Published online Oct 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i40.14965

Revised: March 11, 2014

Accepted: June 13, 2014

Published online: October 28, 2014

AIM: To quantify the association between Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and migraine.

METHODS: A systematic literature search of PubMed and EMBASE was conducted from inception to December 2013. Studies that provided data dealing with H. pylori infection in patients with migraine, as well as healthy controls, were selected. Meta-analysis was carried out using the odds ratio (OR) with a fixed or random effects model, and a 95%CI for the OR was calculated. An unconditional logistic regression model was used to analyze potential parameters related to H. pylori prevalence. Subgroup analyses were conducted as methods of detection and evidence grade.

RESULTS: Five case-control studies published between 2000 and 2013 were finally identified, involving 903 patients, with a total H. pylori infection rate of 39.31%. The prevalence of H. pylori infection was significantly greater in migraineurs than in controls (44.97% vs 33.26%, OR = 1.92, 95%CI: 1.05-3.51, P = 0.001). A sensitivity test indicated that no single study dominated the combined results. Univariate regression analysis found that publication year, geographical distribution and evidence grade were relevant to the results and were the main reason for the heterogeneity. Subgroup analysis found a significantly greater infection rate of H. pylori in Asian patients with migraine, but no statistically significant infection rate in European patients. The ORs were 3.48 (95%CI: 2.09-5.81, P = 0.000) and 1.19 (95%CI: 0.86-1.65, P = 0.288), respectively.

CONCLUSION: The pooled data suggest a trend of more frequent H. pylori infections in patients with migraine.

Core tip: Recently, researchers have focused on the relationship between migraine and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection. Some studies have reported a strong positive correlation, and eradication of the bacterium resulted in a decrease in migraine attacks. Meanwhile, others have indicated totally negative results. In this meta-analysis, we found a trend of more frequent H. pylori infection in patients with migraine; thus, the eradication of this bacterium may reduce the clinical manifestations in migraineurs. Moreover, subgroup analysis found a significantly greater infection rate of H. pylori in patients with migraine in Asia compared with other countries.

-

Citation: Su J, Zhou XY, Zhang GX. Association between

Helicobacter pylori infection and migraine: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(40): 14965-14972 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i40/14965.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i40.14965

Migraine is one of the most common neurological disorders, and is characterized by attacks of severe headache, and autonomic and neurological symptoms. The prevalence of migraine in the general population ranges from 6% to 13%, and is more common in women. The two main types of migraine are migraine with aura, occurring in approximately 25% of patients with migraine, and migraine without aura, occurring in the remaining 75% of patients[1,2]. Migraine without aura seems to be caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors, whereas migraine with aura is probably determined largely by genetic factors[3,4].

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a Gram-negative organism that causes chronic active gastric inflammation. Infection is strongly associated with duodenal ulceration, gastric ulceration and gastric cancer[5]. The association between H. pylori infection and various extraintestinal pathologies, such as coronary heart disease, primary Raynaud’s phenomenon, migraine, Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment, has recently been addressed. However, the results remain controversial[6].

Recently, researchers have focused on the relationship between migraine and H. pylori infection. Some studies have reported a strong positive correlation, and eradication of the bacterium resulted in a decrease of migraine attacks. Meanwhile, others have indicated totally negative results. This meta-analysis was conducted to determine the prevalence of H. pylori infection in patients with migraine and healthy controls, as well as to establish whether H. pylori infection is a risk factor for migraine.

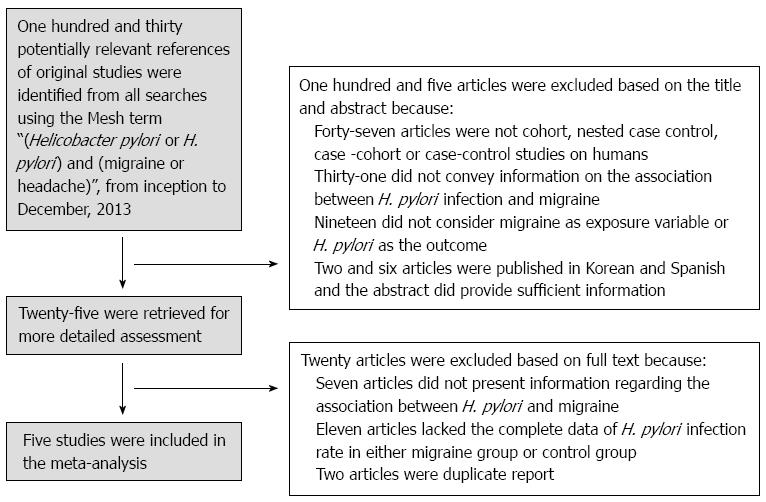

The PRISMA guidelines[7] for conducting meta-analysis were followed. Two investigators (Su J and Zhou XY) performed a systematic literature search of PubMed and Embase, from inception to December 2013, using the medical subject heading terms “(Helicobacter pylori or H. pylori) AND (migraine or headache)”. The two investigators worked independently, at different times and at different medical science information centers affiliated with Nanjing Medical University. The search was repeated several times. The last search was conducted on December 20, 2013. The relevant articles, texts, and reference lists were manually searched to broaden the scope of our findings. We evaluated the full texts of papers published in English, as well as the English abstracts of papers published in other languages.

The inclusion criteria as follows: (1) study design: published case-control and cross-sectional studies; (2) studies that provided data dealing with H. pylori infection in patients with migraine as well as healthy controls; and (3) studies in which H. pylori infection was confirmed by the 13C-urea breath test, mucosal biopsy, enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA), and/or polymerase chain reaction (PCR). At least one positive test was regarded as confirmation of infection.

The exclusion criteria as follows: (1) case reports and observational studies without control groups; (2) studies in which the H. pylori infection rate data were not available for either the study group or the control group; (3) subset of a published article by the same authors; and (4) studies in which research subjects had a history of drug use, including antibiotics, H2 blockers, or proton pump inhibitors, within 4 wk.

The two investigators who performed the literature search also performed the data extraction, working independently. The first authors, year and country of publication, study type, method of detection, and type of specimen identified were recorded for each included study. The numbers of H. pylori-positive and -negative patients in the groups with migraine were collected. When data from one study was reported in more than one manuscript, only one was selected for the meta-analysis, according to the following criteria (applied consecutively): (1) availability of adjusted odds ratio (OR) estimates for patients and controls; (2) longer follow-up period (applicable to nested case-control and cross-sectional analyses); and (3) larger sample size. When the relationship between H. pylori infection and migraine was reported in different articles referring to the same study, both were considered eligible, but only one was included in the meta-analysis. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale scoring system assessed the quality of the studies, which is used to assess nonrandomized trials[8].

In this study, the random effects model or fixed effects model was used for the meta-analysis, according to the heterogeneity between studies. The Q-test (P < 0.10 was considered indicative of statistically significant heterogeneity) and the I² statistic (values of 25%, 50%, and 75% were considered to represent low, medium, and high heterogeneity, respectively) were used to test heterogeneity. The fixed effects model was used when there was no significant heterogeneity (I² < 50%); otherwise, the random effects model was used. I² tests were used to calculate P-values. All the reported P-values were two-sided, and P-values less than 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant for all included studies[9].

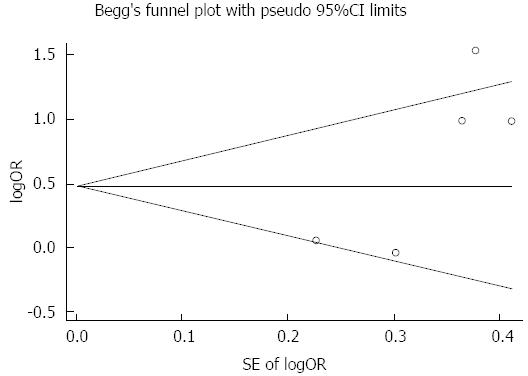

Calculation of dichotomous variables was carried out using the OR with the 95%CI as the summary statistic. The sensitivity test and meta-regression analysis (random effects model) with the restricted maximum likelihood method were used to examine the impact of variables on heterogeneity between studies. Begg’s test was used to evaluate the publication bias[10-11]. Analyses were performed using STATA statistical software, Version 12.0.

The two investigators agreed on the data extraction results. The strategy used for the study selection is displayed in Figure 1. Five studies published between 2000 and 2011 were eligible for the meta-analysis (Table 1). These studies involved 903 patients, with a total H. pylori infection rate of 39.31% (355/903). The cumulative sample size of the study group was 469, of which 210 were H. pylori-positive (44.97%). Of the total 436 controls, 145 (33.26%) were H. pylori-positive. Concerning the H. pylori detection methods, one study used ELISA (serum), two studies used the 13C urea breath test, one study used a biopsy, and one study used both ELISA and the 13C urea breath test.

| Ref. | Year | Country | Method of detection | Specimen | Grade of reference | H. pylori (+) in migraineurs | H. pylori (+) in controls |

| Gasbarrini et al[1] | 2000 | Italy | 13C-UBT | Breath | High | 70/175 | 59/152 |

| Pinessi et al[5] | 2000 | Italy | 13C-UBT, | Breath | High | 31/103 | 32/103 |

| ELISA | Serum | ||||||

| Tunca et al[20] | 2004 | Turkey | Biopsy | Tissue | High | 40/70 | 20/60 |

| Yiannopoulou et al[6] | 2007 | Greece | 13C-UBT | Breath | Low | 30/49 | 19/51 |

| Hosseinzadeh et al[29] | 2011 | Iran | ELISA | Serum | Low | 39/70 | 15/70 |

All of the five included studies reported being approved by the Ethics Committees of their respective institutes and stated that informed consent was obtained from all study participants before enrollment.

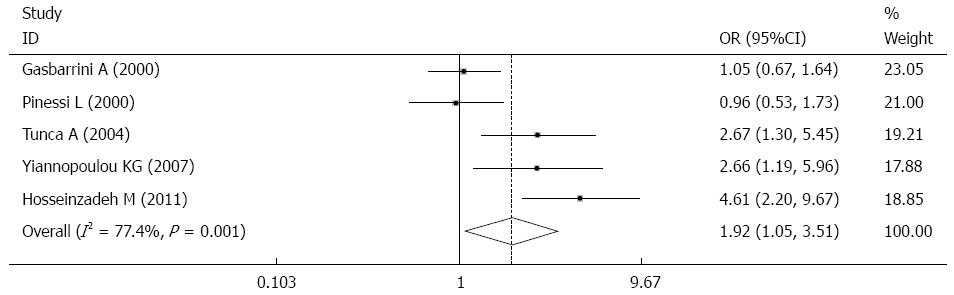

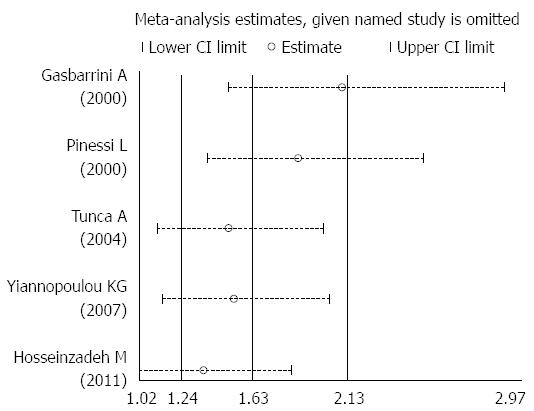

Overall, the prevalence of H. pylori infection was significantly greater in patients with migraine than in controls (44.97% vs 33.26%, OR = 1.92, 95%CI: 1.05-3.51, P = 0.001, I2 = 77.4%) (Figure 2). A sensitivity test indicated that no single study dominated the combined results (Figure 3). Univariate regression analysis and subgroup analysis were performed to investigate the influencing factors that may have impacted the overall results.

The meta-analysis results showed that the prevalence of H. pylori infection in patients with migraine was greater than that in controls, and the heterogeneity was high (I² = 77.4%). Univariate regression analysis found that publication year, geographical distribution, and evidence grade were relevant (P = 0.028, P = 0.041, and P = 0.047, respectively). Subgroup analysis was performed to further investigate the above influencing factors, which may have impacted the overall results.

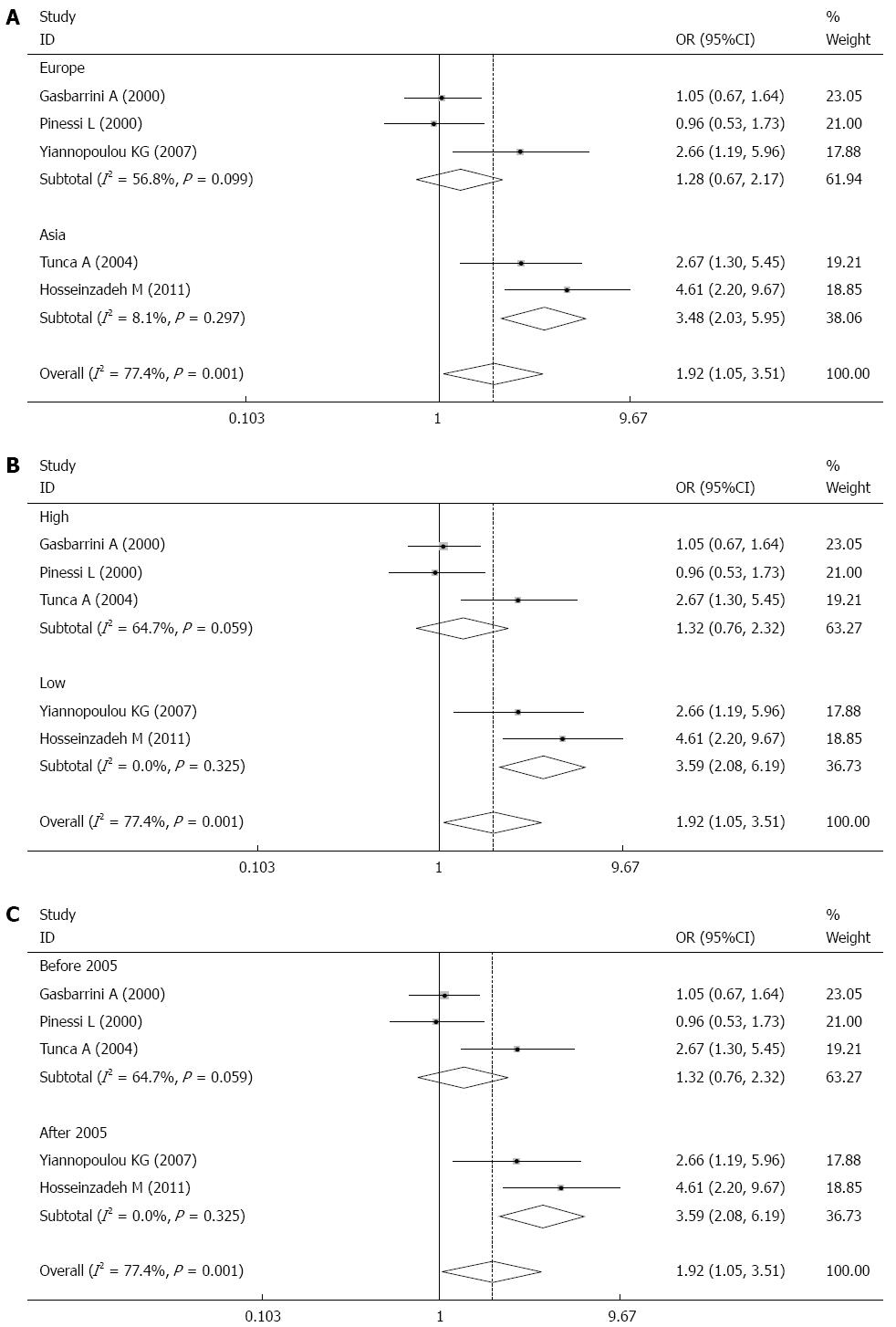

Stratification analysis by geographical region indicated that the levels of H. pylori infection among migraineurs were greater in Asia, but not statistically significant in Europe. The ORs were 3.48 (95%CI: 2.03-5.95) for the two studies conducted in Asia (P = 0.000), and 1.28 (95%CI: 0.76-2.17) for the three studies from Europe (P = 0.358) (Figure 4A).

Subgroup analysis assessing the quality of evidence for each included study was performed, and each study was classified into low, moderate, or high quality. Two studies were included in the low quality group, and the pooled data indicated that the positive rate of H. pylori infection was greater in the migraine group than in the control group (OR = 3.60, 95%CI: 2.09-6.19, P = 0.000). Three studies were included in the high quality group, and the positive rate of infection was similar between the migraine and control groups (OR = 1.23, 95%CI: 0.90-1.69, P = 0.190) (Figure 4B).

Three studies published between 2000 and 2005 were included in our analysis. In these studies, the positive rate of infection was similar between the migraine and control groups (OR = 1.23, 95%CI: 0.90-1.69, P = 0.190). In studies published after 2005, the pooled data indicated that the positive rate of H. pylori infection was greater in the migraine group than in the control group (OR = 3.60, 95%CI: 2.09-6.19, P = 0.000) (Figure 4C).

Funnel plot analysis did not show any evidence of publication bias (Begg’s test; Z = 1.47, P = 0.083, continuity corrected) (Figure 5).

Our meta-analysis, which evaluated a total of five case-control studies, showed that H. pylori infection is indeed a risk factor for migraine. For articles published in recent years, however, the relationship between H. pylori infection and migraine remains controversial. There were probably three reasons why H. pylori infection was not found to be a risk factor for migraine in some studies. First, H. pylori infection can reduce food sensitivity. Food sensitivity is a well-known, but still unexplained, phenomenon for those with migraine[12-14]. Second, migraine is related with vasoactive substances (NO, serotonin, etc.)[15]. Researchers have found that there was no significant difference in plasma thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances and NO metabolites between patients with migraine infected with H. pylori and control subjects[16,17]. Third, the migraineurs who are included in most studies do not have a high incidence of H. pylori infection, since this bacterial infection appears to be age-related[18]. Therefore, the prevalence of H. pylori infection in patients with migraine may be less than or equal to that of healthy people.

However, many studies agree that H. pylori infection is associated with migraine. In our meta-analysis, five studies recruited patients who mainly suffered from migraine without aura because this subtype of migraine seems to be caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors, whereas migraine with aura is probably determined largely, or exclusively, by genetic factors[3-4].

The meta-analysis of five studies from across the globe indicated that H. pylori infection was greater in patients with migraine than in controls (P = 0.000). Recently, it has been suggested that the probable pathogenic role of H. pylori chronic infection in migraine is based on the relationship between the host immune response against the bacterium and the chronic release of vasoactive substances[19]. The host inflammatory response to H. pylori is characterized by infiltration of neutrophils, monocytes and lymphocytes into the gastric mucosa. Recruitment and activation of immune cells in the underlying mucosa involves bacterium chemotaxins, epithelial derived chemotactic peptides (chemokines) such as IL-8 and GRO-α, and proinflammatory cytokines released by mononuclear phagocytes (e.g., tumor necrosis factor-alpha, IL-1 and IL-8) as part of nonspecific immunity[20-22]. The multiplicity and large quantity of vasoactive substances produced may induce a hyperreactivity of cerebral vessels to various well-known trigger factors, such as psychological or physical stress, peculiar foods, female hormones, and others, which are capable of determining the clinical manifestation of the disease[23-26].

Other studies have provided evidence that migraine has a gastrointestinal origin and is related to H. pylori infection to a certain extent. Salmon found that children with recurrent abdominal pain had a high risk of developing migraine and that recurrent abdominal pain was an early expression of migraine in children[27]. Moreover, Mavromichalis et al[28] conducted a study showing that 29 of the 31 patients with migraine had an associated gastrointestinal disorder. H. pylori colonization was found in seven of the children. These findings suggested that upper gastrointestinal mucosal inflammation may play an important role in the pathogenesis not only of recurrent abdominal pain, but also of migraine. Other researchers have found a correlation between migraine and digestive disorders in adults. They found that approximately 75.7% of patients who had migraines also suffered from digestive disorders [reflux (47.1%), gastric ulcers (17.1%), and gastritis (4.3%)], and the prevalence of H. pylori infection was 38.6%[29]. The explanation of this phenomenon is that gastrointestinal neuroendocrine cells can synthesize and secrete 5-hydroxytryptamine, substance P, and vasoactive intestinal polypeptides. When H. pylori infects a cell, inflammation stimulates the cell to secrete these substances and causes a central nervous system disorder by the brain-gut axis, which indirectly proves why most patients have migraine attacks that are associated with gastrointestinal symptoms[30].

There are other reasons for why the prevalence of H. pylori infection is greater in migraineurs than in controls. H. pylori spreads through the fecal-oral route[31] and 60% of patients with migraine have a family history[3]; therefore, bacterial transmission among relatives is an important factor. Except for the above reasons, some individual factors, such as human leukocyte antigen type or other unknown factors, may make an individual more susceptible to the supposed vasospastic triggers induced by H. pylori[32,33].

Recently, certain studies suggested that H. pylori eradication treatment may provide pain relief. Gasbarrini et al[1] studied 225 patients and H. pylori was detected in 40% of the patients by the 13C-urea breath test. With eradication of the bacterium, it was demonstrated that during follow-up for 6 mo, the frequency, density and duration of migraine attacks reduced significantly. Faraji et al[34] conducted a similar randomized, double blind, controlled trial of 64 migraineurs and suggested that H. pylori treatment was significant in the management of migraine headaches among Iranian patients.

For results showing significant heterogeneity (I2 > 50%), we used the random effects model for the meta-analysis. Meanwhile, the influence analysis indicated that no single study dominated the combined results. The high heterogeneity may be derived from the differences of areas, detection methods and study quality. Based on our subgroup results, the reported prevalence of H. pylori infection ranges widely between nations. In developing countries, such as Asia, the infection rate is significantly greater than that in developed countries. The lower prevalence of H. pylori infection in industrialized nations is attributed to the higher standards of hygiene and socioeconomics. Meanwhile, it has been suggested that ethnicity and place of birth may also play a role in susceptibility to H. pylori infection[35]. Furthermore, our subgroup analysis found that the levels of H. pylori infection among patients with migraine were greater in Asia, but not statistically different in Europe. This fact might result from a significantly greater prevalence of H. pylori cagA-positive strains in Asian countries[36]. It has been shown that cagA-positive strains cause greater release of cytokines by gastric epithelial cells[37]. The high persistent inflammatory response to cagA-positive strains of the bacterium induces a hyperreactivity of cerebral vessels to various well-known trigger factors, such as psychological or physical stress, peculiar foods, female hormones and others that are related to migraine[1]. The H. pylori infection rate reported in cases was slightly greater in the years after 2005 than in the 2000-2005 period. This difference is mainly explained by the fact that the enrolled articles from 2000-2005 are mostly from developed countries, where the H. pylori infection rate is decreasing[38,39].

After the completion of our study, a recent review paper also indicated that the eradication of H. pylori seems to be efficient in patients suffering from migraine[40]. In conclusion, our updated and cumulative meta-analysis of five studies suggests a trend of more frequent H. pylori infection in patients with migraine. Patients with migraine should have their H. pylori infection treated, since bacterial eradication has been shown to reduce the clinical manifestations of migraine. Considering the obvious heterogeneity, more studies including larger sample sizes should be done in the future to further clarify the association between H. pylori infection and migraine.

First, the selection of the controls varied between studies. Second, the H. pylori infection was diagnosed by different methods and strategies among the studies, with some relying on a single detection method, while others used more than one method. These variations may have produced different positive rates of H. pylori infection because of advances in each of the technologies, thus influencing the cumulative positive rates. Third, the papers included in the present meta-analysis were limited to those published and listed on PubMed up to December 2013; therefore, it is possible that some relevant published studies, which may have met the inclusion criteria, were missed. These overlooked studies may have corrected some inherent biases caused by the study design. Finally, the fact that the data were derived from the abstracts of papers not written in English might contribute to the selection bias.

We would like to thank Prof. Rong-Bin Yu for his kind help in reviewing our statistical process and advising on the study design.

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a Gram-negative organism, and its infection is associated with some extraintestinal pathologies, such as coronary heart disease, primary Raynaud’s phenomenon and migraine. However, the relationship between infection and the above diseases remains controversial.

Many researchers have focused on the relationship between migraine and H. pylori infection. Some studies have reported a strong positive correlation, but others have indicated totally negative results. This meta-analysis was performed to quantify the association between H. pylori infection and migraine.

This meta-analysis was conducted to determine the prevalence of H. pylori infection in patients with migraine and healthy controls, and to demonstrate whether H. pylori infection is a risk factor for migraine. Meanwhile, factors including publication year, geographical distribution and evidence grade were also analyzed. From our data, authors found a trend of more frequent H. pylori infection in patients with migraine.

The results suggested that people with migraine may have a higher prevalence of H. pylori infection than healthy people. For migraineurs infected with H. pylori, the eradication of this bacterium may reduce their clinical manifestations.

Migraine is a primary episodic headache disorder characterized by various combinations of neurological, gastrointestinal, and autonomic changes. Migraineurs are people who are diagnosed with migraine.

This is an interesting and timely study, which tackles an important clinical issue. The authors conducted this meta-analysis to determine the prevalence of H. pylori infection in patients with migraine and healthy controls, as well as to demonstrate whether H. pylori infection is a risk factor for migraine. The results are interesting and suggest that a trend of increased prevalence of H. pylori infection was found in patients with migraine. However, more studies including larger samples sizes should be done in the future to further clarify the association between H. pylori infection and migraine.

P- Reviewer: Dore MP, Shimatani T, Tarnawski AS, Wang W, Youn HS S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Stewart G

E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Gasbarrini A, Gabrielli M, Fiore G, Candelli M, Bartolozzi F, De Luca A, Cremonini F, Franceschi F, Di Campli C, Armuzzi A. Association between Helicobacter pylori cytotoxic type I CagA-positive strains and migraine with aura. Cephalalgia. 2000;20:561-565. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, Diamond ML, Reed M. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001;41:646-657. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1534] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1497] [Article Influence: 65.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Piane M, Lulli P, Farinelli I, Simeoni S, De Filippis S, Patacchioli FR, Martelletti P. Genetics of migraine and pharmacogenomics: some considerations. J Headache Pain. 2007;8:334-339. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Russell MB, Olesen J. Increased familial risk and evidence of genetic factor in migraine. BMJ. 1995;311:541-544. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 249] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pinessi L, Savi L, Pellicano R, Rainero I, Valfrè W, Gentile S, Cossotto D, Rizzetto M, Ponzetto A. Chronic Helicobacter pylori infection and migraine: a case-control study. Headache. 2000;40:836-839. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yiannopoulou KG, Efthymiou A, Karydakis K, Arhimandritis A, Bovaretos N, Tzivras M. Helicobacter pylori infection as an environmental risk factor for migraine without aura. J Headache Pain. 2007;8:329-333. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Swartz MK. The PRISMA statement: a guideline for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Pediatr Health Care. 2011;25:1-2. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 129] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603-605. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8858] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10617] [Article Influence: 758.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177-188. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26739] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28498] [Article Influence: 749.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Arena VC. A program to compute the generalized Mantel-Haenszel chi-square for multiple 2 x J tables. Comput Programs Biomed. 1983;17:65-72. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629-634. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34245] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36038] [Article Influence: 1334.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Moffett AM, Swash M, Scott DF. Effect of chocolate in migraine: a double-blind study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1974;37:445-448. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Finocchi C, Sivori G. Food as trigger and aggravating factor of migraine. Neurol Sci. 2012;33 Suppl 1:S77-S80. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 64] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Matysiak-Budnik T, Terpend K, Alain S, Sanson le Pors MJ, Desjeux JF, Mégraud F, Heyman M. Helicobacter pylori alters exogenous antigen absorption and processing in a digestive tract epithelial cell line model. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5785-5791. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Rathnasiri Bandara SM. Paranasal sinus nitric oxide and migraine: a new hypothesis on the sino rhinogenic theory. Med Hypotheses. 2013;80:329-340. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ciancarelli I, Di Massimo C, Tozzi-Ciancarelli MG, De Matteis G, Marini C, Carolei A. Helicobacter pylori infection and migraine. Cephalalgia. 2002;22:222-225. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Tunca A, Ardiçoğlu Y, Kargili A, Adam B. Migraine, Helicobacter pylori, and oxidative stress. Helicobacter. 2007;12:59-62. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Farri A, Enrico A, Farri F. Headaches of otolaryngological interest: current status while awaiting revision of classification. Practical considerations and expectations. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2012;32:77-86. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Asghar MS, Hansen AE, Amin FM, van der Geest RJ, Koning Pv, Larsson HB, Olesen J, Ashina M. Evidence for a vascular factor in migraine. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:635-645. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 220] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tunca A, Türkay C, Tekin O, Kargili A, Erbayrak M. Is Helicobacter pylori infection a risk factor for migraine? A case-control study. Acta Neurol Belg. 2004;104:161-164. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Shimada T, Terano A. Chemokine expression in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric mucosa. J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:613-617. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bodger K, Crabtree JE. Helicobacter pylori and gastric inflammation. Br Med Bull. 1998;54:139-150. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Cutrer FM, Sorensen AG, Weisskoff RM, Ostergaard L, Sanchez del Rio M, Lee EJ, Rosen BR, Moskowitz MA. Perfusion-weighted imaging defects during spontaneous migrainous aura. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:25-31. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 254] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Friberg L, Olesen J, Lassen NA, Olsen TS, Karle A. Cerebral oxygen extraction, oxygen consumption, and regional cerebral blood flow during the aura phase of migraine. Stroke. 1994;25:974-979. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 61] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lauritzen M. Pathophysiology of the migraine aura. The spreading depression theory. Brain. 1994;117:199-210. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 826] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 776] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Woods RP, Iacoboni M, Mazziotta JC. Brief report: bilateral spreading cerebral hypoperfusion during spontaneous migraine headache. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1689-1692. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 458] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 471] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Salmon MA. Migraine in childhood. Nurs Mirror. 1977;145:16-17. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Mavromichalis I, Zaramboukas T, Giala MM. Migraine of gastrointestinal origin. Eur J Pediatr. 1995;154:406-410. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Hosseinzadeh M, Khosravi A, Saki K, Ranjbar R. Evaluation of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with common migraine headache. Arch Med Sci. 2011;7:844-849. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Mavromichalis I. The role of Helicobacter pylori infection in migraine. Cephalalgia. 2003;23:240; author reply 240-241. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Homan M, Hojsak I, Kolaček S. Helicobacter pylori in pediatrics. Helicobacter. 2012;17 Suppl 1:43-48. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Fujiwara Y, Yamanaka O, Nakamura T, Yamaguchi H. Coronary spasm in two sisters. Jpn Circ J. 1993;57:472-474. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Negrini R, Savio A, Poiesi C, Appelmelk BJ, Buffoli F, Paterlini A, Cesari P, Graffeo M, Vaira D, Franzin G. Antigenic mimicry between Helicobacter pylori and gastric mucosa in the pathogenesis of body atrophic gastritis. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:655-665. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 235] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Faraji F, Zarinfar N, Zanjani AT, Morteza A. The effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on migraine: a randomized, double blind, controlled trial. Pain Physician. 2012;15:495-498. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Epplein M, Cohen SS, Sonderman JS, Zheng W, Williams SM, Blot WJ, Signorello LB. Neighborhood socio-economic characteristics, African ancestry, and Helicobacter pylori sero-prevalence. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:897-906. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Vaziri F, Najar Peerayeh S, Alebouyeh M, Mirzaei T, Yamaoka Y, Molaei M, Maghsoudi N, Zali MR. Diversity of Helicobacter pylori genotypes in Iranian patients with different gastroduodenal disorders. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5685-5692. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Ogura K, Maeda S, Nakao M, Watanabe T, Tada M, Kyutoku T, Yoshida H, Shiratori Y, Omata M. Virulence factors of Helicobacter pylori responsible for gastric diseases in Mongolian gerbil. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1601-1610. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 224] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Hanafi MI, Mohamed AM. Helicobacter pylori infection: seroprevalence and predictors among healthy individuals in Al Madinah, Saudi Arabia. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2013;88:40-45. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Naja F, Kreiger N, Sullivan T. Helicobacter pylori infection in Ontario: prevalence and risk factors. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:501-506. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 40. | Savi L, Ribaldone DG, Fagoonee S, Pellicano R. Is Helicobacter pylori the infectious trigger for headache?: A review. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2013;13:313-317. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |