination therapy (n = 48) | Group C: LDA monotherapy (n = 49) | Group D: LDA combination therapy (n = 50) | |||

| Mean age (yr) | 80.0 | 80.0 | 58.3 | 60.7 | 0.989 | < 0.001 |

| Sex (male:female) | 43:20:00 | 34:14:00 | 45:04:00 | 44:06:00 | 0.770 | 0.003 |

| Mean length of hospital stay (d) | ||||||

| After endoscopic treatment | 20.0 | 25.5 | 20.9 | 21.9 | 0.194 | 0.323 |

| Overall | 20.1 | 28.4 | 23.0 | 27.3 | 0.120 | 0.685 |

| Hb (mg/L) | 84.0 | 84.0 | 89.0 | 86.0 | 0.948 | 0.307 |

| Hb decrease (present:absent) | 43.5% (27:35) | 53.2% (25:22) | 49.0% (24:25) | 67.4% (31:15) | 0.702 | 0.569 |

| Blood transfusion (present:absent) | 61.3% (38:24) | 66.0% (31:16) | 38.8% (19:30) | 58.7% (27:19) | 0.690 | 0.018 |

| H. pylori infection (positive:negative) | 77.4% (48:14) | 68.3% (28:13) | 80.9% (38:9) | 68.8% (33:15) | 0.303 | 0.664 |

| Forrest (I:II, III) | 23.8% (15:48) | 27.1% (13:35) | 16.3% (8:41) | 20.0% (10:40) | 0.694 | 0.331 |

| Ulcer (multiple:single) | 42.9% (27:36) | 39.6% (19:29) | 22.4% (11:38) | 46.0% (23:27) | 0.846 | 0.024 |

| Rebleeding (present:absent) | 3.2% (2:61) | 12.5% (6:42) | 2.0% (1:48) | 8.0% (4:46) | 0.060 | 1.000 |

| Rebleeding/surgery/IVR/death (present:absent) | 3.2% (2:61) | 14.6% (7:41) | 4.1% (2:47) | 8.0% (4:46) | 0.038 | 1.000 |

| Recurrence (present:absent) | 0% (0:63) | 4.2% (2:46) | 8.2% (4:45) | 4.0% (2:48) | 0.185 | 0.034 |

| DM | 17.5% (11:51) | 25.0% (12:36) | 36.7% (18:31) | 36.0% (18:32) | 0.332 | 0.021 |

| Cardiac disease | 52.4% (33:30) | 66.7% (32:16) | 46.9% (23:26) | 78.0% (39:11) | 0.130 | 0.568 |

| Cerebrovascular disorder | 38.1% (24:39) | 39.6% (19:29) | 22.4% (11:38) | 34.0% (17:33) | 0.873 | 0.076 |

| Orthopedic disorder | 12.7% (8:55) | 25.0% (12:36) | 6.1% (3:46) | 20.0% (10:40) | 0.095 | 0.342 |

| Respiratory disease | 17.5% (11:52) | 14.6% (7:41) | 4.1% (2:47) | 4.0% (2:48) | 0.684 | 0.028 |

| Renal disease | 12.7% (8:55) | 22.9% (11:37) | 18.4% (9:40) | 24.0% (12:38) | 0.157 | 0.407 |

| History of peptic ulcer | 19.0% (12:51) | 12.5% (6:42) | 28.6% (14:35) | 20.0% (10:40) | 0.354 | 0.236 |

| Hypertension | 49.2% (31:32) | 52.1% (25:23) | 36.7% (18:31) | 42.0% (21:29) | 0.764 | 0.187 |

| Preceding anti-ulcer medication (present:absent) | 38.1% (24:39) | 79.2% (38:10) | 44.9% (22:27) | 58.0% (29:21) | < 0.001 | 0.468 |

| Preceding PPI medication | 11.1% (7:56) | 22.9% (11:37) | 12.2% (6:43) | 16.0% (8:42) | 0.095 | 0.853 |

The results of the comparison between elderly and non-elderly patients are shown in Figure 1B. The percentage of patients with blood transfusion (65.3% vs 47.8%; P < 0.001), percentage of patients with Hb decrease (54.2% vs 42.1%; P < 0.001), and percentage of patients with rebleeding, surgery, IVR, or death (11.7% vs 6.6%; P = 0.033) were significantly higher among elderly patients. The length of hospital stay after the implementation of endoscopic treatment (23.3 d vs 17.5 d; P < 0.001) and the overall length of hospital stay (26.9 d vs 19.0 d; P < 0.001) were significantly longer among elderly patients.

