Published online Jun 14, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i22.4121

Peer-review started: February 2, 2017

First decision: February 23, 2017

Revised: March 6, 2017

Accepted: March 30, 2017

Article in press: March 30, 2017

Published online: June 14, 2017

We present a case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (CCS) in which the entire intestine was observed using a prototype of magnifying single-balloon enteroscope (SIF Y-0007, Olympus). CCS is a rare, non-familial gastrointestinal polyposis with ectodermal abnormalities. To our knowledge, this is the first report showing magnified intestinal lesions of CCS. A 73-year-old female visited our hospital with complaints of diarrhea and dysgeusia. The blood test showed mild anemia and hypoalbuminemia. The esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy revealed diffuse and reddened sessile to semi-pedunculated polyps, resulting in the diagnosis of CCS. In addition to the findings of conventional balloon-assisted enteroscopy or capsule endoscopy, magnifying observation revealed tiny granular structures, non-uniformity of the villus, irregular caliber of the loop-like capillaries, scattered white spots in the villous tip, and patchy redness of the villus. Histologically, the scattered white spots and patchy redness of the villus reflect lymphangiectasia and bleeding to interstitium, respectively.

Core tip: While the endoscopic findings using esophagogastroduodenoscopy or colonoscopy of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (CCS) are common, there have been few reports visualizing the small intestinal lesions of CCS. We have used a prototype of magnifying single-balloon enteroscope and have shown the detailed image of the small intestinal lesions of CCS. We also find some novel findings of CCS, some of which were confirmed by histological analysis. We also present a detailed video of this case.

- Citation: Murata M, Bamba S, Takahashi K, Imaeda H, Nishida A, Inatomi O, Tsujikawa T, Kushima R, Sugimoto M, Andoh A. Application of novel magnified single balloon enteroscopy for a patient with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(22): 4121-4126

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i22/4121.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i22.4121

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (CCS) is characterized by gastrointestinal polyposis accompanied by hair loss, nail abnormalities, chromatosis, dysgeusia, and other ectodermal abnormalities. Pathophysiology of CCS also includes protein-losing enteropathy and malabsorption[1]. While the endoscopic findings using esophagogastroduodenoscopy or colonoscopy of CCS are common, there have been few reports visualizing the small intestinal lesions of CCS. We herein present a case of CCS in which the entire intestine was observed using a prototype of magnifying SBE (SIF Y-0007, Olympus). We believe the findings of the present study are of particular importance as no previous reports have identified small intestinal lesions in CCS using magnifying enteroscopy.

A 73-year-old woman developed diarrhea, dysgeusia and loss of appetite in January 2015. Her past medical history included benign lung tumor at age 60 and type II diabetes at age 67. In March 2015, she presented to our hospital because the diarrhea worsened (7 bowel movements per day). She also experienced body weight loss of 4 kg over 3 mo, pedal edema and epigastric pain. Physical examination revealed painful superficial ulcers on the tongue in addition to chromatosis on the dorsum of the hands and nail abnormalities. Edema was present in both legs, and there were loss of head hair, eyebrows, and eyelashes. The laboratory results indicated anemia (hemoglobin 11.6 g/dL) and hypoalbuminemia (serum albumin 2.5 g/dL). Urine albumin was normal. Scintigraphy indicated diffuse protein leakage throughout the entire small bowel. Alpha-1 antitrypsin clearance was elevated at 134 mL/d (normal, < 20 mL/d), and protein leakage from the gastrointestinal tract was observed.

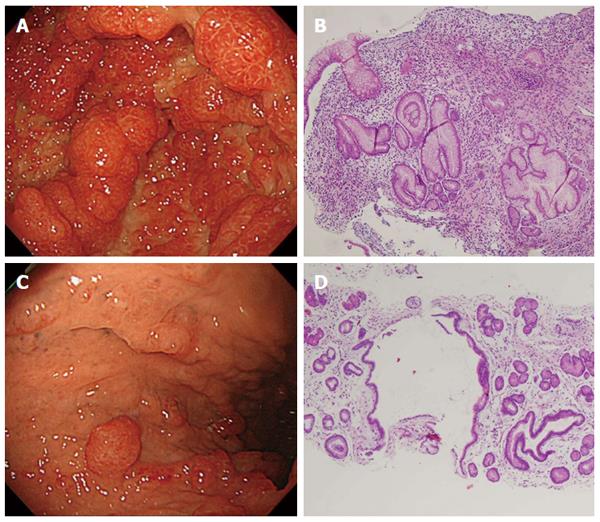

The esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed no abnormal findings in the esophagus. In the stomach, diffuse sessile and semipendunculated polyps were observed predominantly in the antrum. The polyp surfaces were smooth and displayed intense reddening (Figure 1A). On the other hand, in the fundus and upper body of the stomach, there are relatively few polyps (Figure 1C). Biopsies were taken from the polypoid lesion at antrum and the inter-polypoid lesions in the fundus (Figure 1B and D). Histopathological findings of the antral polyp indicated an edematous and myxomatous lesion (Figure 1B). Similar findings were also observed from the biopsy taken from the inter-polypoid mucosa (Figure 1D).

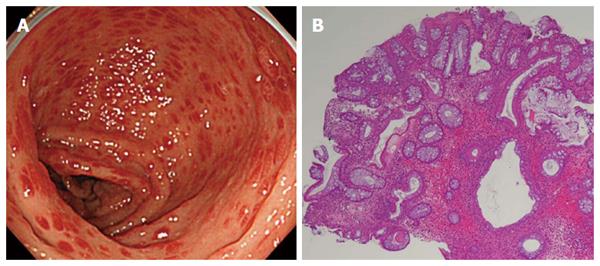

Colonoscopy revealed diffuse sessile and semipundunculated polyps with intense reddening in the entire large bowel (Figure 2A). Histology of the colonic biopsy showed inflammatory cell infiltration, predominantly eosinophilic infiltration, and ductal cystic dilatation (Figure 2B).

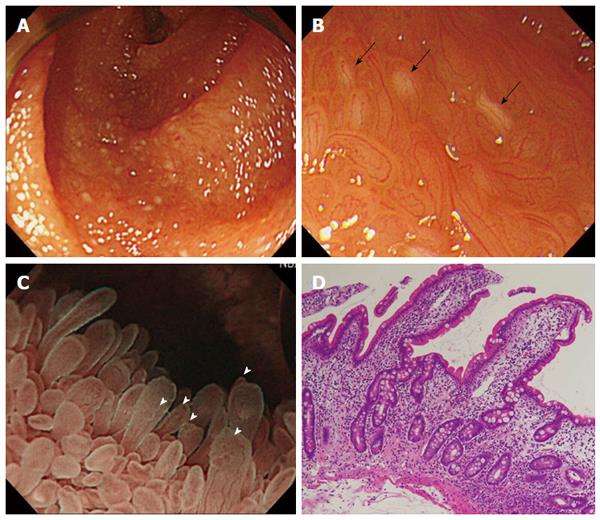

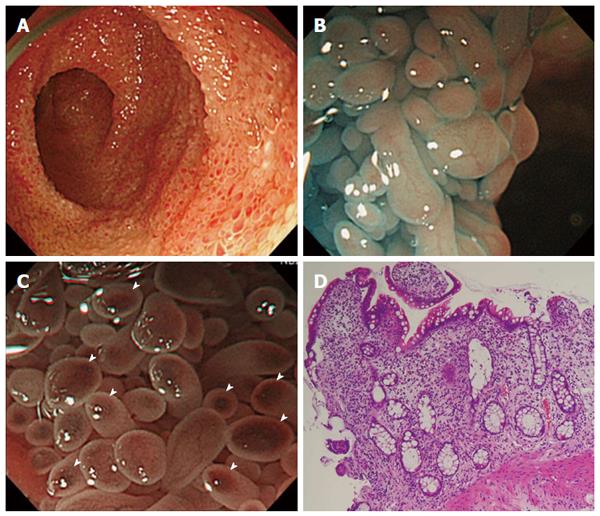

Using a magnifying SBE, we performed an endoscopic examination via both trans-oral and trans-anal routes (Supplemental video). Structural differences in the villi were observed in the jejunum and the ileum. In the jejunum, the villi were predominantly elongated and exhibited scattered white spots (Figure 3A-C). In the ileum, the villi exhibited prominent reddening and swelling with a salmon roe appearance (Figure 4A-C). Magnified observation with narrow-band imaging enabled us to observe villi structure in detail and the presence of loop-like capillaries within villi. Specifically, we were able to clearly observe an irregular villous structure, scattered white spots within the villi, fine granular structures at the tips of villi, irregular caliber of the loop-like capillaries, and spotted villous erythema (Figure 3B, C and Figure 4B, C). Histopathological findings were as follows: jejunal biopsy showed the presence of twisted crypts and interstitial edema (Figure 3D). Ileal biopsy demonstrated elongated crypts and atrophied villus and inflammatory cell infiltration predominantly consisting of eosinophils (Figure 4D). The presence of scattered white spots and spotty erythema was consistent with lymphangiectasia and interstitial bleeding.

Based on the history of the current illness characterized by ectodermal symptoms, the presence of gastrointestinal polyposis, and the results of histopathological assessments, the patient was diagnosed with CCS. Oral administration of prednisolone 30 mg/d and tranexamic acid 1000 mg/d was initiated on day 7 of hospitalization. The patient subsequently reported improvement in symptoms, including a marked reduction in the frequency of diarrhea. The prednisolone dose was gradually reduced, and she was discharged on hospital day 29. However, she was re-admitted to our hospital on day 74 since initial hospitalization, because diarrhea frequency and general malaise worsened. A stool sample taken on the same day indicated the presence of Clostridium difficile (CD) toxin. The patient was diagnosed with worsening due to CD enteritis. On day 79, she was administered metronidazole, resulting in rapid remission of clinical symptoms. She was then discharged on day 113. During subsequent outpatient visits, the prednisolone dose was gradually reduced and eventually discontinued without leading to any recurrence of symptoms. Post-treatment upper and lower GI endoscopic examination and an α1 antitrypsin clearance test were conducted on day 211. Marked improvement in polyposis was noted, particularly in the large bowel, and the presence of adenoma was revealed. No reddening or swelling of the villi in the jejunum and ileum was observed, and the scattered white spots were seen to have disappeared. Gastric biopsy indicated hyperplasia of the ductal epithelium and remnant interstitial swelling; however, the inflammatory cell infiltration had resolved. The result of the α1 antitrypsin clearance test was 9.3 mL/d, indicating marked improvement.

CCS is a relatively rare disease in which ectodermal symptoms are accompanied by gastrointestinal polyposis[1]. CCS tends to occur in middle-aged men and approximately 400 cases have been reported worldwide[2]. As approximately three-quarters of those reports are from Japan, it appears that racial background factors might affect the onset of this disease[3]. Although the pathogenesis of CCS remains unknown, genetic abnormalities[4], abnormal proliferation and differentiation of intestinal epithelium[5], immune-related abnormality[6], and stress[7] have been implicated.

Polyposis in CCS is non-neoplastic, and non-atypical ductal proliferation, cystic dilatation, swelling of the lamina propria mucosa, and marked inflammatory cell infiltration predominantly consisting of eosinophils are observed. Biopsy from the polypoid lesion is not sufficient to differentiate between juvenile polyps and inflammatory polyps[8,9]. Additional biopsies from inter-polypoid lesions also yield the above findings, which are characteristic of CSS and have diagnostic value.

While CCS is thought to cause polyposis throughout the entire gastrointestinal tract except for the esophagus, polyposis in the small bowel is rare. However, some form of small bowel lesion is seen in over half of cases[10,11]. There are few studies reporting the use of endoscopic observation for small bowel lesions. Review of small number of previous reports indicates that typical endoscopic findings in CCS include the following: (1) mucosal edema and enlarged villi[12,13]; (2) reddened mucosa[12,13]; (3) white villus or scattered white spots[12,14]; (4) flat protuberances or small polyps (herpes-like lesions at jejunum[12-15]; and strawberry-like lesions at ileum[12,13,16]; (5) elongated villi[14,16]; and (6) atrophied villi[2,17].

The above findings (1), (2), (3), (5) and (6) were observed in the present case. In addition, villus morphology and the degree of villus reddening and scattered white spots differed between the jejunum and ileum. There have been previous reports of the use of capsule endoscopy to observe changes in the mucosa along the vertical axis of the small bowel[12,13]. New findings using magnified observation include the following: (1) irregular villus structure; (2) scattered white spots within the tips of villi; (3) small granular structure on the tips of villi; (4) irregular caliber of the loop-like capillaries; and (5) spotted reddening within villi. Histological analysis revealed that the scattered white spots reflect the pathological dilatation of the lymphatic ducts. This is consistent with the previous report by Asakura et al[18]. Furthermore, histology revealed that the spotted reddening within the villi reflects interstitial bleeding.

The magnified observation of the small intestine was firstly reported in 1980 by Tada et al[19]. However, the scope (SIF-M, Olympus) needed to be inserted using ropeway method. Therefore, the scope was not widely used. SIF-Y0007 provides a magnification of up to × 80, and has the outer diameter of 9.9 mm which is approximately the same contour as SIF-Q260 with the outer diameter of 9.2 mm. Although an increase in outer diameter of 0.7 mm compared to SIF-Q260, SIF-Y0007 is incorporated passive bending and high force transmission. Therefore, the ability of deep insertion is similar to SIF-Q260 and SIF-Y0007 can be used in a routine examination.

The magnified observation enables us to visualize the detailed morphology of the villus or the loop vessels. Therefore, we are actively using SIF-Y0007 for the patients with protein-losing enteropathy or with known polyps or aggregates of white villi detected by video capsule enteroscopy. Further analysis should be done to investigate the usefulness of magnified endoscopy as a diagnostic tool of intestinal pathogenesis.

There have been few reports of small bowel lesions in cases of CCS. We reported a case in which SBE allowed observation of the entire small bowel affected by CCS.

A 72-year-old woman presented to our hospital because of diarrhea, dysgeusia and loss of appetite.

Physical examination revealed superficial ulcers on the tongue, chromatosis on the dorsum of the hands, nail abnormalities, bilateral leg edema, loss of head hair, eyebrows and eyelashes, indicating ectodermal abnormalities.

Polyposis of the gastrointestinal tract, such as familial adenomatous polyposis, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, juvenile polyposis.

The laboratory results indicated anemia and hypoalbuminemia.

In addition to the diffuse polyposis in the stomach and colon, a magnifying single-balloon enteroscopy enables us to clearly observe an irregular villous structure, scattered white spots within the villi, fine granular structures at the tips of villi, irregular caliber of the loop-like capillaries, and spotted villous erythema in the jejunum and the ileum.

Histopathological findings of the inter-polypoid mucosa at gastric body indicated an edematous and myxomatous lesion, which suggest the diagnosis of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome.

The patient responded to oral prednisolone of 30 mg/d and the dose was gradually tapered.

There have been a few reports of the use of capsule endoscopy or conventional balloon-assisted enteroscopy to observe small intestinal lesion of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome.

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome is characterized by gastrointestinal polyposis accompanied by hair loss, nail abnormalities, chromatosis, dysgeusia, and other ectodermal abnormalities.

Authors have visualized the detailed observation of small intestinal lesion of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome.

The endoscopic pictures and a supplementary video may interact your attention.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chen CH, Imaeda A, Spada C S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Cronkhite LW, Canada WJ. Generalized gastrointestinal polyposis; an unusual syndrome of polyposis, pigmentation, alopecia and onychotrophia. N Engl J Med. 1955;252:1011-1015. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 227] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kopáčová M, Urban O, Cyrany J, Laco J, Bureš J, Rejchrt S, Bártová J, Tachecí I. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: review of the literature. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:856873. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Devulder F, Bouché O, Diebold MD, Abdelli N, Fremond L, Cambier MP, Thiefin G. [Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a new French case]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1999;23:407-408. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Patil V, Patil LS, Jakareddy R, Verma A, Gupta AB. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a report of two familial cases. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2013;32:119-122. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Freeman K, Anthony PP, Miller DS, Warin AP. Cronkhite Canada syndrome: a new hypothesis. Gut. 1985;26:531-536. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Sweetser S, Ahlquist DA, Osborn NK, Sanderson SO, Smyrk TC, Chari ST, Boardman LA. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcomes in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: support for autoimmunity. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:496-502. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 85] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Murata I, Yoshikawa I, Endo M, Tai M, Toyoda C, Abe S, Hirano Y, Otsuki M. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: report of two cases. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:706-711. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Slavik T, Montgomery EA. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome six decades on: the many faces of an enigmatic disease. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67:891-897. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jenkins D, Stephenson PM, Scott BB. The Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: an ultrastructural study of pathogenesis. J Clin Pathol. 1985;38:271-276. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Seshadri D, Karagiorgos N, Hyser MJ. A case of cronkhite-Canada syndrome and a review of gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2012;8:197-201. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Watanabe C, Komoto S, Tomita K, Hokari R, Tanaka M, Hirata I, Hibi T, Kaunitz JD, Miura S. Endoscopic and clinical evaluation of treatment and prognosis of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a Japanese nationwide survey. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:327-336. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yuan B, Jin X, Zhu R, Zhang X, Liu J, Wan H, Lu H, Shen Y, Wang F. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome associated with rib fractures: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:121. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cao XC, Wang BM, Han ZC. Wireless capsule endoscopic finding in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Gut. 2006;55:899-900. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wallenhorst T, Pagenault M, Bouguen G, Siproudhis L, Bretagne JF. Small-bowel video capsule endoscopic findings of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:739-740. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hatogai K, Hosoe N, Imaeda H, Rey JF, Okada S, Ishibashi Y, Kimura K, Yoneno K, Usui S, Ida Y. Role of enhanced visibility in evaluating polyposis syndromes using a newly developed contrast image capsule endoscope. Gut Liver. 2012;6:218-222. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Heinzow HS, Domschke W, Meister T. Innovative video capsule endoscopy for detection of ubiquitously elongated small intestinal villi in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2014;9:121-123. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mönkemüller K, Neumann H, Evert M. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: panendoscopic characterization with esophagogastroduodenoscopy, endoscopic ultrasound, colonoscopy, and double balloon enteroscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:A26. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Asakura H, Miura S, Morishita T, Aiso S, Tanaka T, Kitahora T, Tsuchiya M, Enomoto Y, Watanabe Y. Endoscopic and histopathological study on primary and secondary intestinal lymphangiectasia. Dig Dis Sci. 1981;26:312-320. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Tada M, Suyama Y, Shimizu T, Fujii H, Miyoshi M, Nishimura S, Nishitani T, Katake K, Shimono M, Askasaka Y. Observation of the villi with the magnifying entero-colonoscopes. Gastroenterological Endoscopy. 1980;22:647-654. [Cited in This Article: ] |