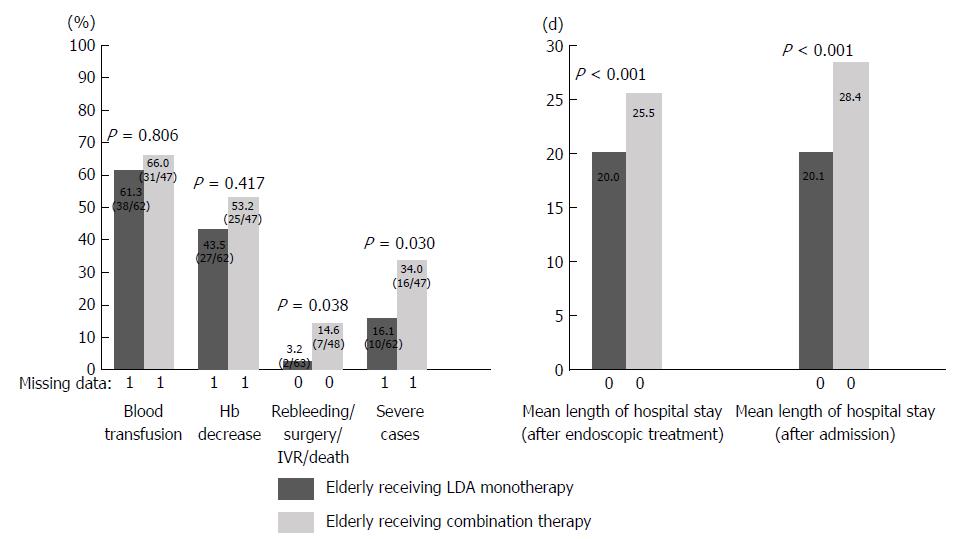

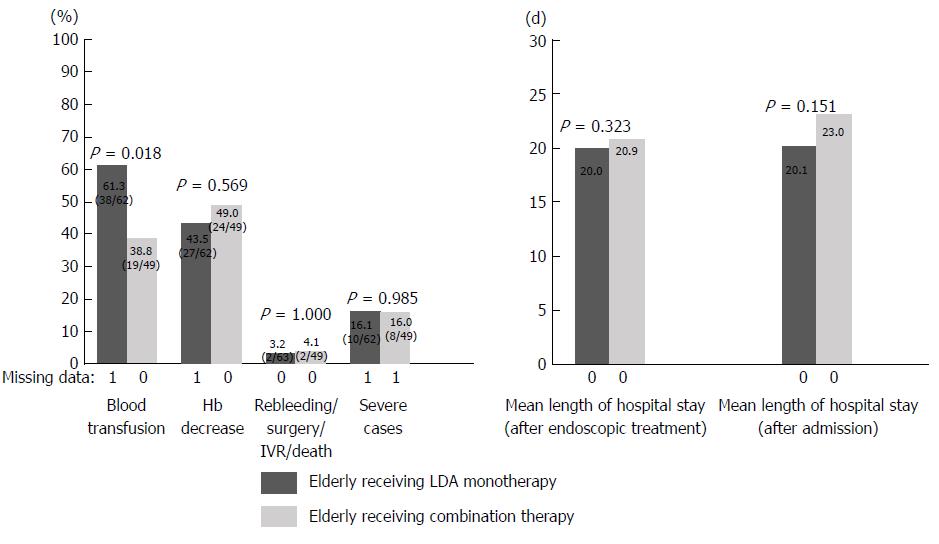

Patients in the medicated group were divided into those with LDA monotherapy or LDA combination therapy and elderly or non-elderly patients, and the percentage of severe cases and the length of hospital stay were examined. Patients in the medicated group were divided into groups A (elderly receiving LDA monotherapy), B (elderly receiving LDA combination therapy), C (non-elderly receiving LDA monotherapy), and D (non-elderly receiving LDA combination therapy). Elderly patients, a population that may have clinical issues, were investigated by comparing groups A and B. In addition, the age-related tendency in the LDA monotherapy group was examined by comparing groups A and C (Table 3). The results are shown in Figures 2 and 3. A comparison between groups A and B revealed that the length of hospital stay tended to be longer in group B than in group A (group A 20.0 d vs group B 25.5 d; P = 0.194). Rebleeding, surgery, IVR, and death were more frequent in group B than in group A (group A 3.2% vs group B 14.6%; P = 0.038). In comparison with group A, the percentage of severe cases was significantly higher in group B (group A 16.1% vs group B 34.0%; P = 0.030). A comparison of groups A and C showed no significant difference in the length of hospital stay or the percentage of severe cases between the two groups.

In the elderly group, severe cases defined by rebleeding or fatal outcome were compared with non-severe cases ending in discharge in remission to determine risk factors for aggravation (Table 4). There was a significant intergroup difference in regard to Hb decrease (70.0% vs 52.1%; P = 0.017), blood transfusion (88.0% vs 62.4%; P < 0.001), Forrest I (45.1% vs 22.9%; P = 0.001), HSE use (9.6% vs 21.6%; P = 0.010), and diabetes mellitus (29.4% vs 16.9%; P = 0.030). Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed blood transfusion [odds ratio (95%CI): 3.59 (1.42-9.06); P = 0.007], Forrest I [odds ratio (95%CI): 2.40 (1.07-4.54); P = 0.007], and diabetes mellitus [odds ratio (95%CI): 2.02 (1.00-4.06); P = 0.049] as independent risk factors.

| Elderly group (n = 436) | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

| Severe cases (n = 51) | Non-severe cases (n = 385) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Mean age (yr) | 79.0 | 78.8 | 0.846 | ||

| Sex (male:female) | 64.7% (33:18) | 61.8% (238:147) | 0.689 | ||

| Mean length of hospital stay (d) | |||||

| After endoscopic treatment | 21.9 | 23.5 | 0.699 | ||

| Overall | 25.9 | 27.0 | 0.823 | ||

| Hb (mg/L) | 76.3 | 81.4 | 0.113 | ||

| Hb decrease (present:absent) | 70.0% (35:15) | 52.1% (198:182) | 0.017 | 1.378 (0.693-2.74) | 0.361 |

| Blood transfusion (present:absent) | 88.0% (44:6) | 62.4% (237:143) | < 0.001 | 3.592 (1.423-9.064) | 0.007 |

| H. pylori infection (positive:negative) | 69.8% (30:13) | 78.9% (281:75) | 0.171 | ||

| Forrest (I:II, III) | 45.1% (23:28) | 22.9% (88:297) | 0.001 | 2.395 (1.065-4.537) | 0.007 |

| Ulcer (multiple:single) | 31.4% (16:35) | 41.3% (159:226) | 0.174 | ||

| HSE use | 21.6% (11:40) | 9.6% (37:348) | 0.010 | 2.178 (0.975-4.862) | 0.058 |

| DM | 29.4% (15:36) | 16.9% (65:320) | 0.030 | 2.018 (1.002-4.063) | 0.049 |

| Cardiac disease | 29.4% (15:36) | 34.5% (133:252) | 0.467 | ||

| Cerebrovascular disorder | 27.5% (14:37) | 21.6% (83:302) | 0.342 | ||

| Orthopedic disorder | 23.5% (12:39) | 21.3% (82:303) | 0.716 | ||

| Respiratory disease | 21.6% (11:40) | 14.0% (54:331) | 0.155 | ||

| Renal disease | 5.9% (3:48) | 14.0% (54:331) | 0.105 | ||

| History of peptic ulcer | 23.5% (12:39) | 17.7% (68:317) | 0.309 | ||

| Hypertension | 41.2% (21:30) | 45.7% (176:209) | 0.541 | ||

| Preceding anti-ulcer medication | 52.9% (27:24) | 39.7% (153:232) | 0.072 | ||

| Preceding PPI medication | 11.8% (6:45) | 11.7% (45:340) | 0.987 | ||

Aspirin exerts an anti-inflammatory action by inhibiting the activity of COX-1 and COX-2 as well as an antiplatelet action by inhibiting intraplatelet COX-1 and suppressing the production of thromboxane A2, a promoter of platelet aggregation. It is known that aspirin inhibits gastric mucosal protection through COX inhibition. In addition, aspirin takes a lipid-soluble nonionic form under the intragastric acidic condition and accumulates in the cell to cause injury directly, with increased drug permeability. Case-control studies conducted in Europe and North America showed that gastrointestinal mucosal disorder would increase the risk of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage about 2- to 4-fold[16-17]. Sakamoto et al[18] reported based on the results of a case-control study in Japanese people that the odds ratio of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage due to LDA was 8.2 (95%CI: 3.3-20.7). In addition, studies that examined the prognosis in relation to the presence or absence of the increasingly prevalent gastrointestinal hemorrhage after acute coronary syndrome or acute stroke found that the occurrence of gastrointestinal hemorrhage after acute coronary syndrome or acute stroke would increase the overall mortality at 1 year[15,19]. This should not only alert endoscopists but also alert cardiologists and neurologists. Antiplatelet drugs other than LDA are also associated with the risk of gastrointestinal hemorrhage because they inhibit thrombogenesis, but they cause less injury to the mucosa. Clopidogrel is known to increase the risk of hemorrhage by 1.7-2.8 times; case-control studies with more than 10000 cases showed that its risk of inducing hemorrhage is not statistically significant[16,17,20,21]. Because reports on antiplatelet drugs other than LDA are limited, accumulation of data and additional investigations in the future are awaited. The anticoagulant warfarin significantly increases the risk of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage by about two to four times[16,20-22]. In recent years, the use of DOACs as a new treatment of venous thromboembolism and atrial fibrillation has increased. In a cohort study, Shimomura et al[23] performed a long-term follow-up of 508 patients on oral anticoagulant therapy in whom peptic ulcer and hemorrhage were denied and calculated the incidence rate of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. As a result, acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage occurred in 8.3% of the patients during an average observation period of 31 mo, and the cumulative incidence rates of gastrointestinal hemorrhage at 5 and 10 years were reported to be 13% and 19%, respectively, which were clinically relevant. There was no significant difference in the hemorrhage risk between warfarin and DOACs. In addition, other more recent studies have found no significant difference in the hemorrhage risk between warfarin and DOACs[24,25]. Our present study included only four patients on DOACs therapy, and therefore DOACs were not analyzed. Because the use of DOACs is expected to increase in the future, additional investigations would be necessary.

Hallas et al[16] reported that the risk of hemorrhage was increased 1.8-fold by LDA monotherapy, and the risk was further increased by the combined use of LDA with other drugs, e.g., 7.4-fold by combination with clopidogrel and 5.3-fold by combination with warfarin. Several studies have demonstrated bleeding risk in patients treated with a combination of LDA plus antithrombotic drugs[26,27]. The present study showed that the condition was significantly more severe in elderly patients aged 70 years or older on LDA combination therapy than in those on LDA monotherapy. Although a comparison among different drugs was not made, this study indicated that the combined use of drugs would increase the risk of hemorrhage, requiring due caution. In addition, when LDA monotherapy was used, there was no significant difference in the severity of the condition between elderly and non-elderly patients. Although oral LDA therapy poses a risk of ulceration as mentioned previously, the results of this study suggest that LDA monotherapy does not contribute to aggravation of hemorrhage in elderly patients in comparison with non-elderly patients.

Increases in the incidence of rebleeding and mortality in relation to the underlying disease and age have been reported. Rockall et al[28] have reported that the fatality rate due to upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage was 14% (584/4412) and that the rate increased with the presence of comorbidities such as heart failure, ischemic heart disease, and renal failure. It has also been reported that the mortality within 30 d is proportional to the prevalence of serious comorbidities[29]. In addition, some researchers reported that the Glasgow Blatchford score was the most effective predictive factor for treatment intervention and death[30,31]. Travis et al[32] investigated the risk factors for rebleeding after endoscopy and reported that non-use of PPIs, hepatic cirrhosis, heparin, and the use of epinephrine were independent factors. In this study, the condition was more likely to be more severe in elderly patients and medicated patients, indicating that aggressive treatment intervention would be necessary in such patients. In addition, when elderly patients aged 70 years or older were concerned, Hb decrease, implementation of blood transfusion, Forrest I, HSE, and a history of diabetes mellitus were found to be risk factors for a severe clinical course (rebleeding, surgery, IVR or other treatment intervention, or death). When multivariate analysis was performed, Hb decrease, implementation of blood transfusion, and a history of diabetes mellitus were identified as independent factors. In these patients, endoscopically and clinically more appropriate management including an adequate endoscopic hemostatic procedure and an aggressive second-look procedure is required.

As for management after hemostasis, both the rebleeding risk due to continued oral antithrombotic medication and the risk of developing thromboembolism due to discontinuation of antithrombotic therapy should be considered. Thus, the method of such management is a clinically relevant issue. Discontinuation of antithrombotic drugs was previously reported to be associated with a significantly higher incidence of thromboembolic events and related deaths[5,16,33-35]. The risk of recurrence of underlying disease associated with discontinuation of LDA has also been reported to be significantly higher than the risk of recurrence of hemorrhagic gastric ulcer associated with continuation of LDA therapy[36]. Nagata et al[37] have reported that a history of thromboembolism, comorbidity score, discontinuation of LDA, discontinuation of antiplatelet drugs other than aspirin, and discontinuation of anticoagulant drugs were identified as risk factors for thromboembolism and that discontinuation of LDA and anticoagulant drugs resulted in a higher risk of thromboembolism. Therefore, when treating patients, it is necessary to consider the propriety of discontinuation of medication and avoid prolonged withdrawal, in consultation with specialists such as a cardiologist or a neurologist. Elderly patients are at a high risk of rebleeding and are more likely to discontinue antithrombotic medication. In such cases, a second-look procedure should be performed aggressively, and antithrombotic medication should be resumed as soon as possible. It is also necessary to ensure that antithrombotic medication is resumed on discharge.

With regard to LDA-induced peptic ulcer, several randomized controlled trails demonstrated the secondary preventive effect of PPIs, and in Japan, an additional indication for the use of PPIs to prevent recurrence of LDA-induced ulcer was approved for the first time in 2010[38-40]. In a randomized controlled trial that included patients aged 60 years or older who had no endoscopic evidence of ulcer, esomeprazole 20 mg proved to be effective for prevention of peptic ulcer (primary prevention)[41]. As mentioned previously, the incidence rates of severe ulcer and drug-induced ulcer are increasing, and administration of more appropriate acid-blocking drugs including PPIs has become important. Japanese guidelines recommend the use of PPIs[42]. However, as demonstrated in the present study, the actual frequency of the use of PPIs is currently low, and therefore further spread of this type of drugs is necessary.

Our present study had several limitations. This was a single-center retrospective study that provided restrictive analysis. Endoscopic skills varied among different endoscopists. The definition of severe ulcer was not based on any well-known scoring system but used unique factors produced from evaluable items. The age difference between elderly and non-elderly subjects was small 54.9 years vs 78.5 years. Addition of data and another verification with participation of multiple centers are desirable.

In conclusion, when patients on LDA combination therapy and LDA monotherapy were compared, the percentage of severe cases was high in those on LDA combination therapy among elderly patients, indicating that combined use of LDA with antithrombotic drugs or NSAIDs contributes to the aggravation of hemorrhagic gastroduodenal ulcer. In the LDA monotherapy group, there was no significant difference in the percentage of severe cases between elderly and non-elderly patients, indicating that age is not a risk factor for aggravation of the condition when LDA monotherapy is used.

As the Japanese population ages, the prevalence of cerebrovascular disorders and ischemic heart diseases have been increasing. Under these circumstances, low-dose aspirin (LDA) has increasingly been used for secondary prevention of such conditions in recent years. Severe adverse reactions to LDA include hemorrhagic gastroduodenal ulcer. In the future, the incidences of LDA-induced peptic ulcer and ulcer hemorrhage are expected to rise in the elderly.

As previously reported, the concomitant use of LDA and other antithrombotic drugs increases the risk of ulcer hemorrhage. However, no report of any study that LDA-induced ulcer hemorrhage in elderly patients who expected to become severe. Elucidation of the current status of this condition would thus be useful.

Of patients with hemorrhagic gastroduodenal ulcer caused by oral administration of antithrombotic drugs, those receiving oral LDA, which is likely to be particularly problematic, were targeted. By comparing elderly and non-elderly patients, this study aimed to identify clinical features of the ulcer and factors contributing to its progression to severe conditions. These issues are particularly important in countries that have become aged societies, like Japan, or are aging at a rapid rate.

This study included 1105 patients with hemorrhagic gastroduodenal ulcer, who were divided according age (the elderly group consisting of those 70 years of age or older and the non-elderly group consisting of those less than 70 years of age) and orally administered drugs (the LDA monotherapy group and the LDA combination therapy group). We retrospectively compared and analyzed the length of hospital stay, presence or absence of decreased hemoglobin (Hb) level, use of blood transfusion, rate of severe conditions, etc.

When elderly patients were compared between the LDA monotherapy and LDA combination therapy groups, the rate of severe conditions was higher in the LDA combination therapy group. Concomitant use of LDA with antithrombotic drugs or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs was found to contribute to the progression of severe hemorrhagic gastroduodenal ulcer to severe conditions. Moreover, among the LDA monotherapy group, no significant difference in the rate of severe conditions was observed between elderly and non-elderly patients. Oral administration of LDA alone was not found to be a risk factor for progression to severe conditions in elderly patients.

This study showed that LDA combination therapy contributes to progression to severe conditions, such as markedly decreased Hb levels, increased frequency of blood transfusion, and prolonged hospital stay, in elderly patients. Meanwhile, in cases receiving LDA monotherapy, advanced age is not a risk factor for progression to severe conditions. Based on these findings, when LDA combination therapy is administered to elderly patients, efforts should be made toward adequate prevention of hemorrhage. In cases with ulcer hemorrhage, while treatment is given, appropriate antithrombotic therapy is required to prevent the occurrence of vascular events. Furthermore, apparently, if LDA monotherapy is administered, even elderly patients may be at a risk of progression to severe conditions similar to that in non-elderly patients.

The limitations of this study include the single-center retrospective design. In addition, because the analysis in the LDA combination therapy group was not stratified according to the types of antithrombotic drugs used in combination with LDA, the effects of different combinations of drugs on the risk of hemorrhage should be examined in future studies. Although the use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is preferable for prevention of hemorrhage as described in the guidelines, further accumulation of additional data and studies on effects, adverse events, etc. are needed to use PPIs appropriately. Furthermore, evidence must be accumulated for the prophylactic effect of novel therapeutic drugs, such as vonoprazan, for ulcers in elderly patients.

The authors appreciate the great support with the statistical analyses provided by Yasuo Haruyama, Department of Public Health, Dokkyo Medical University. The authors also would like to thank all participants and staff members investigators who participated in this study: Yasunaga Suzuki, Yoshihito Watanabe, Kazunari Kanke, Takeshi Oinuma, Yukio Otsuka, Katsuo Morita, Takahiro Mitsuhashi, Michiko Matsuoka, Ayako Aoki, Jun Ishikawa, Etsuko Yonekura, Koji Sudo, Youichiro Fujii, Yutaka Okamoto, Daisuke Arai, Masaya Terauchi, Hayato Takagi, Kenji Yoshida, Takero Koike, Kenichiro Mukawa, Mina Hoshino, Takafumi Hoshino, Rieko Fujii, Genyo Hitomi, Naoto Yoshitake, Yasuyuki Saifuku, Mitsunori Maeda , Makoto Matsumaru, Kohei Tsuchida, Takeshi Sugaya, Masakazu Nakano, Chieko Tsuchida, Yoshimitsu Yamamoto, Kyoko Yamamoto, Misako Tsunemi, Hiroko Sakurai, Naoya Inaba, Takashi Akima, Hitoshi Kino, Yoshihito Kaneko, Atsushi Hoshino, Hidehito Jinnai, Toshinori Komatsubara, Shinji Muraoka, Fumiaki Takahashi, Tsunehiro Suzuki, Mari Iwasaki, Kazuhiro Takenaka, Keiichiro Abe, and Takahito Minaguchi.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor):

P- Reviewer: Caboclo JF, Rodrigo L, Tarnawski AS S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Yin SY

| 1. | Antithrombotic Trialists' Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324:71-86. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4959] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4468] [Article Influence: 203.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Weisman SM, Graham DY. Evaluation of the benefits and risks of low-dose aspirin in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2197-2202. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 195] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Eidelman RS, Hebert PR, Weisman SM, Hennekens CH. An update on aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2006-2010. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 183] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pearson TA, Blair SN, Daniels SR, Eckel RH, Fair JM, Fortmann SP, Franklin BA, Goldstein LB, Greenland P, Grundy SM. AHA Guidelines for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke: 2002 Update: Consensus Panel Guide to Comprehensive Risk Reduction for Adult Patients Without Coronary or Other Atherosclerotic Vascular Diseases. American Heart Association Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee. Circulation. 2002;106:388-391. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1266] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1253] [Article Influence: 57.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Origasa H, Goto S, Shimada K, Uchiyama S, Okada Y, Sugano K, Hiraishi H, Uemura N, Ikeda Y; MAGIC Investigators. Prospective cohort study of gastrointestinal complications and vascular diseases in patients taking aspirin: rationale and design of the MAGIC Study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2011;25:551-560. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hiraishi H, Oki R, Tsuchida K, Yoshitake N, Tominaga K, Kusano K, Hashimoto T, Maeda M, Sasai T, Shimada T. Frequency of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated ulcers. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2012;5:171-176. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, Liu L, Wang D, Wang C, Wang C, Li H, Meng X, Cui L. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:11-19. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1063] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1070] [Article Influence: 97.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Uemura N, Sugano K, Hiraishi H, Shimada K, Goto S, Uchiyama S, Okada Y, Origasa H, Ikeda Y; MAGIC Study Group. Risk factor profiles, drug usage, and prevalence of aspirin-associated gastroduodenal injuries among high-risk cardiovascular Japanese patients: the results from the MAGIC study. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:814-824. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Taha AS, Angerson WJ, Knill-Jones RP, Blatchford O. Upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage associated with low-dose aspirin and anti-thrombotic drugs - a 6-year analysis and comparison with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:285-289. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Kamada T, Haruma K, Ito M, Inoue K, Manabe N, Matsumoto H, Kusunoki H, Hata J, Yoshihara M, Sumii K. Time Trends in Helicobacter pylori Infection and Atrophic Gastritis Over 40 Years in Japan. Helicobacter. 2015;20:192-198. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 62] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lanas A, Scheiman J. Low-dose aspirin and upper gastrointestinal damage: epidemiology, prevention and treatment. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:163-173. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 126] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shiotani A, Nishi R, Yamanaka Y, Murao T, Matsumoto H, Tarumi K, Kamada T, Sakakibara T, Haruma K. Renin-angiotensin system associated with risk of upper GI mucosal injury induced by low dose aspirin: renin angiotensin system genes’ polymorphism. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:465-471. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Antithrombotic Trialists' (ATT) Collaboration, Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, Emberson J, Godwin J, Peto R, Buring J, Hennekens C, Kearney P, Meade T, Patrono C, Roncaglioni MC, Zanchetti A. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373:1849-1860. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2661] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2442] [Article Influence: 162.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lanza FL, Chan FK, Quigley EM; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for prevention of NSAID-related ulcer complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:728-738. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 363] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 397] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nikolsky E, Stone GW, Kirtane AJ, Dangas GD, Lansky AJ, McLaurin B, Lincoff AM, Feit F, Moses JW, Fahy M. Gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with acute coronary syndromes: incidence, predictors, and clinical implications: analysis from the ACUITY (Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1293-1302. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 142] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hallas J, Dall M, Andries A, Andersen BS, Aalykke C, Hansen JM, Andersen M, Lassen AT. Use of single and combined antithrombotic therapy and risk of serious upper gastrointestinal bleeding: population based case-control study. BMJ. 2006;333:726. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 267] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ibáñez L, Vidal X, Vendrell L, Moretti U, Laporte JR; Spanish-Italian Collaborative Group for the Epidemiology of Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding associated with antiplatelet drugs. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:235-242. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 81] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sakamoto C, Sugano K, Ota S, Sakaki N, Takahashi S, Yoshida Y, Tsukui T, Osawa H, Sakurai Y, Yoshino J. Case-control study on the association of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in Japan. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:765-772. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 82] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | O'Donnell MJ, Kapral MK, Fang J, Saposnik G, Eikelboom JW, Oczkowski W, Silva J, Gould L, D’Uva C, Silver FL; Investigators of the Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network. Gastrointestinal bleeding after acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2008;71:650-655. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 55] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lanas A, García-Rodríguez LA, Arroyo MT, Gomollón F, Feu F, González-Pérez A, Zapata E, Bástida G, Rodrigo L, Santolaria S. Risk of upper gastrointestinal ulcer bleeding associated with selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors, traditional non-aspirin non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin and combinations. Gut. 2006;55:1731-1738. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 358] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 382] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Delaney JA, Opatrny L, Brophy JM, Suissa S. Drug drug interactions between antithrombotic medications and the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. CMAJ. 2007;177:347-351. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 141] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lanas Á, Carrera-Lasfuentes P, Arguedas Y, García S, Bujanda L, Calvet X, Ponce J, Perez-Aísa Á, Castro M, Muñoz M, Sostres C, García-Rodríguez LA. Risk of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding in patients taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelet agents, or anticoagulants. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:906-12.e2. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 170] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Shimomura A, Nagata N, Shimbo T, Sakurai T, Moriyasu S, Okubo H, Watanabe K, Yokoi C, Akiyama J, Uemura N. New predictive model for acute gastrointestinal bleeding in patients taking oral anticoagulants: A cohort study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33:164-171. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Senoo K, Lau YC, Dzeshka M, Lane D, Okumura K, Lip GY. Efficacy and safety of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants vs. warfarin in Japanese patients with atrial fibrillation – meta-analysis. Circ J. 2015;79:339-345. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Miller CS, Dorreen A, Martel M, Huynh T, Barkun AN. Risk of Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Patients Taking Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1674-1683.e3. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 91] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Serebruany VL, Steinhubl SR, Berger PB, Malinin AI, Baggish JS, Bhatt DL, Topol EJ. Analysis of risk of bleeding complications after different doses of aspirin in 192,036 patients enrolled in 31 randomized controlled trials. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:1218-1222. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 236] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | García Rodríguez LA, Lin KJ, Hernández-Díaz S, Johansson S. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with low-dose acetylsalicylic acid alone and in combination with clopidogrel and other medications. Circulation. 2011;123:1108-1115. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 145] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1996;38:316-321. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 888] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 853] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sung JJ, Tsoi KK, Ma TK, Yung MY, Lau JY, Chiu PW. Causes of mortality in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding: a prospective cohort study of 10,428 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:84-89. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 198] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Blatchford O, Davidson LA, Murray WR, Blatchford M, Pell J. Acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in west of Scotland: case ascertainment study. BMJ. 1997;315:510-514. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 212] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Stanley AJ, Laine L, Dalton HR, Ngu JH, Schultz M, Abazi R, Zakko L, Thornton S, Wilkinson K, Khor CJ. Comparison of risk scoring systems for patients presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: international multicentre prospective study. BMJ. 2017;356:i6432. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 187] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Travis AC, Wasan SK, Saltzman JR. Model to predict rebleeding following endoscopic therapy for non-variceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1505-1510. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Witt DM, Delate T, Garcia DA, Clark NP, Hylek EM, Ageno W, Dentali F, Crowther MA. Risk of thromboembolism, recurrent hemorrhage, and death after warfarin therapy interruption for gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1484-1491. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 165] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Maulaz AB, Bezerra DC, Michel P, Bogousslavsky J. Effect of discontinuing aspirin therapy on the risk of brain ischemic stroke. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:1217-1220. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 226] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kim SY, Hyun JJ, Suh SJ, Jung SW, Jung YK, Koo JS, Yim HJ, Park JJ, Chun HJ, Lee SW. Risk of Vascular Thrombotic Events Following Discontinuation of Antithrombotics After Peptic Ulcer Bleeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:e40-e44. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Sung JJ, Lau JY, Ching JY, Wu JC, Lee YT, Chiu PW, Leung VK, Wong VW, Chan FK. Continuation of low-dose aspirin therapy in peptic ulcer bleeding: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:1-9. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 261] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Nagata N, Sakurai T, Shimbo T, Moriyasu S, Okubo H, Watanabe K, Yokoi C, Yanase M, Akiyama J, Uemura N. Acute Severe Gastrointestinal Tract Bleeding Is Associated With an Increased Risk of Thromboembolism and Death. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1882-1889.e1. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Sugano K, Matsumoto Y, Itabashi T, Abe S, Sakaki N, Ashida K, Mizokami Y, Chiba T, Matsui S, Kanto T. Lansoprazole for secondary prevention of gastric or duodenal ulcers associated with long-term low-dose aspirin therapy: results of a prospective, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, double-dummy, active-controlled trial. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:724-735. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Sanuki T, Fujita T, Kutsumi H, Hayakumo T, Yoshida S, Inokuchi H, Murakami M, Matsubara Y, Kuwayama H, Kawai T. Rabeprazole reduces the recurrence risk of peptic ulcers associated with low-dose aspirin in patients with cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease: a prospective randomized active-controlled trial. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1186-1197. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Sugano K, Choi MG, Lin JT, Goto S, Okada Y, Kinoshita Y, Miwa H, Chiang CE, Chiba T, Hori M. Multinational, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, prospective study of esomeprazole in the prevention of recurrent peptic ulcer in low-dose acetylsalicylic acid users: the LAVENDER study. Gut. 2014;63:1061-1068. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Yeomans N, Lanas A, Labenz J, van Zanten SV, van Rensburg C, Rácz I, Tchernev K, Karamanolis D, Roda E, Hawkey C. Efficacy of esomeprazole (20 mg once daily) for reducing the risk of gastroduodenal ulcers associated with continuous use of low-dose aspirin. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2465-2473. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 165] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 42. | Satoh K, Yoshino J, Akamatsu T, Itoh T, Kato M, Kamada T, Takagi A, Chiba T, Nomura S, Mizokami Y. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for peptic ulcer disease 2015. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:177-194. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 83] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |